chapter five

Where Story is going

The empowerment of individuals, pre-eminently through social media and networking, is potentially eroding distinctions – between internal and external, audience and author, brand owner and brand consumer – that have traditionally defined communications practice. How these developments affect storytelling and the principles I’ve so earnestly elaborated, I will now consider in this, the denouement of my story. This involves revisiting my model for the storytelling landscape I introduced in the first section, to consider what impact emergent trends might have on the future of corporate storytelling.

The landscape of storytelling revisited

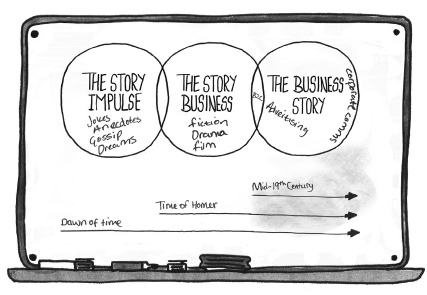

I envisaged the landscape of storytelling involving three interlocking spheres arranged as a spectrum. At one extreme is what I have called the Story Impulse. This contains the everyday world of storytelling most humans participate in naturally, even unconsciously, every single day. This is storytelling at its most basic and informal, with roots deep into the origins of our species. Gossip is the most representative form of storytelling belonging to this sphere.

The second sphere, which I’ve entitled the Story Business, is far more structured and professional. It employs story as a conscious practice, applying the craft of narrative to exploit for pleasure and profit the same impulses found in the first sphere. Whilst we know its stories are not true, we still welcome and actively seek them out. Any form of fiction, be it literary, cinematic, or dramatic, characterises storytelling in this sphere.

The third sphere I’ve called the Business Story. This contains all the arts of communication in the service of commerce or administration. Despite its high professionalism it is only semi-structured in its storytelling, low on credibility and acceptance. Ironically, despite its claims to veracity, people are less ready to believe the stories issuing from this sphere than the fictions coming from the second, which appeal to the truth of human nature. Jargon is its characteristic form, which signals its self-imposed isolation from the first sphere. Paradoxically, these are the people it ultimately depends on, to sell its stuff or services to. Sphere number three desperately needs sphere number one to trust it more.

I suggested that the way for this third sphere to gain the trust of the first was to consciously adopt some of the principles of the second. By actively embracing storytelling it might just get a little closer to the world it needs to reach. The main message of this book is that the Business Story needs to embrace the Story Business if it is to achieve its objectives.

But that’s a snapshot of a stable landscape, which has persisted until relatively recently. Emerging developments mean this picture has to be revised and a new hypothesis proposed.

The three spheres can be understood historically as well as spatially. They correspond to three roughly sequential epochs, each with its own timeline. The timeline for the first sphere is the longest, stretching from prehistory up to the present day and beyond. The same impulse to tell, consume and share stories characterises this vast expanse of history. And whilst different technological and socio-economic developments have changed the way this fundamental impulse has been indulged in or exploited, the basic cognitive equipment within humans has remained exactly the same. Humankind is the universal variable in this timeline, which runs unbroken through all the developments associated with the other two spheres.

The second sphere is the second oldest, and its timeline starts some time at the origins of recorded history and literacy, where the oral traditions of narrative started to gain recognisable and reproducible shape. Archetypes and mythological figures that had circulated in oral forms, and associated with religious beliefs became literary figures whose adventures gave pleasure for their own sake. With Homer the figure of the poet as (semi) professional storyteller was born. Formal rules, such as those stipulated in Aristotle’s Poetics, and subsequent arts of ‘Poesie’, ensured that storytelling was elevated into a craft dominated by a literate, leisured elite.

The two main strands that characterise this timeline are singleness of authority and the increasing distribution of content through successive technological developments. Whilst oral storytelling belonged to everyone, professional storytelling established the author as a single source of meaning and value. The most famous example of the multiple becoming singular is the editing and translation of the Bible into a closed and approved authority (the exact antithesis of the Wiki ethos).

With print the fluid became fixed and ownable. Poets, dramatists, novelists, and then film-makers put their stamp on ideas, by deftly wielding the formal tools of the craft. Post-Enlightenment, the poetic became the professional, and in time authors claimed intellectual property in their stories. Copyright became internationally established in the nineteenth century to allow authors to own and restrict the commercial reproduction of their stories that could now be circulated by print technology on a mass scale. From the printing press to the television, and then the Internet, technology has enabled authors to disseminate their stories to larger and larger audiences, as a way of exploiting the intellectual property residing in their words on a page or images on a screen. Authors ultimately became brands in this epoch.

Storytelling comes full circle

But the Internet and social networking have started to shift the balance of power, and bring about something of a revolution in storytelling. A revolution because, by challenging the ‘Broadcast’ mode of single source authorship and controlled technological dissemination, storytelling is re-acquiring many of its earliest attributes. By forging ahead through technology, it is actually returning to its origins in some of the following ways:

From authorial owners to multiple sharers. Before writing and the rise of the professional author as the single source of content, stories belonged to everybody. They would circulate freely in different forms, evolving with each retelling into something new. In the oral tradition stories remained permanently work-in-progress and collectivist. Something of this ethos is returning with the distributive publishing of content across social networks.

Jonah Sachs has recently pointed to the paradox that digital technology is actually encouraging a return to oral traditions of pre-professional narrative participation. He uses the term ‘Digitoral’ to characterise this ironic quirk of history. For him Digitoral marks the demise of the Broadcast epoch dominated by the professional practices of the Story Business. As he explains, in the Broadcast tradition information is generated, fixed and disseminated by an elite, and so it’s “very difficult, and usually illegal, to change it. Audiences don’t interpret it, mash it up, and retell it… They consume it”. In the Digitoral era, however, “ideas are never fixed: they’re owned and modified by everyone. They move through networks at the will of their members and without that activity, they die”. Distribution technologies have initiated a return to oral traditions, enabling the many to participate in and transform what was once controlled by the few.

YouTube perhaps provides the most mainstream manifestation of this ethos at work for pop culture, but it has made significant inroads into the very heartland of professional storytelling in the shape of Fan Fiction. The most powerful stories have always taken on lives of their own, growing in the imaginations of their audiences to achieve mythic existence beyond the confines of the page. Sites like Fanfiction.net allow the possibilities envisaged in the original cannon of writers such as J.K. Rowling, Stephanie Meyers, and even Conan Doyle or Dickens, to be explored through fictional elaboration by a community of creative devotees.

As the earliest fictions were myths and legends, with multiple variants about the exploits of mythical beings, so the most popular genres for technologically-enabled transformation reside in the fantasy end of the fictional spectrum. The most popular book-based canons to be given this fan-fuelled afterlife on Fanfiction.net are Harry Potter, Twilight, and Lord of the Rings. The mythic is as relevant and as resonant today as it was for pre-professional narrative communities. The impassioned involvement of industrious amateurs restores the positive meaning of that temporarily degraded term, as one laborious for the genuine love of it.

From passive, private consumption to real-time active participation. Stories were originally publically performed rather than privately consumed. Drama derived from religious rituals, and something of public performance of narrative survived even into the nineteenth-century. Before the rise of mass literacy and cheap paper, stories would be read aloud to large groups of individuals. The reading of stories at school, or by parents preserves some of this ritualistic magic. Children love (although parents hate) hearing the same story over and over again. Partly because they learn by repetition, and take pleasure in recognition of the familiar in the formative stages of cognitive development, but also because of the incantatory ritualistic nature of storytelling. Story is not entirely about content, part of its pleasure resides in the act of sharing the experience with others.

Whilst passive consumption of stories has characterised, at least the literary arts, since the Renaissance, something of the experiential aspect of communication has returned. The multiple connectedness of isolated individuals through technology, paradoxically brings them closer than they have been for decades. The real-time exchange of anecdotes, stories, and pre-eminently video as the viral medium of choice, around the globe makes narrative participatory again. Video is far more social than text, and its contagiousness as a medium underlines the appetite for the social aspects of narrative exchange social media has restored.

Gossip goes global. At the very least, the human need to communicate has gained unprecedented amplification and potential influence by the technologies at its disposal. I suggested that gossip is perhaps the most representative narrative mode of the Story Impulse. And it is gossip, in various shapes that keeps the Twitter feeds and word-of-mouth global grapevines so voluminously buzzing. As Peter Morville observes:

“Of course, we’ve co-opted the technology infrastructure, extended the locus of gossip from the water cooler to cyberspace… at the heart of many of today’s killer applications lies the power and prevalence of gossip. It may not be ideal with respect to ethics or efficiency, but it’s the way people are wired, and the blueprint is ancient and immutable”.

In various ways the “ancient and immutable” impulses of story gain mastery of the media of its mass circulation. The oral, the collectivist and the anecdotal restore storytelling to its pre-professional origins. That is not to say that the identifiable forms and structures of the Story Business have been completely abandoned in this new world of empowered amateurs. These principles were formalised because they rested upon the psychological needs narrative has always served. From the very start, social media expressed an ingrained narrative bias and conformed to storytelling conventions.

The first popular incarnations of what is now called social media were memorial. Sites like classmates.com (1995-) and friendsreunited (2000-) in the UK allowed the ‘back stories’ of millions of lives to be revisited and resumed. These reconnections no doubt reignited countless old flames, and so ‘up-dating’ became literally that: updating ‘what might have been’ into ‘happy ever after’. Romance and nostalgia turned a geeky coterie into a mainstream phenomenon, driven by the urge to connect through reminiscence. Friendsreunited has even spawned an offshoot called ‘genesreunited’ to allow the back stories of millions to take on generational dimensions. Preserving genealogy was one of the earliest functions of oral poetry, as all those tedious lists of ancestors in Norse sagas testify. Blogs revived the epistolary and diary forms of some of the earliest novels, where authors then and now wanted to bring dramatic immediacy and authentic intimacy to first-person accounts of the world in which they lived. Blogs live or die by the quality of their content and its ability to engage, adapting the rules of storytelling practice to the demands of concision in a highly competitive context.

And whilst social media is a living, performative form of expansive connectivity, it is leaving permanent traces that one day will render up meaningful narrative. Curatorial sites such as Pinterest constitute cabinets of online curiosities, living museums (and ultimately mausoleums) of our culture’s enthusiasms. Facebook petrifies the events, likes and passing moods of all our yesterdays into public archives. We are now our own obituarists, curating and narrating our lives with their very passing.

Storytelling has undergone a revolution of access, but has not in itself fundamentally changed. What has changed is the ability of story consumers to become story creators and publishers, and for amateur gossipers to circulate their stories on a previously unimaginable scale. This is changing the profile of the story landscape as I’ve mapped it out. As the technologies and influence of what once belonged exclusively to the Story Business are used to fulfil the Story Impulse of millions, the borders of these two spheres are eroding and becoming increasingly blurred. The everyday world of nonprofessional, anecdotal exchange is in the ascendant. It is eclipsing in volume, and perhaps even influence, the products of professional storytellers and narrative influencers. If the first two spheres are merging, where does that leave the third and final sphere? How does this revolution in storytelling affect the Business Story?

The evolution of branding

The timeline for the third sphere is the newest, and emerges in the period that witnessed the consolidation of intellectual property for authors and artists. The copyright phase of the Story Business overlaps with, and emerges from, the same commercial context that saw the birth of branding, and the stories that developed to promote this new phenomenon.

Brands emerged as symbols to identify goods, and stories accompanied these symbols in the form of advertising. These stories allowed ideas and emotions to be associated with these brands and thus enhance their value and promote their relevance to people’s lives. Brands evolved from symbols into concepts. In time they became the sum of the ideas and perceptions (derived through experiences) that people formed about a product, service or organisation. Brands acquired meanings, and through these meanings articulated their relevance to people’s lives.

Yet these explicit meanings were largely engineered by the marketers who dominated the media through which the ideas, emotions and stories associated with these brands were disseminated. The Business Story, like the Story Business, operated within the ‘Broadcast’ tradition, and relied on many of the same media of transmission. Declared brand meaning was primarily a one-way street, communicated through the marketing messages and narratives that gave shape to the ideas, emotions and experiences the brands were devised to convey.

Brands have always needed stories to convey their meanings. They have always generated stories too. As the most powerful works of fiction have given rise to countless sequels, offshoots and reincarnations, so the most iconic brands have generated more stories than they have told. Nike’s ‘Just do it’ is the consummate consumer story generator. It is not the company’s story, but the potential story of millions of individuals who respond to its clarion call. ‘It’ takes as many narrative shapes as the individual aspirations it reflects or inspires. It is not Nike’s story, but a pre-existing myth the brand has made its own. The American Dream, no less, expressed in three monosyllables, and reinforced in a million stories of personal empowerment. Nike’s own empowerment as a brand and a company is fuelled by these stories.

Yet, before the web and the social web, the impact and visibility of such stories were limited. They resided in the imaginations or memories of individuals, whilst anecdote or advocacy was confined to immediate word-of-mouth grapevines, and destined to die out as oral or personal ephemera. With this access revolution in storytelling, the oral becomes viral, and the personal becomes public and permanent. Instead of brands using stories to convey their meanings, stories are determining the meanings of brands. Brands are becoming the sum of the anecdotes circulated about them. And as there are more consumers out there than brands, campaigns or company-endorsed messages, there are potentially more consumer-generated stories circulating about a brand than those officially endorsed by its owner. If an anecdote can found a brand’s story – a foundation myth, a moment of truth – then, through the amplification of social media, it can re-make or break it too. Brand has always been what people say it is; now those people have a much bigger and more impactful say.

Instead of customers passively consuming messages and actively purchasing goods or services, they can actively create and circulate their own stories. This has much more potential influence on a brand’s fortunes than the official story. Brands came into their own during the industrial epoch in response to problems created by mass urbanisation. In the vast sprawling cities, no one knew whom to trust when purchasing goods or services. Compared with life in villages, there was little visibility, memory, relationship, gossip to enforce accountability, and so little trust. Brands stepped in to fulfil these needs.

Yet mass connectivity potentially makes the whole world a village again. We gather round the virtual global marketplace, conversations flow, relationships are built. Everything is visible, everything is traceable, everyone is accountable because gossip reigns supreme. We know whom to trust: our networks. The problem that branding emerged to solve is therefore no longer so urgently apparent. As long as there is competition there will be a need for branding; yet the concept has to evolve if it is to remain relevant to audiences who can now participate in the creation and circulation of meaning. Storytelling can provide the solution, but storytelling adapted to the new landscape of empowered co-creative participation.

The evolution of corporate storytelling?

A high-profile example of this happening is Coca-Cola’s content marketing manifesto, ‘Liquid and Linked’, launched in April 2011. Coke calculated that only ten percent of the content about its brands on popular sites such as YouTube was actually produced by the company. Coke’s response was to start actively engaging such users as co-creative partners in its story. The company describes this move as: “a big step in the way we interact with consumers ... moving from one-way messages… to creating engaging experiences and back-and-forth dialogue” about its brands. For as they concede: “no one has the smarts on ideas”. So they are now listening to consumer ideas and input, and involving them as participants in the meanings of their brands. “Liquid and Linked ideas must provoke conversations and then The Coca-Cola Company must react to those conversations 365 days a year”. This dynamic approach signals what Coke sees as the “evolution of storytelling” for the company. The global Goliath of brand promotion starts to put its Broadcast days behind it.

It makes a lot of sense for consumer brands to go with the narrative flow. Brands have always craved meaning, and need to maintain their relevance. Here is the means to achieve both, combining viral advocacy and market testing in one fell swoop. Indeed, Coke refers to market data as the “the new soil in which our ideas will grow, and data whisperers will become the new messiahs”.

Yet, this is actually The Coca-Cola Company talking here. Its new manifesto is designed to involve all its stakeholders from consumers to investors in the telling of its story. A bold corporate ambition is behind these changes. As it declares: “The Coca-Cola Company intends to double the size of the business between now and 2020 and so that means that every single marketing norm needs to be reconsidered if we’re going to meet such aggressive volume and business growth objectives”. ‘Liquid and Linked’ is the result of this radical rethink, and sees the company moving from being about “creative excellence to content excellence”. Or, from a producer and promoter of world-dominating brands to a circulator of stories.

A major step in this direction was taken in November 2012 (just as I thought I was finishing this book), with the complete reinvention of Coca-Cola’s corporate website, as an interactive magazine. Whilst retaining the same url – http://www.coca-colacompany.com/ – the site has been rebranded as Coca-Cola Journey (what else?), and launched as a story-sharing hub for the company and its brands.

Story is everywhere you look on Journey. It is the first item on the primary navigation, where ‘About us’ is usually found, and is the dominant focus of a homepage that is continually refreshed with new rich content. Instead of the hero shots broadcasting corporate messages, they instead share stories through video, blogs or social media feeds. Coca-Cola is still very much the star of the show. But then, Journey was originally an internal magazine, reinvented as the company’s principal corporate communications hub. As a spokesman explains: “We had brand pages, but there was nothing that knitted it all together into the story of us... So we wanted to take all that great storytelling that we were sharing internally and share it with the world.”

Coke has a lot of history and vast operations, and so there is a lot of Coke content to share around. Whilst the content is Coke themed, it’s anything but dry corporate monologue. There are Coke-themed recipes; innovation videos about bottling materials told from a human perspective; archive memorabilia; Sustainability stories about what Coke calls its ‘community’ around the world; investor information and ‘Business’ stories and opinions; and people features drawn from its 700,000 plus employee base. Coke has a lot to say, but it also has over 50 million Facebook fans, and is actively engaging with them and other social media communities to involve them in the Journey. There are imbedded customised social media feeds throughout, systematic cross-pollination of content across the main social media sites, and a coordinated effort to encourage inbound traffic to its story-sharing hub. Inbound and outbound, everything is brought together through storytelling.

This is what ‘Liquid and Linked’ is all about. ‘Liquid’ is about circulation of content. If the content isn’t compelling enough no one is going to share it. And if they can’t tell their story on the most basic mobile phone, then, in the words of a Coke spokeswoman, “we haven’t finished telling our story”. Which is where ‘Linked’ comes in. Whilst its content needs to circulate freely, this content must flow from and back to a clear brand strategy and a coherent idea. That idea is ‘Open Happiness’, the latest iteration of Coke’s consumer strapline, and the single-minded focus of their new content marketing crusade. As Coke explains: “The role of Content Excellence is to behave like a ruthless editor otherwise we’ll risk just creating noise.” Coca-Cola is thus applying the same ‘ruthless’ efficiency that has always characterised its brand management to its new incarnation as global storyteller.

Everything joins up, and everyone joins in, invited to be part of the Journey. This is not just a consumer brand paying lip service to an empowered demographic it wants to target. Not just. This is one of the world’s biggest companies throwing open its principal corporate communication channel to involve all its audiences in the same story. Coke has multiple stakeholders and audiences, yet Journey makes little attempt to segregate them along approved corporate lines.

Investors rub shoulders with brand fans as part of a single community. Should the latter stray into the investor section they might encounter the following compliance jargon – “The following presentation may include certain ‘non-GAAP financial measures’ as defined in Regulation G under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934”. Not much happiness there. Or should they discover that the company’s declared vision is summed up in a single word – that isn’t ‘Happiness’, but ‘Profit’ – they might briefly pause for thought. But on the other side of the coin, the investment community is given a clear demonstration of the value and currency of consistent storytelling. An ambitious growth target demands a single-minded narrative strategy. Yet Coke knows that storytelling is the universal human imperative: “at the heart of all families, communities and cultures and it’s something that The Coca-Cola Company has excelled at for 125 years”. And therefore in this new age of global conversations, narrative provides the best way to realise Coke’s long cherished dream of being a universal currency. Teaching the world to sing its story through the channels of empowered amplification.

Only connect

Coke’s evolution into a storyteller perhaps marks a more significant evolution still: the evolution of branding from being about managing assets to sharing stories. This, I believe, is what’s happening, and why the age-old arts of storytelling are newly relevant and urgently required. Even here, finally in the most resistant corner of the Business Story sphere: corporate communications. The corporate brand, like its consumer counterpart, must evolve if it is to remain relevant to those upon whom it ultimately depends. It must evolve into a storyteller.

Consumer brands have traditionally thrived through storytelling, creating works of narrative art in the form of advertising. The empowerment of users and audiences has compelled them to momentarily pause in their relentless monologue, and start listening… before rejoining what is now a conversation. As one content curation pundit perfectly summed it up, “When it comes to social content, you have to be more interesting than your audiences’ friends”. The brands that seek to start conversations have to be prepared to listen and respond to them too. Even the most interesting interruption is still an interruption if it doesn’t allow co-creative input to define a brand’s meaning and sharing its story.

Consumer brands have been searching for meaning for a long time. At first they needed to be merely preferred. Then they needed to be loved. Now they need to be shared. But brands are largely abstractions, made meaningful and tangible through experience. Experience leads to anecdote and through anecdote, advocacy. Sharing brand stories ultimately gives the brands the meaning they have always craved. Brings them to life, proves their relevance, gives them a voice. Product brands do not actually have voices (despite the infantalist babble of Innocent wannabes). But consumers do, and it’s right that they should have a major say in the brand’s meaning. A product brand can ultimately be what consumers say it is, and lose none of its identify or relevance. Quite the opposite. If the meanings it generates are positive and lead to advocacy then the brand has served its purpose. Like the best stories, it provides a mirror, reflecting the needs and desires of those with whom it interacts.

In this model, products and their promotion are no longer an industrial pipeline. But rather a grapevine, to be cultivated, harvested and showcased as living testimony to their relevance to consumers. The proof of the product is in the narratives that blossom around it. In this brave new world, stories do not so much promote brands, as provide vehicles for their meaning. If a product generates a lot of positive stories, then it is the proof of its relevance and resonance. These stories become part of the brand’s own story. No longer abstractions associated with artificial needs, but the authentic, organic meanings expressed through the stories they give rise to. By entering into co-creative conversation, consumer brands future-proof their relevance for the networked generations.

If consumer brands need to listen, corporate brands need to talk. Whilst a product doesn’t actually have a voice, a company does. And it needs to find it and use this far more effectively: by telling its story.

What the corporate world needs most, story does best: establish the human connections upon which trust is built. That doesn’t mean every brand must or can afford to become a ‘publisher’ as many are now claiming. So much as being absolutely clear on what its core story has to say, and why this ultimately matters. Whilst consumer brands can be mercurially adaptive to the flow of conversations, the corporate brand needs to be far more focused, single-minded and, above all, articulate in the way it tells its story. Without a product, there are only relationships and experiences, and these can best be nurtured and expressed through narrative. The corporate brand has to adopt the role of storyteller if it is to fulfil its function where it is most needed. In fact, there has never been a greater need for the corporate brand, and a greater opportunity to serve its purpose through storytelling.

If a company doesn’t tell its story there are likely to be plenty of others who will. This may not be quite the story the company wants to share; but if it has more clarity, volume and visibility than the messages the company itself sends, then this will stand for its story. Silence is not an option in this connected world of clamorous chatter. It only exacerbates mistrust, and ultimately isolation. A company has to put its story out there with clarity and conviction. It has to start the conversation with an articulate proposition, and ensure this holds up coherently, and flows consistently through all the channels of engagement.

If the core brand story is an authentic reflection of who it truly is, then the stories this gives rise to, the connections this makes, should be honest reflections too. A positive feedback loop will be established, endorsing and amplifying the narrative the company seeks to share. If the story needs to evolve, then so be it. It has to go out there and live in the imaginations and advocacy of those with whom it needs to connect. If it is flatly rejected, then this probably indicates that there is no substance to it. Then it must be rethought and redefined. The days of monologue are over.

As long as there is competition there will be a need for brands. Differentiation is still required. But this differentiation will be built on the meaningfulness of relationships. And this relationship will be truly that: a dynamic, mutually-beneficial connection, where all sides relate to and with the meaning of the brand. Brand may no longer be a thing, but a process. A verb more than a noun. A journey, experienced as story.

A shared story is not just something that connects with people, it is the connection – the trace of the brand’s relevance, the narrative testament to its value and its truth. Corporate identity can live up to its name if it finds a human voice, a coherent sense of self, and an articulate, engaging expression of that self through the stories it shares. In this way story ultimately fulfils the promise of brand. It connects rationally, because there will be a clear integrity of idea and its expression; and emotionally, because the defined need it serves will get to the very core of what it means to be human. Story is the universal human connector.

A connected world demands a connected currency. Story has always played this role. Its true domain is the imagination, its true vehicle is the flow and exchange of ideas, circulating and surviving as a currency with the power to change how people think, feel and act. Ultimately a power to change the world. Stories were ‘viral’ before the metaphor became a buzzword. The conditions are now right for an epidemic of narrative. The Internet and social web are simply testimony to the human urge to narrative, to make connections through the currency of human relationships that is storytelling.

The Story Impulse is as strong as it has ever been, and can now be expressed through the means and media that once belonged exclusively to the Story Business. As these two spheres merge into one, there is one natural course for the corporate world to take – and that is to connect with the world of human beings through storytelling. As spheres one and two increasingly converge, becoming a universal zone of empowered, connected narrative, story is set to conquer its final frontier: the corporate world. Business must now connect with the world upon which it ultimately depends. Then there will be one sphere, one world, brought together through storytelling.

There really only is one world. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect.