preface:

A Tale of Two CVs

I’ll start by sharing my own story. Or, rather, ‘stories’.

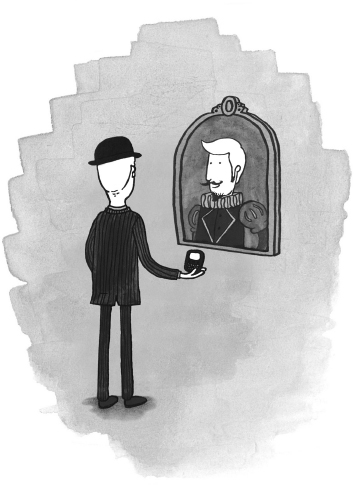

For some years now I’ve maintained two CVs. The first tells how I was once a fellow in English Literature at an Oxford College, and then the editor of the Penguin Classics series. It lists the books I have written, including an academic study of Victorian Gothic fiction (of interest to about 100 people on the planet); a biography of the Romantic poet John Keats; and my introductions to works by the likes of Oscar Wilde and William Shakespeare. There’s also a cultural history of sunshine I wrote about an obsession of mine. But like everything on this CV, it has nothing to do with how I earn my living. Which is why I need a second CV.

After Penguin, I stumbled into corporate branding, where I have worked ever since. An old friend needed some extra brainpower for a naming project his agency was working on. “You’re good at words”, he reasoned, “and it’s words we need urgently”. So I gave it a bash, spun out a long list, and the agency liked what I did. So much, that they offered me a job as a consultant. I told them I knew very little about branding, and even less about the world of business it was there to brand. But they saw potential and took a chance. And so, here I am many years later, with a second CV telling a very different story.

My two CVs reflect a broader divide in Anglo-American society, where there simmers a mutual suspicion, even hostility, between art and commerce, high culture and high finance. This division goes back at least to the Victorian age, when the new captains of industry consciously rejected the effete, dying world of the aristocracy. Many were religious non-conformists, which meant they were excluded from Oxbridge, which only admitted Anglicans, and where the study of Greek and Roman classics was considered an essential part of a gentleman’s education. When the poet Matthew Arnold’s Culture and Anarchy (1869) coined the term ‘Philistines’ to characterise these industrialists’ indifference to culture in pursuit of profit the label stuck, and the lines were irrevocably drawn.

In many ways, business is quite happy to embrace the Philistine label, as it conforms to its self-image of seriousness and the hard-nosed domination of something it calls the ‘real world’. At Penguin I encountered these divisions at first hand. My job was to preserve and promote the world’s literary riches, yet within a commercial imprint ultimately answerable to Pearson’s shareholders. And much more recently, I learnt that one of the reasons we had been unsuccessful in an Annual Report pitch I took part in was my reference to Romeo and Juliet during the pitch presentation. Shakespeare, it was felt, was not a fitting subject for the boardroom, or the serious business of investor relations. (To be fair, they also mentioned my suede shoes, the patches on my jacket sleeves, and the fact that I stood up and walked about a bit when I presented. Let’s face it, they really didn’t like me.) And so when I forsook the literary world for corporate branding, it was clear to me that I would need to leave all that soft stuff behind me. The two realms symbolised by my two CVs looked destined to remain separate forever.

But developments in my career and within the communications sphere have brought about their partial reconciliation. In 2008, I joined a communications agency based in Shoreditch, London called Radley Yeldar. They started out in Annual Reporting in 1986, and now work across a broad spectrum of communications, including Moving Image, Employee Engagement, Digital, Brand, and Sustainability communications. As the agency evolved it developed a common principle and philosophy to connect these skills. Story is that connection.

After all, they were pioneers in, what was back then, the new idea of ‘narrative’ reporting. This is where a company seeks to provide a coherent account of its performance through word and image, rather than just numbers. Standard practice now, but testimony to the fact that story plays a big part in Radley Yeldar’s own story. And because it was also a big part of mine, I soon found myself working across all these disciplines and employing skills and knowledge I had relegated to my other CV. As story became the focus of my work again, I found a natural fit between what branding and communications sought to achieve, and what the greatest works of literature had in common. At Penguin I had seen how many of their big name authors – Tom Clancy, Nick Hornby, Maeve Binchy – made millions by the power of their names. I knew storytellers could be brands. I now realised brands could also be storytellers.

Clients were also starting to talk about ‘story’, and it was beginning to open doors that had been resolutely shut to ‘brand’. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been pulled aside before entering a boardroom, and conspiratorially enjoined by a nervous marketing manager not to mention the ‘B word’ before the CEO. Brand, for all the claims and efforts of its professional advocates, is often still associated in the C-Suite with logos. The sole responsibility of the marketing department, to be interfered with and spent money on only under duress. Yet many of the very same companies where brand was a forbidden word were happy to talk openly about “getting their story straight”. Happy to see it play a role very like that of brand in its more all-encompassing mission, but applied directly to a specific communications need.

Things are definitely changing, with ‘story’ becoming something of a buzzword in communications and marketing. In America it is even more established, with one recent book claiming that “many of the most successful organizations on the planet intentionally use storytelling as a key leadership tool”. Yet there’s still a long way to go over here. For if European companies are following their US counterparts by assigning a “high-level ‘corporate storyteller’ to capture and share their most important stories”, then they are clearly keeping these stories to themselves. For every company that embraces storytelling there must be countless others who believe Shakespeare or similar has no place in the boardroom, or nothing to contribute to their world.

How story can help businesses communicate better is what this book is all about. Unlike many books designed for business audiences, mine does not claim to offer groundbreaking revelations or newly minted secrets to success. I have not seen the future, nor can I promise to get you there quicker. In fact, what I want to share is not new at all, rather, very old indeed. There are no secrets to impart. As Robert McKee puts it in his classic screenwriting primer Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting “In the twenty-three centuries since Aristotle wrote The Poetics, the ‘secrets’ of story have been as public as the library down the street”.

Nor is there any mystery to why storytelling has a role in business communications. It belongs here because telling stories is part of what it means to be human. There is not a culture on this earth that does not tell, exchange and enjoy stories.

Story is simply effective communication. It allows humans to connect powerfully with each other, and share information about what it is to be human; whether they are sitting in the auditorium of a theatre, or behind the polished walnut table of a successful company. As a literary critic turned brand consultant/corporate storyteller, I do not seek to translate the secrets of one world into the other. Rather, I want to stress that there is only one world, and one basic psychology that has not evolved one jot since it became recognisably human, and started to share stories. Why they have this power, what they have in common, and what we can learn from this to help business communicate better, is what this book is about.

The following does not hail from my literary CV, nor from my communications one. But from a space where they connect and overlap. It is my belief that maintaining two CVs reflects false divisions and denies rich opportunities. I hope one day to make my two CVs one. That is the goal of the journey I now propose we take together.