![]()

Patterns for Flexible Object Programming

With strategies for generating objects covered, we’re free now to look at some strategies for structuring classes and objects. I will focus in particular on the principle that composition provides greater flexibility than inheritance. The patterns I examine in this chapter are once again drawn from the Gang of Four catalog.

This chapter will cover:

- The Composite pattern: Composing structures in which groups of objects can be used as if they were individual objects

- The Decorator pattern: A flexible mechanism for combining objects at runtime to extend functionality

- The Facade pattern: Creating a simple interface to complex or variable systems

Structuring Classes to Allow Flexible Objects

Way back in Chapter 4, I said that beginners often confuse objects and classes. This was only half true. In fact, most of the rest of us occasionally scratch our heads over UML class diagrams, attempting to reconcile the static inheritance structures they show with the dynamic object relationships their objects will enter into off the page.

Remember the pattern principle “Favor composition over inheritance”? This principle distills this tension between the organization of classes and of objects. In order to build flexibility into our projects, we structure our classes so that their objects can be composed into useful structures at runtime.

This is a common theme running through the first two patterns of this chapter. Inheritance is an important feature in both, but part of its importance lies in providing the mechanism by which composition can be used to represent structures and extend functionality.

The Composite Pattern

The Composite pattern is perhaps the most extreme example of inheritance deployed in the service of composition. It is a simple and yet breathtakingly elegant design. It is also fantastically useful. Be warned, though, it is so neat, you might be tempted to overuse this strategy.

The Composite pattern is a simple way of aggregating and then managing groups of similar objects so that an individual object is indistinguishable to a client from a collection of objects. The pattern is, in fact, very simple, but it is also often confusing. One reason for this is the similarity in structure of the classes in the pattern to the organization of its objects. Inheritance hierarchies are trees, beginning with the super class at the root, and branching out into specialized subclasses. The inheritance tree of classes laid down by the Composite pattern is designed to allow the easy generation and traversal of a tree of objects.

If you are not already familiar with this pattern, you have every right to feel confused at this point. Let’s try an analogy to illustrate the way that single entities can be treated in the same way as collections of things. Given broadly irreducible ingredients such as cereals and meat (or soya if you prefer), we can make a food product—a sausage, for example. We then act on the result as a single entity. Just as we eat, cook, buy, or sell meat, we can eat, cook, buy, or sell the sausage that the meat in part composes. We might take the sausage and combine it with the other composite ingredients to make a pie, thereby rolling a composite into a larger composite. We behave in the same way to the collection as we do to the parts. The Composite pattern helps us to model this relationship between collections and components in our code.

The Problem

Managing groups of objects can be quite a complex task, especially if the objects in question might also contain objects of their own. This kind of problem is very common in coding. Think of invoices, with line items that summarize additional products or services, or things-to-do lists with items that themselves contain multiple subtasks. In content management, we can’t move for trees of sections, pages, articles, media components. Managing these structures from the outside can quickly become daunting.

Let’s return to a previous scenario. I am designing a system based on a game called Civilization. A player can move units around hundreds of tiles that make up a map. Individual counters can be grouped together to move, fight, and defend themselves as a unit. Here I define a couple of unit types:

abstract class Unit {

abstract function bombardStrength();

}

class Archer extends Unit {

function bombardStrength() {

return 4;

}

}

class LaserCannonUnit extends Unit {

function bombardStrength() {

return 44;

}

}

The Unit class defines an abstract bombardStrength() method, which sets the attack strength of a unit bombarding an adjacent tile. I implement this in both the Archer and LaserCannonUnit classes. These classes would also contain information about movement and defensive capabilities, but I’ll keep things simple. I could define a separate class to group units together like this:

class Army {

private $units = array();

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

array_push( $this->units, $unit );

}

function bombardStrength() {

$ret = 0;

foreach( $this->units as $unit ) {

$ret += $unit->bombardStrength();

}

return $ret;

}

}

The Army class has an addUnit() method that accepts a Unit object. Unit objects are stored in an array property called $units. I calculate the combined strength of my army in the bombardStrength() method. This simply iterates through the aggregated Unit objects, calling the bombardStrength() method of each one.

This model is perfectly acceptable as long as the problem remains as simple as this. What happens, though, if I were to add some new requirements? Let’s say that an army should be able to combine with other armies. Each army should retain its own identity so that it can disentangle itself from the whole at a later date. The ArchDuke’s brave forces may have common cause today with General Soames’s push toward the exposed flank of the enemy, but a domestic rebellion may send his army scurrying home at any time. For this reason, I can’t just decant the units from each army into a new force.

I could amend the Army class to accept Army objects as well as Unit objects:

function addArmy( Army $army ) {

array_push( $this->armies, $army );

}

Then I’d need to amend the bombardStrength() method to iterate through all armies as well as units:

function bombardStrength() {

$ret = 0;

foreach( $this->units as $unit ) {

$ret += $unit->bombardStrength();

}

foreach( $this->armies as $army ) {

$ret += $army->bombardStrength();

}

return $ret;

}

This additional complexity is not too problematic at the moment. Remember, though, I would need to do something similar in methods like defensiveStrength(), movementRange(), and so on. My game is going to be richly featured. Already the business group is calling for troop carriers that can hold up to ten units to improve their movement range on certain terrains. Clearly, a troop carrier is similar to an army in that it groups units. It also has its own characteristics. I could further amend the Army class to handle TroopCarrier objects, but I know that there will be a need for still more unit groupings. It is clear that I need a more flexible model.

Let’s look again at the model I have been building. All the classes I created shared the need for a bombardStrength() method. In effect, a client does not need to distinguish between an army, a unit, or a troop carrier. They are functionally identical. They need to move, attack, and defend. Those objects that contain others need to provide methods for adding and removing. These similarities lead us to an inevitable conclusion. Because container objects share an interface with the objects that they contain, they are naturally suited to share a type family.

Implementation

The Composite pattern defines a single inheritance hierarchy that lays down two distinct sets of responsibilities. We have already seen both of these in our example. Classes in the pattern must support a common set of operations as their primary responsibility. For us, that means the bombardStrength() method. Classes must also support methods for adding and removing child objects.

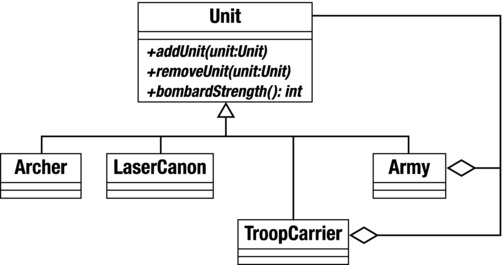

Figure 10-1 shows a class diagram that illustrates the Composite pattern as applied to our problem.

Figure 10-1. The Composite pattern

As you can see, all the units in this model extend the Unit class. A client can be sure, then, that any Unit object will support the bombardStrength() method. So an Army can be treated in exactly the same way as an Archer.

The Army and TroopCarrier classes are composites: designed to hold Unit objects. The Archer and LaserCannon classes are leaves, designed to support unit operations but not to hold other Unit objects. There is actually an issue as to whether leaves should honor the same interface as composites as they do in Figure 10-1. The diagram shows TroopCarrier and Army aggregating other units, even though the leaf classes are also bound to implement addUnit(), I will return to this question shortly. Here is the abstract Unit class:

abstract class Unit {

abstract function addUnit( Unit $unit );

abstract function removeUnit( Unit $unit );

abstract function bombardStrength();

}

As you can see, I lay down the basic functionality for all Unit objects here. Now, let’s see how a composite object might implement these abstract methods:

class Army extends Unit {

private $units = array();

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

if ( in_array( $unit, $this->units, true ) ) {

return;

}

$this->units[] = $unit;

}

function removeUnit( Unit $unit ) {

$this->units = array_udiff( $this->units, array( $unit ),

function( $a, $b ) { return ($a === $b)?0:1; } );

}

function bombardStrength() {

$ret = 0;

foreach( $this->units as $unit ) {

$ret += $unit->bombardStrength();

}

return $ret;

}

}

The addUnit() method checks that I have not yet added the same Unit object before storing it in the private $units array property. removeUnit() uses a similar check to remove a given Unit object from the property.

![]() Note I use an anonymous callback function in the removeUnit() method. This checks the array elements in the $units property for equivalence. If you're running an older version of PHP, you can use the create_function() method to get a similar effect:

Note I use an anonymous callback function in the removeUnit() method. This checks the array elements in the $units property for equivalence. If you're running an older version of PHP, you can use the create_function() method to get a similar effect:

$this->units = array_udiff( $this->units, array( $unit ),

create_function( '$a,$b', 'return ($a === $b)?0:1;' ) );

Army objects, then, can store Units of any kind, including other Army objects, or leaves such as Archer or LaserCannonUnit. Because all units are guaranteed to support bombardStrength(), our Army::bombardStrength() method simply iterates through all the child Unit objects stored in the $units property, calling the same method on each.

One problematic aspect of the Composite pattern is the implementation of add and remove functionality. The classic pattern places add() and remove() methods in the abstract super class. This ensures that all classes in the pattern share a common interface. As you can see here, though, it also means that leaf classes must provide an implementation:

class UnitException extends Exception {}

class Archer extends Unit {

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

throw new UnitException( get_class($this)." is a leaf" );

}

function removeUnit( Unit $unit ) {

throw new UnitException( get_class($this)." is a leaf" );

}

function bombardStrength() {

return 4;

}

}

I do not want to make it possible to add a Unit object to an Archer object, so I throw exceptions if addUnit() or removeUnit() are called. I will need to do this for all leaf objects, so I could perhaps improve my design by replacing the abstract addUnit()/removeUnit() methods in Unit with default implementations like the one in the preceding example:

abstract class Unit {

abstract function bombardStrength();

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

throw new UnitException( get_class($this)." is a leaf" );

}

function removeUnit( Unit $unit ) {

throw new UnitException( get_class($this)." is a leaf" );

}

}

class Archer extends Unit {

function bombardStrength() {

return 4;

}

}

This removes duplication in leaf classes but has the drawback that a Composite is not forced at compile time to provide an implementation of addUnit() and removeUnit(), which could cause problems down the line.

I will look in more detail at some of the problems presented by the Composite pattern in the next section. Let’s end this section by examining of some of its benefits.

- Flexibility: Because everything in the Composite pattern shares a common supertype, it is very easy to add new composite or leaf objects to the design without changing a program’s wider context.

- Simplicity: A client using a Composite structure has a straightforward interface. There is no need for a client to distinguish between an object that is composed of others and a leaf object (except when adding new components). A call to Army::bombardStrength() may cause a cascade of delegated calls behind the scenes, but to the client, the process and result are exactly equivalent to those associated with calling Archer::bombardStrength().

- Implicit reach: Objects in the Composite pattern are organized in a tree. Each composite holds references to its children. An operation on a particular part of the tree, therefore, can have a wide effect. We might remove a single Army object from its Army parent and add it to another. This simple act is wrought on one object, but it has the effect of changing the status of the Army object’s referenced Unit objects and of their own children.

- Explicit reach: Tree structures are easy to traverse. They can be iterated through in order to gain information or to perform transformations. We will look at a particularly powerful technique for this in the next chapter when we deal with the Visitor pattern.

Often you really see the benefit of a pattern only from the client’s perspective, so here are a couple of armies:

// create an army

$main_army = new Army();

// add some units

$main_army->addUnit( new Archer() );

$main_army->addUnit( new LaserCannonUnit() );

// create a new army

$sub_army = new Army();

// add some units

$sub_army->addUnit( new Archer() );

$sub_army->addUnit( new Archer() );

$sub_army->addUnit( new Archer() );

// add the second army to the first

$main_army->addUnit( $sub_army );

// all the calculations handled behind the scenes

print "attacking with strength: {$main_army->bombardStrength()} ";

I create a new Army object and add some primitive Unit objects. I repeat the process for a second Army object that I then add to the first. When I call Unit::bombardStrength() on the first Army object, all the complexity of the structure that I have built up is entirely hidden.

If you’re anything like me, you would have heard alarm bells ringing when you saw the code extract for the Archer class. Why do we put up with these redundant addUnit() and removeUnit() methods in leaf classes that do not need to support them? An answer of sorts lies in the transparency of the Unit type.

If a client is passed a Unit object, it knows that the addUnit() method will be present. The Composite pattern principle that primitive (leaf) classes have the same interface as composites is upheld. This does not actually help you much, because you still do not know how safe you might be calling addUnit() on any Unit object you might come across.

If I move these add/remove methods down so that they are available only to composite classes, then passing a Unit object to a method leaves me with the problem that I do not know by default whether or not it supports addUnit(). Nevertheless, leaving booby-trapped methods lying around in leaf classes makes me uncomfortable. It adds no value and confuses a system’s design, because the interface effectively lies about its own functionality.

You can split composite classes off into their own CompositeUnit subtype quite easily. First of all, I excise the add/remove behavior from Unit:

abstract class Unit {

function getComposite() {

return null;

}

abstract function bombardStrength();

}

Notice the new getComposite() method. I will return to this in a little while. Now, I need a new abstract class to hold addUnit() and removeUnit(). I can even provide default implementations:

abstract class CompositeUnit extends Unit {

private $units = array();

function getComposite() {

return $this;

}

protected function units() {

return $this->units;

}

function removeUnit( Unit $unit ) {

$this->units = array_udiff( $this->units, array( $unit ),

function( $a, $b ) { return ($a === $b)?0:1; } );

}

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

if ( in_array( $unit, $this->units, true ) ) {

return;

}

$this->units[] = $unit;

}

}

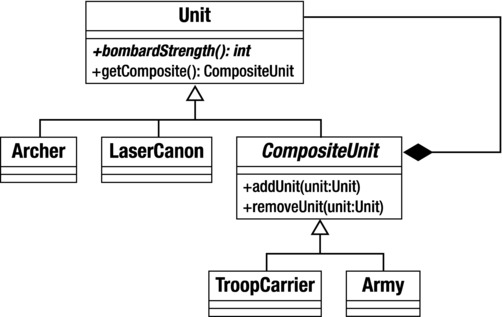

The CompositeUnit class is declared abstract, even though it does not itself declare an abstract method. It does, however, extend Unit, and does not implement the abstract bombardStrength() method. Army (and any other composite classes) can now extend CompositeUnit. The classes in my example are now organized as in Figure 10-2.

Figure 10-2. Moving add/remove methods out of the base class

The annoying, useless implementations of add/remove methods in the leaf classes are gone, but the client must still check to see whether it has a CompositeUnit before it can use addUnit().

This is where the getComposite() method comes into its own. By default, this method returns a null value. Only in a CompositeUnit class does it return CompositeUnit. So if a call to this method returns an object, we should be able to call addUnit() on it. Here’s a client that uses this technique:

class UnitScript {

static function joinExisting( Unit $newUnit,

Unit $occupyingUnit ) {

$comp;

if ( ! is_null( $comp = $occupyingUnit->getComposite() ) ) {

$comp->addUnit( $newUnit );

} else {

$comp = new Army();

$comp->addUnit( $occupyingUnit );

$comp->addUnit( $newUnit );

}

return $comp;

}

}

The joinExisting() method accepts two Unit objects. The first is a newcomer to a tile, and the second is a prior occupier. If the second Unit is a CompositeUnit, then the first will attempt to join it. If not, then a new Army will be created to cover both units. I have no way of knowing at first whether the $occupyingUnit argument contains a CompositeUnit. A call to getComposite() settles the matter, though. If getComposite() returns an object, I can add the new Unit object to it directly. If not, I create the new Army object and add both.

I could simplify this model further by having the Unit::getComposite() method return an Army object prepopulated with the current Unit. Or I could return to the previous model (which did not distinguish structurally between composite and leaf objects) and have Unit::addUnit() do the same thing: create an Army object, and add both Unit objects to it. This is neat, but it presupposes that you know in advance the type of composite you would like to use to aggregate your units. Your business logic will determine the kinds of assumptions you can make when you design methods like getComposite() and addUnit().

These contortions are symptomatic of a drawback to the Composite pattern. Simplicity is achieved by ensuring that all classes are derived from a common base. The benefit of simplicity is sometimes bought at a cost to type safety. The more complex your model becomes, the more manual type checking you are likely to have to do. Let’s say that I have a Cavalry object. If the rules of the game state that you cannot put a horse on a troop carrier, I have no automatic way of enforcing this with the Composite pattern:

class TroopCarrier {

function addUnit( Unit $unit ) {

if ( $unit instanceof Cavalry ) {

throw new UnitException("Can't get a horse on the vehicle");

}

super::addUnit( $unit );

}

function bombardStrength() {

return 0;

}

}

I am forced to use the instanceof operator to test the type of the object passed to addUnit(). Too many special cases of this kind, and the drawbacks of the pattern begin to outweigh its benefits. Composite works best when most of the components are interchangeable.

Another issue to bear in mind is the cost of some Composite operations. The Army::bombardStrength() method is typical in that it sets off a cascade of calls to the same method down the tree. For a large tree with lots of subarmies, a single call can cause an avalanche behind the scenes. bombardStrength() is not itself very expensive, but what would happen if some leaves performed a complex calculation to arrive at their return values? One way around this problem is to cache the result of a method call of this sort in the parent object, so that subsequent invocations are less expensive. You need to be careful, though, to ensure that the cached value does not grow stale. You should devise strategies to wipe any caches whenever any operations take place on the tree. This may require that you give child objects references to their parents.

Finally, a note about persistence. The Composite pattern is elegant, but it doesn’t lend itself neatly to storage in a relational database. This is because, by default, you access the entire structure only through a cascade of references. So to construct a Composite structure from a database in the natural way you would have to make multiple expensive queries. You can get round this problem by assigning an ID to the whole tree, so that all components can be drawn from the database in one go. Having acquired all the objects, however, you would still have the task of recreating the parent/child references which themselves would have to be stored in the database. This is not difficult, but it is somewhat messy.

Although Composites sit uneasily with relational databases, they lend themselves very well indeed to storage in XML. This is because XML elements are often themselves composed of trees of subelements.

Composite in Summary

So the Composite pattern is useful when you need to treat a collection of things in the same way as you would an individual, either because the collection is intrinsically like a component (armies and archers), or because the context gives the collection the same characteristics as the component (line items in an invoice). Composites are arranged in trees, so an operation on the whole can affect the parts, and data from the parts is transparently available via the whole. The Composite pattern makes such operations and queries transparent to the client. Trees are easy to traverse (as we shall see in the next chapter). It is easy to add new component types to Composite structures.

On the downside, Composites rely on the similarity of their parts. As soon as we introduce complex rules as to which composite object can hold which set of components, our code can become hard to manage. Composites do not lend themselves well to storage in relational databases but are well suited to XML persistence.

The Decorator Pattern

While the Composite pattern helps us to create a flexible representation of aggregated components, the Decorator pattern uses a similar structure to help us to modify the functionality of concrete components. Once again, the key to this pattern lies in the importance of composition at runtime. Inheritance is a neat way of building on characteristics laid down by a parent class. This neatness can lead you to hard-code variation into your inheritance hierarchies, often causing inflexibility.

The Problem

Building all your functionality into an inheritance structure can result in an explosion of classes in a system. Even worse, as you try to apply similar modifications to different branches of your inheritance tree, you are likely to see duplication emerge.

Let’s return to our game. Here, I define a Tile class and a derived type:

abstract class Tile {

abstract function getWealthFactor();

}

class Plains extends Tile {

private $wealthfactor = 2;

function getWealthFactor() {

return $this->wealthfactor;

}

}

I define a Tile class. This represents a square on which my units might be found. Each tile has certain characteristics. In this example, I have defined a getWealthFactor() method that affects the revenue a particular square might generate if owned by a player. As you can see, Plains objects have a wealth factor of 2. Obviously, tiles manage other data. They might also hold a reference to image information so that the board could be drawn. Once again, I’ll keep things simple here.

I need to modify the behavior of the Plains object to handle the effects of natural resources and human abuse. I wish to model the occurrence of diamonds on the landscape, and the damage caused by pollution. One approach might be to inherit from the Plains object:

class DiamondPlains extends Plains {

function getWealthFactor() {

return parent::getWealthFactor() + 2;

}

}

class PollutedPlains extends Plains {

function getWealthFactor() {

return parent::getWealthFactor() - 4;

}

}

I can now acquire a polluted tile very easily:

$tile = new PollutedPlains();

print $tile->getWealthFactor();

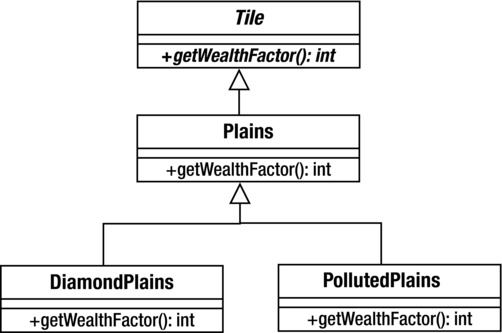

You can see the class diagram for this example in Figure 10-3.

Figure 10-3. Building variation into an inheritance tree

This structure is obviously inflexible. I can get plains with diamonds. I can get polluted plains. But can I get them both? Clearly not, unless I am willing to perpetrate the horror that is PollutedDiamondPlains. This situation can only get worse when I introduce the Forest class which can also have diamonds and pollution.

This is an extreme example, of course, but the point is made. Relying entirely on inheritance to define your functionality can lead to a multiplicity of classes and a tendency toward duplication.

Let’s take a more commonplace example at this point. Serious web applications often have to perform a range of actions on a request before a task is initiated to form a response. You might need to authenticate the user, for example, and to log the request. Perhaps you should process the request to build a data structure from raw input. Finally, you must perform your core processing. You are presented with the same problem.

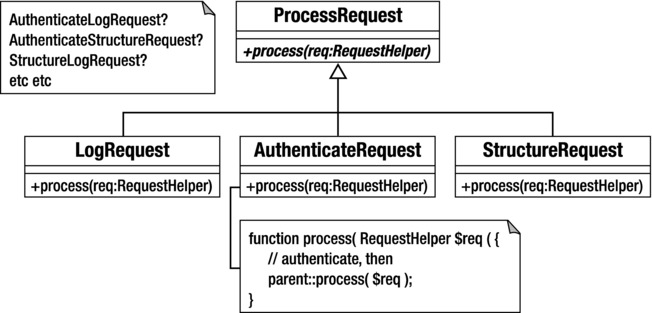

You can extend the functionality of a base ProcessRequest class with additional processing in a derived LogRequest class, in a StructureRequest class, and in an AuthenticateRequest class. You can see this class hierarchy in Figure 10-4.

Figure 10-4. More hard-coded variations

What happens, though, when you need to perform logging and authentication but not data preparation? Do you create a LogAndAuthenticateProcessor class? Clearly, it is time to find a more flexible solution.

Implementation

Rather than use only inheritance to solve the problem of varying functionality, the Decorator pattern uses composition and delegation. In essence, Decorator classes hold an instance of another class of their own type. A Decorator will implement an operation so that it calls the same operation on the object to which it has a reference before (or after) performing its own actions. In this way it is possible to build a pipeline of Decorator objects at runtime.

Let’s rewrite our game example to illustrate this:

abstract class Tile {

abstract function getWealthFactor();

}

class Plains extends Tile {

private $wealthfactor = 2;

function getWealthFactor() {

return $this->wealthfactor;

}

}

abstract class TileDecorator extends Tile {

protected $tile;

function __construct( Tile $tile ) {

$this->tile = $tile;

}

}

Here, I have declared Tile and Plains classes as before but introduced a new class: TileDecorator. This does not implement getWealthFactor(), so it must be declared abstract. I define a constructor that requires a Tile object, which it stores in a property called $tile. I make this property protected so that child classes can gain access to it. Now I’ll redefine the Pollution and Diamond classes:

class DiamondDecorator extends TileDecorator {

function getWealthFactor() {

return $this->tile->getWealthFactor()+2;

}

}

class PollutionDecorator extends TileDecorator {

function getWealthFactor() {

return $this->tile->getWealthFactor()-4;

}

}

Each of these classes extends TileDecorator. This means that they have a reference to a Tile object. When getWealthFactor() is invoked, each of these classes invokes the same method on its Tile reference before making its own adjustment.

By using composition and delegation like this, you make it easy to combine objects at runtime. Because all the objects in the pattern extend Tile, the client does not need to know which combination it is working with. It can be sure that a getWealthFactor() method is available for any Tile object, whether it is decorating another behind the scenes or not.

$tile = new Plains();

print $tile->getWealthFactor(); // 2

Plains is a component. It simply returns 2:

$tile = new DiamondDecorator( new Plains() );

print $tile->getWealthFactor(); // 4

DiamondDecorator has a reference to a Plains object. It invokes getWealthFactor() before adding its own weighting of 2:

$tile = new PollutionDecorator(

new DiamondDecorator( new Plains() ));

print $tile->getWealthFactor(); // 0

PollutionDecorator has a reference to a DiamondDecorator object, which has its own Tile reference.

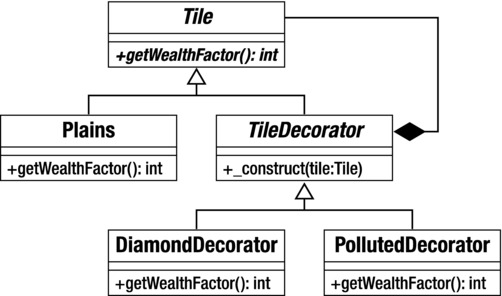

You can see the class diagram for this example in Figure 10-5.

Figure 10-5. The Decorator pattern

This model is very extensible. You can add new decorators and components very easily. With lots of decorators you can build very flexible structures at runtime. The component class, Plains in this case, can be significantly modified in very many ways without the need to build the totality of the modifications into the class hierarchy. In plain English, this means you can have a polluted Plains object that has diamonds without having to create a PollutedDiamondPlains object.

The Decorator pattern builds up pipelines that are very useful for creating filters. The java.io package makes great use of decorator classes. The client coder can combine decorator objects with core components to add filtering, buffering, compression, and so on to core methods like read(). My web request example can also be developed into a configurable pipeline. Here’s a simple implementation that uses the Decorator pattern:

class RequestHelper{}

abstract class ProcessRequest {

abstract function process( RequestHelper $req );

}

class MainProcess extends ProcessRequest {

function process( RequestHelper $req ) {

print __CLASS__.": doing something useful with request ";

}

}

abstract class DecorateProcess extends ProcessRequest {

protected $processrequest;

function __construct( ProcessRequest $pr ) {

$this->processrequest = $pr;

}

}

As before, we define an abstract superclass (ProcessRequest), a concrete component (MainProcess), and an abstract decorator (DecorateProcess). MainProcess::process() does nothing but report that it has been called. DecorateProcess stores a ProcessRequest object on behalf of its children. Here are some simple concrete decorator classes:

class LogRequest extends DecorateProcess {

function process( RequestHelper $req ) {

print __CLASS__.": logging request ";

$this->processrequest->process( $req );

}

}

class AuthenticateRequest extends DecorateProcess {

function process( RequestHelper $req ) {

print __CLASS__.": authenticating request ";

$this->processrequest->process( $req );

}

}

class StructureRequest extends DecorateProcess {

function process( RequestHelper $req ) {

print __CLASS__.": structuring request data ";

$this->processrequest->process( $req );

}

}

Each process() method outputs a message before calling the referenced ProcessRequest object’s own process() method. You can now combine objects instantiated from these classes at runtime to build filters that perform different actions on a request, and in different orders. Here’s some code to combine objects from all these concrete classes into a single filter:

$process = new AuthenticateRequest( new StructureRequest(

new LogRequest (

new MainProcess()

)));

$process->process( new RequestHelper() );

This code will give the following output:

AuthenticateRequest: authenticating request

StructureRequest: structuring request data

LogRequest: logging request

MainProcess: doing something useful with request

![]() Note This example is, in fact, also an instance of an enterprise pattern called Intercepting Filter. Intercepting Filter is described in Core J2EE Patterns.

Note This example is, in fact, also an instance of an enterprise pattern called Intercepting Filter. Intercepting Filter is described in Core J2EE Patterns.

Like the Composite pattern, Decorator can be confusing. It is important to remember that both composition and inheritance are coming into play at the same time. So LogRequest inherits its interface from ProcessRequest, but it is acting as a wrapper around another ProcessRequest object.

Because a decorator object forms a wrapper around a child object, it helps to keep the interface as sparse as possible. If you build a heavily featured base class, then decorators are forced to delegate to all public methods in their contained object. This can be done in the abstract decorator class but still introduces the kind of coupling that can lead to bugs.

Some programmers create decorators that do not share a common type with the objects they modify. As long as they fulfill the same interface as these objects, this strategy can work well. You get the benefit of being able to use the built-in interceptor methods to automate delegation (implementing __call() to catch calls to nonexistent methods and invoking the same method on the child object automatically). However, by doing this you also lose the safety afforded by class type checking. In our examples so far, client code can demand a Tile or a ProcessRequest object in its argument list and be certain of its interface, whether or not the object in question is heavily decorated.

The Facade Pattern

You may have had occasion to stitch third-party systems into your own projects in the past. Whether or not the code is object oriented, it will often be daunting, large, and complex. Your own code, too, may become a challenge to the client programmer who needs only to access a few features. The Facade pattern is a way of providing a simple, clear interface to complex systems.

The Problem

Systems tend to evolve large amounts of code that is really only useful within the system itself. Just as classes define clear public interfaces and hide their guts away from the rest of the world, so should well-designed systems. However, it is not always clear which parts of a system are designed to be used by client code and which are best hidden.

As you work with subsystems (like web forums or gallery applications), you may find yourself making calls deep into the logic of the code. If the subsystem code is subject to change over time, and your code interacts with it at many different points, you may find yourself with a serious maintenance problem as the subsystem evolves.

Similarly, when you build your own systems, it is a good idea to organize distinct parts into separate tiers. Typically, you may have a tier responsible for application logic, another for database interaction, another for presentation, and so on. You should aspire to keep these tiers as independent of one another as you can, so that a change in one area of your project will have minimal repercussions elsewhere. If code from one tier is tightly integrated into code from another, then this objective is hard to meet.

Here is some deliberately confusing procedural code that makes a song-and-dance routine of the simple process of getting log information from a file and turning it into object data:

function getProductFileLines( $file ) {

return file( $file );

}

function getProductObjectFromId( $id, $productname ) {

// some kind of database lookup

return new Product( $id, $productname );

}

function getNameFromLine( $line ) {

if ( preg_match( "/.*-(.*)sd+/", $line, $array ) ) {

return str_replace( '_',' ', $array[1] );

}

return '';

}

function getIDFromLine( $line ) {

if ( preg_match( "/^(d{1,3})-/", $line, $array ) ) {

return $array[1];

}

return -1;

}

class Product {

public $id;

public $name;

function __construct( $id, $name ) {

$this->id = $id;

$this->name = $name;

}

}

Let’s imagine that the internals of this code to be more complicated than they actually are, and that I am stuck with using it rather than rewriting it from scratch. In order to turn a file that contains lines like:

234-ladies_jumper 55

532-gents_hat 44

into an array of objects, I must call all of these functions (note that for the sake of brevity I don’t extract the final number, which represents a price):

$lines = getProductFileLines( 'test.txt' );

$objects = array();

foreach ( $lines as $line ) {

$id = getIDFromLine( $line );

$name = getNameFromLine( $line );

$objects[$id] = getProductObjectFromID( $id, $name );

}

If I call these functions directly like this throughout my project, my code will become tightly wound into the subsystem it is using. This could cause problems if the subsystem changes or if I decide to switch it out entirely. I really need to introduce a gateway between the system and the rest of our code.

Implementation

Here is a simple class that provides an interface to the procedural code you encountered in the previous section:

class ProductFacade {

private $products = array();

function __construct( $file ) {

$this->file = $file;

$this->compile();

}

private function compile() {

$lines = getProductFileLines( $this->file );

foreach ( $lines as $line ) {

$id = getIDFromLine( $line );

$name = getNameFromLine( $line );

$this->products[$id] = getProductObjectFromID( $id, $name );

}

}

function getProducts() {

return $this->products;

}

function getProduct( $id ) {

if ( isset( $this->products[$id] ) ) {

return $this->products[$id];

}

return null;

}

}

From the point of view of client code, now access to Product objects from a log file is much simplified:

$facade = new ProductFacade( 'test.txt' );

$facade->getProduct( 234 );

Consequences

A Facade is really a very simple concept. It is just a matter of creating a single point of entry for a tier or subsystem. This has a number of benefits. It helps to decouple distinct areas in a project from one another. It is useful and convenient for client coders to have access to simple methods that achieve clear ends. It reduces errors by focusing use of a subsystem in one place, so changes to the subsystem should cause failure in a predictable location. Errors are also minimized by Facade classes in complex subsystems where client code might otherwise use internal functions incorrectly.

Despite the simplicity of the Facade pattern, it is all too easy to forget to use it, especially if you are familiar with the subsystem you are working with. There is a balance to be struck, of course. On the one hand, the benefit of creating simple interfaces to complex systems should be clear. On the other hand, one could abstract systems with reckless abandon, and then abstract the abstractions. If you are making significant simplifications for the clear benefit of client code, and/or shielding it from systems that might change, then you are probably right to implement the Facade pattern.

Summary

In this chapter, I looked at a few of the ways that classes and objects can be organized in a system. In particular, I focused on the principle that composition can be used to engender flexibility where inheritance fails. In both the Composite and Decorator patterns, inheritance is used to promote composition and to define a common interface that provides guarantees for client code.

You also saw delegation used effectively in these patterns. Finally, I looked at the simple but powerful Facade pattern. Facade is one of those patterns that many people have been using for years without having a name to give it. Facade lets you provide a clean point of entry to a tier or subsystem. In PHP, the Facade pattern is also used to create object wrappers that encapsulate blocks of procedural code.