“Performance is the role an employee plays in the operation of a company. When an employee is not performing up to their full capabilities, something is adversely affecting performance. You need to work with the employee to determine what those obstacles are in order to transform an employee into a high performer” (Fracaro, 2015, p. 9).

From the employee perspective: “What does Aleta mean by saying I’m not performing?” Michael wondered. “I’m doing the job, aren’t I? As my supervisor, she gives me raises every year. What’s going on?”

From the manager perspective: “Michael is doing his job but his productivity rates are not going up,” Aleta said at the meeting with her CEO. “How am I supposed to measure performance? Is it different from productivity?”

What Is Performance, Really?

Performance produces productivity; so as an employee performs her job, she is creating value and productivity for the entire workgroup, department, and organization. Productivity is a measure of efficiency,1 that is, doing things right.2 However, performance involves both efficiency and effectiveness, that is both doing things right and doing the right things.2 It is possible for an employee to be working very hard but not contributing to the overall goals of the organization. Therefore, an employee can be productive without having effective performance, but both efficient and effective performances are essential to attaining goals.2

Understanding the nature of efficient and effective performance within a particular organization and department is part of the development of the Performance Leadership™ System. One size does not fit all! Performance Leadership is about holding people accountable for behaviors,3 not for their attitudes or intentions. There are two types of performance: contextual and task.4 Satisfactory work performance includes both task and contextual behaviors that directly or indirectly impact organizational and/or departmental goals. Contextual performance is often ignored by processes that are just performance evaluation systems,5 unlike the Performance Leadership System.

Contextual performance consists of behaviors that allow the work within the organization or department to flow smoothly.6 It is also called organizational citizenship behavior by some authors.7 Contextual performance involves both interpersonal facilitation, that is, the ability to work well and help others, and job dedication, which are behaviors that demonstrate commitment to the job.8 These two behaviors contributed heavily to a pleasant and smooth-running workplace. Specific contextual behaviors expected by the job holder should be a part of job requirements and performance measurement, such as demonstrating cooperation and showing up to work on time.

Measuring contextual performance involves both objective and subjective observation. As Mo Amani, one of the reviewers, suggested, the manager needs to tie contextual performance into the what and how. If a person is being helpful to others but ignoring his own work, then he is not displaying efficient and effective contextual performance, unless he is being helpful to others whose work is needed for his own work to be completed. (Yes, there is such a thing as being too helpful!) It is extremely difficult to find objective measurements for this dimension. Job dedication behaviors, such as showing up to work ready to perform, and interpersonal facilitation behaviors, such as cooperation, are important parts of positive workplace behavior—in keeping things moving smoothly and forward. Generally, the best workers display both appropriate contextual and task performance.

Task performance consists of three elements.9 The first is information that is used in the context of the tasks that the employee performs, called declarative knowledge. This knowledge is learned through education and/or experience and enables the individual to understand the task elements. The second is what the task is and how to perform it, or procedural knowledge. It includes cognitive, motor, interpersonal, and perceptual skills. The third factor is motivation. All three of the elements of task performance are required.10 A zero (0) for any one of the elements means that performance will equal zero (0). We call this a multiplicative effect.

Performance = Declarative Knowledge × Procedural Knowledge × Motivation

This multiplicative effect is important because:

• If a person has the knowledge required to do the job, but decides not to put forth any effort, then the sum of performance will be zero (0).

• On the other hand, if a person puts forth a great deal of effort, but has no knowledge (either or both types), then the sum of performance will also be zero (0).

The decision to demonstrate motivation involves three choices concerning effort10:

1. The decision whether to put forth an effort toward the task and how much effort to give;

2. The decision of direction of the effort; and

3. How long to persist giving the chosen level of effort in the selected direction.

The direction of motivation (effort) is critical. Managers are required to make sure that performances—both contextual and task performance—are directed toward the achievement of the departmental and organizational goals. This is why the position of supervisor or manager exists. Without direction, goals are not achieved. So motivation must be directed, not just expended, toward a goal. This is why an efficient and effective Performance Leadership System is critical—to achieve direction toward organizational and departmental goals.

Motivation is an internal process, and each employee’s motivation structure is unique to her or him. It is not something that the manager can control. Incentives are things that engage an employee’s motivation, and they may consist of such things as money or status, and also praise and internal satisfaction. However, no manager can motivate an employee. Although the terms incentives and motivation are often used interchangeably, motivation occurs within an individual and cannot be turned on and off by the manager. The manager can arrange incentives that make the employee want to engage motivation—which is the manager’s role in this process.

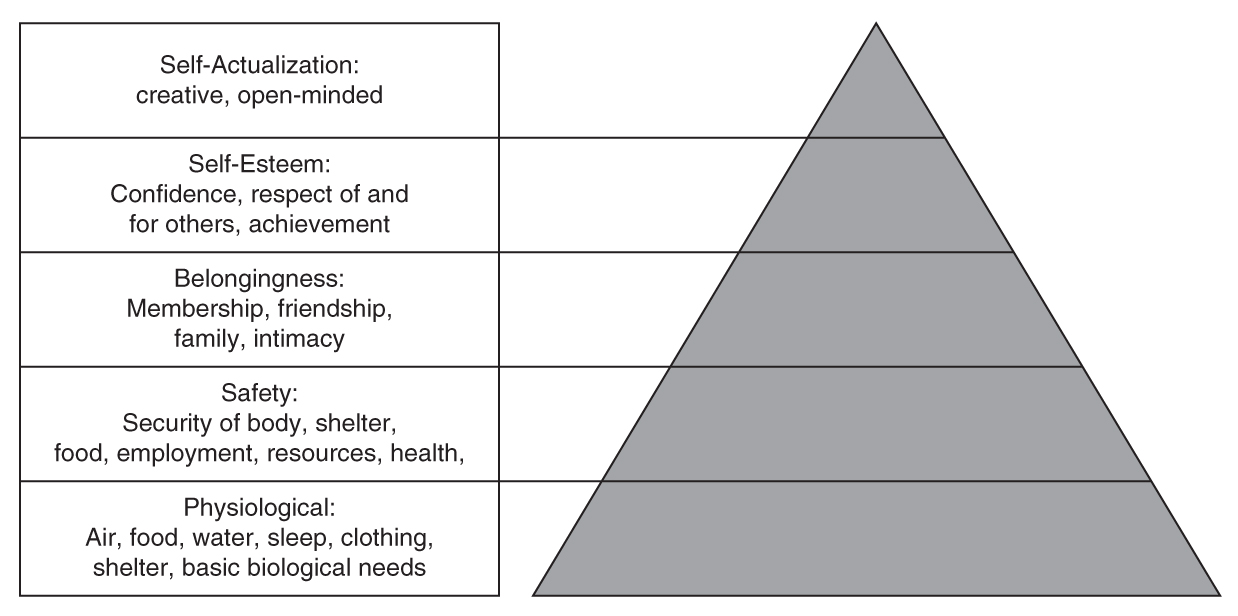

Maslow’s hierarchy11 identifies individual needs, with one type of need building on another, as shown in Exhibit 2.1. The first need is physiological, and the second need is safety. These needs are for air, water, food, shelter, clothing, a safe environment, and other basic needs of life. Employees who are unable to make ends meet with their wages (such as minimum wage earners) have not satisfied these basic needs. Until these needs are met, individuals generally cannot progress toward satisfying the other three needs. This is why it is not possible to interest workers in commitment, development, or innovation until they have achieved the security of these two basic needs.

The next need is for love, belongingness, or social exchange—all of these words have been used to describe the need to be accepted by other people. In satisfying this need, an employee forms networks and develops commitment to his peers, supervisors and managers, and the organization itself. The fourth need is for esteem (or self-esteem), which is when an individual believes that (a) the work is worthwhile, (b) performing the work well is possible, and (c) others respect her. While satisfying this need, employees develop skills, knowledge, and abilities and use them to learn new things. Self-actualization is the highest need; satisfying this need requires the chance to be creative and innovative. For most people, each step must be satisfied before moving to the next one.

Taking Maslow’s hierarchy of needs11 (Exhibit 2.1) into account, we can see why money and monetary incentives do not always motivate. Having work that matters can create high motivation in most employees. If a person is not being paid a living wage, then he will not have the capacity to be committed to the employment. However, if a person is paid enough to satisfy the first two levels of Maslow’s hierarchy, she will look for other motivating factors. Pink12 discussed four decades of research dealing with the different reasons that people engage their own motivation. In his book, Drive: The Surprising Truth about What Motivates Us, the surprise to most is that humans seem to be more highly motivated by the need to achieve esteem and self-actualization than money. His TED.com talk discusses this research and is well worth viewing.12

Exhibit 2.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Source: Adapted from work by Maslow (1943, 1954, 1968).

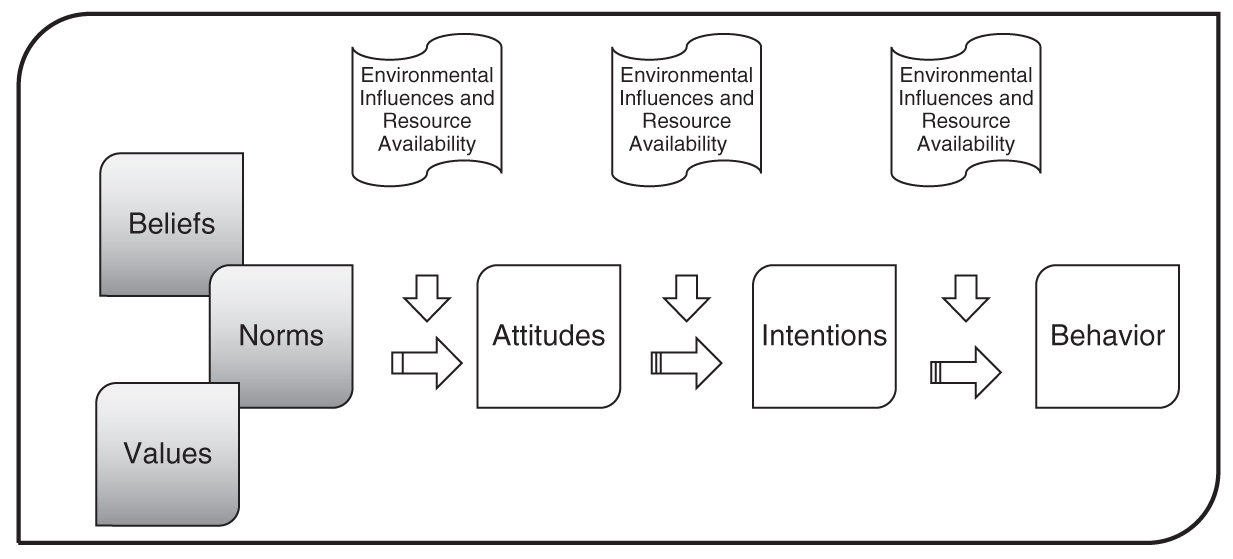

Exhibit 2.2 outlines the processes leading to performance, which is adapted from Ajzen’s work.13 As the authors point out, attitude and intention cannot be well measured, because they are totally internal processes. In the end, managers can only measure behavior. In addition, environmental influences affect the outcome of each phase of the process.14

Exhibit 2.2 Pathway to Behavior

Source: Adapted from The Theory of Reasoned Action/Planned Behavior research stream (http://people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.diag.html).

The value of the Pathway to Behavior (Exhibit 2.2) is that it can be used to diagnose behavioral problems. When behavior is a problem, then the manager can search with the employee along the chain to see where there are environmental and resource constraints that inhibit appropriate behavior. This is not to say that all behavioral problems can be corrected in this manner, but it is a helpful model to understand them. In some cases, managers can relieve the environmental and resource constraints that hamper the employee. When the constraints lie within the employee’s private life, the manager should identify them and allow the employee to correct them (or not). Some organizations offer Employee Assistance Programs (EAP), which can be helpful for the employee to deal with personal constraints.

For example, a person may have the intention of showing up on time for work, but a flat tire (environmental influence) between intention and behavior makes him late. Another person might want to do a good job, but knows that there is very little time to complete the task (resource availability). Therefore, she might not intend to complete the task as well as she could because of the time constraint (resource availability) existing between attitude and intention. In other cases, addictions, family difficulties, or other personal issues may reduce performance, making them environmental influences that the employee must correct.

Incentives, therefore, must take into account each employee’s place on Maslow’s hierarchy11 (Exhibit 2.1), as well as the pathway to behavior (Exhibit 2.2). The only way to know what motivates employees is by knowing each subordinate well. For example, if the manager is aiming for subordinates that are committed to the organization and department, she must pay a wage sufficient to allow the employ to move to the belongingness stage of Maslow’s hierarchy. She must also actively create a congenial workplace, develop employees, and craft opportunities for creativity and innovation.

When employees can reach the level of belongingness, organizational commitment can be internally activated. Development, by the individual and/or the organization, can be undertaken only when the employee reaches the self-esteem level of Maslow’s hierarchy, while creativity and problem solving require the self-actualization level.

The process of motivation is highly dependent upon a person’s status on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.11 Knowing where the employee’s needs are located, managers can focus on appropriate incentives, rather than on the fruitless task of trying to motivate someone. Applying the incorrect incentive to a particular employee may reduce their motivation instead of strengthening it.15

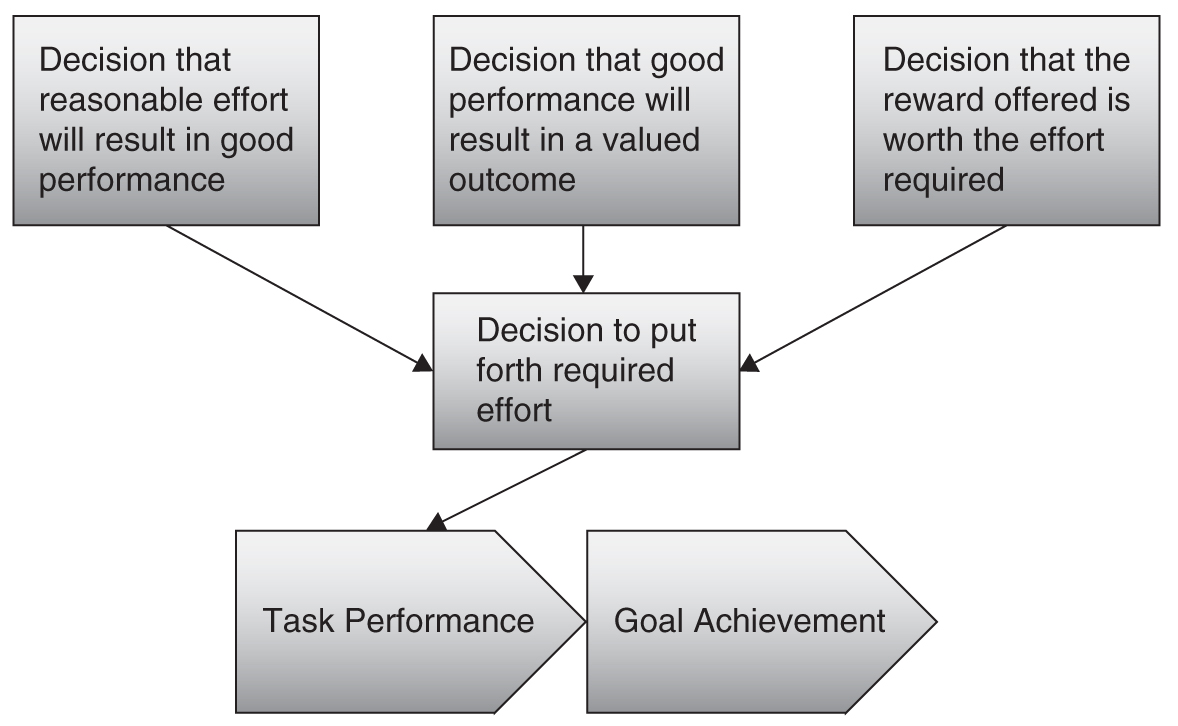

The incentive that one person desires may not be valued by another, even among those who are committed and self-actualized. In looking at Maslow’s theory in Exhibit 2.1, we can understand that the person at the lower levels might view money as an adequate incentive, but those with enough money may need something different. It strongly depends on the nature of the task12 and is probably explained by Expectancy Theory,16 shown in Exhibit 2.3, which includes consideration by the employee of whether:

• He believes that he can perform the task well with a reasonable amount of effort,

• There is a reward that he values, and

• There is a likelihood that he will receive the reward for performance.

Exhibit 2.3 Expectancy Theory

Source: Adapted from Vroom, 1964.

Once a person engages motivation and has the procedural and declarative knowledge needed to perform the task, we generally see high performance. However, it is essential to take note of the things that can interfere with each individual’s performance. Environmental influences, such as room temperature, or lack of resources, such as time or equipment, can derail even the most motivated worker.

Example 2.1

The clock chimed 9 a.m. as Peter walked into the door, making a beeline for his office. Alejandro felt that his authority as supervisor of the area was being undermined when people didn’t show up at the appointed start time of 8 a.m.

“But how do I deal with the problem?” Alejandro wondered. “Peter is almost never late, but it is really close to performance appraisal time, and I don’t have anything to write negative about him. The manager will kick it back if I show a perfect score. This is a great opportunity to have something negative to say.”

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

To explain constraints versus intention, the concept of being punctual is useful. If an employee is always on time but, one day, is late by an hour, the manager may see the one example as bad behavior, particularly if it is close to performance appraisal time. However, the intention to be on time was there for the employee—but there was an accident on the freeway. How is the supervisor going to evaluate this one instance of poor behavior?

The supervisor also has constraints. Without the Performance Leadership System in place, he must catch Peter doing something right or wrong because he must do an acceptable, and often average, evaluation at the end of the year. Alejandro is right about his own manager: Many organizations do not believe that they have any employees that deserve a five out of five on an evaluation rating. But, how can you have a top (five out of five) organization if all of your people rate three out of five on a performance scale?

Nicole noticed that Aaron was not keeping up with the cleaning regimen that was required in the work area. As manager, Nicole was judged on how well the area was maintained, and the Department of Health could come in at any time. In its current state, there was no way that they would pass inspection. He decided to talk with Aaron. After all, Dita, his colleague, was able to keep up with the tasks, so it was possible to complete them within the shift. He called Aaron into his office.

“Aaron,” Nicole began, “I don’t understand why you are not able to complete the cleaning tasks. Dita is able to do it on her shift. Why can’t you? Don’t you have any commitment to this organization? Don’t you care if we get a bad rating from the Department of Health?”

Aaron looked at Nicole in amazement. “I am working as hard as I can,” he thought. But he often had to call to check on the children at home. Without the money to hire a babysitter, there were constant worries about leaving the 15-year-old boy in charge of his two sisters, aged 8 and 11. Since his wife died, there was only one income to support the four of them, and they all often went without lunch so that they might have something for dinner. Living on his minimum wage was a challenge, and the 15-year-old boy had to drop out of afterschool activities and reduce his time on studies to take care of his siblings. That lost time might have gained him a scholarship. Aaron thought, “I hate that the worst. He will end up being like me—a low wage earner without a future.”

Dita, on the other hand, was the second wage earner in her family, and only had one daughter in high school. Dita often told him that she was working to gain extra money to send her daughter to college, money that was needed even though there was a scholarship for her daughter’s good grades. “Doesn’t Nicole understand?” Aaron thought.

What Is the Problem Here? How Can Performance Leadership Help in this Situation?

Nicole must realize that talk of commitment to the organization will not help in Aaron’s situation. Those making minimum wage are most often at the point of mere subsistence. They live with the immediate threat of being without food, clothing, education, and/or housing. With these worries on his mind, Aaron is unable to make a deep commitment to the organization. He is consumed with worries about existing from day to day.

One Performance Leadership System solution would be to remind Aaron of his responsibilities to the organization and the restrictions regarding phone use at work. It seems unkind, but these rules need to be enforced—if there is a need to have them at all. Otherwise, managers are wasting their time making rules that they don’t or won’t enforce.

A better Performance Leadership System solution would be to look at the way that the entire area is organized and tasks are distributed. If the system had been in place, the drop in productivity would have been evident to Nicole when it initially began. She could have started conversations with Aaron to identify constraints within the job that is keeping him from his best performance. Is it possible to share the workload better, allowing an increase in Aaron’s wages as he takes on more responsibility?

Aaron seems to be able to follow instructions, since he has been in the organization for 4 years. Is there a reason that he is not being moved up to higher paying jobs? In jobs paying minimum wages, turnover is usually high at the front line and supervisory levels, so there should be room to move him up. This would involve coaching and developmental sessions, with an eye to improving his situation.

Nicole’s comparisons of Aaron to Dita might be unrealistic. Dita’s shift might be when the workload is lighter, making the cleanup easier. Dita obviously has a different aim and is on a different level of Maslow’s hierarchy, and Nicole should recognize that her wages are not needed to support the family but are used to improve her daughter’s future. Dita is likely more committed to the organization since she does not have to constantly worry about the bare necessities of life.

One solution that must be considered is to fire Aaron for poor performance. This is not the suggested solution, but it is one that should be considered if it is not possible to resolve the situation. The goals must be achieved, and ignoring the situation will not help. However, the manager must be sure that hiring another person to take Aaron’s place will result in satisfactory performance. If there are environmental constraints that prevent Aaron from achieving high performance, then others are unlikely to be successful.

Notes

1. Daraio & Simar, 2007.

2. Drucker, 1967/2006.

3. Bernardin, Orban, & Carlyle, 1981.

4. Motowidlo, Borman, & Schmit, 1997; Motowidlo & Van Scotter, 1994.

5. Kane & Lawler, 1979.

6. Borman, Penner, Allen, & Motowidlo, 2001.

7. Borman, 2004.

8. Borman, 2004; Van Scotter & Motowidlo, 1996; Van Scotter, Motowidlo, & Cross, 2000.

9. See for example, Campbell, 1990; Griffin, Neal, & Neale, 2000.

10. Pritchard, 1976.

11. Maslow, 1943, 1954, 1968.

12. Pink, 2011; TED Talk at http://www.ted.com/talks/dan_pink_on_motivation

13. Ajzen’s work (2006) found at http://people.umass.edu/aizen/tpb.diag.html

14. Ajzen, 1991; Ajzen & Fishbein, 2008; DeCotiis & Petit, 1978; Dunnette & Borman, 1979; Kane & Lawler, 1979; Jacobs, Kafry, & Zedeck, 1980; Landy & Farr, 1983.

15. See for example, Burroughs, Dahl, Moreau, Chattopadhyay, & Gorn, 2011; Ims, Pedersen, & Zsolnai, 2014; Pink, 2011.

16. Vroom, 1964.