1

Traditional Valuation Methods and Ways of Applying Them

1.1. Introduction

It is imperative that the investments of a business generate a sufficient level of profitability to satisfy the demands held by the investors. If the obtained (or predicted) level of profitability is higher than the level of profitability that is expected given the risk, the value of the economic asset increases, impacting the value of shares in an upward fashion1. Otherwise, the investor will not be satisfied with the profitability of their investment in relation to the risk absorbed to sell their security. Enterprise and share value thus will fluctuate in a downwards fashion. And so, the direct consequence of the investment policy is a variation in economic value of equity, i.e. the market capitalization if the company is listed2. It thus follows that an investor’s power lies, on the one hand, in their decision to allocate funds to the company (without financial backing, the company is no more) and, on the other hand, in the evaluation of the economic asset through securities that have already been issued3. Consequently, changes in the value of economic assets are reflected almost entirely on market capitalization. When the company faces significant difficulties, the role of creditors changes because from a financial perspective, they then own the company. When the equity value is almost zero, adjustments can only be made through the net debt, whose value becomes lower than the nominal value. Therefore, liabilities are the screen placed between the value of economic assets and the financial decisions taken by investors.

Just as the investment policy is able to create or destroy value, the financial policy through the financial structure can theoretically change the value of equity. It is not so much of question of increasing the free cash flow of economic assets as it is of reducing the weighted average cost of capital, synonymous with the financial cost of the company, i.e. the minimum rate of return that assets must generate. In this way, it seems pertinent to interrogate whether an optimal liability structure can be created. The said structure would enable the cost of capital to be minimized, thereby maximizing the enterprise value.

To guide their decisions to allocate their resources to companies, investors use traditional valuation methods. In this way, the economic valuation of shareholder equity can be obtained by relying on a stock market analysis by comparing the aggregate multiples of the balance sheet and/or the income statement, or by undertaking a transactional comparison of the processes being carried out in the sector that the company to be valued operates in. Furthermore, by producing a business plan, i.e. by providing free cash flows that are discounted at the cost of capital, the investors may estimate the value of the company based on its future plans. Finally, by adopting a proprietary approach, investors are able to concentrate on the real assets held at a given time by the company. These three approaches are in theory supposed to be combined in order to refine the valuation further. With this in mind, it becomes ever more important to investigate whether an optimal capital structure really exists. Indeed, when it comes to carrying out a valuation by discounting free cash flows, two possibilities arise in terms of maximizing the enterprise value. Either the investment policy is relevant in itself, as it generates significant cash flows which lie in the numerator of the formula, or it is possible to consider that an adequate financial policy is carried out on condition that it decreases the cost of capital, which is at the denominator of the formula. In both of these scenarios, the enterprise value is increased.

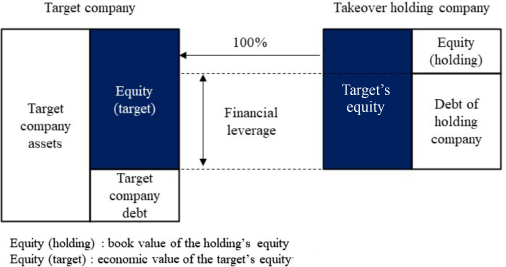

Auditing activities come in particular from this type of valuation exercise. Theories from organizations, which help to explain the levels of corporate debts, go beyond outlining how to adopt acquisition strategies. Indeed, the very nature of shareholding encourages one to implement different types of financial arrangement that influence both the evolution of the power of holders of capital and the choice of which financial structure to adopt in order to acquire the target company.

1.2. The cost of financial structure

The portfolio theory from Markovitz (1959) deals with determining the cost of equity. The investor’s profitability demand depends on their degree of risk aversion. The portfolio to be chosen is graphically located at the intersection of the efficient frontier and one of the curves that characterizes the investor’s iso-utility. Sharpe (1963) simplifies this theory by assuming that the expected return on an asset is linked to the return on a market index. Thus, the investor’s demand for profitability depends solely on systematic risk. Efficient diversification of an asset portfolio eliminates the specific risk of the share.

An economic reading of a balance sheet consists of identifying, at a given moment, all the jobs involved in the company’s operating cycle and the origin of its resources. Economic assets (or enterprise value) are the sum of fixed assets and working capital requirements, i.e. all of the network in progress that is aligned with the operating and investment cycle4. Economic assets are financed by equity and net debt. And so, the market value of the economic asset is divided between the market value of these two types of resources. This results in a balance sheet of the company that only includes market values. In this context, the question arises as to whether there is an optimal capital structure that maximizes enterprise value and thereby minimizes the cost of capital.

The traditional approach, wherein evaluation is carried out without taxation, ensures that there is an optimal liability structure resulting from a sound use of the leverage effect. By also considering a tax-free approach, equilibrium market theory asserts, on the contrary, that there is no optimal capital structure because investors are able to duplicate at their level the financial operations of companies without cost and without any additional risk. The arbitrations that they can mobilize in the event of initial situations where the financial structures would be different lead to a rebalancing of the market. That is to say, they help to ensure that the value of the financial liabilities of two companies that are equal in every aspect becomes equal again. In the presence of taxation, the value of an indebted company is equal to that of a company that is not indebted, to which we must add to the present value of the tax savings linked to the tax deductibility of interest charges. However, even in the presence of taxation, the theories presented by organizations teach us that the choice of whether or not to go into debt comes more from the agent conflicts between the different parties such as shareholders and creditors, or from signals sent to the market more than from intrinsic costs.

1.2.1. Financial asset valuation

The models for valuating financial assets or the capital assets pricing model (CAPM) is used to evaluate the equity of a company in a balanced market. This formula provides an estimate of the rate of return expected by the market for a financial asset according to its systematic risk.

Markowitz (1959) states that between two portfolios characterized by their supposedly random return, one would retain, at identical risk, the company with the highest expected return and, with the same expected return, the company with the lower risk. This principle means that a number of portfolios may be dismissed, as they are less efficient than others. The efficient frontier represents the curve that connects the set of efficient portfolios. The portfolios that sit below this curve are rejected.

Consequently, it is possible to determine the weight of two assets that appear in a portfolio in order to minimize the risk thereof:

or:

- – Rp: portfolio return;

- – xi: weight of asset i in the portfolio.

Variance is minimal when its derivative is zero. We then look for xA such that:

As a result:

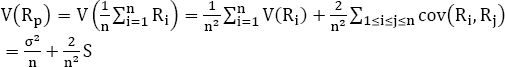

Now considering Rp, the portfolio return made up of n assets characterized by their respective return R1..., Rn, we have:

In order to determine E(Rp) and V(Rp), we suppose that:

Assume first that the returns of each of the n assets fluctuate independently of each other. In this case, the variance of a sum is equal to the sum of its variances. And so:

If n approaches infinity, then ![]() goes to 0.

goes to 0.

We then suppose that the performance of each of the n assets is correlated with each other. In this case:

where:

Let ![]() be the average covariance of portfolio P. By definition:

be the average covariance of portfolio P. By definition:

where N corresponds to the number of covariances.

In total, the number N of terms is equal to 0 + 1 + ... + (n – 1), so:

Like:

One has:

Consequently:

When n approaches infinity, ![]() approaches 0 and

approaches 0 and ![]() approaches the ratio of terms of higher degree. This ratio is equal to 1. By multiplying this result by

approaches the ratio of terms of higher degree. This ratio is equal to 1. By multiplying this result by ![]() , we may deduce that V(Rp) approaches the mean covariance

, we may deduce that V(Rp) approaches the mean covariance ![]() The risk equal to the standard deviation of Rp cannot therefore be eliminated, even by diversifying the portfolio insofar as it therefore approaches the square root of the mean covariance.

The risk equal to the standard deviation of Rp cannot therefore be eliminated, even by diversifying the portfolio insofar as it therefore approaches the square root of the mean covariance.

On the graph, this means that the curve that represents the risk as a function of the number of securities that are contained within the portfolio admits a horizontal asymptote of equation ![]() .

.

The basis of the CAPM comes from the hypothesis within the Markowitz model, i.e. a portfolio for which performance Rp is defined as:

We assume moreover that the performance Ri of each asset i is linearly related to a market index denoted I. In other words, ![]() , where I and

, where I and ![]() are a random variable that presents the following properties:

are a random variable that presents the following properties:

- –

- –

constant;

constant; - –

for 2 assets i and j becoming part of the portfolio.

for 2 assets i and j becoming part of the portfolio.

In this case, the choice of portfolio located on the efficient frontier which should be retained according to the degree of the investor’s risk aversion is simpler. It comes from solving a system of equations that correspond to the inversion of an almost diagonal matrix (it is then necessary to consider the inverses of the numbers located on the diagonal). The financial asset equilibrium model, from which the formula for the capital market line (used to determine the cost of equity) is derived, makes the simplified hypothesis model from Sharpe (1963) endogenous. In other words, this method consists of replacing the index I from the Sharpe formula with the performance RM of the whole market.

The formula is thus:

When looking at a portfolio P composed of n assets i each of them entering for a proportion Xi, the portfolio yield is as follows:

We can thus calculate:

And then:

As a result, the beta of a portfolio is the weighted average of the betas of the assets that make it up.

Let us consider a portfolio composed of a market index contract and non-risky securities. For example:

- – XM: proportion of market index contracts in the portfolio;

- – βM: beta of market index contracts;

- – βF: beta of non-risky securities;

- – RF: risk-free rate.

Based on the weighted beta formula, the beta for this portfolio is:

As βM is the beta of market index contracts, βM = 1.

And βF is the beta of non-risky securities, βp = 0.

So:

Since:

We can deduce that:

By setting p = I, i.e. a portfolio reduced to asset i:

where:

– Ri: share return i;

– Rm: market yield;

– βi: systematic risk of company share i;

– Rf: risk-free rate;

– Rm – Rf: market risk premium.

Systematic asset risk represents the coefficient of volatility of the stock, relative to the market. If βi is greater than 1, the share is said to be aggressive and the variations in market yield are increased at the level of the return of the share. If βi is less than 1, the share is said to be defensive and the variations in market yield are reduced at the share level. Finally, if βi is equal to 1, the share replicates the market.

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC), denoted K, is the average annual rate of return that a company’s assets must generate. It is the minimum rate required by the shareholders and creditors of the company to agree to finance its investments and projects. K is the weighted average of equity and net debt. The weighting is a function of their weight within the value of the economic asset. To be noted:

– kD: rate of return required by creditors after tax;

– kCP: rate of return required by shareholders (previously, Ri);

– VD: market value of net debt;

– VCP: market value of equity

Economic assets are financed by equity and net debt. Market value is split between that of net debt and that of equity. The question then is where there is an optimal capital structure that minimizes the cost of capital. In other words, it seems evident that the enterprise value increases with a sound investment policy because it generates, in this case, significant cash flow. What is more, since the balance sheet is in equilibrium, can we say that it is reasonable to consider that an optimal financial policy (one that results from a perfect distribution between equity and debt) can maximize this same enterprise value, due to minimizing the cost of capital?

1.2.2. Optimal capital structure

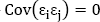

According to the traditional approach, in the absence of taxation, both for the company (absence of corporate tax) and for the investor (absence of income tax and capital gains tax), there is an optimal liability structure that maximizes the value of the economic asset and therefore minimizes the cost of capital through the measured use of debt and its leverage effect.

The company value is a product of discounting the cash flow that is available at rate K. Since debt is less risky, it is less expensive than equity. Thus, any moderate increase in debt decreases the WACC to the extent that a cheaper resource (debt) is substituted for a more expensive resource (equity). Having said this, any increase in debt in the weight of financing increases the risk of the shareholder passing it on to the cost of equity, which will cancel part of the decrease in total financial cost. In addition, at a certain level of debt owed, the cost also increases due to the increase of risk. The operation can be repeated until the requirement for the rate of return on equity is so high that it cancels out the positive effect of additional debt. At this level of financial leverage, the company has reached its optimal capital structure, as it has the lowest possible WACC (or cost of funding) and therefore the highest economic asset value.

Figure 1.1. Optimal weighted average cost of capital according to the traditional approach

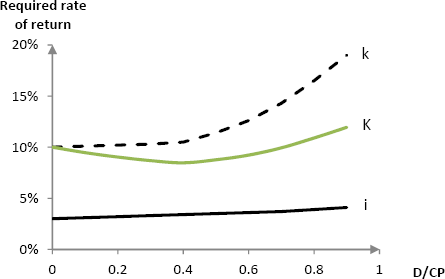

According to the theory of market equilibrium, in the absence of taxation, the enterprise value of two identical companies with different financial structures is the same. This is because investors can reproduce financial transactions at their level without additional cost and risk. In other words, when undertaking a valuation of the company, they are indifferent to any financial construction. Modigliani and Miller (1958) affirm that arbitrations made by investors imply that there cannot be an ideal liability structure in a market that is in equilibrium.

When i increases, the rhythm at which k progresses will slow down, such that K remains constant: stakeholders are relieved of part of the risk of the company that is passed on to the creditors as soon as the amount of debt becomes significant. In a market in equilibrium, the increase in expected profitability linked to the leverage effect and the increase in risk offset each other so that the value of the share remains the same. The increase in the level of debt that a company has increases the risk of the shareholder as well as the profitability that they require. This is so that ultimately the wealth of shareholders does not change. The value of debt comes down to the exact price that has to be paid for equity. In other words, one should not pay the company twice by buying the shares at the cost of the economic asset and then paying off the debts. Asset value is the same whether it is financed by debt, equity or both. The weighted average cost of capital of the company is independent of its two sources of financing. Debt and equity will adjust according to any change in financial structure. Indeed, increasing debt does not make the cost of capital decrease. On the contrary, debt increases the risk for shareholders and therefore the rate of return that they demand. The weighted average cost of capital is constant regardless of the financial structure.

From a mathematical perspective, the cost of capital of a company (independent of its financial structure) corresponds with the capitalization rate p of the expected operating profit of a company without debt and belonging to the same industrial risk class5. In other words, this leads us to consider that the enterprise value is akin to a perpetual growth rate of constant future operating results discounted at the rate ρ:

The cost of equity k corresponds to the financial profitability rf insofar as we can reason it ad infinitum. From there:

This theory does not explain the everyday reality for two key reasons. On the one hand, by conserving the same market logic, biases start to emerge. They explain why a business goes into debt and why it does not go beyond a certain threshold. The fundamental parameters are taxation and the costs of bankruptcy associated with excessive debt. On the other hand, there are interferences between the financial structure and the investment which can be explained above all by the divergent interests of different financial partners in terms of value creation and by the divergent personal situations in terms of access to certain information.

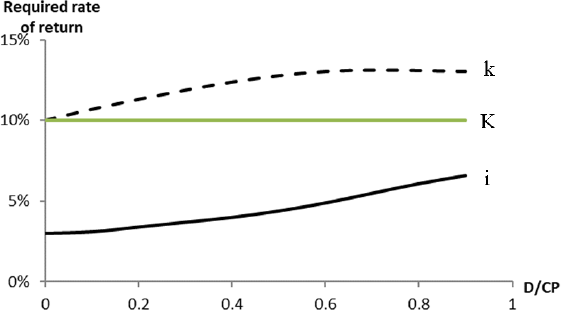

Modigliani and Miller (1963) perfected their theory by taking into account corporate tax. When we consider corporate tax, the result is that debt is favored over equity. In fact, financial expenses are deductible from the tax base on companies. The company’s creditors collect them without having already been taxed. However, dividends are not deductible. The shareholders receive them after tax payment. In a sense, deducted financial expenses can be seen as a state subsidy to the indebted company. So that they can benefit, it is enough for the expenses to be taxable, i.e. it is a beneficiary. If the company uses debt on a permanent basis, it will benefit from a tax economy that is considered at the level of the value of its economic asset:

where:

- – X: renumeration of capital providers to the indebted company;

- – X*: renumeration of capital providers to the company without debt;

- – VE: value of the assets of an indebted company;

- – VE*: value of the assets of a company without debt;

- – i: cost of debt;

- - ρ: cost of the capital of a company without debt;

- – VD: market value of debt;

- – VCP: market value of equity;

- – EBIT: operating result;

- – τ: corporate tax rate;

- – iVD: financial expenses;

- – iVDτ: tax reduction generated by the deductibility of financial expenses;

- – shareholders receive all of the corporate profits.

If we consider that the value of the assets corresponds to a perpetual annuity of future flows, then the flows of the company with no debt are discounted at the rate ρ, i.e. ![]() and the tax reduction if discounted at the cost of debt. Moreover:

and the tax reduction if discounted at the cost of debt. Moreover:

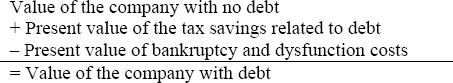

In the case of corporate tax, the value of the economic assets of a company with debt is equal to the value of the economic assets of a company without debt, increased by the present value of the related tax savings. This saving will only be effective if the profitability of the company is sufficient and it does not benefit from other exemptions (tax loss carryforwards, research tax credit, etc.). This is the basis of the APV method (adjusted present value), which separately recommends valuing economic assets by discounting cash flow and the value of the tax savings generated by financial expenses. The question then is to know the discount rate of the tax savings due to the tax deductibility of financial expenses. Modigliani and Miller advocate discounting the tax savings to the cost of debt.

This method is appropriate if one thinks that these tax savings are certain. Therefore, the value of the tax savings is equal to the value of the debt multiplied by the tax rate. On the other hand, it is commendable to think that the company will not be forever in debt, being the receiving party and taxed at the same rate. In this way, it is quite conceivable to discount the tax savings to the cost of equity, especially since it goes to the shareholder.

As a result, the adjusted cost of capital is first obtained by determining the cost of equity:

Recalling that the enterprise value VE* corresponds to a perpetual annuity of operating results (constant in the future) discounted at ρ or at the enterprise value VE minus the tax savings linked to the debt, we have:

And so, the cost of capital K equals:

The cost of capital thus is not affected by an increase in the cost of debt because the formula for the adjusted cost of capital does not contain i. In addition, Modigliani and Miller’s formula for the cost of capital expresses that an increase in the cost of debt i leads to a decrease in the cost of equity k.

The increase in debt burden in finance can be translated into a fall in the cost of capital. Therefore, the increase in debt burden results in an increase in enterprise value. The difference between the enterprise value of the company in debt and the enterprise value of the company not in debt corresponds to the value of the tax-saving perpetual annuity generated by the tax deductibility of financial expenses. In other words, the increase in debt only has the effect of increasing the value of tax credit (the change in the financial structure, as it has no impact on the value of industrial assets).

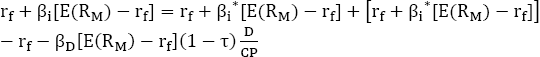

Hamada (1972) is influenced by the work of Modigliani and Miller when defining the equation of unlevered beta of a share. Starting from the cost of equity:

The CAPM equation is used, while assuming that the company is in debt at the risk-free rate (in this case i = rf):

Assuming the firm is in debt above the risk-free rate, CAPM is applied to the debt using the βD debt beta:

However, the costs of bankruptcy are the first limitation to this reasoning. Indeed, a company that has recurrent debt runs the risk of no longer being able to meet its commitments. If this is the case, the company files for bankruptcy, which theoretically qualifies as a reallocation of assets for productivity purposes. For an investor with a perfectly diversified portfolio, bankruptcy is seen as a mechanism for reallocating resources. The cost is therefore zero. However, in practice, markets do not work perfectly. Bankruptcy has a real cost because of its very nature. The decrease in enterprise value resulting from the inclusion of the costs of bankruptcy has been studied in particular by Molina (2005), Almeida (2007) and Bae (2011). The judicial liquidation of a company generates:

– direct costs: severance pay, attorney fees, legal costs, shareholder efforts to obtain a liquidation bonus, etc.;

– indirect costs: canceled orders (for fear that they won’t be honored), reduction in supplier credits (for fear of never being paid back), impact on productivity (strikes), inability to obtain funding, etc.

From this perspective, the bankruptcy of a company can be perceived as the refusal of shareholders to offer additional funds. They consider their previous bets to be lost. Shareholders effectively hand the company over to its creditors who thus become the new stakeholders. Creditors bear the full cost of the company’s demise, which further reduces the possibility of debts being paid back. Even though they don’t go as far as bankruptcy, the company with great debt faces the costs of dysfunction which penalize its value: a reduction of the cost of research and development, maintenance, training or marketing (in order to meet the debt deadlines), difficulty in finding new resources to finance profitable projects, demotivation of some of the staff members, etc.

Due to tax deductibility, tax can create value. A business with debt may be worth more than a business with no debt. This point cannot be overstated for two main reasons. On the one hand, in times of crisis, excessive debt leads tax advantage to disappear (the company does not make enough profits). On the other hand, it can make dysfunction and bankruptcy costs emerge. The value of a company with debt can thus be broken down as follows:

The above reasoning can also be broken down in terms of the weighted average cost of capital. That is to say, when the company goes into debt, the cost of capital will be reduced thanks to the tax savings on interest. But when the company approaches bankruptcy, the costs of bankruptcy are factored into the rate of return demanded by investors. Paradoxically, we can uncover the traditional theory which advocates controlled debt. The optimal theoretical debt ratio is achieved when the present value of the tax savings due to additional debt is just offset by the increase in the present value of bankruptcy and dysfunction costs.

Investor taxation is the second limit to the reasoning. Miller (1977) echoes the 1958 conclusions from Modigliani concerning the lack of an optimal financial structure. In his theory, taxation is taken into account both at the level of the company and at the level of the investor. Miller argues that the effect of income tax cancels out that of corporate taxes so that the value of an economic asset is the same, regardless of the liability structure that finances it. The author observes that in general, investors are taxed more personally on debt income than on equity income. In other words, the tax advantage of debt at the corporate level is thwarted by the tax advantage of equity at the investor level. There is therefore no one source of funding that prevails over another:

and:

and:

where:

- – rf: risk-free rate;

- – ts: corporate tax rate;

- – ta: tax rate (legal persons) on the remuneration of shares;

- – to: tax rate (legal persons) on the renumeration of bonds.

The value of assets corresponds to a perpetual annuity of future cash flows. Therefore, the flows of the company without debt are discounted at the rate ρ and the flows generated by the debt are discounted at the risk-free rate rf. So:

Let VD’ be the capitalized value of debt for lenders:

And let G’ be the possible gain due to debt:

Therefore, if (1- to) = (1- ts) (1- ta), then G’= 0.

Factoring in investor income tax can reduce the debt benefit. Ultimately, it should be kept in mind that from this set of controversies, taxation is an essential parameter in absolute terms, but that it is unlikely that it serves to fully explain the financial structure of companies. What is more, the cost of debt per se may not be sufficient to explain a business’s choice as to whether or not to take out a loan. Indeed, the theory of markets in equilibrium starts from the affirmation that the company is a single player. Therefore, it ignores any conflicts that may arise between different stakeholders within the company as they may pursue different or even opposing goals. In this context, taking out debt can be seen more as a signal, beyond the financial considerations that are implied.

1.2.3. Theories of organizations

Signaling theory maintains that company executives have more information than funders and are better able to forecast future cash flows of the business. Thus, any signal emitted to show that flows are better than expected or that the risk is lower than expected enables the creation of value for the investor. In order for the signal to be credible, it must have its own sanction if it is proved to be wrong. Debt is seen as an indicator of the good health of a company since the manager of an underperforming company cannot go into debt. It reflects the manager’s desire to improve the financial performance of their company in order to generate the cash flows necessary to service the new debt. Synonymous with a market that bears good news, the loan generates a rise in stock prices. Ross (1977), Blazenko (1987), John (1987) and Narayanan (1988) have notably studied the role of debt as a signal given to the market on the financial health of companies. Indeed, the managers of a company whose debt is increasing signal to the market that they know the company’s status, that it is favorable and that the performance of the company will by consequence allow them to pay additional financial charges and repay this new debt without difficulty. And so, perhaps a signal does not tell us about the financial structure of a company, but rather its ability to transform. On the other hand, announcing an increase in capital leads to a drop in the share price. Indeed, directors do not carry out capital increases when the value appears to them to be undervalued (so as to not place their current shareholders in an unfavorable situation). If there is an unjustified increase in capital, the investor will deduce that the stock price is overvalued and that is why the current shareholders accept the emergence of shares. It is therefore evident that if a director sells their stake in a company, it is a negative signal. This means that they have internal information; that the value of future cash flows, taking into account the risk, is lower than the price at which they can negotiate their participation in the company. Conversely, any strengthening of their participation in the company, especially if it is financed by debt, will be a very positive signal for the market.

The preference theory or pecking order theory, initially presented by Myers and Majluf (1984), justifies the prioritization of funding methods. It assumes that managers choose the sources of finance with the lowest intermediation costs and agency costs. First, companies favor self-financing, i.e. internal financing. It does not require the submission of a file or any negotiation with third parties. In addition, dividend payment targets are tailored according to their investment opportunities. Then, depending on the year, if the results and opportunities are variable, companies use their cash flow. If the financing needs of investments exceed the amount of self-financing, companies resort to external financing. They first choose to issue low-risk debt, i.e. with guarantees for lenders. Likewise, if companies cannot call on traditional debt, they issue debt securities (from the less risky to the riskier). Finally, if the sources cited above prove to be insufficient, companies issue shares and carry out capital increases.

Agency theory takes place in a context of information asymmetry. The agency relation is a contract by which one person (the principal) appoints another person (the agent) to perform certain tasks. This contract implies that the principal delegates part of their decision-making authority to the agent. This relationship is problematic since the interests of the two parties are different. This produces a number of costs that are necessary for executives, for example, to behave in the best interests of the shareholders who appointed them. Agency theory is an attempt to draw a parallel between financial theory and the theory of organizations.

Agency costs can be due to debt. Indeed, in the situation of nearly reaching bankruptcy, a company with debt may accept risky, unprofitable projects (the net present value or NPV is negative), which reduces its value. This practice implies an increase in the value of equity at the expense of that of debt. Shareholders exclude the capital increase for fear of abandoning their contribution to creditors. However, this recapitalization makes it possible to carry out profitable projects. In this case, the agency costs represent the shortfall resulting from rejecting the project for lack of funding. Managers tend to make decisions in favor of the shareholders. These decisions may take the form of company-funded gifts or restrictions on the research and development budget (in order to optimize the distribution of dividends). These practices weaken the competitiveness of the firm and its ability to generate the cash flows that can be used to repay debt. As a result, lenders increase their requirements (agency costs) and insert protection clauses in their contracts. Smith and Warner (1979) have studied the role of these clauses which protect creditors from deviant behavior by shareholders.

Agency costs of equity are the result of disagreements between providers of capital and managers. They relate to companies with a large number of shareholders, which leads to a disconnect between the ownership and the management of the firm. These conflicts, studied by Jensen and Meckling (1976), are due to decisions taken by managers to the detriment of stakeholders. This may be excessive compensation and the allocation of benefits in kind, or inefficient use of surplus cash, instead of increasing the distribution of dividends. This results in the acquisition of marketable securities, whose NPV is equal to 0, that the shareholders could have bought if the company had distributed more dividends or by the acquisition of firms whose activity is not controlled by the company, with the initial aim of diversifying assets. In these cases, the enterprise value falls due to negative NPVs. This decrease corresponds to the agency costs of equity. As Charreaux (1997) explains, shareholders cannot control the deviant behavior of the leaders they have appointed. However, by resorting to debt, which can increase the risk of a company becoming bankrupt, the intention is to support the motivation of managers to make optimal decisions for the company and therefore for its shareholders.

The manager who is not a shareholder seeks to avoid debt which increases the company risk (increase in the breakeven point, financial costs and repayment deadlines that need to be respected) and therefore its own risk (as their income mainly comes from the company). As a precaution, they’ll tend to want to accumulate liquidity in the company rather than invest it in risky projects. This behavior is not in the shareholder’s interest, as they diversify their assets and perceive the state of being in debt as a stimulus for the manager, and so is encouraged to do their best to free up the cash flow available for the payment of financial expenses and to meet repayment deadlines. In other words, shareholders have an interest in debt to put management under pressure and thereby solve agency problems. The explicit cost of debt constitutes a powerful force impacting the company’s management team. Insofar as the parameters of debt are reflected in the company’s cash flow while financing via equity results in capital gains or losses at shareholder level, managers have all the more interest in the success of their investments as they are financed by debt. From here, questioning the theory of markets in equilibrium entails a second degree of questioning: the mode of finance influences the choice of investments to the extent that the different forms of finance do not give the same incentives to the business leaders. This means in turn that a company with debt would be more flexible and react faster than a company that is not in debt. The hypothesis has been empirically verified by Ofek (1993). He argues that companies that are listed in the US react (go bankrupt, cut dividends, experience layoffs, etc.) even faster to being in a lot of debt than when they are in a situation of crisis. When it preserves a balanced financial structure, debt is thus one of the modes of internal control that shareholders would choose when it comes to managers6 .

In this context, the exercise of business valuation is paramount for each of the stakeholders. Indeed, insofar as a company can buy and be bought, its valuation is of particular interest to investors who look to justify their decision to enter, lend or exit the share, with the manager enabling him/her to position the structure in relation to his/her peers, with the objective of adjusting their management. Therefore, considering the potential value of the company, the market will facilitate the development of financing.

1.3. Valuation measures and follow-up measures

Valuation consists of economically valuing the equity of a company. They can be valued directly or indirectly, i.e. by characterizing the overall value of the company and then deducting the amount of net debt from it in particular. There are three traditional methods.

The comparables method seeks to compare companies or assets of the same nature by focusing on forecasts of aggregates of the income statement and, possibly, of the short-term balance sheet (one or two years of forecast data are necessary as well as aggregates from the last fiscal year). Equity is thus valued by stock market or transactional comparisons.

When the development prospects are considered in the medium or long term, the method of discounted cash flow suggests calculating an intrinsic value of the target company. It results from the calculation of normalized future cash flows from operating income, thus excluding financial expenses, exceptional items and the payment of dividends. Discounting is based on the weighted average cost of capital (WACC). This incorporates the cost of equity and debt found in the CAPM. The value of equity is ultimately obtained by subtracting the value of net debt in particular.

Finally, the proprietary approach evaluates the company as a sum of its assets discounted from net debt. When setting up holding companies, the valuation of revalued net assets recommends restating the equity of hypothetical assets and liabilities before adding unrealized capital gains to them and subtracting unrealized capital losses. In the case of conglomerates, the estimated net assets seek to define, for each branch of activity, an enterprise value obtained by carrying out the assessment presented above. The sum of the various values corresponds to the enterprise value of the conglomerate from which the consolidated net financial debt is deducted to estimate the value of equity. After having evaluated the target, the acquisition can take place on condition that the financing processes have been completed and that the initiator’s earnings per share have been assessed, possibly to include the synergies generated by the acquisition.

1.3.1. Evaluation by comparative approach

Valuation by stock market comparisons is a method used to determine an objective stock market price of a company and in the context of a public offer when the offer price is presented. It is based on forecasts of financial aggregates. The company is valued for a multiple of its earning capacity, and the markets in equilibrium justify comparisons. This approach is holistic, focusing not on the value of operating assets and liabilities, but on the profitability of their use. The multiple becomes higher as the growth prospects become stronger. The sector of activity is slow risk, and the interest rate charged is low. The valuation of a company is carried out on the basis of a repository of companies that present the same industrial risk. For each of them, multiples of the income statement aggregates are calculated.

This is done by establishing the enterprise value of each company in the sample and relating it to the aggregate in question. Then, an average is taken for each category of multiples. The sector multiples formed from there are applied to the corresponding aggregate from the company that is under valuation. The various corporate values that are then defined are eventually restated, which results in economic values of equity. Depending on the financial specificities of the sector, the relevance of certain multiples will be justified. In addition, these multiples may be taken from a sample of companies that have recently been sold, and for which an equity value has been expressed. Therefore, a company’s shares will be valued using the first type of sample if there is no change in control to be noted and a company’s equity will be valued using the second type of sample, in case of a change in control. Using the share price to calculate the market multiples provides a “minority” value; the transaction multiples result in “majority” values because they include a control premium. There are two categories of multiples: those that establish enterprise value (multiples of aggregates before financial charges) and those establishing equity (multiples of aggregates after financial charges). Enterprise value EV is the economic value of operating assets. Since the balance sheet is in equilibrium:

where

- – MC: market capitalization;

- – MI: minority interests;

- – ND: net financial debt;

- – FA: financial assets.

Enterprise value therefore corresponds to the market value of the industrial and commercial tool. Fixed assets are excluded from this concept insofar as this enterprise value is intended to be compared with sales, gross operating surplus and operating income which do not include financial results. In addition, when restating the enterprise value that makes it possible to economically valuate the shareholders’ equity, net debt is notably subtracted, i.e. the financial debt to which investment securities and liquid assets are added. It is therefore necessary to add, during this last step, the financial fixed assets which differ from investment securities only in terms of where they are used. For its part, the net financial debt is made up of all short-, medium- and long-term financial debts, from the value of hedging instruments minus cash flow assets (liquid assets and transferable securities). Theoretically, the value of net debt preserves its market value, i.e. it is equal to the value of future flows to be paid (interest and capital) discounted at the market cost of the debt at which we can subtract the market value of financial investments. We can also use the market value of debts listed and/or traded within an over-the-counter market (bonds, syndications, credit derivatives or CDS). In practice, the market value is often equal to the carrying value (Le Fur and Quiry 2004). The two values are significantly different when:

- – the company is indebted at a fixed rate by means of a swap and the interest rates have fluctuated in the meantime;

- – the solvency has undergone a significant change after the company has contracted a debt without the interest having been adjusted;

- – the nominal rate of the debt has been artificially reduced by the addition of warrants (or other detachable products after the issue).

Finally, market capitalization corresponds to the economic value of equity. If the company is listed, it is equal to the number of shares multiplied by the market price7.

Throughout this work, the provisions have not undergone any restatement for the following reasons:

- – differences in accounting standards IFRS and US GAAP in particular lead to significant discrepancies8;

- – in practice, analysts can assume that they are integrated into the result (thus in equity);

- – theoretically, provision for pensions can be assimilated to a financial debt towards employees (Le Fur and Quiry 2003). In practice, analysts can reintegrate it directly into net debt. It is readjusted each year in order to take into account when it is updated9. It is similar to a zero coupon bond for which each year the company recognizes an interest charge payable only at the end date. However, if the retirement provision is taken into account when calculating the enterprise value, it is essential to ensure that the EBITDA and the operating profit do not include the fraction of the allowance that corresponds to the passing of time.

And so, the multiple of turnover (TO) shows that the value of operating assets is equivalent to a certain number of times the turnover:

This multiple is of particular interest for a sample which displays a normative and relatively low economic profitability. Otherwise, the results obtained will be heterogeneous. In addition, this multiple makes sense for SMEs for whom turnover is much more indicative of real profitability than the net result published, where transactions are numerous. Finally, this multiple is to be avoided when comparable companies are profitable because in this case it will tend to overvalue the company. In the equation, by replacing the TO by the EBITDA and by the EBIT, we have:

The multiple of operating profit makes it possible to enhance the profitability of the company by excluding non-recurring items.

The multiple of gross operating surplus eliminates any significant differences in investment and related repayment choices. The multiple is particularly suited to capital-intensive industries. However, despite the choice of depreciation arrangements, this multiple loses its usefulness in the case where the margin levels of the sample are different.

Companies with low margins are then overvalued, while the opposite effect occurs for those with high margins. P/E is the ratio of the share price to earnings per share. It corresponds to a direct approach10:

Income generated by financial assets is included in net income. In addition, the net result is “shared within the group”. This is the reason why no restatement of financial assets and minority interests is to be made.

In practice, net income is restated for non-recurring items and goodwill impairment in order to facilitate an analysis of recurring earning capacity. Indirectly, this multiple based on an aggregate after financial expenses values the financial structure of the company. Thus, if the sample’s debt levels are disparate, the valuation may be skewed. This is the reason why, in order to break away from heterogeneous financial structures, the multiple of operating income and, to a lesser extent, that of gross operating surplus are used more.

Based on the estimates of analysts, it is customary to calculate the multiples of comparables on the forecast values of the income statements of companies in the benchmark and the target, always considering the last published financial year. The question then arises as to whether the corporate values should be current (i.e. corresponding to the last published financial year) or whether they can also be forecast. Indeed, the second method fully integrates the investment and financing policy of the company (Le Fur and Quiry 2007). In other words, it seems theoretically irrational to consider, in the multiple of operating income, the investments made in year N+1 (through estimated depreciation) without including in the calculation of the financing linked to these (through “new” equity and/or “new” debt).

By incorporating the notion of forecast value, this method would be granted the ability to differentiate between company multiples with distinct investment and growth profiles. However, the practice tends to go against this reasoning due to the fact that if we were to calculate the value of asset N+1 of the company, we can estimate the net debt N+1. It is, however, impossible to guess the market capitalization N+1. We could propose to capitalize the value of equity N at the cost of capital minus the rate of return.

However, empirically, this method is not used because the market incorporates known future data, through the share price and therefore the market capitalization. Furthermore, the operating profit multiple could be biased if the company is largely financed by debt: the multiple would be unfairly very high. Finally, the other elements allowing the transition from enterprise value to that of equity are most often considered constant because it is difficult to predict. Therefore:

- – to value a company in year N+1, it is advisable to keep the same value of the economic assets of the comparable company as for the year N11. In any case, the market value of the latter at the valuation date results from the anticipation of how its future operating balances will evolve;

- – if a comparable company has a strong investment policy, it is better to exclude it from the sample rather than wanting to wrongly improve the method of evaluating comparables.

The different economic values of equity allow us to compare the company under valuation to its competitors:

- – if the value of equity on the basis of the EBITDA multiple is higher than that of turnover, the assessment is more favorable for the company subject to the study since its EBITDA margin is greater than those of its competitors. This point can be verified by comparing the EBITDA margins of the sector with that of the company to be valued;

- – if the value of equity on the basis of the multiple of EBIT is higher than that of EBITDA, the valuation is more favorable for the company subject to the study because it has less depreciation and provisions than its competitors. This may reflect a weak investment policy that may reflect a problem of competitiveness;

- – if the value of equity based on P/E is greater than that based on EBIT, the valuation is more favorable for the company subject to the study because the leverage effect is used more intensively.

In order to use the transaction multiple method, the sample is built from the information available on transactions observed in the near past in the same sector of activity (among listed and unlisted companies) and from the moment when a change of control has been observed. The acquirer has logically paid an offer price which, in this case, appears as enterprise value.

This price paid incorporates a control premium (of the order of 20–25% of the company’s value) which is essential to take possession of the target and which results from a valuation of a share of the anticipated synergies. For each of the companies in the repository, we determine the multiple of turnover, EBITDA, EBIT, P/E of the last financial year closed on the date of the transaction. In other terms, for a transaction carried out in year N, we consider the aggregates of year N-1. For the numerator, the transaction amount replaces the market capitalization. Finally, each average transactional multiple obtained is applied to the homologous aggregate of the company under valuation.

By way of illustration, it was decided that the market comparables method would be applied to value the Royal Dutch Shell company, using a benchmark of companies from the oil industry. Royal Dutch Shell is an Anglo-Dutch company that specializes in energy and petrochemicals. The core business function is to refine and distribute petroleum and natural gas (90% of its turnover at the end of 2013).

The group owns more than 30 refineries and a network of around 44,000 service stations around the world. Around 40% of its activity is carried out in Europe, 35% in Asia-Oceania-Africa and around 25% on the American continent.

On December 5, 2014 (its valuation data), Royal Dutch Shell shares were listed at €27.26 at the opening of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange (AEX Index). Although of different sizes, the companies selected to constitute a reliable repository were Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Conoco Phillips, Petrobras and Total SA.

For the sake of homogenization, the amounts processed – namely the market capitalizations and the data of the balance sheet and income statement aggregates (realized or forecasted) – are expressed in dollars and then, to proceed with the valuation of the share, are quoted in euros, and so a conversion into the European currency is carried out. Moreover, on December 5, 2014, the EUR/USD parity was 1.2282 (parity applied to the benchmark aggregates of Total SA) and the USD/BRL parity was 2.5894 (parity applied to the benchmark aggregates of Petrobras).

Company aggregates for 2013 are taken from financial statements published by oil companies. The 2014 and 2015 forecast data and market capitalization are taken from zonebourse.com.

The multiples of the aggregates of the companies and the average multiples, assimilated to the sector multiples, are shown in Table 1.2.

Applying the average multiples to the corresponding aggregates for Shell finish the valuation12.

The results of this valuation approach are represented in Figure 1.4.

Table 1.1. Financial aggregates of the companies in the framework (amounts in millions of $)

| Market capitalization (05/12/14) | Net debt | Financial assets | Minority interests | Enterprise value | |

| Exxon Mobil | 397,283 | 18,055 | 36,328 | 6,482 | 385,492 |

| Chevron | 209,591 | 3,915 | 25,502 | 1,314 | 189,318 |

| Conoco Phillips | 83,517 | 15,416 | 23,907 | 402 | 75,428 |

| Petrobras | 59,433 | 94,579 | 6,666 | 596 | 147,942 |

| Total SA | 131,990 | 21,027 | 18,182 | 2,802 | 137,636 |

| Sales | EBITDA | EBIT | Net income | |||||||||

| 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | |

| Exxon Mobil | 438,255 | 417,504 | 379,124 | 74,902 | 72,980 | 63,016 | 57,720 | 54,835 | 43,024 | 32,580 | 32,674 | 27,706 |

| Chevron | 228,848 | 214,418 | 184,158 | 63,154 | 47,550 | 42,703 | 48,968 | 31,341 | 24,313 | 21,423 | 19,618 | 16,974 |

| Conoco Phillips | 58,248 | 56,635 | 54,194 | 23,455 | 21,911 | 20,221 | 14,446 | 12,669 | 9,996 | 9,156 | 7,982 | 6,371 |

| Petrobras | 141,462 | 154,934 | 164,128 | 29,426 | 32,204 | 39,958 | 16,083 | 17,110 | 22,208 | 10,832 | 9,464 | 13,121 |

| Total SA | 232,795 | 214,493 | 200,870 | 35,034 | 35,408 | 35,037 | 24,915 | 22,754 | 21,205 | 10,637 | 12,720 | 13,000 |

*Forecasts zonebourse.com

Table 1.2. Stock market repository of repository companies

| xSales | xEBITDA | xEBIT | P/E | |||||||||

| 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | 2013 | 2014* | 2015* | |

| Exxon Mobil | 0.88 | 0.92 | 1.02 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 9.0 | 12.2 | 12.2 | 14.3 |

| Chevron | 0.83 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 4.4 | 3.9 | 6.0 | 7.8 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 12.3 |

| Conoco Phillips | 1.29 | 1.33 | 1.39 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 5.2 | 6.0 | 7.5 | 9.1 | 10.5 | 13.1 |

| Petrobras | 1.05 | 0.95 | 0.90 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 3.7 | 9.2 | 8.6 | 6.7 | 5.5 | 6.3 | 4.5 |

| Total SA | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 5.5 | 6.0 | 6.5 | 12.4 | 10.4 | 10.2 |

| Sector multiple | 0.93 | 0.95 | 1.00 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 6.1 | 6.7 | 7.5 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 10.9 |

*Forecasts zonebourse.com

The valuation by the multiple of EBITDA is lower than that resulting from the turnover, given the profitability differential between the sector and Shell, to the detriment of the Anglo-Dutch company. Its EBITDA margin is lower (about 13% for Shell vs. about 24% for the sector). The valuation resulting from the multiple of EBIT is in line with that which results from the multiple of EBIDTA, which comes from an equivalent proportion of depreciation and impairment between the sector and Shell. The valuation by the P/E is lower than that which came from the EBIT. The valuation could improve if the company had recourse to debt, provided that its economic profitability was greater than the cost of its debt. Therefore, it is necessary to exclude the valuation that results from the turnover multiples because the profitability differentials between Shell and its competitors are not taken into account: applying the turnover multiple will overvalue the share.

Table 1.3. Valuation of Royal Dutch Shell by stock market comparisons (amounts in millions of $)

| xSales | xEBITDA | |||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| SHELL Aggregate | 451,235 | 448,379 | 423,292 | 59,864 | 60,436 | 57,160 |

| SHELL EV | 418,643 | 424,583 | 425,257 | 243,244 | 256,093 | 250,494 |

| (Net debt 2013) | (34,866) | (34,866) | (34,866) | (34,866) | (34,866) | (34,866) |

| Financial assets 2013 | 39,328 | 39,328 | 39,328 | 39,328 | 39,328 | 39,328 |

| (Minority interests 2013) | (1,101) | (1,101) | (1,101) | (1,101) | (1,101) | (1,101) |

| Economic value of equity | 422,004 | 427,944 | 428,618 | 246,605 | 259,454 | 253,855 |

| Number of shares (millions) | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 |

| Target share price ($) | 66.24 | 67.17 | 67.28 | 38.71 | 40.73 | 39.85 |

| Target share price (€) | 53.93 | 54.69 | 54.78 | 31.52 | 33.16 | 32.44 |

| xEBIT | P/E | |||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |

| SHELL Aggregate | 38,355 | 33,905 | 32,781 | 16,371 | 21,379 | 22,088 |

| SHELL EV | 233,881 | 228,654 | 245,496 | |||

| (Net debt 2013) | (34,866) | (34,866) | (34,866) | |||

| Financial assets 2013 | 39,328 | 39,328 | 39,328 | |||

| (Minority interests 2013) | (1,101) | (1,101) | (1,101) | |||

| Economic value of equity | 237,242 | 232,015 | 248,857 | 160,416 | 213,627 | 240,663 |

| Number of shares (millions) | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 | 6,371 |

| Target share price ($) | 37.24 | 36.42 | 39.06 | 25.18 | 33.53 | 37.78 |

| Target share price (€) | 30.32 | 29.65 | 31.80 | 20.50 | 27.30 | 30.76 |

Figure 1.4. Summary of valuations by stock market comparisons of shares from Royal Dutch Shell (in €)

In addition, it is wise to rule out the valuation that results from the P/E to the extent that any leverage effect is taken into account in a context where financial structures are heterogeneous. Thus, market capitalizations, which are too disparate between Shell’s competitors, do not constitute a relevant benchmark. The target price therefore corresponds to the average of the valuations that result from the EBITDA and EBIT multiples for 2013, 2014 and 2015. Based on the market comparables method and the price on December 5, 2014 (€27.26), the share appears to be undervalued. According to the study carried out, in the medium term, the upside potential may lead the share to list €31.48, i.e. an equity valuation of €200,569 million or $246,338 million (market capitalization on December 5, 2014 is €175,569 million or $215,634 million).

The method used in this application, based on short- and medium-term forecasts, excludes the potential for business development and improvement of long-term profitability. The discounted cash flow (DCF) approach allows us to assess the economic value of operating assets over a much broader space and timeframe using a financing plan. In other words, it is about finding the enterprise value that comes from the sum of the discounted future free cash flows (FCF) generated by the activity of the company to be valued.

1.3.2. Flow assessment

The economic value of equity can be obtained following two methods. The first consists of considering that the income of a company’s shareholder is made up of dividends received and the market value of the shares that are on resale. Therefore, enterprise value should be based on the sum of the future dividend flows payable by the enterprise and the market value of the stocks at the end of the expected space–time horizon. The second method for obtaining the economic value of equity consists first of estimating the value of the economic asset before subtracting from it the amount of net debt as well as minority interests, before adding the value of fixed assets.

1.3.2.1. Dividend discount model

Assuming that the expected space–time frame is infinite, the dividend discount model will not incorporate capital gains since it does not affect the valuation of the share. This notion is thus formalized and an intrinsic value of the company is defined as the present value of future dividends discounted at the cost of equity. Thus, we have:

where:

- – Vt: intrinsic value of equity in time t;

- – Dt: dividends expected at the period of time t (with information being available at the time t-1);

- – k: cost of equity given the CAPM formula.

Let’s assume that the dividends have an annual growth rate g:

And so:

Knowing that:

because if ![]() .

.

Here:

We therefore have the formula expressed by Gordon and Shapiro (1959):

Applied when the company to be valued operates in a mature sector with good visibility (public services, real estate companies, etc.) with a high dividend distribution rate, this method nevertheless has the weakness of not taking into account the organic growth via resources set aside. In practice, many younger companies with high growth potential tend to keep most of their profits or, with a finite forecast horizon, they have no intention of paying dividends. Therefore, the market values of this type of company are larger than those found through the Gordon and Shapiro equation. What is more, according to Modigliani and Miller (1963), the value of a share is not linked to the date that the dividends were paid. It is not uncommon to come across a company that is borrowing funds in the markets in order to be able to remunerate its shareholders, this all being without any apparent link with operating activities or with an investment policy which has created value. The DDM thus focuses on distributing money to shareholders by assuming a consistent distribution without necessarily having any link to the creation of value.

1.3.2.2. Discounted cash flow model

The economic value of operating assets results from calculating the enterprise value. It corresponds to the sum of the discounted future free cash flows that have been generated. Subsequently, the net debt and minority interests are subtracted from it, then financial fixed assets are added to it. We can then obtain the economic value of the equity. In order to find the value of the operating economic asset in the first place, we may apply the technique of choosing the investments that are based on some sort of reasoning:

– in terms of cash flow and not in terms of accounting results. This makes it possible to take into account the variation in the working capital requirement, i.e. the impact of payment delays. In addition, depreciation is calculated according to tax and accounting rules and does not always correspond to an economic reality. An amount only costs or yields at the very time of disbursement or collection, regardless of the treatment given to it. Beyond that, the reasoning is carried out more in terms of opportunity than accounting. Indeed, the account or historical value is of no interest except for tax purposes to know the tax paid on capital gains or tax credits obtained in the event of book value losses. The asset has value, i.e. it corresponds to the acquisition price in the event of investment and to the resale price in the event of divestment;

– in terms of flows induced by operation and investment only. Thus, financing flows are discarded because the cash flows are intended to be discounted at the weighted average cost of capital; the purpose of the calculation being to compare the profitability of investments with the cost of financing. This eliminates financial charges, capital repayments and dividend payments;

– in matters of taxation. Depreciation results in tax savings. The results of the investments are taxed. Depending on the type of investment, the company may benefit from tax credits, allowances, subsidies, etc.

Therefore, the FCF17 are determined using the taxed operating income (tax is a disbursement). Depreciation (net allocations of reversals), which reduce operating income without reducing cash flow, must be reinstated. In addition, in order to neutralize the receivable income not yet collected and the disbursable expenses not yet disbursed, the change in WCR must be deducted. Finally, net investments of divestments that are not taken into account in the aggregates mentioned constitute disbursements. They must be deducted.

The value of operational assets V equal to the sum of the discounted future FCF is written as so:

with:

This method therefore involves determining the cash flows up to infinity. To achieve this, updated forecasts are made over an explicit horizon (5–7 years or even 20–30 years in utilities services) and beyond this horizon, a terminal value is considered18. The duration that characterizes the explicit horizon must correspond to the time during which the company will live on its current momentum. If it is too short, the valuation will rely excessively on the terminal value. If it is too long, the valuation will be the subject of a simple theoretical extrapolation. In addition, a growth rate g is applied to the final value. At first glance, it is difficult to estimate the terminal value since the date from which it is defined is synonymous with presumption when making forecasts. Therefore, analysts consider that at the end of the explicit horizon, the company has reached its maturity phase. Using the Gordon and Shapiro formula, the most commonly used terminal value is derived from an infinite growth rate g applied to a normative flow. The way it can be characterized is the consequence of the investment policy and the evolution of the company’s working capital needs. Moreover, it may not be equal to the last flow of the explicit horizon if the activity sector is cyclical because in this case, it would correspond to an average flow generated by the company up to infinity, while the growth forecast for this last year of the business plan would significantly differ from g.

However, it is necessary to question the sustainability of market growth and the economic profitability of the company. It would be unfounded to assume a growth rate g that is significantly higher than what analysts expect for long-term genuine growth (net after inflation). This would mean that the company to be valued would gain more and more importance in the economy over time. The “diminishing rent” model proposes to converge the expected economic profitability of the company towards the cost of capital. This model of cash flow fade makes it possible to create a moment at which the economic profitability deteriorates until it becomes equal to the weighted average cost of capital. This moment would come to pass between the end of the business plan and the terminal value. This can be explained by the decline in margins or by the decline in turnover of economic assets. At the end of the horizon, the final value is equal to the economic asset for its book value. Finally, this model can be applied to a company that is destroying value. In this case, the use of cash flow fade is justified, by assuming that the industry in question cannot remain in the same situation indefinitely. The structural changes, brought about sooner or later by bankruptcies or by market saturation, will make the flows of the company to be valued approach the cost of capital, allowing it to survive (thanks to the growth of economic profitability). Thus, several scenarios can be considered depending on whether we consider the point of view of the prospective buyer or the seller. Negotiations between the two parties will then make it possible to reconcile the valuations of the prices. In practice, the DCF method can be an appropriate dialogue tool. The rate used to discount FCF is the weighted average cost of capital (WACC), which is the weighted average cost of the company’s financial resources. It represents the minimum rate of return required by fund providers to finance the business. This situation results from the “fungibility” of the balance sheet. It is impossible to determine from a company’s accounts the financing of a given asset. Consequently, each asset is financed by equity E and by debt D; the weight of the first and the second in financing each asset corresponds to the weight of each resource in the economic balance sheet of the company. We then have:

where:

- – K: CMPC;

- – k: cost of equity;

- – i: cost of debt;

- – t: tax rate.

The economic value of the equity required to determine the WACC and therefore the discount rate is precisely what the DCF method should achieve. This is an iterative approach that loops through the value of equity. Approximating a listed company allows us to preserve market capitalization in the WACC formula. Equity value is the difference between EV enterprise value, net financial debt, minority interests, provisions to which financial fixed assets are added. Therefore, maximizing enterprise value through discounting future cash flows leads us to consider the possible existence of an optimal financial structure.

By way of illustration, it was decided that the DCF method would be applied to value the company Royal Dutch Shell. Table 1.4 presents the elements of the financing plan for the Anglo-Dutch company.

In order to extend the business plan from 2017, the assumptions are as follows:

– the growth rate of turnover is estimated at 3% by 2021. Consequently, from 2017 to 2021, there is a linear convergence between the growth rate of the last forecast year (2.2% in 2016) towards the last year of extension (3% in 2021);

– the EBITDA margin rate 2016 (14.1%), the allocations/turnover ratio in 2016(6.1%) and the corporate tax rate in 2016 (44%) are maintained from 2017;

– the amount of investments in 2021 is equal to the level of allocations planned for the same year ($29,941 million). This results from the assumptions that the company is fully mature by 2021, which then leads it to renew its stock of fixed assets at the rate of its allocations. And so, from 2017 to 2021, there is a linear convergence of the amount of investments for the last forecast year ($34,238 million in 2016) to the level of allocation of the last year of extension ($29,941 million in 2021);

– the WCR is considered to be normative. Consequently, the WCR/turnover ratio observed in 2013 (3.3%) is maintained from 2014 to 2021. From here, we deduce for each year the variation in WCR which comes with the reduction of free cash flows.

Table 1.4. Valuation by DCF of Royal Dutch Shell (amounts in millions $)

| Production | Sourced from zonebourse.com | Extension | |||||||

| 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | |

| Turnover | 451,235 | 448,379 | 423,292 | 432,800 | 443,174 | 454,465 | 466,729 | 480,027 | 494,428 |

| Growth rate | -0.6% | -5.6% | 2.2% | 2.4% | 2.5% | 2.7% | 2.8% | 3.0% | |

| EBITDA | 59,864 | 60,436 | 57,160 | 60,885 | 62,344 | 63,933 | 65,658 | 67,529 | 69,555 |

| EBITDA margin rate | 13.3% | 13.5% | 13.5% | 14.1% | 14.1% | 14.1% | 14.1% | 14.1% | 14.1% |

| (Depreciation allowances) | (21,509) | (26,531) | (24,379) | (26,209) | (26,837) | (27,521) | (28,264) | (29,069) | (29,941) |

| In % of TO (turnover) | -4.8% | -5.9% | -5.8% | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% | -6.1% |

| EBIT | 38,355 | 33,905 | 32,781 | 34,676 | 35,507 | 36,412 | 37,394 | 38,460 | 39,614 |

| (Corporation tax) | (17,066) | (14,918) | (14,424) | (15,257) | (15,623) | (16,021) | (16,454) | (16,922) | (17,430) |

| Tax rate | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | 44.0% | |

| NOPAT | 21,289 | 18,987 | 18,357 | 19,419 | 19,884 | 20,391 | 20,941 | 21,537 | 22,184 |

| Depreciation allowances | 21,509 | 26,531 | 24,379 | 26,209 | 26,837 | 27,521 | 28,264 | 29,069 | 29,941 |

| (Net investments) | (40,146) | (33,495) | (33,726) | (34,238) | (33,379) | (32,519) | (31,660) | (30,800) | (29,941) |

| (DBFR) | (2,988) | 94 | 829 | (314) | (343) | (373) | (405) | (439) | (476) |

| FCF | (336) | 12,117 | 9,839 | 11,076 | 13,000 | 15,019 | 17,140 | 19,367 | 21,708 |

| Discount period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

| Discounted FCF | 11,359 | 8,646 | 9,123 | 10,038 | 10,872 | 11,630 | 12,319 | 12,944 | |

| WCR | 14,904 | 14,810 | 13,981 | 14,295 | 14,638 | 15,011 | 15,416 | 15,855 | 16,331 |

| WCR/TO | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% | 3.3% |

Table 1.5. Determining the weighted average cost of capital of Royal Dutch Shell

| Risk-free rate | 1.00% |

| Market risk premium | 5.74% |

| SHELL Beta | 1.08 |

| Cost of equity (k) | 7.22% |

| Cost of debt (i)... | |

| ... before tax | 4.37% |

| ... after tax | 2.45% |

| Discount rate (WACC = K) | 6.73% |

| Growth rate to infinity (g) | 3.00% |

In order to determine the discount rate:

– the risk-free rate (corresponding to the 10-year OAT rate) which was used is 1%19;

– the market risk premium was obtained by first constituting a benchmark, all sectors of activity combined, of about 300 companies listed on the CAC 40, AEX, DAX, FTSE 100, FTSE MIB, l’IBEX 35, PSI 20, Dow Jones, Nasdaq and Nikkei 225. Then, for each of the companies in the sample, the quotes at the opening of the stock market on December 5, 2014 were retrieved as well as the estimate of the next dividend paid and the beta of the share20. Assuming, on the other hand, an infinite growth rate of 3%, the risk premiums for each company were calculated according to the Gordon and Shapiro equation:

where:

– V0: share price i on December 5, 2014;

– D1: estimate of the next dividend paid linked to the share i;

– βi beta of share i;

– rf: risk-free rate;

– E(Ri) – rf: equity market risk premium of share i.

The market risk premium is therefore equal to the average of the 300 values thus calculated, i.e. 5.74%;

– the beta of the Royal Dutch Shell share was obtained by establishing a repository of companies belonging to the same sector of activity as the Anglo-Dutch company. The oil companies chosen are Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Conoco Phillips, Petrobras and Total SA. For each of them, the (indebted) beta of the shares was recovered as well as the net debt and market capitalization21. Then, for each of the companies in the benchmark, the debt-free beta was calculated using Hamada’s formula (1972):

| Beta | Net debt | Equity | Debt-free beta | |

| Exxon Mobil | 0.9 | 18,055 | 397,283 | 0.88 |

| Chevron | 1.15 | 3,915 | 209,591 | 1.14 |

| Conoco Phillips | 1.07 | 15,416 | 83,517 | 0.97 |

| Petrobras | 1.83 | 94,579 | 59,433 | 0.97 |

| Total SA | 1.11 | 21,027 | 131,990 | 1.02 |

The average debt-free beta (0.99) corresponds to the debt-free beta in the sector. Finally, the following is applied to the financial structure of Royal Dutch Shell:

The (re)indebted share of Royal Dutch Shell is at 1.08;

– the cost of equity (7.22%) is obtained by applying the CAPM formula;

– the cost of debt is determined according to the Standard & Poor’s debt rating guide. As of January 17, 2014, Shell bonds are rated according to the AA rating agency and the associated cost of debt is 4.37% before IS (i.e. 2.45% after tax);

– the FCF is discounted using the weighted average cost of capital (6.73%) by performing an iterative calculation of the WACC (closure on the desired value);

– the infinite growth rate (3%) is the assumed rate, in accordance with the assumption made in corporate and investment banks, and is in line with the method for determining the market risk premium.

The 2013 balance sheet shows a net financial debt of $34.9 billion. Enterprise value ($298.6 billion) is equal to the sum of discounted FCF over the business plan period ($86.7 billion) and the terminal value ($211.9 billion). The economic value of equity ($302 billion) is obtained by deducting new debt, minority interests and auditing financial assets to the enterprise value. Shell’s target price is thus $48.4 or €38.59 (the stock market price is €27.26 on the valuation date, December 5, 2014).

| Sum of DCFs 2014-2021 | 86,745 |

| Terminal value | 211,855 |

| Enterprise value | 298,600 |

| (Net debt) | (34,866) |

| Fixed assets | 39,328 |

| (Minority interests) | (1,101) |

| Equity | 301,961 |

| Number of shares (millions) | 6,371 |

| Target price ($) | 47.4 |

| Net result 2013 | 16,371 |

| Implied | 18 |

| Target price (€) | 38.59 |

Table 1.8. Sensitivity analysis of the value of Royal Dutch Shell at the risk-free rate and to infinite growth

| Risk-free rate | ||||||

| 1.0% | 1.5% | 2.0% | 2.5% | 3.0% | ||

| Growth rate g | 3% | 301,961 | 269,528 | 243,633 | 222,521 | 205,007 |

| 4% | 375,621 | 324,694 | 286,246 | 256,259 | 232,261 | |

| 5% | 515,810 | 420,578 | 355,472 | 308,274 | 272,563 | |

| 6% | 886,304 | 628,291 | 487,344 | 398,781 | 338,122 | |

Based on the discount rate and perpetual growth rate retained ad infinitum, the valuation is between $205 billion and $886 billion. The advantage of this method is to concretely translate the different assumptions and forecasts of buyers and sellers. A certain serenity is maintained in the face of periods of stock market overvaluation. It keeps economic performance grounded in reality. This method, satisfactory in theory, has three major drawbacks, however:

– is it very impacted by the assumptions and objectivity of the person who established it. Therefore, its results are very volatile. This is a rational method that can be biased;

– sometimes, it depends too much on the terminal value, to which the problem is ultimately transferred. Terminal value often explains 50% of the company’s value (Vernimmen 2012, p. 743). This can call into question its validity even though, sometimes, it is the only method applicable when the results are negative and the multiples are not applicable;

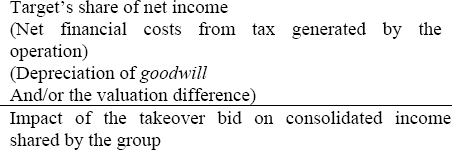

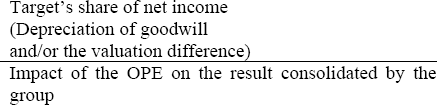

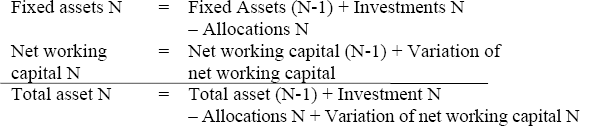

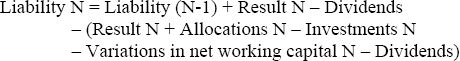

– it is not always easy to carry out a business plan over a sufficient period of time: the information is often lacking for the external analyst.