3 Films and how they work

1.Types of film and filmmakers

The aim of this section is to start thinking about what sort of filmmaker you want to become. Do you want to make films with straight stories, or are non-narrative films going to inspire you more? Does the music video allow you to be more imaginative than, say, a drama? Or do you ultimately want to make feature films?

Part of your task is to move as quickly as you can towards a position where you know what is out there and how you can break into it. Take your pick.

Narrative film

A narrative movie uses a story as its main motivation. Since the birth of cinema, narrative has been the driving force of the film industry, to the extent that other forms are described by how much or how little they address narrative. It evolved largely from the dominance of literary media in culture and borrows hugely from literature in the way stories are told, even down to the use of cutaways in editing. But as a primarily visual medium, film has other possibilities and many filmmakers have tempered the dominance of plot and increased the use of visual signs and symbols to develop the themes and meanings of a film, such as Stanley Kubrick and Andrei Tarkovsky.

Within narrative film there have arisen many conventions about how you tell a story. Largely due to the need to agree a common code with the viewing public which can be applied to each and every film, there are certain ways of shooting and editing that will disguise the actual process of filmmaking and draw attention only to the plot and the characters within it. Thus, film becomes a true escapist experience.

If you work with stories today, however, you need to possess some detailed knowledge of these conventions as if they are a set of signs that an increasingly knowing audience is going to decipher. This means that you can subvert conventions and can mix signs from different forms (for instance, by including parts of other genres, as in Tarantino’s Kill Bill), but all the time you have to be aware of where you stand within the wider framework of narrative film. Audiences develop their awareness of these signs in narrative film simply by seeing lots of films, so as a filmmaker you are equally able to read the signs and then perhaps make up your own.

Figure 3.1 Directing involves a range of skills from the technical to the artistic. Here, director David Casals sets up a shot for his short, Time Cocktail.

Narrative film may be the established dominant mode, but entering this area doesn’t mean you have to follow film trends, making cliché-ridden films that only emulate other directors. Certainly this may be true within the profit-driven industry of Hollywood, but there are numerous directors who follow their own path by turning narrative into something that is their own.

The short movie

In the last chapter we heard about how short movies (average 10 minutes in length or less) have had something of a comeback as the new filmmaker’s school. Almost all filmmakers have made several before going on to make successful features, the shorts serving as a place to try out ideas, road-test stories, and develop style and exercise conventions. The quick pace of short movie production also helps build confidence, as you can make one with very few resources or little time.

The micro-short

This development of the narrative movie is relatively new, resulting from the need for shorter-than-short movies that download fast over the Internet or to phones. The particular constraints of movies lasting less than a minute are invigorating, helping you to develop faster as a filmmaker. Straight narrative sits as easily as abstract movies in this form, although many narrative versions tend to be more successful because of the startling way they compress conventional storytelling into small spaces — temporally and spatially.

The narrative filmmaker obsesses about films to the degree that relationships end (and start) over top ten lists of movies. For their own work, they ride a wave of adrenaline, enjoy stress (‘I actually feel stressed now if I am not stressed, without anything to do.’ James Sharpe, filmmaker) and stop at nothing to get a film made. Theirs is a guerrilla world where night-time raids are made to scale the walls of mainstream cinema, funded by credit card. Organized and skilled, they survive on little sleep but are sustained through their strong — and deserved — sense of their own talent.

Weblink

http://www.nokiashorts.co.uk/ Annual competition for micro-shorts.

Documentary

Documentary has a long and honourable tradition of seeking the truth and dragging it out from under a rock, so it has been an exciting and provocative place for a filmmaker to work. But as the ways of big business and government have become more wily and shrewd, engaging spin and marketing to protect interests, so filmmakers have started to employ new means of cutting through them. Pioneering filmmakers such as Nick Broomfield, Morgan Spurlock and Michael Moore, who mix polemic with fact and personal insight, have made documentary one of the most energetic and stimulating places for a filmmaker to work. Crucially, films such as Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore) and Touching the Void (Kevin MacDonald) have convinced the industry that big financial returns are possible on what used to be a no-go area for Hollywood.

Figure 3.2 Documentary filmmakers need resilience to work in extreme conditions far removed from the comfort of the studio. In this still, Franny Armstrong, director of Spanner Films, prepares for her film Drowned Out.

What these and other filmmakers have done is make documentary as creative and interesting as narrative film. It allows the chance to put together a narrative and employ the creativity you would like to use in narrative film, but without the limitations of conventional storytelling.

My kind of people?

Within the filmmaking community, documentary makers tend to opt for projects others would give a wide berth. If this was the world of sports, they would be doing the extreme end — hang-gliding while blindfolded above the sierras. Discomfort and obstacles are their bread and butter and they look for problems, war zones, trouble spots the way most of us avoid them. Documentary makers live rough, work alone and leave their critics at base camp while they go and chase the next story.

Non-narrative

This encompasses a whole range of work where other elements of the film are dominant rather than plot. Here, visual meaning is the dominant factor. If we talked about plots as happening in a linear way (this happened, followed by that and so on), then these movies are non-linear. You take in the whole experience and then try to figure out what it was all about.

Experimental/art gallery films

Even finding a label for this kind of film is hard — many films experiment in some way, and not all films seen in galleries are experimental, and in any case, can they be called films? It is probably the most intriguing area of film to look at and yet the hardest to find; it is almost impossible to find such pieces at your local store and many artists cannot afford to commit their work to DVD for commercial sale.

These kinds of works radically break outside of the normal viewing confines we are used to. Films can be minutes, several hours or even years in duration (Douglas Gordon’s The Searchers slowed down the classic western to last five years — the duration of the eponymous search), may have no continuous action, recognizable events or places, and may rely on just a few essential images. What they do tend to focus on is a strong central theme on which everything rests. In Steve McQueen’s Wrestlers, two men occupy a large wall-sized screen as they square up to each other in slow motion. Slowly they collide and fight, then part, and so the film goes on. In Bill Viola’s recent work, using high definition video at ultra slow recording speeds, classical images are enacted such as group portraits, a figure walking in fire, being doused by a waterfall and so on. Probably the most successful video art relies on few images and on few themes for its impact. Editing is relegated to a secondary role, probably because of its artifice-inducing properties — editing lies, but the camera doesn’t. Another crucial ingredient is the use of place. Where the film is actually seen is more than just an important element — it is a central pillar of the work. Scale is often used in McQueen’s work, and so is the arrangement of screens, as in Gary Hill’s installations, where screens are arranged in sculptural shapes.

Figure 3.3 British-based group Blast Theory create stunning images by combining text, images and animation, as in this film, Desert Rain.

Weblinks

http://www.lissongallery.com/theArtists/Gordon/douglasgordon.html Background on video artist Douglas Gordon.

http://www.tate.org.uk/learning/schools/stevemcqueen2436.shtm Printable notes on Steve McQueen from UK’s premiere modern art gallery.

To get a background to this kind of work, look at early Andy Warhol movies such as Empire (1964), the eight-hour stationary shot of the Empire State Building, or work by Korean-American artist Nam June Paik, who developed a more sustained approach to her work.

My kind of people?

Focused is an understatement — these people live and breathe their ‘art’ just as much as any Hollywood image of Michelangelo or van Gogh. They have to be, though, as the financial return from living as a video artist is low. Museums and galleries will show your work but don’t expect to be paid, except in the more enlightened Nordic countries. The video artist is not a one-trick pony — they are adept at logistics, working with electronics and can turn their hand to most practical tasks. If not video artists they could just as easily run a military campaign — but would probably object to it, saying that the theme was not strong enough.

Figure 3.4 Music promo makers endure tough working conditions, but the stakes and rewards are high. This still is from Dominic Leung’s promo for Moloko, The Time is Now.

Music promo

The music promo occupies a peculiar position in films in that it is more a marketing device and can be either narrative or non-narrative. The entirely narrative promo is rare today and most have slim narrative threads on which to hang a series of crucial images. The idea of a short film that accompanies a piece of music grew out of films including A Hard Day’s Night (Richard Lester, 1964). This form has always been a primarily commercial one, since it is explicitly linked to the promotion of an artist for increased sales. But, as with the advertising commercial, there are increasing numbers of film directors who have found this form a place to define and develop their style. For many it is the freedom from narrative that is most liberating. It allows the director to focus purely on the visual aspects of a film and move far from the theatrical or literary aspects. For the emerging filmmaker, there are many reasons why this form is seen as the real-life film school: the fast production process means you make mistakes quickly and learn quickly, the tight budgets and strict client demands mean having to be creative with what you are given, and the short nature of the promo means having to grab a viewer’s attention quickly and sharply. Beyond this, though, there are real benefits for filmmakers who would not normally make these kinds of films: narrative films gain greater depth of meaning when you allow nonnarrative passages to coexist with the main plot.

My kind of people?

Single-minded, realistic to the point of being existential and with a skin as tough as old boots, the promo director can seem like the one most likely to succeed. On promo shoots stakes are high, with expectations and pressure from artist and record label for ‘the big idea’, but the promo director takes delight in pushing their energies to the limit, taking pride in handing the client the movie on budget and on schedule. Nicknames are often variations on the ‘Terminator’ theme.

Figure 3.5 Advertising commercials demand production values as high as those seen in films, as in this shot from Neo’s ad for Nike, directed by Jake Knight.

Advertising commercial

As with the music video, this form is also a training ground for new filmmakers. The fast output of commercials and the need to say as much as possible in the shortest space of time means that the practitioner has to master the whole panoply of non-verbal signs and symbols — both from the world of film language and from that of universal symbols. All of this helps with your more conventional movies by allowing you to practise saying what you want to say in the shortest time and in the most economical way. As a form to practise with, the commercial asks you to work within a narrow brief, but it is this very constraint that often encourages creativity and the development of new solutions. New ways of sending video mean that ad directors are being recruited for phone viral movies (brief movies sent from friend to friend via phone or email) and short web ads too.

My kind of people?

Ad directors can be hard-nosed about what they do — constant and occasionally dispiriting pitching for jobs leaves its scars, but it is this thrill of the chase that drives them. Many have features in development and see ads as being dirty and fast, but they pay well. However, most directors of ads will only find that they have control over their careers just at the point when they leave it behind to start on the big feature. Not for the faint-hearted.

Weblink

http://www.clipland.com/index_tvc.shtml See the latest TV commercials online.

Polymedia

These are stylish, unusual pieces of work, often displaying new ways of combining animation, live action, text or still images, and pushing the creative possibilities of the medium to the limit. Meaning and content are less important than the visually arresting or innovative image, though these films tend to be in turns political, philosophical and entertaining. Practitioners make films that cross over into just about every form of the moving image, hence the ‘poly-’ prefix. They are like bees pollinating each form by taking elements of one into another and creating new works. This sort of work is at the front of the DV revolution, often mixing with scientists (Blast Theory), artists (The Light Surgeons), architects (Lynn Fox) and designers (Pliex). If you want to make fast progress while investigating the artistic potential of the medium and try an area that has no discernible rules yet, then this is for you.

Go to: Chapter 10:2 for more details on polymedia work.

My kind of people?

Increasingly, this sort of filmmaker works in animation, seeing the whole industry as part of an emerging ‘motion graphics’ field. Filmmakers of this kind don’t call themselves filmmakers at all, preferring terms that hint towards the convergence of video, graphics, animation and text. They are likely to have a sideline in VJ-ing and animation for ads, and like to evangelize their medium in workshops. In recent years they have come in from the cold — no longer submariners in the video world, their skills are wanted in TV and on the web. If you opt for this career expect to be poached by the omnipotent — and deep-pocketed — games industry, where you should ask for a raise on day one.

Weblinks

http://www.blasttheory.co.uk/ Art and science meet in this innovative group.

http://www.lynnfox.co.uk Watch Lynn Fox music promos online.

VJ (video jockey)

This form of video can be easily traced back to its birth — the dance music scene of the 1990s. The light shows quickly gave way to cut-up kung fu movies playing silently on a club wall. Later, cheaper video projectors and laptops enabled video artists to create a series of images that could be played alongside any music. But it is the ability to react instantly to changes in pace and rhythm that has let the VJ artist really enter the mainstream. With new developments in software, as a DJ plays a song, the VJ mixes spontaneously from a catalogue of prepared clips, using software to enable these clips to be cued and accessed without delay. Typically, more than one screen is used. New hardware has pushed VJs closer to the role of the DJ — the Pioneer DVD mixer allows a hands-on mixing of discs emulating the scratching of DJ-ing that makes it such a physical activity. There is a high turnover of clips; often, images last for only several frames or at most a second, but it is the repetition and mixing of these that VJ-ers use to add structure and give character to a piece rather than the content itself.

My kind of people?

The VJ is probably the most dextrous of all filmmakers but, like the projection artist, is reluctant to use the label filmmaker, preferring VJ or video artist. Films are called ‘visuals’ and artists often have a stage name or company name that is used as a pseudonym. Technical nerds but fashionable, VJs are amply rewarded at the higher levels of the field. A subtle shift in recent years means that the VJ is becoming more important than the DJ, so it is often refusenik DJs that enter the field. More often, though, these practitioners are coming from an art school background and are fascinated by images, shape, colour and form, seeing what they do as a kind of four-dimensional sculpture.

Weblink

http://www.vjcentral.com/ News and advice for VJ-ers from a UK-based site.

Projections

Many live music concerts now include large-scale video projections behind the band, utilizing everything that the medium can offer, from shaped projection screens to multiple, text-layered, spinning screens. Related to the music video form, these projections show images that relate to the ethos of the band in general, not necessarily for individual songs. Some bands employ projection artists as semidetached members of the band, developing the visual impact of the band on tour. Many music labels have felt a sharp reduction in sales due to file sharing and have decreased the funding they give to music promos in some countries. Many now see the live tour as the best marketing tool they have, with a captive audience for two hours or more, and seek to fill the screen with images that can tie in with other marketing tools and relate to CD artwork and T-shirts.

My kind of people?

Crucially, these people are artists first and filmmakers last. They may have entered this field through art school, having experimented with Super-8 and light shows. Technically, they have a wide range of skills and prefer to push the envelope wherever possible, experimenting with every aspect of the medium. Leaders in this field will be highly paid and sought after by musicians. As a sideline, they will also be doing video installations for galleries, touring as a VJ and getting involved in whatever no one else has done yet.

The Crunch

- Get to know what area of filmmaking you prefer — maybe it’s several areas.

- Feature films are just the tip of the film industry iceberg — other types of filmmaking are just as popular and far more achievable.

- Short productions help you develop more quickly.

- Try anything once — most forms are going to help you in whatever kind of film you prefer making.

- The more mistakes you make, the more you improve. Exercise your right to fail — at least you will do it your way.

- Invent, experiment, imitate, re-invent, do anything.

Project 2. In-camera edit

What this project is for: to learn about basic shooting and assembling sequences Time: allow a few hours

What this project is about

In this project, we are going to use the camera alone to construct a film, without the need to edit. The purpose is to show in a very short space of time what you can achieve on camera and get through some initial skills fast. Before you can visualize how your ideas will look on the screen, we need to find out how the camera sees the world. It is better to work this out now than when you are starting to shoot a larger production. This project enables you to learn quickly about camera use, taking short steps quickly.

What’s an in-camera edit?

The in-cam edit is a simple idea: it involves shooting each scene of a film, in the order in which it occurs. If it goes well then at the end of shooting you can take out the tape and play it as a finished film. This is the most basic method of making a film, but is an unexpectedly instructive way to learn about filmmaking and in a compressed way it takes you through the whole process of making a film, illustrating how the various elements interact. For example, while shooting this project you quickly realize that every movement of the camera counts, that you have to arrive at decisions fast and that there is little room for mistakes. One of the problems about video as a format is that it discourages decision making by allowing you to shoot just about everything and decide later what to use. The in-cam edit film asks you to work in a fast, concise way.

It also introduces a vital concept in a film: the sequencing of shots. This is an idea central to the whole filmmaking process, and the way in which you decide to order a sequence of scenes is best experienced for real, rather than as a paper exercise.

Finally, this method is a great morale booster; it takes you out of the still waters of paper development and into the fast lane, where you can discover quickly whether your ideas will work as you had intended. It also means that you can use this method for other films; an idea for a movie can be tried on for size before you go ahead and make it for real.

Stage 1: Find an idea

Although this film has a basic kind of narrative, it is simple enough to not lumber you with too much detailed storytelling. As with every project, simpler stories allow you much greater opportunities to focus on the way you are shooting the film, with less information to be conveyed.

As starting ideas, the following are examples of the mini-narratives you could choose:

- Escaping down a flight of stairs

- A short journey in a fast car

- A bad morning getting to work.

They each involve a direct progression in physical terms from A to B. These ideas may be simple but don’t dismiss them just yet. By keeping the story to a minimum they enable you to focus attention on the way you tell the narrative; the fun (and the difficulty) comes in how and where you point the camera, what scenes you choose to show and how much you show. The multitude of choices is what makes filming stimulating.

To develop the idea a little more, make a list of the shots you think you will need to convey the action.

Stage 2: Visualizing

Follow the guidelines in Chapter 4:7, ‘Visualizing your film’, about sketching ideas for shots. List the shots you think you would like to shoot on one side of a sheet of paper, and then draw images that could represent these adjacent to them.

Stage 3: Shooting

With an in-cam edit movie, you will take the first scene on your list and shoot it. It may be useful to do a couple of rehearsals if there is action or dialogue. During a rehearsal, remain looking at the scene through the camera; this encourages you to stay on the lookout for new, better ways of shooting it. If the scene goes wrong, just rewind and tape over with a better version, but do so as accurately as you can, hitching the new clip seamlessly onto the last one. Carry on like this until you have completed the whole film.

Tip If an object or actor is static, the camera should be moving. If an object or actor is moving, the camera should be static.

Technical glitches

Cameras have their quirks and one of these is the tendency for some to rewind a couple of seconds once you stop filming. Manufacturers have good intentions with this, as it is designed to prevent ‘snow’ caused by the blank tape showing through between shots, so it rewinds slightly to overlap each piece of film onto the next. If yours does this, simply work out how much it is rewinding and build this into the length of the shot. If your shot is going to last 10 seconds, make it last 10 plus the extra, so it ends where you wanted it.

Evaluation

It is worth going over a few points to see what has been gained. First, don’t worry if the final film differs often from the initial plans. A good film is not judged by how closely you have followed a pre-set path; if you have found better ways to shoot a scene while filming, use them. This is a good indication of the way your ideas are evolving about how to convey a scene, even during production.

1 Did you convey the brief plot adequately using the most economical shots? If you compress information to a smaller number of shots, the overall effect is more professional.

2 Did you manage to show more than one aspect, or view, of the action in a shot or did you find yourself having to constantly cut to close-ups to show what was going on? Maybe you moved the camera to new angles now and then to make the movie more interesting to watch.

3 Have you found it relatively easy to consider a number of different elements of filming simultaneously? Did you, for instance, find that you could think about the framing of the camera, the light on the subject and convey the right information at the same time?

4 The sequence of the shots is also important. Were you able to show the progression of events in order so it looked smooth and realistic?

5 You may also have noticed, when watching your movie later, that the length of each shot makes a difference about how the film works. It is very difficult to cut a shot correctly when using this sledgehammer approach to filmmaking, but you may have noticed how some of the more successful shots were the shorter ones. This is why cutting away to different views of the action is a useful technique.

In general, success for this film, however, is to be judged simply by whether you enjoyed making the film and found yourself with a short film that says what you wanted it to say. In a very short space of time, you have picked up some valuable skills in using the camera, telling a narrative and sequencing shots. And by planning on paper at the start, you help ensure that these areas work well before you pick up the camera.

2. How films work

The shortcut to making a film that lasts in people’s minds lies in understanding the nuts and bolts of movies — not just the technical side but the mechanics of how you make viewers see and feel what you want. The tools you have learnt and the conventions and rules you have picked up now need to come together to add up to more than just technology and skills. In a sense, learning about continuity, lighting or composition is like learning about the anatomy of filmmaking. This section takes us into what we could call the soul of filmmaking — the meanings that lie within. Understanding how this inner life works means that you stand to make your next movie an experience viewers won’t forget.

The tools

The basic building blocks in a film are:

- Image — what we see

- Sound — what we hear

- Space — what we think we see (perception)

- Time — when we think it happened.

Everything else in the movie is subservient to these basic elements. Story, plot and character are visible elements in the film, but are simply the result of the way the above are manipulated. If we look at how each of these elements are represented in your skills, we could identify them as:

- Image — camera framing, lighting, movement, colour

- Sound — diagetic sound (within the scene), non-diagetic sound (subjective, off camera), music

- Space — depth, focus, composition and sound

- Time — editing.

In different ways, each of the tools above are a way of expressing meaning in your film. Story and character are much less able to express meaning than they appear. An interesting way of throwing light on this is by looking at remakes, two films with identical stories but which have very different meanings through use of the camera, colour, symbolism and so on. The original Cape Fear (J. Lee Thompson, 1961) set up a moral narrative of how a decent family are targeted by a released convict, yet in Scorsese’s 1991 remake, certain changes are made that radically alter the meaning. The convict is given a semi-religious motivation, while the family are deceitful and self-destructive. The first movie places the sinner as the convict, while the second places the family — and crucially, the lawyer at the head of it — as the sinner while the convict is the sinned against.

So what exactly carries out the meaning side of the film? The answer is in the fact that every element carries it — it is not separate from the film but is integral to every part of it. Confused movies are ones where no thought has been given to what they actually mean, while resonant movies are the ones where there is very clear meaning. But this has nothing to do with what kind of meaning you opt for. Successful films don’t have to shout out an important message nor do they have to make the audience think something — they are not propaganda. In fact, many films today prefer to avoid sermons in favour of raising questions and ideas for us to take home and reflect on. Films such as Sideways (Alexander Payne, 2005), Donnie Darko (Richard Kelly, 2001), Far From Heaven (Todd Haynes, 2002) and In The Cut (Jane Campion, 2003) tend to nudge us towards outcomes rather than hand them to us on a plate.

We could refer to any emergence of the core themes and ideas of a film as signs. The devices that deliver these signs exist in layers surrounding the film. Some are easy to spot, others need a little work to uncover. Like forensic work at a crime scene, some signs are for rookies (the gun on the floor, the pool of blood) and others are for those who know how to look (the mismatched fingerprints on the trigger, the photos smashed on the mantelpiece). Like detectives, we try to uncover what happened and we look for a motive too — why it happened. Then we see how this makes us feel, what it tells us about people, life and the world today.

This hierarchy of signs is placed by the director so that we can experience the movie on different levels — it can be entertainment or it can be philosophy, depending on your choice. Sometimes, the philosophy side gets to be bigger than intended — for instance, in Hitchcock’s films, where we get to know as much about the psyche of the director as we do the plot. Elsewhere, a film can become more meaningful through its relation to the zeitgeist — for instance, with Terminator I and II, where we can track the changes in masculinity in society as Arnie is all Rambo-style machismo in the first movie but by the end of the decade is able to look after children and even weep with emotion. It’s easy to see why Kindergarten Cop was such an obvious next step. So, when watching a film, we need to look for signs at varying levels and look for others that may be attached later to the film.

Plot/story

Starting at the uppermost layer, we have the most visible elements of a film — the surface. This is like the shell of the film, containing the events that happen to make up the narrative. This outer surface is bigger than it needs to be — it contains not just the events and incidents that go together to make the plot, but also the entire fictional world that holds the plot. Signposts to this bigger world are strewn throughout so that we get a sense of where we are, what has happened to get us to this point, and what the norms and conventions are. Most films do this by relating the surface of the film to our own real world, and we imagine far more than is actually shown because it conforms to our experience. So, if we see two adults and two children eating together, we assume they are part of a family, because this is a construct we take from our world into the one on screen.

But films that don’t relate to our world are peculiar and unsettling. David Lynch’s second short film, The Grandmother (1971), creates an entirely imagined world in a dramatic departure from reality. This creates a surface or shell to the film that is unfamiliar and that straight away demands our forensic skills. We have to work hard to uncover even the most basic information. But it is rewarding if we stick with it, as we get to have profound and long-lasting ideas about life. These are films that people talk about long after they are over. This kind of surface has to draw in the viewer, however, just as much as the straight narrative does, but it does it by using other ways rather than recognition and identification. In Lynch’s case, he uses juxtaposition of real elements with the dreamlike and with unexpected moments of cruelty or violence; you can’t look away for too long as your curiosity gets the better of you.

Figure 3.6 A careful use of imagery enables filmmakers to create interest and meaning, as in this short, Northern Soul, from acclaimed director Shane Meadows.

In either case, the surface acts as a place where the events of the film are placed. Even if a viewer fails to understand the deeper parts of the film, they can’t fail to see what is actively in front of them, whether or not this corresponds to real life or not. What goes on below demands another kind of viewing, however.

Subtext

If we imagine each of the events on the surface happening above us, we could also imagine that each of them has an echo below the surface. In practice, this means that everything that happens above has a corresponding meaning below; a car door being slammed loudly doesn’t just mean that someone has shut the door, it also means the character is annoyed or angry. Scenes are not just descriptions of what happened (that is news reportage); they are imbued with meanings, all of which must lead back to the central ideas and purposes of the film. Subtext is about placing meaning at a micro level in the film so that each minor event adds something to the overall meaning of the film.

A knowledge of the craft of film means that the text (the surface) is not too heavy-handed in pointing us to the subtext. Subtle signs lead us in an unexpected way to what is below the surface through original scriptwriting, use of the camera or editing. Films tend to make the text explicit while the subtext is implicit, but in Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977), an amusing scene lays out both for us. We see the two main characters (played by Woody Allen and Diane Keaton) having a conversation, with the subtext shown in subtitles. So, a simple response to a query is subtitled as ‘Why did I say that? Now she will think I am stupid.’

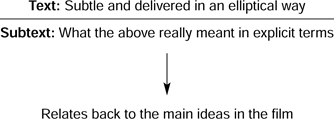

Subtexts offer an added layer of meaning which make each moment more stimulating. Crucially, the way this is manifested is like this:

As an example, we could take the scene in Star Wars when Leia, Solo and Skywalker are stuck in a corridor under stormtrooper fire.

In this example, the better the line or visual clue, the bigger the subtext can be.

Weblinks

http://www.pubinfo.vcu.edu/artweb/playwriting/subtext.html Concise university tutorial on subtext.

http://koreanfilm.org/trbic-oldboy.html Insightful essay on subtext in the Korean film Oldboy (2003).

http://thematrix101.com/contrib/azilleruelo_arfn.php Essay on subtext in The Matrix movies.

Theme

Further down beneath the micro-meaning that is subtext, we encounter the last stage that the director has total control over: the theme and ideas within the movie. The theme acts as an umbrella that brings together the individual micro-meaning of each scene. This doesn’t mean there is only room for one theme, however. Films today tend towards a multiplicity of meaning, rather than supplying just one dominant meaning. These can be less dogmatic, and more ambivalent, allowing the director to deal with conflicting meanings and opposing ideas. In straightforward genre films such as Armageddon, the theme works without conflicting ideas. In this film, the idea of heroism and of a simple working man sacrificing his life for humankind is undiluted.

However, in other films, the themes are no less transparent but require more thought. In The Virgin Suicides (Sofia Coppola, 1999), a series of suicides of young sisters leads us to think of themes such as the power of fundamentalist religion versus the need to grow freely into adulthood, or the strange voyeurism of the narrators who witness all but cannot intervene. And we also think about their paradoxical awe at the courage of the suicidal girls. None of it adds up to any coherent philosophy or rhetorical message, but it does give us lots to chew on after we leave the theatre.

For the filmmaker, the theme has to be approached in two ways for it to successfully make it onto the screen. First, it has to be identified early on as a core idea, so that it can become a motivating factor in each part of the script. To this extent, the themes need to be easily described, uncomplicated and to a degree universal as part of something we all relate to. But second, the filmmaker also needs to allow for themes to develop in unexpected ways. During development or even in shooting and editing, it is likely that other ideas will emerge that relate to the central ideas but were unforeseen. It is almost impossible to avoid this, as the collaborative process throws up new ideas, the lighting or camera presents a further side to the ideas, and editing reveals other variations. In this way, a filmmaker can allow themes and ideas to float and collide within the film.

To take another good example, Todd Haynes’s Far From Heaven (2002), mentioned earlier, uses a conventional appearance to throw up several ideas, all of which somehow go together but also collide in interesting ways. Set in 1957, it uses careful colour and design to suggest a technicolour period where values were uncomplicated and prejudices unchallenged, subliminally reminding us of film and TV of the time. Into this background, Cathy (Julianne Moore) uncovers the double life of her husband who is homosexual and, sensing the strict taboo on this subject in the suburban world she inhabits, can only confide in her black gardener, thereby breaking other taboos. In this movie, a series of ideas about whether the 1950s really were the golden age they appeared to be are revealed, colliding with others about the supposed tranquillity of the suburbs, which are portrayed as avenues of taboo and fear. Haynes then crosses all this with suggestions about film and TV itself, using clichés such as 1950s music and colour design to imply that we have continued to live in the world of I Love Lucy rather than the real one ever since.

In this level of understanding a movie, themes themselves often draw from the next level down in order to add complexity and — to a certain extent — interactivity.

Connotations: cultural and cinematic

This layer is the first to come from the audience rather than the filmmakers. Films can trigger references to parts of culture that we know already, that we bring with us to the theatre. This is like tapping into a grid of energy that can give the film extra life, where audiences hold reserves of interest in parts of culture that can be recognized in the film.

For several years, most audiences have been so sophisticated in their viewing habits and with their knowledge of films that it is now possible for a film to correspond less with the real world they inhabit than with the fictional world which other films have inhabited. The use of this has soared in recent years, perhaps more as a way of adding faux-depth to a film by alluding to a shared knowledge of culture, a safer bet in box-office terms than alluding to uncomfortable social truths. In some films this is more successful — Tarantino’s subtler allusions to French New Wave films in Pulp Fiction places an unlikely waif-like refugee from films like Jules et Jim or Breathless in a modern LA setting. This later developed into the use of Asian-style references in Kill Bill, not just in the use of local star actors and storylines, but also in the use of the retro opening credits sequence, where the words ‘Feature Presentation’ are placed in scratched and gaudy tones, mimicking a faulty projector in a downtown Hong Kong theatre. The point of all this is that we, the audience, can relate to these references. It flatters us and also dislocates the world of the film in a way which we used to describe as post-modern — like seeing a character from one soap enter another. Two worlds collide and it’s both amusing and unsettling.

Weblinks

http://www.livejournal.com/community/french_new_wave/ Discussion forum on French New Wave films.

http://www.greencine.com/static/primers/fnwave1.jsp Primer on the background of French New Wave films.

Animation studio Pixar have become master purveyors of this method in recent years in films like Shrek and Monsters Inc. In Shrek 2, for instance, the movie taunts its more grown-up peers in Hollywood by lifting iconic scenes from films like Titanic and Spider-Man, replaying them in a comic setting and thumbing its nose at their status. It is hard to imagine a more complicated set of signs within any work of art. Perhaps the most head-spinning example of this appears in Pixar’s Finding Nemo (2003). A shark tries to butt his way through a gap, suddenly shouting ‘Here’s Johnny!’ The reference was first to The Shining, where Jack Nicholson smashes his way through a door and says the same line, but also to the Johnny Carson TV show, which The Shining itself referred to.

Figure 3.7 In this still from Phil Dale’s commercial for Mini Cooper cars, references are made to previous sci-fi films, such as The War of the Worlds.

http://www.greencine.com/static/primers/fnwave1.jsp Latest news on Pixar’s post-modern empire.

Signs from wider culture

So these signs can be explicitly related to other films, or can be more subtle, drawing inspiration from an artwork rather than stealing it outright. When it is less obvious, it can be very rewarding, not least because not everyone in the audience will ‘get it’.

David Lynch playfully uses cultural references in his films, most often from the 1950s. In Mulholland Drive (2001), Lynch places a very stylized 1950s lead character named Betty (what else?) in modern Los Angeles. The story she inhabits is melodrama, the acting more so. Film noir elements are drawn in, using conventions of storytelling and characters that we recognize from literature and cinema. Music helps set the scene, with opening credits of the jitterbugging characters. Elsewhere, Baz Luhrmann exploits our knowledge of hit records in Moulin Rouge (2001). Top-hatted Parisian men dance to Nirvana’s ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ while a miniature Kylie Minogue, pop star and camp emblem, poses as a fairy. The aim is to collide our expectations by placing contradictory points of recognition in our minds. Whether this will work in much later years, when our store of cultural references has moved on (who’s Kylie?), remains the only weak point in this method.

Weblink

http://www.davidlynch.com/ News and information on David Lynch.

Connotations: political and social

This stratum of a film is a fascinating one for the filmmaker to tap into. The zeitgeist — or spirit of the time — is a powerful pool of fears, prejudices and hopes. As we will see in Chapter 9:2, the zeitgeist can be used to add depth and resonance to a film, by building in references to world events. This layer of meaning acts in the same way as lighting a set — it changes what we see by revealing it in different ways. Just as a room can be transformed by lighting it differently, so a situation can take on dramatic new meaning when placed in the context of world events. In this sense we literally see it in a new light.

In the same way, the zeitgeist can throw light on a seemingly innocent story and some of the most intriguing of these are ones where the director has not obviously set out to tap into our current fears. For instance, Shyamalan’s The Village (2004) is a spooky tale in the best tradition of Ray Bradbury. Looked at 20 years ago, or perhaps 20 years from now, and that is all it is. But when you factor in the zeitgeist it takes on a wholly different complexion. The film’s story concerns a group of people who fear the deadly creatures that are said to lie beyond its village borders, but which we later find out is a fiction to keep the inhabitants subject to its laws. The elders of the village have good reason to create the myth but find that it is ultimately impossible to maintain. On its release, it found an America in a similar state of fear — rightly or wrongly — of what lies ‘out there’. Similar questions were also being raised of its elders’ ways of keeping order in this climate of fear, albeit understandable after the tragedies of 9/11.

Weblinks

http://www.raybradbury.com/ More about the renowned sci-fi author.

http://www.futuremovies.co.uk/filmmaking.asp?ID 84 Interview with M. Night Shyamalan.

In this way, a film with prosaic genre starting points — and not especially original ones — became important for a time. In a more conscious attempt, Phillip Noyce’s Rabbit-Proof Fence touched a nerve in Australia’s soul-searching surrounding its treatments of Aborigines in the last century.

Weblink

http://www.iofilm.co.uk/feats/interviews/r/rabbit_proof_fence_2002.shtml Director of Rabbit-Proof Fence, Phillip Noyce, interviewed.

The golden age of all zeitgeist movies was the 1950s, coincidentally when fear was at its highest in a climate clouded by fear of atomic testing (see Them, The Incredible Shrinking Man et al.), Russian invasion (The War of the Worlds, Byron Haskin, 1953), creeping communism (Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Don Siegel, 1956), and world war (The Day the Earth Stood Still, Robert Wise, 1951). Science fiction proves time and again to be the most fertile ground for this kind of movie to flourish, seen again in later zeitgeists. Does Ripley’s discovery of the deadly alien growing inside her in Alien 3 echo the AIDS crisis of the late 1980s? The director David Fincher’s further fascination with the body in Seven suggests it was.

Weblink

http://www.awdsgn.com/Classes/WebI_Fall02/WebI-Final/JBusser/index.html Brief guide to sci-fi films of the 1950s.

Often blunt, the best of these signs manage to catch the prevailing winds of the zeitgeist rather than the temporary storms, preferring to ask deep questions that don’t go away rather than resort to cheap hits of passing fears.

In all of these layers there is a mix of both interpretation and intent. It is where the audience and the director join forces to inject meaning into a film. But the films with greatest interest are, perhaps, those where the director’s intent is aware of the audience’s interpretation and yet open to the possibility that a third element will enter the equation — the social and political climate of the era.

Film View

Five films to understand more about films:

The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (Peter Greenaway, 1989). Made at the end of the decade of strife in Thatcher’s Britain, nothing else quite presents such a horrific metaphor of a nation.

The Crowd (King Vidor, 1928). Silent masterpiece portraying the life of an immigrant in depression-hit America. The man is everyone, while the eponymous crowd is — what? Capitalism? The tide of human aspiration about to wash away?

Chinatown (Roman Polanski, 1974). There were lots of films that used paranoia and corruption as their theme in 1970s America, but few have the prescience of this. Is the drought in the film symbolizing our dwindling supplies of oil and the corruption surrounding the commodity?

Dawn of the Dead (George A. Romero, 1979). It’s not just highbrow films that can speak volumes about our world. In Romero’s first version of the film, there are some of the most anti-consumerist visions ever to be screened.

Uzak (Distant) (Nuri Bilge Ceylan, 2002). Remarkably detached filmmaking that brings deep dividends. The theme that slowly develops through a series of comic and tragic scenes is one of isolation against a backdrop of Istanbul embracing new technology and rejecting the past.

3. Film language and how to speak it

We talk about film as being like a language but actually it is very different to spoken language. In spoken language the word is the smallest unit and from there we build it into sentences, and these into paragraphs and so on. So do we assume that the shot is the smallest unit in what we call film language and that from here we build it into scenes, and scenes into movies? It isn’t that simple — and fortunately so because here lies the mystery of film. But if we can work out what actually makes up this complicated way of communicating we have a chance of mastering it — and perhaps adding a few new methods ourselves.

Let’s take a step back a few decades to when we used to call film a language. In the 1950s we used to read film manuals which told us that this or that shot would say this or that: a tilted camera meant that the subject was off-kilter in some way. The way film was taught back then was like having an alphabet of how to shoot — you went on set, took out your ABC and shot exactly like it said, using the same device again when necessary.

By the 1960s, however, we started to think very differently about all sorts of language, largely as a result of French theorists like Saussure. Further ground-breaking work was done by his compatriot Christian Metz in looking more widely at all sorts of codes at work in a movie, not just the obvious ones of shots and camera angle. Metz talked about the multiplicity of signs that unfold in each shot, so that instead of a film language we have something like a cacophony. So editing had its own codes, as did the story, as did the setting and the use of the camera, sound, light and colour. All of these could potentially carry meaning and could be ‘read’ simultaneously. What’s more, they borrowed many of the ways of doing this from other art forms, which themselves later borrowed them back (for instance, in the work of Cindy Sherman, photographer).

Weblink

http://www.cindysherman.com/ Information and gallery of the artist.

Syntax

The syntax of a movie could be said to combine all the elements of a film. But as we have seen, it doesn’t lie in the use of the camera or the way a shot is edited, but in the space created by the pull of these two opposing forces in a film: the illusion of space (the images) and the illusion of time (editing).

The image consists of elements such as:

- Camera angle — how we view something changes what we think of it

- Colour — the connotations of certain colours affect meaning

- Shape — certain shapes in the composition can affect how we view a shot

- Lighting — elements can be highlighted and brought to our attention

- Depth and focus — where elements within the frame are placed affects how we view them; which is in focus further affects this.

Connecting these are the three-dimensional effects created by the camera in space by the movements of the camera or of its subject. Elements within the frame are altered depending on which lens is used (wide-angle, close-up) and by panning or tracking.

If we move away from this syntactic view of a shot we can see another set of elements waiting to add further meaning. As soon as we place one shot next to another — we edit the scene — then we include time in the equation. Which events are placed next to each other, whether we go backwards or forwards in time, and which events are highlighted and dwelt on, all affect the meaning of the film extensively.

In a sense, a film such as Memento (Christopher Nolan) is almost devoid of meaning when its editing conceit is taken away. If the movie is viewed ‘the right way’, as in the DVD version option, it is relegated to mere genre movie. Similarly, Amores Perros (Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu) would be rendered an almost pointless soap opera if the events it told were placed chronologically or in parallel. Instead, their convergence to a central point in the middle of the film imitates the car crash that unites the various stories in a literal way at a literal crossroads.

Added to this two-way pull between space and time is a third force, the audience. This, however, is an unstable and unpredictable force that is shaped by locally shared perceptions (black is the colour of mourning in the west, while white denotes this in the east) and further skewed by personal perceptions. Perception is such a nebulous concept it is tempting for the filmmaker to drop it from the start. It is like trying to work out what to wear to an office party three years from now — you don’t know who is going to be there, what your clothes will say about you then, nor what the climate will be. For most filmmakers, audience perception is seen as inhibiting the creative processes, reducing authenticity by forcing them to consider someone else’s imagination outside their own.

But it can become liberating to consider perceptions. Once the film has left the filmmaker’s hands and goes to the audience it then attracts layers of meaning and connotations brought along by each viewer. It snowballs, but while retaining the central meanings intended by the director. To ensure this happens, that the film grows in meaning, the filmmaker must include enough ‘moments of meaning’ through camera, symbol, motif, editing, sound and the other tools of the craft to kick-start the process.

Ways of conveying meaning

The main carriers of meaning — as detailed in the chapter on form and symbolism — are the many signs that populate a film. But we can be more specific about what these are, breaking them into two sorts:

1 Signs — where something is

2 Symbols — where something means other than what it is.

The first category is easy — it is a set of signs that we all recognize immediately. A building with a garden and containing a family is a house. Symbols go a stage further by including other visual clues that apply a meaning to what we see. So, the same building with drawn curtains, smashed windows, accompanied by tense music implies a certain sort of family, perhaps suffering. The signs it uses to convey this are something we can all agree on and recognize almost universally.

Symbolism

A symbol is a sign, a carrier of meaning in typically visual form, and is one of the most effective ways for depth of meaning to manifest itself. Its visual nature means that what it represents is not always easily translated into words and its reception by the viewer may vary, according to culture and experience. This does not undermine the symbol, but may actually lend it longevity.

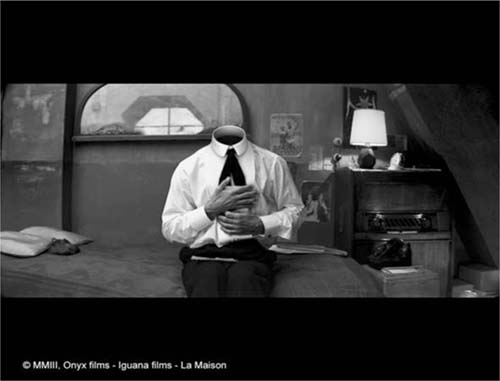

Figure 3.8 Using dreamlike imagery, Juan Solanas’s Man Without a Head was acclaimed at film festivals.

Being able to notice a symbol is less easy than defining it. In films there is such a wealth of visual material contained in every shot that we have to exercise some criteria if we are to distinguish a visual element which alludes to something else from that which is merely functional.

Where are symbols?

The key to doing this is in having some understanding of what a film’s content is — often invoked in the film’s first passages, but further clarified in the title, or in advance publicity. In Mike Leigh’s Secrets and Lies (1995), the title gives us a clear idea of the theme that resides within the plot. From the outset, it is clear that plot is going to be less important than the themes and ideas in the movie. We become interested in what happens to the characters, but what we remember when we leave the theatre is the meditation on racism and family secrets at the heart of the film. Independence Day (1996) also tries to do this, with a title alluding to more than the simple events of the plot. It wants to be a film about big issues of patriotism and nationhood, but it fails to deliver further symbolism to satisfy its claims. Then, at the end, it has to hurry to get across its deeper aims with a scene of Bill Pullman’s speech as President of the triumphant United States.

The key to finding symbols in a film lies in their being repeated often. We are led to their existence through particular composition or lighting, or can be reminded of them through sounds or musical motifs. A skilful director will place symbols discreetly but will reinforce them through using elements of the script. In Jane Campion’s In The Cut, the symbolic lighthouse seen frequently in the film may refer to the location where the killer lurks, the literary lighthouse in Virginia Woolf’s book, and perhaps hints at male power.

Weblink

http://www.symbols.net/ Graphics and explanation of literal symbols in history.

Know about the director

As well as the title of a film, we can find out more evidence for where to find symbols by looking to other examples by the same director, or other films within the same genre.

When watching Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963), for example, we see broken crockery hanging on the dresser before we see the horror of the victim of a bird attack. Earlier in the film, after a previous bird attack, the camera lingered on other broken crockery and after a couple of these shots we can’t fail to note it. Hitchcock has said that, for him, broken crockery represented disruption in family life, so we recognize allusions to his own experiences of family life and in turn our own. This symbol stretches beyond the original intention of creating suspense and preparing us for the appearance of the victim; it ripples outwards to the audience’s own experiences. But we do not necessarily need to have prior knowledge of Hitchcock’s own hang-ups here; by presenting this symbol repeatedly, we can start to look for it and it becomes a signifier of more than it would elsewhere. We add it to our canon of symbols and take it to our next Hitchcock experience.

Symbolism rests on more than just props. It can exist in any tangible object or set of objects within a film, and even as an unseen object. In Kubrick’s The Shining, for example, the maze into which the deranged Jack enters parallels the labyrinthine layout of the hotel, and through careful presentation of this element of the set, we are led towards seeing it as a parallel of Jack’s mind (for example, in a scene in which Jack looks at a model of the maze, or when we see him encounter different incidents in the hotel that his wife cannot be a part of — see Project 9 on subtext in the movies). When we later see him lose his way within the real hotel maze, the dramatic effect is magnified many times. The symbolism of these places, quietly generated throughout the film, and their resemblance to Jack’s mind shifts this scene to one on a much higher plane, of Jack finally losing his way psychologically, of being imprisoned within his own mind — of finally losing his sanity.

Motif

A motif, according to a dictionary definition, is a dominating theme, but also a recurring design. In textile design, a motif would be a shape or design element that recurs throughout the whole design, carrying more of what the design is about than other parts, and its recurrence would confirm this. This helps us to understand how it is applied in the moving image, where a motif is also a recurring visual element that carries meaning.

Motifs are closely connected with symbols. Where symbols are immediate carriers of meaning, a motif can amplify this meaning several times over the course of a film, relating it closely to the main ideas motivating the film. In a sense, motifs are the parent of symbols and symbols are the parent of subtext; the resonance of their meaning becomes smaller as you move down one to the other.

To work effectively, motifs must be a tangible part of a film. In other words, they have to be something that we can see and may often be a central part of the plot. It will become a bearer of a film’s underlying theme and, with skill on the part of the director, will be both specific enough to relate to the film’s purpose, but broad enough to have some relation to wider experience.

Case study

In mainstream films, motif is perhaps less concerned with broadening a theme than with making it more explicit for the audience so that it is easier to get a grasp of the main message in the film. For instance, there is a difference between the eye motif in Don’t Look Now (Nic Roeg, 1973) and the mountain motif in Close Encounters of the Third Kind (Steven Spielberg, 1977).

In Close Encounters, a recurring image of a flat-peak mountain is seen throughout the first half of the movie, serving to heighten the moment when Richard Dreyfuss finally sees it for real. But at no point is the motif held up to be anything greater than what it is — a plot device — and any further investigation is self-serving. With Roeg’s example, however, the result of our delving further into the motif is rewarding and reveals much more about the film, but also stretches outside its filmic boundaries to offer a more reflective consideration of the issues raised by the film. Let’s take one of those examples in more detail.

Motif in Don’t Look Now

In Don’t Look Now, we are primed to look for and reflect upon images outside of the immediate action. Roeg’s skilful and systematic use of montage breaks down our reliance on the script and our need to maintain a chronological flow to the story. We start to decipher images which appear almost without reason and, together with our need to construct meaning out of what we see, we start to make connections. In other words, we infuse meaning into objects or images that normally would pass us by. Roeg makes sure, however, that this is no wild goose chase, but is actually pertinent to the scenes we see unfolding.

In many parts of Don’t Look Now, vision is a part of the action. There are references to sight, seeing, second sight, blindness and so on. In the extraordinary opening montage, we see Donald Sutherland and Julie Christie enjoying a typical Sunday afternoon, oblivious (they can’t see) to the danger of their small daughter at the edge of a nearby river. Sutherland then runs out of the house as if he has heard something within (has he got second sight?), but is too late to save the child. At the film’s terrifying closing montage, his implied or partial second sight and his curiosity in terms of physical sight — to see the strange figure he glimpses throughout the film — leads him to disaster.

Between these two montage points, various elements reinforce the eye motif: the medium who claims to have seen the dead girl is herself physically blind and we get occasional shots of her eyes when Sutherland is in danger. The overwhelming sense in the film is of seeing and not seeing, both metaphorically and physically. Shots that seem to momentarily throw our understanding of the plot in fact serve to clarify the film’s meaning. The net result of these tangential moments is only realized, however, by Roeg breaking the rules of temporal and spatial reality, enabling us to see everything within the film as potentially important and potentially symbolic — rather than doggedly following the plot.

So what?

Where does all this leave the filmmaker? Without doubt, symbolism and motif can elevate a film when deployed sensitively. They can help make it more than just the sum of its separate clips, lending the film an inner life and helping to convey far more profound ideas than can be contained within a story. Nor is it restricted to any particular genre; a film that is not necessarily setting out to be insightful can benefit from the placing of elements within the film which hint at bigger ideas.