6 Production aesthetics

1. Better looking films

You’ve spent a while looking at how to stretch the potential of your camera without spending any cash on the film itself. Now you need to look at what kind of ‘feel’ you want in your film and how the overall look of it can be achieved. Working with a small budget, you may not be able to rely on well-known actors or sets to make your film stand out from the competition, so you need to become more confident about what you can achieve with those tools that don’t cost anything: what the camera sees.

Make your camera work harder, make your film look better

The aim of this section is to go through some of the basics of getting the most from the camera; how to get the right shots and how to find those elusive, special shots that will make your film rise above the rest. But as well as knowing the shortcuts to getting these kinds of shots, we need to look at how you can depict something in a professional way, to industry standards. This doesn’t mean you are going to produce dull, uninspiring images; we are just going to concentrate on learning a few rules in camerawork so that later you can feel free to break them.

Use the rules and bend them

It may seem that if you know what kind of film you want to make you shouldn’t need to know how other people work. It’s true that no one knows better than you what kind of film you want, but this next step is not about copying how other filmmakers do it, it is about learning how to get your preferred shots more quickly. When you know how a certain shot is often filmed it gives you a starting point — you can either go with the norm or reject it. It can make you think faster. Furthermore, if you find yourself working with a crew of other people also committed to making films, they will expect you to know what works when filming — and what does not.

Conveying mood

Mood is a nebulous concept, but to attempt some definition, we could say that it is the integration of the various style elements of a film with the core theme of that film. Lighting, music and camera angle are the main tools behind the camera helping you to achieve this. It may shift throughout the film, but a pervasive atmosphere will dominate if the film is to be coherent and consistent. Mood is something that is evoked rather than described explicitly, so you have to rely on subtle methods to add a particular slant to a scene. Being able to manipulate mood is useful because it enables you to specify what sort of emotions are dominating a scene and how we as the audience should interpret it.

Let’s suppose you want to shoot a scene in a drama. There is a character who is afraid of something; he is in a dark room and is apprehensive about something that is about to happen. You decide you want lots of tension and you want to increase the sense of drama. Now your job as a director is to shoot that scene in the most effective way, conveying clearly the atmosphere evoked by this character in this room in this situation. If you know some of the ways other people have produced tension or fear in a shot, then it immediately gives you something to start with. When you know the rules you then start adding something of yourself to them; indeed, your own personal style is the way you respond to the rules and in what particular way you break, bend or stick with them. So, in this instance, you may use lighting with higher contrast and with the camera may use close-ups to exaggerate the facial expressions of the actor, or long, wide shots to emphasize the sense of isolation and vulnerability of the character in the room.

Composition

Let’s concentrate now just on what the camera can achieve in showing the plot and conveying mood. We can look at how shots are more effective if you think about how you are arranging the objects within the frame. The position and angle you select for the camera relative to the subject and its surroundings is called the ‘composition’.

Figure 6.1 Setting up a well-composed shot takes time. In this production shot, director Carl Tibbets tries to use the mirror to give pictorial interest.

Composition in filmmaking has developed mainly from the ideas of painters in Renaissance Europe; many cinematographers will freely admit to being inspired by great paintings of this time. But the great filmmaker Eisenstein has suggested that we need framing for all our art because we tend to look at the world through windows.

Tip Try looking at Renaissance works by Masaccio and Giotto to see where classic, epic staging originates, or look at the sumptuous attention to light by northern Renaissance artists such as Jan van Eyck or, later, Vermeer.

Tip Sergei Eisenstein is credited with having established some of the fundamental ideas behind montage in his ground-breaking films such as Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Strike (1924).

Composition helps a low budget

Going back to our scared-man-in-the-room scene above, it is quite likely your budget averages your monthly disposable income and you definitely can’t stretch to dry ice or a specially composed score. The lower your budget, the more you must try to get your camera to work harder. It’s no coincidence that directors making their debut feature will display quite high levels of ingenuity with the camera, showing off a number of different compositions to make up for a lack of expensive props or effects to point the camera at.

But don’t show everything

You are also going to rely on the audience to imagine some images. A good director would not have to display all the action or spell out the whole narrative and will use imaginative compositions to suggest and evoke, allowing the audience to fill in the gaps. But this sort of filming is quicker and more successful with a good grasp of the basic rules. If you watch The Haunting(Robert Wise, 1963), you can see how a small budget was somehow irrelevant. The film’s scariest moments rely on clever composition, pointing the camera at a certain shape, shadow or object and at a certain angle to give a feeling of unease. As if to prove the theory that what we don’t see is scarier than what is spelled out for us, the remade film in 1999 (directed by Jan De Bont) made much of the implicit horror explicit and was widely condemned as not scary enough.

Basic starting points in composition

- The clarity of the objects in view

- The amount that is not in view

- The use of shapes to denote particular theme or mood

- The angle of the camera.

Within this there are certain kinds of composition that are more suited to certain situations. The eminent cinematographer Nestor Almendros used a lifetime of experience to describe the following principles:

- Horizontal lines suggest serenity and calm

- Vertical lines denote strength or authority

- Diagonal lines suggest action or movement

- Curved lines suggest fluidity and sensuality

- Moving a camera forward to enter a scene suggests ‘bringing the audience into the heart of the narrative’

- The opposite movement, away from a scene, is often used as a way of ending a film.

(A Man with a Camera, Faber & Faber, 1982, p. 14.)

Placing action in the viewfinder

To get to grips with composition, start by looking at the way you use the whole. Try a short exercise: get a sheet of paper the same shape as the screen you intend to work with.

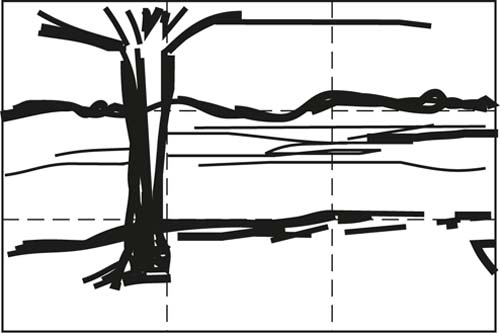

Figure 6.2 Use the division of thirds on the paper to place objects within the composition. ‘Hooking’ them onto the verticals or horizontals gives rise to depth in the image.

The shape is what is called the ‘aspect ratio’ of your screen. Aspect ratio refers to the height and width of the screen. The common standard for European television is 16:9. Most filmmakers like to work on a slightly rectangular screen because, in terms of composition, it is easier to get a more interesting arrangement than using a square. This shape has evolved over time as one which will most help you in finding a good arrangement.

An A4 sheet of paper is as good a shape as any to start. Fold it into thirds both horizontally and vertically so you have nine rectangles. Try to imagine the sheet as your viewfinder on the camera and look at any shots you have so far on your camera, noticing in which rectangle the action tends to be in each scene.

Lazy parts of the screen

If we number the rectangles from 1 to 9 across the rows, you might find that most of the action in your footage takes place in the fifth box — the centre of the screen. Whether you are shooting a very still scene such as a conversation, or a running chase scene, it is common to find that the focus of attention is in the middle and all the other boxes are unused. This is easy to shoot — you just place the subject in the centre of the screen and stand back — but it makes for bad composition. It’s predictable and boring, but your job is to grab an audience’s attention as much as possible, even in quiet scenes. Have a look at some of your own images on your films: is box no. 5 doing all the work or are the others pulling their weight too? To encourage you to find new camera angles, keep moving the camera around until the action is spread throughout the nine boxes. Every box doesn’t have to be used in each shot, but there should be a spread throughout the film. After trying this method for a while you will soon find that you naturally want to compose the frame rather than just shooting into the middle of it.

You can be aware of this during the planning stage, so that when you do storyboards you can stop the bad ones in their tracks and redo that frame. But if you find that you have poor compositions when you are actually filming you need to rectify it on location, under pressure. If you have an LCD viewfinder you could place a sheet of clear acetate with a grid over it to keep a check on how you are dividing up the screen.

To assess how you use the screen, you could shoot a simple scene (such as making a cup of coffee), but avoid putting the action in box no. 5, in the middle. Avoid the tendency to depict the action squarely in the centre and try constantly to be aware of the whole screen. Although you would not want to avoid the centre box all the time when making a movie, this exercise of abstaining from the centre does force you to give added weight to other areas of the screen.

You can then try watching feature films and notice how much of the screen is used. You might start to notice some of the conventions that filmmakers use. For example, placing a character to the edge of the screen can heighten the dramatic content of that scene and tilting it can give a sense of unease. Don’t forget, however, that there are many times when a centrally framed shot is just right for your film. The director Stanley Kubrick made this kind of shot his trademark, as he found it gave some shots a kind of claustrophobic feel.

Film View

Watch Paths of Glory (1957), Stanley Kubrick’s film set in World War One, to see how a one-point perspective shot can work as he takes us around the trenches. In other Kubrick films we often see shots where we look down a corridor or narrow space. The Shining (1980) is full of long corridors with unknown horrors waiting around the corner. In the earlier Killer’s Kiss we see a similar clip of moving down a narrow street, as the main character has a nightmare.

Composition dividing lines

With a bit of practice you may now see separate areas when you look through the viewfinder, dividing up the image. But the four dividing lines that separate the boxes can also be very useful. You can start to use these as ‘hooks’ to peg your actors or action on. Let’s use an example of, for instance, a simple dialogue between two people. When you watch other films you start to notice the most common composition for placing the face within the frame. Heads can be very difficult to place because you need to make sure the mouth is visible all the time and the eyes are prominent. Try putting the eyes on the upper line (see Figure 6.2) - don’t worry about how much of the forehead you have to lose — then place the nose on either of the vertical lines.

Figure 6.3 The right framing can create an atmosphere out of the least inspiring places. In this case, director Jake Knight shot an underground car park as part of his short, B3.

Figure 6.4 In this image from director Jo Price, the two actors are placed to the left, in line with the golden section, leaving room for depth in the background.

Feel free to break this rule, but it is a good place to start for a well-composed shot. Avoiding overusing the centre of the frame works because it moves the focus of attention away from the place where we lazily and automatically want to look and allows other objects or people to occupy the spaces left over, adding more interest to the film.

The same goes for landscape shots: place the horizon on one of the horizontal lines and any distinguishing features such as trees or a building on the verticals. You are making the audience look at different parts of the screen and this makes for a less predictable experience. If you make the audience look around the screen constantly it starts to work in your favour, as they will then start noticing everything in the shot. Of course, if it is done badly it is distracting, but every kind of filmmaker tries to make his or her film more interesting to look at. In fact, now that Hollywood has discovered computergenerated images, directors can also achieve unusual, daring shots in large-scale action sequences such as the extraordinary city sweeps in Spider-Man 2 (Sam Raimi, 2004).

Using depth in your shots

We have looked at how to use dividing lines to help you get good compositions. One of the things created by these compositions is something called ‘depth’. Don’t confuse it with meanings in your film; this is pictorial depth. Basically, depth is your way of inviting the audience into a scene. If you follow the ideas in the last chapter about dividing up the screen you will almost certainly have put some depth into the shot without trying. Depth is achieved where one object or person is close to the camera and something else is further away. The space you create in the middle is called depth. It is disarmingly simple, but if you are conscious of it when setting up your camera then you are going to get a much higher success rate in terms of getting great-looking shots. Once you’ve understood it you can then start to use it to your advantage, putting greater depth where you want a more dramatic scene.

Figure 6.5 John Sealey’s short film, The Greatest Escape, raises fascinating issues of race while dealing with the Second World War.

Using tripods for composition

The tripod is a very useful, essential piece of equipment, but it is expensive. It can be very restrictive, but on balance it’s probably a good idea to have some sort of support for the camera occasionally. If the cost puts you off, try a mini-tripod, which is a shorter and smaller version but does need a tabletop or other surface to rest on. Some wildlife filmmakers use a beanbag on which to rest the camera, as this enables the user to move quickly to various camera angles and doesn’t require a flat surface. It also helps you to get a range of steady shots without having to fumble around altering the tripod constantly. Alternatively, you could get rid of the tripod altogether. There is a school of thought which says that the tripod stops your film from having vitality and spontaneity. Filmmaker Robert Rodriguez suggests that, ‘If you have a tripod you are going to leave the camera stuck on it. It looks nice — and your film is going to look dead.’ Good advice for the lazy filmmaker, but remember also that filming without a tripod requires skill. Keep the camera under control, giving us a view of the action from one viewpoint, just as if it is another actor, watching rather than participating in the action. Feel free to alter this viewpoint throughout the scene.

Tip Watch out for ‘hosepiping’, which occurs when the filmmaker waves the camera around without providing the audience with a firm place from which to view the action. Apparently, when watching The Blair Witch Project, more people felt ill from the violently moving camera than from the violent events it showed us.

Tripods can inhibit good composition

The idea goes that as soon as you have placed your camera on a tripod you effectively close the decisionmaking process, removing the possibility of other ideas coming up which could improve a scene. So, if you are using camera support, you need to be certain that you have got the right shot before you get out the tripod. Try setting the composition to begin with without any support, looking continually through the lens to make sure you try out every conceivable angle and then, when you are sure you have found the shot that works best for you, set it on a tripod. This method ensures that the camera angle does not have to compromise to suit the tripod’s limitations.

Tip There are many other filmmakers who reject camera support. The Danish group Dogme believes that any use of tripods adds further layers of artificiality to a film and takes its audience one step further removed from it.

Finding and using unexpected shots

It is reasonable to suppose that if you have planned a film properly you should never need to find extra shots. Many filmmakers, however, believe that the combined energy and input of a lot of people on set can throw up unforeseen opportunities for quite unexpected shots. It is already accepted that actors may ad lib in a scene, only to find that the director keeps their off-the-cuff lines and removes the written part of the script. It is the same with filmmaking; you have to be aware that there are many shots you are not getting because you are sticking rigidly to your storyboard.

It is poor practice to shoot endless amounts of footage that you have then to trawl through in postproduction, but try to strike a balance between letting new ideas enter into your plans while shooting and sticking to the plans worked out earlier. Many first films look too precious in their choice of footage, as if each frame was a life and death decision, while some of the most captivating are those that let less well-considered shots into the final edit. In writing terms this would be the equivalent of communicating solely in formal language, as in legal small print, where each sentence is perfectly chosen and in perfect English. But less formal language can be more affecting sometimes and may enable you to communicate more directly to the audience. In both the editing and shooting stages, look for and keep footage that veers from your plans. Let these ‘slang’ shots enter into the language of the movie later.

Spare shots

There is another good reason for allowing more footage to be gathered than first intended. When we look at editing in Chapter 8:1, you will see how useful it is to have spare shots with which to patch over parts of a scene now and then to add interest and keep the audience watching. The kind of shots that turn up when you are simply experimenting to find the right angle or lighting effect can add variety and spark to a film.

What kind of shots?

Inevitably, preparation work is capable of preparing you too well; you end up knowing exactly what you want and will probably end up making a good, honest movie. But filmmaking remains an art form as well and as such needs to have some allowance made for the unexpected during shooting. It is this that marks the line between the average, workaday movie and the one that grabs the audience and makes the movie a more dynamic experience. The kind of shots you can use to sprinkle over the movie later are the ones that you would usually discard, either because they don’t fit in with the rest of the scene or because they have some slight fault in them. You might stumble across some of the most unusual compositions when you have occasionally departed from your plans and might have considered the result a mistake. But when you get to edit the movie later, revisit these unwanted parts of your footage tapes and give them a chance.

Let’s take our earlier example of a straightforward scene with dialogue between two characters. Filming this scene will be relatively easy as you have to show only two actors, but after a minute or so you could start inserting the occasional shot of the two from a distance, or a shot taken in close-up as the actors were rehearsing earlier. However, don’t show faces on these ‘patched’ shots if the actors are speaking, as the new shots would be out of sync with the rest of the scene. Try to film shots of the actors’ hands moving; this can emphasize drama in certain scenes and is vital for covering up the join between two takes of the same scene.

In American Grafitti (1973), George Lucas made his first full-length feature by filming virtually everything from every angle and leaving decisions about how the film would look to the editing stage. The result is a drama that has the realism of a fly-on-the-wall documentary.

Figure 6.6 In this still from Amma Asante’s A Way of Life (2004) the characters stride towards the audience - and the action.

Figure 6.7 In this still from Lisa Gornick’s Do I Love You?, the main character is framed by two unseen hands and we are left with the impression that plans are being made for her.

Camera language

Camera language is something that is going to apply as much to narrative films as to non-fiction work. We have seen what good composition can do for a film, but here we need to know how the camera can convey certain meanings and use these as part of a repertoire of shots to say what you want without having to use words. Take a health check, however, on any slide into thinking that camera language is like verbal language. In film, there are so many other variables which alter the meaning of a shot that it is impossible to ascribe definite meaning to a certain sort of frame, track or tilt. Just use the ideas below as starting points to which you can add more meaning in your own way.

Camera framing

Camera language is an important way of conveying your ideas. Subtle changes in camera angle, height or movement all affect what you are showing. Over time, a broad vocabulary has been established in which certain angles of shot correspond to certain feelings or views of a subject. Much of this has been developed by the early masters of narrative cinema, such as Hitchcock. Being aware of this language is useful in being able to adhere to, or subvert, convention.

For example:

- Close-up shot. This kind of shot will often raise the dramatic tension in a scene. It evokes intimacy and sensuality, but also suggests enclosure or claustrophobia. Directing the viewer’s attention so tightly to one aspect of a scene also makes clear your own interpretation on the subject.

- Tilt. In this shot, the camera is tilted so that the viewer sees the world at an angle. The general effect is to suggest imbalance, a situation not quite right, a character unable to find his bearings. A slight tilt of perhaps 70 degrees (where 90 degrees is vertical) will give a more subtle indication of this state, while more exaggerated angles increase this feeling.

- Camera looking down on the subject. This can suggest vulnerability in the subject. It indicates that the viewer is higher than the subject and is therefore more powerful than the subject.

- Camera looking up at the subject. As the reverse of the above, this shot can suggest that the subject holds power by placing us below.

Camera language is similar to spoken languages in that it evolves and is a result of its usage rather than being formulated in advance and adhered to. Certain devices are seen to work but change considerably over the years, partly as a result of the increased sophistication of the audience. So-called ‘Hollywood grammar’, popular in the middle of the twentieth century, has evolved so far as to be unrecognizable.

Multiple meanings in camera language

As with narrative film, non-fiction film takes full advantage of the uses this kind of camera language brings and enjoys subverting one sign with another. For example, a happy, optimistic image can be altered slightly, suggesting some underlying unhappiness by slowly withdrawing the camera from the subject to reveal an isolated subject. One way to illustrate this is to look at spoken language. When we listen to someone, we take on board what they say but also watch the way they move their arms, their whole body language. Interesting juxtapositions can be made when one form of communication contradicts the other.

Film View

Some films use cinematography as a significant way of conveying meaning. In Paris, Texas (Wim Wenders, 1984) every scene seems like there is an extra actor present - the landscape. It carries the weight of the theme of alienation and loss like an Oscar winner, but only does so because of the judgement of the cinematographer. Many filmmakers use the American landscape to show similar themes, focusing on the deserts and midwestern flatlands to throw into relief the feelings of the protagonists. See also Terrence Malick’s Badlands (1974), Napoleon Dynamite (2004) and David Lynch’s Wild at Heart (1990). Australian landscape develops similar themes in films such as The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (Stephan Elliot, 1994), Walkabout (Nic Roeg, 1970) and Rabbit-Proof Fence (Phillip Noyce, 2003).

How we read images

Another factor is that the image the camera gives us is read as both a mental and optical phenomenon, hitting the brain in two ways. When we see an image, we read it as (1) a simple array of patterns on a mental or cognitive level and (2) as a cultural reference point. Take, for example, a shot where a character is standing in a doorway with strong light on the face, the door framed by black shadow. We can track how we perceive this image by focusing on both the mental and optical.

Optically, we see the figure before we see the blackness, and we respond strongly to the impact of the bright light shining on the face and the high contrast of black and white. We feel a need to decipher it and will pursue whatever little information we are given, and yet our interpretation of what we decide the image is saying is influenced by the impact of the optical effect the image has on us. This is why some camera compositions and lighting effects are particularly useful for the filmmaker.

But the image of the figure in the doorway will strike us for other reasons, on a cultural level. We have preconceived ideas regarding shadow and others regarding faces lit in the darkness. An air of mystery may surround it, or a sense of something spiritual or perhaps menacing. The face may also have a particular expression, drawing in our memories and feelings about the particular emotion we are seeing; one section of the human brain has the sole function of analysing every other human face we see, for recognition of the familiar tribe or family, so we also search for anything that resembles a face, also linking into the optical view of the image. Our response is determined by our culture, affecting the significance of certain signs in the image.

It is the combination of both cultural and optical that work together to come up with a single idea of what is being signified. The signifier is nearly always visual, while the signified is necessarily a mental picture.

When you frame a shot, you are therefore setting up a range of responses in the viewer. Being able to control all of these responses is outside anyone’s reach, but it is possible to manipulate response to a certain degree.

Tip For more reading about the area of visual perception and art, try art theory classic The Hidden Order of Art, by Anton Ehrenzweig.

The Crunch

- Make your films look good

- Get to know the rules of composition

- Know when to use the conventional approach and when to try something new

- Good composition can give a low-budget film a high-budget look

- Be aware of the whole screen when shooting

- Use composition to allow for pictorial depth

- Try unexpected shots, found during bad takes

- Show you are a master of conventional filmmaking and a master of doing it your own way.

Project 14. Close-ups

What this project is for: to improve camera technique

Time: allow a day to plan, another to shoot and two to edit

What this project is about

This project concentrates on the use of the camera and how it can help you in conveying narrative. In this project we will be making a straightforward movie using a simple plot, but will be doing it with a particular restriction: the entire film will be filmed using close-up shots only.

If narrative is concerned with information then the purpose in working with close-ups is to focus attention on what is important in a scene and prioritize the various elements within. In conveying the story you develop, you should be able to see in the final film a positive linear progression of the plot through the use of this device. The close-up enables the viewer to see what is important in the shot and demands that you determine this in advance of shooting, with implications for the way your story is conveyed. As an example, in filming a dialogue between two actors, some people would be inclined to show more of the human reaction to a set of events, training the camera on the faces and hands of the actors to show the emotion behind the story. Others may prefer to focus on the mechanics of the action, with more emphasis on how the actual events are occurring and perhaps delivering a simpler reading of the action.

Controlling information

Visual and stylistic aspects of filmmaking are described in Chapter 6:1 and help in describing the means with which we convey the story. This project, however, focuses entirely on the ability to control this drip-feed of information making up the narrative to the audience and, when used alongside the previous projects, may help you deliver not only the plot, but also much more.

Stage 1

In preparing the plot for this film, it would be more effective to find something simple, a familiar plot that an audience can relate to. But if you want to try more advanced versions of this project, make the narrative more complex. Use simple linear stories, taking the audience from event A to event B, such as a delivery, a heist-and-getaway or a confrontation between two people.

Stage 2

Developing this film is going to be slightly different from other projects. When you have completed the visualizations stage and are ready to move on to the storyboard, work instead on much larger frames. Draw a frame the size of CD box or larger.

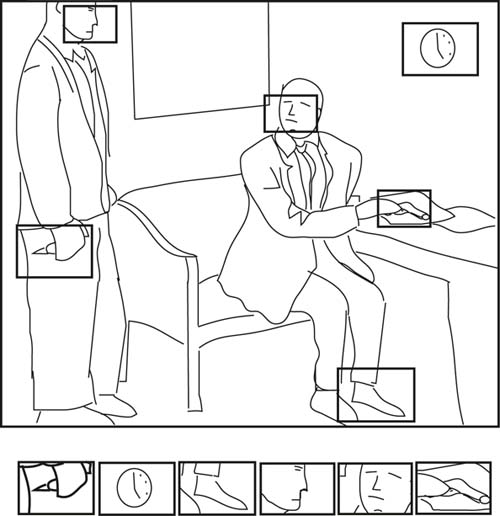

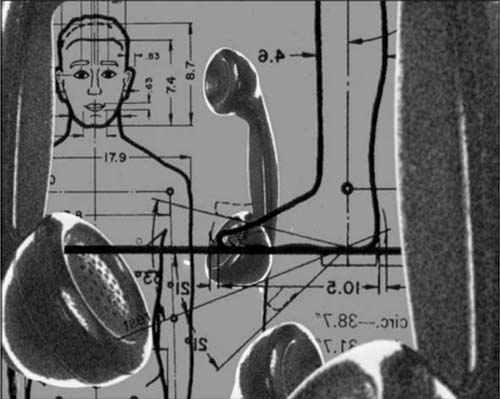

When you have completed a first draft of the storyboard you will then need to start drawing smaller frames around certain parts of the image, trying to home in on the essential parts of that shot. To do this, you could try making a number of window frames out of paper, at anything from one-quarter to one-sixteenth of the frame size. The aim is to see if you can isolate images within the frame which convey the primary information in that scene. Look at what is the most important section of that frame, what is the next most important, and so on.

Multiple shots in one frame

As can be seen in Figure 6.8, the single frame here contains several frames that are telling different parts of the story. The primary source of information is probably the gun on the table and the hand resting on it. But a close second are the two frames showing the faces of the actors. After this, you could look at the foot tapping nervously under the table and the clock ticking on the wall. All these sections of the frame give portions of the overall information contained within and it is for the director to prioritize each part when deciding how to point the camera. Does the hand on the gun need to be centrally placed in the frame? There are infinite ways to order the shot depending on what you want to show the audience and how much you want to ‘spoonfeed’ them the plot. Bringing unlikely elements to the fore now and then can add layers of meaning to a scene. Hitchcock demonstrates this many times as he draws our attention to a minor part of scene, often showing human quirks and frailties in the process.

Stage 3

When you have completed this exercise with all the frames in the original storyboard you are ready to begin sorting the new images taken from the larger frames into some kind of order. We need to build a new storyboard out of these images, paying careful attention to the order in which the close-up shots appear and the frequency with which they recur. It is likely that you will need to have more shots of shorter duration than in a similar film made without this device.

Stage 4: Shooting

Shooting this film is going to take slightly longer than other narrative films. Although you will be setting up more shots than in other films, you can make your task much simpler by asking your actors to play a scene several times while you take various shots from different angles. If you have access to additional cameras this would save time and make continuity problems less evident by shooting different parts of the scene simultaneously.

In obtaining the close-up, it is better to move the camera closer to the action rather than rely on the zoom control. Zoom tends to increase camera wobble and removes the opportunity, to a certain extent, for you to track or pan the camera.

Shooting tips for this project

Focusing

Like just about every aspect of filmmaking, even something as technical as focusing can be a creative tool. When working in close-up, the aspect of focus is even more emphasized due to the laws of optics. You can choose which part of the screen the audience look at when you decide which area will be in sharp focus; the focus tool is like an arrow pointing to the crucial part of that shot. But there is no reason why you should not challenge this convention by settling attention elsewhere in the scene. The director Kieslowski has some memorable images in his films obtained through a creative use of focusing.

Film View

Near the start of Three Colours: Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski, 1993), we see a doctor enter a ward containing the victim of a car crash. From the point of view of the victim we see a close-up, focusing on a few feathers on her pillow moving with her breath, while the doctor is a blurred figure in the background. This tells us that the victim is alive but also conveys something of the sense of bewilderment felt by her. The next shot is equally impressive: the camera fills the screen with her right eye and we see the pupil contract as a reflection of the doctor appears in the iris.

You may also find that some camcorders are designed to focus the object in the centre of the frame and reject your attempts at creative focusing, particularly if you want something on the side of the frame in focus and the main object in the centre not. If you do have a manual focus option, see the instructions in Chapter 2:3 for getting round this problem.

Camera wobble

When shooting close-ups you will find that the camera is going to reveal more shakes and wobbles than in other shots. Although a tripod is advisable for many shots, it would be useful to devise a more flexible solution that did not restrict the range of angles available to you, such as using a beanbag or similar movable, soft support.

Lighting

When you are working close to the action, lighting becomes an important factor. There are some lighting conditions that will aid you in trying to convey information and some that may confuse the scene. Avoid flat, dispersed light from fluorescent lights and household bulbs. Use light that is sharper and more directed at the action, so that the shapes of the subject are revealed and contrasting shadows are thrown. This will help to reduce the amount of extraneous information we see and draw attention quickly to what is important in the shot.

Extra shots

Finally, when you are shooting, it would be useful to get additional shots you had not previously planned for. When you feel you have shot all the parts of a scene you needed, look around the scene for anything else that could be used to break up the rigidity of the final edit. If we are constantly given crucial information the film becomes hard work, but if you can occasionally cut away to something not so crucial it may make for a more rounded, less frenetic film.

Stage 5: Editing

There are a number of points to consider when editing this sort of film with its dominance of close shots. As well as having a greater number of shots than other films, these may be shorter and you may find that it is useful to use cutaways - cutting to and from a shot repeatedly. For example, if we consider Figure 6.8, you may cut from the hand on the gun, to the face of actor 1, to the face of actor 2, and back to the gun. You will need to avoid bewildering the audience, however, and include regular longer cuts: too many short, sharp edits can be physically hard to cope with. To vary your shots when filming, you could try tracking and panning to link two close-ups together.

Evaluation

Much of the evaluation for this project can be seen as assessing how you told the story and what you emphasized. This project reveals your individual preference in how a story can be told, as well as encouraging you to focus on the essentials of a scene, simply by asking you to draw our attention to what you feel is the most important part of it. This sort of self-knowledge is worth a lot in helping you towards a personal approach to the medium.

- When you were shooting, were the shots you filmed close to the storyboard you prepared? You don’t lose points for deviating. It is more useful to assess which is the better document: the tape or the storyboard. For many filmmakers it is the former, since the camera shows you what you can achieve while the paper version only shows what might be achieved.

- How did your use of light alter? Did you become more aware of where you were placing lighting to reveal certain parts of a scene? Did the use of strong, directed light help you in simplifying the frame and making better compositions?

- Focusing will also have been a useful tool for composition - did it prove useful in close-up?

- When you were editing the movie, how did you feel the flow of the story was interrupted by the need to cut between the elements of the scene? You may have found it useful to use one particular shot as the dominant one and insert others now and then. The length of each shot itself tells the audience something about your priorities for the story and determines how they will read it, according to which shots are dominant. You may have decided to dwell on a particular, seemingly less significant, part of a scene in order to challenge the presumed priorities for that scene, changing the way we expect a scene to be shown.

I want something more challenging

To push this project further, try turning your attention to non-narrative ideas rather than action-orientated ones. You may find that you are then having to focus more on symbols and other signifiers of meaning rather than just signifiers of action. Expect to have to work hard on suggesting significance in each shot because the action in the frame won’t do it for you.

2. Continuity

Continuity in narrative filmmaking refers to the way shots go together to create a seamless chain of events. It is going to be the invisible tool that helps you bind your film together and link it as a single, whole experience. It is going to hide the nuts and bolts of filmmaking, creating an illusion of reality and merging separate pieces of film - sometimes recorded days apart - into one stretch of fictional time.

The need for continuity arises because the audience does not see everything. Time is compressed and space is shown only selectively, cropping the imaginary world we see. To illustrate this effect, try a test where you look only through a small tube. You start to feel the need for more information to tell you about your environment. If someone leaves your small frame of view, you want to know whether they have left the room. It is unsettling if there is a gap in your internal map of the room you are in. Watching a film is very much like this test, so one of your tasks is to provide the viewer with a complete sense of where we are, who is there and when any part of this changes.

Good continuity keeps the audience with you. The audience’s dependence on you for information is made more acute when you factor in the editing process. Now shots are broken up into small pieces and it becomes essential that some way is devised of maintaining the smooth flow of events on film.

Continuity is disrupted easily: the slightest object out of place, a confusing camera angle or a shift in the style in the film can all break the audience’s involvement with the illusion. The effect of broken continuity is unusually shocking; it momentarily drops the viewer from the fairground ride experience of watching the film and sends them back to earth with a knock. Of course, with such a noticeable effect, discontinuity is just one more trick for the filmmaker to utilize. If you are aware of the positive and negative effects of keeping continuity and disrupting it, you can choose when and how you employ these tools. To use the fairground ride analogy again, you can choose when to keep the ride smooth and when to give an unexpected jolt to the passengers, without risking the whole ride falling apart. In other words, maintain continuity closely and you then have the option of editing against it for sudden effects.

Narrative continuity

In narrative film, continuity is crucial. Various elements have the potential to cause problems during shooting and editing, including:

- technical factors such as changes in picture quality

- plot factors such as omitting crucial explanatory scenes

- prop and set factors such as clocks out of sync

- style factors such as a shift in the look of the film

- unexplained implausible moments such as exaggerated compression of time.

Know the rules, know how to break them

It is worth noting that bad continuity is not necessarily good discontinuity. In other words, simply ignoring the rules of continuity will not automatically lead to a ground-breaking film that has its own innovative look. Every film needs to have an internal logic where any disruption of the basic ideas of continuity is planned and incorporated into the film as a whole, so that it corresponds to its own rules. This may sound vague because each film has its own individual needs but, in general, rules are broken in a planned way rather than arbitrarily.

Go to: Chapter 4:5 to see how to plan effectively for an alternative approach.

Figure 6.9 In any location shoot, continuity of action is crucial, especially when dealing with several characters, as in this still from David Casals’s On Off.

Avoiding bad continuity

How do you set about ensuring that continuity is under control? The range of issues outlined below need to be considered.

Tape quality

This is less of an issue for digital tape but is important nonetheless. Use the same quality of tape throughout production, new ones if possible. Digital tape degrades far less than analogue tapes through reuse because it is built very differently, but there are other ways in which tape can be affected through length of use, so it is safer to buy new tapes and use a consistent number of times, usually less than 10.

Camera features

Make sure you remain with the same camera settings throughout production. If you start the film using, for example, an aspect ratio of 16:9 (sometimes called‘cinema’ on the camera), stay with it throughout unless you have a scripted reason to change. Set the white balance to the same values each time you shoot. White balance is often automatic on many models but check before every shoot; any unknown changes in lighting and you could end up with one shot having a warm, orange cast to it and the next having a cold, blue cast to it. Altering the white balance on purpose can be a valid tool, of course, allowing you to change the look of a scene.

Plot disruption

Even the minor absence of some small part of a plot can be baffling for an audience. For example, a shot showing a character in one location, a beach perhaps, followed by a cut immediately to the same character in an entirely different location, perhaps back home, needs some explaining. We have soon assumed that the character jumped in a car and drove home between the two shots, but we need to be shown it or told it with a subtitle, even if it is just a glimpse of the car speeding on the road for a couple of seconds or a title saying ‘later’. A narrative is like a ladder; its upward, linear progress depends on having all the rungs in place. Miss out a few rungs and the ladder still works but requires considerable effort to climb, and eventually you lose faith in the overall structure.

Closure: the viewer fills in the gaps

However, before we start handing the audience everything on a plate, there is a concept called ‘visual closure’ that refers to the ability of the mind to fill gaps in a narrative to make it into a coherent whole. If you draw a circle but leave out a few degrees of it or draw one with dotted lines, you will still recognize it as this shape, but the crucial point is that enough information has been given for us to conclude that it is a circle. Just a few lines in the right place and we can fill in the rest, just as in the example above we needed to see only a fraction of the car journey to see that it had taken place. Leave out the scene that connects the two locations and you risk losing the shape of the film as a whole.

Sound

One of the more subtle but still noticeable continuity problems is often in the soundtrack. Ambient sound, or sounds that are recorded in the background to each scene, will differ greatly, even those recorded on the same day in the same place. The reasons for this are looked at more fully in Chapter 5:3, but bear in mind that ambient sound has the capacity to make or break continuity. The use of devices to smooth over the changes in presence are one of the hallmarks of professional filming.

Go to: Chapter 5:3 to find out more about sound recording and Chapter 7:4 for ideas about editing with sound.

Style disruption

Style is something that occurs naturally as a result of the numerous decisions you make about camera angle, composition, music, editing and so on. Once you have noted the constant elements in the film, such as the kind of shots you use, dominant colours or style of acting, you need to nail these down and stick to them. There will be times in the film when you want to disrupt this conformity of style - for instance, in dream or fantasy sequences and flashbacks or to denote a radical change in the film’s pace. At these points you will certainly devise a very different look to the film, but it is a constant style throughout the rest of the film that allows you to lift other sections out of it so neatly. Try to establish the look of the film early on in the planning stage. Use a timeline to indicate the dominant style and where it is to be broken.

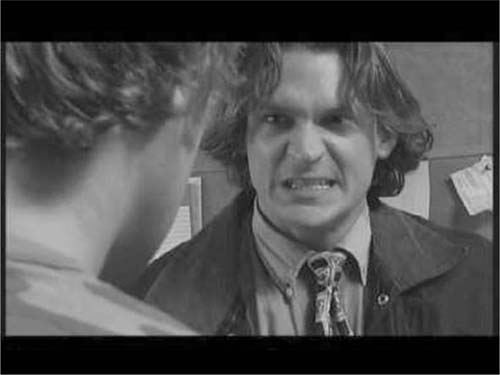

Figure 6.10 Over-the-shoulder shots like this help preserve a sense of continuity in dialogue scenes. Still from Crazy by Noel Stephens.

The action line

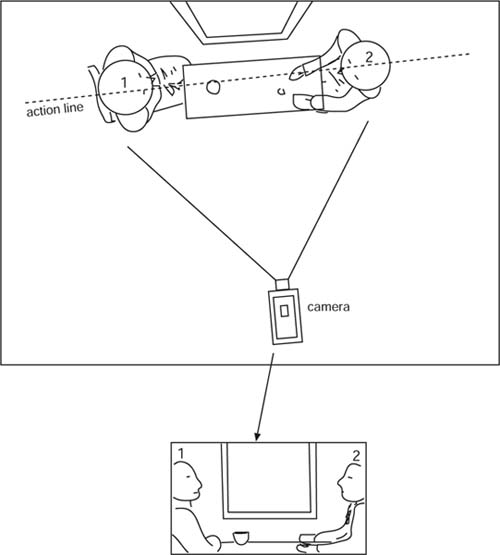

Among the devices we have looked at to ensure smooth continuity, one of the most useful regards the placing of the camera. This rule is also known as the 180-degree rule and has evolved to ensure that the fictional space created by a scene is sustained throughout. Both shooting and editing play a role in this. Every new shot has the potential to suggest that we are in a new location or at a new point in time. The purpose of the 180-degree rule is to reassure the audience that we are in the same place and that the events are happening in the same short space of time.

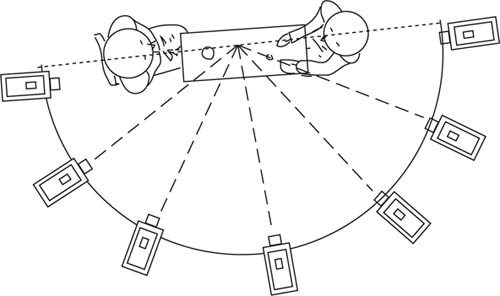

How the action line works

It works by drawing an imaginary line between characters in a scene and drawing a semi-circle that runs 180 degrees around them, on one side only. The camera must shoot from one side of the line, from any position. If we look at Figure 6.11, we can see what the camera records if it stays on one side of the line. In this shot the two actors are on opposite sides of the frame, actor 1 on the left, actor 2 on the right. The audience notes the position of the two actors and sets up a kind of internal map of the room accordingly. But if the camera goes onto the other side of the line, near the window, the actors seem to have changed sides, with 1 on the right and 2 on the left. The audience then ask questions: Did an actor move? Or did an edit go missing?

Figure 6.11 The action line.

The action line and the jump cut

A further use of the line is in avoiding the ‘jump cut’. A jump cut is an abrupt cut between two clips when the camera of each gives a slightly different angle or view of the subject. When framing a figure we will notice a disruption of our view by moving the camera slightly to the side and cutting between the two shots. It is as if you had filmed a tracking shot and left out a small piece of tape as the camera moves, as you may expect to see in badly preserved old silent movies. The effect does not destroy the scene but does introduce some hiccup in the flow of the film. As with all discontinuity, this is also a useful tool as it produces dissonance against the harmony of the overall continuity and, as anyone working with music will tell you, dissonance is a valued element in music composition.

The 30-degree rule

To avoid this effect, however, cameras are placed at certain locations around the action. Imagine a semicircle radiating around the main action, as if the camera is in the auditorium of a theatre looking at a stage. Cameras can be placed at least 30 degrees apart from each other around this semi-circle, but no closer. If cameras are closer than this and the two resulting close shots are edited together, the effect will disrupt the space of that scene. Cuts to new angles have to be sufficiently different to justify their occurrence.

Motion within the screen

The rectangle within which we see the film, whether it is a television or projection screen, is also a tool in achieving continuity in that we construct a map of the invented world of the film. Movement within and off screen needs to be handled particularly carefully. Explaining this gets a little complicated, but here goes.

There is a difference between scenes that are stationary and scenes involving forward movement, such as a chase or journey. Let’s take the first kind to begin with. Say you have a scene involving, for instance, some people within a room or in a particular defined space. If a figure walks off the screen we adjust our internal map of the scene and place a mental marker regarding where they are now. If they go left, we expect them to return from the left; if they exit right, that’s where they should re-enter. Ignoring this makes for an unholy mess in continuity. At worst, your audience are going to lose faith in the whole movie and start watching for more such continuity errors. Even a simple plot is then in peril, as now nothing the filmmaker is offering to the audience can be relied upon.

The other kind, and you were warned it gets confusing here, involves the reverse of this. Suppose you have a scene in which one character is chasing another. Maybe a policeman is pursuing a villain, or a Tyrannosaurus rex is chasing a jeep. In these kinds of scenes the participant will exit right (usually) and re-enter left, showing us that the journey or chase is constantly in the same direction, left to right, left to right. If you follow the piece on the action line earlier, then much of this problem is solved.

There is a convention regarding the direction actors will be moving when filmed. If a figure is going forwards or onwards metaphorically, in the script, perhaps to a new location or new part of the plot, we expect the figure to travel consistently from left to right across the screen, and the reverse when seen to be returning from somewhere. There are times when you need to imply onward or returning motion and this device becomes even more useful when you have few location landmarks to help orientate the audience. In David Lean’s Lawrence of Arabia, the exhausted Lawrence is journeying across a barren desert, and we see him go from left to right. When he later learns that one of his party has fallen from his camel many miles back, he returns for him and we see him go from right to left across the screen. With no landscape elements to help us to judge which direction he is going in, this becomes essential.

Film View

An interesting example of how movement from left to right is used can be seen in David Lynch’s The Straight Story (1999), in which an ageing and car-less man travels hundreds of miles on his only mode of transport, a lawnmower, to visit his long-lost and ailing brother. In many shots, Lynch places him travelling from right to left, thereby hinting that the man is returning home, travelling back to the place he needs to be.

Light quality and intensity

Since light is one of your tools for showing the passage of time, you need to ensure that light is constant throughout a scene if the audience are to view the events of that scene as contemporaneous. This means light should reflect only those changes to the scene that the audience can perceive — for instance, the approach of dawn, a car headlamp moving past and so on. Lighting used in a scene should be maintained at predetermined levels; if you are unhappy with the lighting of your scene, do not change it halfway through, redo the whole scene. If filming takes place over days or weeks, make careful notes of the position and intensity of lights. Similarly, daylight is notoriously unpredictable; a temporary cloud can radically alter the colour and lighting of a scene. The weather may influence the day you shoot a lengthy scene. Hollywood grew up where it did because it enjoyed near-perfect clear, blue skies almost every day. Continuity becomes easy, even if two parts of the same scene are shot days apart.

Continuity in non-narrative movies

Non-narrative movies demand a very different approach to narrative. They require that you embed continuity as a part of the whole structure of the film, not as an afterthought during filming. Nonnarrative movies such as music videos, abstract movies and multimedia projections used in live concerts are particularly susceptible to looking fragmented. At their most out of control, they look like you are channel surfing, looking at a number of clips of movies by different people. Of the following ideas, the more effective ones are those that are part of the planning and shooting stages rather than those placed over the film in post-production.

Methods of ensuring continuity in non-narrative

Single filter effect (edit software filters, not camera filters)

If your editing software has special effects that you can use to alter the look of clips — for instance, to make them change colour, stretch or change contrast and tone - you could apply one of these to the whole film, or at regular points. Restrict yourself to one filter only.

Tracking

A tracking shot — where the camera moves while it shoots, tracking the action - can make a good way of connecting shots. Decide on a constant speed of tracking and stick with it throughout the film. To enhance the effect, keep to one direction in the screen - for example, left to right. For example, you could show a slow, left-to-right movement of the camera along a beach, cutting then to a similar constant shot along a busy street.

360-degree movement

This device is particularly effective in linking shots. Decide on the height of the camera and the speed of the camera as it moves, then shoot everything while moving 360 degrees around the subject, at every location, throughout the film.

Common space

This involves including an object or space in the background that is present in each shot, and could be as simple as a fireside with picture frame. This is commonly used in scenes with dialogue where it is useful to be able to locate two actors within the same space by showing some common space or object in each actor’s frame. In a non-narrative film you could choose a single prop that is present throughout.

Transitions

At the editing stage, you will need to decide how you cut between scenes. The most common - the straight cut and the cross dissolve - could be developed by trying something a little more noticeable. An example could be to fade fast to white as the picture cuts, suggesting flash photography.

The length of the shot

A style of editing that uses short cuts, with a high turnover of clips, will encourage the viewer to see these clips as linked in some way, even if the subject matter is not. Therefore, we tend to see a montage sequence consisting of a lot of quick images because the diversity of images needs to be balanced by speed of perception. But what is a ‘long cut’ or a ‘short cut’? In this case you could think of a quick cut as half a second or less and a slow cut as anything from three to five seconds, but your subject matter will dictate how fast your cuts will be.

Motif

In non-narrative films, a motif can be used with some thought to what kinds of objects or colours add to the overall theme of the movie. For example, in an interpretation of the word ‘anger’, we could justifiably use the colour red as a motif in the film. To stand as a motif you would have to see the object or colour recur often enough to be noticed. Alternatively, you could use images of a clenched fist or a brick hurtling towards a window, letting us see more and more of it as the film proceeds.

Linked imagery

For this idea we could take a look at Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). After a lengthy start where we see ancient pre-human apes, Kubrick needed a way of jumping tens of thousands of years into the future without disrupting the flow of the movie. If ever there was a time to use a continuity device, this was it. His response was to have the camera follow a bone thrown high into the air, and immediately cut to a similar-shaped, bone-like spacecraft, occupying the same space in the frame. This is a daring way of connecting two shots that could not be more dissimilar, visually. While shooting, you could look for parts of the scene that visually resemble a part of another, with the aim of linking the two later.

Sound

This is a last resort method of connecting shots and is not the most effective way. A single piece of music is dubbed over the whole film as with a music video. If you want to use sound in this way, try to use a particularly noticeable home-made soundtrack of sounds, rather than music, and one where you have altered the sounds or looped them, producing a repetitive, rhythmic effect.

The Crunch

- In narrative, continuity is crucial

- In non-narrative, broken continuity can be a useful tool

- Get to know the rules of keeping continuity and break them wisely

- Continuity is developed both in the script stage and also while shooting

- In non-narrative movies, beware that the movie doesn’t look fragmented - use continuity devices in editing or shooting

- Get to know the action line and the 30-degree rule

- Use good quality sound and take care of ambient sound.

Project 15. Urban legends

What this project is for: to create a narrative movie

Time: allow a week to plan, another to shoot and two weeks to edit

What this project is about

This project enables you to put into practice many of the ideas looked at in narrative storytelling. Continuity, camera work, lighting, sound, scriptwriting, genre editing, all contribute to this short film.

The inspiration for it rests on the many urban legends or myths that are present in every community. These tales may or may not be true, but are certainly spooky and tend to be atmospheric, tense, with occasional spots of action and delivering certain veiled messages - in other words, perfect for narrative films. They also tend to play on the audience’s fears, phobias and nightmares, engaging spurious moral codes - for instance, in Final Destination (James Wong, 2000), Scream (Wes Craven, 1996), A Nightmare on Elm Street (Wes Craven, 1984), Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978) and My Little Eye (Marc Evans, 2002). More original movies rely on mythical events where fantasy and reality can be merged to dramatic effect.

Stage 1

See Chapters 4:4 and 4:5 to help work on a story. For ideas, look in local newspapers, paranormal journals such as Fortean Times and weblinks to urban legend sites. Look for:

- A strange event that took place near where you live

- A supernatural tale

- A myth from indigenous peoples (Native American, aboriginal, for instance) that could be updated - see Whale Rider (Niki Caro, 2002) for a good example

- A cautionary tale (most horror films today tend to have such moral overtones).

Weblink

http://www.forteantimes.com/ Journal of the weird and unlikely.

Stage 2

See Chapter 4:7 for help with developing a visual style to the movie. Look at #c5-1">Chapters 5:1 and 5:4 on location shooting, Chapter 5:2 on lighting and Chapter 5:3 on sound recording to help with technical aspects. When shooting, make sure you stick to what is available — use friends as actors, props you already own and your own house as location. Close-ups are going to help in this movie more than any other kind of shot; they obscure imperfections in your non-professional actors’ performances and also heighten tension and drama.

Stage 3

Make sureyou stay within genre editing as outlined in Chapter 8:1, but feel free to experiment with a looser narrative style similar to the kind seen in music promos with simple stories. After the first cut, leave the film for a week or more and then come back to it with a more objective eye; you will then be able to do a re-edit where you try to reduce the length of shots. One of the most common faults of short films is shots that have not been cut enough. Try shaving off a few frames and watching the results, although make sure you keep a master copy of the first version safe to return to if necessary.

Evaluation

It is important with this movie to let it have an outside life beyond your friends and crew. Take it to local screenings and get comments from other filmmakers. If you get good responses, send it further afield to festivals or cable TV slots.

Go to: Chapters 9:10 and 9:11 to get more details on getting your work seen.

I want something more challenging

Option 1

To stretch your skills further, try writing a script that adds layers of meaning to the film. Look at Chapter 3:2, ‘How films work’, to get ideas about this. Stretch the cultural and social connotations more by offering connections to bigger world events. Urban myths by their nature tend to be localized, but some have engaged wider fears about the world, such as the fear of Native American ghosts in Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982), which perhaps reflected a wider awareness of historical and current political issues about Native Americans.

Option 2

Alternatively, try making a silent movie - one where there are sounds but no spoken dialogue. It will push your skills of storytelling to the limit, resting all information on what the camera can show rather than the cheap shortcut that is dialogue. It is also a great way to learn about sound environments (see Chapter 5:3 for details on sound environments).

3. Documentary

The current period of documentary is arguably approaching a kind of golden age. Factual films have earned huge receipts in the global box-office in films such as Fahrenheit 9/11 (Michael Moore, 2004), Touching the Void (Kevin MacDonald, 2003), Super Size Me (Morgan Spurlock, 2004), Capturing the Friedmans (Andrew Jarecki, 2003) and The Fog of War (Errol Morris, 2003). The industry and critics have responded in the awards ceremonies, most controversially by awarding Moore the Cannes Palme D’Or in 2004 for his searing look at post-9/11 America. But it wasn’t just his partisan view that caused a big stir - it was the point at which it broke through the $100 million barrier in box-office receipts, a return not seen before in documentary films. Suddenly, fact could be as enticing as fiction.

At some point it became acceptable for a documentary to be entertainment, but it is the filmgoers who have driven this change rather than the distributors, who failed to see that audiences were receptive to films that looked at social or political issues. Andy Glynne, director of the London Documentary Group, acknowledges the change:

‘Touching the Void is a great documentary, has done incredibly well in the cinema and has helped to change what people think of as a documentary. This idea that it had to be really didactic and straightforward has gone. Now you see dramatic reconstructions, animation, drama documentary, music video sequences, and you see it getting into feature films like American Splendour, which uses fake documentary-style footage and archive footage as part of the film.’

Documentary on a low budget

The low-budget sector is seen to be dominated by the short film, the calling card of the future feature director. But equally vibrant in this level is the documentary filmmaker. To a certain extent, this kind of filmmaker is more self-sufficient than others due to the size of the crew needed - the one-person self-shooter and editor is common. They also have few opportunities for funding, with many television companies cutting factual budgets before more popular dramas. The political nature of some documentaries - but by no means the majority - is also an obstacle. For award-winning documentary maker Phil Grabsky this is a problem, but not one without a solution.

‘Generally speaking, there has been a general lack of nerve of TV people as well as a slavish rush to secure the highest possible audience, even if that means the lowest possible standards. But things are starting to change - and largely because digital technology has allowed filmmakers, including myself, to say “Hey, we can make the films we want with much less reliance on TV.” At the same time, audiences are seemingly less happy with TV and are now going to cinemas to watch docs.’

Often, filmmakers seek other routes for finance so as to continue making the films they want to make without interference from outside agencies. Britain’s Spanner Films, for example, runs a successful training company to help other filmmakers, and sells DVDs direct to the market. Its 2003 movie Drowned Out told the story of Indian villagers refusing to leave their land to make way for a hydroelectric dam. A version was sold to an American cable TV company, which helped fund more work. A later movie, Baked Alaska, focusing on oil drilling in the northern state and global warming, raised finance by asking for small donations from viewers of their previous films.

Figure 6.13 Director Franny Armstrong of Spanner Films shoots her film, Drowned Out, portraying the fight by Indian villagers against the destruction of their homes by a reservoir.

The severe financial and physical obstructions (the extensive travelling and research) would suggest that this field of the low-budget sector should be diminishing. But the very particular survival skills of its exponents have created an industry shaped by realism and able to overcome these obstacles.

Interview

‘I attended NYFA and mostly went on sets and observed the director at work, visualizing myself as the external director working on the same film because my ambition was to be in his position. I have worked in different positions on small productions that have not made it on TV - basically showreels. I read a lot of practical filmmaking books till I felt that it was possible to make my own documentary and believe me it is possible.’

Amaru Amasi, documentary filmmaker, USA

Background to the revival

Documentary started its revival in the mid-1980s. Errol Morris’s The Thin Blue Line (1988) made a great impact by incorporating dramatic devices usually seen in fiction movies. Its production values were high, it had a classy soundtrack by Philip Glass and it used narrative reconstructions to illustrate what had happened. The film told the story of the wrongful conviction of a man currently serving a sentence. The film attracted attention by meticulously laying out the evidence against the conviction, leading to a successful appeal after the film was released. Morris himself preferred the term ‘non-fiction’ to describe his film, reflecting his sense that it signalled a departure from previous documentary films. It also allowed him to enter the film for festivals where the documentary tag would have barred his entry.

The term ‘non-fiction film’ itself was first coined by a group of influential documentary filmmakers of the 1960s, Drew Associates. Within this group, working primarily for television, were the brothers Albert and David Maysles and Don Pennebaker, who made the Bob Dylan portrait Don’t Look Back (1967). Prior to this group we could go back further to a group of French filmmakers in the early 1960s who for the first time admitted that the presence of the camera made a difference to what was being filmed. This ‘cinéma-vérité’, as it was known, changed the way documentary was perceived and led towards the form becoming more subjective and perhaps more honest about its capabilities in that it could not claim to be entirely impartial and dispassionate.

Broomfield and Moore

A further step was taken with the work of British filmmaker Nick Broomfield and American writer/filmmaker Michael Moore. They have placed themselves firmly within their films, showing how the presence of the filmmaker affects the subject of the documentary and positively trading on this fact. Antecedents in this can be seen in the books of Hunter S. Thompson, such as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, which sparked a whole new kind of news reportage called gonzo stories, where the writer was firmly a part of the subject.

In Moore’s Roger and Me (1989), the director tries in vain for three years to track down General Motors’ chairman Roger Smith in order to confront him with the human consequences of GM corporate policy of redundancy in Moore’s home state. Moore jumbles chronology and places his own feelings about the subject at the heart of the film - both these ideas would have once been outside the parameters of documentary. Moore’s motivation was the sense that facts don’t adequately portray the situation, that they need illuminating somehow by meeting human response. In successive films since then he has sought to display the human consequence of his subject matter in what may seem to some like headline-grabbing stunts or to others like original ways to pierce a cloak of secrecy.

In Bowling for Columbine, Moore took a teenage victim of the high school massacre referred to in the title to the headquarters of the store where the bullets that were still lodged in his body were bought. The store then promised to remove the sale of these bullets from local stores. In this sequence we could see the transformation of the documentary from detached observer to slightly subjective view and finally to subject of itself. It was less a description of the situation than an attempt to intervene and make a new situation. Less successfully, Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11 asked senators to sign up their grown children for Iraq tours of duty in the armed forces. Documentary filmmakers remain divided about Moore’s tactics, with many suggesting that his films remake the documentary form too radically.

Nick Broomfield deserves a place in this chart of the changes within documentary as a filmmaker who has sought out subjects which say something about wider society and avoided explicit political aims. As a result, films such as Biggie and Tupac and Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer, with their subtle exposition, result in highly charged political statements, without having to resort to rhetoric.

Documentary convergence

Although much used in media circles, the term ‘convergence’ has something to tell us in describing the emergence of documentary in its newest incarnation. It has begun to sprout offshoots that are clearly documentary but incorporate other elements we normally expect to see in narrative film, including montage editing, the reconstructing of events to show what happened rather than simply tell it, the use of unusual and challenging structure, and imaginative use of the camera.

Go to: Chapter 10:2 for more ideas on what convergence means to the film industry.

Music video-style sequences are now common devices for breaking up less easily digested facts into more audience-friendly chunks. Animation has also crept in, allowing the filmmaker to use satire and metaphor to illustrate points, as in Super Size Me, which uses brief animations extensively throughout. An extended sequence in Bowling for Columbine made by South Park creator Matt Stone (a former resident of Columbine) combines a set of ideas that would have tested the attention span of most filmgoers if presented in any other form. By using cartoon characters and an offbeat narration the sequence can raise complex questions, in this case the relationship between American history, a state of social fear and gun culture.

These animated or music video sequences allow the filmmaker to state clearly that this is a very separate part of the film, thereby allowing a new set of rules to come into play. In much the same way, a narrative film uses montage to denote that certain sequences are to be seen as separate to the rest of the film, perhaps as flashbacks or intimations of the inner state of characters.

A further significant movement has seen the documentary form spill out into narrative, creating a hybrid movie. Jonathan Caouette’s accomplished Tarnation (2003) uses archival footage to tell his own turbulent story, a strange combination of documentary and drama in an entirely new variation.

Film View

Made for $218 and edited with Apple’s iMovie software, Caouette’s movie Tarnation moved documentary and drama beyond the constraints of either form, and was a correspondingly big hit at the Cannes Film Festival in 2004. Caouette started making films at the age of 11, borrowing a neighbour’s camera to document his turbulent childhood. After 20 years of hoarding tapes and photographs, he embarked on a rough cut of the footage as a side project. After a festival director saw the movie, the tape was passed to director Gus Van Sant, who signed on as producer, calling it ‘a brilliant and devastating biographical documentary’. The official website is http://www.i-saw-tarnation.com/

Figure 6.14 Jonathan Caouette’s debut feature Tarnation (2003).

Other films have also obscured the division between forms in this way, such as American Splendour, highlighted at the start of this chapter, while other films appropriate documentary devices for narrative ends, exploiting the unpredictability and rawness of the form, as in The Blair Witch Project or My Little Eye (Marc Evans, 2003).

‘My advice for first-time documentary makers? I now have what I term the Nike mentality — just do it. Look out on the streets, question yourself about things you don’t understand and find out the answers on camera from different societies.You don’t need to go to film school or have a rich uncle, just have film passion. Research your subject, sometimes you don’t need to because it unfolds before your lens into a story. Pick up a camera like the Sony or the Canon and start shooting. If you are not ready yet, read books on filmmaking or magazines like this one that’s the only way you can get advice on what to shoot with.’

Amaru Amasi, documentary filmmaker, USA

Figure 6.15 In the forests of South America, documentary filmmaker David Flemholc worked in particularly adverse conditions for his film House of the Tiger King (2004).

Where next?

To some extent, the non-fiction film is becoming more challenging and provocative than the narrative film, stealing from other forms but doing so with the aim of a truer representation of the events it is portraying. The difference is that we now question what the meaning of truth is, and how to locate it. Filmmakers agree that once you point a camera at a subject, it stops functioning as itself and becomes a part of film rather than a part of real life, something that anthropologists and sociologists realized years ago. If the camera makes the objective subjective, then the filmmaker is only following the logic of this by presenting a film that uses elements from fictional and factual forms.

The result is a form that is more attractive to the aspiring filmmaker. The low costs and opportunity to be as creative as with narrative film means that this form is a valid place for a filmmaker to work; it can teach a great deal about all forms of filmmaking.

The Crunch

- Documentary film has evolved into other forms

- This is a great place for the filmmaker to build knowledge about filming — try it out

- Non-fiction film often requires you to use narrative filmmaking methods, so it’s going to help your narrative movies too

- Always tell the truth (at least your own interpretation of it, anyway)

- Get to know how to convey ideas and opinions through images, through the way you use the camera

- Use non-fiction as a low-budget method of making movies (no actors, no sets).

Tip For further viewing, try the following, though they are not easy to find in video stores: Medium Cool (Emile de Antonio, 1969), about the 1968 Democratic Convention; Hearts and Minds (Peter Davis, 1975), about the US involvement in Vietnam; Italianamerican (Martin Scorsese, 1970), a portrait of the director’s parents;Day of the Fight (Stanley Kubrick, 1953), a portrait of preparations for a boxing match.

Project 16. My obituary

What this project is for: to investigate documentary filmmaking

Time: allow a few days to plan, a week to gather all the footage and another week to edit

What this project is about