Identifying Work-related Problems

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Name and describe the two stages of problem identification.

• Distinguish between problems and distractions.

• Use the problem-solving tree to track the steps you need to solve your own work-related problem.

• List the four key work situations covered in this course and the typical work-related problems associated with each, and identify which of the four are relevant to you in your current job.

• Use the Do You Really Have a Problem? checklist to determine whether you have a work-related problem.

PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION IS A REAL SKILL

One of the things that business leaders value most about problem solvers is their ability to identify problems. It sounds basic, but it isn’t. You can’t start solving a problem until you have identified it.

Consider Metropolitan Toys. The company had a serious problem with its new, high-profile product, but no one knew it until Andrea Jefferson started some detective work after hearing from some dissatisfied customers. You can be sure that Andrea was not the first person to hear those complaints. But she was the first person to listen, to identify the complaints as a problem.

Metropolitan Toys asked a work group to investigate the causes and solutions to the problem uncovered by Andrea. They learned that customers had made oral and written complaints to several departments, including sales, public relations, and billing. Unfortunately, no one in those departments had looked beyond the individual complaints to see a pattern. If Andrea hadn’t taken action when she did, Metropolitan’s new money-maker might have missed the holiday season completely.

There are two stages to problem identification. The first is when the alarm goes off—you sense that something is wrong. The second is assessing the problem to determine what steps to take. The next two sections of this chapter explain what to do at each of these stages.

THE ALARM GOES OFF

You’ll never get a chance to solve problems if you can’t “hear” the alarm go off. It is essential to be able to sense that something is wrong.

Make Sure You’re Listening for the Alarm

There are many reasons that some people never hear the alarm. Here are several.

The first reason some people don’t hear the alarm is that they just want to get their work done. In fact, they want to get it done with the minimum output of thought and energy. A problem could jump up and hit them in the face, but they won’t feel it if it means they have to do things a little differently or work a little harder.

Think About It …

Think About It …

Have you ever worked with anyone who just wanted to get the job done, regardless of the quality of the product or the safety of the process? How did you feel about his or her approach? Who were the losers?

Make sure that your own desire to get the job done isn’t drowning out the sound of the alarm that means something’s not right. Most of the time, it is easy to fix. The quality of your work will improve as will your pride in it. This course will show you how, even when the solution is more complicated.

A second reason some people don’t hear the alarm is their fear of the all-too-human tendency to “kill the messenger.” We’ve all had enough experience with the phenomenon to know it exists. Sometimes people get angry with the person who tells them bad news, rather than putting their energy into solving the problem or finding out who was responsible for the problem.

Andrea Jefferson, for example, almost gave up her investigation at Metropolitan Toys when she learned that the real problem involved Metropolitan’s new moneymaker, the Super Karate Frogs video game. Tension around the new product was high, and she was afraid of becoming the scapegoat, that is, being blamed for the problem. That was one reason why she immediately brought her boss into the picture and made sure she had his support.

Think About It …

Think About It …

Have you ever uncovered a problem at work, only to keep the news to yourself because you were afraid that your organization might try to involve you in the blame? What thoughts went through your head? What did you do eventually?

Make sure that you haven’t shut down your alarm system because you are afraid of the consequences of reporting a problem. For one thing, you may be missing mistakes of your own. Correcting your own error is a much better route to job security than not saying anything about it. In addition, the big problems requiring reports to senior management are few and far between. In between may be many small problems that you are able to resolve collegially.

Finally, there are the people who hear the alarm but just don’t think it’s ringing for them. This is the it’s-not-my-problem syndrome.

Think About It …

Think About It …

Think back to times when you’ve had a problem as a customer. Maybe the important birthday present you ordered through a catalog never arrived. When you called a customer service representative at the catalog company, you were told that your order had been shipped weeks ago, thank you and goodbye. This kind of response clearly implies that it wasn’t the company’s responsibility that your order didn’t arrive, it was your fault for not receiving it. How did you feel? Did you deal with that company again?

To avoid the it’s-not-my-problem trap, remember that your customers’ problems are your problems. All of us have customers at work, people to whom we supply goods and services both inside and outside the organization. When something goes wrong for a customer, make sure that you hear the alarm ringing for yourself as well.

A Problem Interrupts the Flow of Your Work

Once you are listening for the alarm that tells you something is wrong, the next step is to figure out what it is. What do problems look like? How do you know a problem when you meet one?

A simple generalization is this: A problem is something that interferes with the routine flow of your work. In fact, the interruption is usually the alarm that tells you something is wrong.

Here are some examples of interruptions that are also alarms.

1. Jen is finishing a layout in a graphic arts unit when she notices that some of the materials she is using are seriously substandard.

2. Ron manages a bakery in a large shopping complex. One morning while he was setting up, he discovers that the ovens are not heating properly.

3. Kim installs computer equipment. On the way to her 2 PM assignment, she notices that the customer’s address she was given is for a building with a “gone out of business” sign on it.

4. While Carol is working on invoices, a customer calls to complain that the last three deliveries from Carol’s company have been late.

5. Bob is doing end-of-year inventory at a discount sports supplies store where he is a manager when he notices an entry for some expensive foreign skis. Bob is upset because he is sure that his store does not carry that brand of skis.

Problem Versus Distraction

Of course, there are many interruptions during the day. Not all of them will require problem solving.

Which of the following interruptions are problems?

• Kay spills a cup of coffee on her desk, soaking all of the papers on which she was working.

• It’s the company’s annual holiday party. No one is allowed to miss the boss’s annual holiday speech, so Kevin has to stop working.

• Bonnie’s dentist calls to postpone the appointment she had scheduled for next week.

• The daily ledger Sam was working on doesn’t balance.

• The machine Sarah was operating grinds to a halt, and there is a red light blinking.

• A summer storm knocks out electrical power for the area, and Jim’s computer goes down.

If you had a hard time answering this question, don’t worry. Many people use the word problem to refer to any event that is troubling or out of the ordinary. In this sense, spilled coffee is a problem, and cleaning up the coffee is a solution. As we discussed in Chapter 1, use the term problem in this course to refer to troubling interruptions for which the solution is not immediately evident.

Problem solving is not recommended for spilled coffee and other interrupting events. These are distractions, and they generally take care of themselves. In the preceding example, three of the interruptions were clearly distractions: Kay’s spilled coffee, the company’s annual party, and Bonnie’s call from the dentist.

The ability to distinguish between distractions and problems is an extremely important work skill. Employees who go into problem-solving mode when a distraction occurs will soon get a reputation for overreacting and poor judgment. Imagine how you would react if you knew that Kay had responded to the coffee spill by composing the following memo for her boss: Four Proposed Alternatives for Removing the Coffee Spill from My Desk.

It is true that there is no hard-and-fast rule to distinguish problems from distractions. Take the example of the electrical storm. The power outage proved to be an annoying but routine disruption at Jim’s company, which had established good, clear procedures for dealing with the effects of power outages on their automated system. At another company down the road, however, there were no procedures, and the power outage created a major problem.

If you are not sure about the difference between distractions and problems, keep reading. You will find that most distractions either take care of themselves (the holiday party comes to an end) or require you to take a simple step (clean up the coffee).

There is one exception to this general rule: The difference between a distraction and a problem is, to a certain extent, in the eye of the beholder. Your distraction may well be my problem. For example, the person at the desk next to me plays the radio so loudly that I cannot concentrate, but it doesn’t seem to bother anyone else in the office. In such cases, it is the responsibility of the person with the problem to convince the others that there really is a problem; otherwise, he’s likely to have trouble getting anyone to listen.1

KNOWING WHAT TO DO NEXT

Something has interrupted your work, and you have satisfied yourself that it is not a mere distraction. It looks like a problem, but what should you do next? Should you tell your best friend at work? Should you send an immediate memo to the CEO of the organization? Taking an incorrect step can be as defeating as not doing anything.

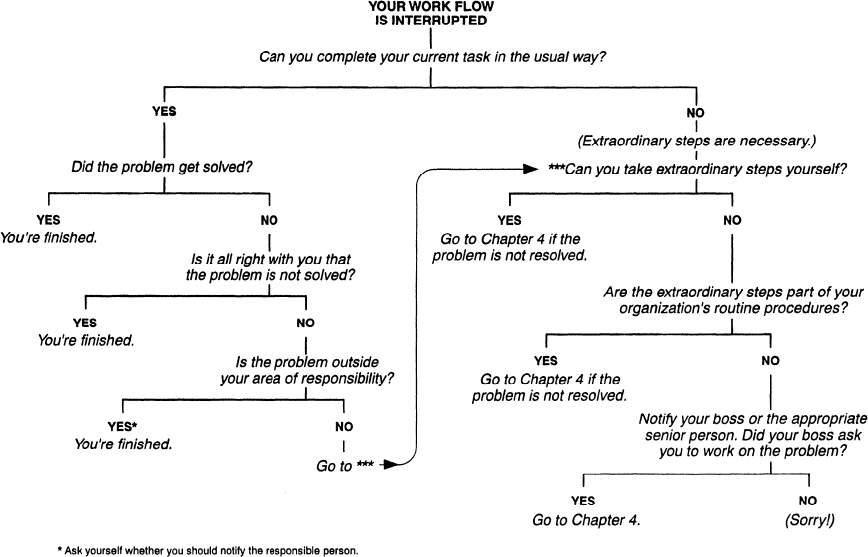

Knowing how to proceed is a valued skill. In this section, you will learn a simple procedure to follow anytime you encounter a problem and are not sure what to do next. It consists of a series of questions that can only be answered yes or no (see Exhibit 3–1). While you are learning, be sure to follow the procedure exactly. Soon it will be second nature.

As you can see, the problem-solving tree looks like an upside down tree with branches. The first branch occurs as soon as a problem interrupts your work. Ask yourself if you can complete the task you have started in the usual way. Do not skip this step, because important and very different consequences flow from the yes and the no answers.

Let’s start with an example of a no answer. Consider Ron, the manager of the bakery. When he asked himself whether he could continue with his task (morning set-up at the bakery) in the usual way, the answer was no. The bakery could not run if the ovens were not in working order.

Ron had to stop his set-up routine and deal with the problem of the ovens. He had to do things that were not in his usual routine. We will call these extraordinary steps. In the tree in Exhibit 3–1, all the branches on the negative side concern situations in which extraordinary steps must be taken to complete the task that was interrupted.

Common sense will tell you that this is not the only possibility that will arise in problem situations. Take Jen, the graphic artist. The problem that had interrupted her—the poor quality of some new supplies—did not prevent her from completing the layout assignment that was her immediate task because she had kept some high-quality materials from previous projects in her desk. So she answered yes to this question: Can you complete your current task in the usual way? She did not have to take any extraordinary steps to complete the layout assignment.

You probably felt instinctively that the main difference between Ron (and the no branch of the tree) and Jen (and the yes branch of the tree) is attention to the problem. In the no branch, work cannot proceed until the problem is addressed. In the yes branch, work can proceed.

In the yes situations, there is danger that the problem will not be addressed. By the time Jen completes the layout assignment, she might forget about the substandard supplies. The next time she starts a layout assignment, she would find herself in a predicament, having nothing but substandard supplies.

The Yes Branch: Make Sure You Are Not Evading a Problem

Jen’s situation illustrates the importance of checking through the problem-solving tree every time a problem arises. That’s because problems can often be evaded. Remember, Jen found some old supplies in her desk and was able to keep on working. The task gets completed, but the problem is not solved. The possibility that there’s a problem is easily forgotten.

In Jen’s case, she did check through the problem-solving tree. The next question she encountered was: Did the problem get solved? Her answer was no. As you can tell from the problem-solving tree, a no answer meant that she was not yet finished with the problem-solving tree.

(A scenario with a yes answer is as follows: Just as Jen was completing her layout, Kasey walked in with a large box of supplies and announced that it was a replacement from their supplier for a defective lot that had been delivered last week.)

When Jen answered no, she asked herself the next question: Is it all right with you that the problem is not solved? Jen quickly answered no, because good-quality materials are essential for layout quality acceptable to her boss and her company.

Then Jen asked herself if the problem was outside her area of responsibility. Sometimes we stumble across problems in the workplace that are clearly outside the areas for which we are responsible.

Think About It …

Think About It …

Have you ever been in the middle of a work assignment and discovered a problem in the operation of another company unit? Assuming you wanted to see the problem fixed, what did you do?

In a situation such as that suggested in the preceding Think About It … section, there are at least two ways you might go about resolving the problem. You might find out who the responsible person in the company is and ask whether that person is higher in the hierarchy than you or your peer. In the former case, protocol probably will require you to involve your boss. In the latter case, you may be able to communicate directly with the responsible person.

Alternatively, you might ask yourself whether the problem requires a formal or an informal approach. Informal approaches are likely to be appropriate in situations in which the responsible person should have the opportunity to fix the problem quietly (especially if this is the first occurrence of the problem). Here’s an example. It’s payday and you find all your unit’s paychecks on your desk, right out in the open where anyone could see them. You know that’s a serious breach of company security and privacy guidelines. You’re ready to call the accounting office and complain when the culprit walks in. There’s a new clerk, and it’s his first day on the job. He looks anxious. Instead of making a complaint, you take the time to explain company policy to him.

Formal approaches are more appropriate when the identification of the problem should be recorded for some reason. For example, you know this is a recurring problem for the company, and nobody seems to be fixing it. In the case of the paychecks as an example, it’s now the fifth week in a row that the paychecks have been dumped on your desk. The personnel office has told you that they are not satisfied with the new clerk, but he happens to be a customer’s nephew so they need to document their steps carefully. You call personnel and formally notify them that there’s a problem with paycheck distribution.

In Jen’s case, the answer again was no; this problem was not outside her area of responsibility. As you can tell from Exhibit 3–1, the negative answer meant that Jen was not finished with the problem-solving tree yet. She had to move to the top of the no branch.

The No Branch: Situations in which You Cannot Complete Your Task

The no branch covers all the situations in which extraordinary steps have to be taken in order to address the problem. As you can see from the problem-solving tree, ask yourself if you can take the extraordinary steps yourself or if you need higher authorization. Jen’s extraordinary step was simple: Tell the unit’s procurement clerk what had happened so that new supplies could be ordered. Jen was certainly authorized to take that step, and she did. Her problem was solved.

The no branch brings us back to Ron, the manager of the bakery. His ovens needed fixing so that the bakery could start baking. Company policy stated that only skilled mechanics were authorized to work on ovens. Ron could not take the extraordinary steps himself, so he moved down one more step on the problem-solving tree. He asked himself whether the extraordinary steps were part of his organization’s routine procedure. As it happened, the answer was yes. The company’s management handbook instructed bakery managers to call in an authorized repair person, and to notify the regional office in writing. That’s what Ron did, and his problem was solved.

It’s not always that easy. Consider Andrea Jefferson. Her problem had definitely not been solved. Let’s review what she did according to the problem-solving tree. Her work was interrupted by some calls from customers upset by late deliveries. This interruption did not prevent her from proceeding with the routines of her job, supervisor of distribution at Metropolitan Toys. When she asked herself the next questions on the problem-solving tree (Did the problem get solved? Is it all right with you that the problem is not solved?), the answers were emphatic no’s. Nor was it the case that the problem was outside Andrea’s responsibility.

Once Andrea had conducted some research, she discovered that the problem seemed to concern the company’s new product, Super Karate Frogs, and another company unit, the new products division. Andrea did not have the authority to take the next steps herself, nor did the company have routine procedures covering this situation. So Andrea notified her boss, describing to him the problem she had uncovered and the steps she had taken. Andrea’s boss was impressed with the work she had done and asked her to lead a work group he convened to address the problem. As you can tell from the problem-solving tree, Andrea had finished with the tree questions. It was time for her to read Chapter 4.

IDENTIFYING TYPICAL PROBLEMS IN THE WORKPLACE

Before moving on to Chapter 4 with Andrea, spend some time on sharpening your problem-identification skills. This section describes four key work situations: processing, interacting with customers, special assignments, and supervising. The problems frequently encountered in these situations are described for each. Identify which of the four key situations are relevant to your current job (and the people who work for you). It’s possible you’ll find that all of them apply to you, because many jobs combine elements of all four. Then study the typical problems associated with each relevant situation. Knowing which kinds of problems you are likely to encounter will sharpen your ability to recognize them in the future. (Remember that you will learn ways to deal with problems like these in subsequent chapters.)

Processing

Transaction processing can be done on paper or electronically. Examples are invoices, payments, claims, orders, and requests concerning accounts. Processing of things includes operating a machine, assembling, disassembling and repairing items, performing laboratory tests, and construction. Routine services that do not involve interaction with customers, such as janitorial services and landscaping maintenance, are also included.

Problem Analysis

Here are some typical features of problems that occur during processing.

• Problems typically interrupt the flow of work in such a way that some extraordinary step must be taken to resume work or complete the task.

• Routine procedures have been developed to cover frequently occurring problems. These procedures are likely to be in the quality-control mode, especially at manufacturing sites.

• Problems have an immediate adverse effect on the quality of end-services and -products. (A customer may be billed for the wrong amount, or a defective part may be manufactured.)

Example

A senior account clerk who processes written applications for new accounts is inputting information into a computer file. She encounters (a) an erroneous zip code that the computer refuses to accept and (b) date-of-birth information that the computer will accept but that conflicts with information elsewhere on the application.

Interacting with Customers

Interacting with customers may include providing service to customers, in person, over the telephone, or in writing. Typical situations include providing health care services, serving meals, telemarketing, and interviewing.

Problem Analysis

Here are some typical features of problems that occur during direct service.

• The interruption pulls the worker away from the current task. Consequently, the interruption often appears to be the problem. There is a tendency to solve the problem by ignoring the customer in order to return to the original task.

• Many situations arise for which no routine procedures have been prescribed. When there are procedures, they are typically part of customer service.

• The problem often may have no immediate impact on the quality of end-services and -products, so there is less incentive for workers to address the problem.

Example

The senior account clerk who is processing written applications for new accounts is called by a customer who has questions about the monthly charges on her bill. The clerk is not a customer service representative, but takes the call anyway. While examining the customer’s record, he notices that some new account information had been incorrectly transferred to the permanent account. He observed something similar last month and assumed the problem was the result of human error; but now he wonders what happened.

The example of the senior account clerk is typical of many jobs. The senior clerk often performs processing and direct service, and the types of problems he encounters are different in each area of work.

Special Assignments

Special assignments may include staging a special event, conducting a search through files, or representing the boss/work unit at a special event.

Problem Analysis

Here are some typical features of problems that occur during special assignments.

• There are unlikely to be routine procedures for problems.

• It is likely that the problems are systemic.

• It is likely that the problems identified are the consequence of someone else’s actions (someone other than the one on special assignment, often decreasing that person’s sense of responsibility for the problem).

• It is likely that the problem is complex and requires sophisticated problem-solving skills.

Example

The senior account clerk is asked by his boss to attend a meeting introducing the new financial management software package just purchased by his company. During the presentation, he starts to suspect that the new software will not cover a key transaction in the new accounts area. He’s not sure what to do.

Supervising

This situation covers supervising or managing a unit or units in a company or other form of organization.

Problem Analysis

Here are some typical features of problems that typically interrupt supervisors and managers.

• Many of the problems arise from the actions of subordinates (either problems they have created or have identified).

• The problems may form patterns pointing to systemic problems in their own unit.

• The problems may compete for the supervisor’s attention with regular supervisory tasks, tempting the supervisor to let the problems slide.

Example

The supervisor of the new accounts unit is informed by a clerk that the company’s new financial management software package will not cover a key transaction in the new accounts area. Several small crises interrupt the supervisor before she can think about the software issue. She’s angry because she knew that the software design people weren’t paying enough attention to her unit. She’s also worried because the possible omission could create serious problems for her unit. She starts to wonder how she could test the actual software when three more crises erupt on the floor.

YOU HAVE A PROBLEM

Recognizing problems at work is the first step toward solving them. Be alert for clues that something isn’t working right.

One of the reasons people take this course is that they and their bosses have identified a work-related problem and they want to find a solution. In other cases, people who are taking this course realize while they are reading that there is a problem in their workplace that they want to tackle. Working on a real-life problem on the job is a great way to learn and put your learning to good use at the same time. If you have identified a work-related problem that you want to solve, use the Do You Really Have a Problem? checklist in Exhibit 3–2. If all of your answers are yes, you are ready to proceed to Chapter 4.

Do You Really Have a Problem?

1. Your work flow has been interrupted by complaints, discrepancies, or some other indicator that there is something wrong. Yes ___ No ___

2. You have established that there is a pattern. (It’s not just an isolated incident.) Yes ___ No ___

3. You’ve been spending work time on it. Yes ___ No ___

4. It adversely affects your performance at work. Yes ___ No ___

5. It’s fixable. Yes ___ No ___

6. There’s something you can do about it. Yes ___ No ___

7. Your boss has assigned you to work on it. Yes ___ No ___

The first step in problem solving is learning how to identify problems. There are two stages: First, you sense that something is wrong; second, you assess whether it is a problem or a mere distraction.

Once you have satisfied yourself that you have a problem, then you should use the problem-solving tree to decide what your next step is. The first question the problem-solving tree asks you is: Can you complete your current task in the usual way? If you answer yes, you follow the series of questions on the yes branch of the tree. If you answer no, you follow the no branch.

It is important to sharpen your problem-identification skills through studying the four key work situations identified in the last section of this chapter. They are processing, interacting with customers, special assignments, and supervising.

1. Which of the following is not a true statement about problem identification?

(a) There are two stages to problem identification: sensing that something is wrong and then evaluating the problem.

(b) You’ll never get a chance to solve problems if you can’t hear the alarm go off.

(c) Some people fail at problem solving because they have a hearing impairment that prevents them from hearing the problem alarm go off.

(d) Some people fail at problem solving because, even though they hear the alarm go off, they believe that the problem belongs to someone else and not themselves.

1. (c)

2. Which of the following statements about problem identification is (are) true?

(a) Some people fail to identify problems because they just want to get the job done, and dealing with problems would take extra time.

(b) Fortunately, 90 percent of the problems in the workplace are easy to identify, and no training is required.

(c) Some people fail to identify problems because they fear the human tendency to kill the messenger.

(d) Statements (a) and (c) are true.

2. (d)

3. A good indication that there might be a workplace problem is when:

(a) an alarm goes off, and you sense something is wrong.

(b) something out-of-the-ordinary happens at work.

(c) you suddenly realize your salary is not as high as it should be.

(d) either (a) or (b) occurs.

3. (d)

4. Which of the following is not a valid statement about workplace problems and distractions?

(a) Problem solving is recommended for both workplace problems and distractions.

(b) Your work can be disrupted by both problems and distractions.

(c) Problems are troubling interruptions for which the solution is not immediately evident.

(d) Distractions generally take care of themselves.

4. (a)

5. There is a rule you can apply to distinguish between distractions and problems that is always valid.

( ) True

( ) False

5. False

6. Once you have identified a problem, what should you do next?

(a) Use the problem-solving tree to determine what to do next.

(b) Put the problem in writing, and forward it to your manager.

(c) Submit a request for an interview with a senior manager in your organization.

(d) Talk it over with your friends in an informal setting, such as lunch.

6. (a)

7. What is the first question you should ask yourself once you have identified a problem?

(a) “Can I resolve this problem by myself, without involving anyone else?”

(b) “Can I complete the task I have started in the usual way?”

(c) “Is this really a serious problem for the organization?”

(d) “Is there a reward in this for me if I continue?”

7. (b)

8. What is the main difference between the yes and the no branches of the problem-solving tree?

(a) In the yes branch, unlike the no branch, work can proceed without solving the problem (with the danger that the problem will never be addressed).

(b) In the yes branch, you can solve the problem by yourself; but in the no branch, you need to involve other people.

(c) In the yes branch, this really is a serious problem for the organization; in the no branch, it is not.

(d) There is a reward for you in the yes branch; there is no reward in the no branch.

8. (a)

9. Which of the following is an appropriate consideration when you want to inform another unit in the organization that you have identified a problem in the unit’s operations?

(a) Whether the people in that unit have been nice to you in the past

(b) Whether a formal or informal approach is better

(c) Whether the responsible person is above you in the hierarchy

(d) Both (b) and (c)

9. (d)

10. Which of the following is not one of the four key work situations?

(a) Processing transactions or things

(b) Interacting with customers

(c) Special assignments

(d) Socializing with co-workers

10. (d)

_________________

1 You can still use this book, even if you are the only one who believes that there is a problem. Be sure that convincing others that there is a problem is part of the definition of the problem (see Chapter 4).