CHAPTER 7

Pricing Continuous Improvement and Analytics

A wide variety of forms of analysis inform the gamut of pricing decisions. Some forms of analysis will be done infrequently, in response to a unique challenge or opportunity. Other forms of analysis will be done on a more regular basis. While the methods for conducting pricing analytics can be found in pricing textbooks such as Pricing Strategy (Smith 2012), a framework for managing pricing decisions needs to clarify when and where these analytics should be routinely applied.

There are three areas of pricing analysis that are ripe for turning into routines: (1) pricing across the offering innovation cycle, (2) price variance policy improvement process, and (3) in-market price improvement process. These three pricing routines are used to guide an offering from conception throughout its life cycle. They provide a decision feedback loop to enable pricing to be improved over time. These are areas where the organization’s skills can be improved through repetition and continuous improvement. And, these are areas that most leading firms address once a year or more frequently.

It must be accepted that prices will often need adjustment once the offer hits the market, and that price variance policy, too, gets adjusted between the initial launch period and the time the offering hits maturity. Pricing analytics is used to measure the relationship between market pricing and market acceptance, between price variance policy and policy effectiveness, and between price execution and all prior pricing decisions. These measures are used to adjust decisions and improve pricing performance.

Continuous Improvement Process

As one leading pricing practitioner stated, “Pricing isn’t an event, it’s a process.” In this statement, this leading pricing practitioner was partially referring to the fact that pricing analysis and decisions aren’t a once-done always-done activity. Instead, prices are constantly evolving, shifting to the input of new information or changes in the marketing environment.

The Continuous Improvement Process is a useful paradigm for structuring the relationship between pricing decisions and pricing analytics (Deming 1986). It provides a managerial feedback loop, connecting decisions with outcomes and allowing room for course corrections. In designing a process for directing pricing analytics, the Continuous Improvement Process provides a solid template.

Many decades ago, W. Edwards Deming addressed the managerial challenge of enabling firms to find a means of improving managerial decision-making. One of the key challenges for many managerial decisions is that once a decision is made, action takes place and then management moves on to the next challenge. The insight Deming had was that, for management to improve its decision-making capability with respect to an ongoing process, it has to be informed of the outcomes of its decisions and be able to course-correct to reach its destination goal.

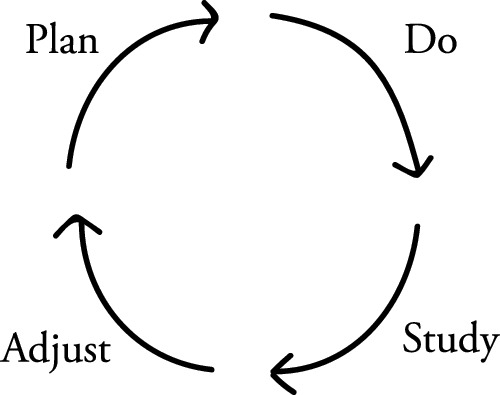

The resulting Continuous Improvement Process championed by Deming has been updated and adapted many times. Total Quality Management (TQM); Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve and Control (DMAIC); Six Sigma; and Kaizen are all process improvement processes that have a conceptual origin, or at least a kinship, to the Continuous Improvement Process (see Figure 7.1).

Figure 7.1 Continuous Improvement Process

In a simple description of the concept, the Continuous Improvement Process has four key parts: Plan, Do, Study, and Adjust (PDSA). (I have chosen to refer to A as Adjust though the original paradigm and most others have used Act. This is just a personal preference made to highlight the decision-oriented nature of that part.) In Plan, management sets out an agenda for action that can be measured. In Do, management and the team take action to execute against the plan. In Study, the results of that execution are measured against the plan. Study is key for driving improvement, for outcomes that cannot be measured cannot be managed. Potential causes—both exogenous and endogenous—for deviations away from the expected outcomes as defined in the plan are identified and investigated. In Adjust, the information and understanding gained in the last cycle of the process are incorporated into decision-making for the next cycle. Adjust is an opportunity to decide to repeat, improve, or restrategize completely, which may mean abandonment.

Pricing decisions rely upon making predictions, such as “that customer will buy at X but not Y,” or “the demand at Price L is K percent higher than the demand at H.” But these predictions are notoriously imperfect.

All the desired data for informing a pricing decision won’t exist. Even when data does exist, its accuracy may be imperfect, providing a rough estimate of the appropriate price or price variance rather than the exact, precise, perfect number. And, even when inaccuracy can be managed, the relevancy of the data may be called into question if for no other reason than its basis is usually in the past and pricing is about predicting behavior in the future. More to the point, some of the data necessary for guiding pricing can only be gathered by making a pricing decision coupled with a hypothesis of the outcomes of that decision, then executing and measuring the outcome. That is, the needed information for guiding pricing often develops over time through a hypothesis-driven experiment followed by course corrections.

Hence, that leading pricing practitioner is correct: Pricing isn’t an event. It’s a process.

This isn’t to say that pricing analysis cannot help. It is fair to acknowledge that pricing analysis won’t always perfectly provide the right pricing answer. Rather than spend all the firm’s time and treasure on making a perfect pricing decision, executives must make these decisions in the face of uncertainty but with the knowledge that the best information that could be used was used, and the best decision that could be made was made.

What the Continuous Improvement Process allows for is for these decisions to be reviewed and adjusted as new information or market changes are identified.

Using the Continuous Improvement Process for managing pricing decisions encourages executives to review their decisions in light of new facts that were gathered or created since the last decision cycle, and then make improvements. It creates a process orientation that enables prices to be tested against the market and adjusted in light of new information or market changes. It provides a path for rapid improvement in pricing.

Importantly, with respect to pricing, the Continuous Improvement Process provides an approach to conducting business experiments. In effect, it turns all pricing decisions into experiments in which the outcome of a decision is tracked and used to inform future decisions. Pricing experiments are highly useful for detecting a means to manage pricing better from the execution level even up to the corporate strategy level.

As a bias, the Continuous Improvement Process encourages executives to make the best decisions possible in the time frame allowed with the expectation of improving that decision in the future. It accepts that even the best-made plans often go awry, but executives can never give up. Instead, they must choose a path, play the course, and adjust to reach their goal.

Offering Innovation and Pricing Decisions

Even at the early inception of a new offering, pricing should be engaged. Though the offering innovation process is generally the province of engineers and scientists engaged with marketers and business developers, leading firms also engage pricing professionals in the innovation process. With respect to the Continuous Improvement Process, pricing during the offering innovation process is the formulation of the initial pricing plan.

Value engineering, a corollary to value-based pricing, demands that products and services are designed, developed, and delivered in accordance to the requirement to meet customer needs profitably. This implies that during the offering innovation process itself, the benefits that the offering is to provide must be defined, the value customers would place on those benefits needs to be understood, and the price and volumes must generate revenues in excess of the cost to develop and produce.

Shrinking Life Cycles

The importance of getting the price and benefits relationship right continues to increase due to the shrinking of the overall competitive life cycle itself (D’Aveni 1994).

At one time, executives would create their corporate strategy under the assumption that once they developed a capability or offering that the market valued, they could profit from it for decades. Since they had decades to profit from the capability or offering, errors in pricing could be fixed over time and the firm would be able to recover from mistakes. Such a leisurely attitude is no longer affordable.

The duration of a firm’s ability to monopolize a market with a new capacity or offering has shrunk from decades to months, if not even shorter.

Consider that the Apple iPad was first released in 2010 to much fanfare. The world had never seen anything like it before and wasn’t even sure what it was. It could perform the role of an e-reader but cost much more than comparable products and seemed to be geared toward a much larger possibility. But it didn’t make phone calls and was too large for the pocket, anyway. It didn’t have a keyboard and wouldn’t replace a laptop. So what was it? The world didn’t really know, but the market gave it a try. Would it succeed? Would it face competition? To both of these, the answer was a historic yes.

Not only did Apple sell over 7 million units in the first six months, but Samsung reengineered its Galaxy to match the iPad and took significant market share in the new tablet market in early 2011. By 2012, Microsoft, too, had a significantly competitive entry in the market with Surface. Within four years, products, brands, and configurations of tablet computing solutions had proliferated beyond expectations and the market was reaching maturity.

In the Apple iPad story, we see that the duration of Apple’s ability to dominate the market alone wasn’t decades or years; it was months. Despite the large amount of product innovation in software, hardware, and design, a sizable portion of Apple’s competitive advantage in this market had been imitated and eroded in just months.

The Apple iPad story serves as a reminder to executives that the offering life cycle is short and getting shorter, and that the importance of coming to market with the right relationship between the offer’s benefits and price is getting greater. Executives must seek to reap profits during every phase of the offering life cycle—not just during maturity—therefore pricing is paramount in every phase of the offering innovation process as well.

Offering Innovation Process

We can map the integration of pricing decisions into the offering innovation process. As a template for crafting this map, we use the standard phase-gate innovation process. Many firms in the material sciences, natural resources, engineered products, and health care industries have offering innovation processes that span years. Other firms, such as those in the software, retail, entertainment, services, and consumer goods industries, have offering innovation processes that are much shorter. Their new product development processes will vary to suit their individual needs. Yet even for firms that do not use the phase-gate model, it can serve as a reference for guiding the alignment between innovation and pricing.

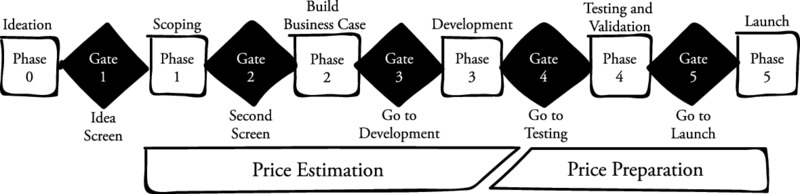

The standard phase-gate innovation process begins at a point of ideation or discovery (see Figure 7.2). Once the offering’s concept is developed, it is screened by management for market and firm appropriateness.

Figure 7.2 Phase-Gate Innovation Process and Pricing

If deemed appropriate, the offering enters the innovation process. At phase 1, the offering’s opportunity is scoped, meaning the market size and competition are evaluated to determine if the opportunity is worth pursuing. Recall, market sizing and competitive intelligence are key ingredients to pricing decisions, thus pricing can enter the innovation process at phase 1.

If screened for approval, the business case for competing in the identified market is developed in phase 2. The business case defines the offering to be developed. In defining the offering, executives are delineating the requirements for both the features and expected benefits to be delivered. It also includes the development plan, expected production or service delivery costs, and price capture. Thus, once again, pricing is part of the innovation process.

At phase 3, the offering is developed. In phase 4, it is tested and prepared for market. In phase 5, the offering is launched, the planning and preparation is complete, and the offering has entered the execution part of the Continuous Improvement Process.

In the phase-gate process of offering innovation, pricing issues arise at the very start of the process and continue indefinitely. Yet the pricing requirements during the early phases of the innovation process are not the same as those during the latter phases. In the early phases, the goal of pricing is to estimate the market potential and profit potential of the new offering. During the latter phases, the goal of pricing is to prepare an offering to go to market. Just as these pricing requirements change, so does the need and type of pricing analytics change over the innovation process.

Early Phase Price Estimation

In phases 0 through 2, the goal is to identify ideas with the potential to be profitable. This potential is defined through addressing five broad strategic marketing questions:

1.What is the whole offering? The whole product includes an understanding of how an offering will impact direct customers, the engagement of customers with others, and the overall value chain. It includes an understanding of how the offering affects up-front costs incurred by customers as well as total lifetime usage costs, which may include disposal.

2. What is the relevant competitive alternative? The relevant competition will include directly and indirectly competing offers. It may include substitute approaches customers are using to reach the same or similar goals in the absence of the innovation. And for many, it will definitely include the default choice of most customers: Do nothing.

3. What is the differential value of the innovation? This goes to the issue of understanding how the offering is better or worse than the competing alternatives. It also goes to the issue of understanding the benefits customers would be willing to pay for.

4. How does the differential value vary between market segments? Accepting that different customers have different needs, firms must engineer offerings with an understanding of how these needs differ. Some segments will pay dearly for a given set of benefits. Other segments will not. The market opportunity of a new offering will be strongly influenced by the size of these segments and the willingness of customers to pay.

5. What is the customer addressable horizon? The customer addressable horizon defines which segments will be targeted

to be engaged in the initial offering launch. It will include an understanding of how these customers are currently reaching their goals, whether they will come from a competitor’s market share or through increasing the market size by engaging a new market segment. It will also include a description of how this customer segment will be engaged and why the new offering would compel them to purchase.

Each of these questions is core to the understanding of the value of the offering to the target customers of the innovation. More specifically, they are model elements of the exchange value to customers of the innovation. This exchange value to customers can be used to estimate the price of the innovation once it hits the market.

The price estimate is necessary for executive decision-making in taking an innovation from phase 0 through 2. This price estimate should include a range defining the lower and upper bound of expectations. By developing the price estimate through a model of the exchange value to customers, executives can update the model and estimate as new knowledge becomes available or as market composition and demands change. While most models of the exchange value to customer can be created using simple spreadsheets, specialized software has been developed to aid in the development and maintenance of these models as key facts evolve. With this price estimate and the ability to update the price estimate, a business case for developing and launching the product can be made and evolved over the innovation process.

Informing the price estimation with facts will require market knowledge. At this phase in the innovation process, gaining breadth and depth of insight is generally more important than gaining perfectly accurate measurements of any one single fact. A proven best practice for gathering the needed breadth and depth knowledge is through secondary research into known facts about the market coupled with primary qualitative market research in the form of focus groups or executive interviews.

In focus groups or executive interview research efforts, discussion leaders and interviewers will listen directly to potential customers. They will probe for insights to understand customers’ needs, what drives those needs, and how important addressing their needs will be. These research techniques are not intended to provide a statistical measurement but rather to cover the breadth of issues related to an innovative offer. Primary qualitative research provides the context into which an offer will engage its markets and how the market would wish to be engaged. It clarifies the landscape into which an offering will enter. Qualitative research forms the basis for defining the questions a researcher may wish to ask in a later survey-based effort.

These qualitative research techniques, focus groups, and executive interviews have been found to be the most reliably useful approach to defining price structures that match customer willingness to pay. They may not define the exact price points to use, but they do reveal what creates or undermines value within the market, and therefore the best structure of prices to match the value customers derive from an offering and the expected range of prices to capture.

The choice of who within the potential market should be engaged in focus groups or executive interview research efforts is extremely important. Not everyone in the market will understand or care about the innovation, but some will. The sampling approach to focus groups or executive interviews should identify the few customers that can provide deep insight into their needs and how they would be willing to be engaged. The best researchers would prefer a small sample of highly informed and highly engaged customers within their focus group or pool of people to be interviewed to a large sample of uninformed individuals that give only cursory answers.

Later Phase Price Preparation

In phases 3 and 4, the firm must prepare to enter the market with a price on the offering. That means taking the information gathered during the business case development phase and firming up the price estimation in preparation for an actual launch. In almost every firm (most but not all), salespeople can’t sell and finance can’t bill for an offering that lacks a price.

The more focused set of questions that may be raised in preparation for launch can be reduced to three key informational needs:

1. Who actually will make the purchase decisions? In business markets, this would include executives who make economic trade-offs between offers and routes to improvement as well as a more broadly defined buying commitment that includes influencers, end users, champions, screeners, procurement agents, and gatekeepers. In consumer markets this might be the user or it might be a provider or gift giver. Depending on which role individuals take, their evaluation of the benefits and perception of the price of an offer will vary.

2. How sensitive are those customers to prices and points of differentiation? Though many businesspeople believe their market is extremely price sensitive, many experiments have shown that markets are less price sensitive than suspected. Instead, customers often become very sensitive to differences in benefits between offers and are willing to accept substantial differences in price to acquire the benefits desired. This question refines the rough segmentation effort done earlier with a more precise understanding of the segments to attack and the price variances that would be allowed to attract those segments, and which segments will be ignored or served only on an opportunistic basis.

3. Which competing offer would customers choose? Given a set of features and benefits with different brands and prices, customers will make trade-offs and select the offering that they believe will best meet their purchase goals. This question goes to the heart of the price and volume trade-offs.

At this point, the goal is to pinpoint the price and price variances that will be allowed in going to market. For some offerings, this might be sufficiently addressed through refining the model of the exchange value to customers with further qualitative market research. For other offerings, executives will rely on a survey-based market research approach to provide quantitative insights. In very specific industries and cases, executives may even conduct a price test.

While both qualitative and quantitative research techniques are useful in pricing, and both can be used to set prices, their applicability to a specific pricing challenge differs. Interview and focus groups are best at answering broader questions related to the price structure and overall flavor of price. In contrast, survey-based techniques are generally better for determining specific price points.

The most academically supported and industry accepted survey-based approach to measuring price sensitivity for new offerings is conjoint analysis. There are many forms of conjoint analysis including trade-off analysis, discrete choice, choice-based conjoint, adaptive choice-based conjoint, and menu-based conjoint. Each of these specific techniques, as well as a few others such as MaxDiff, seek to quantify the trade-offs customers will make between offerings and price. And each of these techniques is taught in advanced market research courses or can be accomplished using specialized software and services.

There are other forms of survey-based market research for pricing, but for leading pricing researchers, these alternatives have been superseded by conjoint analysis. Many of them suffer from measurement biases. Others suffer from providing no more insight than what could have been attained from a good model of the exchange value to customer or by simply looking at the competitor’s prices.

Recall that a key strategic issue in pricing is whether an offer will be priced to penetrate, skim, or be neutral in the market. Pricing research can clarify the relationship between price and benefits, and therefore inform executives of the relationship between their price choice and the resulting price positioning. The choice of the desired price position may result in a very different price than that revealed to be possible or perhaps even optimal in the pricing research, due to the business strategy of the firm aiming for a specific price positioning. Even in this case, the research is useful, for it demonstrates where a chosen price would position an offering once it enters the market and therefore enables management to reach its target price position with greater certainty.

By integrating pricing into the offering innovation process itself, executives are able to go to market with offers that more successfully reach their target and at a more accurate price. Not all new products will succeed, indeed over 90 percent of them fail. But at least executives can enter the market with their offering with a solid plan on how to price it and what kind of price variance would be acceptable.

Corning Inc., an engineered-glass firm, uses elements of this approach to its new offering innovation process. Corning’s phase-gate process shares many elements with the standard template provided earlier. Early in its phase-gate process, the company’s salespeople, marketing professionals, and engineers develop clarity regarding the benefits of a new offering, the market that would be attracted to that offering, and that market’s willingness to pay through the development of a model of the exchange value to customers. Later, in the phase-gate process, Corning’s model of the exchange value to customers is updated to include new information gathered through a more formal executive interview process. Similar approaches to pricing and new offering innovation have been observed in the medical products, medical instruments, pharmaceutical, and chemical industries. Any firm with lengthy delays between ideation and product will likely benefit by marrying its pricing with the offering innovation process.

Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement

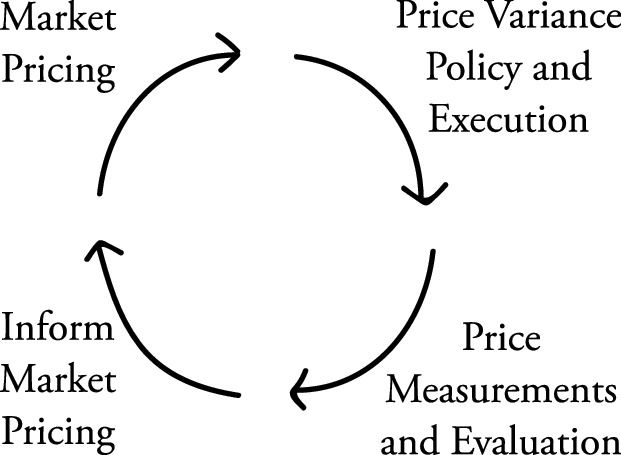

Even before an offering leaves the innovation process and the initial market-level pricing is set, people will ask about discounts and promotions. Price variance policy decisions arrive early and often. Firms can manage the decisions and improvements to these decisions using the Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement (see Figure 7.3).

Figure 7.3 Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement

Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement provides a feedback loop between price variance policy and price execution to optimize transactional pricing decisions. It continues to drive price variance policy decision improvement over the entire in-market life of an offering.

Following the Plan, Do, Study, Adjust elements of the Deming Continuous Improvement Process, Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement starts with setting a price variance policy. Once this policy is set, the firm executes within the plan. Following a period of execution, a transactional data analysis is conducted to understand the effect of the policy and clarify the room for improvement. Then executives meet once again, with the data in hand on the results of their plan and make a decision. Often, this decision takes the form of repeat, improve, or rethink (that is, reject).

The ongoing nature of Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement is important, for price variance allowances change over the lifetime an offering. Some firms will not allow new products to be discounted, others will allow for initial promotional efforts at launch to be greater than those expected once the offering has entered the market. Once in market, the types and sizes of price variances allowed may change over time.

At the Plan phase, we find price variance policies are often offering-specific. Some firms disallow price variances on high-end offers while allowing price variances on low-end offers. For instance, in the Porsche, Audi, Volkswagen, Skoda nameplate lineup of Volkswagen, discounts and promotions become more common as one moves toward the lower end of the lineup but rarely, if ever, are seen at the Porsche level. Abercrombie & Fitch undertook a similar approach in the brand lineup with its namesake outlets, which have fewer discounts than its secondary brand, Hollister. Other firms take the opposite approach in allowing deep price variances on high-end offers while holding prices on low-end offers constant. This latter approach is common in software and services markets where variable costs are low and fixed costs are high.

The timescale of a Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement cycle is generally on the order of a quarter. Dot-com firms with high-frequency transactions may reduce this down to the order of a day, where low-frequency transaction firms such as those engaged in specialized and expensive engineered solutions may allow for as much as a year between policy reviews. Accelerating the frequency of price variance policy reviews is important, for it enables management to take an experimental test-and-measure approach to improving decisions over the default approach of “this is the way we have always done it.”

For many, price variance policy is considered the province of sales and channel marketers, but they cannot act alone. As price variances have repeatedly shown their ability to destroy profits, finance often seeks to constrain their depth. And due to its possible impact on price positioning, marketing, too, should be engaged in these decisions. As with other pricing decisions, analysis from the pricing function routinely informs price variance policy decision-making.

Rules, processes, culture, and incentives are the typical areas reviewed in Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement. Rules refers to the choice of which offers are allowed for price variances and which are not, how deep those price variances can be, what type of price variance is allowed, and under what conditions is that price variance allowed. Process refers to the price variance approval process and decision escalation process, that is, who makes what decision when and who can override that decision. Incentives and culture refers to the monetary and nonmonetary methods for guiding price variance decisions in the field.

The purpose of price variances is to influence customer behavior. Obviously, one behavior under the influence of price variances is that of encouraging customers to purchase. Other behaviors can also be influenced such as encouraging customers to transact, receive, and pay in a specific manner or channel, or encouraging customers to purchase more frequently and be more loyal, or purchase less frequently but in larger quantities, or purchase with more regularity to allow for cost reductions in production.

Price execution—the Do phase—follows the guidance set by the price variance policy. This is the step in which salespeople sell against their plan and quotes, invoices, and accounts receivables are all managed. In addition to following the price variance policy, an important part of price execution is timing and resource requirements. Transaction pricing, which requires interdepartmental coordination, multiple approval levels, or other forms of delay and management attention can kill a firm’s ability to perform and increase the firm’s costs of sales. This operational procedure itself is often subject to a Continuous Improvement Process of its own.

Since price variances are granted only in order to drive specific customer behaviors, a key part of price variance management is determining if the price variance policy influenced customer behavior, and if so, did it do so in a manner which improves profits. Measurements and monitoring in the Study phase are required to evaluate whether that price variance policy was effective in its course. Feeding those measurements back to decision makers for their review completes the decision-outcome feedback loop.

Common measurements of transaction pricing analytics include average selling price, average discount depth, cumulative discount depth, discount by type, discount by depth, discount by market segment, and so on. They span into customer response metrics of elasticity, cross-product elasticity, and cross-channel elasticity studies. In business markets, they span into price waterfalls, price bands, and price-to-market segment studies. In consumer markets, issues of forward buying and stockpiling are also examined. They can include price impact studies, volume hurdle analysis, and achievement studies. They can even include price contagion studies to see if a negative price variance on one sale-impacted price captures on others. We have also seen firms conduct studies of customer lifetime value by discount method to determine if discounting is profit enhancing or simply increasing churn.

Since the information technology revolution, many advances in software have reduced the costs of monitoring and analyzing price variances. Firms can use off-the-shelf desktop software or specialized enterprise software to enable faster and more frequent reporting on price variance policy.

At the Adjust phase, specific price variance polices are selected for repetition, improvement, or retirement. If the policy achieved the desired change in customer behavior, its continuance may be warranted. If not, that policy may need to be ended or at least improved and made more targeted. Ending a price variance policy is never popular, but continuing a bad policy cannot be justified based on precedence alone. Decisions have objectives. If they fail to achieve their objective, new decisions should be made.

The review phase can allow for increases or decreases in price variances. If specific price variance policies are found to be extremely effective, management may wisely choose to expand those policies toward other market segments or channels. If they fail, management should choose to end them or at least tighten restraints on their application.

A major value of accelerating the review cycle of price variance policy is its ability to conduct market tests. Price variances can be turned into hypothesis tests. A price variance hypothesis may take the form of “if we allow for this kind of price variance, then we believe we will attract a specific market segment.” The execution of that price variance allows for the gathering of market responses to measure the ability of that price variance to drive the chosen and specific customer behavior. Reporting on the results enables the hypothesis to be confirmed as true or false. Thus, management can use these results to improve their thinking and develop more informed insights about the market, resulting in more targeted hypotheses and tests.

A business-to-business distributor found Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement to be highly valuable. Initially, the company had no systematized rules regarding price variances. It knew it was extending order size discounts to encourage larger orders, but didn’t know if that process was profit enhancing. Through a study of the company’s historic transactions, it found that these policies led to forward buying that depressed sales in future periods more than they saved on costs of sales fulfillment. Plus, they encouraged industry-wide price promotions, effectively tipping off an unintentional low-engagement promotional war. Importantly, they depressed the opportunity for cross-selling between products due to the infrequency of interacting with customers. As a result, management chose to improve this policy by adjusting order size discounts proportionate to shipping and handling cost savings. They also acknowledged that their key goal was repeat purchases. As such, they chose to test a rebate program to encourage larger wallet share and customer loyalty. As of the time of writing, the results of that test are not in. But it is clear that management found Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement enabled them to get a handle on their discounting and promotions.

Market Pricing Continuous Improvement

At some point, price lists have to be updated. Market Pricing Continuous Improvement (see Figure 7.4) provides a process for using market feedback itself for improving market-level pricing. It connects market-level pricing with price variance policy and execution, then uses measurements of these results to inform updates to the market-level pricing.

Figure 7.4 Market Pricing Continuous Improvement

Generally, market pricing is considered the province of product managers, yet, as with other areas of pricing, the entire pricing team should inform and be aligned with the market-level pricing. And generally, firms find they must update prices at least once a year, though some do it more frequently and other less.

Over the course of any year, the competition, targeted customer base, and marketing environments themselves will have evolved. Their evolutions can impact the firm’s pricing. For instance, some distributors will regularly update prices across the board with an index to inflation along with other, more targeted, price changes. In addition to changes in business strategy and exogenous factors, the firm may have improved or updated the offering or offering lineup, and these improvements or changes in the offering may warrant price changes.

Market pricing plans would have been implemented through price variance policy and the price execution levels. Information and measurements from these areas can be gathered to inform the results of the past cycle’s market pricing. And, the future cycle’s market pricing can use this information to update the plan and continue to drive performance.

While offering innovation pricing will often rely on direct market research, ongoing price updates can benefit from a new source of information: actual transaction pricing and sales. Some firms will use transaction data to identify optimal pricing for current products alone. Other firms will review transactional pricing information and supplement that insight through other forms of market research.

Regardless of the form of study undertaken to measure price capture and evaluate pricing effectiveness, market pricing reviews attempt to steer prices toward a more profitable or strategic point. Managers will be asking: Are the prices right? Does a new competitor or a competitive move necessitate a pricing action? Does a change in input costs enable a price improvement? Is a new market segment being attracted to our offering, and can we restructure and reprice that offering to better target the new segment? Does price variance policy need to be tightened or redefined? Thus, the measurements will focus on understanding the market reception to prices and price changes, competitive offers and prices, and new opportunities created through offering updates or new market openings.

Typical transaction data analysis for market-level pricing will include elements similar to those found in Price Variance Policy Continuous Improvement. These measurements are generally augmented with other data sources related to customers, competition, and the marketing environment. Supplementing these data sources may also be primary market research similar to the efforts done in relation to the offering innovation process, such as executive interview research, updating the model of the exchange value to customers, or conjoint analysis research across all product lines.

Through combining all of these studies, market pricing can be reviewed and updated with a solid fact base.

Symantec Inc., a leading desktop software firm, conducted market-level pricing reviews every year. In its market pricing reviews, the company gathers measurements from the results of a conjoint analysis in its dominant market, competitive information, currency fluctuations, and an index of price changes of similar and competing goods across countries, market share information, channel information, and website information. All of this information is used to update prices globally and update price variance and channel management policy. The result has been ongoing and healthy profits for decades, though many competitors have exited and many new competitors have tried to take Symantec’s place.

References

- D’Aveni, Richard. 1994. Hypercompetition: Managing the Dynamics of Strategic Maneuvering. New York: The Free Press.

- Deming, W. Edwards. 1986. “Out of the Crises.” Boston: MIT Center for Advanced Engineering Study.

- Smith, Tim J. 2012. Pricing Strategy: Setting Price Levels, Managing Price Discounts, and Establishing Price Structures. Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning.