CHAPTER 2

Rule Two

An Ounce of Execution Is Better Than a Pound of Strategy

The most critical responsibility of executives is to execute. Unfortunately, corporate leaders spend more time formulating strategy and less on execution. The businesses that achieve consistent profitability are usually led by executives who, first, manage an effective price policy (the strategy) and, second, ensure that the prices set by the policy get implemented well by the sales professionals and commercial teams (the execution). They make sure that the sales teams are well prepared with the right value conversations so that customers understand the prices as fair relative to the value the customer receives.

Would you rather have better strategy or better execution? It's a question that many leaders wrestle with, although in truth we are here to tell you that no leader has to make that choice. It's a false dichotomy. You don't have to choose one or the other. Well-prepared leaders can create the conditions for deploying equally successful strategy and execution. Yet because so many leaders believe they must choose one at the expense of the other, it's useful to dispel that myth. As always, the place to start in dispelling a myth is to define terms.

Strategy is all about achieving objectives effectively. Strategy is effective when it reflects an inspired vision of the future. At the C-suite level, strategic decisions include defining such fundamental “should” questions as:

- What business should the company be in?

- What competitive advantage should the company exploit?

- What capabilities that differentiate the company and its products and services should be pursued?

Execution embraces all those decisions and activities leaders undertake in order to transform the defined strategy into profitable commercial success. Strategy execution is the implementation of a strategic plan in an effort to reach organizational goals. It comprises the daily structures, systems, and operational goals that set your team up for success.

About 90% of businesses fail to reach their strategic goals. A sobering reality is that even outstanding strategic plans fall flat without effective execution, says Harvard Business School Professor Robert Simons, who teaches the online course “Strategy Execution.” His research concludes that failures of business strategy are always due to insufficient execution. “In each case, we find a business strategy that was well formulated but poorly executed,” Simon says.

Our main point is that while there are certainly trade-offs between strategy and execution, there is no conflict. Norman Schwarzkopf, the general who led the coalition forces in the Gulf War, knew that leadership requires a balanced commitment to strategy and execution. “Leadership is a potent combination of strategy and character. But if you must be without one, be without strategy,” Schwarzkopf said in 2012. Echoing the general, we say, “Business excellence is a potent combination of strategy and execution. But if you must be without one, be without strategy.”

Keep It Simple

One reason we think strategy is over-rated is that most models of strategy are just too complicated. Business managers can't understand multidimensional models of strategy and therefore cannot do an excellent job of executing them. Companies that have inspiring strategies that everyone understands do a much better job on execution. Consider Netflix. At one point, Netflix was in the mail order business. Users ordered a movie and Netflix mailed out a DVD. When users returned the DVD, they could order another one.

In 2008, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings made a strategic decision to exit the mail order business and convert to digital distribution. The timeline for the transition was five years. This decision led to an even grander strategic vision: Netflix would eventually be in the content business. The message to the stakeholders was simple and compelling. Now the challenge for Netflix was to execute on that strategy. Executives defined the digital distribution business, created a mission statement, hired the right team, set goals and timetables, determined fees, and, most important, established the right incentives. These were the activities Netflix required to produce results within the context of the strategy. Most analysts agree the execution was near flawless. That's one reason why Netflix is the world's leading subscription streaming service today.

One factor is that the managers charged with execution—the salesforce, commercial teams, customer service—rarely have the training or authority to question the strategy. They are incented to execute the plan whether it's right or wrong, whether it works or not. The most effective solution is to keep strategic plans simple and empower managers, the people closest to the customer, to question it.

Great Execution Starts with Outcome-Centric Thinking

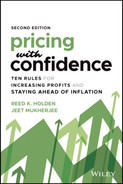

“It all starts with data.” This is a truism that most of our clients accept when the conversation is about analytics. We also argue that it all ends with data. Which is to say, the conversation begins with objectives, which then drive the analytics needed to generate insights to help accomplish those objectives and leads to desired outcomes. Underpinning this process is an understanding of the data that is required to do the analytics (Figure 2.1).

Too many times we have seen clients spend millions of dollars on data infrastructure and tools without considering what they will use it for. Instead, they focus on data visualization under the context of building visually improved dashboards that gives them visibility into all kinds of processes. For such cases, the analytics strategy, such as it is, has the goal of bringing together as much data as possible, creating limitless views of the data, and generating novel data-driven reports.

We argue that for most businesses with real problems to solve, such capabilities are useless. The views are untethered from consequence and the porting is typically used to manipulate data to support a decision that has already been made. Analytics uses data and math to answer business questions, discover relationships, predict unknown outcomes, and automate decisions.

FIGURE 2.1 Outcome-Based Approach

It's easy for businesses to misunderstand the cause and effect of analytics. They want to improve their decision-making and reduce ambiguity. That's certainly a laudable goal we support. But here's where businesses get analytics wrong. The drive to collect data must take a back seat to knowing the ultimate destination: a clear understanding of the decision or decisions they want to improve. At a minimum, this requires businesses to be able to name, describe, and model the business decisions the analytics is supposed to address.

That's challenging work, so it's understandable that the temptation is to assume that if a business accumulates enough data, filters it, puts it through an algorithm, integrates it, and displays it on a 100-inch screen visually, then the quality of decisions will improve. In fact, the ROI on such investments in analytics will be elusive. The resulting systems may generate reports in milliseconds and present the results in graphically arresting ways. But if a business hasn't defined the particular business decision or process to be improved, the more sophisticated the analytics, the more it adds to ambiguity.

It's easy to undermine analytics. In one of our projects, in response to the need to drive a well-defined business process, we developed a sophisticated reporting system. The VP of sales grew increasingly frustrated with the system because the profit margins it reported seemed to the executive insufficiently impressive. The executive ordered us to eliminate the 10% of transactions that represented the lowest margin for the business. The goal was to report more acceptable monthly profit margins. We find that analytics systems get undermined like this in all business sectors, at all levels.

Even in these times of low-cost storage and high-speed analytics at reasonable prices, we still live in a world of silos, which prevents us from truly extracting the value that sits right in front of us. We see situations play out when companies become reporting- or data-centric instead of outcome- or objective-centric and that departments start creating their own data sets for their own teams. An executive at one of the leading price optimization companies told us, “We still look at data in silos, be it marketing data, or sales data, or pricing data. We need to look at it as corporate data, so we can use it to get corporate intelligence.”

Limiting undisciplined negotiation on prices is a common outcome most companies strive for. Yet, there are rampant undisciplined negotiations where deviation requests are typically rubber stamped.

Why is limiting undisciplined negotiation on prices so difficult to achieve? The answer is that most businesses don't have a pre-determined action plan for the negotiation analysis they are performing. Most companies report on “depth” of negotiation on a transaction. Depth refers to how deep of a discount a sales representative gave for a particular transaction. The deeper the discount, the more likely for a conversation between a rep and a manager. Most of the time we don't see that conversation happen because the reports are ignored. On the rare occasions where such a conversation does take place, the rep invariably reports that “the customer was getting a cheaper price with a competitor, and I had to match that price.” The conversation usually ends there because the manager hasn't been trained in how to respond. The action plan with this example is not presented to change behavior. There needs to be a better assessment of competitive pricing for that negotiated product (e.g., a conversation with the product management team) as well as a program to train the sellers.

Simplify Analytics

It always amazes us to see how much time and effort clients put into “big data” analytics, but so little on insights that drive actions for business benefits. And the key to creating action from insights is to provide it at the time of need. Doing an analysis from two quarters ago is not as effective in triggering action as when the insight is given at the time of the transaction to change a behavior.

Insights can be driven off simple correlation models in Excel and pivot tables. It doesn't have to be a multi-factor regression every time. We had a SaaS client recently who had a differentiated product, and they based their pricing on 12 different variables to account for every case imaginable. The reason they called us was because customers were giving them feedback that they could not understand nor calculate their pricing. Big surprise. One of the analyses we did was a simple correlation model in Excel to see which variables were correlated to price. It turned out that they really could price based on just two of the variables. It was a drastic change, so they settled on three variables.

The point here, don't make things difficult because people will give your insights more validity if you use higher levels of math. Validity comes from insights generating an action to make the company money.

Elasticity Analysis Provides Insights

At the beginning of the pandemic, a client decided it was a suitable time to impose a significant, across-the-board price increase. In fact, it proposed a 100% price increase. The leadership asked for our endorsement of their strategy. Our instinctive impression was that the proposed price increase was risky and overreached, just as we started the pandemic lockdown.

We listened to the presentation. Their price professionals had done their homework. It was a very impressive presentation on the price increase and its expected impact on revenues and profitability. The presentation argued that the new products about to be introduced justified the price increase. As we followed along with the written presentation, we were struck by a detail in small type at the bottom of a page, almost as a footnote. The detail persuaded us that the proposed price increase was not only justifiable but could be defended as fair. We were struck by the results of the elasticity analysis. It was positive.

Price elasticity simply measures how demand changes as a result of a change in price. It is calculated by dividing the percent change in demand by the percent change in price. The relationship is usually negative. For example, when the fares for airplane travel go up, demand goes down. That’s an example of negative or “normal” price elasticity. With our client, we saw a rare example of positive elasticity. That is, demand had a positive relationship to price. The analysis concluded that if the client raised price, demand would actually increase, and it did.

It was clear that their customers needed the products under consideration; price was less of a consideration than reliable supply. That insight by itself was a good justification for the price increase. Yet there was one more detail. The confidence that the price increase could be called a “fair” price. Fair is an element of value, which is partially communicated in the elasticity analysis, but it's never enough.

To decide on whether to implement a price increase, the pricing department had done an investigation of competitors. The study demonstrated that competition priced their products dramatically higher. At the same time, the market rated the competitors' products lower in quality. For these reasons, the leaders decided that a 100% price increase could not only be justified but would be perceived by customers and salespeople as “fair.”

The theoretical part was well done. The client understood that even when customers secretly thought a price increase was justified, they would still complain. The execution included training of executives to make sure all the leaders agreed with the increase and to give them tools to respond to objections.

The next step in the execution was to collaborate with the account representatives for the top ten accounts. The agenda was to plan for what to do when the customers escalated their displeasure, as customers always will, up the management ladder up to, if necessary, the CEO. When the increases were presented to the test customers, we then evaluated their initial reactions and the arguments they used. We trained the salespeople to resist engaging with the customers' price complaints. Instead, we trained the salespeople to defend the price increase as fair based on the cost of providing the higher value and to do that during a global pandemic when many businesses were struggling with supply chain issues.

Through this training, the salespeople were persuaded that the senior executives were going to support the increase and expected them to do the same. What happened? The price increase stuck. There was no rampant discounting. Sure, some customers threatened to go elsewhere—and some actually did for a while—but most eventually came back and accepted the price increase.

Better Value Messages and Customer Targeting

One of the objectives of creating high-value impact messages is to identify customer triggers of value. These messages are critical when positioning a price increase. They are operational or profit-model characteristics that allow salespeople to qualify customer needs through simple questioning techniques. These triggers can be based on how a business is operated, what its central strategy is, or a combination of factors. Once these triggers of value are understood, they can be reduced to a compact list of questions that help salespeople identify high-potential prospects. The key is that the questions must be clear, direct, and result in concrete answers. We have found that salespeople welcome such tools.

We worked with one company that was providing a service to better manage printed marketing materials. The company built its business around increasing efficiency and reducing waste in the development, management, and distribution of such materials. In talking to customers about value, we found that they could reduce customer literature costs by 20 to 40% in the first 12 to 18 months of a contract. One of the qualifying questions to target customers may seem surprising: “How much dust is on your catalogs?” If printed catalogs in the storage room had a layer of dust, it was a good indication that the customer had printed too many catalogs, or their distribution wasn't professionally managed.

Once our client identified customers that overinvested in catalog pages that were literally gathering dust, it used its knowledge of customer value to present a clear, quantifiable, and relevant value proposition. Due to its efforts in researching customer value, the team was able to back up this claim with case studies and customer testimonials.

“We are able to reduce your costs by reducing obsolete inventory and by using our technologies to better match supply with your actual literature needs.” Now the team had a compelling opening step to prove value to their customers. “To show you what we can do for your business, we'd like to start with an assessment of your current approach to using and managing marketing collateral. We will provide a road map for significant improvements in the costs and effectiveness of your current processes and programs.”

By asking some simple questions the company began demonstrating financial impact for customers:

- “By using our service, did you see improvements in the management of your printed marketing materials?”

- “If so, what were those improvements and what was their impact?”

Now the company targeted the right customers with the right value messages and impact, and the business grew at a rate of 20% per year the next two years.

Identify the Customers You Can Serve at a Profit

Within the global view of markets, identify which customers and markets you cannot serve at a profit. If some customers are marginally profitable, but others are significantly more profitable, is your company better off serving the former, or are you better off focusing resources on the more profitable opportunities? It's a matter of defensive strategy. It's simply better for you that unprofitable customers are served by your competitors. It's one less burden for you and one more for them.

It's important to determine which doors you do or don't want your salespeople knocking on. If you don't identify these doors, salespeople will waste their time and sell to customers that don't value your offerings. Figure 2.2 shows that unfortunately, the track record B2B companies in customer targeting and selection is not good: 79% of B2B companies are undiscriminating, responding without analysis to all customers, according to research cited by Lion Arussy in his book, Profitable: Why Customer Strategies Fail and Ten Steps to Do Them Right (John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

FIGURE 2.2 Percent of Companies That Respond to All Customers

The 80/20 rule often governs this discussion. Also known as the Pareto Curve, the 80/20 rule says that, on the average, 80% of business derives from the remaining 20% of the business. As a result, we tend to focus on the big customers who drive most of the business. We let distributors manage the 20%. Is this a good strategy? Not always. Big companies are more than twice as likely to be price buyers, according to Holden Advisors research.

To better highlight the problem, cost accountants have developed what they call the “20-225” rule. Robin Cooper and Robert S. Kaplan, authors of Profit Priorities from Activity Based Costing (Harvard Business Review, April 15, 2000), have shown that once the cost of supporting customers is considered, only about 20% of customers are profitable. In fact, these 20% of customers account for 225% of the profits. Of course, this means that the other 80% of customers lose 125% of the profits. This principle applies equally to both private-sector and public-sector organizations.

The reality is that serving a sizable percentage of customers represents a loss for any business. The challenge, of course, is for a company to distinguish between the customers it can serve at a profit and those it cannot. It's like the time-proven adage attributed to department store mogul John Wanamaker more than a century ago: “Half the dollars I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is I don't know which half.”

In the case of distinguishing the profitable customers from the unprofitable, the first thing to do is go for the low-hanging fruit. Start by making a list of all your customers, from the most profitable to the least. Ensure that your most profitable customers get the lion's share of resources. Then focus on the 5 or 10% of your customers who are least profitable and fire them. These are the customers getting the big discounts but who fail to give you the big volume they invariably promised. These are the high-maintenance customers who the customer service department has on speed dial because they are so demanding. These are the customers who pay late. In other words, these are the customers who cost the company to service and keep on the books.

Firing them will do three things. First, it will increase your profits even though, at first, it may cost you some sales revenue. Second, it will send the signal to salespeople and customers alike that the company has pricing standards and is willing to stand by them. Your sales and customer service people will love you for it. Finally, it will free up your selling and service resources to pursue more profitable customers, who can add profits and revenue to the firm.

Because they are desperate for business, most managers will resist terminating customers. We don't like to do it either. The goal, of course, is to convert unprofitable customers into profitable ones. Before making a unilateral decision, we recommend that you have a candid conversation with the customers. Tell them why the relationship is not sustainable in its present form and let them know you are prepared to end the relationship. Some percentage of those bottom customers will understand and offer to keep doing business with you on renegotiated terms.

How Effective Are Your Price Discounts?

The essence of strategy is the efficient allocation of scarce resources so as to achieve maximum return. In other words, if you are going to do something as a manager, whether it is spending time, money, or both, for the sake of the company, you should have a basic understanding of what that expenditure is going to return in terms of added profits and added sales.

Consider the things you routinely do. For example, you attend meetings to discuss new products or more efficient operations—two important activities designed to increase sales and profits. If you are going to give a price discount, don't you want to be sure that the discount drives added revenue and profits for the company?

Limiting undisciplined discounting during negotiations is a common outcome most companies strive for. Yet, there is rampant discounting, and deviation requests are typically rubber stamped.

More than likely this is because most companies don't have a pre-determined action plan for the discount analysis they are performing. Most companies report on “depth” of negotiation on a transaction. Depth refers to how deep of a discount a seller gave for a particular transaction. The deeper the discount, the more likely there is a need for a conversation between seller and a manager. Most of the time we don't see that conversation happen because the reports are ignored; if we do, then the answer from the seller is almost always, “the customer was getting a cheaper price with a competitor, and we matched that price.” Then the manager walks away.

Here is what a true outcome-centric analytic process should look like for limiting undisciplined negotiation. First, determine if it's a behavior issue, a broken process issue, or if it is market driven. This process is required because the root cause determines your course of action. So, we would have three outcomes under negotiation and not just one.

For behavior issues, we recommend doing the analysis of seller negotiations by products and by customers (Figure 2.3) to see if they negotiate in whole percentages (e.g., 5%, 10%, 15%, etc.).

If we find sellers here, then the pre-determining action would be training and then monitoring for change. For broken process issues, such as discount approval rates north of 50%, which should trigger an investigation to understand the validity of the process in place, maybe we need to change the threshold for escalation, or maybe the manager needs more training.

FIGURE 2.3 Signs of Undisciplined Discounting

The market-driven scenario is the most difficult root cause to attribute. How do we determine if it is truly a competitive scenario? We have seen clients manage this in two ways. One, by having detailed reason codes that you can search on in CRM to determine how often and on which products this customer uses this as their reason. Two, we have also seen clients measure how often competitive price comes up in their daily reason codes and see if there is a deviation from the rolling average for a similar peer group segment. If there is a large deviation, then you know a competitor is making price moves on a particular product.

As you can see from the example of limiting undisciplined negotiations, analytics doesn't always have to have a data scientist involved to have business benefit. Your actions from your insights have already driven the value.

Control Discounting with Rules of Engagement

After your review of the outcomes from the discounting analysis, the commercial team needs to decide when it is clearly a mistake to give discounts. It may be with small customers. It may be with customers who purchase your high-value products and services and where you have little competition. It may be in certain geographic markets. It may be with salespeople who haven't been through value training. The team must identify where to give discounts and where to stop giving price discounts.

We call these rules of engagement. Simple rules of engagement are established to let salespeople and managers know that you are beginning to limit price discounts. At the same time, you let it be known that you are willing to let some business go. If you have done a decent job defining the rules of engagement, it shouldn't cost you valuable business. By that, we mean you hopefully have identified where it is wrong to be giving customer discounts. If they decide to leave, it is going to be good for your business. If a competitor takes them, it is great for you and the competitor suffers the deterioration of margins.

The trick to rules of engagement is to start with something easy. We have seen companies with all sorts of data infrastructure, from completely fragmented to a single source of truth and everything in between. Our guidance is that there is no data perfection. Start with customer usage and transaction data. Once insights are gleaned, decide what the right “budget” is for discounts per region per customer segment, etc. The rule of engagement should be that every customer that wants a discount must earn it.

Put teeth into the new rules of engagement, or you're wasting your time. Sales managers will just keep internally negotiating for more. One company we know reviews seller's discount performance on a yearly basis and fires their most extreme discounters. This kind of “rank-and-yank” strategy has other costs, but it definitely sends a message about what the organization values.

We have never seen strategy outperform execution. On the other hand, execution supported by a leadership team aligned on price policy will consistently outperform the limitations of strategy, structure, capital allocation, and even market conditions.