CHAPTER 4

Rule Four

Know Your Value

Value is the foundation of all business activity. Know it, own it, and prosper. The goal of Rule Four is to connect you in a fundamental way with the measurable value your customers have determined your offerings contribute to their go-to-market effort. If you can do that, pricing suddenly becomes more precise and transparent. If pricing is akin to playing poker, knowing your value eliminates the customer's capacity to bluff. It's as if you can see your opponent's hidden cards.

Why Value?

For what job is your customer hiring your product or service?

The late Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen used this question to get to the heart of what a customer wants a product or service to do. Customers “hire” your products to do a certain job that is to their advantage. That advantage, as determined by the customer, represents a clear channel to the question of how to measure the value that your offering delivers to your customers.

This book focuses on business-to-business (B2B) pricing. Business buying is more complicated than selling to consumers, where prices are more or less non-negotiable. It's unlikely that a consumer will ask the checkout clerk at Wal-Mart for a discount on a quart of milk. Understanding customer value is the core of B2B pricing. Businesses buy because they often convert what they buy into something they sell to other businesses. While the volumes can vary by a lot or a little, the impact within the operations of a customer's business can be dramatic. Understanding value is also important because B2B customers expect to negotiate. Sellers cannot defend price without understanding and having confidence in value.

The Power of Value and Use in Inflationary Markets

Basing pricing on value is the method of setting a price to earn a portion of the differentiated worth of its product for a particular customer when compared to its competitor. Customers buy a product or service to procure something of value in excess of what they have to pay for the product or service. Understanding that value helps you set a fair price for the product or service in question. Creating a culture that encourages salespeople to understand and believe in that value inspires them to be more confident in the sales and negotiating process. Creating alignment with a value culture is the critical success factor for senior leaders of any organization.

Value is king, even in an inflationary market. Think about being a customer and seeing a price increase on a product that you love to use. If that price is still below the value that you measure by using that product, then the increase is warranted. A price increase on a product where you are taking only a share of the value for your customers should be one of the first things you do in an inflationary market.

Conversely, anytime the customer concludes you are no longer priced fairly based on that value, it becomes more of a difficult conversation. The customer starts considering alternatives. In this situation, the most important questions to ask are, what are competitors doing, how sticky is this customer, how profitable is this customer, and what's my ability to change prices in the future?

We recommend pricing based of the value you deliver to your customer. The important note here is to set the price to invite the customer to capture value while ensuring you as the supplier capture a share too.

Adopting a Value Mindset

Understanding value comes from a business skill every member of your commercial team needs to cultivate: listening to customers without an agenda. Customers will happily give you the information commercial teams need to build critical insights about value, but not if they feel the team members have an agenda besides listening.

Such a listening tour does not have to be a big, complex research project. The most powerful insights usually result from asking direct open-ended questions and listening. In this information gathering mode, sales teams can be vital sources of wisdom. In fact, everyone who has contact with the customer at any stage of the sales and support cycles can engage with a value discovery mindset. Every opportunity for customer intelligence will have a beneficial impact for your own firm.

There is one question that we do not recommend you ask your customers. And that is, “What do you think of our prices?” Asking directly about your prices is an invitation for customers to posture. Every customer asked will agree that your prices are too high. Is that surprising? Your customers have every incentive to try to get you to believe this. Worse, this approach derails the conversation from its purpose.

The best questions center on their requirements and key problems that need to be solved, the benefits provided by your offerings, and how the two interrelate. The key is to understand your value to your customers and then use this information to support the fairness of your pricing. By showing that you understand your value and demonstrating that your prices are reasonable given that value, you change the discussion. It is no longer just about price; rather, it's about value and then price.

We recently did value research on a product that was sold to large financial institutions. We started with primary market research, which focused on getting an understanding of the benefit that customers would get from using the product. Only after we determined the value proposition did we assess customers' responses to a limited range of price increases. The benefit, or the value in this case, far exceeded the price that the research showed customers would accept. As a result, our client was able to increase prices, which were accepted without complaint by customers. It's a good example of how leveraging Rule Four resulted in increased revenues and profits.

Listening to the occupants of the C-suite requires a different approach than listening to procurement managers. For lower-level stakeholders, it's completely appropriate for listening teams to ask a series of discovery questions. Not so for senior executives. For senior executives, lead with insights, not questions. Your job at this point is to deliver value to executives while you glean insights from them. It's not for them to educate you on their business. Research and preparation are key. If you get time with any member of the leadership team, you should know their business and pain points and enter into a conversation which delivers insights into the opportunities, risks, and solutions they might not have considered.

Why Talk to Customers About Value?

Your customers are the greatest source of information on value and value based on their use of the product. This can be different for different companies, and value should not be one-size-fits-all. To investigate the details of how value is perceived, we recommend asking two questions:

- “What is driving needs and attitudes?”

- “What are the implications (for both the supplier and the customer) of addressing those drivers?”

By answering these two questions, we can answer an even more fundamental one:

- “Where, precisely, do we provide value in our customers' businesses?”

Without answers to these questions, companies are adrift. Businesses want to focus their resources on the best opportunities to provide financial value to their customers. And they especially want to concentrate on cultivating those areas where the business value can be differentiated from competitors. Gaining insights in these areas can have a profound impact on any business. It positions businesses to create even more valuable offerings, target the best customers for those offerings, and to empower their sales organization to sell value and defend prices.

For pricing confidence, it is critical to understand some fundamental aspects about customers, their businesses, and what it is they value. These insights achieve a number of important outcomes. The insights pave the way for better segmentation and targeting and the creation of offerings that are deemed by the customers to have value. The insights also serve as the foundation for well-defined price-value trade-offs (see Chapter 8, Build Your Give-Gets Muscle). Superior value positioning and better pricing are additional benefits of these insights. Figure 4.1 summarizes the power of understanding your value to your customer.

The progression of questions and objectives in Figure 4.1 underscores an unexpected point: the more you appreciate the value you deliver to your customers, the greater confidence the commercial team will have in the price. In this case, knowledge protects and can increase profits. But it gets even better than that. The knowledge cascades as part of a progression that sharpens your marketing strategy, product management, and sales techniques. It is with these activities that we create and frame our value to our customers. When firms apply their understanding of customer value in this way, positioning prices as fair relative to the value provided is quite simple.

FIGURE 4.1 The Power of Understanding Customer Value

Customers Want to Talk About Value

For the skeptics. The objection most frequently raised when we recommend asking customers about how they define value and how a supplier contributes usually takes this form:

Why would our customers share this kind of information? They'd be crazy to talk to us about how they make money and how our offerings help them make more of it. Won't they be afraid we would use that information against them? Won't they see this as a ruse to get them to give us the justification to raise our prices?

Our experience is that customers, as a rule, do not react like this to good faith questions from suppliers. Of course, customers must have some basis for trust. A long-standing partnership usually provides a foundation for trust. Commercial teams, in turn, must demonstrate that they are sincere in collecting the information for their mutual benefit. In other words, if the perception is that the information will help customers operate more efficiently, then customers may well appreciate the conversation. In practice, most customers are eager to talk about their businesses, their goals, and their efforts to be successful. Their motivation for doing so is simple. The more their suppliers understand their business issues, the better able those suppliers will be to craft solutions that are relevant and valuable.

It takes good listening and probing skills to gather this information. It also requires shifting your point of view from an internal perspective (a focus on the value you believe you deliver) to an outside-in perspective (the performance, benefits, and value as perceived by your customers). Only the latter view counts, as the customer determines value.

There is one final consideration. The analysis must be done in the context of your specific competitors. Customers always consider solutions in the context of competitors. No business operates in a vacuum. When customers think about suppliers, it's usually in the framework of how one performs relative to competitors.

One of our clients produces heavy equipment. Its value challenge was that there was little differentiation between its products versus a key competitor. As much as 80% of the equipment components were common to the competition. Given this commonality, the industry was racked by cutthroat price negotiating and discounting. Our job was to establish a basis for the client to defend its pricing. We started by interviewing the client's customers to determine if there were points of differentiation we could leverage. The initial plan was to conduct 30 customer interviews in each of nine segments.

Over the course of just the first six interviews, we gained enough information to show our client that its products provided demonstrably more value than the competition. When our client's most important customers talked about what they appreciated about our client's business model, they had a common response: The value of their dealer network. This network was almost twice as large as the next largest supplier. The customers saw over and over again how the scale of the dealer network reduced downtime, decreased operating costs, and kept revenue-producing assets in the field.

If a customer, for example, needed a critical part and its local dealer didn't have any in inventory, the part could be obtained very quickly from another dealer in the network. With just a handful of interviews, we learned that customers perceived an incremental value of 15 to 20% buying from our client products relative to buying a similar product from the competition. Our client used that information to focus its marketing efforts and defend its prices.

How Does the Customer Obtain Financial Value from the Use of the Offering?

When talking to customers the goal is to drive the discussion to a dollar sign. Dig deep for financial value, otherwise any talk about value to the customer is just noise (Figure 4.2).

We were collaborating with a company that offered a wireless infrastructure solution. During their initial internal discussions, the IT and services people focused exclusively on the technology of the product. Their comments focused on the technology, process, design, and integration services that they delivered to their customers. These elements are important, but they are not what the customers wanted to talk about.

FIGURE 4.2 Connecting Features to Benefits to Value

Customers were more concerned about geographical coverage of services, uptime, and reliability of the platform. With coaching, the supplier team learned to demonstrate how each of the features cited by technical staff focused and aligned with the benefits that the customers wanted and what subsequent financial results were realized.

The financial connection comes from a process we call drilling down during internal and external interviews. This is the tactic of probing to uncover the details underneath the customer's first answer, which is often superficial. The drill down generates critical value insights because it moves well beyond the cursory or top of mind answers that most customer research yields.

We were working for a software company interviewing the CEO of a systems integrator. When we asked the executive why reliable messaging was so important, the executive answered that half of the company's technical support budget would be saved if the company had reliable messaging. The bottom line is that we were able to determine that if they had reliable messaging in their software tools, the firm would save $300 million in technical support and software development expenses. Getting to why represents the best opportunity to provide a quantifiable ROI for selling the right offering.

The information-gathering effort required curiosity and a willingness to ask simple open-ended questions and then listen. This last point may be the most difficult because listening without judgment or preconception is not easy. This process is not difficult for those firms that want to do a better job of understanding their customers. The constraint is that many managers find themselves bogged down in day-to-day activities to accomplish these tasks with customers in mind.

Customer Interviewing

It is important to prepare well-thought questions to conduct interviews. There are three distinct steps to think about: preparation, execution, and integrating results.

The technical term for the actual interview is exploratory depth research. It is exploratory in that it uses your insights to develop hypotheses about how your customers value your products and services. Through multiple interviews, the hypotheses are confirmed or revised. It requires an in-depth interviewing approach in that probing techniques go beyond superficial answers. Ideally, it surfaces real points of pain your customers have and what they value when looking for a solution. The goal is to find out how product or service features reduce costs or increase prices and sales. These are the real value drivers of a business.

When doing depth research with a client's customers, we find:

- The real drivers of customer value are somewhat different than the selling firm expected.

- The current solutions are more valuable than estimated by the supplier.

- Customers are pleased that someone is finally asking them about their business in a meaningful way.

- There are opportunities to provide much more value than suppliers currently offer.

To transform the information into real insights you need to summarize the key points, important customer quotes, and financial implications from each interview. The important thing is to keep track of your insights on customer value drivers, possible value positioning, competitive value positioning, pricing, and possible product or service enhancements. This library is powerful for making value real for sellers and should be kept up-to-date to help create case studies to support your value over time.

We helped a supplier of business forms conduct this process in the banking industry. At the time, this supplier offered 150 individual services on an ad hoc basis to its customers. Many of these services were provided on request without charge. Based on the customer interviews, our client discovered that a majority of the banks identified a specific bundle of these services as especially valuable. The client was further amazed that the bundle of services cut across a number of banking segments that were otherwise ignored in their models. In fact, they found that they could dramatically simplify their service offering and start charging for that service bundle. The client was leaving money on the table by not recognizing the value of these services.

FIGURE 4.3 Using Customer Value to Simplify Offerings

As a result of these insights, the client rationalized the bundle into 10 segmented service packages, each priced accordingly. The offerings also included a bare-bones basic service package (see Figure 4.3). When the services were rolled out, the supplier reversed a 5% per year decline in profitability and began growing at 5% per year in a declining industry. Much of this success can be attributed to the fact that the connection between the customer's business model and their high-value needs was easy for the sales force to implement. The sales team asked each prospect three questions about their business and how they planned to grow. With the answers to these questions, the seller was able to quickly select the best offering for the customer and position it with concrete value statements.

Simple and Consumable

Over the years, we have interviewed the salespeople, and they admit that they just didn't trust the black box value calculations. We listened closely and concluded that the best value analysis must be simple and consumable for salespeople. Our guide is to make it simple enough that it can be displayed on the back of a napkin.

A few years ago, we were asked to do a value study for a large medical device company. They had a device that was disposable and would replace a popular non-disposable device in use around the world. The advantage our client offered, unlike the incumbent device, which needed extensive cleaning before re-use, was that it was a disposable device and didn't require cleaning. A problem of the incumbent device was that if it wasn't cleaned properly, the possibility of cross-patient contamination was present.

The medical device company engaged several of the larger consulting firms to do extensive value work that resulted in detailed, complex spreadsheets to determine the pricing of the disposable device. It was all detailed down to the tenth of a cent. When we saw the spreadsheet, we were impressed by the sophistication of the calculations. At the same the calculations measured the wrong thing, and the sales team did not want to use it.

The medical device company had targeted large teaching hospitals as prime targets but were struggling to gain adoption. To help increase the velocity of adoption, we identified the underlying problem. The focus was on the wrong target customers. It came down to the value advantage perceived by the customers. Large teaching hospitals tended to have excellent programs to train people on how to clean the devices. The likelihood of cross-contamination of patients was extremely low and therefore not a concern to the hospital team. Adoption was low because the company focused on the wrong market cohort.

We suggested that smaller hospitals, which didn't have the highly effective training programs, were likely to be more logical adopters. We further suggested that hospitals that serviced immunosuppressed patients were even higher in their likelihood of purchase, as cross-contamination would be viewed as a critical issue. These hospitals would be expected to see value in disposable devices that would eliminate the possibility of cross-contamination. The value for this product was in risk mitigation.

The trick to understanding value is to try to put that understanding into a series of back-of-napkin calculations that help salespeople and customers see how the features of your products and services create value for your customers and their products. Our change of heart proclaims this takeaway: you are better off being approximately right than precisely wrong.

To summarize, link how your product and service features create benefits for customers and the benefits of that value in specific financial terms. Make sure to connect the dots. We see a lot of companies that stop at the benefits, expecting customers to make the final linkage to financial value.

Capabilities Needed for a Value Focused Organization

Pricing clarity comes into focus when commercial teams connect with the measurable value offerings contribute to the go-to-market effort of the customers. Every successful business must offer a product or service that differentiates itself from the competition. The most successful businesses are intensely customer-focused, in that feature sets and improvements are based on the customers' wants and needs. Another critical way that businesses express differentiation is through pricing. It follows that customer-focused pricing becomes a strategic response to the customer's perceived value of a product or service. Businesses that offer unique or highly customized features or services that are aligned with the expressed desires of their customers are simply better positioned to defend their prices.

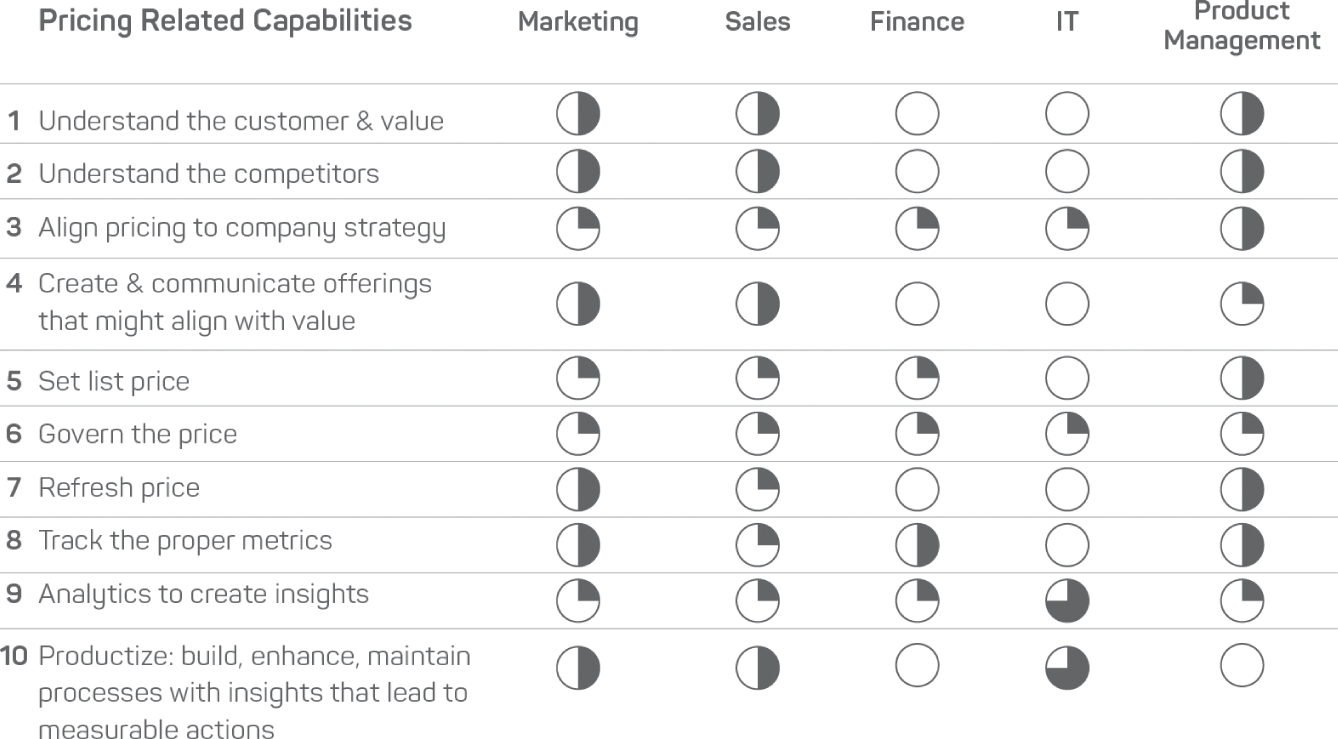

Figure 4.4 presents a capability matrix which is needed to support all pricing activities. As you can see, no one function is at a level required to be consistently effective for value-based pricing.

One risk with parsing these needed capabilities across different departments is the likelihood for unhealthy and conflicting prioritization of activities within functions. This means the pricing team would spend most of its time negotiating with functional leaders to gather the right information rather than executing on the end goals. This wastes time that you don't have in a volatile market.

FIGURE 4.4 Pricing Related Capabilities Matrix

Another structural design flaw we see are smaller pricing teams spread through different functions across different regions. These teams tend to be specialized for local and department needs. Silos are an unfortunate effect of such localization. No one person is charged with supervising the company's interest holistically. Deal profitability is parochial, and sellers focus only on specific product lines by region.

To develop effective pricing—to achieve pricing with confidence—it's important for companies to develop all 10 capabilities identified in Figure 4.4. For that reason, we most often recommend that the pricing team be centralized. The only caveat here is that for a conglomerate with disparate product offerings and/or markets served by the individual companies, it often makes sense for pricing responsibilities to be dispersed.

Because pricing is a strategic lever for organizations, most have found that the pricing reporting structure should be into the C-suite. The pricing team needs to have influence and ownership. What's more, the pricing team needs to be seen throughout the organization as having influence. Reporting into the C-suite provides the pricing team with the gravitas to be successful in achieving the end goals. Having said this, any pricing organization must be horizontal in its approach. Meaning, it needs to collaborate like a team sport with multiple functions to achieve those end goals. A pricing director of a large global electronics manufacturer told us that pricers need to be “multi-lingual,” that is, they are able to speak finance, IT, marketing, operations, and, of course, sales.

The Behavioral—Social—Dimensions of Pricing

This book focuses on the tactical and strategic dimensions of pricing. Yet we would be remiss if we didn't address the behavioral dimensions of pricing because, stated as directly as possible, pricing is a group decision. Pricing in an enterprise context incorporates the group decision dynamics of pricing committees, pricing departments, and ad hoc pricing teams. Furthermore, the agendas of executives aligned with the interests of various functional departments (finance, marketing, accounting, engineering, sales, production, etc.), each with adjunct responsibilities for price-setting, must be included in the mix, underscoring the essentiality of group dynamics around pricing. As Gerald Smith, a business professor and chair of the Marketing Department at Boston College in the Carroll School of Management, noted, “With so many voices involved in price-setting, there is an important imperative: to understand ‘how pricing gets done around here—socially.'”

The pricing department, group, or team should be at the center of price management activities harnessing the data diversity and decision diversity resident in corporate functional departments. As Smith noted in his influential book 2021 book Getting Price Right: The Behavioral Economics of Profitable Pricing (Columbia Business School Publishing), resolving the social parameters of pricing requires managers to ask some fundamental questions about group dynamics:

- Who engages in pricing?

- Who is influential?

- What biases are present?

All these questions and biases determine how a team goes about price-setting. Biases are often driven by the “functional nations” from which managers have been trained, each with a different professional culture, different language, different key performance indicators (KPIs), and different ways of approaching pricing. “Where the managers identify—Finance, Accounting, Marketing, Sales, Production, Engineering, and Pricing—help determine the values, priorities, and prerogatives that determine pricing,” Smith said.

“Still, these diverse organizational departments offer valuable data and skills that are vital to price-setting. For most firms, according to Smith, the key to achieving profitable pricing is to focus on two cognitive pillars that should undergird the pricing decision process: data diversity and decision diversity across the price-relevant domains of the organization. This means tapping continuously into the influence perspectives from the four cardinal pricing orientations (Figure 4.5) and their champions within the organization,” he said.

“Doing so exploits the price-relevant skills—both soft and hard—of each of these different corporate functional nations, while debiasing the price-setting process with a constant awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of each—a system of checks and balances if you will that leverages decision diversity,” Smith said.

FIGURE 4.5 The Four Cardinal Pricing Orientations

Companies exhibiting sound pricing discipline use their pricing departments or groups to achieve a balanced pricing orientation. For example, Adobe reframed its pricing strategy in 2012 using subscription pricing, a major shift in pricing strategy. Quite apart from the administrative effort, what really impressed us was the coordinated effort across the finance, accounting, engineering, marketing, and sales functions that resulted in such an effective, coordinated shift in pricing strategy. Professor Smith describes a corporate boardroom converted into a new pricing “war room” with its walls posted with the most up-to-the-minute pricing analyses, updated continuously with feedback from each of the functional price-relevant disciplines. The transition to the new pricing strategy took five years from initial launch with constant refining, adjusting, and listening to customers to arrive at an emergent pricing strategy.