CHAPTER 7

Private Equity Compliance Technology, Business Continuity, and Cybersecurity

7.1 INTRODUCTION TO THE ROLE OF TECHNOLOGY IN PRIVATE EQUITY COMPLIANCE

Technology has played an increasingly important role in the management and operations of private equity firms. This is true across all aspects of a private equity firm's business, ranging from investment management through to operations. As technology has evolved it has also played an important role in influencing compliance management at both the general partner (GP) and fund level.

Increasingly GPs have devoted more of their compliance budgets toward technology-related initiatives. Similarly, the resources of a private equity firm's information technology function and associated budgets are increasingly focused on compliance-related tasks. There are a number of reasons for this. First, as noted earlier, with technology come a number of process efficiencies that GPs and their investors can benefit from.

Second, limited partners (LPs) who invest in private equity do not typically focus exclusively on this asset class and also typically allocate to other types of alternatives investments such as hedge funds and real estate funds as well as traditional fund managers. This is particularly true of large institutional investors such as pension funds and endowments and foundations. Other areas of the asset management industry have been strong adopters of information technology–related compliance initiatives. This has been particularly true of heavy users of technology to facilitate compliance oversight of funds that execute large volumes of trades, such as high-frequency-trading hedge fund strategies. As investors have seen the ways in which these other asset managers have embraced technology in all areas of their firms, including compliance, they have increasingly pressured private equity managers make similar technological improvements in their firms.

7.2 REGULATORY FOCUS ON TECHNOLOGY COMPLIANCE

Regulatory agencies that oversee private equity funds have increasingly focused on the role technology plays. This includes providing guidance on the ways technology should be utilized and a focus on technology-related expense management.

7.3 CYBERSECURITY COMPLIANCE IMPLICATIONS

While technology has afforded GPs and their investors a number of benefits and efficiencies, it has also brought with it a number of new and increasingly complex challenges. One area rife with the greatest potential risks is cybersecurity. Cybersecurity is a broad term without a single universally recognized definition. Practically, it can encompass a wide variety of considerations and risks, depending on the context.1 For the purposes of our discussion, we will define cybersecurity as the risks associated with maintaining the integrity of a private equity firm's information and architecture, with a focus on protecting data and intellectual property from unauthorized access or theft. Cybersecurity-associated risks include unauthorized penetration into a fund's computer systems and theft of data by the firm's own employees. In this chapter we will focus on the compliance implications of cybersecurity risks as they relate to private equity investing.

7.3.1 Penetration Testing

Penetration testing is a series of testing procedures which simulates the attempt by a bad actor, such as a hacker, to breach the integrity of a GP's data security architecture. Once inside the network of a GP, a hacker could perform a number of different malicious acts, ranging from the outright theft of proprietary GP data and secrets to installing malware to cause damage to a firm. Penetration testing may be performed:

- Through the use of in-house information technology personnel

- By third-party vendors

- By a combination of in-house and third-party resources

Each of these approaches has different benefits and drawbacks. For example, an in-house-performed penetration test utilizing existing resources is likely more cost effective as compared to engaging a third-party firm. The drawback, however, is that a third-party vendor that specializes in this area would likely have a better understanding of industry-wide best practices with regard to information security and testing in this area. Furthermore, cybersecurity is often a fast evolving area with a need for remaining up to date on current technologies and their weaknesses and updating patches to fight off unwanted attacks.

It is generally considered best practice for a GP to utilize a combined approach whereby the work of third-party specialists is complemented by in-house resources that perform related cybersecurity work, such as ensuring that any software update patches that may repair vulnerabilities are appropriately installed.

In practice such patches themselves are not always entirely effective as in some cases the patches are not released by the manufacturers of software until after they have been exploited by hackers. This was the case with a widespread ransomware attack called WannaCry in 2017, launched by North Korea.2 This attack affected firms in many industries, including financial services, and was a special type of attack called a computer work that exploited weaknesses in the Microsoft Windows operating system.3 Ransomware is a type of criminal cyberattack where the attackers effectively block an organization from accessing their own data and then require a payment in order to provide the user with the ability to re-access their own data.

As it relates to compliance, penetration testing is important not so much because of the actual testing being performed but rather for the potential vulnerabilities that a penetration test can reveal. The best way to illustrate this is through an example. Consider a situation where a GP's network is penetrated by a third-party hacker. This hacker steals sensitive personal information about individual LPs and then sells it on the dark web to other hackers, who utilize this information to expose financial information about the LPs. In this case, although the GP obviously didn't want this to happen, weaknesses in their network allowed the hacker to cause damage to the LPs. In addition to potential violations of privacy laws and exposure to action from regulatory agencies, the GP may also be financially liable to LPs for all or a portion of the damage done to LPs. A penetration test may not have prevented the hack as described in this example; however, had the GP performed this test they likely would have been much more prepared than if they had not performed this testing.

7.3.2 Vendor Cybersecurity Risks

Traditionally, a private equity fund manager's information security efforts focused primarily on the risks present at the GP. Increasingly there is an acceptance of the realization that cybersecurity risks at service providers to both a GP and their associated funds can also present significant information security vulnerabilities.

One common technique utilized by hackers to exploit cybersecurity vulnerabilities at vendors involves a technique known as phishing. Phishing is a type of social engineering cyberattack where a bad actor impersonates a legitimate information source in order to fool someone to act on the attacker's behalf or to try to steal valuable information. Phishing schemes in the fund management industry are commonly executed through email. A specialized form of phishing is known as spear phishing. Spear phishing involves an attacker performing significant research in order to specifically target security weaknesses. Based on the amount invested in crafting these spear phishing attacks, they commonly target individuals or companies where highly valuable data or large financial sums can be stolen. This includes fund managers such as hedge funds and private equity funds.

In some instances in spear phishing attacks, hackers utilize misspellings of legitimate domain name extensions in an attempt to fool a GP's employees or vendors into believing that the correspondence is coming for a legitimate party. An example of this allegedly occurred in 2016 in the case of a commodity fund manager named Tillage Commodities, LLC (“Tillage”) and its fund administrator, SS&C Technologies (“SS&C”). In that instance Chinese hackers allegedly utilized a practice called domain spoofing. Under this practice, legitimate domain names are misspelled, typically in minor ways, in order to appear legitimate. In this case Tillage alleged that the Chinese hackers utilized spoof domains to fool SS&C into initiating fraudulent wire transfers. Specifically, in a lawsuit against SS&C, Tillage alleged that the hackers added an extra l to the correct name of Tillage's email domain in order to make it appear as if the hackers were legitimate. Therefore, instead of “tillagecapital.com,” the fraudulent emails used a domain name with one additional l (i.e. “tilllagecapital.com”).4 The aspect of the Tillage situation regarding considerations for GPs to draft compliance policies to incorporate the role and oversight of service providers such as fund administrators, and potential regulatory liability for not doing so, is addressed in Chapter 10.

7.4 DATA ROOMS

A data room, sometimes also referred to as a virtual data room, is a common tool utilized by GPs to archive and exchange data. This term does not refer to a physical room where information is stored but instead a software-based repository that is often cloud based and accessed through the Internet.

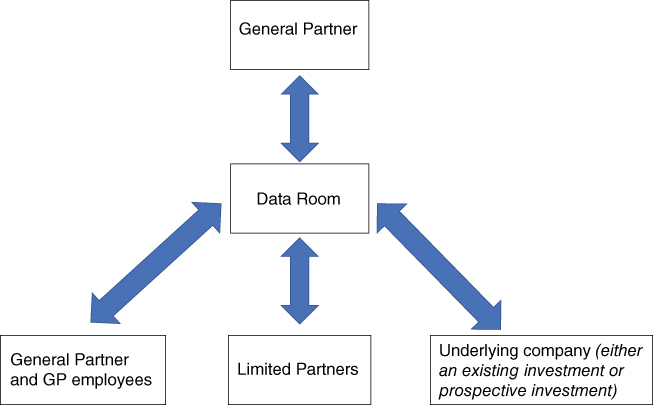

Data rooms have increasingly risen in popularity as data room technology has continued to become more readily available and affordable. While not every GP may utilize data room technology there are a number of compliance benefits that they may provide. There are three primary uses for data rooms. The first instance relates to situations in which the GP shares data with LPs at various stages of their investing lifecycle. The second instance is where data is shared among the GP and underlying companies that it is invested in or that are being considered for investment. The third way in which data rooms are utilized involves the GP storing and sharing data among its various employees.

In these last two instances it should be noted that data may flow in each direction. That is to say, the GP itself may be the one initiating the data transfer through the data room, or alternatively, data may be uploaded by the other parties (i.e. from the LPs, underlying companies, or GP employees) for review by the GP. These situations are summarized in Exhibit 7.1.

Exhibit 7.1 Three common private equity general partner uses of data rooms.a

aDouble sided arrows indicate that data may flow in either direction.

We will address each of these situations in more detail and discuss the compliance considerations and challenges a GP may encounter in each data room usage situation.

7.4.1 GP Sharing Data with Limited Partners

GP's share data with LPs at two primary points in their investment lifecycle. The first is during the GP fundraising process, when a LP has not yet committed capital to a fund. At this stage LPs are referred to as prospects or prospective investors.

When dealing with prospects, a key compliance consideration GPs must take into account relates to drawing a distinction among what types of data LPs should be sent. Certain information is required by law to be provided to prospective investors. This is called required documentation. A common example of required pre-investment documentation that all LPs must be provided with is the fund's offering memorandum. The second type of data provided to prospects would be what is known as optional data. This information is not necessarily required to be provided by GPs, but they may provide it for a number of reasons.

An example of how optional data functions would be if a prospect were evaluating a potential investment in a GP's fund. The prospect would likely request documentation beyond that which is required during a process known as due diligence. An example of the type of documentation an LP may request could be a due diligence questionnaire prepared by the GP or the previously audited financial statements of a prior vintage fund operated by the GP. Continuing this example, while the GP may readily provide the due diligence questionnaire requested by the prospect in their discretion, the GP may make the determination that they would not like to share the prior audited financial statements for a different fund. This could be because the GP felt that historical financial statements from previous funds were not relevant to the current fund that they were raising capital for, or they simply did not want to comply with the request. While a deviation from market practices, technically there would be no specific law that would require the GP to provide this information; therefore, under our example this could be classified as optional data.

This is not to say that the offering memorandum of a fund is the only document required to be provided by GPs to prospective investors. Indeed, other documents, including those without as much legal jargon such as due diligence questionnaire or marketing presentations, may be required to comply with other notions, including ensuring appropriate transparency and sufficient disclosures; however, the extent of such required documentation distribution must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and would not typically be spelled out as a bright-line rule by any law or regulatory guidance.

From a compliance perspective, GPs must generally fulfill a number of requirements relating to tracking the data provided to prospective investors. First, once they have determined what data is required to be provided to LPs, they must indeed ensure that LPs receive this data. As noted, rather than transmit this information to LPs in hardcopy or through other electronic media, data rooms are increasingly utilized in the private equity industry to fulfill this purpose. The way this would work in practice would be for the GP to upload the required documentation, as well as any optional documentation, to the data room. These documents would then remain on the virtual shelf in the data room.

When dealing with a prospective LP, the GP would then invite the prospect to the data room. This is typically done through a password-protected and encrypted system. The LP would then have the ability to access the documents from the data room. To be clear, the LP cannot edit the documents in the data room. As noted above, the GP may limited which documents an LP can access while maintaining a larger set of documents on file in the data room for other purposes, such as to share internally among the GP employees.

The reason data rooms are helpful to GPs is that on the backend of the data room technology, data rooms facilitate compliance recordkeeping requirements. One way they do this is providing a paper trail at each stage of the process. For starters, the GP would have a record of when the LP was invited to access the data room. Then the GP would similarly have a record of not only which documents the LP had access to, but also which documents they accessed online and downloaded as well as when these actions occurred.

Another feature of data rooms that assist with private equity compliance recordkeeping requirements relates to concepts known as document labeling and document numbering. Document numbering is also called serialization. As noted, financial regulators often require GPs to keep detailed records of which documentation was provided to prospective investors. A common practice that has evolved in this area is for GPs to create a number system for different documents. For example, the first offering memorandum distributed to a prospective investor for a new fund could be labeled “Number One” on the front page of this document. Typically, these labels would be inserted electronically into the document. The second offering memorandum distributed to a second prospective investor would be labeled “Number Two.” This process would continue with sequentially increasing numbers for all offering memorandums that were distributed. While this may seem fairly straightforward, throughout the fundraising process the initial version of the offering memorandum may undergo a series of updates. One common reason for this could be based on feedback on certain fund terms from investors.

Once the GP decides to make these updates they need to ensure that all prospective LPs are provided with access to these changes. This could involve editing the original offering memorandum or keeping the existing one in its original format and issuing an additional amendment document known as a supplement. In either case, a single investor could receive multiple versions and supplements of an offering memorandum throughout the GP's fundraising process.

Prior to the use of data rooms, the records of which LPs received what documents would have been kept either in hardcopy or in a kind of electronic ledger such as Microsoft Excel. Data room technology can automatically place numbers on documents and keep track of which LPs receive what data.

A similar concept to document numbers relates to document labeling. This involves a process whereby a specific LP's name, or other piece of identifying information such as an email address, is placed on the documents she is receiving. This is typically known as a watermark, and helps to ensure that LPs receive the documents that were intended for them and not another LP. Watermarking also facilitates document security and tracking. For example, if a GP document were exposed via a hack and uploaded to the Web, or in some other public forum, then the electronic watermark would allow them to track down the source of the documentation.

After an LP decides to allocate capital to a particular fund, the GP typically has an additional series of documentation that is shared with LPs on an ongoing basis throughout the life of the fund. One example of this would be a quarterly update from a GP regarding the performance of the fund's investments and the value of the LP's investments in the fund. This type of document could also be distributed by a GP through a data room; this would be similar to the ways in which information was distributed on a pre-investment basis to the LP. The facilitation of LP tracking of access to documentation as well as document number and labeling are ways in which GPs implement compliance oversight of the document distribution process to both prospective investors and existing investments through data rooms.

7.4.2 GP Sharing Data with Underlying Companies

The GP may also utilize a data room to facilitate the collection of documentation from portfolio companies. When dealing with underlying companies, private equity firms have a number of compliance obligations requiring them to keep appropriate records of their due diligence and ultimate investment activities.

Similar to the two main stages at which the GP works with the LP, the GP deals with underlying companies at the same two stages: pre-investment and post-investment. The difference in this case is that an investment is not being made by the LP into a fund managed by the GP, but instead the GP is considering an investment in an underlying company.

When the GP is conducting due diligence on a portfolio company being considered for investment both the GP and portfolio company may require certain documentation, such as a nondisclosure agreement to be executed prior to the start of the due diligence process. These types of documents may be shared and stored in a data room.

Once these pre–due diligence documents are in place, the GP may then request a series of documents to facilitate their analysis of the underlying portfolio company. Examples of these types of documents may include financial, legal, and various types of investment and operational information. In these cases, one of two scenarios could occur. The first would be for the GP to create a special data room focused around document sharing between itself and the underlying company. This can be referred to as a deal-specific room. The second alternative would be for the portfolio company to set up its own data room, similar to the one a GP would set up with an LP. In this case, the data room would be administered by the portfolio company instead of the GP.

Due to the recordkeeping compliance obligations of GPs referenced above, the more common scenario is for the GP to create their own deal-specific room as opposed to the latter alternative.

After a GP has made an investment into a portfolio company there is a series of regular documentation and reporting that the GP will often require from these companies. Examples of this would include cost and profitability information to facilitate managing the investment by a fund managed by the GP into the fund. The collection of this data, as well as the sharing of any data by the GP with the portfolio companies, is also typically performed via a GP-hosted deal-specific room.

7.4.3 GP Sharing Data Among Its Employees

The third common way data rooms are utilized by GPs is to share information among their employees. This may be accomplished via a data room application or through an internal shared drive. In either case, from a compliance perspective the important thing is that the GP must comply with requirements relating to the retention and archiving of records throughout their firm.

7.4.4 Business Continuity Planning and Disaster Recovery

Business continuity planning and disaster recovery (BCP/DR) is an area of increased importance for private equity funds and represents another key area in which the compliance and IT functions overlap. Business disruptions can occur for a wide variety of reasons. These range from the more commonplace disruption in utilities, such as phone service, Internet connectivity, or power outages, to more widespread disaster events, such as terrorism or extreme weather.

While it is a good business practice to ensure that a private equity fund can continue operations in the event of disruption, increasingly regulators are also mandating that private equity funds develop written business continuity and disaster recovery policy documents that outline a private equity fund's plans to deal with BCP/DR events. As an example, in the United States, the National Futures Association (NFA) Compliance Rule 2-38 requires funds registered with the NFA to adopt business continuity and disaster recovery plans.

Another example is the guidance provided by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with regard to Rule 206(4)-7, which outlines in part:

We believe that an adviser's fiduciary obligation to its clients includes the obligation to take steps to protect the clients' interests from being placed at risk as a result of the adviser's inability to provide advisory services after, for example, a natural disaster or, in the case of some smaller firms, the death of the owner or key personnel. The clients of an adviser that is engaged in the active management of their assets would ordinarily be placed at risk if the adviser ceased operations.

Increasingly the compliance function is providing insight into the design and oversight of a private equity firm's BCP/DR plans. This is not only to comply with regulatory guidance in this area but also to promote the ongoing oversight and integrity of the GP's operations as well as facilitate data sharing and archiving as referenced above. When designing a firm's BCP/DR policy documents key areas typically addressed in a BCP/DR plan include:

- Data backup and recovery.

- Developing communication plans so key employees can communicate in the event of a disaster event, including the use of tools such as a calling tree.

- Clarification regarding the process by which employees can continue to work while outside the office. This can include details of remote employee secure access and the ability to continue trading via alternative measures, such as using mobile phones.

- Designating alternative locations from which employees may continue operations. This includes designating a formal location, known as a disruption gathering location, where employees would be directed to go in the event of disruptions that render a private equity fund's office inaccessible.

- Details of how communications with investors and fund service providers should continue in the event of a business disruption.

- Does the firm maintain written BCP/DR procedures? If yes, what is the scope of such procedures?

- Has the firm customized its business continuity and disaster recovery plans or is a generic plan in place which may not address the operational aspects of the firm?

- Are any written BCP/DR plans structured around industry certifications or guidelines?

- Do BCP/DR plans cover multiple scenarios, including inaccessibility of the firm's offices?

- Do BCP/DR plans provide for coverage of plans for outages of telephony and Internet loss?

- Who oversees updating the plans?

- Are employees provided with contact information for each employer in a manner that is not linked to the firm's systems functioning properly (i.e. such as a laminated calling tree card)?

- Backup power:

- Are uninterruptible power supplies (also uninterruptible power sources [UPSs] or battery/flywheel backup) in place? If yes, are UPSs available for desktop PCs and servers?

- How long do UPSs provide power?

- Does the firm have backup power-generation facilities? If yes, what type of generator (i.e. diesel, natural gas) is utilized?

- Who is responsible for maintenance of such devices?

- If backup power-generation capabilities are in place, does the firm own such devices exclusively or are they shared among other firms?

- Data backup and restoring:

- What are the firm's data backup capabilities?

- Is data backed up in multiple locations and via multiple media?

- Is data stored onsite, offsite, or both?

- Is a separate backup facility maintained for data storage?

- Has the firm performed test restores from any backups?

- How long would it take the firm to perform a data restore for system-critical functions in the event of a disaster?

- Does the private equity firm have a disruption gathering location?

- Does the private equity firm maintain a separate facility from which employees may continue operations? If yes, how many seats are in such locations?

- Has the private equity firm ever had to activate its BCP/DR plan? If yes, what happened?

- Who is responsible for activation of the BCP/DR plans? How is plan activation communicated to employees?

- If the private equity firm has multiple offices, how are these offices supposed to coordinate with each other in the event of a business disruption in either location?

Another key component of BCP/DR planning compliance departments now focus on is continued testing of said plans once implemented. While plan testing may be coordinated by departments other than compliance, such as a private equity GP's IT department, the compliance department is often instrumental in ensuring that plans are tested according to a predetermined schedule and that testing is documented appropriately. Key testing considerations that should be addressed by compliance in designing BCP/DR testing and oversight programs include:

- Is the plan tested? If so, how often?

- Are BCP/DR plans tested from a technology perspective solely or are personnel tests employed as well?

- When was the most recent test?

- What were the results of the test? Were any material issues noted? How have these issues been addressed?

7.5 SUMMARY

This chapter began with an overview of the increasingly important role played by information technology in implementing a successful compliance function in a private equity firm. We next discussed the reasons for the increased regulatory focused on the importance of a GP developing a robust compliance infrastructure. The discussion proceeded to a focus on the importance of cybersecurity in the modern private equity compliance risk management. The benefits of penetration testing and various methods by which it can be performed were examined. The risks posed to GPs and LPs through vendor cyber-vulnerabilities were also addressed. Common techniques utilized by hackers, including phishing, spear phishing, and domain spoofing, were introduced. The extensive use of data room by GPs in sharing information with LPs and underlying portfolio companies and among GP employees was also covered. Finally, the critical role of the compliance function in working with the information technology department and vendors in implementing the GP business continuity and disaster recovery program was analyzed. In this chapter we emphasized the importance of private equity compliance documentation related to information technology policies and procedures. In the next chapter we will expand this discussion to private equity compliance–related documentation outside of the information technology function.