CHAPTER 4

Valuation Compliance

4.1 INTRODUCTION TO PRIVATE EQUITY VALUATION

The majority of investments made by private equity funds are into the securities of underlying portfolio companies. In many instances these securities can be considered to have low levels of liquidity or be considered to be illiquid. As we outlined in Chapter 1, liquidity refers to how easy it is to execute a transaction in a particular investment (i.e. its purchase or sale). The result of these low liquidity and illiquid investments is that there are often not readily available prices for these securities. This often results in a situation where a private equity manager must actively pursue third parties (i.e. a broker or valuation consultant) to provide a price, or for the General Partner (GP) to determine the price of the position itself (i.e. manager marked securities).

In either case, the GP typically maintains a great deal of flexibility with regard to the specific valuation of assets held by the fund. Whenever a fund manager maintains such authority over their own funds, a number of inherent potential conflicts of interest are present. In order to provide oversight of these conflicts, there are a number of compliance policies and procedures that are commonly in place.

4.2 INTRODUCTION TO PRIVATE EQUITY VALUATION

The starting point for examining the valuation approach used in determining the value of the fund's holdings is rooted in the fund formation documents, namely the private placement memorandum (PPM) and limited partnership agreement (LPA).

An example of the valuation approach of the formation documents would typically outline that any assets with high or medium degrees of liquidity would be priced as follows:

- Securities that are listed or quoted on a recognized securities exchange shall be valued at the average closing sales price for that security on a trading day.

- A security that is traded over-the-counter shall be valued at the average closing sales price for that security on a trading day.

An example of the valuation methodology outlined in the formation documents for those assets that are not freely tradeable (i.e. low liquidity or illiquid) is outlined below:

The fair market value of all non-freely tradeable assets of the fund shall be based upon relevant factors as may be deemed so in the sole and absolute discretion of the GP, including:

- Sales prices of recent transactions in the same or similar securities

- Current financial position

- Liquidation terms or other special features of the security

- Operating results of the issuer

- Level of interest rates

- Other general market and economic conditions.

- Significant events that have affected or will influence the underlying portfolio company, including any pending private placement, public offering, merger, or acquisition

- The price paid by the fund in acquiring the asset

- The percentage of the issuer's outstanding securities that is owned by the fund

- All other factors affecting value in accordance with practices customarily employed by the industry

As this example shows, solely based on the formation documents alone the GP maintains significant discretion with regard to the valuation of these types of low liquidity and illiquid assets for which valuations are not readily available. GPs, however, cannot simply make an arbitrary valuation based on what they feel a particular asset may be worth. Instead, GPs often make these determinations through the use of what is known as a valuation committee.

4.3 GP VALUATION COMMITTEES

While often not a technical requirement, to provide additional support for any valuations reached by the GP it is considered best practice for a GP to create a valuation committee. This committee typically resides not at the fund level, but instead at the GP level and generally performs valuation work across all funds managed by the GP.

4.3.1 Valuation Committees Membership and Size

The members of the valuation committee typically consist of senior GP personnel, including fund portfolio managers, accounting, compliance, and operations professionals. There is also no prescribed specified size for valuation committees, and the number of members may vary depending on a number of factors, including the size of the private equity firm.

4.3.2 Valuation Committees' Meeting Frequency

Private equity fund valuation committees typically meet on a quarterly basis. They may also meet more frequently as needed to review any valuations issues that arise on an intra-quarter basis.

4.3.3 Valuation Committees' Duties

The primary goal of the valuation committee is to ensure the firm's valuation policies and procedures are being applied consistently across the funds. To be clear, the valuation committee members are not typically the ones calculating the actual values of fund holdings themselves, but are rather reviewing the valuations calculated by others. As part of this oversight, the committee will also typically review prior valuations, financial performance for each portfolio company, recent valuations for comparable companies, and valuation trends of public equity markets.

Due to the relatively small number of holdings in private equity fund portfolios, valuation committees may also have smaller subcommittees that specifically focus on the valuations of individual positions. The membership of these subcommittees may overlap with the primary valuation committee. The way these subcommittees typically work is that the investment deal team responsible for a particular portfolio company will meet with a valuation subcommittee to analyze any new developments at a particular portfolio company that have taken place since the most previous valuation. This information would then be used by the subcommittee in determining a valuation to recommend to the larger valuation committee to review. In many cases, the valuation committee would then review their final valuations with the GP's investment committee. In some cases, the investment committee, and not the valuation committee, may maintain final approval of valuations.

4.4 VALUATION POLICIES

In many cases, a private equity firm will develop stand-alone valuation policies that describe in more detail the day-to-day practices employed in valuing a fund's holdings. These can be distinguished from the more legally accurate but less practical valuation policy descriptions contained in the fund formation documents as referenced previously.

4.5 VALUATION FREQUENCY

When a position is first purchased a common convention is that it is marked on the books of the private equity fund as being held at cost (i.e. the price paid for the asset). This is fairly straightforward – the asset is worth as much as the fund paid for it. When the asset is eventually sold, the asset is then typically valued at the price that the fund sold the asset for (i.e. it was worth what someone else was willing to pay for it). These two points, the purchase and sale, can be referred to as transaction-based valuations. The more complicated situation is determining the value of an asset held by a fund throughout the life of the investment, when a transaction does not occur.

The frequency with which a GP conducts valuation between the time of its purchase and sale may vary. Commonly, a GP may decide to regularly revisit valuations on a predetermined frequency (i.e. quarterly). If they feel that an asset's value has changed, they would likely revalue it accordingly. In other cases, a GP may determine values outside of a predetermined time frame, such as if a material event occurs which they feel would impact the valuation. Regardless of whether a material event occurs or not, it is still considered best practice for a GP to revisit the valuations of the holdings of a fund with at least some predetermined frequency.

4.5.1 Valuation Memorandum and Support

When a GP seeks to value a position in a fund after it has been purchased there are effectively two possible outcomes. The first would be that the GP makes the determination that the value of the asset has not changed since the time of the last valuation (i.e. last quarter). The second option would be that the GP determines that a valuation change has occurred. In either scenario it would be considered best practice for the GP to produce a written summary of their valuation conclusion. This is known as a valuation memorandum. To be clear, even if no valuation change has occurred, it is still considered best practice for the GP to write a brief memo to this effect in order to memorialize this determination.

When a valuation change does occur in the asset (i.e. the GP determines that it has either increased or decreased in value), the valuation memorandum should include details of how the new valuation was determined, including:

- An executive summary outlining the new value and the change this represents from the previous value

- A description of the use and application of any models utilized in determining valuations

- Input data and support documentation used in calculating the value

- Recommendations with regard to any concerns that would result in increased monitoring of valuations and valuing the asset more frequently

Due to the often technical nature of the details of the valuation methodology that require extensive familiarity with a fund's holdings, members of the investment team would typically work to produce these valuations for presentation to valuation subcommittees or directly to the primary valuation committee as the case may be.

4.5.2 Use of Third-Party Valuation Consultants

In certain instances, a GP may engage the use of a third-party valuation consultant. These are service providers that will provide an independent valuation of a particular asset or group of assets. The use of these third parties is typically at the GP's discretion; however, in certain instances the fund formation documents may mandate that a third-party valuation consultant be engaged in the event a single asset breaches a particular threshold of a portfolio's total size (i.e. greater than 20% of committed capital).

In a private equity context, the use of valuation consultants continues to remain relatively limited as compared to other areas of the asset management industry, including the hedge fund space. The primary reason for this is the considerable expense involved in obtaining these third-party valuations. Additionally, the GP as the manager of the fund is considered to maintain a particular expertise with regard to the valuation of assets in their investment space. To further support this point, even if a fund does utilize a valuation consultant, in most instances it is not bound to accept the work of this consultant as binding; instead whether to use the valuation is in the discretion of the GP. If significant valuation concerns are raised by limited partners (LPs) regarding a GP's valuations, there are typically mechanisms in place by which a limited partner advisory committee (LPAC) or majority in interest LPs can challenge the valuation.

4.6 LPAC VALUATION OVERSIGHT

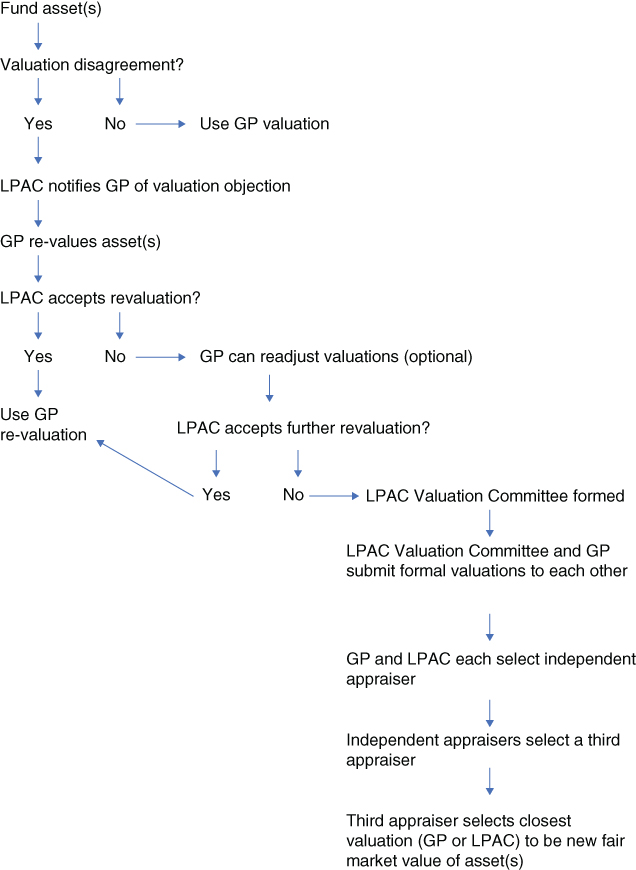

Private equity funds formation documents typically outline the valuation approach and standards that will be applied in valuing fund investments. The valuation of a fund's investments is critical to LPs as it is a key driver of their overall profitability. As part of this valuation process, LPACs play a critical role in representing LPs in voicing their opinions of the valuations determined by the GP. Fund terms will typically outline that the LPAC has the right to object to the GP's valuation of one or more assets. If they do object, then they may notify the GP of their objection within a pre-specified time period (i.e. within 30 days).

If the LPAC sends this notification to the GP within the required time frame, the fund terms will typically dictate that the GP then has to re-value the asset in question. If the LPAC still disagrees with this revaluation, then the GP may have another opportunity to adjust their valuations again. If no agreement can be made between the GP and LPAC as to the appropriate valuation, then the asset in question would be subjected to an appraisal procedure. These procedures may differ among funds; however, in general, within a specific time period (i.e. 21 days) the LPAC would then form a separate LPAC valuation committee. In practice the LPAC valuation committee could consist simply of the existing LPAC members or may also contain other LPs.

After the LPAC valuation committee has been formed, the committee and GP would then formally provide each other with the proposed value for the asset. As there would likely still be a disagreement in the two valuations at this point the next step would be for each party to select an independent appraiser. Each appraiser must be generally acceptable to the other party. Rather than have each appraiser value the security, these two independent appraisers then select a third appraiser. This third appraiser will then typically not directly value the security themselves, but rather select which proposed value, either the LPAC valuation committee's or the GP's, is closest to the actual fair market value of the asset(s) in question. Once this valuation has been selected, it becomes the new fair market value of the asset.

After the process is complete the LPAC valuation committee would then dissolve. It is also worth noting that throughout the process described earlier, if an agreement is made among the parties on the valuation, then the process would just stop at that point. A summary of this entire back-and-forth between the GP, LPAC, LPAC valuation committee, and appraisers is summarized in Exhibit 4.1.

Exhibit 4.1 LPAC Valuation Oversight Decision Tree Example

Due to the fact that this is a time-intensive, complicated, and expensive process, unless there is a substantial disagreement among the LPAC and GP with regard to the value of asset, a compromise will generally be reached; or instead the LPs will typically defer to the GP's expertise in valuing assets.

4.6.1 Third-Party Fund Administrators

As we introduced in Chapter 3, a fund administrator is a third party that performs two primary services – fund accounting and shareholder services. Within the fund accounting function, the types of services traditionally provided include:1

- Logging any new asset purchases and trades made by the private equity fund

- Calculation of profit and loss

- Calculation of fees and accruals

- Calculation of net asset value and preparation of financial statements

- Partnership accounting

- Financial accounting/general ledger maintenance

- Performance measurement

- Reporting for investment managers

- Preparation of interim financial reporting

The primary duties provided by the shareholder services function generally include:

- Overseeing the capital commitment and investor withdrawals process, which includes receiving and processing all the relevant documentation and complying with private equity specific criteria such as required redemption notice periods, lockups, and potential redemption penalties

- Ensuring compliance with the anti-money-laundering and know-your-client requirements in each jurisdiction

- Tax reporting for investors

The majority of private equity firms still follow a self-administration model, whereby the GP serves as its own administrator. This is in contrast to the hedge fund industry, which has embraced the third-party administration model. In some cases, certain larger hedge funds have moved to a model of utilizing two different third-party administrators to check each other's work. Due to the potential conflict of interest present in this relationship there has been increasing pressure in recent years by LPs to push GPs toward embracing a third-party administration model to provide enhanced independence and oversight over the fund processes described earlier.

Although private equity funds are still limited in their use of third-party administrators, the services offered by these administrators have continued to expand over time. One such service that has gained traction is known as asset verification. Under this process the administrator will reach out to a private equity fund's trading counterparties and custodians to independently confirm that the fund is indeed holding the assets that it claims to be holding. This is an example of a way in which fund administrators can provide additional oversight of a fund to LPs.

Typically, due to the highly specialized and illiquid nature of private equity investments the majority of third-party administrators will only be able to provide material valuation support services to any liquid holdings of a private equity fund's portfolio that may be present. This would be assets that are easily priced from third-party exchanges or pricing feeds. However, the bulk of a private equity fund's portfolio typically consists of low liquidity or illiquid assets and, therefore, the role of administrators in providing valuation support is relatively minimal.

4.7 CASE STUDIES IN VALUATION

Regulators have increasingly focused on the valuation compliance practices employed within the private equity industry. The following two cases demonstrate action taken in this area by the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). As you review these matters, keep in mind the inherent potential conflicts of interest present in the private equity valuation process and the compliance oversight measures that can be put in place to monitor these potential conflicts.

4.7.1 Case Study #1: JH Partners, LLC

JH Partners, LLC (“JHP”) was a Delaware limited liability company based in San Francisco, CA, that had been registered with the SEC as an investment adviser since March 2012. At the time of the SEC action in this matter, the Firm provided investment advice to three private equity funds, JH Investment Partners, LP, JH Investment Partners II, LP, and JH Evergreen Fund, LP. As of March 31, 2015, JHP's total assets under management were $465.4 million. The SEC Administrative Proceeding in this mater described the allegations of the case as follows:2

From at least 2006 to 2012, JHP and certain of its principals loaned approximately $62 million to the Funds' portfolio companies to provide interim financing for working capital or other urgent cash needs. By doing so, JHP and its principals in certain cases obtained interests in portfolio companies that were senior to the equity interests held by the Funds. JHP also caused more than one Fund to invest in the same portfolio company at differing priority levels and/or valuations, potentially favoring one Fund client over another.

JHP did not adequately disclose to the advisory boards of the affected Funds the potential conflicts of interest created by the undisclosed loans and cross-over investments. Finally, JHP failed to adequately disclose to, or obtain written consent from, its client Funds' advisory boards when certain of their investments exceeded concentration limits in the Funds' organizational documents. Accordingly, JHP violated Sections 206(2) and 206(4) of the Advisers Act and Rule 206(4)-8 thereunder.

JH Partners agreed to a cease-and-desist order and a $225,000 penalty as part of its agreement to settle the case.3

4.7.2 Case Study #2: Oppenheimer

The primary entities involved in this matter were:

- Oppenheimer Asset Management Inc. (“OAM”)

- Oppenheimer Alternative Investment Management, LLC (“OAIM”)

- Oppenheimer Global Resource Private Equity Fund I, LP (“OGR”) – a private equity vehicle

As background, at the time of the allegations in this case, the SEC Administrative Proceeding in this matter described that OAM was located in New York City and was registered with the Commission as a Registered Investment Adviser. OAM was a subsidiary of E.A. Viner International Co., which is a subsidiary of Oppenheimer Holdings, Inc., a publicly held company listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Furthermore, OAIM was wholly owned by OAM, and OAM is the sole member of OAIM. OAIM was the general partner of and, through employees of OAM, provided investment advisory services to several funds, including OGR and other private equity funds. Accordingly, OAM could have been deemed to have served as the investment adviser to OGR. The SEC Administrative Proceeding in this mater described the allegations of the case as follows:4

From October 2009 through 2010, Respondents disseminated marketing materials to prospective investors and quarterly reports to existing investors that contained material misrepresentations and omissions concerning Respondents' valuation policies and OGR's performance. Respondents stated in the marketing materials and quarterly reports to investors that OGR's asset values were “based on the underlying managers' estimated values” when that was not the case with respect to one of the assets in OGR's investment portfolio.

Beginning in October 2009, while OGR was being marketed to new investors, OGR's portfolio manager (“Portfolio Manager”) changed the value of OGR's largest holding, Cartesian Investors-A, LLC (“Cartesian”), using a different valuation method than that used by Cartesian's underlying manager. The Portfolio Manager did not inform, and caused Respondents not to inform, investors either of this change or of the fact that the new valuation method resulted in a significant increase in the value of Cartesian over that provided by Cartesian's underlying manager.

Additionally, former employees overseeing OAIM's investments misrepresented and caused Respondents to misrepresent to potential investors that:

- the increase in Cartesian's value was due to an increase in Cartesian's performance when, in fact, the increase was attributable to the Portfolio Manager's new valuation method;

- a third party valuation firm used by Cartesian's underlying manager wrote up the value of Cartesian when that was not true; and

- OGR's underlying funds were audited by independent, third party auditors when, in fact, Cartesian was unaudited.

Former employees overseeing OAIM's investments and the Respondents marketed OGR using the marked-up value of the Cartesian investment from October 2009 through June 2010 and succeeded in raising approximately $61 million in new investments in OGR during that period.

Oppenheimer agreed to pay more than $2.8 million to settle the SEC's charges and the Massachusetts Attorney General's office announced a related action and additional financial penalty against Oppenheimer.5

4.8 SUMMARY

This chapter examined various compliance aspects and procedures relating to the valuation of a private equity fund's holdings. We first examined the common language relating to private equity valuation guidance from a fund's formation documents. Next, we addressed the role played by valuation committees in overseeing valuations. This included a discussion of the size of these committees, their specific duties, and meeting frequency. The role of investment personnel in working with valuation committees, as well as the role of valuation subcommittees was also addressed. The production of valuation memorandums and the role of third-party valuation consultants and fund administrators were examined. LPAC valuation oversight and mechanisms for resolving valuation conflicts between the GP and LPs were analyzed. Finally, case studies regarding regulatory actions in the area of valuation oversight were presented. A key consideration in the valuation of private equity fund holdings related to the conflicts of interest inherent in this process. In the next chapter, we will address the subject of conflicts of interest in more detail as they relate not only to valuation, but to the larger private equity fund management process.