CHAPTER

7The Plan: Preproduction

The producer is like the conductor of an orchestra. Maybe he can't play every instrument, but he knows what every instrument should sound like.

Richard Zanuck

THIS CHAPTER'S TALKING POINTS

| I. | The Script |

| II. | The Talent |

| III. | The Crew |

| IV. | Scheduling the Shoot |

In the preproduction phase, hundreds of details come together to form the big picture, like pixels on a TV screen. These details are the essence of production. They add dimension and texture to your project. When you devote attention to these preproduction details—researching, double-checking, and making dozens of careful decisions—you can often save costly mistakes. Planning ahead is easier than going back and trying to cover your mistakes. You can find an in-depth preproduction checklist on the web site for this book that summarizes the many details that you'll need to be aware of as you plan your shoot.

I. THE SCRIPT

If you are shooting a narrative script, like a dramatic series or online short, you ideally want the script to be completely finished before you start shooting. The late delivery of shooting scripts can limit everyone's preparation time, and slow down the production itself. You do not want to realize as you're shooting that an essential story element is missing, requiring a last minute rewrite and stopping production, even though you're still paying everyone to wait. The more time you can give to your preproduction planning, the better your chances for a seamless shoot.

Maybe you've got a full script that can serve as a blueprint for your preproduction planning. Or perhaps your project is reality-based and you've only got an outline for who and what you hope to shoot. Yet in both cases, you'll carefully review each element before you begin shooting. Both extremes, and every kind of project in between, require preproduction strategies.

The Top Ten Things a Producer of Documentaries Should Know

1. There's no substitute for a good story.

2. Working with great people is better than working with a lot of money.

3. How to write.

4. How to use as much of your production gear as possible (just in case).

5. How to budget (and stay within it).

6. If you're traveling with equipment, show up really early at the airport.

7. If you're going on location somewhere, it's best to have someone local on the crew.

8. It's never going to be the way you expect it to be.

9. It's okay to ask for advice.

10. Everything takes longer than you think it will.

Michael Bonfiglio, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

Script Breakdowns

Chapter 4 explored the budget ramifications of your project by breaking the script down into specific categories. You can now apply this same breakdown process to preproduction planning.

A breakdown sheet is a valuable tool that helps you organize and categorize your production details—the crew, on-camera talent, locations and sets, props, wardrobe, stunts, explosives, and more. There's a sample breakdown sheet form on this book's web site that can help define each element in your script (or storyboards) that you'll need to shoot.

Each scene requires its own breakdown sheet, and includes any or all of the following components:

![]() The script's title and scene number

The script's title and scene number

![]() The date of the breakdown sheet

The date of the breakdown sheet

![]() The page number of the script

The page number of the script

![]() Location: A constructed set or a real location

Location: A constructed set or a real location

![]() Interior or exterior: Shooting inside or outside

Interior or exterior: Shooting inside or outside

![]() Day or night: This determines choices of equipment and gear

Day or night: This determines choices of equipment and gear

![]() Brief scene description

Brief scene description

![]() Cast with speaking parts

Cast with speaking parts

![]() Extras: Any nonspeaking people in the scene or background

Extras: Any nonspeaking people in the scene or background

![]() Special effects: From explosions to blood packs to extra lighting

Special effects: From explosions to blood packs to extra lighting

![]() Props: Anything handled on-camera by a character in the scene, like a telephone

Props: Anything handled on-camera by a character in the scene, like a telephone

![]() Set dressing or furnishings: On-camera items on set not handled by the character

Set dressing or furnishings: On-camera items on set not handled by the character

![]() Wardrobe: Any clothing pertinent to a scene, like an outfit or torn shirt

Wardrobe: Any clothing pertinent to a scene, like an outfit or torn shirt

![]() Makeup and hair: Normal makeup and sfx, such as wounds or aging, wigs or facial hair

Makeup and hair: Normal makeup and sfx, such as wounds or aging, wigs or facial hair

![]() Equipment: Audio and video equipment and extras, grip, electric, cables, etc.

Equipment: Audio and video equipment and extras, grip, electric, cables, etc.

![]() Special equipment: Jibs, cranes, a dolly, Steadicams

Special equipment: Jibs, cranes, a dolly, Steadicams

![]() Stunts: Falls, fights, explosions; may include a stunt coordinator

Stunts: Falls, fights, explosions; may include a stunt coordinator

![]() Vehicles: On-camera cars or other vehicles in the scene or as background

Vehicles: On-camera cars or other vehicles in the scene or as background

![]() Animals: Any animal that appears in the scene comes with a trainer, or wrangler, who takes charge of the animal during production

Animals: Any animal that appears in the scene comes with a trainer, or wrangler, who takes charge of the animal during production

![]() Sound effects and/or music: Anything played back on set, like a phone ringing, music for lip-syncing, or music the actor is reacting to

Sound effects and/or music: Anything played back on set, like a phone ringing, music for lip-syncing, or music the actor is reacting to

![]() Additional production notes

Additional production notes

Production Book

All productions involve details—hundreds of them. As you saw in Chapter 4, organizing these details is easier when the producer uses a production book. The traditional production book is kept in a three-ring loose-leaf binder, with dividers for each section. On a small project, the producer keeps her own book, and updates it regularly. On a larger production, usually a production assistant (PA) or production coordinator is put in charge of making multiple copies of production books for the key production personnel, giving everyone the same updated information. Refer back to Chapter 4 when compiling your own production book.

Equipment List

Each member of the crew either provides his or her own equipment as part of the contract at an extra rate, or gives an equipment request to the producer, prior to the shoot. Special production equipment needs to be arranged in advance of the shoot, and might include:

![]() Cameras and lens, screens, tripods, batteries, video stock, etc.

Cameras and lens, screens, tripods, batteries, video stock, etc.

![]() Sound, extra mics, mixers, booms, windscreens, lavs, wireless bodypaks, etc.

Sound, extra mics, mixers, booms, windscreens, lavs, wireless bodypaks, etc.

![]() Grip and electric with cables, extra power sources, generators, cords, gaffer's tape, etc.

Grip and electric with cables, extra power sources, generators, cords, gaffer's tape, etc.

![]() Walkie-talkies

Walkie-talkies

![]() A dolly and tracks

A dolly and tracks

![]() Additional cranes and jibs for cameras

Additional cranes and jibs for cameras

![]() Steadicam mounts

Steadicam mounts

![]() Explosive devices

Explosive devices

![]() HMI and other lights, gels, stands, and neutral density gels

HMI and other lights, gels, stands, and neutral density gels

![]() Camera cars

Camera cars

![]() A video monitor for each camera

A video monitor for each camera

![]() Teleprompters

Teleprompters

The Look and Sound of Your Project

After you have organized these components, you can begin to explore the more aesthetic dimensions of your project.

Your visual approach provides important clues to the viewer. A narrative drama can reflect a moody noir texture requiring sophisticated lighting and a single-camera film technique; sitcoms are brighter, use more color, and usually take the traditional three-camera approach. A reality show might depend on three or four hand-held cameras; an online show can be shot in close up with one video camera. Elements such as lighting, camera lenses and angles, video or film stock, wardrobe, makeup, props, and set design all contribute to the overall visual aesthetics.

Shooting original footage is not your only option. Producers of all programming genres make clever use of components such as stock footage, still photos, archival or historical footage, text, documents, or graphics in postproduction either to augment or replace original footage. These elements can also add visual and audio effects and textures to the overall look.

The audio impressions you create are no less important. Sound can create subtle, even subconscious effects; though an audience isn't always conscious of what they hear, they get an audio impression. The clarity of dialogue and the ambient background sounds such as birds, traffic, a voice on the radio, a humming freezer, background conversations, all adds nuance to the story. The many elements of sound can be designed and enhanced in postproduction. Sound design can contribute to your essential narrative beats, or it can be distracting if it's not done well. A professional sound designer is a real asset to your production.

Storyboarding and Floor Plans

The next step is to plan out how you're going to shoot each scene. A scene, for example, might call for one long shot, or it might require master shots, individual close-ups, pans, two-shots, and cutaways. These shots are planned to fit together later in the editing process. By the time you actually shoot each scene, you will have totally planned it out.

Depending on the producer and/or the size of the project, there are a couple of ways in which to plot out each step of the production.

Storyboards are sketches in numbered boxes that illustrate the details of the scene to be shot. They can be simple hand-drawn cartoon-like sketches, or elaborate pictures generated from storyboard software. Each drawing represents a scene or shot number from the script (see the storyboard form example on this book's web site). When the image or camera angle changes, so does the content of the box.

Before the actual shoot, the producer reviews the script, often with the director, UPM, and/or line producer. They storyboard each scene. They detail every camera setup in that scene. Does the camera go in this corner and shoot in that direction? Is it a close-up or a two-shot? Does the shot work in the overall edit sequence? Where are the actors placed? Do any set, prop or wardrobe details in the shot need special attention?

Most storyboards are minimal black-and-white line drawings, although they can be full-color illustrations, photographs, or even animation. They save time and money by providing a visual synopsis of the scenes to be shot, the look and the feel of the set or location, the location of one character to another and their actions, and even the colors, textures, and mood of a scene.

All these aspects are essential to an art director, production designer, director, producer, the director of photography (DP), and others involved in production. However, not all projects can be storyboarded; many reality-based shows are shot with little or no advance knowledge of the shooting circumstances. And in many television dramas on a tight schedule, the camera coverage can't be planned until the scene is blocked for the camera on the actual day of shooting.

IN THE TRENCHES…

Storyboards, if they're imaginative and descriptive, have proven to be great tools for selling an idea or project. I've often pitched project ideas with just a set of storyboards. They can be on strong boards or paper, or as a PowerPoint presentation. This way, the clients get a clever glimpse into what my project could look like, without my having to shoot a scene or a trailer for a lot more money.

![]()

Floor plans provide an overhead view of what you plan to shoot, as well as the space around it. In complex, highly detailed projects, a floor plan can augment or replace the storyboard. It shows where the cameras and microphones are placed, as well as the lights, the actors, furnishings, set walls, and more. A floor plan helps the various department heads see what's needed for that scene, like props, furnishings, and set design. Because a floor plan shows the camera placements and shooting angles, it helps the DP plan how to best block the actors. Floor plans and storyboards both illustrate the shoot and make it easier for everyone involved to visualize the project's vision.

Shot List

When the producer carefully studies the storyboards, she can then put together a shot list. This is a detailed list of each shot that's part of a scene or specific sequence. Most shot lists are made on set after a blocking rehearsal; when time allows, they're ideally put together prior to the day of the shoot. The shot list is distributed to the camera and audio crew, as well as to other crew members who are directly involved in the shoot.

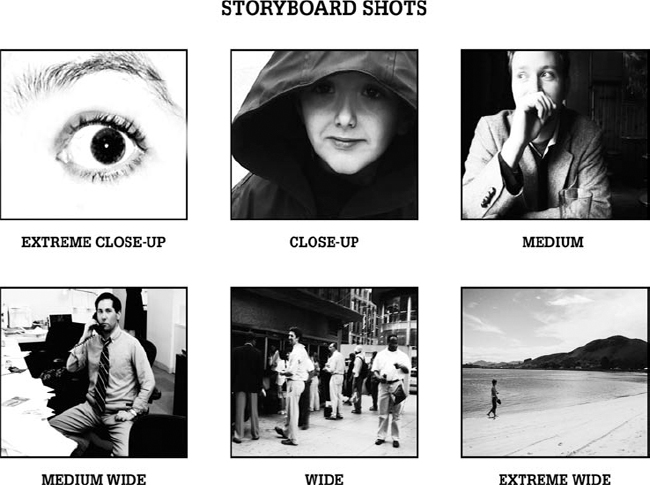

The shot list uses a specific language that everyone understands to describe the shot that is needed:

![]() ECU: Extreme close-up (eyes or mouth, or part of an object)

ECU: Extreme close-up (eyes or mouth, or part of an object)

![]() CU: Close-up (the whole face or entire object)

CU: Close-up (the whole face or entire object)

![]() MS: Medium shot (an upper torso or an object in part of its surroundings)

MS: Medium shot (an upper torso or an object in part of its surroundings)

![]() MWS: Medium wide shot (most or all of a body or group of objects) that's framed between a medium shot and wide shot

MWS: Medium wide shot (most or all of a body or group of objects) that's framed between a medium shot and wide shot

![]() WS: Wide shot (an entire body or larger grouping of objects)

WS: Wide shot (an entire body or larger grouping of objects)

![]() EWS: Extreme wide shot (many bodies or shots of horizons, buildings, sky lines, etc.)

EWS: Extreme wide shot (many bodies or shots of horizons, buildings, sky lines, etc.)

Production Meetings

No matter where your project will eventually end up—on a major network, online, on a mobile phone, in a short film festival—your team is a vital part of making it all come together. You want to encourage good communication and collaboration during the production; one approach is to schedule daily or weekly production meetings.

Production meetings generally include the key people like the producer(s), director, line producer, production manager, and whoever else you want to be involved. Prior to the meeting, you'll create an agenda and make copies of documents or plans to be discussed, including the script or shooting schedule or myriad other details. Two areas stand out as particularly important, regardless of the size of your production.

![]() The production meeting is called by the producer, and invites any key positions (the gaffer, key grip, DP, sound mixer, production designer, wardrobe, AD, etc.), even if your production is a small one. Go through the schedule together, step by step, and discuss.

The production meeting is called by the producer, and invites any key positions (the gaffer, key grip, DP, sound mixer, production designer, wardrobe, AD, etc.), even if your production is a small one. Go through the schedule together, step by step, and discuss.

![]() If your project is scripted, or benefits from rehearsal time, do a read-through of the script with the cast and crew.

If your project is scripted, or benefits from rehearsal time, do a read-through of the script with the cast and crew.

Everyone's encouraged to give notes or comments, while you listen, set priorities, delegate jobs, and generally take care of business. After the meeting, send out a memo and outline what was said and agreed upon. Production meetings can be an excellent forum for complimenting those people who are doing their job well in front of everyone else. If, on the other hand, you have a problem with a specific person, the production meeting is not the place for discussion. Do that later, in private.

I love bringing talented people together. There's no greater feeling than standing on a shoot, sitting in an edit session, or watching the final product on TV, knowing that you as the producer pulled together an incredible, hard-working group of people to create it.

Justin Wilkes, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

II. THE TALENT

The word talent covers quite a range. Talent can apply to a world-famous actor, an on-camera news anchor, a game show host. Or, talent can mean real-life subjects in a documentary who have never been on camera before, the man on the street, children, animals, and extras.

Regardless of the genre you're producing, it's virtually impossible to have a project without on-camera talent; he or she is the backbone of your story who can give your project credibility and energy, and provide connection with a viewer.

Casting Talent

Finding on-camera talent—who are talented—can be a full-time job, especially when your project is especially dependent on acting talent, or a clever talk show host, or a gifted professional for a how-to show, or real people with a compelling story. Here are the steps that a producer can take to find just the right person.

Casting Directors and Agencies

Specialized talent agencies and casting directors work with producers and directors to help them find the right face, voice, or special skill for a project. Some casting professionals work only with actors, others specialize in casting “real people” or extras for a crowd scene or atmosphere.

Casting directors keep files on their clients: the actors’ resumes and headshots, possibly a reel with examples of their work, and make sure they're regularly updated. Casting directors are familiar with their clients’ skills, what other roles they've played, and their work ethic. A good casting director maintains solid relationships with talent agents, other casting directors, and talent managers, and can often help in negotiating overall talent fees and work conditions.

The producer first contacts the casting director and outlines the project's needs. Then the casting director calls agents, places ads, and/or posts notices for a casting call. Audition space is rented and times set up. Auditions are held in a rehearsal or casting space; the producer may shoot video and/or stills and reviews them later when he's making final casting decisions.

Guerilla Casting

You may not have a casting director at your disposal or the money to hire one. For low-budget projects, you can post your own notices and hold casting auditions in spaces that are inexpensive or free. So how and where can you find good talent?

![]() Write a short description of the part(s) you're casting, the audition date, time, and location, and a phone number or email address to get more information.

Write a short description of the part(s) you're casting, the audition date, time, and location, and a phone number or email address to get more information.

![]() Advertise your casting call in local newspapers and community penny savers.

Advertise your casting call in local newspapers and community penny savers.

![]() Many towns and cities have web sites with cultural links. Surf these sites for possible venues to post your audition notice or to find talent.

Many towns and cities have web sites with cultural links. Surf these sites for possible venues to post your audition notice or to find talent.

![]() Attend local theaters, high school and college plays, churches or synagogues, or youth groups that put on plays. Look for talented actors who stand out. Ask for permission to post a notice on their bulletin boards.

Attend local theaters, high school and college plays, churches or synagogues, or youth groups that put on plays. Look for talented actors who stand out. Ask for permission to post a notice on their bulletin boards.

![]() Post an audition notice in local film, television, and new media schools.

Post an audition notice in local film, television, and new media schools.

![]() If you want “real people,” your local grocery stores, health clubs, block associations, PTAs, or hardware stores might have a bulletin board for posting your audition notice.

If you want “real people,” your local grocery stores, health clubs, block associations, PTAs, or hardware stores might have a bulletin board for posting your audition notice.

![]() Consult with other producers and directors who work regularly with talent.

Consult with other producers and directors who work regularly with talent.

Casting Calls and Auditions

You've posted the casting notice. Now, you can begin to cast the parts. Because auditions tend to attract a lot of people, you want a system that helps you to keep track of who shows up, how well they read the part, and how to locate them. In an audition, you and/or your casting director will:

![]() Find a comfortable space for auditions. The room should easily accommodate you, possibly a director, assistant producers, and the talent. Check the room temperature, the acoustics, the amount of light, and its overall comfort factor. If needed, set up extra lighting. Supply water and enough chairs. Assign someone other than the producer or director to read any additional parts with the actor. You also want an ample waiting area outside the audition room. Assign a “people person” to the waiting area to keep the talent relaxed. Provide water and snacks.

Find a comfortable space for auditions. The room should easily accommodate you, possibly a director, assistant producers, and the talent. Check the room temperature, the acoustics, the amount of light, and its overall comfort factor. If needed, set up extra lighting. Supply water and enough chairs. Assign someone other than the producer or director to read any additional parts with the actor. You also want an ample waiting area outside the audition room. Assign a “people person” to the waiting area to keep the talent relaxed. Provide water and snacks.

![]() Schedule the audition. It helps if you time the reading yourself—read the part(s) and see how long it takes to read it a couple times, then add five to 10 minutes for conversation before and after. Consolidate the auditions by scheduling each actor for a specific time. Build flexibility into your plan; working actors often have several auditions a day, and some readings go longer than others.

Schedule the audition. It helps if you time the reading yourself—read the part(s) and see how long it takes to read it a couple times, then add five to 10 minutes for conversation before and after. Consolidate the auditions by scheduling each actor for a specific time. Build flexibility into your plan; working actors often have several auditions a day, and some readings go longer than others.

![]() Keep a log of those auditioning. List their name, agent (if any), phone number, email address, and the part they're auditioning for. Keep track of the talents’ photographs (headshots) and their resumes.

Keep a log of those auditioning. List their name, agent (if any), phone number, email address, and the part they're auditioning for. Keep track of the talents’ photographs (headshots) and their resumes.

![]() Make the script available. While they're waiting to read, give actors the pages from the script that they'll be reading (also called sides). This gives them time to get comfortable with the audition material. Or ask them in advance to prepare a monologue for the audition.

Make the script available. While they're waiting to read, give actors the pages from the script that they'll be reading (also called sides). This gives them time to get comfortable with the audition material. Or ask them in advance to prepare a monologue for the audition.

![]() Videotape the audition. A taped audition gives you a chance to review an actor's performance later, and to compare it with other actors’ performances. Take close-ups of facial expressions and wide shots for the overall performance and body language. After each actor leaves, make notes and label each headshot and tape to avoid confusion.

Videotape the audition. A taped audition gives you a chance to review an actor's performance later, and to compare it with other actors’ performances. Take close-ups of facial expressions and wide shots for the overall performance and body language. After each actor leaves, make notes and label each headshot and tape to avoid confusion.

![]() Be patient with children. They can be a casting challenge, regardless of their age or professional experience. Children get tired, hungry, grumpy, and nervous. Keep the environment calm and provide games, crayons, and books. Assign at least one PA to keep the kids occupied and the parents calm.

Be patient with children. They can be a casting challenge, regardless of their age or professional experience. Children get tired, hungry, grumpy, and nervous. Keep the environment calm and provide games, crayons, and books. Assign at least one PA to keep the kids occupied and the parents calm.

![]() Arrange for callbacks. After the auditions, you've hopefully found actors or talent who you want to see again for a second reading; these repeat auditions are known as callbacks. It's not unusual to call an actor back two or three times. The general rule, especially if the actor is a member of SAG, is to pay the actor a fee after three callbacks. When you've narrowed your choices down, audition potential cast members together for a reading. The chemistry between actors can make or break a project.

Arrange for callbacks. After the auditions, you've hopefully found actors or talent who you want to see again for a second reading; these repeat auditions are known as callbacks. It's not unusual to call an actor back two or three times. The general rule, especially if the actor is a member of SAG, is to pay the actor a fee after three callbacks. When you've narrowed your choices down, audition potential cast members together for a reading. The chemistry between actors can make or break a project.

![]() Actors deserve respect. Any talent you have rejected are worthy of a polite phone call or personal email. They may not have been right for this project, but could be perfect for another one in the future.

Actors deserve respect. Any talent you have rejected are worthy of a polite phone call or personal email. They may not have been right for this project, but could be perfect for another one in the future.

IN THE TRENCHES…

Auditions can be rushed and nervous-making. Stay focused. It's a real challenge to keep auditions from being repetitive for those of us who hold them. Few actors are comfortable in auditions, so help them out. Introduce them to key people in the room, and make eye contact, make a joke. You'll encourage a much better performance when you treat the talent with respect.

![]()

Hiring Talent: Union or Non-Union?

The category that covers “talent” is a broad one. It includes actors with major and minor parts, on-camera hosts, narrators, background extras, children, animals, magicians, stunt people, jugglers, nonprofessionals and “real people.”

Many are members of a talent union, though not all good actors are members of a union, and not all union members are good actors. But most experienced and professional actors belong to unions such as SAG, AFTRA, and Actors Equity for theatre, that impose specific rules under which the actors work. The producer must honor them or risk hefty fines from the union.

A low budget can limit producers, often requiring them to work with non-union talent, thus avoiding the additional salaries, expenses, paperwork, residuals, pension and welfare, and other regulated working conditions that talent unions require.

On the other hand, an independent producer, production company, network, or studio may take the steps necessary to become a union signatory, meaning they've agreed to comply with the guidelines and regulations of the union. And because a well-known actor can be the biggest selling point for your project, it's often worth becoming a union signatory and paying the actor's much-higher fees in exchange for the benefits you'll see at the box-office.

Becoming a union signatory involves taking a realistic view of its impact on your budget. There must be enough money to cover union talents’ wages as well as fringe benefits (payments that include payroll taxes, pension, health, and other union and/or employee benefits). Each union's web site provides the most current and up-to-date information on these costs.

Each talent union has its own guidelines, but most will work with you. Some may make special concessions for student productions, low-budget shows, and affirmative action contracts, as well as multimedia, new media, some educational projects, and Internet projects. The agreements generally include lowering the pay scales and allowing more flexibility in the overall working conditions. You can find in-depth information on this complex aspect of production in the Books and References section in this book's web site as well as by going to the web site of the specific union.

Union Actors

Talent unions such as SAG and AFTRA have listed their guidelines, pay scales, and other regulations on their web sites, along with the producer's role in honoring these requirements. Most producers work closely with the unions and can negotiate the requirements which usually include:

![]() Rate of pay. Daily, weekly, or per-picture rates.

Rate of pay. Daily, weekly, or per-picture rates.

![]() Per diem. When on location and away from home, a daily allowance to cover meals, transportation, and other production-related expenses.

Per diem. When on location and away from home, a daily allowance to cover meals, transportation, and other production-related expenses.

![]() Speaking lines. All on-camera parts with or without lines have their own pay scale. Additional recording and rerecording time may also be required at a later date.

Speaking lines. All on-camera parts with or without lines have their own pay scale. Additional recording and rerecording time may also be required at a later date.

![]() Screen credit. The actor's credit itself, its placement on the screen, the order of the name's appearance among other actors, and other union or contractual agreements.

Screen credit. The actor's credit itself, its placement on the screen, the order of the name's appearance among other actors, and other union or contractual agreements.

![]() Turnaround time. Usually a 12-hour break of time between the end of one shooting day and the call time for the next day. Check the union's web site.

Turnaround time. Usually a 12-hour break of time between the end of one shooting day and the call time for the next day. Check the union's web site.

![]() Meals and breaks. Talent must have regularly scheduled breaks to eat and to relax.

Meals and breaks. Talent must have regularly scheduled breaks to eat and to relax.

![]() Wardrobe stipends. A fee paid to actors who provide their own wardrobe.

Wardrobe stipends. A fee paid to actors who provide their own wardrobe.

![]() Specific requirements. Child actors work fewer hours than adults, and if they are absent from school, require a tutor, parent, or social worker to be with them at all times.

Specific requirements. Child actors work fewer hours than adults, and if they are absent from school, require a tutor, parent, or social worker to be with them at all times.

![]() Benefits. Additional monies paid to an actor for things like P&W (pension and welfare) and worker's compensation.

Benefits. Additional monies paid to an actor for things like P&W (pension and welfare) and worker's compensation.

![]() Travel. There are specific guidelines detailing an actor's flying status, such as first class only, or no red-eye flights.

Travel. There are specific guidelines detailing an actor's flying status, such as first class only, or no red-eye flights.

Often, there may be a SAG representative on the set. He or she is employed by the union to resolve any contract disputes or member complaints, and deals primarily with the producer on a day-to-day basis in this regard. In some cases, you can work with the talent unions for waivers on wardrobe requirements, turn around time, stipends, benefits, and other areas.

Non-Union Actors

Actors who are not members of an actors’ union deserve the same respect and base salary, whenever possible, as those actors who are protected by their unions. Producers are not required to pay them union benefits, and there are fewer restrictions for on-set hours or turnaround time. Producers do have an ethical responsibility to treat everyone fairly, regardless of their union status.

Real People

The popularity of reality-based programming, and the comparatively low costs of these shows, has increased the demand for talent who are “real people”—couples, singles, old and young. Most have never appeared on-camera and are therefore not union members. In such cases, it's up to the producer to play fair, go over all deal memos and contracts with the talent involved, and avoid any complications or potential claims later on.

Stunt Actors

Some actors do their own stunts, but most use a stunt double for dangerous action like a fall from a building or a fist fight. If a stunt is dangerous or complicated, a stunt coordinator is hired to plan and oversee the stunt actor's work. Most experienced stunt performers belong to stunt associations covered by SAG.

Extras and Background

Most programs feature people milling in the background, walking on a street, getting into buses, driving cars, eating at other tables in a restaurant scene. These extras add a layer of dimension and credibility to a shot. Depending on the scene, extras can be professionals in SAG, or are hired by casting agencies or nonprofessional locals—even friends and family can fill in as background. Extras are scheduled and rehearsed just like actors with larger parts.

Actors’ Staff

An actor might bring his or her own people into a production. In certain situations, the production pays these salaries and provides accommodations and workspace. These extra personnel might include:

![]() Hair and/or makeup. Knows the cosmetic (and emotional) needs of the actor.

Hair and/or makeup. Knows the cosmetic (and emotional) needs of the actor.

![]() Wardrobe designer or stylist. Maintains the talent's specific wardrobe “look,” keeps track of clothing, and mends and cleans the clothing needed.

Wardrobe designer or stylist. Maintains the talent's specific wardrobe “look,” keeps track of clothing, and mends and cleans the clothing needed.

![]() Wrangler. Has expertise in training or managing talent, and might be a wrangler for an animal or a child actor.

Wrangler. Has expertise in training or managing talent, and might be a wrangler for an animal or a child actor.

![]() Personal trainer. Often a necessity when the part calls for an actor's overall health, sex appeal, or specific physical demands of a part.

Personal trainer. Often a necessity when the part calls for an actor's overall health, sex appeal, or specific physical demands of a part.

![]() Secretary or personal assistant. Handles requests for personal appearances, correspondence, and phone calls, as well as production-related details.

Secretary or personal assistant. Handles requests for personal appearances, correspondence, and phone calls, as well as production-related details.

Rehearsals

Rehearsals can be viewed as a costly luxury in some budgets, but whenever possible, the producer looks for ways to afford rehearsal time. This valuable time not only gives actors an opportunity to fine-tune their part, but it also serves the director, director of photography, audio engineers, and lighting director in blocking, or planning, their shoot. This saves valuable time on set when the shoot begins.

Rehearsing Scripted and Narrative Content

In actor-driven projects, rehearsal time gives the talent an extra advantage. Actors can get more comfortable with the script, the camera blocking, and fellow actors’ individual styles and rhythms.

Depending on the project, the producer either hires a director who works directly with the talent, or rehearses and/or directs the actors himself. Not all projects require or have time for rehearsals before shooting, and not all actors want to rehearse; each has his or her own approach.

In most narrative dramas, commercials, or sitcoms, some directors give actors the freedom to interpret their roles; others prefer to “direct” the actors. Directors know what they want in a performance, and it is their job to motivate actors to explore their character's back story, create a specific regional accent, or use distinctive body language to explore the range of their roles.

Rehearsing Unscripted and Reality-Based Content

Whenever possible, documentaries, reality-based shows, talk shows, and sports and live events can often benefit from a technical rehearsal. For example, in planning to shoot a documentary, a producer might go to a location prior to shooting and rehearse her camera positions and moves, and decide where the microphones should be placed in relation to the talent.

Many nonscripted shows depend on special sets such as Tribal Council on Survivor, or on The X Factor and American Idol. The producer employs his “dream team” to run through all the possible challenges they might encounter during the actual shoot. And in most talk shows, producers often rehearse with stand-ins, or run through special demonstration segments, musical performances, fashion shows, and the like. Before the show begins taping, the producer does “look-sees” of every component of the show: “host entrance,” “guest entrance,” “desk cross,” and other aspects of blocking and rehearsing.

Blocking

Once the action of the actor or “real person” has been determined, the next step is blocking the scene. Blocking looks at the camera's placement in relation to the actors (or their stand-ins) and their sequences of steps and actions: it's like choreographing a shot and involves the DP, director, camera operator, the lighting director (LD) and lighting crew, the audio engineer, and usually the producer.

Blocking considers furniture, props, or greenery in the scene, the relationship between one actor and another, and how the camera can capture it all. Blocking decides what the camera is shooting and from what angle, and spots for cameras and actors—called marks—are usually marked with masking tape on the floor or wall as reminders.

III. THE CREW

Although the actors may reflect charisma on-screen, it's the crew who creates the real magic behind the scenes. Your project may require only a small two-person crew, or you might need several camera and audio operators, as well as lighting designers, DPs, set designers, and wardrobe and makeup specialists.

Hiring a full crew can be challenging to both novice and seasoned producers alike. You may have had some experience working on productions where you met professionals whose work you liked. If not, look for creative options. Ask other producers or filmmakers for their recommendations. Contact local production crews or national crew-booking companies (check this book's companion web site) and ask for crew reels to screen; these reels reveal a visual or aural approach that could be similar to your vision. Research television, new media, and film departments in universities that may have talented students who are eager for an opportunity to augment their experience, and may work for lower fees, even academic credit.

The essential point is that you have to try to gain the trust and the confidence of the client, and all the other parties—from all the audio people, from the staging people, the artist, all the parties involved in this event. You have to gain their trust, that you understand what their issues are, and bring them on board to be on the same team for the overall good of the project.

Stephen Reed, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

Regardless of the size of your crew, each crew member has his or her own area of specialty. Over time, you'll build your team of experienced, talented, and collaborative crew members who can be trusted and who share your vision. They are, quite simply, your lifeline.

The Key Production Department Heads

Whether your project is large and ambitious, or small and controlled, union or nonunion—certain areas in every production need at least one person to cover them. In lower-budget projects, one person may cover several of these areas. The key people the producer hires for almost every project are:

![]() The director

The director

![]() The director of photography

The director of photography

![]() The production manager

The production manager

![]() The assistant director

The assistant director

![]() The production audio engineer

The production audio engineer

![]() The production designer

The production designer

![]() The postproduction supervisor

The postproduction supervisor

Director

As discussed in other chapters, television—and now, new media—is the producer's domain. So, the producer can also be the director, or hires the director, or maps out the desired look and creative approaches of the production.

If a director is hired, she may fill the traditional film director's role, working with actors, the crew, and the producer in visualizing scenes. The director can be a strong creative force in the production, supervising the writing, the casting, rehearsing the actors, and crafting the overall aesthetic approach.

Or, the director might be the technical director (TD) who, in a studio setting, works out of the control room. She is generally assigned to multicamera shoots, such as talk shows and live events, and among other responsibilities, directs each camera and “calls the shots” as they come into the control room, often creating a line-cut, or rough edit, in the process.

Under the Directors Guild of America (DGA) guidelines, the director, the AD (see later), and the technical director fall into a separate fee category and pay scale. Although each project is unique, it thrives when the producer and director cohesively and collaboratively work together.

Director of Photography

The DP is often the first key position to be filled. The DP brings the creative vision of the producer and/or director to life. Whether he actually operates the camera himself, or supervises the camera operator(s), he's mastered the essentials of lighting, formats of video and film, and the use of cranes and dollies. He can bring his own experienced people into the production, and helps outline a shooting schedule. The DP often owns his own equipment or has relationships with equipment rental companies.

Production Manager

The role of the production manager (PM) or unit production manager (UPM) varies in each project, depending on its size and budget. Hired by the producer, the UPM might be in charge of breaking down the script, and creating a schedule and budget from that breakdown. She keeps track of costs and deals with paying the vendors. She might also negotiate with and hire crew members, supervise the production assistants, arrange for equipment, and cover a range of essential details. Depending on the project, she monitors the daily cash flow; makes the arrangements for travel, housing, and meals; applies for shooting permits; oversees releases and clearances; and generally supervises the production activity. In a smaller or low-budget project, the producer or assistant producer doubles as the production manager.

Assistant Director

The assistant director (AD) is the on-set liaison between the director, the producer and/ or production manager, the crew, and the actors. He typically plays “bad cop” to the director/producer's “good cop,” helps to create the shooting schedule, and keeps the crew in sync with the day's schedule. The AD might also be responsible for timing shows or segments during taping. If there are scenes in which extras appear, he is often in charge of directing their actions.

Production Audio Engineer

The subtleties of sound design can get lost in preproduction planning, so a savvy producer hires an audio engineer who can capture the clarity of dialogue, background sounds, special on-location audio (sirens, birds, traffic, muted conversations), and other ambient audio. She knows how to place and monitor microphones (mics) like booms, wireless, small clip-on microphones (lavs), and windscreens for minimizing wind, air conditioners, fluorescent lights, and other sounds that can cause interference. She either owns her audio equipment or can lease what's needed for the project.

Production Designer

The aesthetic texture, design, the mood and tone are essential elements in every project. From creating elaborate sets, to simply rearranging set furniture, the production designer creates a design for the overall look of the show, and works closely with the producer and director to create an environment for the action. By finding out what camera shots and angles are planned, he designs what will be seen in the camera's framing. As always, the budget has an impact on these choices, although a clever production designer can improvise and plan carefully. He may do all the jobs himself. Or, he may hire an art director whose job it is to take charge of building and painting the sets, and/or to modify existing locations. Often, a set decorator is also needed to locate items for the set such as furniture, lamps, wallpaper, and rugs. The production designer and/or the art director also decide on carpenters, greens specialists, prop masters, painters, and other support crew.

Postproduction Supervisor

Whenever possible, a producer hires a postproduction supervisor. Her overall responsibility is to be well-prepared for the postproduction stage, consulting with the producer in making early decisions about postproduction details—the choice of editor and the editing facility and the software program that's best for the project; the sound designer and the audio mix facility; the graphics designer and facility; and other postproduction elements.

In some productions, the postproduction supervisor comes on board during production and sets up systems for screening the dailies, and organizes, labels, and stores the footage and audio elements. She understands the professional standards for editing, including nonlinear editing (NLE) systems as well as online systems and when they can come in handy. She's aware of the many video, audio, and graphics needs, and can coordinate them all together. More postproduction information can be found in Chapter 9.

Key Players, Key Teams: The Script, and the Visual, Aural, and Support Teams

Depending on the size of the production, most if not all of the following positions are hired in the preproduction phase.

The Writing Team

Writers and revisions. During the writing process, the original script writer(s) might be teamed up with new writers, replaced because of “creative differences” with the producer or writer, or leave the project because of prior commitments. The initial concept of the project can change as part of the creative process, or the client or network makes demands the writer isn't willing to make. Script revisions are generally agreed on in the writer's contract, either following WGA guidelines or on a fee-per-revision basis.

Researcher. Most projects require some degree of research. An historical storyline, for example, involves details in architecture, costume, or speech mannerisms. A reality-based show hires a researcher to look for background material, find interesting ideas and real-life characters. A quiz show depends on researchers to investigate subject areas for questions and correct answers.

Researchers are valuable components in news or fact-based programs for double-checking sources or backgrounds. They might be professionals, academics, or consultants who specialize in specific areas of knowledge, or who are adept at problem solving. Researchers can also be production assistants or other administrative staff who are assigned to specific research needs.

The Visual Team

Storyboard artist. Working with the producer or director, and examining each scene of the script, the storyboard artist translates the visuals onto paper, either by hand or using a storyboarding software program. These sketches are generally simple and cartoon-like, and show at a glance what needs to be created by the production team.

Lighting director. The LD works with, or doubles as, the DP. In some cases, the LD is known as the key gaffer or chief lighting technician. He designs the lighting for the production, plans where the equipment is best placed, and decides the best lights to use and their wattage. On set, the LD supervises the rigging of the pipes and the hanging of lights, and also recommends scrims, gels, and patches for various lights.

Camera operator. Either working with the DP or as the DP, the camera operator shoots the scenes, works with blocking and framing, lighting, and lenses for each shot. She also works closely with the audio engineer to make sure that the best audio goes into the camera and onto the video tape or into digital storage.

Assistant camera operator (AC). The AC helps the camera operator, keeps camera batteries charged and available, changes and maintains lenses, and sets up and breaks down the camera equipment. The AC also slates each take, works closely with the script supervisor, is in charge of keeping track of tape/film stock, and completes the camera reports for the editor. Some duties may be given to the second AC if one is hired.

Still photographer. The photographer takes a number of still shots during rehearsal and behind the scenes, as well as on set, for purposes of providing publicity stills as well as creating a photographic archive of the production.

Gaffer. This lighting specialist works closely with the DP and cameras to set up lights, adjust them during the shoots, supervise and install various gels and gobos, and supervise the electric power sources or generators.

Best boy. An assistant to the gaffer, the best boy (often a female) works specifically with electrical cables and ties them in safely to a power source or generator.

Key grip. This main grip works with the physical aspects of setting up the shoot, which includes rigging light stands and C-stands that hold up silks or cycs (hanging background fabric or paper) and installing special equipment such as a dolly and dolly tracks, camera jibs and cranes, and more. The key grip is also primarily responsible for overseeing safety procedures on set, especially in the presence of stunts and pyrotechnics, and supervises the crew of grips.

Grip. A grip's responsibilities include pushing the dolly, operating cranes or camera cars, helping with other equipment needs, and setting up, adjusting, and taking down lights.

The Audio Team

Boom operator. In the audio department, the boom operator works very closely with the camera operator and aims the boom (a long flexible pole with a microphone fixed to the end) at the audio source without getting into the camera's frame. Each camera has its own mic and boom operator. A boom can also be a large wheeled stand with a moveable arm from which the mic hangs.

Audio mixer. There are often several sources of audio in production. The audio mixer operates the console and separates each source onto a separate audio channel for postproduction mixing. The mixer might also “live mix” the sound as it comes into the console; this can make the postproduction audio mix easier or, in some cases, unnecessary.

Audio assistant. This member of the audio team keeps track of all audio equipment, changes and labels audio tapes, separates the microphone and audio cables from electrical cables, places mics on set or on talent, and often tapes the cables down either to hide them from the camera or to prevent people from tripping over them.

The Production and Administrative Team

Production secretary. As the liaison between the cast, the crew, the producer, and the UPM, the production secretary is often in charge of distributing paperwork such as call sheets, contacts sheets, schedules, paychecks, and other duties assigned per project. On smaller projects, the production secretary can also double as receptionist, PA, even handling the catering.

Script supervisor. A vital asset to the director, the script supervisor checks that all the planned shots in the script have either been shot or deleted. She is the watch dog for continuity. For example, when an actor wears a red tie in one shot, he needs to be wearing the same red tie in another shot that follows it in the script. Taking continual notes during the shoot, the script supervisor describes each shot in each scene and keeps notes on all takes. She notes gestures or movements (like a hand on someone's shoulder) that need to match another shot. She looks for matching dialects and dialogue, details in wardrobe, hair, and makeup (like matching a bleeding wound from one shot to another), and what lens is used. The script notes also provide important references and directions for the editor to use later in postproduction.

Location manager. The location manager looks for and secures locations for the production, negotiates the location agreements and rates, takes care of shooting permits, parking, on-location catering, and makes sure the location is in good condition after the shoot has wrapped. He's the liaison between the location and the producer.

Catering manager. She is in charge of providing water, coffee, tea, and snacks at all times, as well as arranging for a healthy hot meal at least every six hours. The catering manager sets up a table, cart, or vehicle for serving food as close to the production action as possible. This area is often split up between catering (meals) and craft services (or crafty) of drinks and snacks.

Transportation manager. The transportation manager (or a key driver called the transportation captain) is in charge of moving the cast, crew, and equipment from one location to another. The production may require the transportation manager to rent the proper vehicles such as mobile dressing rooms, honey wagons (portable bathrooms), trucks, or vans for equipment as well as keeping them operational and ready to move. This is a union position, strictly available to the Teamsters.

2nd assistant director (2nd AD). This crew member, when needed, assembles the call sheets, sets the call times for the cast and crew, and tells the cast and crew where to show up and at what time. She may also direct any action in the background involving extras.

2nd-2nd AD. If a situation calls for traffic or crowd control, he may be in charge. He also secures the set in whatever ways are necessary and works with the production secretary to coordinate the actors for their arrival on set.

Production assistant (PA). A necessity in all departments, the PA can be a tremendous asset who contributes both physical labor and administrative help. Most productions have a pool of PAs, assigning them on set, in the office, on location, or wherever help is needed. PAs are on set first, and they leave last. They're available to help in all departments, to do whatever needs doing. Most location PAs must be able to drive, often large equipment trucks, understand local parking restrictions, and be trusted to guard expensive equipment. Office PAs keep track of budgets, copy and distribute the latest script revisions, help with auditions, take care of talent needs, and often go back and forth between the set/location and the main office.

Interns. Often college or high school students can work for a semester on a production for school credit, while learning in the process. Few interns have worked in television production before; they require an intern supervisor to make sure they're doing their assigned tasks and are also getting a positive and organized learning experience. Interns are paying for their internships in school credits, and their energy is important to the production. Like PAs, they're assigned to areas where help is most needed.

The Top Ten Most Important Tools for PAs and Interns

1. Mobile phone. Use it as a good communication tool. Get everyone's cell and office number, so you can contact them in emergencies. Don't stay on the phone more than you need to. Make sure you've got text and GPS capacity.

2. Walkie-talkies. Even better in certain circumstances than mobiles.

3. Meals and snacks. Feeding people is important, and it makes them like you more.

4. Driver's license. You could drive for hours, on errands and runs. Have a current license; make sure your company covers you with its insurance. Avoid parking tickets, get to know the area you're driving in, and be comfortable with the vehicle. Keep everything locked up, no matter what.

5. Paperwork. Write everything down. Carry a notebook with you, and put everything down that you're told to do. Keep copies of everything to avoid problems later.

The Top Ten Most Important Tools for PAs and Interns—Cont'd

6. Computers. Several software programs are standards on a production, such as Excel, Word, Final Draft, and Movie Magic, among others. Learn how to use them!

7. The Internet. Know how to search for things you need, like equipment, vehicles, venues, and a dozen other things you'll be asked to find out about.

8. Attire. Pockets in pants and jackets are important for holding phones, pens, stop watches, and other things. Wear comfortable shoes when you're standing or walking a lot, and layer clothing because it gets really hot or very cold on set.

9. Maps. Get familiar with the city or location you're working in. Know the streets, public transportation, and how to get around easily and quickly. Get a portable GPS system or have one on your phone.

10. Production book. Get as organized as you can. You'll have lots of information to deal with so when it's organized into one production book, it's all right there, in one place.

Jonna McLaughlin and Becky Teitel, production managers and former PAs

The Production Design Team

Set designer (construction coordinator). Works with the production designer and creates blueprints for the set(s), hires the crew to construct it, and supervises the assembly of sets, floors, ceilings, or moveable set pieces.

Set dresser. Finds, transports, makes, and/or paints all furnishings, including tables, chairs, appliances, or other furnishings that are part of the action on a set or location. May require working in advance of the next day's shoot, and being on call during the shoot.

Prop master. Supplies all props that are handled as part of the shoot, such as a paintbrush for a home makeover show or a tissue in a crying scene. He works closely with the script supervisor to maintain continuity.

Assistants. Depending on the project, each of the preceding may have one or more assistants working in various capacities.

Wardrobe designer or stylist. Designs the wardrobe “look,” as well as coordinates all wardrobes needed for the shoot with the production designer, buys or rents the wardrobe, measures and fits the talent, keeps all wardrobe elements in the order of the shooting schedule, and regularly cleans and repairs the clothing or costumes. She may sell the wardrobe items after the shoot has wrapped, or handles all wardrobe returns.

Dresser. Works with the wardrobe department to keep track of clothing. Helps the talent change clothing when needed. Some productions may require several dressers who often “swing” between wardrobe, makeup, and hair, unless they are members of a union with regulations that prohibit this multiple workload.

Hair stylist. On set during any scenes that involve talent. The hair stylist may create elaborate high-concept hair styles, design and maintain wigs, or simply be on hand for touch-ups to maintain continuity from one scene to the next.

Makeup artist. Covers a range of needs from applying traditional cosmetic on-camera makeup to creating special effects such as wounds, prosthetics, facial hair, and more. The call time for makeup precedes the shoot time and requires an artist to have an on-set presence.

Additional Production Specialists

Your project might require the hiring of other specialists such as a stunt coordinator, a choreographer, crane and Steadicam operators, on-set tutors, animal wranglers, explosive experts, a teleprompter operator, florists and greens specialists, an on-set nurse, security personnel, and more. Many productions might also call for production support from an accountant, an entertainment lawyer, publicists, and marketing consultants.

The visual effects team. Your project might need a visual effects designer who can create extraordinary effects ranging from magical flying characters to subtle background enhancement. You might want animation or special graphic design for screen credits and a program title, or the illusion of a city blowing away in a tornado. As the producer, you'll make an assessment of your production needs, and then consult with the designers prior to the shoot.

I used to think that being a producer was being the brain because you have to have knowledge of what is going on in all of the other areas. Now I think it is a lot of different peoples’ brains put together. But at times I have thought, am I the only one who is responsible for keeping track of this? Because it seemed like everyone was always coming to me. Then I realized that you do have to delegate. It will make your life so much easier, finding the right people who can take care of things for you.

Valerie Walsh, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

IV. SCHEDULING THE SHOOT

You've chosen your crew, and your script or shooting outline is clear in your mind. Now you're ready to map out your shooting schedule. By using storyboards and sometimes a scheduling software program, the producer can calculate what gets shot, when, and where. The end result is a concise, clear schedule that everyone involved can understand and follow.

A realistic shooting schedule seldom lets you shoot in the exact same sequence as the script—it's too expensive. Unless the project specifically follows one action from beginning to end, most content is shot out of sequence. How a shoot is scheduled has a direct impact on the budget.

The size of your production crew depends on what you plan to shoot. A high-profile sitcom or multiple-location mini-series or episodic requires a larger, more complex crew structure. A documentary or reality-based show, on the other hand, might need only a compact crew that can move quickly and whose members can competently assume multiple duties.

Before you actually shoot, you'll revise your shooting schedule often, based on the following components that are factored into the production's overall structure.

Shooting Format

Producers today can choose between a provocative range of shooting formats. Some commercials and high-concept TV shows are still being shot on 35 mm film, then transferred to digital storage and downloaded into and edited with a nonlinear edit (NLE) system. Most other television shows and new media content are being shot on some format of digital video (DV), including 24P and high def (high-definition television). The question of shooting in digital versus analog seldom applies in today's digital video world. Most all broadcast-quality cameras now shoot a digital signal, which is then fed into an NLE system. More details of shooting and editing are discussed in Chapters 8 and 9.

The rapid expansion of technology in the production of content for TV and new media makes almost anything possible. You can download your video onto the web with a simple click, and can download video from the web into your computer. If you want to project your finished video piece onto a theatrical screen, the final master can be transferred to a film print. Yet, because this technology is continually evolving, some formats are not yet compatible with other systems. Some formats and systems will soon be obsolete, and others are already poised to take their place. Your DP or director is an integral part of the format discussion.

Sets, Sound Stages, and Studios

Your project could call for a complex set, built on a sound stage with backdrops, various room sets or exteriors, enough space to build and paint sets, storage for props, areas for wardrobe, makeup, and production offices. Or, your project may require only a simple set on an inexpensive site. And increasingly, virtual sets are important components in television production as well as feature films; these virtual sets are designed and created on computers and then projected behind the action.

Control is the main advantage of shooting on a sound stage. Here, for example, there's a light grid and the lighting can be regulated without interference from clouds or reflections, and electric power isn't an issue. Outside sounds are nonexistent, and no longer an issue. And, there is enough space for talent, meals, equipment, production administration, and other production needs.

A studio or sound stage may come empty, or be fully equipped with cameras, audio equipment, light grids, and/or crew. Studios have different policies and rate structures. Some may be rented by the half-day, whole day, weekly, or for the duration of the project. In most cases, rates can be negotiated.

Because renting a sound stage can be expensive, try to anticipate all related costs. Build in extra time for changes or mistakes, as well as time for the lighting and electric crews to review the sets before the actual shoot. Most budgets factor in rental time before the shoot—called load in time—and rental time after the shoot, to break down the sets and equipment and clear everything out of the studio.

Locations

Location shooting can add a specific authenticity and mood to the production. And it's generally less expensive than on a sound stage, especially if the location comes with furnishings, props, colors, and/or production space. For example, if you have a certain look you want for a kitchen set, it might be cheaper and easier to find an already-existing kitchen than it is to build one on a sound stage.

But locations can have their downsides, too: space limitations for shooting, production equipment, and areas for the cast and crew. There might be no parking space available, or there is loud construction nearby in the neighborhood. Locations also involve legal agreements, permits, insurance, and fees. You can find an example of a standard location agreement form on this book's web site.

The goal of the production manager and/or producer is to group together all the shots needed in one location before moving the cast, crew, and equipment to the next location. This consolidation is called shooting out your location, and is a primary saver of time, money, and everyone's energy.

The producer considers what time is needed to break down the equipment in one location, move it all to the next location, and set up in the new location. That location might be:

![]() A static location, which can be inside someone's home, an office space, a classroom, store, or an outside shot of a building, garage, baseball field, etc.

A static location, which can be inside someone's home, an office space, a classroom, store, or an outside shot of a building, garage, baseball field, etc.

![]() A moving location, which can include a character on a busy street, shooting a day-in-the-life sequence, or B-roll (extra montage and background footage).

A moving location, which can include a character on a busy street, shooting a day-in-the-life sequence, or B-roll (extra montage and background footage).

Location Scout

A location scout can be a valuable component in finding just the right location. He's familiar with a range of locations: from a suburban home to an urban loft, from exteriors that match with a set on a sound stage to the right interior that suits the production's requirements. Some locations are free; others charge a fee. It is the job of the location scout or manager to find locations, negotiate the best price, and draw up location agreements. The location manager checks that:

![]() The locations are right for the project and reflect a look and texture that's compatible with the production. The location scout takes stills or video of the location for the producer.

The locations are right for the project and reflect a look and texture that's compatible with the production. The location scout takes stills or video of the location for the producer.

![]() A signed location agreement with the owner (or legal representative) of the property is obtained. Some locations charge a fee, but others are free. Verify that the production carries adequate liability insurance to cover any damages in the course of the production. At the completion of the shoot, the property owner signs a release agreement.

A signed location agreement with the owner (or legal representative) of the property is obtained. Some locations charge a fee, but others are free. Verify that the production carries adequate liability insurance to cover any damages in the course of the production. At the completion of the shoot, the property owner signs a release agreement.

![]() Whenever possible, the locations are close to one another.

Whenever possible, the locations are close to one another.

![]() The location can supply adequate electrical power; if not, a generator must be brought in.

The location can supply adequate electrical power; if not, a generator must be brought in.

![]() There is enough space to accommodate crew, talent, catering, and equipment.

There is enough space to accommodate crew, talent, catering, and equipment.

![]() The necessary production equipment can fit into the location, and that there are elevators, ramps, and/or loading docks.

The necessary production equipment can fit into the location, and that there are elevators, ramps, and/or loading docks.

![]() The location can be lit adequately, either with natural light or supplied light.

The location can be lit adequately, either with natural light or supplied light.

![]() The audio in the location has minimal noise interference from traffic, neighbors, animals, conversations, machinery, air conditioning, schoolyards, or construction.

The audio in the location has minimal noise interference from traffic, neighbors, animals, conversations, machinery, air conditioning, schoolyards, or construction.

Foreign Locations

Shooting in a foreign location can lend additional depth or mood to the project. Or, it might be part of the show's plotline or theme. Foreign locations can be less expensive if they offer professional local crews with lower pay scales, regional tax incentives, or a strong currency exchange rate. Locations such as Canada, South America, Eastern Europe, Australia, Iceland, and New Zealand can help the producer stretch the budget as well as provide viable locations. In some countries, the weather patterns can also extend a shooting season.

Exterior and Interior Shots

Most producers prefer to shoot their exteriors, or outside shots, before they shoot anything else. An exterior may be a master shot of an apartment building, a park, or a crowd shot on a busy street. When these exteriors are shot, the production can move on to the interior, or inside shots, with more security. The exteriors are necessary to establish where an interior shot is taking place. For example, when the outside of an apartment building is shown, we know that the next scene we see inside an apartment takes place in that building.

Any number of factors can get in the way of shooting your exterior shots. There's a snowstorm or an earthquake, or a freak fire burns down the vacant building you planned to use, or there's a power blackout. It's happened, so I always have a backup plan—how can I use the cast and crew I'm paying while I figure out my next move? My Plan B is almost always a cover set, an alternative interior location that has been prepped and dressed for shooting a back-up scene. This Plan B has saved the project, the budget, and my reputation.

![]()

Day and Night Shoots

A night shoot can be integral to the storyline—it creates dramatic textures and nuance. It can also increase your budget and overall workload. Night shoots require specific lighting and equipment, permits and traffic routing, and put an overall burden on scheduling crews who often have to shoot at night as well as in the daytime. Following is a list of ways for the producer to ease this burden.

![]() The look of nighttime can be achieved by shooting during the day, by blacking out or relighting the windows to give the appearance of night behind the action.

The look of nighttime can be achieved by shooting during the day, by blacking out or relighting the windows to give the appearance of night behind the action.

![]() The producer can schedule all the night shoots consecutively, building in a break for the crew and talent before switching back to a daytime shooting schedule.

The producer can schedule all the night shoots consecutively, building in a break for the crew and talent before switching back to a daytime shooting schedule.

![]() A producer also might divide the day and night shooting into splits, a half-day and half-night schedule.

A producer also might divide the day and night shooting into splits, a half-day and half-night schedule.

Actors and Talent

Depending on the contract you've negotiated with the actors’ unions, actors must be paid overtime after they've worked for a specified number of hours, usually eight or ten. So, the crew sets up the equipment before the shooting starts, and then breaks it all down after the actors have finished their work. Crews are usually booked for longer shifts to accommodate the talent, so scheduling talent and crew requires a review of the big picture—what needs to be shot and when, what union rules might govern certain decisions, and then balance that with the crew and their needs. This approach also pertains to most non-union shoots.

Other talent-related factors you want to take into consideration when you're scheduling include:

![]() Child actors. Union rules require that children have a shorter working schedule, and must have a tutor, parent, or social worker with them at all times, especially if the talent is missing regularly scheduled school time.

Child actors. Union rules require that children have a shorter working schedule, and must have a tutor, parent, or social worker with them at all times, especially if the talent is missing regularly scheduled school time.

![]() Animals. Using an animal in a shoot requires a special trainer who can prompt it to do tricks and stunts, and who supervises the animal between takes. Whenever any animal is on set, the American Humane Association (AHA) must be notified. This mandate even extends to cockroaches.

Animals. Using an animal in a shoot requires a special trainer who can prompt it to do tricks and stunts, and who supervises the animal between takes. Whenever any animal is on set, the American Humane Association (AHA) must be notified. This mandate even extends to cockroaches.

![]() Extras and crowds. The producer in charge of the extras will often audition them or find them through other means. Then, she'll schedule their call time on set, arrange a comfortable waiting area, give them the proper release forms to fill out, and decide who needs wardrobe, hair, and/or makeup. While they wait for their scene, extras are provided with food, water, and bathroom facilities; they are usually rehearsed before the shoot.

Extras and crowds. The producer in charge of the extras will often audition them or find them through other means. Then, she'll schedule their call time on set, arrange a comfortable waiting area, give them the proper release forms to fill out, and decide who needs wardrobe, hair, and/or makeup. While they wait for their scene, extras are provided with food, water, and bathroom facilities; they are usually rehearsed before the shoot.

![]() Stunts. The stunt category can include tripping on the stairs, a car chase, explosions, gunshots, falls from buildings, and fist fights. An effective stunt requires careful design, test runs, and rehearsals, and is generally performed by professional stunt men and women. Stunt work requires rehearsal time as well as fees and additional insurance.

Stunts. The stunt category can include tripping on the stairs, a car chase, explosions, gunshots, falls from buildings, and fist fights. An effective stunt requires careful design, test runs, and rehearsals, and is generally performed by professional stunt men and women. Stunt work requires rehearsal time as well as fees and additional insurance.

![]() Convenience vehicles. Some productions require mobile dressing rooms, portable bathrooms, and craft service trucks. The transportation captain is in charge of locating the vehicles, negotiating fees, and arranging for their call times on the production. If extra insurance is necessary, that information is given to the producer, line producer, or UPM.