CHAPTER

8The Shoot: Production

Hell, there are no rules here—we're trying to accomplish something!

Thomas Edison

THIS CHAPTER'S TALKING POINTS

| I. | The Producer's Role |

| II. | On Set and On Location |

| III. | The Camera |

| IV. | Lighting |

| V. | Audio |

| VI. | The Actual Shoot |

I. THE PRODUCER'S ROLE

Experience is the name everyone gives to their mistakes.

Oscar Wilde

As the producer, you've carefully developed each stage of your project. Now, you're ready for the actual shoot. Your vision is about to become tangible and visible. Your production schedule might be ambitious, stretching over a few weeks. Or maybe it's a simple, small, and compact two-day shoot. No matter its size, there are always details involved.

When the components are in place, the writer, director, crew, and talent are prepared to collaborate in making this project come alive. The actual shooting, also called principal photography, can begin when everything is ready to go: the script has been finalized; the actors rehearsed, made up, and costumed; releases have been signed; the sets built; the crew hired; the equipment is up to speed; all locations are secured; and any other details are all in place.

The Producer's Team

The producer depends on, and is a part of, a team of professionals who are also individuals, each with his or her own style and personality. You want to respect their talents, skills, and moments of real genius, and to be graceful about their human mistakes and mishaps. Successful creative teams often have a history of working together; some producers formed their team early on, as students or interns on a job.

A team can be many people, or just a few; each project's size and budget determines how many people can be part of your team. Your team might be just a camera person and an audio engineer with whom you've worked for years, and who give their best every time you shoot together. Or your team may include your client who believes in your vision, or the actors or on-camera talent who always come through for you. Your team often includes other producers, the production manager, designers, editors, whomever is needed for each specific project.

The producer's team succeeds through mutual trust, respect, humor, and a shared vision. The difference between the “creative” and the “technical” teams is a nonissue. You want the people with whom you work to fit both descriptions, translating your ideas with their skills and the tools of their trade into a true synthesis of art and science.

As the producer, you'll usually have the final word in decision-making, factoring in suggestions from the production team, the client's notes and requirements, and your own goals. Only after all these parts of the equation have been factored together do you make final decisions about production.

Production Protocol and Politics

In almost all television and new media projects, the producer takes an active part in the actual production. The producer keeps everyone focused on their job, knows who is doing what job, stays on top of what needs to get done, and clearly communicates everyone's area of responsibility.

If a director has been hired, the producer makes sure that all the elements are in place so the director can move ahead. As a producer, you can work closely with your team by:

![]() Explaining your ideas and the vision of the project

Explaining your ideas and the vision of the project

![]() Agreeing on the vision and the creative directions it's taking

Agreeing on the vision and the creative directions it's taking

![]() Communicating frequently and openly with your team

Communicating frequently and openly with your team

![]() Listening to ideas and suggestions from your team

Listening to ideas and suggestions from your team

![]() Nourishing your team with praise, food, and enthusiasm

Nourishing your team with praise, food, and enthusiasm

![]() Providing a model of collaboration and mutual respect

Providing a model of collaboration and mutual respect

II. ON SET AND ON LOCATION

Action springs not from thought, but from a readiness for responsibility.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

In the previous chapter, you explored the pros and cons of shooting on a set/sound stage and on location. Each of these options can serve you well, depending on the nature of your specific project and its budget. Now, more producers are looking at another increasingly popular alternative to shooting on sound stages and on location – “building” a virtual location.

Virtual Locations

Shooting on location or on a sound stage each has its advantages and limitations, as we saw in Chapter 7. Maybe neither can be negotiated to fit the budget, or isn't available, or can't be duplicated on a sound stage. You can visualize this location, but you can't find its real-world equivalent. An alternative is to use a virtual location, designed and created through computer-generated imagery (CGI) capable of contributing a range of creative images—a futuristic building, a vast country landscape dotted with sheep, or an ancient battleground with thousands of charging warriors. It all looks real but it's virtual.

Virtual locations and CGI wizardry can be seen in a variety of looks and uses in most television programs, feature films, high-end commercials, news broadcasts, sports events, and video games, and is continually branching out to all platforms and content.

Building these virtual locations starts with a blue screen or a green screen background (also called a chroma key backdrop), or more recently, a silver screen with millions of tiny glass beads that reflect a light ring placed around the camera's lens. These screens can be hundreds of feet long, or simply 8′ × 8′ mobile traveling screens that can easily be folded up and transported. Whichever screen you decide on is then placed behind the action you're shooting. That action is edited later onto another image that replaces the blue, green, or silver screen.

Let's say… that the script calls for an actor to topple over a high iron railing and plunge into Niagara Falls. First, the railing and surrounding set is built on a sound stage. Then, in a medium shot, the actor plays out the scene and falls over the railing, onto a heavy pad that's not in the shot. This action is all shot in front of a special blue, green, or silver screen that fills up the frame. Meanwhile, a camera crew goes to Niagara Falls and shoots the actual waterfalls at an angle that will match up with the action of the actor in the studio. Then, the two scenes are layered together in the editing room. The result is a seamless edit that looks as though the actor really tumbled over Niagara Falls. It's realistic, cheaper expensive than shooting the whole scene on location, and nobody gets hurt.

Other locations can be built entirely on the computer, and don't require the shooting of any footage. Designed and created by a graphic designer, this kind of virtual location can be an elaborate rendition of a futuristic city skyline, a landscape from prehistory, an unknown galaxy. Even an actual photograph, say, of an historical time period, can act as a backdrop for live action or for CGI figures.

III. THE CAMERA

Where observation is concerned, chance favors only the prepared mind.

Louis Pasteur

The camera is the primary tool that producers use to tell a story. And although the use of 16- and 35-mm film is still a presence in television programming, digital video technology is growing at such a rapid rate that the merger of film and video in television has essentially arrived. So, for the purposes of this text, digital video is the format of choice. You can consult additional sources and reference material for shooting and/or editing your production in film, and to update information on digital cameras, lenses, and accessories.

The camera operator (also called the shooter) forms a close bond with the camera to compose an image that tells a story, and shoots footage that not only looks good but is of high technical quality and can be easily cut together with other footage shot.

Today's video cameras are sophisticated, comparatively inexpensive, and more and more flexible. Most cameras offer creative options such as choices of formats on which to store the footage and audio, lenses, in-camera settings, varying shutter and shooting speeds, and built-in optical illusions.

Shooting with Digital Video

Think back to the Technicolor films from the 1950s. In Technicolor, negatives were processed into three separate red, green, and blue negatives. Ordinary film processing used only one negative with no color separation in the negatives, but the Technicolor prints made from the three-strip process had vivid, memorable color and resonance.

Now, in much the same way, a mid- to high-range video camera separates the light that hits the lens into three components of color: red, green, and blue (RGB). These three-chip cameras have three separate charge-coupled devices (CCDs) that produce a sharper, higher quality color picture, essentially three times better picture quality than from single-chip, lower-end cameras. Most popular digital cameras capture images using these CCD sensors. However, an increasing number of high-end television and film projects are being shot with cameras that relay on CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) sensors, a more sophisticated version of CCD sensors.

Digital Storage

Each image with its audio is processed as an electrical signal that can be recorded onto a storage medium like digital videotape, P2 memory cards, a hard drive device (HHD), and flash memory. Often, the videotape is fed via a system like FireWire or USB 2.0 directly onto the computer's hard drive.

All these recording formats work. Each has its own creative, technical, and budgetary advantages, and each has its limitations. Superior systems are being developed at a furious pace, and undergoing beta and field tests as you read these words. The hot item on today's top-ten list could be a big yawn tomorrow.

How you get the video into your editing system is as important as how you shoot it. If your editing system can accommodate a digital signal, or has a FireWire input (and most do), then you're best shooting with a DV camera. Your final decisions about what cameras to use, and in what shooting format, are best made with your DP or cameraman/woman. The bottom line is that you want your project to be shot professionally, in broadcast-quality video, with the highest quality and for the best cost that you can manage from your budget.

Shooting High-Definition Video

The increasingly advanced digital technology of high-definition television (HDTV) has created an extraordinary leap in how we view and produce content and programming. HD has been heralded as a revolution because it can “see” better than the human eye with its depth of field, brilliance of color, and its image clarity. Often, HD can see too much—every petal on a red rose may be crystal clear, but so is every wrinkle on an actor's face and each badly painted set that might have gone unnoticed in film or standard definition video.

HDTV has arrived in full force. In America, the majority of prime time programming is regularly broadcast in HD, as are many local and national sports specials and events, such as the Academy Awards. Compared to the traditional U.S. analog system that broadcasts NTSC programming in 525 horizontal lines, an HD image has either 720 or 1080 lines, depending on the specific HD format. This difference results in a higher resolution and a clearer picture. And, increasingly, many cameras are equipped to shoot in HD as well as standard definition, 24p, and other formats like 2K, 4K, and 6K scans.

HDTV Systems

Currently, at least 18 versions of HDTV are used in various parts of the world. Two, however, have emerged as the most popular: 720p and 1080i. There are arguments for each system, though HD sets display both equally well in a widescreen 16:9 format. This shape is rectangular, with more picture space on the sides. Compare the size of this screen to the traditional 4:3 TV set, which is nearly square. The 16:9 format TV set is sold almost exclusively now, and the majority of television-bound programming is shot in 16:9, not 4:3.

![]() 720p. (1280 pixels per line and 720 progressively-scanned lines) Works well for broadcast, though it's usually not recommended for a project that may be transferred later to film, or projected on a large screen.

720p. (1280 pixels per line and 720 progressively-scanned lines) Works well for broadcast, though it's usually not recommended for a project that may be transferred later to film, or projected on a large screen.

![]() 1080i. (1920 pixels per line and 1080 actively-interlaced lines of resolution) Best used when the final product calls for a “reality” aspect, which looks as if the viewer is seeing it live, in vivid sharp detail.

1080i. (1920 pixels per line and 1080 actively-interlaced lines of resolution) Best used when the final product calls for a “reality” aspect, which looks as if the viewer is seeing it live, in vivid sharp detail.

Shooting in 24p Video

When you shoot in 24p (24 frames per second, progressive scan), the process involves video that runs at 24 fps, the same rate as film, with an intermittent flash of black in every frame cycle. Put simply, 24p has a look that is similar to film. It's softer, it has a film “flicker,” the colors appear richer than in video, and because it can be shot in both standard and high definition, it's a popular format for shooting, especially for producers who might want the option of transferring their project to 35-mm film for projection purposes.

Before shooting in 24p, talk with your editor and DP. Many cheaper DV cameras have a 24-frame mode but the camera is actually shooting 30 frames; the shutter is only mimicking 24 frames. If you shoot some of your footage in 24 frames per second, and other footage for the same project in 30 frames, you could find yourself in real trouble when you get into the edit room. Because of certain technical limitations, few NLE systems currently can accommodate both formats at the same time.

The majority of producers, editors, and technical experts agree that most projects should be finished in HD with a 24p 16:9 master. It is the best format for broadcasting, progressive streaming on the web, creating PAL versions for broadcast in Europe and other PAL-friendly countries, and for release on DVD. Yet, considering the rapid growth in digital technology, check with your DP or cameraman/woman for their opinion on your specific project.

Choosing Your Camera

Unless you're shooting in film, video cameras today are almost always digital—even the inexpensive home movie cameras. A professional-quality camera is within anyone's budget to purchase, or at least cheap enough to rent, for your shoot. Anything less cheapens the quality of your footage and ultimately does a disservice to your vision.

Budget-Conscious Cameras

The rapid evolution of digital technology is quite evident in the proliferation of excellent professional-quality, or prosumer, cameras and a range of peripheral equipment. These cameras tend to be reasonably priced (anywhere from $1,000 to $9,000), and work perfectly fine for most productions—from documentaries and news gathering, to shorts, commercials, music videos, content for online and cellular delivery systems, and even features. Add to this the computerization of the editing process, and shooting your project can be manageable, and inexpensive.

As of the writing of this second edition, certain cameras stand out because of their distinct technological advances. Camera operators want a camera with functions such as manual focus, manual aperture and shutter speed control, a LCD monitor that folds out, control over the white balance function, the capacity to accommodate an external mic, and can output video to the computer.

Digital cameras can now digitally record both the image and the audio onto a variety of formats. The most popular formats include hard-disk drive, flash memory card, mini-DV tape, and DVD disk; some cameras are hybrid and can record video onto either a DVD or a second medium (such as flash memory or hard-disk drive).

Some cameras are more suited to the professional shooter, whereas others work just fine for the producer/editor (also called a preditor) who researches, shoots, and edits her own news segment or documentary. All are digital broadcast-quality, work within most budgets, and reflect the most popular cameras currently being used by professionals. As always, check with your DP or camera operator about the best one for your project.

High-End Cameras for Digital Cinematography

This is a category of more expensive and complex cameras, generally focused on independent films and specific television programs with an accommodating budget and other needs beyond the parameters of usual television and new media programming.

These cameras tend to have a single-chip CMOS sensor, a successor to the CCD image sensors in most digital cameras. This allows the camera to duplicate the shallow depth of field and overall look of 35 mm, and with some cameras, shoot in 65 mm. The majority of these cameras can also accommodate professional film camera mounts and lenses. Most capture image and audio onto tape, hard disks, and flash memory; some can capture onto 2K, 4K, and 6K files.

At the moment, the cameras most prominent in this growing area of digital cinematography are:

![]() Arri's Arriflex D-20

Arri's Arriflex D-20

![]() Dalsa Origin

Dalsa Origin

![]() GS Vitec noX

GS Vitec noX

![]() Panavision's Genesis and Varicam

Panavision's Genesis and Varicam

![]() Silicon Imaging's SI-2K

Silicon Imaging's SI-2K

![]() Sony's F23 CineAlta

Sony's F23 CineAlta

![]() Red's Red One and Scarlet

Red's Red One and Scarlet

![]() Thomson Viper FilmStream

Thomson Viper FilmStream

![]() Vision Research Phantom 65 and Phantom HD

Vision Research Phantom 65 and Phantom HD

Studio Cameras

It's like a mini Saturday Night Live to see them with the cable pullers, everyone getting from Point A, which could be home base, all the way over to [Point B]…it doesn't sound like a lot, but during the commercial break, that's a fascinating thing to watch.

Laurie Rich, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

When shooting a talk show or news broadcast, for example, larger DigiBeta cameras are the traditional camera of choice. Most are mounted on moving balanced pedestals that keep the camera stationary; these pedestals can glide smoothly around a limited set, with a feature that can tilt the camera up or down. Most studio-based productions require three to six pedestal cameras, as well as one or two cameras mounted on a swooping jib, or crane, that can fly over the audience and onto the set. Some productions might augment the DigiBeta cameras with a hand-held camera that moves freely; all the cameras are directed by the director from within the control room. Microphones are suspended at regular distances over the audience for their reactions, like laughter and applause.

In a typical multicamera studio shoot, the footage from each camera, as well as the audio from the talent and audience microphones, are all fed into a central control room that is close to the set (or fed to a mobile truck with its own control room). In the central control room the director, producers, technical director, audio mixer, and graphics person all watch each incoming camera feed on its designated monitor. As the crew in the control room records the footage, it is generally edited live. This process is called live to tape, and it's how most studio shows are produced. Any additional editing changes can be made later. Or, it's all recorded to tape and edited at another time.

Time Code

When you're shooting video professionally, the camera “burns” a time code (TC) signal onto the videotape (or whatever format you're recording onto) and assigns each frame a specific number. You can draw a direct analogy between video and time code in video, and sprocket holes and frame numbers in film. The time code is broken into four sections. If, for example, the time code number is 07:02:45:17, then:

![]() 07 is the hour

07 is the hour

![]() 02 is the minutes

02 is the minutes

![]() 45 is the seconds

45 is the seconds

![]() 17 is the exact frame number (there are 30 frames per second); these last two numbers aren't necessary when taking most notes, only in editing when frame-accuracy is necessary

17 is the exact frame number (there are 30 frames per second); these last two numbers aren't necessary when taking most notes, only in editing when frame-accuracy is necessary

Working with time code is an integral tool for the editor as part of the editing process. It makes the editing frame-accurate and exact. TC is also a valuable tool for producers when screening and logging footage prior to the edit session. As seen in Chapter 9, you can use TC numbers to create a storyboard, or paper cut, that the editor uses as a “script” for the edit.

Taking Notes with Time Code

To screen your footage, it must first be dubbed to DVD with the TC displayed visually on the top or bottom of the screen; this is called visible time code, or vizcode. The TC is exactly the same as on your original footage, and known as matching time code. As you screen the dubs, you'll make notes using TC as your reference points.

Let's say… you're screening footage that you've shot for a 10-minute short, and you're putting together a paper cut to give to your editor. On Tape #1, the teenage boy opens the door at 00:03:04:15, and it's a medium shot. Then, you find the close-up of his hand on the doorknob, which is on Tape #4 at 00:06:13:15. These two scenes were shot at different times, and each comes from a different tape but both need to be edited together later. Time code helps you and your editor match them together, perfectly.

As you screen each tape, you'll want to take good notes of what you see and hear; this is called logging. As you watch each tape from start to finish, log the TC that describes specific parts of the footage, such as a great cutaway shot, a move from one location to another, the best take of one scene, and so on. Everyone has a personalized system—some people write the shot descriptions, like CU for close-up, WS for wide shot, and so on. Often people also mark the direction in which the action is going; for example, a bird flying to the right could be marked with >, a pair of eyes looking up is ^, and a camera pan from right to left could be marked as <<<.

From these notes, you can create a paper cut (storyboard) for editing. It shows the TC numbers, scene descriptions, length of scene, and which tape each scene is on. This paper cut is a major time-saver. As you refine your own system, you can read your log at a glance and find your shots. You'll find logging and storyboard forms on this book's web site.

Setting Camera Time Code

On a shoot, there are two ways to set and record TC in the camera:

1. A studio multicamera shoot. All the cameras are linked into the “house” TC generator. This sends out time-of-day time code (TC that records the actual time of day) to all cameras and tape machines, simultaneously, and is located in the control room on the engineering console. This way, the tapes from each camera can be “synced up” (synchronized) in the edit room. This system is helpful in organizing notes based on the chronology of events that occurred during the shoot. It also simplifies the editing, making it easier for the editor to match up each camera's footage simultaneously.

Without this synchronization, the editor wastes time and money going back and forth to each tape and trying to keep video and audio in sync. Not all cameras can take in outside time code, especially low-budget DV cams, so one way to achieve some form of sync, once you've turned all your cameras on, is to keep them all running together. Turn them on and off together on the count of three.

IN THE TRENCHES…

I can virtually guarantee you that attempting a multicam shoot without matching time code will make your editor extremely cranky. Trying to edit different camera feeds together without the same time code using only his blood-shot eye ball? It can be done, but it's pure hell. What's a viable Plan B? Bring an LCD time code reader to the set— it displays the hour, minutes, seconds, and frames per second (00:00:00:00). Before and after each time the cameras roll, each camera shoots the TC reader. This may not make your editor any less grumpy but at least you've given him a reference point. He can use the multisync function in his edit programs to keep all the cameras in sync.

![]()

2. A single-camera shoot. An internal TC generator can be set inside the camera itself. Producers usually start Tape 1 at Hour #1 (01:00:00:00), Tape 2 at Hour #2 (02:00:00:00), and so on. Because there are only 24 hours in a video day, TC numbers beyond 23:59:59:29 don't exist. However, Tape 24 can be set at 00:00: 00:00 and Tape 25 at 01:00:00:00, and so on. This system helps in logging and screening footage for the edit session later.

Capturing the Image

Prior to shooting, the producer, director, and/or the DP discuss the creative and technical options for shooting each scene. Their decisions work with the narrative flow, affect the style and pace of the program, and ultimately will guide how a viewer sees a story line or character. The perspective of a shot, for example, can convey dramatic tension or character motivation when the viewer knows from whose perspective the story is being told. This perspective is either objective or subjective.

![]() Objective perspective. Captures the viewpoint of an unseen narrator or storyteller who is an onlooker, and views the characters from a third-person viewpoint. The shot is often a wider, more distant shot or a two-shot.

Objective perspective. Captures the viewpoint of an unseen narrator or storyteller who is an onlooker, and views the characters from a third-person viewpoint. The shot is often a wider, more distant shot or a two-shot.

![]() Subjective perspective. Tells a story from a character's first-person point of view. The shot is closer or tighter, such as a close-up or an over-the-shoulder shot.

Subjective perspective. Tells a story from a character's first-person point of view. The shot is closer or tighter, such as a close-up or an over-the-shoulder shot.

When planning a shot, the primary factors that play into capturing the image in the shoot include:

![]() Framing and composition

Framing and composition

![]() Camera angles

Camera angles

![]() Camera moves

Camera moves

![]() Camera lenses

Camera lenses

![]() Camera shot list

Camera shot list

Framing and Composition

The primary concept of framing a shot involves shooting an image—a person or an object—as well as everything that surrounds or affects the image. An extreme close-up of a face gives one kind of narrative message, and an extreme long shot of the same person tells a different story altogether. Each option frames the image and composes the frame around it.

Composition is the relationship of objects to each other in the frame, or to the shape of the subject being shot. Colors, lighting, scenery, props, and camera blocking all contribute to a scene's composition. This total effect is known as mise-en-scene, or the setting up of a scene.

Another important aspect of framing concerns whether your project will be shot and/or viewed on either a 4:3 format or 16:9. Because both are feasible, consider shooting your primary action in the middle of the frame, with less important details on both sides in case they get cut off.

Camera Angles

Each time the camera moves, and every angle at which the camera is placed relative to what it's shooting, creates a different effect, both visually and thematically. A sitcom can be shot in a fixed frame, using a stationary or locked down camera on a tripod, and the actors move only within that framing. A gritty detective drama might use a handheld approach, moving fluidly in and out of the characters’ faces and actions. Both the genre of your show and its content help determine how you'll shoot it. As you decide on camera angles and movement, keep two things in mind:

![]() Viewpoint. The height of the camera's position determines the viewpoint of the character, and gives the viewer a sense of theme and direction. When shot from below, for example, a character has the illusion of superiority, whereas a character shot from above may seem inferior or small. When an actor speaks directly into the camera, the dialogue is directed to the viewer; when the actor looks off to the right or the left of the camera's lens, it appears that he is focusing on something else.

Viewpoint. The height of the camera's position determines the viewpoint of the character, and gives the viewer a sense of theme and direction. When shot from below, for example, a character has the illusion of superiority, whereas a character shot from above may seem inferior or small. When an actor speaks directly into the camera, the dialogue is directed to the viewer; when the actor looks off to the right or the left of the camera's lens, it appears that he is focusing on something else.

![]() Eye-line. The position of the camera needs to correspond to the character's eye-line, usually in the top third of the frame. The viewer should be able to follow what the actor sees to the actor's eyes. This guarantees that the eye-lines from one character to another match up in editing.

Eye-line. The position of the camera needs to correspond to the character's eye-line, usually in the top third of the frame. The viewer should be able to follow what the actor sees to the actor's eyes. This guarantees that the eye-lines from one character to another match up in editing.

Camera Moves

Your camera can be a flexible tool for capturing the subtleties of an image or the flow of action. The traditional camera moves from which a camera operator can choose include:

![]() The tilt. A camera can maintain the same eye-line, and tilt down (giving the impression of the subject looking toward the ground) or tilt up (suggesting that the subject is looking toward the sky). This tilt can also give an impression of a subject's inferiority or superiority to another character or to the viewer.

The tilt. A camera can maintain the same eye-line, and tilt down (giving the impression of the subject looking toward the ground) or tilt up (suggesting that the subject is looking toward the sky). This tilt can also give an impression of a subject's inferiority or superiority to another character or to the viewer.

![]() The Dutch (or canted) angle. Often used in reality shows and interviews, the camera is rotated so that the image itself appears at an angle, and creates a sense of intimacy or tension.

The Dutch (or canted) angle. Often used in reality shows and interviews, the camera is rotated so that the image itself appears at an angle, and creates a sense of intimacy or tension.

![]() The pan. The camera swivels on the tripod or on its axis to form an arc from right to left or left to right. A pan is smooth and even-paced. A swish pan moves faster and can be effective in action sequences or as transitions in editing.

The pan. The camera swivels on the tripod or on its axis to form an arc from right to left or left to right. A pan is smooth and even-paced. A swish pan moves faster and can be effective in action sequences or as transitions in editing.

![]() The tracking shot. Also known as a traveling shot, it pulls the viewer into the action by using a camera mounted on a dolly that moves either on tracks or on special shock-resistant wheels alongside a moving subject. The same effect can be accomplished by mounting a camera on a crane or a jib that swoops above, into, or away from the action in a scene. Another effective approach is a camera rig (such as Steadicam, Glidecam, and the DvRigPro) that's worn by the camera operator for shooting smoothly in any direction.

The tracking shot. Also known as a traveling shot, it pulls the viewer into the action by using a camera mounted on a dolly that moves either on tracks or on special shock-resistant wheels alongside a moving subject. The same effect can be accomplished by mounting a camera on a crane or a jib that swoops above, into, or away from the action in a scene. Another effective approach is a camera rig (such as Steadicam, Glidecam, and the DvRigPro) that's worn by the camera operator for shooting smoothly in any direction.

![]() The zoom. The camera lens—in a zoom-in—moves smoothly into a close-up of a person or object. A zoom-out starts close and moves back.

The zoom. The camera lens—in a zoom-in—moves smoothly into a close-up of a person or object. A zoom-out starts close and moves back.

![]() Extending the frame. The camera is locked down and stationary, and holds on an object or scenery for a few beats, possibly with off-screen sound effects like a ringing phone, or a closing door before or after the character enters the frame from right or left.

Extending the frame. The camera is locked down and stationary, and holds on an object or scenery for a few beats, possibly with off-screen sound effects like a ringing phone, or a closing door before or after the character enters the frame from right or left.

Camera Lenses

Another area of discussion with your DP is about what lenses can be used in the shoot. In some cases, a wide-angle lens can add a more spacious feeling to a shot, whereas a fish-eye lens creates a subtle distortion that can be interesting when shooting buildings or interiors that are otherwise mediocre. A close-up lens can give a clear focus on a small object. Other lenses can add diffusion or hues of color.

Camera Shot List

Prior to the shoot itself, a shot list is created and distributed. This is an inventory of each shot needed to be shot for a specific sequence or scene, and uses specific terms for each camera angle, such as ECU for extreme close up, and so forth. The elements that go into a shot list are discussed and illustrated in Chapter 7; a shot list template can be found on this book's web site.

Today's technology is advancing camera design so rapidly that cameras and their formats can upgrade, or become obsolete, in a matter of months; some formats will survive as others disappear. Ultimately, you'll talk with the DP and director, and often the editor, about which camera options are best suited to your particular project.

IV. THE LIGHTING

A picture must possess a real power to generate light…for a long time now, I've been conscious of expressing myself through light or rather in light.

Henri Matisse

Lighting is an essential tool for painting and enhancing the video image. The subtle use of light creates atmosphere and mood, dimension, and texture. It can help to convey a plot line, enhance key elements such as set color or skin tone, and signals the difference between comedy and drama, reality and fantasy.

Hard versus Soft

All lighting falls into either “hard” with sharp and distinct shadows, or “soft” with less defined, softer shadows and fewer background images. The intensity and clarity of the bulb, or its diffusion, combines with placement to design a shooting environment.

![]() Hard light. Aimed directly on its subject, with a brighter single-source illumination. The sun is one example. Other hard light is incandescent, ellipsoidal, and quartz.

Hard light. Aimed directly on its subject, with a brighter single-source illumination. The sun is one example. Other hard light is incandescent, ellipsoidal, and quartz.

![]() Soft light. Diffused, created with less intense lamps that reflect or bounce light off a reflector, a ceiling, or another part of the set. Soft lighting effects are enhanced with scrims, strips, scoops, and banks.

Soft light. Diffused, created with less intense lamps that reflect or bounce light off a reflector, a ceiling, or another part of the set. Soft lighting effects are enhanced with scrims, strips, scoops, and banks.

Three-Point

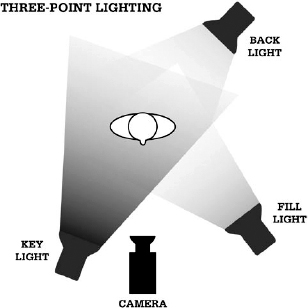

Production lighting involves three major lights and their positions in relation to each other (three-point lighting):

![]() Key light. Powerful, bright light that best defines a primary, or key, person or object, creating a deep shadow. It is positioned at roughly a 45 degree angle to the subject being shot.

Key light. Powerful, bright light that best defines a primary, or key, person or object, creating a deep shadow. It is positioned at roughly a 45 degree angle to the subject being shot.

![]() Fill light(s). Softer light placed at an angle to “fill” any unwanted shadows created by the key light, at about half the key's intensity. It is usually placed opposite the key light at about a 30 degree angle

Fill light(s). Softer light placed at an angle to “fill” any unwanted shadows created by the key light, at about half the key's intensity. It is usually placed opposite the key light at about a 30 degree angle

![]() Back light(s). Throwing light on the subject from behind, it's positioned behind at around a 90 degree angle; it can also be adjusted higher or lower to create other lighting moods. This helps to create an illusion of depth behind the main subject and brings it forward from the background.

Back light(s). Throwing light on the subject from behind, it's positioned behind at around a 90 degree angle; it can also be adjusted higher or lower to create other lighting moods. This helps to create an illusion of depth behind the main subject and brings it forward from the background.

High-Key versus Low-Key Lighting

Most TV talk shows, sitcoms, variety shows, musicals, and family entertainment use high-key lighting: a high ratio of key light to fill light. Low-key lighting creates a more dramatic, moody, and textured effect for dramas, documentaries, music videos, and others.

Hot and Cold Lighting

All lights have a color temperature that influences what the camera records:

![]() Daylight (outdoor). The most powerful and brightest light. Daylight is hot and produces a blue tone on video.

Daylight (outdoor). The most powerful and brightest light. Daylight is hot and produces a blue tone on video.

![]() Artificial (indoor). Considered cold. On video, it creates a reddish yellow cast.

Artificial (indoor). Considered cold. On video, it creates a reddish yellow cast.

Interior and Exterior Lighting

Everything you shoot is either indoors or outdoors. Each light has its advantages and limitations.

![]() Exterior lighting. As you shoot an exterior (outdoor) scene, you may want the spectacular intensity of the sun at high noon. Or, the scene calls for the moody waning light immediately after sunset, known as the magic hour. Each option has its own effect on an exterior scene. However, outdoor shooting can pose real challenges. Along with the sun's continual movement, its degrees of brightness can fluctuate dramatically through the shooting day. When the sun is your key light, it might need to be partially blocked out or augmented by fill lights or back lights. An exterior set can be shot at night but lit to look like daylight, or vice versa.

Exterior lighting. As you shoot an exterior (outdoor) scene, you may want the spectacular intensity of the sun at high noon. Or, the scene calls for the moody waning light immediately after sunset, known as the magic hour. Each option has its own effect on an exterior scene. However, outdoor shooting can pose real challenges. Along with the sun's continual movement, its degrees of brightness can fluctuate dramatically through the shooting day. When the sun is your key light, it might need to be partially blocked out or augmented by fill lights or back lights. An exterior set can be shot at night but lit to look like daylight, or vice versa.

![]() Interior lighting. Shooting interior (indoor) scenes poses fewer challenges as video cameras and shooting formats become more advanced and light-sensitive. A camera's iris, for example, can play with light and color and go from automatic to manual. This avoids the camera's normal tendency to focus on the best-lit object in the scene.

Interior lighting. Shooting interior (indoor) scenes poses fewer challenges as video cameras and shooting formats become more advanced and light-sensitive. A camera's iris, for example, can play with light and color and go from automatic to manual. This avoids the camera's normal tendency to focus on the best-lit object in the scene.

Both interior and exterior lighting can be adjusted by using reflectors (also called bounce cards). These are glossy, white lightweight cards in various sizes that reflect light onto an object or actor. Large silks (squares of translucent material) can be strategically hung and positioned to filter the sunlight and maintain lighting consistency. In some cases, a light-filtering paper gel called neutral density (ND) is placed onto windows to keep outside light from being too harsh; in other situations, thick dark velvet curtain material blocks out sunlight entirely.

When shooting in video, certain colors or patterns can result in unwanted visuals; they require either careful lighting, or avoiding entirely:

![]() Stripes. A striped shirt, for example, can create a wavy effect on the video, known as a moiré pattern.

Stripes. A striped shirt, for example, can create a wavy effect on the video, known as a moiré pattern.

![]() Red. Certain bright shades of red can “bleed” and morph into other objects nearby.

Red. Certain bright shades of red can “bleed” and morph into other objects nearby.

![]() White. Too much white can overpower a scene and “blow it out.”

White. Too much white can overpower a scene and “blow it out.”

![]() Blues and greens. Some shades can blend together and become invisible. Don't dress your on-camera talent in blue, green, or silver if you're using blue, green, or silver screens in the background for any special effects you may be considering.

Blues and greens. Some shades can blend together and become invisible. Don't dress your on-camera talent in blue, green, or silver if you're using blue, green, or silver screens in the background for any special effects you may be considering.

V. THE AUDIO

The power of sound has always been greater than the power of sense.

Joseph Conrad

Sound design is a highly creative art, and the nuance of sound has a profound, if often unconscious, effect on an audience. The careful recording of audio during production, as well as clever mixing in postproduction, can make a visceral impact on the project. What a viewer hears has a definitive influence on what he or she sees. Sound design is a genuine collaboration between the audio recorded on a location and the extra layers of sound that are added and enhanced in postproduction.

We shot a scene in which a young couple was directed to have a romantic intimate conversation while slow-dancing in a crowded night club. There were another 20 couples on the floor, and a five-piece band on the stage behind them all. This was a highly controlled set—we wanted to record only the couple's dialogue. We asked everyone else to be totally silent, only mouthing a conversation. The band made the motions but didn't play a note. The other sounds— the other dancers’ conversations, shuffling feet and body movements, the tone of the room, the music the band was playing— would be recorded separately and added in later, during postproduction. We recorded the couple's dialogue by using a boom and two wireless lavs. But if even these were too muffled or unclear, we had the option of rerecording their conversation later. Then, in the audio studio, we mixed all these layers of sound together. The final result was a seamless integration of dialogue, ambience, music, effects, and acoustics. Voila!

![]()

Sound Design

An overall choreography of recorded sounds is known as sound design and usually includes:

![]() Dialogue. Conversation between the main characters in a scene

Dialogue. Conversation between the main characters in a scene

![]() Background or ambience. Muted conversations of extras in the background, barking dogs, sirens, playing children

Background or ambience. Muted conversations of extras in the background, barking dogs, sirens, playing children

![]() Sound effects. Narrative information, like a ringing phone or an angry shout

Sound effects. Narrative information, like a ringing phone or an angry shout

![]() Added audio. More thematic information, like a musical theme or a “sting”

Added audio. More thematic information, like a musical theme or a “sting”

If you could draw an audio storyboard, you would “see” audio everywhere: the dialogue, conversations in the room, the clatter of plates, and the tip tap of walking shoes, as well as outside noises like background traffic, singing birds, children playing, sirens, a parade, and planes flying overhead. These all combine to form an essential layer of ambience that complements the visual images. However, these extraneous noises can also be a major interference if they're not what you want to hear.

In most cases, bad audio is a sure sign of amateurism or sheer negligence. For example, a camera microphone, or mic, is limited, seldom sensitive enough to accurately capture the sound or to cover all sound emergencies. You'll want your camera to accommodate an external mic, one that the audio engineer attaches. And before each shoot, test the sound from all mics. When you're shooting sync sound—which is most of the time—consult with your audio engineer about the benefits of using a mixer board.

The Four Major Elements in Audio

In recording the audio, the audio engineer takes four major elements into consideration:

![]() The microphone (or mic)

The microphone (or mic)

![]() Acoustics of the location

Acoustics of the location

![]() Audio recording formats

Audio recording formats

![]() The perspective of the audio

The perspective of the audio

Microphones

Mics fall into these primary categories:

![]() Directional mic. Aimed directly at its subject. Captures only the subject's audio with as little other background sounds as possible. This mic is often a cardioid microphone (so named because of its heart shape) and records dialogue clearly.

Directional mic. Aimed directly at its subject. Captures only the subject's audio with as little other background sounds as possible. This mic is often a cardioid microphone (so named because of its heart shape) and records dialogue clearly.

![]() Shotgun mic. Mounted either directly on the camera, at the end of a boom (a long rigid pole that can extend as long as 18 feet), or mounted in a pistol-grip rig. It has a selective pick-up pattern that primarily records the sound in front of the mic. It can be as far as five feet away from the source of the sound and still get clean audio. A valuable add-on is a fuzzy windscreen around the mic that reduces most wind or breeze interferences.

Shotgun mic. Mounted either directly on the camera, at the end of a boom (a long rigid pole that can extend as long as 18 feet), or mounted in a pistol-grip rig. It has a selective pick-up pattern that primarily records the sound in front of the mic. It can be as far as five feet away from the source of the sound and still get clean audio. A valuable add-on is a fuzzy windscreen around the mic that reduces most wind or breeze interferences.

![]() Lavalier (lav). Clips onto a collar or tie, and picks up dialogue close to the speaker's mouth, isolating it from other audio. A lav also solves the problem of seeing a boom or its shadow in the frame. It can either be hard-wired and connected by cable to the camera or sound recording device, or it can be wireless and powered by a bodypack transmitter worn under clothing.

Lavalier (lav). Clips onto a collar or tie, and picks up dialogue close to the speaker's mouth, isolating it from other audio. A lav also solves the problem of seeing a boom or its shadow in the frame. It can either be hard-wired and connected by cable to the camera or sound recording device, or it can be wireless and powered by a bodypack transmitter worn under clothing.

![]() Omnidirectional mic. Sensitive to sound from any direction and source. It records dialogue and also captures all background sounds. This mic works best for recording man-on-the-street interviews and for dialogue where any ambient sound is required.

Omnidirectional mic. Sensitive to sound from any direction and source. It records dialogue and also captures all background sounds. This mic works best for recording man-on-the-street interviews and for dialogue where any ambient sound is required.

![]() Handheld mic. In interview situations, it's the most dependable mic because it requires sound pressure only from the person who's speaking into it. A hand-held mic can be either directional or omni, and can be hard-wired or wireless.

Handheld mic. In interview situations, it's the most dependable mic because it requires sound pressure only from the person who's speaking into it. A hand-held mic can be either directional or omni, and can be hard-wired or wireless.

![]() Prop mic. When it isn't feasible to use a boom or lav, the audio crew conceals a microphone in a prop or on set furniture to hide it from the camera. A mic can disappear inside a plant or a book that's close to the dialogue, be taped under a table, or draped inside a curtain.

Prop mic. When it isn't feasible to use a boom or lav, the audio crew conceals a microphone in a prop or on set furniture to hide it from the camera. A mic can disappear inside a plant or a book that's close to the dialogue, be taped under a table, or draped inside a curtain.

If there is any audio problem during a take, (i.e. barking dog, honking horn, or low flying plane), the soundman will wait until the take is finished and alert the producer as to the location and severity of the problem. The producer can then decide whether a retake is necessary.

Richard Henning, excerpt from interview in Chapter 11

The Acoustics of the Location

Audio engineers describe what they hear in very visual terms. One sound can be warm, bright, and round; another is hard or soft, fat or thin. The quality of the recorded sound is controlled to a great extent by the microphones used to capture them. Another important factor of recording sound is the acoustical setup of the location.

Sound waves are like fluid impressions. They can be muffled by surfaces that are soft and spongy such as rugs, furniture, clothing, curtains, and even human bodies. Sound bouncing and deflecting off surfaces that are hard and reflective, like glass, tile or vinyl floors, mirrors, and low ceilings, creates echoes or distortion.

Some locations can pose a real challenge to an audio engineer. A location might look just great, but it's got challenging audio problems—humming air conditioners, the buzz of fluorescent ceiling lights, ticking clocks, outside traffic sounds. As the producer, you may choose the controlled environment of a sound stage or studio, avoiding unwanted noises. Or, you may want a buzzing, busy background ambience.

Audio Recording Formats

In shooting most video formats, the audio goes through a single system. Here, sound is recorded directly onto the videotape, memory card, hard drive, or other storage mechanism. In the case of a multicamera shoot, the audio from each camera usually is fed directly to a videotape recorder (VTR). The audio engineer monitors the levels and sound from each microphone onto separate channels for mixing later in postproduction.

In a sit-down interview situation, when only the talent is being recorded, the best and safest sound comes from using two separate mics—a clip-on lavalier, and a directional mic mounted on a boom pole and stand— pointing from above towards the talent. If both the interviewer and interviewee are to be recorded, then a lavalier is clipped onto each of them and the sound, unmixed, is sent to two different channels. Once an audio level is set, and the camera rolls, a slight level adjustment might be made, but abrupt or constant adjusting is not only unnecessary, it's an editor's nightmare. The soundman then stays attentive and focused on what's coming through the headset.

Richard Henning, excerpt from Chapter 11

Because you want professional, broadcast-quality sound, most videotape formats come with four separate audio tracks or channels. It is possible to assign microphones to each channel. Now you've got the capacity for stereo recording, with two channels on the left and two on the right. These channels can be expanded later in the audio mix. HDTV broadcasting features the additional capability for 5.1 surround sound, a standard feature on DVDs and digital television sets. HD camcorder systems can record audio directly onto HD videotape with at least two tracks of audio.

The Audio Perspective

In the same way that an image is shot from a visual perspective, dialogue and ambient sound is recorded with an audio perspective in mind. For example, dialogue spoken by an actor in a close-up shot sounds clear, intimate, and appears to be coming from the immediate foreground. Dialogue yelled from across a busy street in a wide shot has a different perspective, coming from the background of the shot, as the distance blends in with the ambient sounds from traffic and other street noise.

It's not always possible to record sound that has the same perspective as the footage. A visual might be a very long shot, say, of two mountain climbers as they reach the summit. The only way to record their dialogue is by using a concealed wireless mic, but doing this could result in audio that sounds perfect for a close-up, though not for a long shot. It can be enhanced during postproduction with added sounds like blowing wind and crunching snow.

Recording Production Sound

Audio that is recorded during production on a sound stage or at a location is known as production sound and refers to all scripted dialogue, ambient sound, and background noise. If an unwanted sound creeps in, or the dialogue changes after the footage has been shot, most production sound can be rerecorded later in the postproduction stage. This is explored in greater detail in Chapter 9.

Portable Recording

Sometimes in addition to recording audio onto videotape with sync sound, you may also need to record audio independently—a voice-over, ambient sound like traffic or conversation, music from a performance—and mix it with other audio elements in post-production. Professional digital formats for portably recording isolated audio continue to be improved, though currently, each must be researched carefully to make sure it's compatible with both the video equipment and the editing system you're using.

Digital Recording

Today's most popular digital audio recording formats are MP3 24-bit recorders that record onto Secure Digital (SD) cards, and can import and export via USB ports into the computer. The device has both a built-in mic and can accommodate an external mic as well. It's able to monitor the audio levels, and has a time code reference.

In shooting digitally, the audio engineer cautiously monitors any digital distortion caused by audio that may be recorded too hot on the meter, because it's generally unfixable and useless. Loud sounds or high-pitched dialogue can peak the meter in the camera or in the digital recording device, so whenever possible she tests the audio before the shoot and won't allow the meter setting to go over zero. She usually sets the audio at −12 dB and even −20 dB, and is careful never to let the audio levels hit the top of the meter. She also listens to the camera's audio over the headsets before the actual shoot starts, and wears them throughout the shoot.

The Challenges of Recording Sound

Whether you're recording audio on a soundproof set or outside on location, there are situations to be aware of, and that you should try either to prevent or avoid altogether:

![]() Obstructions. Jewelry or clothing can rub or click against a clip-on lav.

Obstructions. Jewelry or clothing can rub or click against a clip-on lav.

![]() Boom pole. Boom poles vary in length (from a few feet to 18′) and in structure. They need to reach long but be lightweight so the boom operator doesn't tire out. Often the actual handling noise of the pole itself can create audio interference.

Boom pole. Boom poles vary in length (from a few feet to 18′) and in structure. They need to reach long but be lightweight so the boom operator doesn't tire out. Often the actual handling noise of the pole itself can create audio interference.

![]() Lights. Neon or fluorescent lights that are barely audible to the ear can cause a noticeable buzz on the audio track.

Lights. Neon or fluorescent lights that are barely audible to the ear can cause a noticeable buzz on the audio track.

![]() Appliances. Certain set pieces or existing appliances on location create their own sounds like a refrigerator, radiators, or an air conditioner.

Appliances. Certain set pieces or existing appliances on location create their own sounds like a refrigerator, radiators, or an air conditioner.

![]() Motors. Your location might be near a busy street or under an air traffic pattern.

Motors. Your location might be near a busy street or under an air traffic pattern.

![]() Weather. Thunder, the rustling of wind, even a faint breeze can be a detriment in recording clean dialogue.

Weather. Thunder, the rustling of wind, even a faint breeze can be a detriment in recording clean dialogue.

![]() Neighbors. A school playground, a lumber yard, an auto repair shop, or a house with a lawnmower can create interfering noises.

Neighbors. A school playground, a lumber yard, an auto repair shop, or a house with a lawnmower can create interfering noises.

![]() Construction. Incessant reverberations from jack hammers or saws can travel into a location or a studio, even from a distance.

Construction. Incessant reverberations from jack hammers or saws can travel into a location or a studio, even from a distance.

![]() Nature. Barking dogs, crickets, cicadas, blue jays and robins—each can be nuisance, or exactly what you need to create an added dimension of reality.

Nature. Barking dogs, crickets, cicadas, blue jays and robins—each can be nuisance, or exactly what you need to create an added dimension of reality.

![]() Batteries. If the battery power on a mic's body pack goes out, you've lost your sound. Plan ahead with an adequate supply of charged batteries.

Batteries. If the battery power on a mic's body pack goes out, you've lost your sound. Plan ahead with an adequate supply of charged batteries.

Most of these problems can be avoided with foresight, thoughtful use of microphones, and sound mufflers like moving blankets and microphone windscreens. You don't want to depend on the postproduction audio mix to fix your audio problems, but that's where you can often resolve unavoidable audio dilemmas.

Some Sound Advice

Your ultimate objective is to record and mix your audio elements so seamlessly that when you listen to it with your eyes closed, you hear no audio cuts or changes in levels. Any audio transitions from one scene to another should be equally smooth.

Most every challenge in recording production sound has a solution, such as:

![]() Record sound effects and ambience separately. If two characters are walking and talking as they pass an outdoor café, sound is around them, everywhere: the clinking of glasses, passing conversations, church bells, and fluttering pigeons. Whenever possible, record each of these sounds separately. In the audio mix, each is blended with the dialogue to create an overall audio impression.

Record sound effects and ambience separately. If two characters are walking and talking as they pass an outdoor café, sound is around them, everywhere: the clinking of glasses, passing conversations, church bells, and fluttering pigeons. Whenever possible, record each of these sounds separately. In the audio mix, each is blended with the dialogue to create an overall audio impression.

![]() Record room tone. Room tone refers to the subtle, nearly inaudible sounds that are unique to each and every set or location. At either the beginning or end of each camera setup or at the completion of a scene, while the entire cast and crew and equipment is still on set, the audio crew asks for complete silence and records 60 seconds of the sound in the room. In the audio mix, this room tone can fill in gaps in the dialogue or effects.

Record room tone. Room tone refers to the subtle, nearly inaudible sounds that are unique to each and every set or location. At either the beginning or end of each camera setup or at the completion of a scene, while the entire cast and crew and equipment is still on set, the audio crew asks for complete silence and records 60 seconds of the sound in the room. In the audio mix, this room tone can fill in gaps in the dialogue or effects.

![]() Keep continuity. Just as a script supervisor maintains visual continuity in a shoot, there is a definite continuity in recording audio, too. The audio levels between actors in a scene, for example, need to be constant and unvarying in volume. Any background or ambient sound is measured for consistency of levels so they don't interfere with the dialogue. When a camera angle changes, its accompanying audio might also be different.

Keep continuity. Just as a script supervisor maintains visual continuity in a shoot, there is a definite continuity in recording audio, too. The audio levels between actors in a scene, for example, need to be constant and unvarying in volume. Any background or ambient sound is measured for consistency of levels so they don't interfere with the dialogue. When a camera angle changes, its accompanying audio might also be different.

![]() Rehearse and rerehearse. There is a real difference between setting up audio for one shot in which both actors are walking and talking on the street, and a shot on a set where they're sitting quietly on a couch. Carefully consider how you can record the audio that fits with the visual camera angles and perspectives for each scene.

Rehearse and rerehearse. There is a real difference between setting up audio for one shot in which both actors are walking and talking on the street, and a shot on a set where they're sitting quietly on a couch. Carefully consider how you can record the audio that fits with the visual camera angles and perspectives for each scene.

![]() Keep an audio log. One person on the audio production crew has the job of keeping track of what is recorded on a set or location, including dialogue, ambient sounds, and special effects. This audio log, or sound report, lists details that are pertinent to the audio mix in postproduction such as the tape number with time code numbers (in and out points), the scene number, and the take number with a short description of what's been recorded.

Keep an audio log. One person on the audio production crew has the job of keeping track of what is recorded on a set or location, including dialogue, ambient sounds, and special effects. This audio log, or sound report, lists details that are pertinent to the audio mix in postproduction such as the tape number with time code numbers (in and out points), the scene number, and the take number with a short description of what's been recorded.

![]() Keep your cool. A lot of details are involved in recording good clean sound. The best place to learn is on the job, so get familiar with the tools of the audio trade, and keep your focus. Troubleshooting comes with the territory, and so does keeping your cool, all the time.

Keep your cool. A lot of details are involved in recording good clean sound. The best place to learn is on the job, so get familiar with the tools of the audio trade, and keep your focus. Troubleshooting comes with the territory, and so does keeping your cool, all the time.

VI. THE ACTUAL SHOOT

A long-playing full shot is what always separates the men from the boys. Anybody can make movies with a pair of scissors and a two-inch lens.

Orson Welles

Before starting principal photography, the producer checks and double-checks all the legal documents. You'll have copies of signed deal memos with the crew, contracts with the talent, release forms from the extras, and final location agreements—everything's been negotiated and signed.

Following are the key elements in most all shoots.

Arrival of Cast and Crew

Based on their call times, crew members arrive on the set or location. Usually the production department arranges for the transportation department to gather equipment, vehicles, set pieces, and other production materials to be delivered and unloaded early in the shooting day. The actors and talent arrive for wardrobe, hair and makeup, and any time-consuming special effects. Everyone's call time is given to them the night before in the call sheet, or by a phone call, email, or text message from the production department, by either the production manager or the AD.

Wardrobe, Hair, and Makeup

Actors and talent (including minor parts, extras, background people, children, and animals) usually need hair, makeup, and/or wardrobe before they're ready to appear in their scene. They may require only a simple hair comb, minimal makeup, and little or no wardrobe. Or, makeup could involve complex blood or scar makeup, facial hair or wigs, or a complicated period wardrobe such as an historical outfit or costume. The wardrobe, hair, and makeup people stay close to the set for any last-minute extra touch-ups such as a hair combing, powdering a sweaty nose, or adjusting clothing.

Dressing the Set or Location

The art director and his crew dress, or prepare, the set or location for the shoot. This can include finishing touches on the set pieces, adding furnishings, props, or greenery, and moving pieces around to accommodate the action or movements of the characters.

Craft Services

The craft services crew have set up and are serving food at least a half hour before the overall call time, and assembled set up a table for coffee, tea, water, meals, and/ or snacks for the cast and crew that is close to the shoot. They also serve at least one healthy meal a day or every six hours, depending on contractual agreements and the budget. When you pay special attention to craft services, everyone is happier, more productive, energized, and usually grateful.

Blocking for the Camera

The producer, director, DP, and/or gaffer survey the set or location, review their storyboards, and map out the day's shoot. They plan the placement of the cameras, lights, and audio equipment in a process called blocking the scene. Any revisions are determined here—all last-minute changes can slow up production and stress out the crew.

IN THE TRENCHES…

No matter what size my production may be, everyone involved is human, and all humans need food and water on a regular basis. My projects are primarily low-budget but I always budget higher for craft services and catering. Keeping my cast and crew well-fed and hydrated could well be the most important form of thank you that I can give my people—besides a huge lump of cash. Water, good coffee, health teas and bars, fruit, full meals— this epicurean gesture buys you a lot of loyalty when the days get longer than you expected.

![]()

Blocking the Actors

Once the camera movements are decided, the scene is rehearsed for the cameras and lights. Often a stand-in takes the place of an actor in the blocking. Any places for the actors are marked on the floor with masking tape.

Lighting the Set

Properly and thoughtfully lighting a set or location takes time. Depending on the size of the crew, the DP and the gaffer set the lights, replace bulbs, try different scrims and gels, and find various angles that work best. If a stand-in doubles for an actor, the crew can experiment with the lights while the actual actor is in makeup or rehearsal.

Audio Setup

All microphones and recording devices are set up, tested, and rehearsed. The audio may need muffling with heavy sound blankets or acoustical equipment. Any mic cables are kept away from electrical cables or wires to prevent interference. If a separate sound mixer is used, it's kept in an area where the audio engineer can monitor the different levels of audio coming from each microphone and keep them all in balance. Any boom shots can be rehearsed with the camera operator so the boom or mic shadows won't enter the camera's frame.

Rehearsing the Actors

Whenever possible, the director or producer rehearses the actors on the set where they will be shooting. This on-set rehearsal gives the talent a chance to loosen up in the shooting environment, and get familiar with the script. Sometimes the rehearsal takes place in another area away from the set, which allows the actors to concentrate.

Rehearsing and Blocking the Extras

Any people in the background (called extras or atmosphere) must be rehearsed and blocked, just like the main actors. A member of the crew, usually the AD, works closely with the extras in rehearsing movements such as crossing the set from one side to the other, chatting and laughing at tables, or walking behind the action. The extras are directed not to look into or at the camera, and generally only pretend to talk or laugh; usually they're told to move their lips in complete silence. Their audio is recorded later and added into the final mix.

The Technical Run-Through

This final rehearsal checks for technical details of the action being shot. Camera angles, lights, audio mics, dolly moves, the placement of furniture or props—all these are essential steps in the choreography of production. If you're shooting on a location, cover anything that could be damaged with plastic tarps or moving blankets. Move valuable or breakable items, like plants, furniture, china, glassware, that are part of the location. Someone is assigned to take careful notes and photographs of each object in its original place so everything can be put back exactly where it was, after the shoot. Leave each location in better condition than when you started.

Security

On any location, there are items of major value that can tempt hit-and-run thieves. Even on busy sets with people everywhere, things get stolen all the time. Hire a security company, or assign crew members like PAs and interns, to keep a constant watch on whatever you don't want stolen or damaged. Insurance doesn't cover everything. When someone is assigned to be on “fire watch,” for example, they're responsible for intently watching the back of the truck(s), and allowing only authorized personnel to come and go.

This particular shoot was for a high-end commercial, and the trucks were overflowing with cameras and equipment, wardrobe and makeup, props, and locations, officious clients, nervous actors—a recipe for chaos. There were at least 60 people, in and out of the sound stage, along with one large equipment truck, parked right outside, for all the audio and video equipment. We had one PA assigned to sit in the cab of the truck and another PA covering the back. Time came to shoot and the DP called for a specific lens, but it couldn't be located. It seems that the entire case of lenses—worth $120,000—had totally disappeared from the truck. It turned out that the PA covering the back of the truck had taken a five-minute bathroom break, neglecting to lock the back of the truck with a heavy padlock that's standard issue on shoots with valuable equipment. He also forgot to tell the PA in the front of the truck. So, with one person actually sitting in the truck, thieves walked right in and nabbed the lens case. Because we were the employers of this negligent PA, the insurance policy refused to cover the theft. We were responsible for paying the tab for $120,000 worth of lenses. If we hadn't covered ourselves with an additional insurance policy, for rare happenings like this, we'd still be paying the money back.

![]()

Shooting Publicity Stills

Often, a still photographer is hired to take publicity photographs that can be important to a publicity campaign as well as for archiving the production. The photos can be taken during the technical rehearsal, or, if the photographer uses a camera with a silent shutter, during the shoot itself. A professional still photographer knows how to get great shots without being obtrusive.

Lights. Camera. Action!

All the equipment, the crew, and the talent are in place and ready. Now, it's time for the shoot. The director calls for action and the camera operator and the audio engineer both confirm by saying “up to speed,” or “speeding.” Then the scene or action can begin.

Slates. Some video and film productions use a slate, or a clapboard, which is held in front of the camera each time it rolls. Like a small chalkboard, relevant details are chalked on it: the project title, the names of the producer and director, what camera(s) is in use, the scene number, take number, and date. Other video productions might use a smart slate, which matches the camera's time code with the audio. However, because a professional video camera records the sound directly onto the videotape or digital storage, slates are a matter of personal preference, not necessity.

Takes. With few exceptions, a scene is shot several times before it feels right to the producer or director; each attempt is called a take. You might run into technical problems like poor lighting, a boom in the shot, a misread line, or a number of other challenges that might occur as part of the production process. Additional takes can cover these problems up, so often a seasoned producer may call for a final take for safety, as a contingency.

Each shot in each scene has been planned out with its own camera and lighting angle and often its own lens. Each shot is assigned a description and a specific number on the shot list and production schedule. For example, the close-up of the small child digging in the sandbox might be the third shot in Scene #3. Every time the scene is shot—from “action” to “cut”—it is given a new take number.

Shot coverage. Every shot requires a new setup, usually with new lighting and different camera angles. Whenever possible, get your most important key shots first. Then, as time permits, work down your shot list for any remaining shots you still need. Depending on the creative direction that you want from your project, the general rule of production suggests that you cover one or more of the following shots:

![]() Establishing shot. Also called a master shot, it establishes the scene and what's going on in it. It is a wider shot of the whole scene that shows its action, the actors’ movements, and their relationships to each other. The master shot can then be intercut with tighter angles, such as:

Establishing shot. Also called a master shot, it establishes the scene and what's going on in it. It is a wider shot of the whole scene that shows its action, the actors’ movements, and their relationships to each other. The master shot can then be intercut with tighter angles, such as:

![]() Close-up. A tight shot, usually of an actor's face or an object. It is revealing and intimate, and shows more crucial detail.

Close-up. A tight shot, usually of an actor's face or an object. It is revealing and intimate, and shows more crucial detail.

![]() Single. A shot of one actor, in close-up, medium shot, or wide shot. When editing from one single shot to another, pay attention to continuity of eye-line.

Single. A shot of one actor, in close-up, medium shot, or wide shot. When editing from one single shot to another, pay attention to continuity of eye-line.

![]() Two-shot. A scene with two actors in the frame. Three- and four-shots have three and four actors in the frame, respectively, and are useful for variation and cutaways.

Two-shot. A scene with two actors in the frame. Three- and four-shots have three and four actors in the frame, respectively, and are useful for variation and cutaways.

![]() Over-the-shoulder. The camera is placed just behind the shoulder of one person and focuses on the person she is facing. That person's face is in the frame along with a portion of the listener's shoulder. This shot brings the audience closer to the characters and varies the cutting.

Over-the-shoulder. The camera is placed just behind the shoulder of one person and focuses on the person she is facing. That person's face is in the frame along with a portion of the listener's shoulder. This shot brings the audience closer to the characters and varies the cutting.

![]() Insert. A shot, usually a close-up, that reveals an important and relevant detail in a scene.

Insert. A shot, usually a close-up, that reveals an important and relevant detail in a scene.

Video monitor. It is vital to have a video monitor on the set. Connected by cable to the camera(s), the monitor shows the DP, director, producer, and other technicians what the camera sees as it's being shot. This can be especially important when shooting HD. The camera operator might not see something on the camera's small viewfinder, but can catch it on the larger monitor. It's also an instant playback of what was just shot. The monitor is the centerpiece of the “video village” where one or more monitors are set up for the producer, director, and DP (and often the client or investor) to view the footage as it's being taped as well as to watch playback between scenes.