Chapter 2. Why Is Product Leadership So Relevant?

The Product Leader’s Impact

A product leader is ultimately responsible for the success or failure of a product and, by extension, the company itself. The impact of that cannot be underestimated. According to Ken Norton, product leaders are “the implementers of the company vision,” always pushing the company forward by “focusing on what is most important to the company—what do we want to accomplish as a business and what do we need to do to get there?” Norton’s time at GV (previously Google Ventures) convinced him of the importance of product leadership. He believes that product leaders should have a vision for the product and where it should be in a year, in 5 years, and in 10 years—and then articulate this vision to the rest of the leadership team and to the wider organization. Creating a product vision and crafting a plan to get there is as relevant as you can get to the organization’s success.

As Ben Horowitz of the successful venture capital firm Andreessen-Horowitz put it 15 years ago while he was a Product Manager at Netscape: “A good product manager acts like and is viewed as CEO of the product. Good product managers have a realistic vision of what success of their product means, and they ensure that this vision becomes reality—whatever it takes. Good product managers are viewed by the entire product team as the leader of the product.” As we’ve acknowledged, the CEO analogy is problematic, but successful product leaders often look and sound like CEOs. Understanding that product managers are leaders and not just managers is the cornerstone of this book. Forgive us if we repeat this point throughout the book. It’s an idea worth reinforcing.

The Evolving Organization

The product team is in the unique position of trying to achieve an outsize impact, while having almost no authority over the teams that build, market, support, and sell the product. “When you’re a product manager,” says Norton, “you’re generally not the boss. You need to gain authority through your actions and your leadership skills, not your role.” This is very different from previous generations, when the manager held authority over the team and decisions by virtue of the title. That era has passed and a new approach to management has emerged. As Norton says, management is now earned through positive behavior.

Product leaders should never assume that their title qualifies them to lead by the inferred authority of the role alone. “Responsible and accountable does mean that we have teams that are actually accountable and responsible, and my job is to make sure they want to turn up to work,” says Nilan Peiris, VP of Product and Growth at TransferWise. “They work as one on a team, and that’s due to upfront thinking about hiring and about culture and about leadership within teams.” This cooperation doesn’t happen by accident. Product managers and leaders are expected to take an active role in building culture and leading their teams through the mundane day-to-day activities, not just the high-level strategies and vision.

Viewing product teams as peers to the other departments “sets up a healthy tension between engineering, product, and marketing, and the different ways those departments think. This is healthy because it allows product management to synthesize all these alternative views into the optimum decision for the product and the company,” continues Norton. Balancing the feedback and friction that comes from other teams and external sources is part of the job. An evolving organization realizes that eliminating friction isn’t the mandate—it’s understanding what insights might result from that friction. Maintaining this friction while preventing chaos is something Steve Selzer speaks passionately about. As the Experience Design Manager at Airbnb, he is referring specifically to the friction that results from a poorly designed UX, but his insights are relevant to all aspects of product. “It’s generally a good thing to remove friction, but we need to retain the friction that helps us grow, that helps us navigate change and become resilient,” Selzer says. As is the case with so many things in product creation, the rules that apply to successful product design also apply to successful product team leadership.

The Team

Without a team, the role of the product leader would not exist. The successful leader is reflected in the success of their team; and likewise, a poor leader is revealed by the failures of their team. It has been suggested that if product leaders were paid by the effectiveness of their teams, we’d have more successful products. How the team is recruited, developed, and guided is probably one of the most important elements of the product leader’s role. It is also, without a doubt, the hardest part of the job. “Every team deals with personalities,” says David Cancel, CEO and cofounder of Drift. “Sales and marketing have a certain set of personalities they deal with from a leadership standpoint. But product is very different and very interesting. For one thing, we’re in a market where product managers, engineers, and designers have all the options in the world, so why should they work on your product versus others?” Cancel, who has led product teams at Performable and HubSpot and was CTO of Compete (acquired by WPP), has an unconventional view on product leadership, “that may not be the same in other teams, where leadership can be very top-down and very by the book.”

Product leaders have more relevance because they are increasingly the people responsible for connecting the dots between the executive vision and the practical work on the ground. Bryan Dunn, Senior Director of Product Management at Localytics, talks about the early days at his company. “When the company was still small enough, our CEO and COO were making a lot of the product decisions, but as the company grew this didn’t scale very well. They would make some decisions but couldn’t get into the details enough to understand all the nuances and tradeoffs of those decisions. They might’ve seen the potential value, but in terms of feasibility and usability, they didn’t have enough depth or time to work through these things with customers in order to give the engineering team guidance about what the market needed.”

A product leader needs to balance the triumvirate of viability, feasibility, and usability. To do this, they look to the executive to handle the viability aspect and then translate that into what’s feasible and usable. The CEO should be setting the general direction for the company. For some early-stage companies, the CEO will also be occupied with raising money, adding senior team members, and a dozen other things. As Dunn says, “I was spending so much time with customers doing the detail-oriented work that a product manager does, that I started to have my own opinions about what we should be building.” Dunn’s observation shows that it is often the people closest to the customer who are best suited to make product decisions. This fact means that product leaders are also best suited to shape the direction of the product. Product leaders have firsthand insight into the customer experience. This insight might not be available or top of mind with all senior executives in the organization. The product leader must have the authority to lead the organization’s product direction.

The Makers

Managing the flow of information and directing the organization as an advocate of the customer are important aspects of being a product manager. Leading the internal team is an essential part of the job. “In product teams, you have to deal with makers,” says Cancel. “Makers are different, sometimes difficult or weird. In a product team we are all makers, and so the personality challenges that you deal with—how you build a team, how you align personalities within that team, and then how you motivate them—are very different.” Makers need uninterrupted time to create stuff and solve problems. Some process ceremonies can interfere with this focused time. All managers and leaders should be judged by their team’s outputs, and product leaders are no different. If you’re managing a team of makers, your day will be judged by how well you protected them from distractions and what they were able to make. This dimension further distinguishes product leaders from old-school management. No longer are they barking orders at subordinates; rather, they’re empathetically motivating creative personalities toward mutually rewarding goals. They create safe mental and physical places for makers and problem solvers to work, and make the team the heroes. This means the leader is also an advocate, coach, guide, mentor, and cheerleader to the team. As one executive product leader told us, “When I was a Senior Engineering Manager, my job was all about technology and process; now I’m Chief Product Officer, and my job is all about dealing with people and their emotions.”

Challenges Specific to Product Leadership: More Than Just a Seat at the Table

Product management and product leadership are not new roles. They are definitely better understood and more visible than ever before, but they have been around for some time. We and many of our interviewees have been marketing, designing, and developing internet and web products since the late 1990s. Even then, product managers and product leaders were taking care of business. What’s improved is how the role has been integrated into the overall business conversation. In the past, product managers were often line managers or functional leaders. We’re delighted that the current market expects to see those product leaders alongside the most senior people in the product organization. New titles and new visibility doesn’t always mean new responsibilities. Product still has to be shipped. However, getting a seat at the table has given product leaders the visibility they need to express their priorities. The challenges may be similar, but now they’re getting the attention they need to be dealt with appropriately.

In our conversations with product leaders we’ve heard that although they are clear about their value and role, it’s not always that obvious to others in the business. In the worst-case scenario, product leaders are often confused with more traditional senior roles like designers, experience designers, developers, engineers, or marketers, and this is understandable. One thing that contributes to this confusion is that product leaders often wear several hats. This is particularly true of smaller companies and startups. In these young organizations a product leader might join as a lead UX designer, but go on to manage the full spectrum of product deliverables. We’re not advocating that product managers be forced to do several jobs, but it does happen. Related to this is that often great team leaders—not just great product leaders—jump in where needed. The best leaders have a ubiquitous and positive influence in their organizations, and this can make it seem as if the product manager or leader is all over the place. The reality is that they are doing what it takes to ship product and make it successful, and if you see a product leader doing this, it’s because they care.

“For other leadership roles, you’re responsible for bringing a particular perspective to the table: [the] best possible way we can do marketing, [the] best possible architectural decision, or [the] best option for our service team,” says Ellen Chisa, VP of Product at Lola. “From the product perspective, you can’t just say this would be the best thing for the product, because that’s about putting all of those pieces together. It’s a role where you synthesize and figure out with each of those leaders’ expertise how you can make the most effective strategy.”

What Product Leadership Is Not

A product leader is not the source of all the answers. In such a dynamic environment it’s simply not possible to have all the answers. Product organizations are incredibly complicated places, and no single person can have every solution at their fingertips. Product leaders cannot memorize all the technical details of their job, and trying to would be a waste of time. Instead, a productive use of time is figuring out what the right questions are and where to get the answers to those questions. A culture where it’s OK for anyone on the team to say, “I don’t know, but I can find out,” nurtures responsibility and maturity, and is a far better strategy than pretending to be a human search engine.

What Makes Product Leadership Strategic

Product leadership “has a lot in common with all types of leadership roles, which is simply that your day-to-day work becomes less important than how you actually lead a team to accomplish something,” says Mina Radhakrishnan, the first Head of Product at Uber, who is now a mentor at 500 Startups while working on a new startup. That difference between how much you do and how much you enable others to do is a common factor across all leadership roles, whether it’s product leadership, marketing leadership, or engineering leadership. “The difference with product leadership is that it becomes especially important to focus on strategy and to really think about how all of the different elements come together with the overall company strategy. Essentially the product strategy is the company strategy,” she adds. Ultimately a product leader is responsible for the product strategy but can’t build anything by themselves and must lead engineering, marketing, design, and other teams under the umbrella of the company strategy, all without the aforementioned authority.

What Keeps Product Leaders Awake at Night

In a recent survey, Mind the Product1 and Christian Bonilla, Product Manager and founder of UserMuse, asked product managers and leaders what challenges they faced. The results indicated that prioritizing roadmapping decisions without market research was by far the biggest, followed by being stretched too thin, dealing with executives, hiring and developing talent, and aligning strategy.

Prioritizing Ideas, Features, and Projects

It’s not surprising that prioritizing ideas or features rates high among the challenges faced by product leaders. Any product manager knows that the most difficult part of their job is determining what to spend time, money, and energy on. This is because it’s a deeply charged topic. These are not just ideas or features; they are people’s pet projects, and a lot of emotion is tied to them.

In the Mind the Product survey, 49% of product managers said their foremost challenge is being able to conduct proper market research to validate whether the market truly needs what they’re building. When we look at the responses from enterprise software PMs, this figure jumps up to 62%. That means that almost two-thirds of enterprise product leaders are currently worrying about which projects are needed. If we extrapolate from this, an enterprise product leader will have to dedicate the necessary amount of their time to prioritizing projects and communicating to others the next product release. That’s a lot of tough conversations with a lot of unhappy people. Having to make tough decisions that might disappoint people sounds stressful, and it is.

And that’s not all. In any organization, small or large, stakeholders also need to be dealt with. Often in senior positions, these people will impose their choices or opinions without the necessary data or understanding, a situation commonly known by the derogatory nickname HiPPO, for highest paid person’s opinion. As common as this term is, though, it doesn’t really give these unfortunate situations the context they deserve. Senior people are rarely malicious, and referring to them as thoughtless animals only reinforces the stereotype.

The reality is that stakeholders clouding decisions without evidence can derail even the most well-thought-out plans. Nobody likes it when high-level ideas are added to the roadmap as must-haves, especially when they are not backed up with validation. “The team just experienced another executive swoop and poop,” says Jared Spool, founder of User Interface Engineering2 and cofounder of CenterCentre, likening these executive decisions to a seagull attack. “The executive swoops into the project and poops all over the team’s design, flying away as fast as they came, leaving carnage and rubble in their wake.” As humorous as this sounds, it’s also Spool’s hyperbole. Teams and their leaders are more often working toward common goals and have no desire for anything ending in carnage and rubble. The absence of evidence is addressable without drama.

To many product professionals, having their roadmap hijacked from time to time by other pressing issues is an unavoidable situation that must be tolerated. Tom Greever, author of O’Reilly’s Articulating Design Decisions, calls these hijacking decisions the CEO button, “an unusual or otherwise unexpected request from an executive to add a feature that completely destroys the balance of a project and undermines the very purpose of a designer’s existence.” We acknowledge that these interruptions can often be harmless, but if they continue unchecked, they will ultimately derail the product. Fortunately there is a solution, but it is not a quick fix.

Prioritization can be polarizing because it’s often perceived as choosing one person’s ideas over another’s. When people have something personal invested in an idea or feature that’s on the chopping block, emotions can run high. The solution is collaborating at several levels. It is the product leader’s job to connect with all the stakeholders and communicate to each of them why certain choices have to be made. It starts with developing a shared vision and purpose for the product. If the team doesn’t agree on the big picture, then they certainly won’t agree on a single feature.

“As product managers it’s our job to make sure that the company is building the right product, but many (possibly a majority) of us don’t feel like we’re doing that,” says UserMuse’s Christian Bonilla. “Nearly all of the responses in this [prioritization] bucket expressed not having time to do market validation at all.” Bonilla reminds us all that it’s easy to get stuck on the treadmill and forget what the most valuable things are for product success. “It’s a little sobering when you think about how much time, money, and energy is being wasted building features that the market doesn’t want or need. It also tells me that the career development of many product leaders is slower than it ought to be.”3 This point highlights the importance of why product leaders need to be learning the art and science of prioritization.

Mina Radhakrishnan adds, “A big part of product leadership is thinking about why are we doing this and using that to set the basis for saying, ‘No, we shouldn’t do that. It doesn’t make sense in the context of our larger strategy at this time.’ I think that’s really critical.”

One way to avoid future disappointment is to create a testable prototype of the idea, feature, or interaction that is being planned. This can be done for most design features and interactions, and currently, the easiest way to do this is with the design sprint or Directed Discovery. Both of these approaches are based on the scientific method of developing a testable hypothesis and then running the appropriate testing cycles to generate results, providing immediate evidence either for or against the hypothesis. “When the team invites real users to try a prototype, they’re collecting data about the users’ needs, which provides a solid footing for the design,” says Jared Spool about design sprints. “When the executive shows up, the team can present the data along with the design that emerged from it. Demonstrating the data behind the design decisions reduces the potential for negative influence the executive can assert, and smart executives will embrace the approach.”

Collaborating Effectively and Productively

Collaborating is the way to get there, but it’s the outcome of this collaboration that’s the key insight. “Remember that collaboration is not consensus. Not everyone has to agree all the time. In fact, consensus rarely happens,” says C. Todd Lombardo, Chief Design Strategist at Fresh Tilled Soil and coauthor of the book Design Sprint (O’Reilly). “The roadmap prioritization approach is co-creation at its finest, which is akin to the Ikea effect: we love our Ikea furniture because we built it ourselves. The same applies here with product roadmapping. Involve the whole team and avoid sending off that Excel file via email; otherwise, you’ll watch your email or Slack channel suddenly erupt in a fit of rage.”

Lombardo, who has led hundreds of product design sessions, believes that the way to get over the collaboration hurdle is to share the details of each person’s perspective and opinions in a structured and repeatable way. Within the design sprint or Directed Discovery approaches are dozens of discrete exercises that team leaders can use to create collaborative sessions (see Figure 2-1 and Figure 2-2). For example, if the CEO wants to include a feature, then the product leader gets additional details from the CEO about why that feature needs to be included. This information or reasoning gets mapped against all the other features and perspectives so the entire team can see who wants what, and why. An idea that has no data, evidence, or testing behind it will not hold up against an idea that has the weight of research or testing behind it. Voting and ranking exercises add visibility and expose weak perspectives. Exposed to such close scrutiny, these executive decisions may be easier to defeat. This is not guaranteed, though, and product leaders should be prepared for some tough negotiating. Lombardo reminds us that “work is personal, so address that head-on with your team by including them in your roadmapping process.”

Figure 2-1. Gilbert Lee (center, standing) working with the Pluralsight product management and user experience team. At Pluralsight each product team is cross-functional and collocated. Every week the team gathers for two hours and works on each other’s experiences to arrive at the best outcomes for each experience.

Figure 2-2. Matt Merrill of Pluralsight (standing, left) taking his turn to describe his team’s continuous discovery and delivery work. Success means understanding each team’s work and the dependencies that may lie ahead so all can work and collaborate together.

Product leaders should get trained in these disciplines and teach their teams how to conduct the collaborative sessions. Without these tools a product manager or leader can get stuck in a spiral of bad choices driven by executive will. “It’s a bonus when the executive partakes in the Design Sprint directly,” says Spool. “Not only do they see the rigor of the process, they can contribute their knowledge and experience firsthand.” The benefit of any structured product collaboration process is that it neutralizes the politics in the organization and allows more junior voices to be heard. A level playing field lets the best ideas stand out, which makes the prioritization process infinitely easier. As Spool explains, “through each phase, the facilitator leads the activities using techniques designed to empower each participant, regardless of role power. Ideas and contributions from the sprint team’s lowest-ranking member are equal to that of any executive or other high-ranking members.”

The insight for the leader is that using these process-driven solutions doesn’t exclude the need for leadership skills—specifically, leading with influence and relationship-building skills. Often, even after all that evidence and process work, the CEO still wants their request implemented. Tom Greever suggests that it’s not always about getting your way: “I would argue it has as much to do with earning trust and building a relationship with that CEO than it is convincing them they are wrong.”

Another key skill product leaders can bring to bear from their day jobs is using their user research experience to truly understand the CEO’s perspective and the reasoning behind the request. Understanding the why will help find common understanding and walk back to the real problem that needs solving.

Training and Developing the Product Team

Teams don’t become teams by themselves. You may have the smartest people money can buy, but if they can’t work together, then you might as well not have them at all. The trick to creating a great product team is to think of them as the product. This is not an objectification but rather a thought exercise. After all, they are the product that creates the product. Without them, there is no product. Amazing teams make amazing products. Seen from this perspective, the task of how to hire, onboard, train, and develop them becomes another product design problem. The approach that successful leaders take to creating great product is the same approach they take to creating great product teams.

The first step in product design is defining the purpose and the problem. In team creation, the principles of discovery and understanding apply too. Structured sessions where team members can discuss their biggest challenges and what they understand as the team’s purpose will highlight any gaps. A timeboxed tool like design sprint can be used as a guide through this training. The specific approach you use doesn’t matter too much, as long as you are guiding the team through a process of understanding the problem and finding the solution. Ideally, the outcome should determine what problem the team is trying to solve, and with this insight, you can devise strategies for how the team can implement solutions.

Getting the team on the same page is the underlying reason for this work and should not be rushed. Understanding the problems and the environment that’s contributing to them can take time. An hour on a Monday morning might not cut it, and some teams may need several sessions to come to an understanding of each other. Ongoing and consistent training should be built into the team’s weekly schedules. This might sound time-consuming, but it’ll save time and money in the long term if the team works productively and collaboratively toward a shared agenda.

Individual growth plans for leaders and their teams are as important as team training. Everyone needs to be challenged in positive ways in order to grow and learn. Unfortunately, individual growth plans rarely make it past the first meeting, and too often a well-designed growth plan ends up being ignored or forgotten. To combat this, short but frequent check-ins with team members, instead of quarterly or annual reviews, will keep the individual’s attention on their plan, while using their goals as a lens to focus activities. Reminding a team member of one of their OKRs (objectives and key results) has the same effect as removing distractions from their plate: it refocuses them on what’s really important. Quarterly and annual reviews are too spread out and will not have the impact required in fast-moving product teams.

Successful leaders don’t assume that hiring smart people is enough, just as they understand that using smart tools or processes is not enough. Without the right guidance and direction, neither great people nor perfect processes will produce good results. Ongoing, regular, and consistent training has the additional benefit of teaching teams the value of process—eating your own dog food, if you will (or as we prefer to say, drinking your own champagne).

In the sections that follow we will dive deeper into the various challenges facing different types of organizations. Startup teams are, and should be, very different from enterprise teams. However, the approach toward making these teams successful can be common to all. Focusing on a common problem that’s well articulated and then building a structure that reinforces that focus is the common thread in all team development. Keeping a clear connection between the bigger team goals and individual OKRs is a daily or weekly responsibility for product leaders that is well worth the time and effort.

Managing Upward and Outward

Being a product leader means being the middle of the sandwich, squashed between senior stakeholders (executives, investors, board members, etc.) and your product team (designers, developers, marketers, etc.). As if that’s not enough, they also have to deal with inputs from other departments, customers, partners, and occasionally, the media. Developing a holistic view of the product environment and understanding that the product doesn’t live in isolation will bring clarity. The work of leading product creation is not about technology—it’s about the ecosystem and, in the words of Vanessa Ferranto, Head of Product at Zipcar, “about understanding that the product isn’t just software or hardware, it is the entire experience and the community.” Leadership at any level is a community position. For product leaders this is even more the case given their pivotal role.

Managing the expectations of senior stakeholders isn’t simple, but it is possible. “In the first part of my career, I was really focused on putting myself in my customer’s shoes. Now, I’m trying to be just as conscious about stakeholders too,” reflects GrubHub Senior Product Manager Rose Grabowski on her increasing empathy for stakeholders. “Not just thinking about what drives them, but really, deeply thinking if I were them, what would I want? In this case, I’m thinking about the sales team, the engineers, the marketing people, all the internal stakeholders. I’m trying to really empathize about their concerns, and ensure I take those concerns into account at a deep level. I try to put myself in their shoes.”

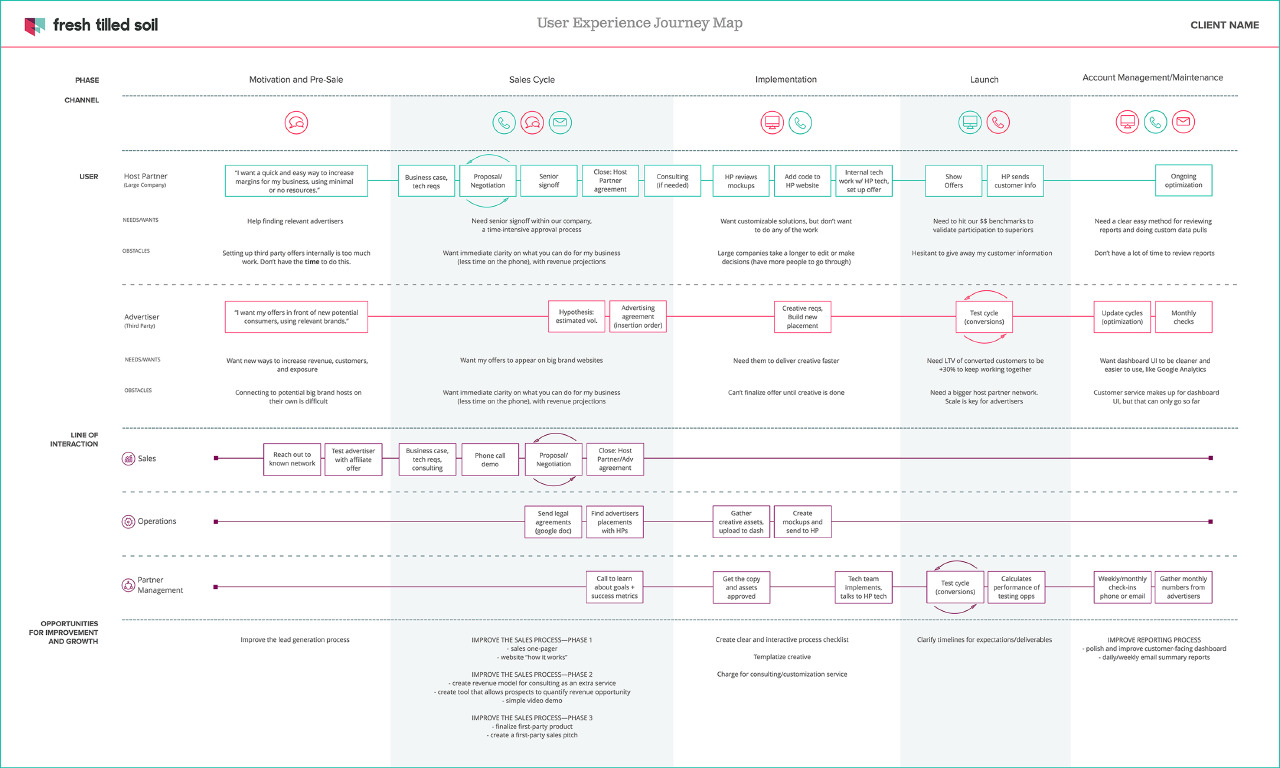

Once again, the product leader finds themselves dealing with people, their individual needs, and their unique personalities. Mapping the ecosystem of stakeholders using one of the persona exercises will give the leader the chance to visualize the people in their product ecosystem and assign qualities to them. Knowing who is a potential roadblock and who is a decision maker allows the leader to develop strategies to deal with those individuals. Going a step further and developing an experience map of the organization and its environment deepens the product leader’s insights. This might sound like a lot of extra work, but it offers useful benefits. Being able to identify obstacles and orchestrate solutions around those potential blockers can mean the difference between shipping and not shipping. Persona maps, who/do exercises, empathy maps, and experience maps (see Figure 2-3) need not be complex. A few hours constructing or sketching these realities will give the product leader the ammunition to deal with what might otherwise be a frustrating ambiguity.

Figure 2-3. Experience map (source: Fresh Tilled Soil).

Again, it is apparent how the tools we use for product creation are equally useful in the context of the product leader role. Employing the exercises available for successful product design and development to manage the team will give the product leader a significant advantage.

Aligning and Focusing the Organization

We’ve discussed the topic of aligning the organization toward a common vision several times in the context of hiring, team building, and managing other groups. It’s such an important topic that it’s worth a little more attention, however. The reason it is so important is that a common vision is the hub to which all activities and decisions are connected. It is the lens through which the organization finds its focal point, aligns the entire team’s energy and attention, and reminds them what isn’t important. Much like a set of values, a vision clarifies what’s going to be part of the organization’s future and what will be ignored. “The challenge is clearly communicating that vision to everybody on the team such that they understand how they are contributing to it,” says Jeff Veen of True Ventures. Humans do well in situations where there is a clear description of the future they are headed toward. This natural behavior translates to business and product visions. Aligning the team’s daily activities with that vision allows your team to connect the dots and see the path ahead more clearly. “If you can connect those dots for people, they’re gonna be so happy,” continues Veen. “There’s all kinds of other factors, but if they know the work they’re doing today is going to contribute to a vision they believe in, in a measurable way, man, that’s golden.”

A vision isn’t a poster on the office wall or a weekly newsletter to the team. It’s a concept of what the future will look like with the energy to back it up and something that should be regularly communicated to the team. Regular all-hands meetings and onboarding training are examples of how this can be communicated. A single viewing of the corporate video is not enough. The company vision should be mentioned or presented weekly if possible, and included in all team meetings and in all-hands meetings.

Mike Brown, Product Manager at PatientsLikeMe, underscores how critical a shared vision is: “In any product that you’re building it’s important to align all the different people in the system. It’s not just about creating an ideal experience from the UX side or about having the right structure of data from the research side or engineering side, and it’s not just about making money on the business development side. You really have to bring all of these things together. It’s often a diverse group of people who have different opinions about how things should work or what we should do to solve a certain problem. As a product person, if you don’t have a passion for the things you’re doing, it’s going to be really hard to rally a diverse group of very bright people around an idea to actually not only define what it is that you are going to be solving, but also how it will be executed.”

The importance of vision cannot be overstated. In the next chapter we’ll explore vision setting in detail.

1 Christian Bonilla, “The biggest challenge for product managers?” Mind the Product.

2 Check out the User Interface Engineering (UIE) home page.

3 This last comment is more of an opportunity than a problem in our minds. Product leaders are ready to develop new skills and new approaches. Developing the right skills for the appropriate part of your career is a deliberate and necessary part of dealing with the prioritization problem. It’s one of the reasons we wrote this book, and probably one of the reasons you’re reading it.