3 LIGHTING AND PRACTICE

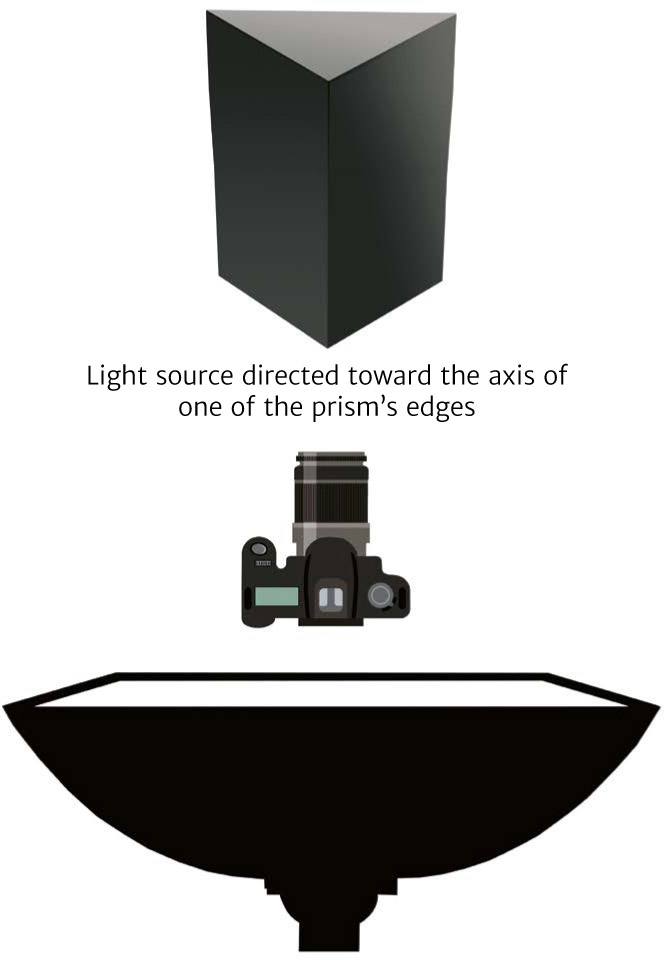

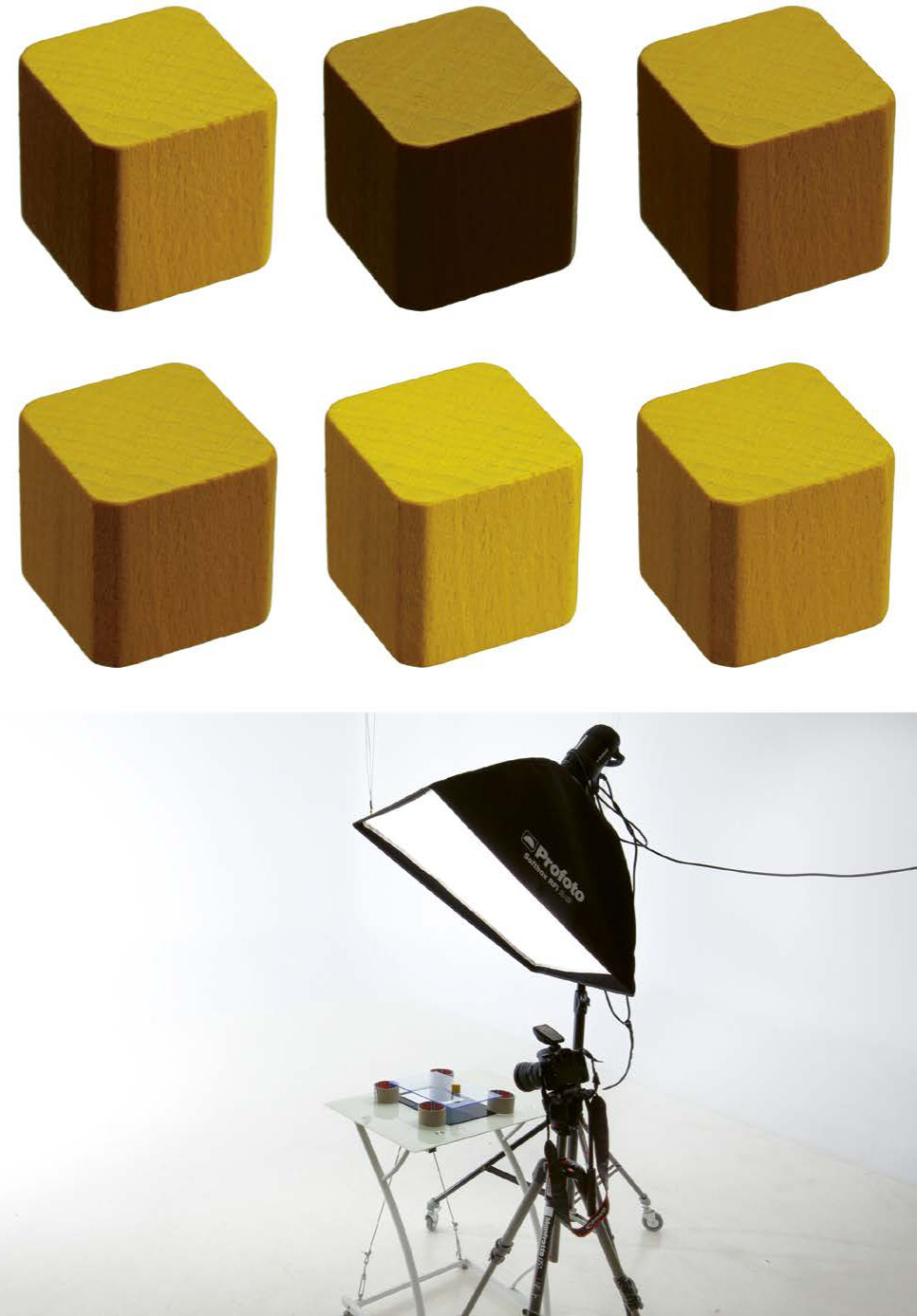

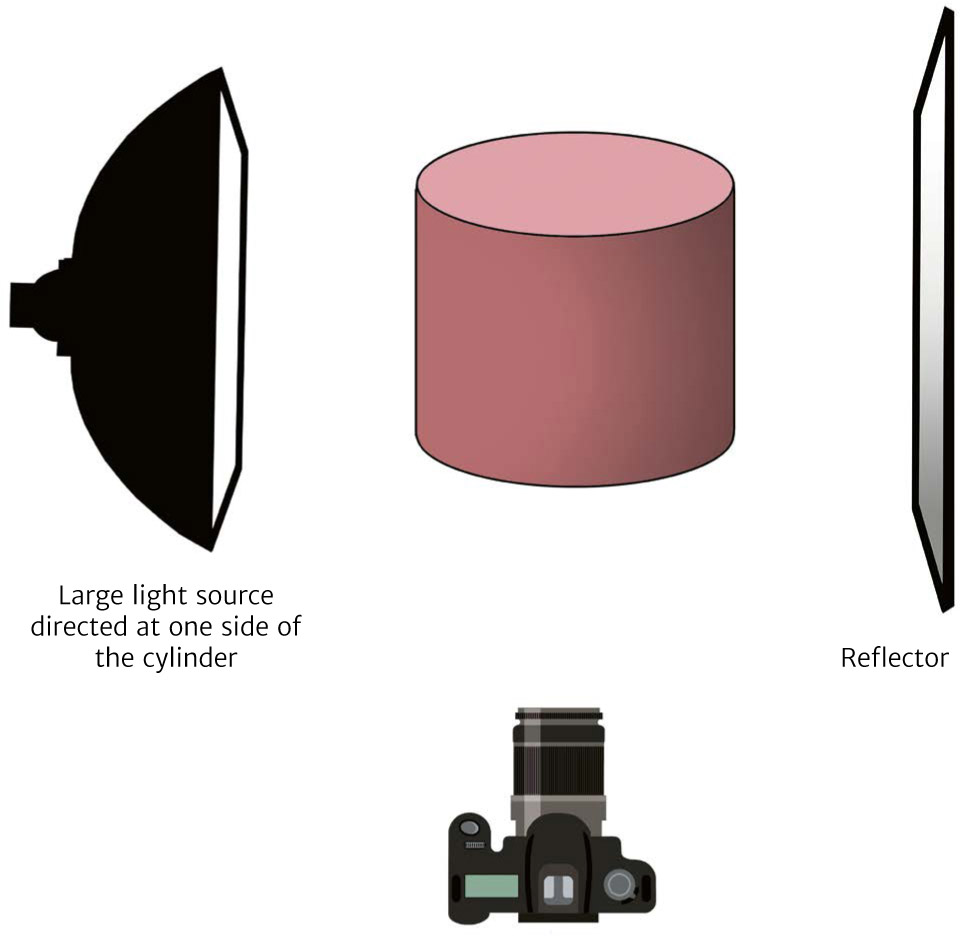

Bottles of Rosé and White Wine

Stores and websites that sell photographic equipment offer a wide range of useful accessories for product photography. But each tool has its own specific use, and they are not all suitable for all cases. One mistake many novice photographers make is to outfit themselves with a lot of accessories before they have really grasped what they are good for and how they work. In reality, every accessory has a very specific field of application, appropriate to one type of object and usually not very helpful for other kinds. The light tent, also known as a shooting !tent or diffusing cube, is a cube of white diffusing fabric, held in place by piano-wire frames (which allow the cube to be folded up between uses), and whose front side can be closed up. The camera lens is then placed through a small slit in the fabric to avoid frontal reflections. These come in a wide variety of sizes, ranging from ten inches to six feet wide. They generally come with fabrics in several different colors (typically white/gray/black, but some manufacturers offer other colors) that are placed against the background and underneath the object to be photographed. This makes it possible to light the object along several different axes while maintaining an even diffusion of the light. This setup is well suited to matte and/ or slightly satiny objects that produce diffuse reflections, as well as to cylinders. However, it is completely counterproductive if you’re lighting spherical objects that generate direct or specular reflections—because of its shape, its framing wires and interior seams are reflected in the glossy objects and are visible in the photo. EXAMPLE OF ARRANGEMENT OF LIGHT SOURCES FOR USE WITH A LIGHT TENT As with all diffusing fabrics, it is absolutely essential to perfectly smooth out all the sides of the cube ahead of time using a steamer; otherwise, its texture could appear in the reflections. Because most commercial diffusing fabrics are lightly plastic-coated, you can’t iron them. WORK STRATEGY For the lighting, we usually use four light sources: two on the side, one above the cube, and one in rim light (unless a fabric has been placed to appear in the background of the image). The front part of the cube is not specifically lit: the reflection of the light inside of it is sufficient for that. Even though the cube’s fabric diffuses the light, we place softboxes on each of the light sources so that we achieve consistent, even lighting. The light tent is perfectly suited to matte objects and to glossy cylinders, primarily polyhedrons: thus, it is the ideal tool for photographing soda cans, shoes, boxes, books, or untreated wooden toys. The diffusing dome is much like the !light tent, but it has the advantage of a rounded roof, which allows you to avoid any reflection of the interior seams for glossy objects that are rounded on their upper part. But it still won’t work for spherical objects. It is used similarly to the tent; it works well for polyhedrons and glossy cylinders and can also be used for objects with slightly rounded tops (with a family of angles that is less than 100°). The packaging shot table is more flexible !because it gives the photographer greater freedom of movement and allows for more lighting possibilities, but it also requires more equipment to operate effectively. TRADITIONAL PLACEMENT OF THE LIGHT SOURCES ON A PACKSHOT TABLE It is made out of a sheet of translucent, diffusing plexiglass (generally the Perspex brand) placed on an adjustable frame, where the angle of the background, in particular, can be manipulated. The table is generally equipped with wheels to allow it to be moved around, and with clamps to attach accessories (reflectors, diffusers, or barn doors) or light sources. The diffusing plexiglass allows for lighting from below, and the rounded cyclorama-shaped backdrop makes it possible to obtain a perfectly uniform background behind the object (as long as it is lit with direct light rather than backlighting, which would produce a shadow on the lower part of the background). Note, however, that the lighting from below must be very precisely measured so that the lower part of the object does not show highlights. You can also avoid problems by placing the object on a transparent plexiglass base. The final step is to set up your light sources around the object, being careful to diffuse them appropriately (see previous photo). The packaging shot table is suitable for objects of all shapes and surfaces. When the object is being photographed !from above, or from a bird’s-eye view, and the background does not appear in the photograph, a standard table can work fine. We shape the light by placing diffusers, barn doors, and reflectors in the appropriate places. This is the method I prefer for creating photographs of jewelry, watches, and glasses. For a few years now, manufacturers have !been offering cubes whose internal wall, equipped with a reflective fabric, has LED lighting. These have the same qualities as light tents, but with less lighting flexibility because the placement of the LEDs is fixed. A product photographer usually dresses in black or !dark gray. This may sound strange, but when you are photographing reflective objects, such as Christmas tree ornaments, your own reflection will often appear in the image; if you are dressed in dark colors, this is less problematic.TECHNICAL IMPLEMENTATION

The Light Tent

The Diffusing Dome

The Packshot Table

The Standard Table

LED Reflecting Cube

The Photographer’s Outfit

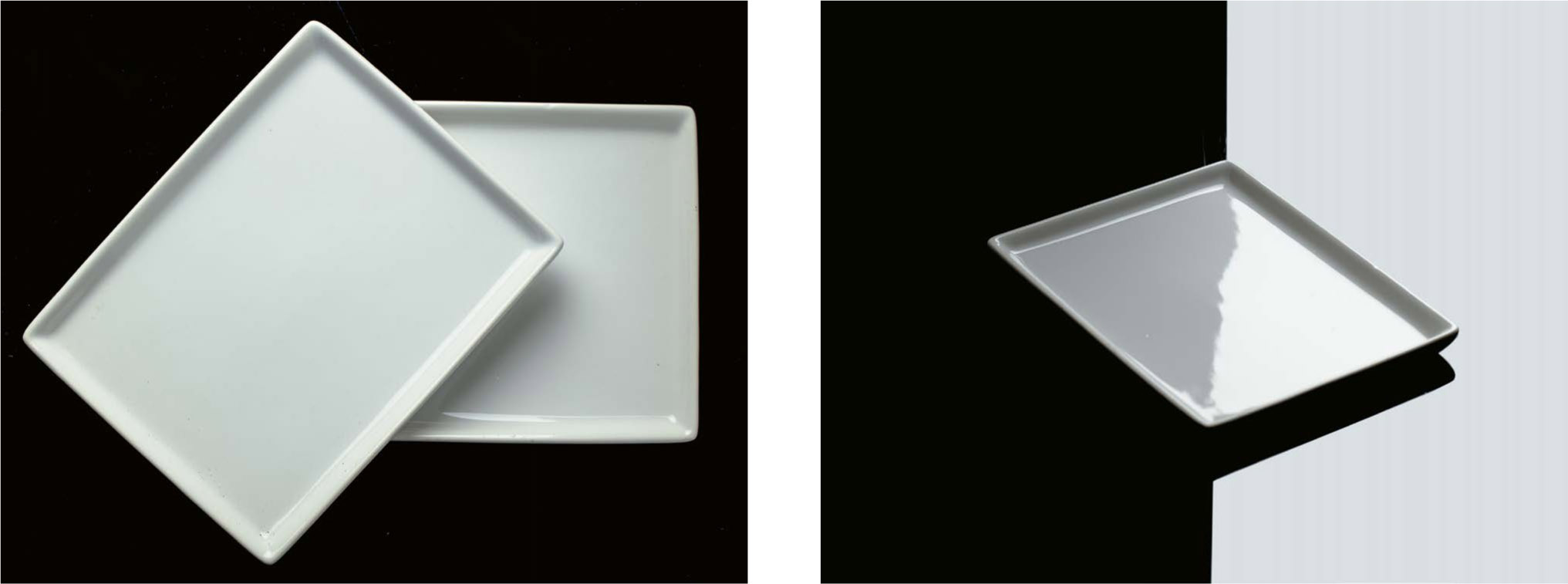

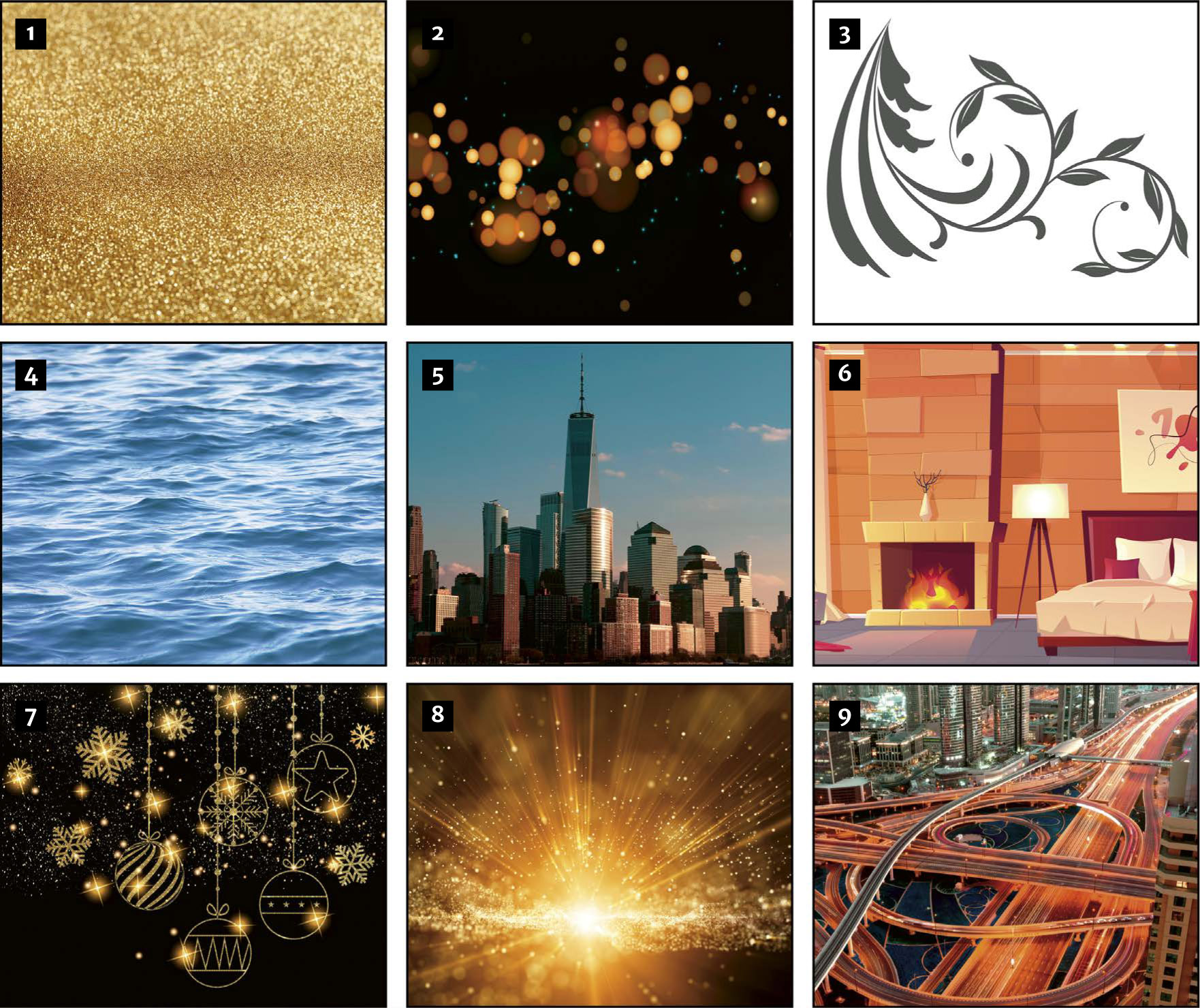

The studio of a photographer who specializes in packaging shots—with its profusion of panels, sheets, and materials used to showcase all kinds of objects—is a veritable treasure trove. With experience, it quickly becomes clear that the base on which the object is placed, and which will serve as a background, plays an important role in how the colors of the object end up looking and, overall, in the look of the photograph. With the exception of packaging shots for catalogs, which require a perfectly white background, you will have to think carefully about this issue. The surface on which we place the object to !be illuminated can play many roles, depending on the material out of which it is made, its optical qualities, and its color. Thus, aside from the effect that the background can have on the object, it is also necessary to think about its own intrinsic aesthetic qualities. It has to harmonize—in color, shape, mood, and texture—with the object being photographed. We wouldn’t use the same background to present Corsican figatelli sausages, a high-tech mobile phone, or a bottle of perfume: each of these objects belongs to a different aesthetic register, and so for each one we must determine the ideal context. Studio backgrounds, easy to use and perfectly matte, are made of thick high-quality paper, with a fine-toothed antireflective surface that allows you to obtain a uniform color. They are generally sold in rolls of 36 feet (the standard widths being 53 inches or 9 feet), and they are available in a multitude of colors. You can also choose cotton-fiber art papers (like those made by Canson), which have the same characteristics and also have the advantage of already being cut into dimensions that are appropriate for photographing objects. The idea is to choose thick sheets (> 150 gsm) to avoid running the risk of folds. You could theoretically work with all different colors of paper, depending on the scenario, but we most often end up choosing half-tones of black, gray, and beige, which work well in most situations. EXAMPLES OF BACKGROUNDS AND ACCESSORIES OFTEN USED IN PRODUCT PHOTOGRAPHY The reflection of the color of the paper being used as a background in this photograph ends up tinting the lower edge of each object being presented. Often used for their !nonreflective qualities, matte plastics are effective at avoiding reflections on objects while being easily washable (which is something we look for when we are working with fluids). The plastics are generally Trespa, HPL, or PVC, which can be found in hardware stores, home design stores, and kitchenware stores. Note that these backgrounds have a tendency to develop scratches and do not withstand heat very well, so you need to make sure to store them carefully and avoid impacts. Whether plexiglass, polycarbonate, Alupanel, PVC, or polyethylene, these backgrounds, once they have been lacquered, are very glossy and can occasionally serve as reflectors. They have the advantage of acting differently depending on their position in relation to the light source. Thus, a sheet of glossy black plexiglass placed within the family of angles transmits most of the light and appears white or light gray, depending on the luminous intensity—which is perfect for glassware: the background looks white but its reflection in the glass stays black, which provides well-defined silhouettes (see the photo above, right). And with glossy white plastic, we get the exact opposite effect: placed outside the family of angles, it will look completely black. This wineglass is positioned on a sheet of glossy black plexiglass that looks light gray because it is within the family of angles of the backlighting. A sheet of glass placed under the object makes it possible to both play with the reflection (as with glossy plastic) and separate the shadow from the object that produced it. The farther the shadow is from the object, the softer it becomes. This method is useful for obtaining photos without shadows, which is useful for photos that are meant to be cropped for use in catalogs, for instance. It also makes it possible to trick the viewer’s gaze, giving the impression that the object is suspended in air. And because glass is less susceptible to scratching than plastic, it is used much more often—whether transparent or translucent glass, or black smoked glass. Even though all the glossy materials mentioned so far act somewhat like mirrors, none of them are able to transmit all of the light they receive. When you want to make sure to get a perfect reflection of the object or light—in order to produce a perfectly white background or to reflect, for example, a computer screen—an actual mirror will be your best option. Mirrors can also be used as reflectors when the light is too weak and the reflectors can’t be brought any closer without appearing in the field of vision. Brushed cotton (or cotton flannel) is perfect for obscuring reflections and is therefore widely used in photography. It is generally black or white, but it also exists in a wide range of colors. As its name indicates, it is a cotton fabric whose very tight weave is machine-brushed, giving it a fuzzy appearance. Its irregular surface means there is no risk that it will cause a reflection. Brushed cotton is the ideal background material when you do not want to allow any reflections at the base at the base of an object, such as a crystal ball. It can also be used to make excellent barn doors. Perfume bottle suspended from a fishing line, half-submerged in the water of an aquarium. A black barn door is placed behind the aquarium, and two softboxes equipped with rust and cyan color gels are positioned in the backlight (see the staging arrangement above). Even though liquids are not, strictly speaking, backgrounds, there has been a custom of presenting objects in water, oil, or paint. These types of setups can be photographed from above, by placing the liquids in shallow containers, such as kitchen trays or terrariums, or through a glass, like the glass of an aquarium. Liquid is only interesting as a background when it is in motion, usually with undulations on the surface (we use the kind of electric blower that is used to clean computers, or a compressed-air spray bottle), or if the object itself is in motion (see photo opposite)—but the liquid must be partially within the family of angles of the lighting so that the different undulations on its surface can be clearly distinguishable. The maker of these golf club shafts chose to highlight their qualities in the rain by choosing a black marble background, moistened with a spray of water. Usually shown crumpled or twisted, textiles are perfect for being both background and props for the object being presented. They are widely used for watches, jewelry, and some cosmetics, for which satins and other glossy textiles are popular. Care must be taken to use them with very diffused, side lighting to give texture to their folds. One must, of course, also make sure to use fabrics that have been perfectly ironed and cleaned. Most of the backgrounds mentioned so far are smooth and uniform, but there are also other kinds of backgrounds that we specifically choose for their textures or their color tones. This is the case for the marble slab in the photo above. You can also choose wooden planks or flat stones, or for an advertising shot, create entire scenes that include all different kinds of textures. People generally prefer to use noble materials like leather, wood, and metal—which are very common in packaging shots—but anything can be considered as long as the material’s reflectance, mood, and color are a good fit for the object being highlighted. Nothing says that you have to work with flat backgrounds! You can easily make up all kinds of shapes using things like sand, fluff balls, paving stones, or foam. The only limits are, as always, the harmony of the colors, textures, and reflectance that are characteristic of each kind of material.CHOOSING A BACKGROUND

Diffusion and Reflection

Paper Backgrounds

Matte Plastics

Glossy Plastics

Glass

Mirrors

Brushed Cotton

Liquids

Textiles

Textured Media

Materials and Shapes

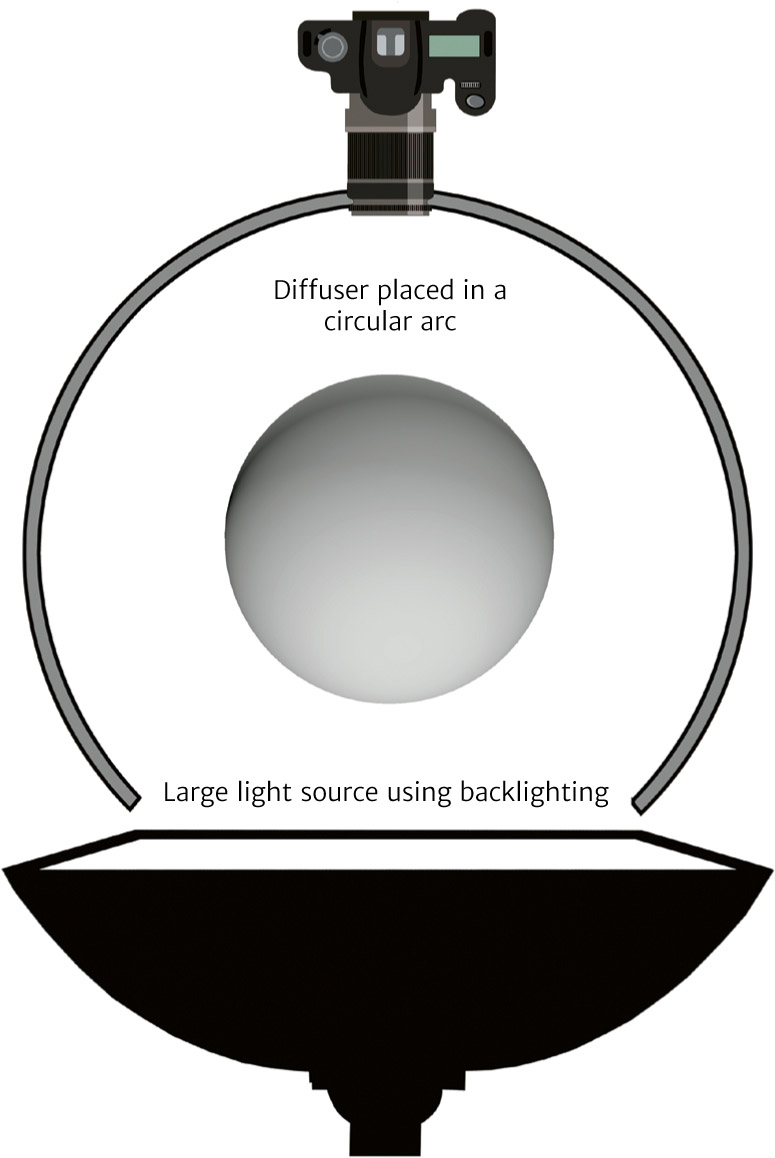

Product photography requires rigor, cleanliness, and organization. Throwing yourself into the lighting and shooting without having properly prepared the products beforehand will mean that you have to spend long hours on post-production retouching. It’s a better idea to carefully plan ahead for all possibilities. Most of the objects you will be asked to photograph are small, so small that all of the tiny defects, like scratches, dust, and fingerprints, will jump out at you once you are looking at the RAW preview on your computer screen. Incidentally, the fact that the object is so small also means that precision work is required in the placement of reflectors and barn doors. Thus, you will need to equip yourself with a series of items and devices to help simplify your work. As I said at the beginning of the very first section of part 1, after carefully checking the overall cleanliness of your studio and conscientiously getting rid of almost all of the dust, you then have to make sure that the object itself is ready to be photographed. Even though we are generally presenting brand-new objects, just out of their packaging, and thus mostly free of scratches and defects, it is still sometimes necessary to remove labels (you can get rid of all traces of glue using a degreasing solvent, which you can get at any hardware store). Make sure to handle the objects with antistatic gloves to avoid leaving fingerprints, or use chamois leather (natural or synthetic) to grip them with. If the object is made of a material that produces direct reflections and it cannot be illuminated without making the reflections appear, you can use an antireflective spray—but note that this kind of aerosol does not completely eliminate the reflections, so it is better to be careful to keep the object outside the family of angles. For plastic objects, an antistatic spray will prevent airborne dust from settling on the object while you prepare your lighting. As a general rule, we always use an aerosol dust remover (like the ones used for computer keyboards) just before we start shooting to get rid of residual dust. In addition to the standard shapers and tripods that are used for lighting, it is sometimes necessary to use a super clamp to clamp the lights as close to the object as possible; screwed to the edge of the table, this clamp is equipped with a spigot stud (a universal-sized brass cylinder that allows most studio lights to be attached to it). It may also be necessary to resort to articulated arms equipped with ball joints to position the light sources in places that are hard to reach with standard tripods and in cramped quarters—even if you often work with an extension or boom arm on your tripod. These arms are helpful not just for holding the light sources in place, but also for supporting backgrounds or accessories held up with transparent nylon fishing line. You will also need to have clamps of various sizes on hand for the different situations you might encounter. HANDLING, PREPARATION, AND SUPPORT MATERIALS MOST COMMONLY USED MATERIALS IN OBJECT PHOTOGRAPHY When it comes to one of the most essential accessories in product photography, namely diffusers, the offerings available from studio equipment manufacturers are actually quite poor. You will constantly need small diffusers, often arranged in circular arcs, to provide the right kind of light for rounded objects, like jewelry or soda cans. I have solved this problem by using 3-mm-thick sheets of translucent PMMA (plexiglass), which are made for diffusing LED lighting. I round them by stretching them and softening them with a thermal cleaner. Make a point of having several of these, of various sizes, on hand; they will be very useful. You can also make frontal diffusers in which you make a round opening for the camera lens, which will avoid frontal reflections on very glossy, spherical, and cylindrical objects. And finally, you can get large commercially available diffuser panels (make sure they are mobile) to even out your rear and vertical lighting; for use when lighting objects like spoons, for example. The objects that we need to photograph rarely stay in the perfect position by themselves! Small transparent plexiglass blocks of various sizes and shapes can be used as wedges; these do not produce problematic shadows or reflections. For opaque objects, commercial mounting putty, which you shape into the appropriate form, can be a good solution. You can also suspend the object using a fishing line attached to a mobile bar so that the entire arrangement can be easily moved without having to retighten the line. This is a good system to use for light objects, but you will have to do some editing in Photoshop to get rid of the line. Transparent objects, like perfume bottles, can be submerged in an aquarium filled with clean water. By limiting the phenomenon of refraction, we can obtain perfectly delineated photographs.SUPPORTING MATERIAL

Preparing the Object and the Workspace

Maintaining and Arranging Backgrounds and Lighting

Maintaining and Arranging Diffuser Fabric

Maintaining and Arranging the Object

In product photography, the tripod is an indispensable accessory. Let’s look at how to choose the best one. Whether you’re shooting a cosmetics line, where every product has to be photographed at the exact same height and distance; taking several different shots for a composite photo; or just needing to position the camera at a precise spot with respect to the reflector panels, it’s impossible to take professional product photos without a tripod. We have seen how crucial the position of the camera is in relation to the lighting, especially for the issue of reflections produced by the families of angles. It is also often necessary for the shooting equipment to be placed in a specific position at a strategic angle for the lighting and rendering of the object. This is only possible, and comfortable, if you are able to position the camera precisely, which implies the use of a tripod and a well-calibrated ball head in order to capture the ideal angle for the shot. And given that the light sources and the diffusers, sometimes even the object itself, often have to be moved slightly, it would be absurd to try to work freehand, wasting time constantly trying to reestablish the perfect angle. We often have to photograph an entire product line of related objects, such as tubes of lipstick, for example. In this case, every object must maintain the same homothetic ratio (orientation of angles) and angle of view as all the others. Thus, we work from a fixed point of view, using a tripod. When creating a composite photo (see the section on composite photos, page 204), it is crucial to photograph the same object from the same point of view, but with different lighting each time. To simplify the editing in Photoshop and to be able to stack the layers easily, the camera must be perfectly fixed in the same spot. For objects that have LED lighting or an LCD screen, there is no other choice, if you’re shooting with a flash, than to lengthen the exposure time in order to be able to work in mixed asynchronous light. Again, this is only possible if the camera is completely stable. There is such a plethora of tripods available on the market that it can be difficult to know where to start. Here are the features you’ll want to consider when choosing a tripod: All manufacturers indicate the maximum weight for each model of tripod in their product sheets. Don’t forget that the tripod will be holding your camera and a lens, and you don’t want to let those fall! To make sure that you are getting a stable photographic tripod with an excellent weight/stability/size proportion, do the following: add up the weight of your camera and your heaviest lens and then multiply that result by 2.5. Depending on the objects you’re photographing, you will sometimes have to work very high up and other times down low, thus the tripod will need to be able to carry the camera from a height of ten inches all the way up to six or seven feet. Two elements can influence its minimum and maximum height: the presence of a center column and the legs. For product photography, choose a tripod with a tilting center column, which you will need for radical bird’s-eye views—and note that you will have to think about buying a counterweight to make sure your equipment stays stable when the column is tilted. But the most important thing is the ease that a column gives you: it is much easier to play with the height of the center column than the height of the three legs of the tripod every time you want to make an adjustment. The issue of the spacing of the legs is not critical in product photography, because we are generally working on a flat floor, but it can be an important consideration if you’re working outside, where you will need to be able to adjust the spacing of the legs individually and irregularly—this is why we do not generally use tripods with a crossbar fixing the legs in place; those are mostly intended for video shots. Example of a setup for a shot: the tripod plays a central role. The issue of the tripod’s weight is not crucial in product photography; you will rarely need to transport the tripod over long distances (of course, if you also use the tripod outdoors, the weight will become an important criterion). Heavy tripods (generally made of aluminum) are cheaper than the very light ones, which are made of carbon. If you are trying to equip a studio, then weight can be a plus, especially in terms of stability; if you are trying to limit vibrations as much as possible, then choose carbon, as it has greater absorptive power. There is a specific kind of ball joint tripod head for every situation and every kind of photography. For ease of use, ask yourself the following questions: In terms of weight, you will need to make the same calculations as for the tripod: the weight of the camera plus the weight of the heaviest lens, multiplied by 2.5. For attaching the ball head to the tripod, the screws on the top of the foot plate are almost always 3/8-inch screws—but make sure that the ball head you have chosen conforms to this standard (if not, you can buy adapters). The next question is the mounting plate, a small accessory that is attached to the body of the ball head and allows it to be secured to the camera. The plates usually have a 1/4-inch thread, which corresponds to the diameter of most camera mounts, but do make sure that they are compatible. Also pay attention to the size of the plates: they are not standard (some brands, like Manfrotto, make plates that only work with their own brands). There are many different ball heads: fluid heads, 3D ball heads, pendulum ball heads, pistol grip ball heads. The fluid heads are placed on a sphere that allows the camera equipment to be tilted into all positions (vertical, horizontal, and flipping from portrait to landscape). They are well suited to product photography but sometimes lack precision (a single notch serves all the different axes). 3D, or three-way, ball heads are equipped with three knobs to determine horizontality, verticality, and tilt: this is perfect for product photography because of its precision. Pendulum ball heads work like a pendulum (as their name implies): while they are well suited to fashion or sports photography, where you need to be able to change the angle of view quickly, they should be avoided for product photography. Pistol grip ball heads (or joysticks) are equipped with a trigger: when you press the trigger, it releases the movement. Even though these are easy to handle, they are generally imprecise, and not well suited to product photography.TRIPODS

Viewing Angle Accuracy

Repeated Shots and Composite Photos

Light Quantities and Long Exposures

Choosing Your Tripod

Choosing Your Ball Head

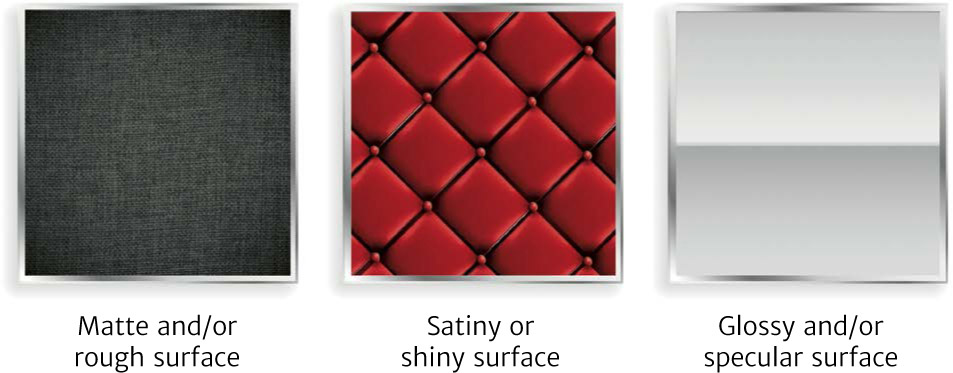

Making a solid preliminary study of the objects you’re photographing allows you to discern the right lighting and shooting strategy. Before you even begin to decide about what lighting to use or what methods to employ, you need to establish a checklist of the particularities of the object. The more precise your checklist, the easier it will be for you to define the lighting parameters and the constraints of your shoot. The very first thing to do is to handle the object, wearing gloves, and look at it under a perfectly white, hard light. By changing its orientation with respect to the light, you will see its texture, glossiness, and flaws appear and you will be able to observe how it reacts. This will also allow you to identify its specific shape and anticipate how and at what angle you will place it on the packshot table, find out whether it is light enough for the use of fishing line, or whether it needs to be filled with liquid or have labels removed. If you do it right, this preliminary work will save you a great deal of time later on. Let’s go through the various things that need to be checked. Handling the object under the light, you will be able to see very quickly whether it produces specular, direct, or diffuse reflections. Depending on its age (old objects are often glossy or oxidized) and its properties, it may also be that the reflections on its various parts are not all the same kind. In that case, observing the object will allow you to determine the ideal lighting with respect to the families of angles and which side is best suited to the lighting you have in mind, as well as plan what accessories you will need for lighting and shaping. Handling an object in the light also brings out any textures (some of which can be hard to see if the light is not falling in just the right way) and will allow you to determine whether those textures are more pronounced in grazing side light or in direct reflection—in reality, it all depends on the orientation of the textures. This is true especially for leather and certain types of plastic. Then, with this information in hand, you can decide whether you want any given texture to appear. DETERMINING THE CONDITION OF THE SURFACE Without a precise knowledge of the material that makes up the product, you run the risk of overlooking the lighting that would bring out its particular nature. A glossy black plexiglass cube looks almost exactly like a smoked glass cube or a black polished steel cube. But each of these will react very differently to light: the plastic cube will produce fairly diffused direct reflections, the steel one will create slightly wavy direct reflections, and the glass one will produce very sharp and perfectly straight direct reflections. DETERMINING THE DIFFERENT KINDS OF TRANSPARENCY When dealing with a transparent or translucent item, the material out of which it is made becomes crucial: a transparent glass bottle will not refract light in the same way as a crystal ball; the direct reflections generated by frosted glass will be different from those generated by a translucent plastic drinking cup. A crystal ball is placed in front of one of my photos, and the image appears inverted because of refraction. For transparent glass, colorless or not, it is essential to use rim lighting. The refraction of the bottle’s silhouette will be more pleasing if the bottle is filled with a colorless liquid (water, or better yet, transparent mineral oil, such as paraffin oil, whose refractive index is close to that of glass). For this type of material, if we want to obtain visible reflections, we will place light sources within the family of angles, while taking care to over-diffuse the light sources (softboxes, in front of which mobile diffusers have been arranged). For frosted glass, the lighting can come from anywhere because this kind of glass essentially produces diffuse reflections. For transparent plastic, backlighting is required, but we have to use harder lights than we do for transparent glass in order to get visible reflections (generally softboxes, but without mobile diffusers). For a flat surface, such as a window, lighting at right angles will create a phenomenon of complete transmission: the glass will be invisible, but it will create visible direct reflections in all other directions. Finally, we need to look at the shape of the object. We know that the kind of lighting we use and where we place it will be different depending on whether the object is flat, polyhedral, cylindrical, spherical, concave, or convex, in order to give the best sense of the shape and allow it to be grasped by the viewer. Its reflections need to be correctly positioned, the differences in shading depending on the shape must be visible, and so must the differences in contrast between the protrusions and hollows if the object is concave. DETERMINING SHAPES Let’s look at the example of the icosahedron, the twenty-sided polyhedron shown above. As shown, with its three forward faces lighter than the seven other ones, it looks convex. But if we had used a concave version of the same shape, with the light placed along the exact same axis, the result would have been the same. To make the sensation of a hollow visible, we would have had to light it from above and create a shadow on the upper part of the concave area. Next, we have to precisely determine the object’s colors (see the following section), and then anticipate how they will react to the environment, light, and props being used. The color of the studio’s walls, and even of your own clothing if you are working with a material that produces specular reflections, the color temperature of the lighting if it is not perfectly white, and the reflections produced by a colored mount or prop can all have an impact. Of course, each object is not just cubic, glossy, or transparent. It will often be composed of materials with multiple characteristics, like the microwave oven shown below: its glass window produces direct reflections, while the rest of the object, covered in matte plastic, produces only diffuse reflections. The same is true for the blender in the illustration: the pitcher is transparent, while the base is opaque. In this type of situation, we always give priority to the material that is the most complex to light in terms of placing the light sources. For the oven, that would be the glass; for the blender, it would be the transparent pitcher. DETERMINING THE COMPLEXITIES OF THE SHAPE/SURFACE/MATERIALTYPOLOGY OF OBJECTS

Observing the Object

Defining the Kind of Reflections

Texture

Assessing the Material

Defining the Transparency

Assessing the Shape

Defining Colors

Managing Complex Objects

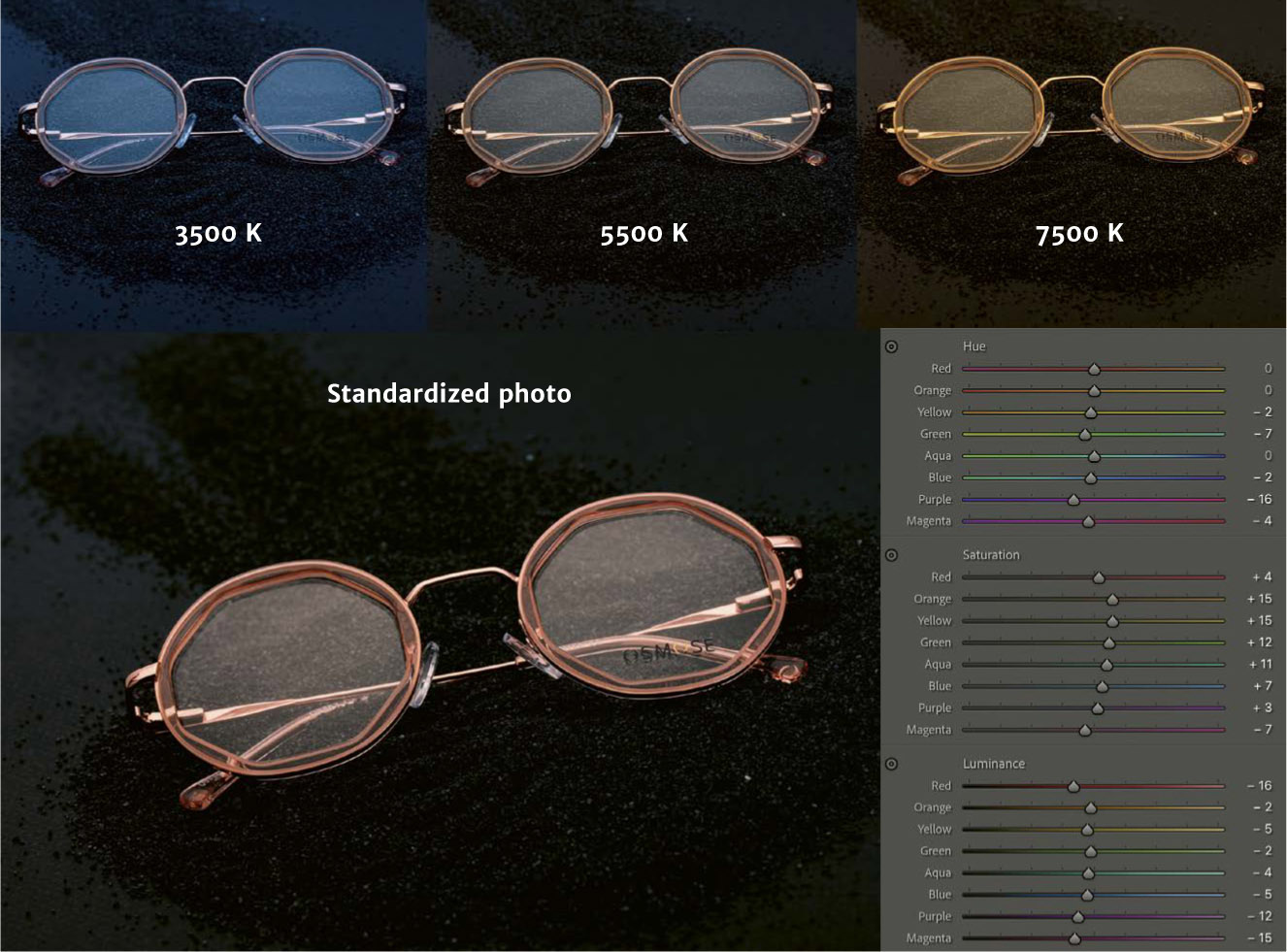

In commercial photography, it is absolutely essential that the colors of an object in a photograph are faithful to the original object. Without a rigorous calibration of the elements in the imaging chain and discipline in your working method, there is no way to obtain the exact same color in your photo as in the actual object—and a discrepancy there would, of course, be inexcusable for a catalog photo or an advertisement. Thus, you must follow a precise procedure that you reproduce every time you change the lighting. As I discussed in the section on page 53, we perceive the color of an object because there is only one wavelength that it reflects, while it absorbs all the other colors. Thus, if we project a red light onto a green object, it will look black (having no green to reflect). Therefore, it is not so much the real color of the object that we are interested in here but the wavelengths that are present in the lighting. Moreover, the spectrum of the light reflected by the illuminated object, which determines the nerve impulses sent by the retina, varies widely depending on the lighting, while the color that we perceive does not change. This phenomenon is called color constancy. But this is not the case for color sensors, which react according to the light spectrum that reaches them: an object illuminated by an orangish light will not produce the same signal as when it is illuminated in blue. The only way to make the color look the way it does in reality is to calibrate the camera—a procedure that will need to be repeated every time the lighting, and the ambient light, changes. We thus “inform” the camera by giving it a surface recognized as white in the main light and then weighting the signals of the colors interpreted by the sensor: this is white balance. The same object photographed at 3500 K, 5500 K, cand7500 K. A TSL (Tone, Saturation, Luminance) profile was created by photographing a palette of colors in the same lighting conditions, using the SpyderCheckr software. The screen was calibrated using a SpyderX Elite probe. A Lastolite gray card The standard exposure calibration was set at 18% gray by Kodak in the 1930s. This is still used as the benchmark for measuring exposure and for color calibration. To standardize our white balance, then, we use a gray card. To simplify, a gray card reacts as if it is composed of 18% pigments that reflect light perfectly cand82% absolute black pigments. To make it clearer, we call it “neutral” gray because it includes as much red and green as it does blue: in RGB values, thus, neutral gray corresponds to a value of 118 (with a tolerance from 114 to 122), with the RGB including more levels in the dark tones than in the light ones, because human eyes are better adapted for distinguishing dark tones. I should note that manufacturers often offer a version of these charts that includes an X for the sake of focusing. Using a neutral gray card is very simple: 1. Place the card in the same place as the product to be photographed, under the same lighting conditions. 2. Measure the exposure using an independent exposure meter and set the camera to the measured value, without optimizing the exposure. Or proceed in reverse by adjusting the power of the light sources so that their measured illumination will correspond exactly to the camera settings. Because the photo is being taken in RAW, the white balance chosen for the first shot doesn’t matter. 3. Take a photo framing only the gray card. We activate the custom white balance function of the camera by choosing this shot. 4. Take a second photo including the object, the neutral gray card, and a color reference card (following photo) side by side. This second shot will be used to finalize the calibration of the development software. It is important to repeat this operation every time there is a change in the lighting. The RAW file format saves the values of the light received by the sensor and the adjustment of the white balance separately. The white balance adjustment performed by the camera is thus only an indicator during the post-production process, where it can be precisely corrected without damaging the file. But before calibrating the image itself, the screen that is used to view it must be calibrated. This instrument is seldom used by amateurs, but it is crucial for anyone who wants to obtain perfectly true colors. High-quality calibrators are now available for under $200. You will need to go through the following calibration process regularly, because screen color rendition varies depending on how long the screen has been turned on and how old it is: 1. Install the software supplied with the calibrator on your computer. 2. Position the calibrator on the screen (the calibrators usually come with an attachment system). 3. Once it has been launched, the calibration software will compare the colors of its palette with the actual display and will create an ICC colorimetric profile (a small file of a few dozen KB) that will correct the colors to keep them true. There are automatic modes, but I suggest you carry out a complete calibration, nonetheless. You will be surprised at the quality of the result. Photo of a reference palette including a neutral gray card placed in the exact same position and under the same lighting conditions as the pair of glasses on the previous page. The camera setting is what was measured with an independent exposure meter. You can save a lot of time by editing a colorimetric profile specific to your camera, using a color reference chart and the appropriate software. Simply photograph a calibrated color palette with each change in the light, and use the dedicated software to create a reference profile, which will then be interpreted by the development software. But note that this profile will only work for photos that are illuminated exactly the same way as the reference shots; every time you change the lighting, you will have to redo this operation. All development software (Capture One, Lightroom, Camera Raw, etc.) is equipped with a white balance selector tool. It is represented by an eyedropper next to the white balance editor. Simply import the photo of the neutral gray card, click on it with the eyedropper, and the software will apply the appropriate correction. Then duplicate this calibration and apply it to all of the photos that were taken with that lighting, under those conditions. Import the photo in Capture One (or your software of choice), select the white balance selector tool, and click on the neutral gray card. This operation will allow you to calculate the necessary white balance.RESPECTING COLORS

Color and White Balance

The Neutral Gray Card

Standardization in Post-Production

Monitor Calibrators

Creating a Color Profile for the Camera

Calibration Using Development Software

It is rare for photos of objects not to need any digital editing. However, we can reduce the amount of editing we have to do by carefully managing the lighting and shooting. This book is not meant to teach you how to do digital editing, something I do little of and that is also explained in detail in many other books. My aim here, instead, is to emphasize how to prepare the shot so that any editing will be quick and successful. After years of practice, I can state that most editing for product photography can be preempted by methodically preparing the product, carefully managing the placement of the light and the measurements, precisely positioning the diffusers and barn doors, rigorously managing the imaging chain (especially in terms of color), and knowing how to control your camera. As an example, I have used a lipstick tube placed on a transparent plexiglass wedge in front of a softbox. A reflector is placed to the right of the image. Looked at raw, before adjusting the white balance, the image shows a large number of problems, which could require dozens of minutes of editing. But most of the problems have very simple remedies: positioning barn doors to make the tube’s silhouette more precise and to unify the reflections on the front section, using a gray card to calibrate the colors, handling the object with gloves, etc. What is left are the defects that are inherent to the specific object we are dealing with here: in this case, the plastic shell is not completely smooth; the lipstick itself has miniscule nodules on its surface because the product was not stored properly; and a few fine scratches can be seen, even though the object was brand-new and in spite of the care I took while handling it. DEFECTS IN THE RAW FILE THAT COULD HAVE BEEN DEALT WITH DURING SHOOTING Here we changed the lighting of the lipstick tube by placing barn doors to either side behind the object, directed toward the front left side, while lighting from the back and from the front right using diffusers. The only editing consisted of erasing the little bumps on the bottom of the tube, the plexiglass base whose edge had been showing, and the fingerprint. Most scratches and bumps can be corrected using the frequency separation technique. There are a lot of great, in-depth tutorials online demonstrating this technique. For now, simply note that in Photoshop, this technique will allow you to separate the image into two separate layers—one including the textures, the other including the colors—that you can edit separately. The advantage of this process over the usual correction tools (the clone stamp tool, sample source overlay, etc.) is that you can limit the editor to working on only one of the two layers. Thus, for instance, you can make a scratch disappear by duplicating a nearby, contiguous area that has no flaws in the texture layer, without affecting the color. And if the issue is a color problem, you can do the same thing in the color layer, without affecting the texture. I used this process to eliminate the scratches and irregularities on the lipstick shown above left. For problems connected with the lighting, and with reflections that appear in the wrong place because the object has a shape defect, you can use the dodge and burn technique. In this case, on top of the layer of the image, you add a new layer filled with 50% gray (in Photoshop: Edit > Fill, and then choose 50% Gray from the Contents drop-down menu). Then, if you choose Soft Light under the blending mode option, this layer will become invisible. Using a very soft brush, set to a low opacity (less than 8%), you can then paint the areas in the gray layer where you want to fix something by applying black (to darken the areas) or white (to lighten them). An example of dodging and burning. On the left, the original photo; in the middle, the gray layer to which we applied black and white with the brush; on the right, the photo once the gray layer was made visible using the Soft Light blending mode.PHOTO EDITING

What Can Be Corrected During the Shot

What Requires Editing

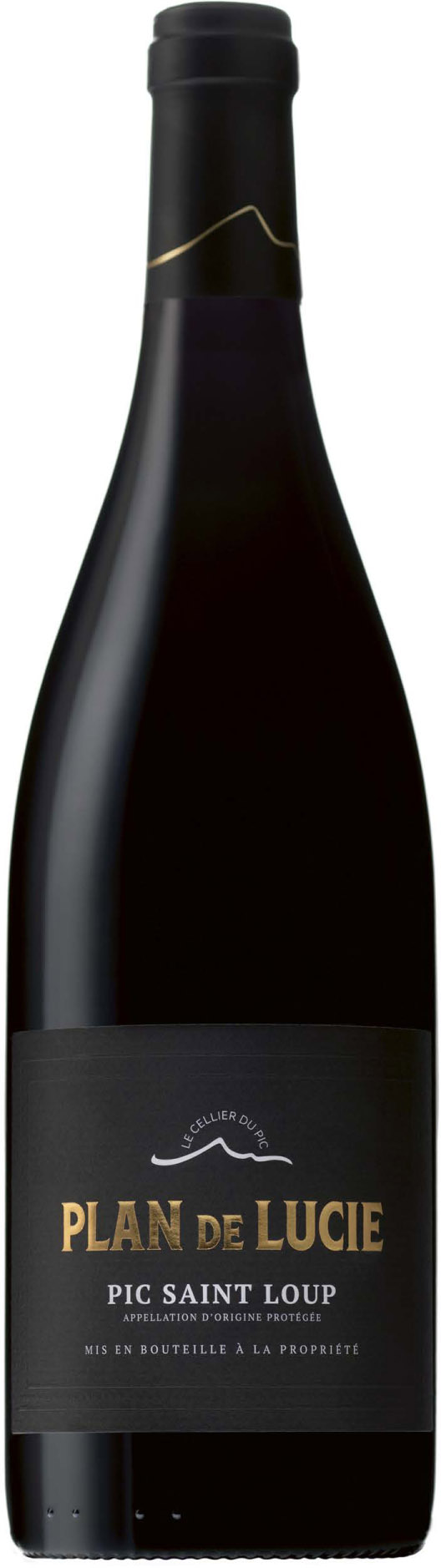

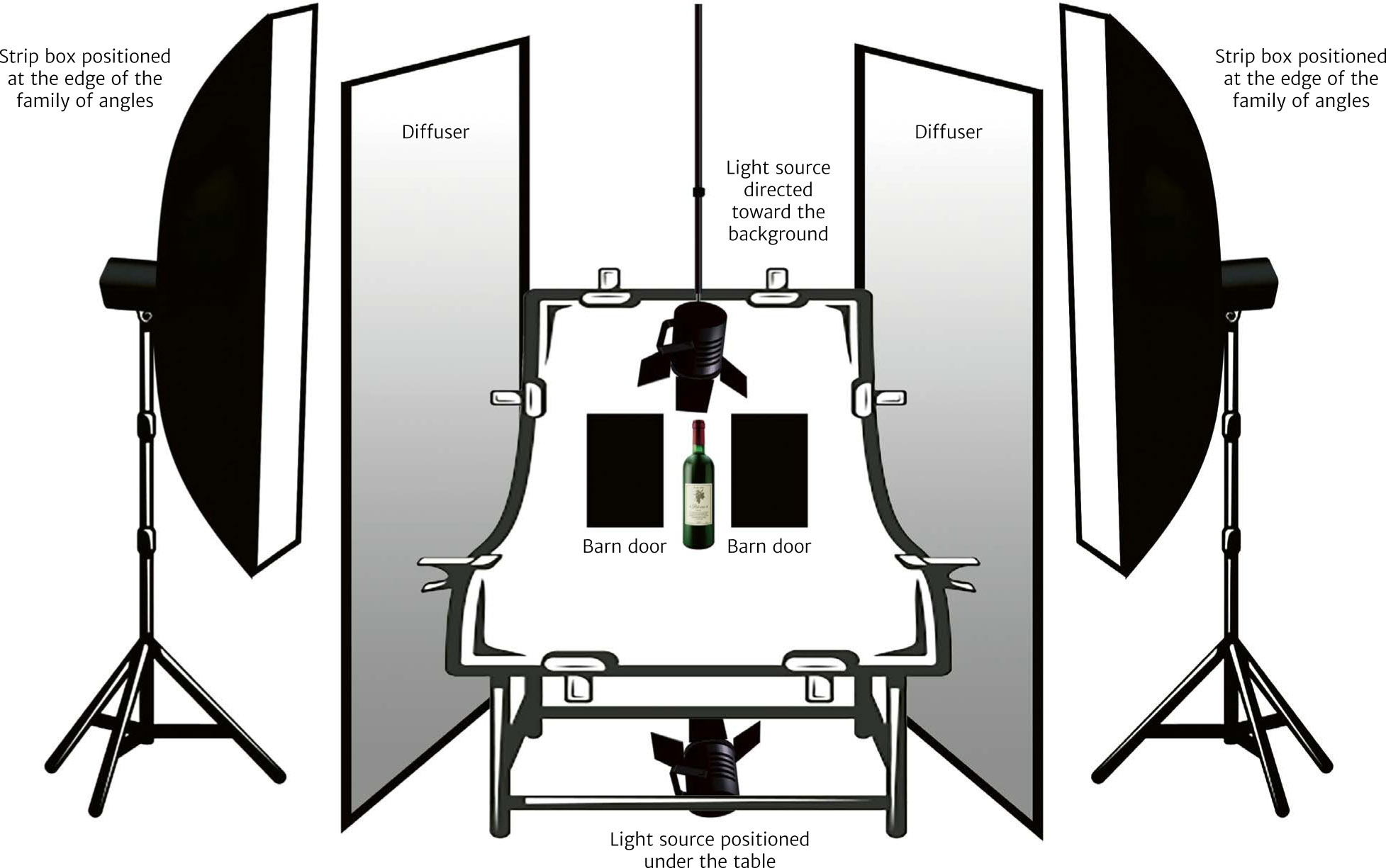

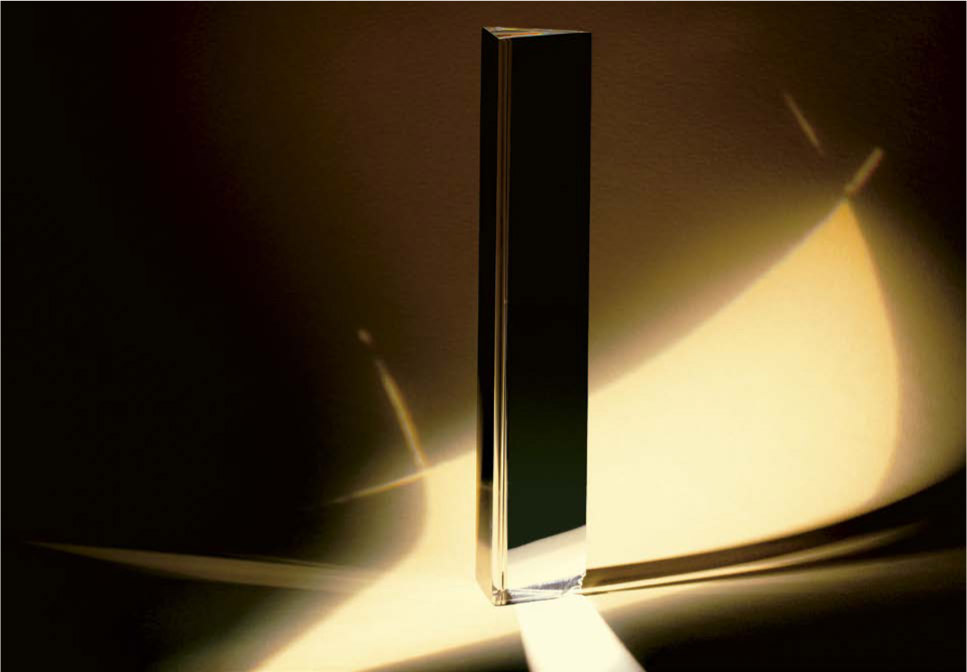

Lighting wine bottles is a typical assignment for product photographers. There are countless winemakers, and the vintages change every year. But photographers who truly excel in this field are rare because it is a very difficult discipline. In photographing wine bottles, the lighting difficulties add up: we have glossy, cylindrical glass; a matte label that is sometimes embossed and gilded; there is stenciling on the glass that produces hard-to-control direct reflections; the background must be completely white for catalogs; the management of linear reflections on the edges of the bottle; the issue of lighting the stand or holder without creating reflections on the base of the object; and so on. Everything comes together to make this a very difficult assignment. The best way to deal with it is to address the problems one at a time. Before photographing a bottle, always make sure to ask the producer to choose products with no defects; they will not, however, always be able to do so. Because the bottles are packaged in industrial production lines, it often happens that the seam (the visible mold mark resulting from the press process) appears on the front of the bottle. The same is true for stains and tears on the labels and flaws in the stenciling. In each of these cases, the only solution is photo editing. Before starting anything, you will need to make sure that the bottle suits the lighting you have planned for it by examining its characteristics and possible flaws, the types of reflections that can be expected, etc. This examination will also allow you to determine whether you can photograph the bottle all at once or whether there are lighting issues that are impossible to reconcile (such as the presence of a medallion that contradicts the lighting of the bands, embossing on the label that will require that it be directly lit, etc.), forcing you to create a composite photo (see page 204). Then, when you have several bottles to photograph, you will be able to organize your work so that you don’t have to change the lighting for each one. An example of the lighting of a bottle of red wine for a catalog. This photo, illuminated using the methods laid out in this section, did not require any editing. On the golden part of the lettering, we can clearly see the influence of each light source. Next, you will prepare the product, making sure that it is perfectly clean (glass always attracts dust), that the capsule (protective sleeve on the neck) is well centered (you can just rotate it by firmly pressing on the neck), and that you have straightened out any folds in the label. Bottles are generally photographed on commercial pack-shot tables, but you could obtain a similar result by placing a sheet of translucent plexiglass over two trestles arranged in front of a white background. Just be careful that the space behind the arrangement, as well as on both sides of it, is wide enough for you to be able to set up your diffusers and light sources. It will make things much easier if you shoot in a place where there is no lighting other than what is intended for your product, with a black background behind you, and wearing black yourself: glass’s highly reflective surface works like the glossy sphere we discussed on page 87, where everything within the family of angles that is light-colored or luminous will show up. The ideal setup is to position the object on a stand solid enough that the lighting meant to illuminate the lower part of the image is not reflected on the bottom of the bottle. I use four-inch-high matte-black cylinders, with a slightly smaller diameter than that of the base of the bottle. Make sure that it stays perfectly straight. The stand can then be removed in post-production, using a linear filter in Lightroom if the bottom of the bottle is flat, or using an area selection tool in Photoshop if the bottom of the bottle is serrated. Start by placing a light source directed toward the background, in rim light, so that the entire space behind the bottle is white. It doesn’t matter whether the light is soft or hard, but it’s a good idea to use a zoom bowl equipped with barn doors to direct the light properly. STANDARD METHOD FOR LIGHTING A BOTTLE OF RED WINE The light on the background is then measured at +3.33 EV in relation to the camera setting (or more if the object is very far from the background). For example, when the lighting of the background is measured at f/18 for a camera setting of f/5.6, the background will be completely white. Of course, with this much light, there is also the risk that the edges of the bottle will be massively overexposed; but this can be mostly dealt with by making sure that the background is as far away from the product as possible. Proceed in the same way by positioning a light source under the table to accompany the reflection of the rim light. This light should not be very strong, since the table is very close to the bottle; this light is only meant to accompany the rim light, which already produces a significant reflection on the table (see diagram on page 125). The main issue here is to even out the light on the bottom of the image and give a little light to the label. PLACEMENT OF BARN DOORS FOR A SHARP SILHOUETTE This light, nicely diffused by the plexiglass of the table, will join the two side strip boxes to even out the lighting on the label. It should be adjusted (using the power measured on the table, with the lumisphere directed toward the light source) to the same value as the camera setting. Add +0.3 EV if the label is dark or black. We have already noted that when the backlighting is strong enough to create a perfectly burned-out background, there is a risk that its reflection will create an unappealing fade-out effect on the edges of the bottle. To avoid this, and to produce clean, well-defined edges, you will need to position two barn doors behind the object, one on each side (see diagram at left). Given that glossy cylindrical objects have a family of angles of 280°, like spheres, the barn doors will have to be positioned outside the family of angles—at least at 220° cand140°. They will, of course, appear in the photograph, but the bottle will be perfectly illuminated, and you can just crop the photo to remove them. In Europe, the tradition is that in lighting bottles of red wine, you must have one or two bands of direct reflections, more or less subdued depending on the category of wine, on at least one of the two sides of the bottle. The number of bands of reflection and their quality will vary depending on the grape variety, the appellation, the winemaker, and the photographer (see photo on following page), but the fact remains that for fine wines, very soft reflections are created, and for lesser wines, slightly harder reflections. There is no kind of light shaper that is perfectly suited to projecting these reflections, which must be long, narrow, and extremely diffused. You can use reflected lights, projecting the light from two strip boxes onto reflectors placed at 260° cand100°: the light quality will be perfect, but the width of the bands will be hard to correct. My advice is that you use two strip boxes behind two large diffusers instead (see diagram on page 125), both of them positioned in the same way, which will avoid climaxes in the reflections. By playing with the distance between the strip box and the diffuser, you can easily manage the quality of the reflections and comfortably decide on the result you would like to attain. One of the main advantages of this arrangement is that, along with the lighting positioned under the table, it allows you to illuminate the label as well. With two reflections, the light on the label is evened out and will not need any intervention in post-production (i.e., dodge and burn; see previous section). POSSIBILITIES FOR LIGHTING BOTTLES OF RED WINE The label does not generally need its own dedicated lighting. However, if it is embossed or has glossy lettering (usually gold or silver), you may need to place a light source along one of the frontal axes, which will produce an unsightly reflection in the glass. Then you will have to take two shots: one arranged as described above and one in which you only light the label. The two photos can then be combined in Photoshop, with only the label selected for the second shot. VOCABULARY The cylindrical shape of the bottle allows for radical “showerhead” lighting. (By “showerhead” lighting I mean the light is positioned like a showerhead in relation to the product; see the illustration on page 93). When the bottle also includes engraving (usually a coat of arms, such as the Occitan cross or cross of Languedoc for wines from southern France), you will have to light that separately, as you do for label embossing. Example of steps for positioning the lighting: 1. Place a light source directed toward the background and two barn doors within the family of angles. 2. Set up a light source underneath the table to light the bottom of the bottle and, to some degree, the label. 3. Place a strip box on one side of the bottle, at an angle of approximately 100°. 4. Arrange a diffuser in front of the strip box and a small white reflector at around 100° to direct the light onto the medallion. For this shot, because the presence of the diffuser and the reflector will give too much light to the engraving, the medallion will need to be addressed with a third photo. Because of the shape and the material of engravings, they are unable to produce diffuse reflections. No matter what the lighting, you will never achieve even lighting across the entire engraving. Therefore, you will need to use a snoot, equipped with a honeycomb grid and positioned in a vertical showerhead position, directed toward the engraving. This will produce direct reflections onto all of the convex surfaces situated within the same angle, leaving the rest in shadow. You just need to be careful to make the ray of light narrow enough so that it does not also light the bottle’s shoulders. When the capsule is light-colored, no additional lighting is needed, but for black capsules you might need to plan for more lighting. If the light is narrow enough (using a snoot equipped with a honeycomb) and directed horizontally at the level of the capsule, the result can be satisfactory. You can also place a barn door below to avoid possible reflections on the glass. Some bottles have a medallion, either awarded by an agricultural competition or indicating some special feature of the wine and meant to attract the consumer’s attention. These are stickers that are generally positioned between the capsule and the neck of the bottle, and they are often gold or silver. A medallion requires the same kind of lighting as the capsule, but the medallion is often too low for it to be lighted without risking creating reflections on the glass. Thus, a separate photo must be taken and then integrated as a layer in Photoshop. Likewise, there are often cardboard sleeves (printed cardboard placed on the bottle’s shoulders and wrapping around its neck). They usually do not cause any problems, because they react to light the same way the label does. If not, they should be treated like the capsule. Most bottles of red wine look opaque, in which case the color of the liquid is not crucial. But for light red wines, such as a Beaujolais Nouveau or a Bordeaux Clairet, the shot will have to be carefully calibrated using a gray card. Every wine expert will tell you that the color of the wine is both a commercial tool and the identity of the product. Also make sure not to oversaturate the colors in post-production.BOTTLES OF RED WINE

Before You Start

Preparing the Bottle

Setting Up the Object

Lighting the Background

Lighting the Base

Producing a Sharp Silhouette

Producing Even Reflections on the Edges

Lighting the Label

Lighting the Engraving

Lighting the Capsule

Lighting the Medallion and the Cardboard Sleeve

Color and Preparation of the Shot

Even though the container is not that different from what is used for red wine, because of their greater transparency, rosés and white wines react differently to light. The question of color, therefore, takes on greater importance. While the lighting of bottles of rosé and white wine seems simpler, because you need fewer light sources, it also requires greater precision, especially in the management of tones and nuances. Unlike for the bottles in the previous section, here the challenge is to make the color of the liquid look as good as possible—it needs to be harmonious, true, and even. The lighting of the back of the bottle is no longer just a matter of lighting the background, but also of providing the luminance and color that match the wine itself. The light source, therefore, is no longer directed from the front to the background, but rather behind the background, so that the light is as diffuse as possible. If you don’t have a standard packshot table available, you can achieve a similar result by placing a diffusing fabric behind the bottle and then, behind that, arranging a light equipped with a relatively large light box. Make sure that the light measured on the diffuser (with the lumisphere directed toward the light source) is +3.33 EV, as with the bottles of red wine. This arrangement will ensure that you have a very soft, even lighting, while limiting the appearance of localized highlights. As usual, you will need to arrange two barn doors at the edge of the bottle’s family of angles to ensure a well-defined silhouette. Also pay attention to making the reflection of the black bands at the edges of the bottle as fine as possible by positioning the covers very precisely. You can make the positioning more exact by moving the bottle to the ideal distance. Think of the edges of the bottle looking as though they had been drawn with a well-sharpened gray pencil. Example of lighting of a bottle of rosé for a catalog. You do not need to light the bottle so as to produce bands of reflections on either side of the front of the bottle; some winemakers, however, will ask for that. The presence of the bands has the advantage that it solves the problem of lighting the label, while keeping the bottle from looking like it is made of frosted glass (see next section). If you’re trying to produce a shot without visible reflections, you will need to use the method for lighting cylinders: a rounded diffuser placed in front of the bottle, with a hole in it for the camera lens to pass through. This will position the backlighting to reflect on the diffuser, so that the front of the bottle is globally illuminated, without any reflections appearing on it—there will, in fact, be a reflection, but since it covers the entire visible surface, it can’t be distinguished. And if, by any chance, the result ends up looking a little foggy, you can just apply a 10% or 15% Dehaze filter in Lightroom. STANDARD METHOD FOR LIGHTING ROSÉS AND WHITE WINES POSSIBLE WAYS OF LIGHTING ROSÉS AND WHITE WINES A behind-the-scenes view of the lighting of the bottle shown on page 129. Three light sources were used: a bowl fitted with a barn door and placed behind the table’s backboard, using backlighting through the plexiglass; a light source on the ground, underneath the table, directed vertically toward the bottle; and a strip box behind a large diffusing fabric, to the right of the bottle. Two barn doors were placed behind the bottle, and a third one to the left of the bottle. If you decide to include visible reflections, then just use the method that has been outlined for red wine, while playing with the dimming as much as possible: move the light source away from the side diffuser so that its luminous flux covers all of it, or even move the diffuser away from the bottle if the light source is too close to it (because the diffuser is not fully illuminated, the source will look smaller, from the point of view of the bottle, than if it were fully lit). Some winemakers and some labels want their bottles of rosé and white wine presented so that the surface of the liquid cannot be seen, so it looks as though the bottle is filled all the way up to the cork. Of course, there is no such thing in reality, because the empty space left underneath the cork at the neck of the bottle prevents the wine from escaping if there is a change in temperature and a resulting increase in pressure. In these cases, therefore, you have no choice but to edit the photo in Photoshop. You can duplicate the color of the wine in the area above the label (which is the most even area in the photo) and then paste it into the empty space, using a layer mask. Then, all you need to do is pass the eraser tool, set to a low opacity, over the area as much as is needed to fill the empty space. White wines and rosés are textbook cases of the need to calibrate the camera using a well-suited colorimetric profile and the use of the gray card and the colorimetric probe described on pages 119–120. The color of the wine is not a coincidence, but rather is the result of meticulous work on the part of the enologist, who has chosen to blend several different wines according to their taste qualities, of course, and the result they desire in terms of color. Rigorous management of the imaging chain and rigorous control of the lighting will ensure that the final color is true, but you must also be careful not to saturate the colors that you obtain in the final phase of post-production: this would have the effect of “pinking” white wines, which is considered to be a flaw associated with poor winemaking—purists would think they looked like “stained” wines, which are wines contaminated by the presence of red wine anthocyanins. In addition, note that the fashion, originating with wines from Provence, is to present ever paler rosés, to give the impression that they are lighter and fresher.BOTTLES OF ROSÉ AND WHITE WINE

Delicate Lighting

Reflections or No Reflections?

Wine All the Way to the Top

Color and Post-Production

Frosted-glass bottles, generally used for white wine and rosé, are becoming more and more common. To illuminate them properly, the light must be extremely diffused. This kind of bottle is produced using a technique called satinizing, in which the bottle is immersed in an acid bath that attacks the surface of the glass, giving it a frosted or sandblasted look (depending on how long it is in the acid). After that, the lighting plays an essential role in emphasizing the impression of a silky finish. After it has been attacked by the acid, the surface of the bottle is no longer smooth, and it can no longer produce direct reflections, only diffuse ones. Thus, there is also no longer any risk of producing poorly positioned highlights. You might therefore reason that any light source, placed anywhere, would work just fine. And this would be true if you were photographing a bottle filled with something opaque, but the challenge here, as in the previous section, is to light the bottle while making the contents look as good as possible, in terms of both light and color. STANDARD METHOD FOR LIGHTING FROSTED-GLASS BOTTLES In addition, even though the bottle only produces diffuse reflections, there is still the risk, if you use lighting that is too hard or too localized, that shiny spots might appear, which would then require editing work. As with all translucent objects, therefore, you need to have a solid strategy for the lighting. The management of the light here involves producing very even lighting behind the bottle so that the color of the wine will be as constant as possible, while also maintaining the tonality that we expect from a cylinder (a gradual change in lighting across the various parts of the shape). As always in such cases, you will need to make sure that you have perfectly calibrated your screen and adjusted your white balance using a gray card, as well as a colorimetric profile on a palette. It’s essential to get the right shade. After that, you will have to place your light sources so that they are well centered—the laws of refraction mean that this positioning will ensure that the light is well distributed across the bottle, and will avoid the presence of discolored or grayish areas along its edges. As with all transparent glass, the strategy of backlighting is a necessity here. To achieve the softest and most even light possible, use the following steps: 1. Position the rim light, equipped with a softbox, behind the bottle, then place a diffusing fabric far enough away from the softbox that it will be lit up over its entire surface. The rim light can also be placed in reflection, as in the diagram on the previous page: pointing backward from the front, it is reflected on the panel located behind the bottle. The light is soft and even, and the setup will therefore be simpler. 2. Arrange two barn doors, one on each side of the bottle, to create a sharp silhouette. Place a sheet of translucent paper in the center (see the behind-the-scenes photo above) to harmonize the lights and give a sense that the color of the liquid has been smoothed. 3. Place two strip boxes along the two sides, behind diffusers, not to create reflections (as would be the case for smooth glass bottles), but to avoid creating areas of low light along the edges, and, especially, to illuminate the label and the capsule. 4. Because this kind of bottle is quite sensitive to grazing side light, do not light up its base from below. We generally place the bottle on a fabric that absorbs light, such as brushed cotton. A behind-the-scenes view of the lighting of the bottle at right. The front of the bottle and the label are illuminated using a snoot equipped with a honeycomb grid positioned frontally at 70°, from above. A brushed cotton sheet is placed under and over the bottle to avoid reflections from above and below, and a sheet of translucent paper is positioned behind the bottle to even out the lighting of the wine. Example of lighting of a frosted-glass bottle of rosé for a catalog.FROSTED-GLASS BOTTLES

Diffuse Reflections

Evenness in the Color of the Wine

Lighting Strategy

Glass bottles generally have a lot of flaws, particularly ones due to uneven thickness of the glass and the presence of opaque particles or air bubbles. We have seen that it is advantageous for a glass container to be shown full, because the presence of a transparent liquid has the effect of evening out the light through refraction. This is true for all the bottles we have looked at so far. But the problem must be addressed anew when we photograph empty bottles. Glassmakers have a rich vocabulary for describing flaws in bottles: streaks, refractive index gradients, inclusions, bubbles, chips, stones, tears, etc. It is clear that laborious editing work will be required to produce a high-quality shot that you can present to your client. The best way to solve the problem is to play with the refraction of light: filled to the brim, the bottle will behave like a magnifying lens, and all the flaws on the interior surface will disappear. You can use water for this, but for an optimal result you will find that a transparent mineral oil, like paraffin oil, works best. You can take this even further: by submerging the bottle in an aquarium filled with water, you can also eliminate the flaws on the outside of the bottle. In this case, it is the whole apparatus of aquarium, water, and bottle taken together that works as a magnifying lens. Of course, flaws related to the inclusion of particles and air bubbles will still be visible because their refractive indexes are very different from that of glass, but most defects will be corrected. As with the wineglass, we proceed using backlighting (a strip box placed behind a diffusing fabric). This light alone may be enough, as with the photo of the flask below, but glassmakers often require there to be a pronounced reflection on the front of the object: to make that happen, a strip box is placed at 90°. This kind of reflection makes it possible to emphasize how polished the glass is while also showing off the bottle’s specific shape. Three bottles, with different shapes and colors, filled with water and photographed using backlighting.EMPTY BOTTLES

Flaws

Filling the Bottle

Lighting

Creating photographic reproductions of pictorial works is a common commercial activitiy for object photography studios. It is easy to see that, more than in any other area, this activity requires absolute fidelity to the original. Reproductions meant for museums, photographs for exhibition catalogs or posters, certificates of authenticity—the list of areas in which a photographer is required is a long one, and provides regular work for professionals. It demands rigorous attention to fidelity in terms of both colors and proportions. The very first thing you have to do is make sure that the orientation of angles (homothety) in the shot is perfect. You do this by placing the camera lens at the level of the center of the painting, at a perpendicular angle to it. This requires setting up the camera on a tripod at the necessary distance to maintain an average diagonal angle of view of 24°. Thus, for a 12-inch painting, we use a 135mm lens at sixty inches away; for a 6.5-foot work, we use a 50mm lens with the camera 10 feet away (see the table on page 49). These precautions will allow you to guarantee that the proportions of the work are reproduced perfectly, matching the artist’s original work. The lighting is arranged so as to achieve the most even and largest light possible, while keeping its contrasts as minimal as possible. To do this, very diffused lighting is placed more than 6.5 feet away from the object—traditionally, this light consists of two light boxes at 45° on either side of the painting. For textured paintings, we shall see that we have to add diffusing fabrics to minimize certain localized shadows. But hard lighting (bowls, lenses, shapers without diffusion) cannot be used at all. As a rule, you should also avoid frontal lighting, which could allow the shadow of the camera (and of the photographer, if you aren’t using a remote control) to appear, and could generate very uneven lighting—the central climax area could cause highlights to appear on the painting. STANDARD METHOD FOR LIGHTING PAINTINGS Most of the works that photographers are asked to reproduce include material effects that you will have to try to render in the shot, while trying not to allow the shadows that they might produce to distort the image. To do this correctly, you will have to understand some things about painting. Watercolors allow the grain of the paper to show through, and they accentuate it, so the grain must therefore be visible in the shot. Some paints are mixed with extenders (most often gypsum, kaolin, or lime); these are used to add dimensionality to the painted surface, and you can make them show by adding a third light box at 90°—in other words, a grazing side light meant to bring out the textures through slight shadows. The same is true for oil paints or acrylics mixed with sand, sawdust, shavings, or undercoats of coarse canvas or crumpled paper (as used by the Surrealists). For other techniques, such as the palette-knife paintings that were common among the Impressionists and, earlier, Fragonard, or material work using sponges or brushes, it may sometimes be necessary to slightly lower one of the two light sources in the standard arrangement (by 0.1 to 0.3 EV) to make the technique visible. When the texture of the canvas or the paper on which the work is painted plays an important role, as in Kandinsky’s and Egon Schiele’s watercolors, you will obtain a more elegant and more precise result by using a camera without a low-pass filter, such as the Canon 5DSR or the Nikon D5300. This kind of equipment, which allows you to represent high-frequency information such as repetitive patterns (the screen of a canvas or the grain of a paper) without an anti-aliasing filter reducing the sharpness of the image, will provide good results. This painting, made by the children of a primary school in the Hérault department in France, was made up of seventy-two ten-inch cardboard squares, sewn together with strings. Many of the works that need to be photographed come in a variety of shapes. Collages, triptychs, stacked frames, 3D effects—the possibilities are endless. I remember, for instance, a painting by a Russian visual artist: it was red all over, and the very tightly woven cotton canvas was stretched in the center over a wooden pyramid, creating very different material effects depending on where you stood in relation to the work. In cases like this, you will need to use the lighting methods adapted to each kind of shape, as we discussed earlier: one of the two light sources will have to be somewhat minimized so that a slight shadow can indicate the presence of the pyramid. An accurate calibration to the color palette is crucial, especially if the photo is meant for reproduction or is being used for a certificate of authenticity. You will need to pay attention to the perfect measurement of your lighting (optimizing it during shooting, and correspondingly underexposing it during development), a good white balance using a gray card, the creation of a photographic reference on a color palette, and the precise calibration of your screen using the monitor calibrator. Remember that if the work includes materials that produce direct reflections, you will do well to wear black to avoid creating your own reflection as well. A behind-the-scenes view of the lighting of a painting.LIGHTING A PAINTING

Preparation

Lighting

Issues with Texture

Particular Shapes and Materials

Faithfulness to Colors and Reproduction

Presented for their own sake or as part of another object, mirrors can be found in many situations. What I want to give you here is not so much a lighting method as a philosophy of photographing. In photography, a mirror is essentially nothing but a reflection. It is up to us to decide what it is going to reflect. Thus, even before we think about what kind of lighting we use, we need to decide what we want to see appear in the image. More than any other object, a mirror must be perfectly cleaned before it is photographed. Fingerprints, static dust—everything will be visible in the final shot. To clean the mirror, I suggest spraying it with a mixture of hot water and white vinegar (lemon juice also works well), and then wiping it off with a microfiber cloth, using horizontal strokes from top to bottom. The same mirrors, lighted along different angles. The lighting in the bottom photo does the best job of showing that this is a reflective surface. What you need to do now is determine what kind of result you’d like to obtain (see diagram below). If the camera is placed entirely within the family of angles of the light source, the mirror will appear completely white; if outside, it will appear completely black; if it is between the two, it will be partly black and partly white. MANAGING REFLECTIONS IN THE MIRROR Mirrors are traditionally shown progressing gradually from white to light gray. To create this effect, position a light source whose reflection is larger than the total surface of the mirror, usually by setting up a large reflective fabric so that the edge of the family of angles coincides with the edge of the object. In photo shown below left, for example, a large diffusing fabric was stretched and backlit at an angle to obtain the gradual white-to-gray effect that was desired. For the mirror to be easily identifiable, you need to make sure that it is positioned at the edge of the family of angles. More and more often, however, we see mirrors shown with a clear line between the light and the dark reflections (as in the photo above). To achieve this, use lights with barn doors set up to clearly delineate the difference between the two reflections. This more modern approach is what most manufacturers now prefer. For mirrors, as with all reflective surfaces, you will usually need to avoid hard light sources or lights that are too localized. Instead, you can increase the lighting surface by using either large shapers (octaboxes or umbrellas) or diffusing fabrics. Sometimes both. Another good solution is to aim the light toward a large white wall and then use its reflection to light the mirror. If it is placed far enough away to reveal what needs to be visible, this arrangement provides very even lighting, ideal for a mirror or any surface that produces direct and specular reflections. If you’re trying to produce very segmented lights, alternating between black and white, you can also use barn doors; a black piece of cardboard works just fine. But you should be aware that because of the particular conformation of mirrors, you will not be able to produce a perfectly clean break between the reflection and the unaffected area: there will always be a gray band that appears because of the refraction in the thickness of the glass covering the mirror; the thicker the glass, the wider the band. In product photography, mirrors are often used as a base for the objects being photographed. They make it possible to obtain clearly drawn reflections, which are very useful when the presence of reflections is required. If the glass of the mirror is very thick, a very clear outline will be visible at the base of the object. In fact, the thickness of the glass leaves a small margin of direct reflection in the place where the object is placed, while its reflection appears a little farther away: it’s useless to try to outline it with a pen. Mirrors are also used as reflectors. They are much more efficient than normal photographic reflectors because they reflect about 95% of the light. When you need to set up complex lighting arrangements, or if space is tight, you can always use small mirrors to help you light or unblock one area or another. They are widely used in jewelry photography, where you need to call on a large number of light sources to create light effects on as many facets of the jewelry as possible (for example for precious stones). And finally, as bases for objects to be photographed, mirrors make it possible to provide a faithful accompaniment for the projection of a particular subject (see page 197, backlighting method using a computer screen).LIGHTING A MIRROR

Preparation

Strategy

Light and Barn Doors

Accessory or Base