1

Perspectives and Transitions in Ergonomics

In this chapter, a historical introduction as well as an overview of the present and prospective developments of ergonomics will be given. The aim is to provide an outline for approaching theory building within prospective ergonomics (PE), which in Chapters 2 and 3 will be aligned with ancillary fields of strategic design, innovation, systems and industrial design. To contextualize the work, a range of design approaches, such as systems design, design driven and human/user-centered design, will be introduced with respect to different ergonomic perspectives.

Moreover, this chapter sets the tone for developing the construct of prospection and prospective ergonomics by arguing that this new field of ergonomics is driven by a focus on well-being, by being future oriented and design driven and by the fact that product-service innovation, performance and profit should be sought after within systematically embedded contexts. From this perspective of prospection, the intention is to contextually bring the study of preventive and corrective ergonomics closer to the fields of design and strategic management. Consequences are that with the proliferation of services, human–product interactions and sustainable design, where innovation is usually a concern of many stakeholders, the field of preventive ergonomics is extended to PE and design to strategic design. To conclude this introductory chapter as well as initiate the formation and application of theoretical frameworks, it has been brought forward that pluralism toward the creation of new products and services is a typical trait of PE, which enhances company’s competitive advantage.

1.1. History and definition of ergonomics

Ergonomics is the scientific discipline investigating the interaction between humans and artifacts and the design of systems where people participate. It applies systematic methods and knowledge about people to evaluate and approve the interactions between individuals, technology and organizations at work and during leisure. The purpose of design activities is to match systems, jobs, products and environments to the physical and mental abilities and limitations of people [HEL 97]. The aim is to create a working environment (as far as possible) that contributes to achieving healthy, effective and safe operations.

The study of ergonomics (Gr. ergon + nomos) was originally defined and proposed by the Polish scientist Jastrzebowski in 1857, as a scientific discipline with a very broad scope and a comprehensive range of interests and applications, encompassing each human activity, including labor, entertainment, reasoning and dedication [KAR 05]. A historical overview of ergonomics will be presented in the textbox below to make certain events explicit, where business strategies, the design of products and services, and different ergonomic interventions connect. The historical timeline indicates that ergonomics has engaged in systemic ways of strategizing as early as the beginning of 20th Century ergonomics. However, only in the past 25 years has ergonomics gained acceptance among business managers.

According to Perrow [PER 83], the problem of ergonomics is that too few ergonomists work in companies, that they have no control over budgets and people, and that they are seen solely as protectors of workers, rather than creators of products, systems and services. Presently, the value of ergonomics extends beyond occupational health and safety and related legislation. While maintaining health and safety of consumers and workers, ergonomics has become more valuable in supporting company’s business strategies to stay competitive. This has led to the acceptance of the following broader definition of ergonomics:

- – ergonomics (or human factors) is a scientific discipline, which aims to develop an understanding about the interaction between humans and other system elements. Furthermore, the profession applies theory, principles, data and design methods to optimize human well-being and overall system performance [IEA 00];

- – compared to Jastrzebowski’s definition, the field of ergonomics has become more proactive with respect to problem solving, design, functional usability and the planning of innovative products and services [ROB 09]. Given this emphasis on ergonomics, the link between business strategies and ergonomics is being established through their common interest in creating and designing improved or new products. Companies are increasingly aware that innovation is essential for maintaining a competitive advantage. As all innovations start with a creative idea [AMA 96], which is both novel and suited to the context of the task [BON 09], it has been acknowledged that end-users of products and services can be important resources for product design and innovation [KRI 02, VON 86]. Within the traditions of preventive ergonomics, user involvement is considered essential for the development of user-friendly product and services, and the participatory design methods and tools that have been developed could be useful for linking ergonomics with product and service innovation.

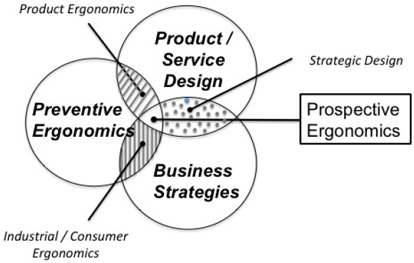

Figure 1.1. Interaction among product and service design, business strategies and preventive ergonomics toward prospective ergonomics

Nowadays ergonomics in industry has the dual purpose of promoting both productivity and “well-being” during and related to working conditions. The continuous search for an optimized balance between productivity and favorable working conditions has given rise to a relatively new type of ergonomics, which is “prospective ergonomics”. The focus of this work is to promote a “prospective turn” to ergonomics as an important feature in strategy formulation and innovation. This means that attention to PE and strategic design can be an important element of how a company realizes its competitive advantage. Figure 1.1 depicts how the interaction between product and service design, business strategies and preventive ergonomics as an emergent field of ergonomics, namely PE, could be envisioned. Consequently, PE redefines the ergonomic profession to be more design and business oriented. However, with its original focus on human well-being and anticipation of hidden future needs, the business orientation of PE is pluralistic rather than being purely driven by performance and profit maximization. In practice, this means that the ergonomist must consider the dynamic context of the firm and understand the different strategic objectives of stakeholders [DUL 09].

1.2. Classification and positioning of ergonomics

Over the past 50 years, ergonomics has evolved as a unique and independent discipline that focuses on the nature of human–artifact interactions, and made connections with engineering, design, technology and management from a science perspective. Within a systemic human–artifact relationship, a variety of natural and artificial products, processes and living environments are emphasized [KAR 05].

The analysis of poor performance, human errors and accidents due to difficulties faced by the human operator when interacting with objects in specific contexts provided a growing body of evidence to facilitate the understanding of man–machine systems (now human–machine systems) and interactions. This stimulated research by the ergonomic academic and military community which led to further investigations of the interactions between people, equipment and their environments. Accordingly, this has resulted in a substantial body of documented knowledge, methodologies and skills for analyzing and designing interactive systems between humans and their environment [DUL 12]. When defining ergonomics from a practice perspective, ergonomic practitioners continue to improve tasks, jobs, products, technologies, processes, organizations, environments and systems to make them compatible with the needs, abilities and limitations of people through planning, design, implementation, evaluation and redesign [IEA 00].

Contemporary ergonomics shows rapidly expanding application areas, continuing improvements in research methodologies, and increased contributions to fundamental knowledge as well as important applications fulfilling the needs of the society at large and its environment. The environment is usually complex and consists of the physical environment (“things”), the organizational environment (how activities are organized and controlled) and the social environment (other people, culture) [MOR 00, WIL 00, CAR 06]. Fundamental characteristics of contemporary ergonomics are that it takes a systems approach, that it is design driven and that it focuses on two related outcomes: performance and well-being.

Building upon the concept of contemporary ergonomics, a relatively new type of ergonomics, which is “prospective ergonomics (PE)” will be introduced with respect to other areas of ergonomics. In the first instance, a structural and systematic depiction of different classifications of ergonomics is shown in Table 1.1 based upon domain, intervention, focus and specialization. Thereafter, Figure 1.2 will show the positioning of PE as well as its connectivity with strategic and industrial design, and with respect to the other ergonomic interventions.

Table 1.1. Classification of ergonomics according to domain, intervention, focus and specialization

| Domain | Product ergonomics | Industrial ergonomics | ||

| Intervention | Corrective ergonomics | Design ergonomics | Prospective ergonomics | |

| Focus | Microergonomics | Mesoergonomics | Macroergonomics | |

| Specialization | Physical ergonomics | Cognitive ergonomics | Organizational ergonomics | |

1.2.1. Ergonomics classified according to domain

Broadly speaking, the domain of ergonomics can be divided into “Product” and “Industrial”. Product ergonomics is a subset of ergonomics, which addresses people’s interaction with products, systems and processes. The emphasis within product ergonomics is to ensure that designs complement the strengths and abilities of people to minimize the effects of their limitations. As a result of this, it becomes necessary to understand variabilities represented in the populations, with respect to age, size, strength, cognitive ability, prior experience, cultural expectations and goals.

Researchers and practitioners study how people, on a daily basis, interact with products, processes and environments to make them safer, more comfortable, easier to use and more efficient. They apply relevant research on biomechanical, physiological and cognitive aspects and juxtapose them with knowledge and understanding of the users and their experiences (Human Factors and Ergonomics: hfes.org, website accessed 2014).

Industrial ergonomics analyzes information about people, job tasks, equipment and workplace design to assist employers in generating a safe and productive environment for their employees. They emphasize the adaptation of job tasks to human ability within work settings such as those found in manufacturing, engineering and construction. On a more formal note, research encompasses how ergonomics influences or is influenced by job design, health and safety management, training, automation and process optimization, etc. [LUS 14].

1.2.2. Ergonomics classified according to intervention

With respect to intervention, corrective, preventive and prospective ergonomics are topics that will be discussed in this section. De Montmollin [DE 67] has categorized ergonomics into corrective ergonomics and preventive/design ergonomics. The former is about correcting existing artifacts, and the latter deals with systems that do not yet exist. According to Laurig [LAU 86], “corrective ergonomics” is associated with traditional ergonomics and is described as developing “corrections through scientific studies”. In this context, “developing corrections” refers to situations where the ergonomist or designer makes user and functional improvements to existing products, systems or processes in a reactive manner; in other words: “redesigning”.

Furthermore, Robert and Brangier [ROB 09] have mapped out the differences and similarities among corrective, preventive/design and prospective ergonomics. Comparisons across the three subsets of interventions, which are interesting when aligned with a similar comparison within design and strategic design later on, are:

- – nature of work and intervention with respect to temporality and expected outcomes;

- – main focus and starting point for human factors activities;

- – implications for research and data collection.

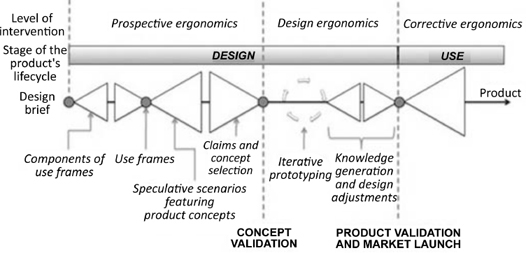

Nelson et al. [NEL 12] proposed aligning the product development process with different ergonomic interventions, as shown in Figure 1.2. Developed around speculative scenario building, PE is strongly compared with framing “use” based on a given design brief. From this prospective ergonomic perspective, scenarios are intended to assist decision making at three main stages in the design process [ROS 02]: (1) the analysis of problem situations in the start of the process, (2) the generation of design solutions at various levels of complexity and (3) the evaluation of these design decisions according to User-centered Design (UCD) criteria. In this context, it can be argued that the purpose of scenarios in the early stages of design is not only to provide an accurate vision of future user activity, but also to crystallize designers’ current knowledge and assumptions about future activity. Thus, from this point of view, scenarios of future use in PE are not just a material for analysis, but also a product of creative design [NEL 14]. However, there is ample potential to implement PE thinking much earlier in the design process. For instance, from a strategic design perspective, PE can be introduced in the Fuzzy-Front-End of Innovation to intervene in product planning and goal finding activities, where future product and/or service proposals are sought after.

Figure 1.2. Alignment of the product development process with different ergonomic interventions (adopted from [NEL 12, p. 9])

1.2.3. Ergonomics classified according to focus

In terms of “focus”, ergonomics can be classified into micro-, meso- and macroergonomics. Macroergonomics can be perceived as a top-down approach to study sociotechnical developments respective to the design and application of an overall work system involving human–job, human–machine and human–software interfaces [HEN 86, HEN 01]. Dray [DRA 85] defines macroergonomics as a three-generation paradigm: (1) user–machine interface, (2) group–technology interface and (3) organization–technology interface.

This top-down approach implies a transient relationship between macro and microergonomics. The first two paradigms are mainly aligned with microergonomics, whereas “organization–technology interface” is typically a phenomenon to be addressed by macroergonomics. Hereby, the concept of human–centeredness is being emphasized, as the worker’s professional and psychosocial characteristics are being considered in the design of a work system. Subsequently, the work system design is being realized through the ergonomic design of specific jobs and related hardware and software interfaces [ROB 01]. Integral to this human-centred design process is the humanized task approach in allocating functions and tasks to collaborative design of technical and personnel subsystems. At an organization-technology interface level, participatory ergonomics is a primary methodology of macroergonomics involving employees at all organizational levels in the design process [IMA 86].

Effective macroergonomic design drives several aspects of the microergonomic design of the work system and makes sure that system components are properly aligned and compatible with the work system’s overall structure. This sociotechnical approach enables technical and personnel subsystems to be jointly optimized from top to bottom throughout the organization as well as harmonized with the work system’s elements and external environments [HEN 91]. When overarching systems, subsystems and system elements are properly aligned and coordinated, it may lead to increased productivity, better quality and improved employee safety, well-being and health, such as psychosocial comfort, motivation and perceived quality of work life [ROB 01].

With respect to complex human–machine systems as well as sociotechnical system concepts, Emery and Trist [EME 60] perceive organizations as open systems, engaged in transforming inputs into desired outputs, and whose permeable boundaries are exposed to the environments in which they exist and upon which they are dependent for their survival. This management perspective toward different orientations of innovation, use of methods, practices and value creation forms the context for strategic design and prospective ergonomic thinking, involving various communities and stakeholders. In other words, the issue of permeability, which concerns unrestricted transfer of knowledge and practices across different levels of value creation, provides interesting avenues for the development of reasoning approaches, processes, methods and tools, which can be applied in PE and strategic design.

1.2.4. Ergonomics classified according to specialization

Traditionally, specialization within ergonomics can be classified according to physical, cognitive and organizational ergonomics. Physical ergonomics is primarily concerned with the human anatomy, studying anthropometric, physiological and biomechanical characteristics related to physical activities [CHA 93, PHE 86, KRO 94, KAR 99, NRC 01]. In cognitive ergonomics, mental processes such as perception, memory, information processing, reasoning and motoric response are a focal point of study, because they are instrumental in determining interactions between humans and ancillary system elements [VIC 99, HOL 03, DIA 04]. Organizational ergonomics, which is similar to macroergonomics, deals with how organizational structures, policies and processes can be optimized within the context of sociotechnical systems [REA 99, HOL 03, NEM 04]. The optimization of human well-being, and overall systems performance, includes the following topics: communication, crew resource management, design of working times, teamwork, participatory work design, community ergonomics, computer-supported cooperative work, new work paradigms, virtual organizations, telework and quality management [KAR 98].

To conclude this chapter, the various ways one is able to classify human factors show that the field has advanced significantly. According to Norman [NOR 10], “The field of Human Factors and its many descendants – Cognitive Engineering, Human-Computer Interaction, Cognitive Ergonomics, Human-Systems Integration, etc. – has made numerous, wonderful advances in the many decades since the enterprise began”. However, the discipline still serves many to rescue rather than to create. “It is time for a change”.

1.3. A systems approach in ergonomics

According to Merriam Webster, a system is an integrated compilation of interacting and interdependent components (accessed October 7, 2015). Within the context of ergonomics, adopting a system- and design-driven approach in the development of products and services establishes a broader understanding of how a strategic prospective ergonomic approach contributes to performance, well-being and stakeholder involvement [DUL 12].

Ergonomics focuses on the design of these systems consisting of humans and their environment [HEL 97, SCH 09]. The system consists of the human-made elements, for example (work)places, tools, products, technical processes, services, software, built environments, tasks and organizations as well as other humans [WIL 00]. An ergonomic system approach addresses issues on various levels: micro, meso and macro. A microergonomic system approach level is concerned with how humans use tools or perform single tasks, whereas at a mesolevel, humans are considered a part of technical processes or organizations. At a macrolevel, humans are perceived as an element in networks of organizations, regions, countries or the world [RAS 00, DUL 12].

This interdisciplinary systems approach, which has its roots in engineering, is becoming even more important, when ergonomic expertise is redirected to discover prospective hidden needs of various user populations and stakeholders. Furthermore, as positivistic inclined systems engineers advocate the application of technical design specifications as the true basis for the product design, ergonomists’ expertise complements such systems approaches from a human-centered perspective to directly impact the work of the design and development team as well as the final design of the product. To be more specific, impact can occur from a hardware ergonomic perspective, software ergonomic perspective, environmental ergonomic perspective and macroergonomic perspective [SAM 05]. This implies that when engineers, designers and ergonomists define problems and formulate solutions within the broader context of the human in a prospective context, system boundaries need to be clearly defined, and be more focused on people specific aspects (e.g. only physical), specific aspects of the environment (e.g. only workplace) or a specific level (e.g. micro).

1.4. Design-driven versus a human-centered approach

In the design process, micro-, meso- and macrolevel ergonomics should be understood from a human component perspective, covering individual, collective and social aspects. Given these foci, ergonomic specialists and interpreters [VER 08] are expected to become more actively involved in creation processes, particularly with respect to the design of product service systems (PSS). Furthermore, actors, who will be part of the system being designed, are often brought into the development process as participants [NOR 91]. All stakeholders’ insights and competencies regarding methods for designing and assessing technical and organizational environments, analyzing and acting on situations, and methods for organizing and managing participatory approaches are invaluable for continuously improving PSS [WOO 00].

With respect to PE, designers, ergonomist and participative users should adopt an integrative role in collective design decision making with other contributors and stakeholders of design [RAS 00] based on their knowledge, activities, needs and skills. Furthermore, in the process of analyzing, contextualizing and managing design problems, PE has the legitimacy to stimulate and moderate design processes by, for instance, translating engineering terminology or concepts to end-user terminologies and vice versa.

1.5. Focus on performance and well-being

Three related system outcomes can be achieved by fitting the environment to the human: well-being (e.g. health and safety, pleasure, learning, personal satisfaction and development), performance (e.g. productivity, efficiency, effectiveness, quality, innovativeness, flexibility, systems) and safety (security, reliability, sustainability). Especially within the context of PE and strategic design, it is a challenge for ergonomists to balance multiple outcomes, such as well-being, exposure to learning and profit maximization. In other words, ergonomists need to manage practical implications and ethical trade-offs within systems [WIL 09], considering short- and long-term interdependency between performance and well-being.

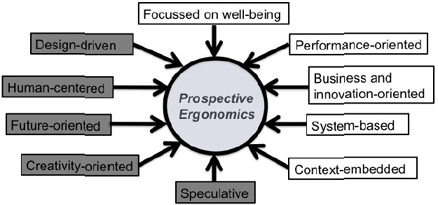

This interdependency between performance and well-being is an issue that needs to be aligned1 with strategic business principles. Once aligned and understood, looking at prospection can advance a proactive design approach within ergonomics. In other words, the expansion from traditional to contemporary ergonomics has promoted the concept of “prospection” and introduced a new framework for structuring ergonomic activities around corrective, preventive (design) and PE [BRA 10, ROB 12]. The latter looks forward in time defining human needs and activities to create human-centered artifacts that besides their usefulness provide positive user experiences. Figure 1.3 shows the various dimensions determining PE, which extend beyond well-being, productivity and a system approach. It stresses the importance of being future oriented, pluralistic and emphasizes that innovative design solutions are systemically embedded in context.

Figure 1.3. Dimensions in white apply to general ergonomics. Dimensions highlighted in gray specifically apply to PE

All facets of ergonomics carry elements of prospection. The concept of prospection also brings ergonomics, which mainly engages in addressing preventive and corrective human machine issues in certain contextual settings, closer to the field of design. Furthermore, with the proliferation of service, interaction and sustainable design, where innovation is usually a concern of many stakeholders, the field of ergonomics is extended to PE and design to strategic design. As shown in Figure 1.3, “design driven”, “human centered”, “creativity-oriented”, “future-oriented” and “speculative” are typical dimensions, which have been adopted from design.