Chapter 7. Monitoring and Logging

When Noah worked in startups in San Francisco, he used his lunch break to exercise. He would play basketball, run up to Coit Tower, or practice Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. Most of the startups Noah worked at would have a catered lunch.

He discovered a very unusual pattern coming back from lunch. There was never anything unhealthy left to eat. The leftovers were often full salads, fruit, vegetables, or healthy lean meats. The hordes of startup workers ate all of the unhealthy options while he was exercising, leaving zero temptation to eat bad food. There is something to be said for not following the crowd.

Likewise, the easy path is to ignore operations when developing machine learning models, mobile apps, and web apps. Ignoring operations is so typical it is like eating the chips, soda, and ice cream at the catered lunch. Being normal isn’t necessarily preferred, though. In this chapter, the “salad and lean meats” approach to software development is described.

Key Concepts in Building Reliable Systems

Having built companies for a while, it’s fun to look at what worked on the software engineering portion versus what didn’t. One of the best antipatterns out there is “trust me.” Any sane DevOps professional will not trust humans. They are flawed, make emotional mistakes, and can destroy entire companies on a whim. Especially if they are the company’s founder.

Instead of a hierarchy based on complete nonsense, a better approach to building reliable systems is to build them piece by piece. In additional, when creating the platform, failure should be expected regularly. The only thing that will affect this truism is if a powerful person is involved in building the architecture. In that case, this truism will be exponentially increased.

You may have heard of the chaos monkey from Netflix, but why bother with that? Instead, let the founders of your company, the CTO, or the VP of Engineering do drive-by coding and second-guess your architecture and codebase. The human chaos monkey will run circles around Netflix. Better yet, let them compile jar files in the middle of production outages and put them on nodes one by one, via SSH, all the while yelling, “This will do the trick!” In this way, the harmonic mean of chaos and ego is achieved.

What is the action item for a sane DevOps professional? Automation is greater than hierarchy. The only solution to the chaos of startups is automation, skepticism, humility, and immutable DevOps principles.

Immutable DevOps Principles

It is hard to imagine a better place to start to build a reliable system than this immutable principle. If the CTO is building Java .jar files from a laptop to fix production fires, you should just quit your job. There is nothing that will save your company. We should know—we’ve been there!

No matter how smart/powerful/charismatic/creative/rich a person is, if they are manually applying critical changes in a crisis to your software platform, you are already dead. You just don’t know it yet. The alternative to this monstrous existence is automation.

Humans cannot be involved in deploying software in the long term. This is the #1 antipattern that exists in the software industry. It is essentially a back door for hooligans to wreak havoc on your platform. Instead, deploying software, testing software, and building software needs to be 100% automated.

The most significant initial impact you can have in a company is to set up continuous integration and continuous delivery. Everything else pales in comparison.

Centralized Logging

Logging follows close behind automation in importance. In large-scale, distributed systems, logging isn’t optional. Special attention must be paid to logging at both the application level and the environment level.

For example, exceptions should always be sent to the centralized logging system. On the other hand, while developing software, it is often a good idea to create debug logging instead of print statements. Why do this? Many hours are spent developing heuristics to debug the source code. Why not capture that so it can be turned on if a problem surfaces in production again?

The trick here is logging levels. By creating debug log levels that only appear in the nonproduction environment, it allows the logic of debugging to be kept in the source code. Likewise, instead of having overly verbose logs appear in production and add confusion, they can be toggled on and off.

An example of logging in large-scale distributed systems is what Ceph uses: daemons can have up to 20 debug levels! All of these levels are handled in code, allowing the system to fine-tune the amount of logging. Ceph furthers this strategy by being able to restrict the amount of logging per daemon. The system has a few daemons, and the logging can be increased for one or all of them.

Case Study: Production Database Kills Hard Drives

Another vital strategy for logging is solving scalability. Once the application is large enough, it might not be feasible to store all logs in a file anymore. Alfredo was once tasked to debug a problem with the primary database of an extensive web application that hosted about one hundred newspaper, radio station, and television station sites. These sites generated lots of traffic and produced massive amounts of logs. So much log output was created that the logging for PostgreSQL was set to a minimum, and he couldn’t debug the problem because it required raising the log level. If the log level was raised, the application would stop working from the intense I/O generated. Every day at around five o’clock in the morning, the database load spiked. It had gotten progressively worse.

The database administrators were opposed to raising the log levels to see the most expensive queries (PostgreSQL can include query information in the logs) for a whole day, so we compromised: fifteen minutes at around five o’clock in the morning. As soon as he was able to get those logs, Alfredo immediately got to rate the slowest queries and how often they were run. There was a clear winner: a SELECT * query that was taking so long to complete that the fifteen-minute window was not enough to capture its runtime. The application didn’t do any queries that selected everything from any table; what could it be?

After much persuasion, we got access to the database server. If the spike in load happens at around five o’clock in the morning every single day, is it possible that there is some recurrent script? We looked into crontab (the program that keeps track of what runs at given intervals), which showed a suspicious script: backup.sh. The contents of the script had a few SQL statements that included several SELECT *. The database administrators were using this to back up the primary database, and as the size of the database grew, so did the load until it was no longer tolerable. The solution? Stop using the script, and back up one of the four secondary (replica) databases.

That saved the backup problem, but it didn’t help the inability to have access to logs. Thinking ahead on distributing logging output is the right approach. Tools like rsyslog are meant to solve this, and if added from the start, it can save you from being unable to solve a production outage.

Did You Build It or Buy It?

It is incredible how much vendor lock-in gets press. Vendor lock-in, though, is in the eye of the beholder. You can pretty much throw a rock in any direction in downtown San Francisco and hit someone preaching the evils of vendor lock-in. When you dig a little deeper though, you wonder what their alternative is.

In Economics, there is a principle called comparative advantage. In a nutshell, it means there is an economic benefit to focusing on what you are best at and outsourcing other tasks to other people. With the cloud, in particular, there is continuous improvement, and end-users benefit from that improvement without an aggregated cost—and most of the time with less complexity than before.

Unless your company is operating at the scale of one of the giants in technology, there is almost no way to implement, maintain, and improve a private cloud and be able to save money and improve the business at the same time. For example, in 2017, Amazon released the ability to deploy multimaster databases with automatic failover across multiple Availability Zones. As someone who has attempted this, I can say that it is borderline impossible and tremendously hard to add the ability of automatic failover in such a scenario. One of the golden questions to consider regarding outsourcing is: “Is this a core competency of the business?” A company that runs its own mail server but its core competency is selling car parts is playing with fire and probably already losing money.

Fault Tolerance

Fault tolerance is a fascinating topic but it can be very confusing. What is meant by fault tolerance, and how can you achieve it? A great place to learn more about fault tolerance is to read as many white papers from AWS as you can.

When designing fault-tolerant systems, it’s useful to start by trying to answer the following question: when this service goes down, what can I implement to eliminate (or reduce) manual interaction? Nobody likes getting notifications that a critical system is down, especially when this means numerous steps to recover, even less when it takes communication with other services to ensure everything is back to normal. Note that the question is not being framed as an improbable event, it explicitly acknowledges that the service will go down and that some work will needed done to get it up and running.

A while ago, a full redesign of a complex build system was planned. The build system did several things, most of them related to packaging and releasing the software: dependencies had to be in check, make and other tooling built binaries, RPM and Debian packages were produced, and repositories for different Linux distributions (like CentOS, Debian, and Ubuntu) were created and hosted. The main requirement for this build system was that it had to be fast.

Although speed was one of the primary objectives, when designing a system that involves several steps and different components, it is useful to address the known pain points and try hard to prevent new ones. There are always going to be unknowns in large systems, but using the right strategies for logging (and logging aggregation), monitoring, and recovery are crucial.

Turning our attention back to the build system, one of the problems was that the machines that created the repositories were somewhat complex: an HTTP API received packages for a particular project at a specific version, and repositories were generated automatically. This process involved a database, a RabbitMQ service for asynchronous task handling, and massive amounts of storage to keep repositories around, served by Nginx. Finally, some status reporting would be sent to a central dashboard, so developers could check where in the build process their branch was. It was crucial to design everything around the possibility of this service going down.

A big note was added to the whiteboard that read: “ERROR: the repo service is down because the disk is full.” The task was not necessarily to prevent a disk being full, but to create a system that can continue working with a full disk, and when the problem is solved, almost no effort is required to put it back into the system. The “full disk” error was a fictional one that could’ve been anything, like RabbitMQ not running, or a DNS problem, but exemplified the task at hand perfectly.

It is difficult to understand the importance of monitoring, logging, and sound design patterns until a piece of the puzzle doesn’t work, and it is impossible to determine the why and the how. You need to know why it went down so that prevention steps can be instrumented (alerts, monitoring, and self-recovery) to avoid this problem from repeating itself in the future.

To allow this system to continue to work, we split the load into five machines, all of them equal and doing the same work: creating and hosting repositories. The nodes creating the binaries would query an API for a healthy repo machine, which in turn would send an HTTP request to query the /health/ endpoint of the next build server on its list. If the server reported healthy, the binaries would go there; otherwise, the API would pick the next one on the list. If a node failed a health check three times in a row, it was put out of rotation. All a sysadmin had to do to get it back into rotation after a fix was to restart the repository service. (The repository service had a self-health assessment that if successful would notify the API that it was ready to do work.)

Although the implementation was not bulletproof (work was still needed to get a server up, and notifications weren’t always accurate), it had a tremendous impact on the maintenance of the service when restoration was required, and kept everything still functioning in a degraded state. This is what fault tolerance is all about!

Monitoring

Monitoring is one of those things where one can do almost nothing and still claim that a monitoring system is in place (as an intern, Alfredo once used a curl cronjob to check a production website), but can grow to be so complicated that the production environment seems nimble in comparison. When done right, monitoring and reporting, in general, can help answer the most difficult questions of a production life cycle. It’s crucial to have and difficult to get right. This is why there are many companies that specialize in monitoring, alerting, and metric visualization.

At its core, there are two paradigms most services fall into: pull and push. This chapter will cover Prometheus (pull) and Graphite with StatsD (push). Understanding when one is a better choice than the other, and the caveats, is useful when adding monitoring to environments. Most importantly, it’s practical to know both and have the ability to deploy whichever services that will work best in a given scenario.

Reliable time-series software has to withstand incredibly high rates of incoming transactional information, be able to store that information, correlate it with time, support querying, and offer a graphical interface that can be customized with filters and queries. In essence, it must almost be like a high-performing database, but specific to time, data manipulation, and visualization.

Graphite

Graphite is a data store for numerical time-based data: it keeps numeric information that correlates to the time it was captured and saves it according to customizable rules. It offers a very powerful API that can be queried for information about its data, with time ranges, and also apply functions that can transform or perform computations in data.

An important aspect of Graphite is that it does not collect data; instead, it concentrates on its API and ability to handle immense amounts of data for periods of time. This forces users to think about what collecting software to deploy along with Graphite. There are quite a few options to choose from for shipping metrics over to Graphite; in this chapter we will cover one of those options, StatsD.

Another interesting aspect of Graphite is that although it comes with a web application that can render graphs on demand, it is common to deploy a different service that can use Graphite directly as a backend for graphs. An excellent example of this is the fantastic Grafana project, which provides a fully-featured web application for rendering metrics.

StatsD

Graphite allows you to push metrics to it via TCP or UDP, but using something like StatsD is especially nice because there are instrumentation options in Python that allow workflows such as aggregating metrics over UDP and then shipping them over to Graphite. This type of setup makes sense for Python applications that shouldn’t block to send data over (TCP connections will block until a response is received; UDP will not). If a very time-expensive Python loop is being captured for metrics, it wouldn’t make sense to add the time it takes to communicate to a service that is capturing metrics.

In short, sending metrics to a StatsD service feels like no cost at all (as it should be!). With the Python instrumentation available, measuring everything is very straightforward. Once a StatsD service has enough metrics to ship to Graphite, it will start the process to send the metrics over. All of this occurs in a completely asynchronous fashion, helping the application to continue. Metrics, monitoring, and logging should never impact a production application in any way!

When using StatsD, the data pushed to it is aggregated and flushed to a configurable backend (such as Graphite) at given intervals (which default to 10 seconds). Having deployed a combination of Graphite and StatsD in several production environments, it has been easier to use one StatsD instance on every application server instead of a single instance for all applications. That type of deployment allows more straightforward configuration and tighter security: configuration on all app servers will point to the localhost StatsD service and no external ports will need to be opened. At the end, StatsD will ship the metrics over to Graphite in an outbound UDP connection. This also helps by spreading the load by pushing the scalability further down the pipeline into Graphite.

Note

StatsD is a Node.js daemon, so installing it means pulling in the Node.js dependency. It is certainly not a Python project!

Prometheus

In a lot of ways, Prometheus is very similar to Graphite (powerful queries and visualization). The main difference is that it pulls information from sources, and it does this over HTTP. This requires services to expose HTTP endpoints to allow Prometheus to gather metric data. Another significant difference from Graphite is that it has baked-in alerting, where rules can be configured to trigger alerts or make use of the Alertmanager: a component in charge of dealing with alerts, silencing them, aggregating them, and relaying them to different systems such as email, chat, and on-call platforms.

Some projects like Ceph already have configurable options to enable Prometheus to scrape information at specific intervals. It’s great when this type of integration is offered out of the box; otherwise, it requires running an HTTP instance somewhere that can expose metric data for a service. For example, in the case of the PostgreSQL database, the Prometheus exporter is a container that runs an HTTP service exposing data. This might be fine in a lot of cases, but if there are already integrations to gather data with something, such as collectd, then running HTTP services might not work that well.

Prometheus is a great choice for short-lived data or time data that frequently changes, whereas Graphite is better suited for long-term historical information. Both offer a very advanced query language, but Prometheus is more powerful.

For Python, the prometheus_client is an excellent utility to start shipping metrics over to Prometheus; if the application is already web-based, the client has integrations for lots of different Python webservers, such as Twisted, WSGI, Flask, and even Gunicorn. Aside from that, it can also export all its data to expose it directly at a defined endpoint (versus doing it on a separate HTTP instance). If you want your web application exposing in /metrics/, then adding a handler that calls prometheus_client.generate_latest() will return the contents in the format that the Prometheus parser understands.

Create a small Flask application (save it to web.py) to get an idea how simple generate_latest() is to use, and make sure to install the prometheus_client package:

fromflaskimportResponse,Flaskimportprometheus_clientapp=Flask('prometheus-app')@app.route('/metrics/')defmetrics():returnResponse(prometheus_client.generate_latest(),mimetype='text/plain; version=0.0.4; charset=utf-8')

Run the app with the development server:

$ FLASK_APP=web.py flask run * Serving Flask app "web.py" * Environment: production WARNING: This is a development server. Use a production WSGI server instead. * Running on http://127.0.0.1:5000/ (Press CTRL+C to quit) 127.0.0.1 - - [07/Jul/2019 10:16:20] "GET /metrics HTTP/1.1" 308 - 127.0.0.1 - - [07/Jul/2019 10:16:20] "GET /metrics/ HTTP/1.1" 200 -

While the application is running, open a web browser and type in the URL http://localhost:5000/metrics. It starts generating output that Prometheus can collect, even if there is nothing really significant:

... # HELP process_cpu_seconds_total Total user and system CPU time in seconds. # TYPE process_cpu_seconds_total counter process_cpu_seconds_total 0.27 # HELP process_open_fds Number of open file descriptors. # TYPE process_open_fds gauge process_open_fds 6.0 # HELP process_max_fds Maximum number of open file descriptors. # TYPE process_max_fds gauge process_max_fds 1024.0

Most production-grade web servers like Nginx and Apache can produce extensive metrics on response times and latency. For example, if adding that type of metric data to a Flask application, the middleware, where all requests can get recorded, would be a good fit. Apps will usually do other interesting things in a request, so let’s add two more endpoints—one with a counter, and the other with a timer. These two new endpoints will generate metrics that will get processed by the prometheus_client library and reported when the /metrics/ endpoint gets requested over HTTP.

Adding a counter to our small app involves a couple of small changes. Create a new index endpoint:

@app.route('/')defindex():return'<h1>Development Prometheus-backed Flask App</h1>'

Now define the Counter object. Add the name of the counter (requests), a short description (Application Request Count), and at least one useful label (such as endpoint). This label will help identify where this counter is coming from:

fromprometheus_clientimportCounterREQUESTS=Counter('requests','Application Request Count',['endpoint'])@app.route('/')defindex():REQUESTS.labels(endpoint='/').inc()return'<h1>Development Prometheus-backed Flask App</h1>'

With the REQUESTS counter defined, include it in the index() function, restart the application, and make a couple of requests. If /metrics/ is then requested, the output should show some new activity we’ve created:

...

# HELP requests_total Application Request Count

# TYPE requests_total counter

requests_total{endpoint="/"} 3.0

# TYPE requests_created gauge

requests_created{endpoint="/"} 1.562512871203272e+09

Now add a Histogram object to capture details on an endpoint that sometimes takes a bit longer to reply. The code simulated this by sleeping for a randomized amount of time. Just like the index function, a new endpoint is needed as well, where the Histogram object is used:

fromprometheus_clientimportHistogramTIMER=Histogram('slow','Slow Requests',['endpoint'])

The simulated expensive operation will use a function that tracks the start time and end time and then passes that information to the histogram object:

importtimeimportrandom@app.route('/database/')defdatabase():withTIMER.labels('/database').time():# simulated database response timesleep(random.uniform(1,3))return'<h1>Completed expensive database operation</h1>'

Two new modules are needed: time and random. Those will help calculate the time passed onto the histogram and simulate the expensive operation being performed in the database. Running the application once again and requesting the /database/ endpoint will start producing content when /metrics/ is polled. Several items that are measuring our simulation times should now appear:

# HELP slow Slow Requests

# TYPE slow histogram

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.005"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.01"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.025"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.05"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.075"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.1"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.25"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.5"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="0.75"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="1.0"} 0.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="2.5"} 2.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="5.0"} 2.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="7.5"} 2.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="10.0"} 2.0

slow_bucket{endpoint="/database",le="+Inf"} 2.0

slow_count{endpoint="/database"} 2.0

slow_sum{endpoint="/database"} 2.0021886825561523

The Histogram object is flexible enough that it can operate as a context manager, a decorator, or take in values directly. Having this flexibility is incredibly powerful and helps produce instrumentation that can work in most environments with little effort.

Instrumentation

At a company we are familiar with, there was this massive application that was used by several different newspapers—a giant monolithic web application that had no runtime monitoring. The ops team was doing a great job keeping an eye on system resources such as memory and CPU usage, but there was nothing checking how many API calls per second were going to the third-party video vendor, and how expensive these calls were. One could argue that that type of measurement is achievable with logging, and that wouldn’t be wrong, but again, this is a massive monolithic application with absurd amounts of logging already.

The question here was how to introduce robust metrics with easy visualization and querying that wouldn’t take three days of implementation training for developers and make it as easy as adding a logging statement in the code. Instrumentation of any technology at runtime has to be as close to the previous statement as possible. Any solution that drifts from that premise will have trouble being successful. If it is hard to query and visualize, then few people will care or pay attention. If it is hard to implement (and maintain!), then it might get dropped. If it is cumbersome for developers to add at runtime, then it doesn’t matter if all the infrastructure and services are ready to receive metrics; nothing will get shipped over (or at least, nothing meaningful).

The python-statsd is an excellent (and tiny) library that pushes metrics over to StatsD (which later can be relayed to Graphite) and can help you understand how metrics can be instrumented easily. Having a dedicated module in an application that wraps the library is useful, because you will need to add customization that would become tedious if repeated everywhere.

Tip

The Python client for StatsD has a few packages available on PyPI. For the purposes of these examples, use the python-statsd package. Install it in a virtual environment with pip install python-statsd. Failing to use the right client might cause import errors!

One of the simplest use cases is a counter, and the examples for python-statsd show something similar to this:

>>>importstatsd>>>>>>counter=statsd.Counter('app')>>>counter+=1

This example assumes a StatsD is running locally. Therefore there is no need to create a connection; the defaults work great here. But the call to the Counter class is passing a name (app) that will not work in a production environment. As described in “Naming Conventions”, it is crucial to have a good scheme that helps identify environments and locations of the stats, but it would be very repetitive if you had to do this everywhere. In some Graphite environments, a secret has to prefix the namespace on all metrics being sent as a means of authentication. This adds another layer that needs to be abstracted away so that it isn’t needed when instrumenting metrics.

Some parts of the namespace, such as the secret, have to be configurable, and others can be programmatically assigned. Assuming there is a way to optionally prefix the namespace with a function called get_prefix(), this is how the Counter would get wrapped to provide a smooth interaction in a separate module. For the examples to work, create the new module, name it metrics.py, and add the following:

importstatsdimportget_prefixdefCounter(name):returnstatsd.Counter("%s.%s"%(get_prefix(),name))

By following the same example used in “Naming Conventions” for a small Python application that calls to the Amazon S3 API in a path such as web/api/aws.py, the Counter can get instantiated like this:

frommetricsimportCountercounter=Counter(__name__)counter+=1

By using __name__, the Counter object is created with the full Python namespace of the module that will appear on the receiving side as web.api.aws.Counter. This works nicely, but it isn’t flexible enough if we need more than one counter in loops that happen in different places. We must modify the wrapper so that a suffix is allowed:

importstatsdimportget_prefixdefCounter(name,suffix=None):ifsuffix:name_parts=name.split('.')name_parts.append(suffix)name='.'.join(name_parts)returnstatsd.Counter("%s.%s"%(get_prefix(),name))

If the aws.py file contains two places that require a counter, say a read and a write function for S3, then we can easily suffix them:

frommetricsimportCounterimportbotodefs3_write(bucket,filename):counter=Counter(__name__,'s3.write')conn=boto.connect_s3()bucket=conn.get_bucket(bucket)key=boto.s3.key.Key(bucket,filename)withopen(filename)asf:key.send_file(f)counter+=1defs3_read(bucket,filename):counter=Counter(__name__,'s3.read')conn=boto.connect_s3()bucket=conn.get_bucket(bucket)k=Key(bucket)k.key=filenamecounter+=1returnk

These two helpers now have unique counters from the same wrapper, and if configured in a production environment, the metrics appear in a namespace similar to secret.app1.web.api.aws.s3.write.Counter. This level of granularity is helpful when trying to identify metrics per operation. Even if there are cases where granularity isn’t needed, it is always better to have it and ignore it than to need it and not have it. Most metric dashboards allow customization for grouping metrics.

The suffix is useful when added to function names (or class methods) that hardly represent what they are or what they do, so improving the naming by using something meaningful is another benefit to this added flexibility:

defhelper_for_expensive_operations_on_large_files():counter=Counter(__name__,suffix='large_file_operations')whileslow_operation:...counter+=1

Note

Counters and other metric types such as gauges can be so easy to add that it might be tempting to include them in a loop, but for performance-critical code blocks that run thousands of times per second, it might be impactful to add these types of instrumentation. Limiting the metrics that are being sent or sending them later are good options to consider.

This section showed how to instrument metrics for a local StatsD service. This instance will end up relaying its metric data to a configured backend like Graphite, but these simplistic examples aren’t meant to be a StatsD-only solution. To the contrary, they demonstrate that adding helpers and utilities to wrap common usage is a must, and when easy instrumentation exists, developers will want to add it everywhere. The problem of having too much metric data is preferable to having no metrics at all.

Naming Conventions

In most monitoring and metric services such as Graphite, Grafana, Prometheus, and even StatsD, there is a notion of namespaces. Namespaces are very important, and it is worth thinking carefully on a convention that will allow easy identification of system components, while at the same time allow enough flexibility to accommodate for growth or even change. These namespaces are similar to how Python uses them: a dot separates each name, and each separated part represents a step in a hierarchy from left to right. The first item from the left is the parent, and every subsequent part is a child.

For example, let’s assume we have some API calls to AWS in a nimble Python application that serves images on a website. The Python module where we have the spot we want metrics is in a path like this: web/api/aws.py. The natural namespace choice for this path could be: web.api.aws, but what if we have more than one production app server? Once the metrics ship with one namespace, it’s hard (almost impossible!) to change to a different scheme. Let’s improve the namespace to help identify production servers: {server_name}.web.api.aws

Much better! But can you see another issue? When shipping metrics, a trailing name is sent over. In the case of counters example, the name would be something like: {server_name}.web.api.aws.counter. That is a problem because our little application does several calls to AWS like S3 and we may want to talk to other AWS services in the future. It is easier to fix child naming than parent naming, so in this case, it just requires developers to match metrics as granularly as possible to what is measured. For example, if we had an S3 module inside the aws.py file, it would make sense to include it to distinguish it from other pieces. The child portion of that metric would look like aws.s3, and a counter metric would end up looking like aws.s3.counter.

Having so many variables for namespaces can feel cumbersome, but most established metric services allow easy combinations, such as “show me count average for all S3 calls last week but only from production servers in the East Coast.” Pretty powerful, huh?

There is another potential issue here. What do we do with production and staging environments? What if I’m developing and testing in a virtual machine somewhere? The {server_name} part might not help much here if everyone calls their development machine srv1. If deploying to different regions, or even if there is a plan to scale beyond a single region or country, an extra addition to the namespace can make sense as well. There are numerous ways to expand on namespaces to better fit an environment, but something like this is a suitable prefix: {region}.{prod|staging|dev}.{server_name}

Logging

It can be daunting to configure logging in Python correctly. The logging module is very performant and has several different outlets that can receive its output. Once you grasp its initial configuration, it isn’t that complicated to add to it. We’ve been guilty of rewriting an alternative way of logging because of the dislike for configuring the logging module properly. This was a mistake, because it almost never accounted for all the things that the standard library module does well: multithreaded environments, unicode, and supporting multiple destinations other than STDOUT, just to name a few.

Python’s logging module is so big and can be made to accommodate so many different uses (just like almost all software in this very distilled chapter), that not even a whole chapter would be sufficient to cover it all. This section will offer short examples for the simplest use cases, and then move progressively toward more complex uses. Once a few scenarios are well understood, it isn’t hard to keep expanding logging into other configurations.

Even though it is complex and can take some time to fully comprehend, it is one of the crucial pillars of DevOps. You cannot be a successful DevOps person without it.

Why Is It Hard?

Python applications, like command-line tools and one-shot types of tools, usually have a top-to-bottom design and are very procedural. When you start learning development with something like Python (or perhaps Bash), it is reasonable to get used to that flow. Even when moving to more object-oriented programming and using more classes and modules, there is still this sense of declaring what you need, instantiating objects to use them, and so on. Modules and objects aren’t usually preconfigured at import time, and it is not common to see some imported module be configured globally for the whole project even before being instantiated.

There is this sense of “somehow this is configured and how is it possible if I haven’t even called it yet.” Logging is like that; once configured at runtime, the module somehow persists this configuration regardless of where it is imported and used, and before creating loggers. This is all very convenient, but it is hard to get used to when almost nothing else works this way in the Python standard library!

The basicconfig

The easiest way out of logging configuration misery is to simply use basicconfig. It is a straightforward way to get logging working, with lots of defaults and about three lines worth of work:

>>>importlogging>>>logging.basicConfig()>>>logger=logging.getLogger()>>>logger.critical("this can't be that easy")CRITICAL:root:thiscan't be that easy

With almost no need to understand anything about logging, messages appear and the module appears to be configured correctly. It is also good that it can support more customization and a few options that are well-suited for small applications that don’t need highly customized logging interfaces. The format of the log messages and setting the verbosity are achieved with ease:

>>>importlogging>>>FORMAT='%(asctime)s%(name)s%(levelname)s%(message)s'>>>logging.basicConfig(format=FORMAT,level=logging.INFO)>>>logger=logging.getLogger()>>>logger.debug('this will probably not show up')>>>logger.warning('warning is above info, should appear')2019-07-0808:31:08,493rootWARNINGwarningisaboveinfo,shouldappear

This example was configured to set the minimum level at INFO, which is why the debug message didn’t emit anything. Formatting was passed into the basicConfig call to set the time, the name of the logging (more on that later in this section), the level name, and finally, the message. That is plenty for most applications, and it is good to know that a simple entry into logging can do so much already.

The problem with this type of configuration is that it will not be sufficient to take advantage of more complex scenarios. This configuration has a lot of defaults that might not be acceptable and will be cumbersome to change. If there is any possibility that the application will need something a bit more complicated, it is recommended to fully configure logging and go through the pain of understanding how to do that.

Deeper Configuration

The logging module has several different loggers; these loggers can be configured independently, and they can also inherit configuration from a parent logger. The top-most logger is the root logger, and all other loggers are child loggers (root is the parent). When configuring the root logger, you are essentially setting the configuration for everything globally. This way of organizing logging makes sense when different applications or different parts of a single application require different types of logging interfaces and settings.

If a web application wants to send WSGI server errors over email but log everything else to a file, this would be impossible to do if a single root-level logger was being configured. This is similar to “Naming Conventions” in that the names are separated by dots, and every dot indicates a new child level. It means that app.wsgi could be configured to send error logs over email, while app.requests can be set separately with file-based logging.

Tip

A nice way of dealing with this namespace is by using the same namespace as Python instead of using something custom. Do this by using name to create loggers in modules. Using the same namespace for both the project and logging prevents confusion.

Configuration of logging should be set as early as possible. If the application is a command-line tool, then the right place for it is at the main entry point, probably even before parsing arguments. For web applications, the logging configuration is usually through the framework’s helpers. Most popular web frameworks today have a facility for logging configuration: Django, Flask, Pecan, and Pyramid all offer an interface for early logging configuration. Take advantage of it!

This example shows how to configure a command-line tool; you can see that there are a few similarities to basicConfig:

importloggingimportosBASE_FORMAT="[%(name)s][%(levelname)-6s]%(message)s"FILE_FORMAT="[%(asctime)s]"+BASE_FORMATroot_logger=logging.getLogger()root_logger.setLevel(logging.DEBUG)try:file_logger=logging.FileHandler('application.log')except(OSError,IOError):file_logger=logging.FileHandler('/tmp/application.log')file_logger.setLevel(logging.INFO)console_logger.setFormatter(logging.Formatter(BASE_FORMAT))root_logger.addHandler(file_logger)

A lot is happening here. The root logger is requested by calling getLogger() without any arguments, and the level is set at DEBUG. This is a good default to have, since other child loggers can modify the level. Next, the file logger gets configured. In this case, it tries to create the file logger that will fall back to a temporary location if it can’t write to it. It then gets set at the INFO level, and its message format is changed to include a timestamp (useful for file-based log files).

Note how at the end, the file logger gets added to the root_logger. It feels counter-intuitive, but in this case, the root configuration is being set to handle everything. Adding a stream handler to the root logger will make the application send logs to both the file and standard error at the same time:

console_logger=logging.StreamHandler()console_logger.setFormatter(BASE_FORMAT)console_logger.setLevel(logging.WARNING)root_logger.addHandler(console_logger)

In this case, the BASE_FORMAT was used, because it’s going to the terminal, where timestamps can cause excessive noise. As you can see, it takes quite a bit of configuration and settings, and it gets very complicated once we start dealing with different loggers. To minimize this, a separate module with a helper that sets all these options is preferable. As an alternative to this type of configuration, the logging module offers a dictionary-based configuration, where the settings are set in a key-value interface. The example below shows how the configuration would look for the same example.

To see it in action, add a couple of log calls at the end of the file, execute directly with Python, and save it in a file called log_test.py:

# root loggerlogger=logging.getLogger()logger.warning('this is an info message from the root logger')app_logger=logging.getLogger('my-app')app_logger.warning('an info message from my-app')

The root logger is the parent, and a new logger called my-app is introduced. Executing the file directly gives output in the terminal as well as in a file called application.log:

$ python log_test.py [root][WARNING] this is an info message from the root logger [my-app][WARNING] an info message from my-app $ cat application.log [2019-09-08 12:28:25,190][root][WARNING] this is an info message from the root logger [2019-09-08 12:28:25,190][my-app][WARNING] an info message from my-app

The output is repeated because we configured both, but that doesn’t mean they need to be. The formatting changed for the file-based logger, allowing a cleaner view in the console:

fromlogging.configimportdictConfigdictConfig({'version':1,'formatters':{'BASE_FORMAT':{'format':'[%(name)s][%(levelname)-6s]%(message)s',},'FILE_FORMAT':{'format':'[%(asctime)s] [%(name)s][%(levelname)-6s]%(message)s',},},'handlers':{'console':{'class':'logging.StreamHandler','level':'INFO','formatter':'BASE_FORMAT'},'file':{'class':'logging.FileHandler','level':'DEBUG','formatter':'FILE_FORMAT'}},'root':{'level':'INFO','handlers':['console','file']}})

Using dictConfig helps better visualize where things go and how they all tie together versus the more manual example earlier. For complicated setups where more than one logger is needed, the dictConfig way is better. Most of the web frameworks use the dictionary-based configuration exclusively.

Sometimes, the logging format is overlooked. It’s often seen as something cosmetic that provides visual appeal to a human reading the logs. While that is partly true, it is nice to have some square brackets to designate the logging level (for example, [CRITICAL]), but it can also be instrumental when other specifics of the environment, such as production, staging, or development, need separation. It might be immediately clear to a developer that the logs are from the development version, but it is extremely important to identify them if they are being forwarded around or collected in a central place. Dynamically applying this is done with environment variables and the use of logging.Filter in the dictConfig:

importosfromlogging.configimportdictConfigimportloggingclassEnvironFilter(logging.Filter):deffilter(self,record):record.app_environment=os.environ.get('APP_ENVIRON','DEVEL')returnTruedictConfig({'version':1,'filters':{'environ_filter':{'()':EnvironFilter}},'formatters':{'BASE_FORMAT':{'format':'[%(app_environment)s][%(name)s][%(levelname)-6s]%(message)s',}},'handlers':{'console':{'class':'logging.StreamHandler','level':'INFO','formatter':'BASE_FORMAT','filters':['environ_filter'],}},'root':{'level':'INFO','handlers':['console']}})

There is a lot going on in this example. It might be easy to miss a few things that got updated. First, a new class called EnvironFilter, which uses the logging.Filter as a base class, was added, and it defined a method called filter that accepts a record argument. This is how the base class wants this method to be defined. The record argument gets extended to include the APP_ENVIRON environment variable that defaults to DEVEL.

Then, in the dictConfig, a new key is added (filters) that names this filter the environ_filter, pointing to the EnvironFilter class. Finally, in the handlers key, we added the filters key that accepts a list, and in this case it will only have a single filter added: environ_filter.

The defining and naming of the filter feels cumbersome, but this is because our example is trivial. In more complex environments, it allows you to extend and configure without boilerplate filling the dictionary, making it easier to update or extend further.

A quick test in the command line indicates how the new filter shows the environment. In this example, a basic Pecan application is used:

$ pecan serve config.py Starting server in PID 25585 serving on 0.0.0.0:8080, view at http://127.0.0.1:8080 2019-08-12 07:57:28,157 [DEVEL][INFO ] [pecan.commands.serve] GET / 200

The default environment of DEVEL works, and changing it to production is one environment variable away:

$ APP_ENVIRON='PRODUCTION' pecan serve config.py Starting server in PID 2832 serving on 0.0.0.0:8080, view at http://127.0.0.1:8080 2019-08-12 08:15:46,552 [PRODUCTION][INFO ] [pecan.commands.serve] GET / 200

Common Patterns

The logging module offers a few good patterns that aren’t immediately obvious but are quite good to use as much as possible. One of these patterns is using the logging.exception helper. A common workflow looks like this:

try:returnexpensive_operation()exceptTypeErroraserror:logging.error("Running expensive_operation caused error:%s"%str(error))

This type of workflow is problematic on several fronts: it primarily eats the exception and just reports the string representation of it. If the exception isn’t obvious or if it happens in a location that is not immediately evident, then reporting TypeError is useless. When string replacement fails, you can get a ValueError, but if the code is obscuring the traceback, then the error doesn’t help:

[ERROR] Running expensive_operation caused an error:

TypeError: not all arguments converted during string formatting

Where did that happen? We know it happens when expensive_operation() is called, but where? In what function, class, or file? This type of logging is not only unhelpful, it is infuriating! The logging module can help us log the full exception traceback:

try:returnexpensive_operation()exceptTypeError:logging.exception("Running expensive_operation caused error")

The logging.exception helper will push the full traceback to the log output magically. The implementation doesn’t need to worry about capturing error as it was doing before, or even try to retrieve useful information from the exception. The logging module is taking care of everything.

Another useful pattern is to use the built-in capabilities of the logging module for string interpolation. Take this piece of code as an example:

>>>logging.error("An error was produced when calling: expensive_operation,with arguments:%s,%s"%(arguments))

The statement is requiring two string replacements, and it is assuming that arguments is going to have two items. If arguments fails to have two arguments, the above statement will break the production code. You never want to break production code because of logging. The module has a helper to catch this, report it as a problem, and allow the program to continue:

>>>logging.error("An error was produced when calling: expensive_operation,with arguments:%s,%s",arguments)

This is safe, and it is the recommended way to pass items to the statement.

The ELK Stack

Just like Linux, Apache, MySQL, and PHP were known as LAMP, you will often hear about the ELK stack: Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana. This stack allows you to extract information from logs, capture useful metadata, and send it to a document store (Elasticsearch) which then uses a powerful dashboard (Kibana) to display the information. Understanding each piece is crucial for an effective strategy when consuming logs. Each component of the stack is equally essential, and although you may find similar applications for each, this section concentrates on their actual roles in an example application.

Most production systems have been around for a while, and you will rarely get the chance to redo infrastructure from scratch. Even if you are lucky enough to get to design infrastructure from the ground up, it is possible to overlook the importance of log structure. A proper log structure is as important as capturing useful information, but when the structure is lacking, Logstash can help. When installing Nginx, the default logging output is similar to this:

192.168.111.1 - - [03/Aug/2019:07:28:41 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200 3700 "-" "Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Ubuntu; Linux x86_64; rv:68.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/68.0"

Some parts of the log statement are straightforward, such as the HTTP method (a GET) and the timestamp. If you can control the information, drop what is not meaningful, or include needed data, that is fine as long as you have a clear understanding of what all of these components are. The configuration for the HTTP server has these details in /etc/nginx/nginx.conf:

http {

log_format main '$remote_addr - $remote_user [$time_local] "$request" '

'$status $body_bytes_sent "$http_referer" '

'"$http_user_agent" "$http_x_forwarded_for"';

...

When you first look at the output, you might think that the dashes were for missing information, but this is not entirely correct. In the log output example, two dashes follow the IP; one is just cosmetic, and the second one is for missing information. The configuration tells us that a single dash follows the IP and then by $remote_user, which is useful when authentication is involved so that the authenticated user is captured. If this is an HTTP server that doesn’t have authentication enabled, the $remote_user can be dropped from the configuration (if you have access and permission to change the nginx.conf file), or it can be ignored with rules that extract the metadata from the logs. Let’s see in the next section how Logstash can help with its vast number of input plug-ins.

Tip

Elasticsearch, Logstash, and Kibana are usually not available in Linux distributions. Depending on the flavor of the distribution, the proper signing keys need to get imported, and the package manager needs to be configured to pull from the right repositories. Refer to the install sections on the official documentation. Make sure that the Filebeat package is also installed. This is a lightweight (yet powerful) utility for log forwarding. It will be used to send logs to Logstash later.

Logstash

The first step after deciding to go with the ELK stack is to hack some Logstash rules to extract information from a given source, filter it, and then ship it to a service (like Elasticsearch in this case). After Logstash gets installed, the path /etc/logstash/ becomes available with a useful conf.d directory where we can add multiple configurations for different services. Our use case is capturing Nginx information, filtering it, and then shipping it over to a local Elasticsearch service that should already be installed and running.

To consume logs, the filebeat utility needs to be installed. This is available from the same repositories that you enabled to install Elasticsearch, Kibana, and Logstash. Before configuring Logstash, we need to ensure that Filebeat is configured for the Nginx log files and the location of Logstash.

After installing Filebeat, add the log paths for Nginx and the default Logstash port for localhost (5044). The configuration in /etc/filebeat/filebeat.yml should have these lines defined (or uncommented):

filebeat.inputs:

- type: log

enabled: true

paths:

- /var/log/nginx/*.log

output.logstash:

hosts: ["localhost:5044"]

This allows Filebeat to look at every single path in /var/log/nginx/ and then forward it to the localhost instance of Logstash. If a separate log file for another Nginx application is required, it gets added here. Other defaults in the configuration file might be present, and those should be fine to leave as is. Now start the service:

$ systemctl start filebeat

Now create a new file in the Logstash configuration directory (in /etc/logstash/conf.d/), and name it nginx.conf. The first section that you should add handles the input:

input {

beats {

port => "5044"

}

}

The input section indicates that the source of the information will come from the Filebeat service using port 5044. Since all the file path configuration is done in the Filbeat configuration, not much else is necessary here.

Next, we need to extract the information and map it to keys (or fields). Some parsing rules need to be put in place to make sense of the unstructured data we are dealing with. For this type of parsing, use the grok plug-in; append the following configuration to the same file:

filter {

grok {

match => { "message" => "%{COMBINEDAPACHELOG}"}

}

}

The filter section now defines the usage of the grok plug-in that takes the incoming line and applies the powerful COMBINEDAPACHELOG, a collection of regular expressions that can accurately find and map all the components of the web server logs coming from Nginx.

Finally, the output section needs to set where the newly structured data should go:

output {

elasticsearch {

hosts => ["localhost:9200"]

}

}

This means that all structured data gets sent over to the local instance of Elasticsearch. As you can see, the configuration for Logstash (and the Filebeat service) was very minimal. There are several plug-ins and configuration options that can be added to further fine-tune the log collection and parsing. This batteries included approach is excellent for getting started without having to figure out extensions or plug-ins. If you are curious, browse through the Logstash source code and search for the grok-patterns file that contains COMBINEDAPACHELOG; the collection of regular expressions is quite the sight.

Elasticsearch and Kibana

After installing the elasticsearch package, there is little that you need to do to have a local setup running and ready to receive structured data from Logstash. Make sure the service is started and running without problems:

$ systemctl start elasticsearch

Similarly, install the kibana package and start the service up:

$ systemctl start kibana

Even though Kibana is a dashboard, and the ELK stack is not built with Python, these services are so well integrated that it demonstrates what great platform design and architecture truly are. After starting Kibana for the first time, while browsing through the log output it immediately starts looking for an instance of Elasticsearch running on the host. This is the default behavior of its own Elasticsearch plug-in with no extra configuration. The behavior is transparent, and the messaging tells you that is was able to initialize the plug-in and reach Elasticsearch:

{"type":"log","@timestamp":"2019-08-09T12:34:43Z",

"tags":["status","plugin:[email protected]","info"],"pid":7885,

"state":"yellow",

"message":"Status changed from uninitialized to yellow",

"prevState":"uninitialized","prevMsg":"uninitialized"}

{"type":"log","@timestamp":"2019-08-09T12:34:45Z",

"tags":["status","plugin:[email protected]","info"],"pid":7885,

"state":"green","message":"Status changed from yellow to green - Ready",

"prevState":"yellow","prevMsg":"Waiting for Elasticsearch"}

After changing the configuration to an incorrect port, the logs are very clear that the automatic behavior is not quite working:

{"type":"log","@timestamp":"2019-08-09T12:59:27Z",

"tags":["error","elasticsearch","data"],"pid":8022,

"message":"Request error, retrying

GET http://localhost:9199/_xpack => connect ECONNREFUSED 127.0.0.1:9199"}

{"type":"log","@timestamp":"2019-08-09T12:59:27Z",

"tags":["warning","elasticsearch","data"],"pid":8022,

"message":"Unable to revive connection: http://localhost:9199/"}

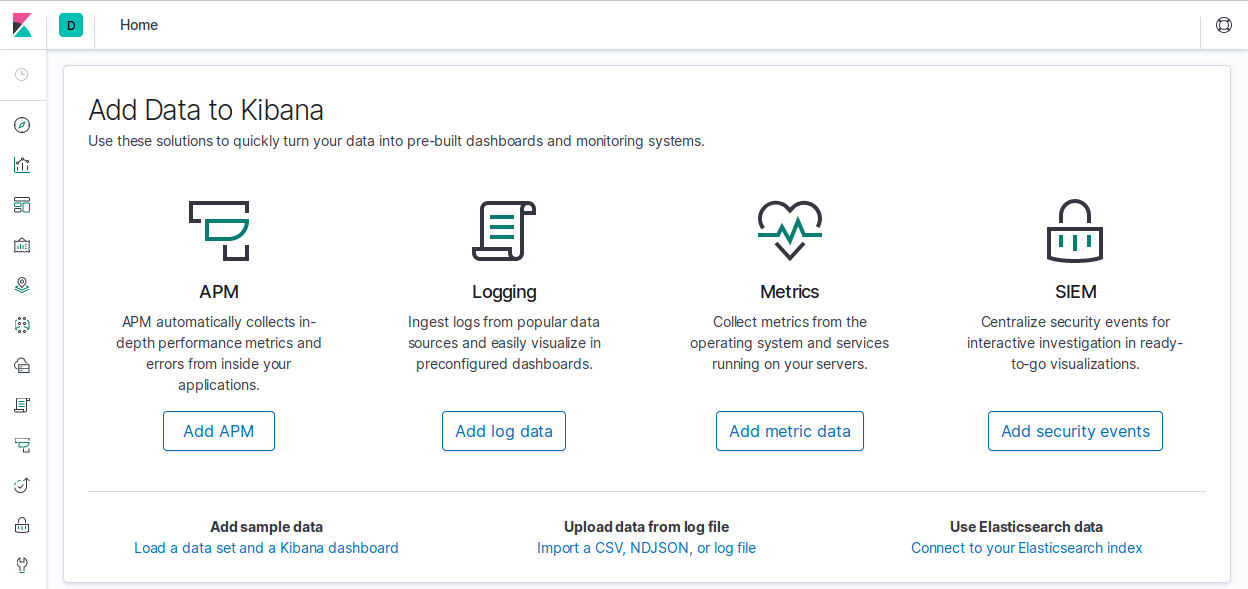

Once Kibana is up and running, along with Elasticsearch (on the correct port!), Filebeat, and Logstash, you will be greeted with a full-featured dashboard and plenty of options to get started, as in Figure 7-1.

Figure 7-1. Kibana’s landing dashboard page

Hit the local instance of Nginx to get some activity in the logs and start the data processing. For this example, the Apache Benchmarking Tool (ab) is used, but you can try it with your browser or directly with curl:

$ ab -c 8 -n 50 http://localhost/ This is ApacheBench, Version 2.3 <$Revision: 1430300 $> Copyright 1996 Adam Twiss, Zeus Technology Ltd, http://www.zeustech.net/ Licensed to The Apache Software Foundation, http://www.apache.org/ Benchmarking localhost (be patient).....done

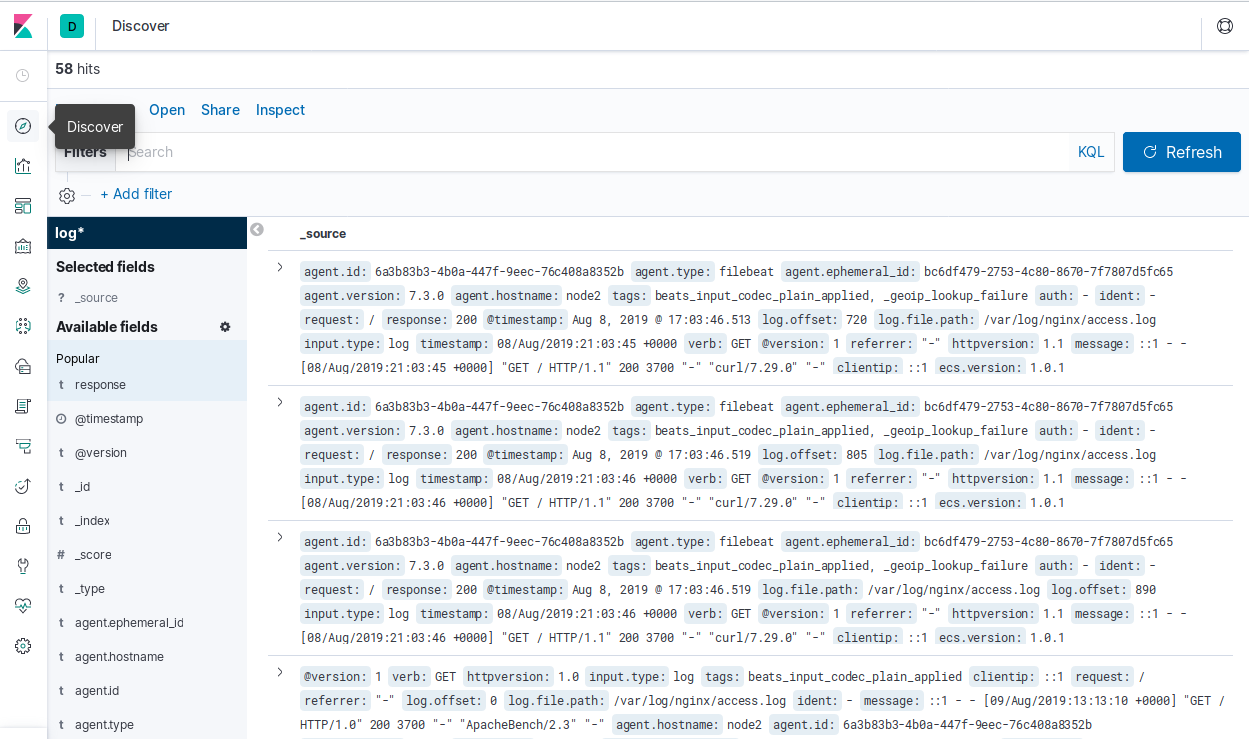

Without doing anything specific to configure Kibana further, open the default URL and port where it is running: http://localhost:5601. The default view offers lots of options to add. In the discover section, you will see all the structured information from the requests. This is an example JSON fragment that Logstash processed and is available in Kibana (which is sourcing the data from Elasticsearch):

..."input":{"type":"log"},"auth":"-","ident":"-","request":"/","response":"200","@timestamp":"2019-08-08T21:03:46.513Z","verb":"GET","@version":"1","referrer":""-"","httpversion":"1.1","message":"::1 - - [08/Aug/2019:21:03:45 +0000] "GET / HTTP/1.1" 200","clientip":"::1","geoip":{},"ecs":{"version":"1.0.1"},"host":{"os":{"codename":"Core","name":"CentOS Linux","version":"7 (Core)","platform":"centos","kernel":"3.10.0-957.1.3.el7.x86_64","family":"redhat"},"id":"0a75ccb95b4644df88f159c41fdc7cfa","hostname":"node2","name":"node2","architecture":"x86_64","containerized":false},"bytes":"3700"},"fields":{"@timestamp":["2019-08-08T21:03:46.513Z"]}...

Critical keys like verb, timestamp, request, and response have been parsed and captured by Logstash. There is lots of work to do with this initial setup to convert it into something more useful and practical. The captured metadata can help render traffic (including geolocation), and Kibana can even set threshold alerts for data, for when specific metrics go above or below a determined value.

In the dashboard, this structured data is available to be picked apart and used to create meaningful graphs and representations, as shown in Figure 7-2.

Figure 7-2. Structured data in Kibana

As we’ve seen, the ELK stack can get you started capturing and parsing through logs with minimal configuration and almost no effort. The examples are trivial, but should already demonstrate the immense capabilities of its components. More often than we would like to admit, we’ve been faced with infrastructure with a cron entry that is tailing logs and grepping for some pattern to send an email or submit an alert to Nagios. Using capable software components and understanding how much they can do for you, even in their simplest forms, is essential to better infrastructure, and in this case, better visibility of what that infrastructure is doing.

Exercises

-

What is fault tolerance and how can it help infrastructure systems?

-

What can be done for systems that produce huge amounts of logging?

-

Explain why UDP might be preferred when pushing metrics to other systems. Why would TCP be problematic?

-

Describe the differences between pull and push systems. When would one be better than the other?

-

Produce a naming convention for storing metrics that accommodates production environments, web and database servers, and different application names.

Case Study Question

-

Create a Flask application that fully implements logging at different levels (info, debug, warning, and error) and sends a metric (like a Counter) to a remote Graphite instance via a StatsD service when an exception is produced.