Eyes wide open: using trends, professional literature, and users to create a research canvas in libraries

Abstract:

This chapter explores the ways in which librarians and others might use the current literature and other professional resources to help define a research focus and better understand users. Trends in technology as possible areas for discovery are discussed.

Developing a “research agenda” is often an uphill battle for libraries. It can be a difficult task, especially if the agenda is completely unattached to documented user needs and service developments. A research agenda in and of itself is virtually useless—it is time-consuming, can yield a lot of data but very little information that is actually translated into meaningful improvements for users. In the best-case scenario, research can “collaboratively identify problems and opportunities, prototype and test solutions, and share findings through publications, presentations and professional interactions” (OCLC, 2010). In any library setting, deciding on a path of research often involves other entities and considerations. On the academic campus, it would be foolish to embark on a research agenda without first being very familiar with the campus’s research agenda, and without trying to create as much campus synchronicity as possible. In a public library setting, a library board or community board might be interested in certain topics, which should be considered as possible areas for further inquiry. In a research library, any research project should complement and support scholarly work currently going on in the major disciplines.

Ideally, library-related research should somehow be connected to user need. This may mean research that focuses on environmental and behavioral aspects of the user experience. In addition to being closely attuned to the changes being experienced by users both inside and outside of libraries, librarians and others who are interested in creating the best possible environments and services for users should also stay abreast of recent literature, reports, and research efforts by organizations that specialize in such. A few examples are the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR); the Coalition for Networked Information (CNI); the Online Computer Library Center (OCLC); the Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC); the Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL); the American Library Association (ALA); the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA); the American Library Association’s Library and Information Technology Association (LITA); the Research Information Network (RIN); Research Libraries UK (RLUK); the Society of College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL); the Centre for Information Behaviour and the Evaluation of Research (CIBER); “fact tanks” such as the Pew Research Center, and research organizations such as the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

Oftentimes, in library environments, the decision to conduct research is driven by crises, whether budgetary, staffing, or other. Research conducted in these conditions can often feel overwhelmingly critical, narrowly focused, rushed, and reactionary. It is rare to find day-to-day decisions driven by empirical research. Moreover, it is rare to find library environments where research is the norm. And rightfully so—libraries of all types are traditionally known as service environments, spaces where access to subject expertise and collections are made available to users. They are not necessarily known as places where decisions are based on research data, as is the case with profit-driven organizations.

This has been the case historically. The modern-day reality is a little different. Libraries the world over are facing the challenge of implementing drastic changes or running the risk of becoming less useful to a community of users who have unprecedented access to resources and information. There is a sense of competition, and many libraries in the West have begun to define themselves not in relation simply to their print collections, but with regard to the expertise of librarians, special collections, archives, and community programming. The Queensborough Public Library in Queens, New York, is probably best known not for its vast collection of print materials, but for the development of its “New Americans” program, which featured aggressive outreach efforts, diverse programming, and multilanguage print materials for new Americans across the borough of Queens. This program became a model for other public library systems in the United States seeking to provide more inclusive programming for an increasingly multiethnic user body. The decision to develop this type of program at the Queensborough Public Library was driven by demographic data, which suggested new Americans were increasingly moving into the borough, and were in need of a wide variety of educational and employment services (Pyati, 2003). Research into these environmental changes guided the subsequent development of the program.

Getting started is the hardest part, and in addition to being familiar with what is being talked about within the profession, and by users, a thorough literature review on the topic of interest, or on methods for investigating certain topics can also be enlightening. It is likely that someone somewhere has already investigated and written about at least some elements of any particular research topic, so a literature review can help librarians and researchers decide what not to research. Radford and Snelson (2009) define five current trends for library research: reference services, information literacy, collection management, knowledge organization, and leadership. Information seeking is another area that researchers continue to examine (Nicholas et al., 2009; Timmers and Glas, 2010; Jamali and Nicholas, 2010; Prendiville et al., 2009). Wildemuth (2002) provides an overview of methods to investigate information-seeking behavior, including the use of diaries, card sorts, structured observation, and ethnographies. All of these topics are relatively traditional and predictable areas for library research, but certainly still relevant. However, it is not impossible to imagine that, in the future, these areas will become less relevant, and other research areas more so, simply because of the ever-changing nature of the user and the world around us.

The trick to discovering the areas that might benefit from further exploration within any library is to find the intersection of current trends, future trends, new technologies, and the libraries’ strategic plan, user need, and future goals. It will not always be the case that areas overlap, but there may be some commonalities that draw your attention. Using ideas generated by researching the literature, paying attention to what is happening in the surrounding world, educational trends, technology, and consumer practices, can all inform research practices. It is important that librarians be able to see the potential for these overlapping spaces in relation to what they do.

Although not all of the research material generated by research or scholarly organizations will be relevant for all libraries, there is often quite a bit of useful information that can inform research practices at the local level. The next section of this chapter will present examples of trends, changes, and developments in the library world, drawn from the literature, with a specific focus on academic and research libraries. No one type of research approach is suggested here, as you will see; these research questions may be investigated with either qualitative or quantitative methods, or both.

Generational differences and the digital landscape

There is quite a bit of literature that addresses the technological habits and behaviors of the population of people born between roughly 1980 and 1994 (Long, 2005; Oblinger, 2003; Oblinger and Oblinger, 2005; Prensky, 2001, 2005; Tapscott, 1998, 2008; Frand, 2000; Bennett et al., 2008; Jukes et al., 2010; Rosen, 2010). Prensky (2001) described this group as digital natives, Tapscott (1998) and Carlson (2005) referred to them as the “Net generation,” and Howe and Strauss (2003) called them “millennials.” The “Nintendo Generation” was coined by Green et al. (2003); “Cyberkids” by Facer and Furlong (2001); and “Screenagers” by Rushkoff (1996). Obviously, young people born between 1980 and 1994 are an incredibly diverse and heterogeneous group, and the global use of the terms above without differentiation has been criticized by a number of scholars (Bennett et al., 2008; Helsper, 2008). Regardless, an entirely new area of research was created around the excitement spurned by this intriguing new generation.

Juxtaposed against this new population, everyone else is digital immigrants (Prensky, 2001). Born before 1980, the group of digital immigrants “includes most teachers,” who “lack the technological fluency of the digital natives and find the skills possessed by them almost completely foreign” (Bennett et al., 2008, p. 777). Digital immigrants were not born into the digital era that we find ourselves in now; they are transplants from an earlier time not defined by technology. This gap presents certain challenges, especially when it comes to teaching and education (Rosen, 2010; Jukes et al., 2010; Brown, 2002; Levin and Arafeh, 2002; Levin et al., 2002; Prensky, 2005).

According to Palfrey and Gasser (2008) “digital natives live much of their lives online, without distinguishing between the online and the offline” (p. 4). Their identities, the authors suggest, are not split into separate real and virtual identities; rather, they just have one that is a mixture of both online and offline representations (p. 4). Palfrey and Gasser (2008) present a mixture of anecdotal and demographic data to support their idea of what it means to be born digital. One of the more critical observations in terms of libraries and other information spaces is how digital natives relate to information, which is drastically different from the way their parents relate to information. “Digital natives are coming to rely upon this connected space for virtually all of the information they need to live their lives” (p. 6). “They have little use for those big maps you have to fold on the creases, or for TV listings, travel guides, or pamphlets of any sort; the print versions are not obsolete, but they do strike digital natives as rather quaint” (Palfrey and Gasser, 2008, p. 6). Although the Palfrey and Gasser book was only written in 2008, much of what the authors present is old news by now. Yet, there are a number of take-away lessons about generational differences that might inform library research in certain settings.

Silipigni Connaway (2008) discusses some of the habits and main information service preferences of “millennials,” which are relevant for library settings:

![]() Immediacy. Millennials tend to be impatient, pay less attention to spelling and grammar and have a low tolerance for complex searching. Convenience is key.

Immediacy. Millennials tend to be impatient, pay less attention to spelling and grammar and have a low tolerance for complex searching. Convenience is key.

![]() More choices and selectivity. Millennials prefer multiple formats and media.

More choices and selectivity. Millennials prefer multiple formats and media.

![]() Collaboration and teamwork. Millennials prefer to collaborate virtually and in person as is demonstrated in their participation in social networking sites.

Collaboration and teamwork. Millennials prefer to collaborate virtually and in person as is demonstrated in their participation in social networking sites.

![]() Experiential learning. Millennials tend to be nonlinear thinkers, which may be attributed to surfing the web.

Experiential learning. Millennials tend to be nonlinear thinkers, which may be attributed to surfing the web.

Accordingly, Silipigni Connaway (2008) suggests several ways in which libraries can become more meaningful to this group of users, by:

![]() delivering resources efficiently and quickly at the point of need at the network level;

delivering resources efficiently and quickly at the point of need at the network level;

![]() making library catalogs easier to use;

making library catalogs easier to use;

![]() accommodating different discovery and access preferences;

accommodating different discovery and access preferences;

![]() allowing users to personalize the interface;

allowing users to personalize the interface;

![]() offering multiple modes of service—virtual, face-to-face and telephone;

offering multiple modes of service—virtual, face-to-face and telephone;

![]() providing opportunities for collaboration online and in physical library spaces.

providing opportunities for collaboration online and in physical library spaces.

Palfrey and Gasser (2008) suggest that accuracy is another area that all users, including millennials, should pay attention to, but do not always. The importance of accuracy is growing at a very fast pace, as a direct result of so much information being available. At the same time, accuracy and quality can be easily overlooked. These are complex, often obscure concepts that can mean different things to different people. Accuracy of information on the Internet, Palfrey and Gasser (2008) point out, has a very different meaning for a surgeon who is researching the latest surgical techniques than it does for a ninth-grader writing a research paper. Markets, social norms, computer code, and even law and regulations, can have an impact on accuracy and quality (Palfrey and Gasser, 2008); however, the authors assert that “education is the best way to help digital natives manage the information-quality problem. Digital literacy is increasingly a critical skill for digital natives to learn” (2008, p. 180).

Information literacy has been, and continues to be, an area that librarians are familiar with. More recently, some librarians and educators have started to focus on “transliteracy,” which incorporates new and emerging technologies and skills—“Transliteracy is the ability to read, write, and interact across a range of platforms, tools, and media from signing and orality through handwriting, print, TV, radio and film, to digital social networks” (Transliteracy Interest Group of the LITA, 2010). However, this new landscape and skill set is defined; the role of digital literacy educator is one that is familiar to many librarians. We also know that information and digital literacy teaching practices continue to face challenges about efficacy, impact, and pedagogical soundness (Tyner, 1998; Bowden and DiBenedetto, 2001; Portmann and Roush, 2004; Sanborn, 2005). Digital literacy is not just an issue for students. A recent survey by the Federal Communications Commission, Broadband Adoption and Use in America, found that 22 percent of respondents did not have Internet access at home because of poor digital literacy skills (Horrigan, 2010).

Given the above, what research questions might be relevant for librarians, based on what we know so far about the impact of technology on learning, writing, and critical thinking skills? And, how best to investigate these phenomena? Investigating user research behavior, especially in settings where the users are students, may be part of a larger research agenda that includes an informed approach to information and digital literacy. Qualitative approaches may include research diaries, contextual analysis of pre- and post-instruction term papers, and even analyses of librarians’ teaching approaches and pedagogical application. The ramifications of understanding digital competencies go far beyond the ability to craft a sound research paper. Librarians and other educators play an important role in helping to prepare students and other learners for participation in a democratic society (Kranich, 2001). The Knight Commission’s Report on the Information Needs of Communities in a Democracy (2009) presents 15 recommendations for meeting community information needs in a digital age, including “integrate digital and media literacy as critical elements for education at all levels through collaboration among federal, state, and local education officials”; “fund and support public libraries and other community institutions as centers of digital and media training, especially for adults”; and “engage young people in developing the digital information and communication capacities of local communities” (Knight Commission, 2009). Libraries can therefore set exploratory research agendas to be inclusive of these ideas, with an eye towards integrating best instructional and outreach practices into daily activities.

Privacy and copyright issues are not new or relevant solely to the digital era, but they are enjoying more of the spotlight in this new environment. Palfrey and Gasser (2008) make an interesting observation about digital natives and their attitudes towards privacy. “Most young people are extremely likely to leave something behind in cyberspace that will become a lot like a tattoo—something connected to them that they cannot get rid of later in life, even if they want to, without a great deal of difficulty” (p. 53). Palfrey and Gasser (2008) suggest that, astonishingly, by the time a digital native enters the workforce, there may be hundreds or thousands of digital files on the Internet about them, over which they have no control and most likely are not even aware of.

Many libraries, especially academic libraries, have programs and literature to educate users about privacy and copyright matters. Many librarians will also tell you that much of the literature and programming around these issues are ignored, until someone lands in trouble. Privacy and copyright are obviously two different concerns, and libraries tend to be more focused on the latter of the two. One sobering point made by Palfrey and Gasser (2008, p. 73) has to do with the blind trust that society seems to have when operating in the online environment. “We as societies are relying heavily, even more than we realize, on trust—of third parties we don’t know well at all” to store and guard personal information that we share online. Once again, education seems to be the way forward in terms of modeling best practices for digital natives. Parents, teachers, and technology companies (Palfrey and Gasser, 2008) all have a role to play. Librarians also fit into this matrix, since both physical and virtual library spaces may be where students first encounter serious challenges, especially with regard to copyright.

In addition, academia provides a familiar backdrop from which to study the intersection of research habits and privacy. Silipigni Connaway (2008) noted an interesting concern of a graduate student with regard to virtual reference services: “I always worry that [chat sessions] are being saved … if the department would get a report about what questions [I asked].” A recent PEW Internet & American Life Project survey (2010a) suggests that privacy concerns are manifest differently by the youngest of today’s technology users, the group of young adults that are now and will become the heaviest of information users. “New social norms that reward disclosure are already in place among the young. The experts also expressed hope that society will be more forgiving of those whose youthful mistakes are on display in social media such as Facebook picture albums or YouTube videos” (PEW Internet & American Life Project, 2010a). These same experts also suggest that “new definitions of ‘private’ and ‘public’ information are taking shape in networked society” and that, although “millennials might change the kinds of personal information they share as they age, but the aging process will not fundamentally change the incentives to share” (PEW Internet & American Life Project, 2010a).

The state of the research and academic library

The question that is still being asked by many librarians and others is: What is the future of the library? Without a crystal ball, we just do not have the answer to that yet, and, since the question is rhetorical in nature, the answer will continue to elude us. That particular question has been asked in a number of different ways, for a very, very long time now, although we tend to think of it as strictly being tied to the recent digital changes in the environment. As far back as 1949, Coney et al. (1949) discussed the future of the academic library. Researchers have also talked about methods to gather data to address this question—for example, Wennerberg (1972) and Saunders (2009) discuss using the Delphi technique to plan the future of libraries. There are bibliographies on the subject (Sapp, 2002), and far too many articles to count (Crawford and Gorman, 1995; Wainright, 1996; Harvey, 2009; Osif, 2008; Ross and Sennyey, 2008; Shuman, 1989, 1997). Given this, does it make sense to take this on as part of a research agenda within any given library? That all depends. Certainly, the future of libraries of all types is still of great concern; hence the continued efforts by researchers to publish on the topic. Familiarity with the literature can provide a framework for identifying very specific library research that can benefit users. The research library in particular has been the topic of much speculation about its future.

In the report No Brief Candle: Reconceiving Research Libraries for the 21st Century, the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) (2008) outlines several areas for research libraries to consider moving forward. The report, which by now is somewhat dated, represents a broader contextual landscape for academic and research libraries, wherein identity, purpose, and future utility are greatly debated and discussed. The report does touch on a number of areas that remain highly relevant for libraries and constitute some interesting areas for further exploration. Aspects related to preservation, scholarly communications, teaching, collaboration, scholarly publishing, relationships with faculty, librarian identity, and and digital technologies are considered. Internationally, organizations such as the Joint Information Systems Committee, the Research Information Network (RIN), the Research Libraries UK (RLUK), the Research Libraries Network (RLN), and the Society of College, National and University Libraries (SCONUL) are collaborating to provide consultation and leadership for academic and research libraries in order to form a “fresh focus and formulate strategies to ensure the sector continues to be a leading global force” (RIN, 2010).

ACRL (2010, p. 286) lists the top ten trends impacting the academic library as follows:

![]() Academic library collection growth is driven by patron demand and will include new resource types.

Academic library collection growth is driven by patron demand and will include new resource types.

![]() Budget challenges will continue and libraries will evolve as a result.

Budget challenges will continue and libraries will evolve as a result.

![]() Changes in higher education will require that librarians possess diverse skill sets.

Changes in higher education will require that librarians possess diverse skill sets.

![]() Demands for accountability and assessment will increase.

Demands for accountability and assessment will increase.

![]() Digitization of unique library collections will increase and require a larger share of resources.

Digitization of unique library collections will increase and require a larger share of resources.

![]() Explosive growth of mobile devices and applications will drive new services.

Explosive growth of mobile devices and applications will drive new services.

![]() Increased collaboration will expand the role of the library within the institution and beyond.

Increased collaboration will expand the role of the library within the institution and beyond.

![]() Libraries will continue to lead efforts to develop scholarly communication and intellectual property services.

Libraries will continue to lead efforts to develop scholarly communication and intellectual property services.

![]() Technology will continue to change services and required skills.

Technology will continue to change services and required skills.

![]() The definition of the library will change as physical space is repurposed and virtual space expands.

The definition of the library will change as physical space is repurposed and virtual space expands.

In 2007, ACRL published the top ten assumptions about the future of academic libraries and librarians:

![]() There will be an increased emphasis on digitizing collections, preserving digital archives, and improving methods of data storage and retrieval.

There will be an increased emphasis on digitizing collections, preserving digital archives, and improving methods of data storage and retrieval.

![]() The skill set for librarians will continue to evolve in response to the needs and expectations of the changing populations (students and faculty) that they serve.

The skill set for librarians will continue to evolve in response to the needs and expectations of the changing populations (students and faculty) that they serve.

![]() Students and faculty will increasingly demand faster and greater access to services.

Students and faculty will increasingly demand faster and greater access to services.

![]() Debates about intellectual property will become increasingly common in higher education.

Debates about intellectual property will become increasingly common in higher education.

![]() The demand for technology-related services will grow and require additional funding.

The demand for technology-related services will grow and require additional funding.

![]() Higher education will increasingly view the institution as a business.

Higher education will increasingly view the institution as a business.

![]() Students will increasingly view themselves as customers and consumers, expecting high-quality facilities and services.

Students will increasingly view themselves as customers and consumers, expecting high-quality facilities and services.

![]() Distance learning will be an increasingly more common option in higher education, and will coexist but not threaten the traditional bricks-and-mortar model.

Distance learning will be an increasingly more common option in higher education, and will coexist but not threaten the traditional bricks-and-mortar model.

![]() Free public access to information stemming from publicly funded research will continue to grow.

Free public access to information stemming from publicly funded research will continue to grow.

![]() Privacy will continue to be an important issue in librarianship. (Allen, Mullins and Hufford, 2007)

Privacy will continue to be an important issue in librarianship. (Allen, Mullins and Hufford, 2007)

Each of these topics represents areas that can be explored further in a variety of ways, at the same time, each of these topics has been covered at great length in the literature already. Librarians might use information on trends and recent developments within the research library setting to make connections to observations and data they already have about their users. A good example of this is mobile technology. There is no longer any question about users’ preference for ways to access information efficiently from wherever they are, and, in many cases, this access involves a mobile device. Some libraries have begun to experiment with mobile-enabled library websites; others still wonder if it is really necessary to meet user need in this way.

One interesting development in terms of exploring the future of the research library is the use of scenarios—a decidedly qualitative way to collect and analyze data. Scenarios are more commonly found within usabilty and interface evaluation settings (Isaac et al., 2008), but in this case the use of scenarios is a little different. Scenarios in this sense are mostly used within business settings to help employees brainstorm, but they can be used by any organization. A scenario is essentially a story “about how the future might unfold for our organizations, our communities and our world. Scenarios are not predictions. Rather, they are provocative and plausible accounts of how relevant external forces—such as the future political environment, scientific and technological developments, social dynamics, and economic conditions— might interact and evolve, providing our organizations with different challenges and opportunities” (Global Business Network, 2010). Library scenarios are not new—Giesecke (1998) edited a volume titled Scenario Planning for Libraries, and Dugan and Hernon (2002) used scenarios to highlight the importance of library policy. Authors have also written about scenarios that detail the death of the library (Putnam et al., 2004). The Association of Research Libraries (ARL, 2010) recently embarked on a project to help research library administrators set their libraries up for maximum success, using this technique:

These scenarios will capture broad environmental drivers affecting research libraries. Each scenario will tell a different plausible story that starts at the current state and takes the reader out into highly divergent future situations of research libraries, rather than detailing what research libraries might look like organizationally. Future scenarios will highlight and deepen understanding of the social, technological, economic, political/regulatory, and environmental driving forces impacting research libraries in the future. (ARL, 2010)

The public library system of New South Wales also used scenarios as a collective, experiential, and holistic approach to developing strategy, by way of “imagination and analysis” (Library Council of New South Wales, 2010, p. 6).

Although hardly a trend, the turn away from the traditional methods for exploring future direction and strategy—by committee, collection of data from canned, commercial surveys, SWOT analysis, “environmental scanning, extrapolations of past trends, or individual forecasting” (ARL, 2010)—towards a more organic and qualitative method is intriguing at best. Librarians can certainly keep tabs on the progress of these two projects and others as they emerge, to determine whether such an approach might be useful.

Understanding the role of technology through research

Curious about the cloud

Cloud computing represents an approach to data access and storage that came into the spotlight starting in the 1980s. There are many definitions out there, but for the most part cloud computing designates the ability of the user to store, access, and manipulate data regardless of the device they are using, or where they are, by way of the Internet. Knorr and Gruman (2008) suggest that cloud computing is just “virtual servers available over the Internet.” Chudnov (2010) reminds us that cloud computing is hardly new; it is, however, much more trendy right now: “It’s strange to watch something you’ve taken for granted for years suddenly become ‘a thing.’ Cloud computing is definitely a thing now, but it’s not new and it’s not even novel” (p. 33). NIST (National Institutes of Standards and Technology) defines cloud computing as “a model for enabling convenient, on-demand network access to a shared pool of configurable computing resources (e.g., networks, servers, storage, applications, and services) that can be rapidly provisioned and released with minimal management effort or service provider interaction. This cloud model promotes availability and is composed of five essential characteristics, three service models, and four deployment models” (Mell and Grance, 2009).

The PEW Internet & American Life Project (2010b, p. 2) suggests that “among the most popular cloud services now are social networking sites (the 500 million people using Facebook are being social in the cloud), webmail services like Hotmail and Yahoo mail, microblogging and blogging services such as Twitter and WordPress, video-sharing sites like YouTube, picture-sharing sites such as Flickr, document and applications sites like Google Docs, social-bookmarking sites like Delicious, business sites like eBay, and ranking, rating, and commenting sites such as Yelp and TripAdvisor”. In a survey, the PEW Internet & American Life Project (2010b) found that 56 percent of Internet users use webmail; 34 percent store photos online; and 29 percent use online applications such as GoogleDocs.

There are different cloud computing service models. Software (SaaS), Platform (PaaS) and Infrastructure (IaaS) can all be delivered as services via the cloud, whereas previously these elements were physically bound to the desktop or server. The choices for service providers are also increasing, with some of the better-known applications being household names. Amazon’s S3 service allows for data storage, and EC2 allows developers to run computing resources on Amazon’s platform (Amazon, 2010). Zoho (2010) is an online suite of cloud “productivity and collaboration apps.” Google provides a suite of applications that operate in the cloud, including Gmail, Google Docs, Google Wave, Google Calendar, Google Groups, Google Sites, and Google Video (Google, 2010), as well as a developers’ application called Google App Engine.

Librarians have also started to ask how cloud computing can benefit their institutions and their users (Chudnov, 2010; Hastings, 2009; Buck, 2009; Breeding, 2009). Breeding (2009) states “cloud computing offers for libraries many interesting possibilities that may help reduce technology costs and increase capacity, reliability, and performance for some types of automation activities. Cloud computing has made strong inroads into other commercial sectors and is now beginning to find more traction in the library technology sector” (p. 22).

Repositories, storage, collaborative research and publishing, collaborative teaching, catalogs, and metadata are all elements of library services which represent ways in which libraries can take advantage of cloud computing. “OCLC probably ranks as the most prominent example of cloud computing in the library arena. The WorldCat platform involves a globally distributed infrastructure that involves the largest scale library-specific implementation” (Breeding, 2009, p. 26). User-generated content such as that found on Facebook, online photo applications, Twitter, blogs, wikis, and YouTube is indicative of a trend that indicates a certain level of comfort with relinquishing some degree of control over content. In many cases, cloud computing represents a scalable and less expensive way to provide a host of services.

For many libraries, however, it can seem like a leap of faith. Complicating the use of cloud computing are issues related to data security, privacy, bandwidth, compatibility, and quality of service (Anderson and Rainie, 2010). If a user’s data is not on their desktop, it is someplace else, and someone has to be responsible for its integrity and security. For these reasons, this particular topic is an excellent area for further exploration for librarians who are curious. Qualitative and quantitative data would be helpful. Qualitative data could include feedback from users about how they feel about storing their information and data in the cloud; quantitative data might include data about which devices users typically use to access their information on the go. Cloud computing application within libraries also has financial, infrastructure, and staffing considerations, so it stands to reason that the more that librarians can learn about the challenges and benefits associated with its use, the better. As Breeding suggests,

The days of each library operating its own local servers have largely passed. This approach rarely represents the best use of library space and personnel. As libraries develop the next phase of their technology strategies, it’s important to think beyond the locally maintained computer infrastructure that increasingly represents an outdated and inefficient model. Colocation, remote hosting, virtualization, SaaS, and cloud computing each offers opportunities for libraries to expend fewer resources on maintaining infrastructure and to focus more on activities with direct benefit on library services. (2009, p. 26)

Going mobile

Mobile technology is another area that consistently creates a sense of possibility in terms of supporting the user experience. Some libraries have found a way to integrate mobile technology into their landscape, not as an afterthought, but as a priority. Users who access information by way of cell phone/PDA represent a quickly growing segment of the population, and they are library users as well. Wireless devices are also growing in number and type—smartphones, Droids, the iTouch, iPad, and iPhone, Kindle, Sony eReader, and so on—are all wireless devices that are popular. Interactions with these devices can be textual, visual, or auditory in nature, and users may be involved in different types of interactions at any one time.

According to the PEW Internet & American Life Project (2010c), 59% of all Americans now go online wirelessly, using a laptop, cellphone or PDA. There has been a noticeable increase in the types of activities wireless users engage in:

![]() 54% have used their mobile device to send someone a photo or video

54% have used their mobile device to send someone a photo or video

![]() 23% have accessed a social networking site using their phone

23% have accessed a social networking site using their phone

![]() 20% have used their phone to watch a video

20% have used their phone to watch a video

![]() 15% have posted a photo or video online

15% have posted a photo or video online

![]() 11% have purchased a product using their phone

11% have purchased a product using their phone

![]() 11% have made a charitable donation by text message

11% have made a charitable donation by text message

![]() 10% have used their mobile phone to access a status update service such as Twitter

10% have used their mobile phone to access a status update service such as Twitter

Another interesting finding from the PEW report has to do with the demographics related to wireless and particularly cell phone/PDA use. African-Americans and Latinos are wireless users in large numbers (64 percent and 63 percent respectively), and 87 percent of African-Americans and Latinos own a cellphone (PEW Internet & American Life Project, 2010c). What are users doing in mobile environments? They are searching for content, locations, multimedia, using applications such as Google Mobile. They are managing their mobile content using services like Zinadoo and Mobifeeds, and transcoding data using sites like Skweezer. They are looking for content using spoken search (Voicebox); personalizing searches using services like Stumbleupon; and using SMS-Web texting services like Google SMS and Joopz.

For the average library, going mobile requires technological expertise, human resources, and financial commitment. It can be unclear if the benefits to users are worth the effort. Exploring the possible ways to integrate mobile technology is certainly a research area that is highly relevant today. Librarians and others have been dabbling in this area for a long time now, trying to figure out what going mobile might mean for libraries (Fox, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005). A random virtual visit to a cross-section of library websites via your mobile device will produce information that is often unreadable, unloadable, and unusable. It is not just libraries that do not provide mobile-enabled access—many sites on the web just are not there yet. In a recent survey of 111 Association of Research Libraries (ARL) members’ university websites, 39 were mobile-enabled, and out of those 39, 14 libraries had mobile-enabled presentation for some segments of their websites (Aldrich, 2010). Despite the fact that most libraries do not have web-enabled content, libraries of all types are adding mobile-enabled websites to their information landscape, including American University, Harvard University, Regina Public Library, and New York Public Library.

The matrix: a tool for the beginning

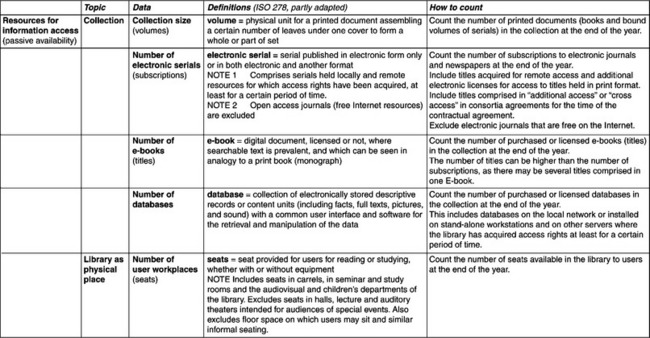

There are many different paths that lead to discovery, and library research is no different. How can librarians and others combine strategic plans, research agendas, current developments, and user need to come up with research questions that are relevant to their jobs, and executable in terms of methodology? It is not an easy task, especially if librarians are interested in a more qualitative approach. There are a few guidelines for collecting quantitative data and their evaluation. For instance, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) produced a matrix which lists the research topic, types of data to collect, definitions, and how to count the data (IFLA, 2007; see Figure 4.1).

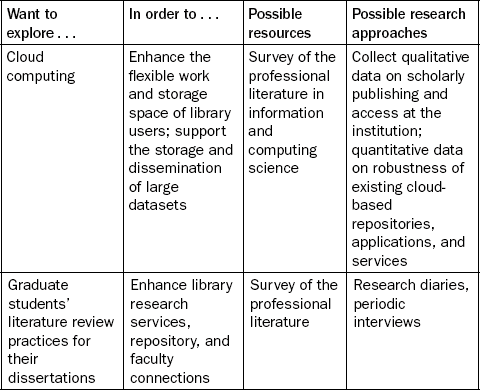

Librarians can create their own matrix to help stimulate discussion during the brainstorming phase. Table 4.1 provides an example of one way to begin visualizing all the many questions and elements that can help to build a research framework, regardless of the approach. This matrix can be reorganized and filled in any order—the point is to get librarians and researchers in any given setting talking about the things that are important to users, the connection to library goals, and the ways in which research can identify challenges, problems, and, most importantly, opportunities. It is not meant to be a formal exercise—informal discussions with notes on newsprint or a blackboard will do just fine.

As is the case with exploring any new technology or new service, it is important for researchers to get out and experience how other libraries and information spaces have interpreted and met user need by way of research practices. Research can tell us a lot about certain aspects, but it cannot tell us everything.

References

Aldrich, A., Universities and libraries move to the mobile web. EDUCAUSE Quarterly. 2010;33(2) Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/EDUCAUSE+Quarterly/EDUCAUSEQuarterlyMagazineVolum/UniversitiesandLibrariesMoveto/206531

Allen, F.R., Mullins, J.L., Hufford, J.R. Top ten assumptions for the future of academic libraries and librarians: A report from the ACRL research committee. Retrieved from https://wendolene.tosm.ttu.edu/handle/2346/493, 2007.

Amazon. Retrieved from http://aws.amazon.com/ec2/, 2010.

Anderson, J., Rainie, L., Pew Internet & American Life Project Report: The future of the internet, social networking, communities: The future of social relations, 2010. Retrieved from http://pewinternet.org/~/media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Future_ofJntemet_%202010_social_relations.pdf

Association of College & Research Libraries (ACRL). 2010 top ten trends in academic libraries: A review of the current literature. College & Research Libraries News. 2010; 71(6):286–292.

Association of Research Libraries. Retrieved from http://www.arl.org/rtl/plan/scenarios/index.shtml, 2010.

Bennett, S., Maton, K., Kervin, L. The “digital natives” debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology. 2008; 39(5):775–786.

Bowden, T.S., DiBenedetto, A. Information literacy in a biology laboratory session: An example of librarian-faculty collaboration. Research Strategies. 2001; 18(2):143–149.

Breeding, M., The advance of computing from the ground to the cloud. Computers in Libraries. 2009 November/ December. Retrieved from http://www.librarytechnology.org/ltg-displaytext.pl?RC=14384

Brown, J.S., Growing up digital: How the web changes work, education, and the ways people learn. Education at a Distance USDLA Journal 2002; Retrieved from http://www.usdla.org/html/journal/FEB02_Issue/article01.html

Buck, S. Libraries in the cloud: Making a case for Google and Amazon. Computers in Libraries. 2009; 29(8):6–10.

Carlson, S., The net generation goes to college. Chronicle of Higher Education 2005; October 7. Retrieved from http://chronicle.com/free/v52/i07/07a03401.htm

Chudnov, D. A view from the clouds. Computers in Libraries. 2010; 30(3):33–35.

Coney, D., McKeon, N.F., Branscomb, B.H. The future of libraries in academic institutions. Harvard Library Bulletin; 1949.

Connaway, L.S., Make room for the Millennials. NextSpace 2008; 10:18–19 Retrieved from http://www.oclc.org/nextspace/010/research.htm

Council on Library, Information Resources (CLIR), No brief candle: Reconceiving research libraries for the 21st century, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.clir.org/pubs/reports/pub142/pub142.pdf

Crawford, W., Gorman, M. Future Libraries: Dreams, Madness & Reality. Chicago, IL: American Library Association; 1995.

Dugan, R.E., Hernon, P. Outcomes assessment: not synonymous with inputs and outputs. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2002; 28(6):376–380.

Facer, K., Furlong, R. Beyond the myth of the “Cyberkid”: Young people at the margins of the information revolution. Journal of Youth Studies. 2001; 4(4):451–469.

Fox, M., PDAs and handhelds in libraries. Presentation given at ACRL/NEC Conference, January 15, 2002, 2002 Retrieved from http://web.simmons.edu/~fox/pda/

Fox, M., PDAs in academic libraries: We’ve got the whole world in our palms. Presentation given at State University of New York Librarians Association (SUNYLA) 35th Annual Conference. June 4, 2003. Stony Brook, NY, 2003. Retrieved from http://web.simmons.edu/~fox/pda/

Fox, M. (2004) PDAs in libraries. Presentation given at Computer in Libraries, Washington, DC, March 12, 2004. Retrieved from http://web.simmons.edu/fox/pda/.

Fox, M., Building communities in the “palm” of your hand. Presentation given at Computer in Libraries. 2005 Washington, DC, March 17, 2005. Retrieved from http://web.simmons.edu/~fox/pda/

Frand, J. The information-age mindset: changes in students and implications for higher education. EDUCAUSE Review. 2000; 35:14–24.

Giesecke, J. Scenario Planning for Libraries. Chicago, IL: American Library Association; 1998.

Global Business Network (GBN). Retrieved from http://www.gbn.com/about/scenario_planning.php, 2010.

Google. Retrieved from http://www.google.com/apps, 2010.

Green, B., Reid, J., Bigum, C. Teaching the Nintendo generation: Children, computer culture and popular technologies. In: Howard S., ed. Wired-up: Young people and the electronic media. London: Routledge; 2003:19–42.

Harvey, S. The Future of Libraries Without Walls. London: Facet Publishing; 2009.

Hastings, R. Cloud computing. Library Technology Reports. 45(4), 2009.

Helsper, E.J., Digital inclusion: An analysis of social disadvantage and the information society. Department of Communities and Local Government, London, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/communities/pdf/digitalinclusionsummary

Horrigan, J.B., Broadband adoption and use in America. Federal Communications Commission, 2010. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/public/resources/documents/FCCSurvey.pdf

Howe, N., Strauss, W. Millennials go to College. Washington, DC: American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers; 2003.

International Federation of Library Associations Institutions (IFLA), Global statistics for the 21st century, 2007. Retrieved from http://archive.ifla.org/VII/s22/project/GlobalStatistics.htm

Isaac, A., Matthezing, H., van der Meij, L., Schlobach, L., Wang, S., Zinn, C. Putting ontology alignment in context: Usage scenarios, deployment and evaluation in a library case. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 2008; 5021(2008):402–417.

Jamali, H.R., Nicholas, D. Interdisciplinarity and the information-seeking behavior of scientists. Information Processing and Management. 2010; 46(2):233–243.

Jukes, L., McCain, I., Crockett, T. Understanding the Digital Generation: Teaching and learning in the new digital landscape. New York, NY: Corwin Press; 2010.

Knight Commission Report. Retrieved from http://www.knightcomm.org/recommendations/, 2009.

Knorr, E., Gruman, G., What cloud computing really means. InfoWorld, 2008. April 7, 2008. Retrieved from http://www.infoworld.com/d/cloud-computing/what-cloud-computing-really-means-031

Kranich N., ed. Libraries and Democracy: The Cornerstones of Liberty. Chicago, IL: American Library Association, 2001.

Levin, D., Arafeh, S., The digital disconnect: the widening gap between Internet-savvy students and their schools. Pew Internet & American Life Project, Washington, DC, 2002. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/report_display.asp?r=67

Levin, D., Richardson, J., Arafeh, S., Digital disconnect: students’ perceptions and experiences with the internet and education. P. Baker, S. Rebelsky. Proceedings of ED-MEDIA, World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications. Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, Norfolk, VA, 2002:51–52.

Library Council of New South Wales. Retrieved from http://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/services/public_libraries/publications/docs/bookendsscenarios.pdf, 2010.

Long, S.A. What’s new in libraries? Digital natives: if you aren’t one, get to know one. New Library World. 2005; 106(3/4):187.

Mell, P., Grance, T., The NIST definition of cloud computing. National Institute of Standards and Technology, Information Technology Laboratory, ver. 15, 2009. Retrieved from csrc.nist.gov/groups/SNS/cloud-computing/cloud-def-v15.doc

Nicholas, D., Huntington, P., Jamali, H., Rowlands, I., Fieldhouse, M. Student digital information-seeking behaviour in context. Journal of Documentation. 2009; 65(1):106–132.

Oblinger, D. Boomers, Gen-Xers and Millennials: Understanding the new students. EDUCAUSE Review. 2003; 38(4):37–47.

Oblinger, D., Oblinger, J. Is it age or IT: first steps towards understanding the net generation. In: Oblinger D., Oblinger J., eds. Educating the Net generation. Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE; 2005:2.1–2.20.

Online Computer Library Center (OCLC). Retrieved from http://www.oclc.org/research/, 2010.

Osif, B.A. W(h)ither libraries? The future of libraries, part 1. Library Administration and Management. 2008; 22:49–54.

Palfrey, J., Gasser, U. Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Basic Books; 2008.

PEW Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1660/internet-experts-say-aging-millennials-will-continue-personal-disclosure-information-sharing, 2010.

PEW Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org//media//Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Future_of_the_Internet_cloud_computing.pdf, 2010.

PEW Internet and American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1654/wireless-internet-users-cell-phone-mobile-data-applications, 2010.

Portmann, C., Roush, A.J. Assessing the effects of library instruction. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2004; 30(6):461–465.

Prendiville, T.W., Saunders, J., Fitzsimons, J. The information-seeking behaviour of paediatricians accessing web-based resources. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2009; 94(8):633–635.

Prensky, M. Digital natives, digital immigrants part 1. On the Horizon. 2001; 9(5):1–6.

Prensky, M. Engage me or enrage me. EDUCAUSE Review. 2005; 40(5):61–64.

Putnam, R., Feldstein, L.M., Cohen, D. Better Together: Restoring the American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2004.

Pyati, A. Limited English proficient users and the need for improved reference services. Reference Services Review. 2003; 31(3):264–271.

Radford, M.L., Snelson, P. Academic Library Research: Perspectives and current trends. Chicago, IL: Association of College and Research Libraries, A Division of the American Library Association; 2009.

Research Information Network (RIN). Retrieved from http://www.rin.ac.uk/our-work/using-and-accessing-information-resources/towards-academic-library-future, 2010.

Rosen, L. Rewired: Understanding the iGeneration and the Way They Learn. New York: Palgrave Macmillan; 2010.

Ross, L., Sennyey, P. The library is dead, long live the library! The practice of academic librarianship and the digital revolution. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2008; 34(2):145–152.

Rushkoff, D. Playing the Future: How kids’ culture can teach us to thrive in an age of chaos. New York: HarperCollins; 1996.

Sanborn, L. Improving library instruction: Faculty collaboration. Journal of Academic Librarianship. 2005; 31(5):477–481.

Sapp, G. A Brief History of the Future of Libraries: An Annotated Bibliography. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press; 2002.

Saunders, L. The future of information literacy in academic libraries: A Delphi Study. Portal: Libraries and the Academy. 2009; 9(1):99–114.

Shuman, B.A. The Library of the Future: Alternative Scenarios for the Information Profession. Englewood, C O: Libraries Unlimited; 1989.

Shuman, B.A. Beyond the Library of the Future: More Alternative Futures for the Public Library. Englewood, CO: Libraries Unlimited; 1997.

Tapscott, D. Growing up Digital: The Rise of the Net Generation. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1998.

Tapscott, D. Grown up Digital: How the Net Generation is Changing Your World. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008.

Timmers, C.F., Glas, C.A.W. Developing scales for information-seeking behaviour. Journal of Documentation. 2010; 66(1):46–69.

Transliteracy Interest Group of the American Library Association. Retrieved from http://connect.ala.org/transliteracy, 2010.

Tyner, K. Literacy in a Digital World: Teaching and Learning in the Age of Information. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum and Associates; 1998.

Wainright, E., Digital libraries: Some implications for government and education from the Australian development experience, 1996 Paper presented at Singapore, 1996. National Library of Australia Staff Papers. Retrieved from http://www-prod.nla.gov.au/openpublish/index.php/nlasp/article/viewArticle/1004/1274

Wennerberg, U. Using the Delphi Technique for planning the future libraries. Unesco Bulletin for Libraries. 1972; 26(5):242–246.

Wildemuth, B.M. Effective methods for studying information seeking and use. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 1218–22, 2002.

Zoho. Retrieved from http://www.zoho.com/, 2010.