Chapter 9

Make a Guessing Game with Python

Chapter 8 introduces the Python programming language. This chapter explains how to make a simple number guessing game for one player. The player thinks of a number between 1 and 10. Your code guesses the number.

Sounds simple, right?

Not so fast. You have to think about everything that can happen in the game. And you also have to discover more about Python.

Think about Code

Does having to think about code mean you’re a terrible programmer?

No!

It’s good. It means you have to think about what you’re doing. Good programmers do a lot of thinking before they start writing and typing code. They start by breaking a big and complicated problem into small steps. Then they work through the steps.

Good programmers have to learn new tricks all the time. You might think developers already know everything they need to know.

It would be cool if they did. But that’s not what happens.

Software developers have to learn new things all the time. Sometimes this means looking up how to do things in a new language — like Python. Sometimes it means finding out whether someone else has invented a clever answer for a problem. And sometimes it means looking at the code and projects that other developers are working on to see whether you can learn anything from them.

So not knowing where to start is normal. It’s how most projects begin.

Work out what you need to learn

For a project like the one in this chapter, you have to sketch out how your game works in outline, without worrying about clever details.

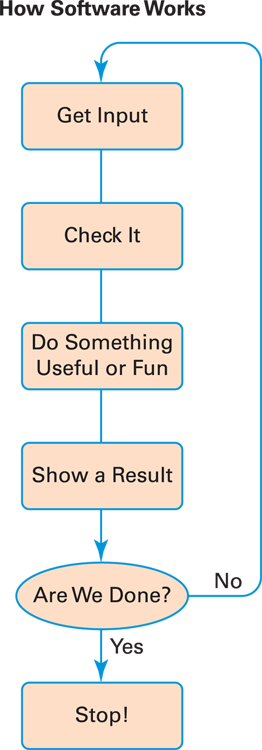

This part is easy. Most computer software has the same shape. It looks like this:

- Ask the user a question, wait for the user to click or tap a button, or load some information from a file.

- Check that the user hasn’t made a mistake.

Do something useful or clever.

For this game, it means working out how to guess a number.

- Show a response and/or save it to a new file.

- Check whether you’re done yet.

- If you’re done, stop; otherwise, go back to Step 1 and go around again.

Most games wait until the user pushes a button on a hand controller or clicks a control on the screen. When something happens, the game responds by updating the position of the spaceship, or the treasure, or the cute talking candy, and maybe increasing the score — unless the spaceship blows up, a unicorn from the other team steals the treasure, or the candy disappears, in which case sound effects and sad music happen, and the player has to start again.

Make a list of things to do

After you have an outline (see Figure 9-1), you can work out what you need to learn. Make a list of your own first, and see how much it looks like the one here:

- How do I ask my player a question in Python?

- How do I get an answer from my player?

- How do I check that the answer makes sense?

- How do I guess a number in a clever way?

- How do I know when we’re done?

- How do I make my code loop back?

- How do I stop?

That’s a lot of questions for a simple game!

But wait! You don’t have to answer them all at once! You can take them one at a time. Suddenly that doesn’t look like such a huge job. It’s still a big job, but it’s not impossibly planet-sized in a too-big kind of a way.

Breaking down one hard problem like “Make a cool game” into lots of simple problems like “How do I stop?” is the only way to go. Trying to get all the parts of a game working as you type is like jumping into an alligator pit and trying to fight all the alligators at once with one hand tied to a mouse and the other tied to your head.

Taking things step by step means you can write code for each question without worrying about the other questions.

Doing everything at once will only confuse you, and give the alligators an unfair advantage. You don’t want that — even if you like alligators.

Ask the Player a Question

How do you ask the player a question in Python? How do you find out how to ask a question?

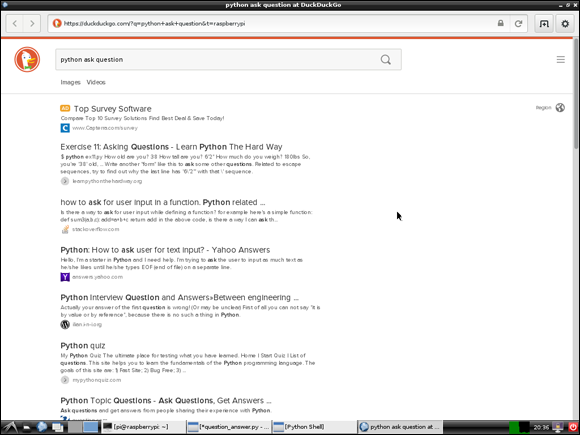

Search on the web! Open the Epiphany web browser on your Pi — see Chapter 5 for details and type Python ask question into the search bar at the top. Figure 9-2 shows the results you maysee. (You may not get exactly the same results, but you should see similar hits.)

Search engines are kind of dumb, and they don’t understand English questions. They just look for important words, so you can leave out words that don’t matter, like a and the and of. And you get better answers by putting the most important word first. In this example, that’s Python. That’s how you get “Python ask question.”

Using raw_input

Take some time to look through the top hits. Do you see how to ask a question and get an answer now? Searching the web tells you the answer: You can use a Python command called raw_input to get an answer from a user.

You need to add some code that looks something like this:

player_answer = raw_input(“Question: yes or no?”)

Test your new skill

It’s always good to test code as you go. Sometimes it’s easier to write a test as a small side project.

To test your question-asking code:

- Choose File ⇒ New Window to open a new Editor window.

Type the following:

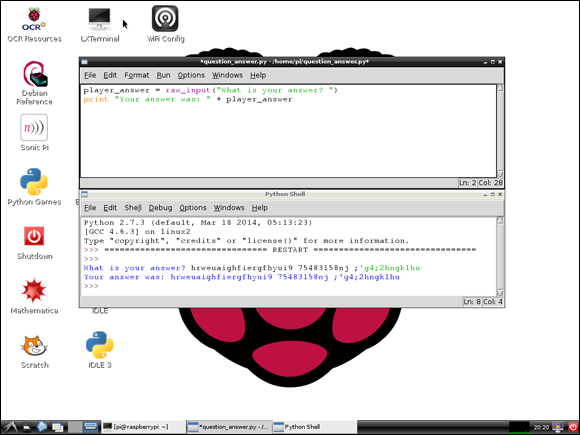

player_answer = raw_input("What is your answer? ")print “Your answer was: “ + player_answerSave the file as question_answer.py and run it.

If you didn’t make any typos, you should see something like the messages in Figure 9-3.

raw_input doesn’t care what the user types. It’s like a dumb robot. If you type a load of gibberish, it saves the gibberish in the player_answer variable.

The next line in the code prints out whatever is in player_answer. It doesn’t care if it’s gibberish either.

But hey, you’ve ticked off two whole items on your to-do list! You know how to ask the user a question and how to get an answer.

Working out whether the answer makes sense is a different problem.

This is why it’s so cool to break any big project into lots of teeny problems. You can make progress by working on them one at a time.

Check the Answer

To check whether an answer makes sense, you need to know the difference between a good answer and a bad answer.

In this example, you’re making a guessing game, so to keep it simple, you want very simple answers to questions — yes or no. If the player types anything else, your code should ignore it.

But it can’t just ignore it and carry on. It has to keep asking the question over and over until the player types yes or no. So the check has to include a test that loops back to ask the question again until it gets an answer that works.

Now you have to replace one old problem (How do I check the answer makes sense?) with two new problems:

- How do I check whether an answer is yes or no?

- How do I keep asking the question until the answer is yes or no?

Isn’t that more work? Yes, it is. But you often have to keep splitting a problem into smaller problems. It’s not unusual to find that your project to-do list gets bigger for a while as you work through it.

It gets smaller eventually. Promise!

Check for yes or no

If you spent some time playing with Scratch, you’ll know there are two ways to check whether something is true. You can use if , like this:

if something is true

do a thing

else

do some other thing

Or you can use repeat…until, like this:

repeat

do a thing

until

some test is true

if solves half the problem. You could use it to check for yes or no, but it doesn’t give you a way to keep asking the same question over and over.

repeat…until sounds perfect. It checks and loops at the same time, like this:

repeat

answer=raw_input("Question…")

until

answer = "yes" or answer = "no"

The question keeps appearing until the answer is yes or no. Perfect!

But, uh, unfortunately, Python doesn’t understand repeat…until.

Also — wait a minute… .

Doesn’t

answer = "yes"

mean you’re saving a value of yes in the answer variable? That’s not much use as a check, is it?

Check for anything at all

You have to know the magic word to check whether two things are the same. The magic word is two equals signs instead of one, like this:

repeat

do really cool stuff

until

answer == "yes" or answer == "no"

Why? This is one of those times where it just is. It’s a magic word, and you have to know it. That’s all.

Go around and around …

So that’s half the problem solved. What can you use in Python to do the same job as repeat…until?

If you do a web search, you’ll see it’s called while. It works like this:

while [include a test here]

do cool stuff

do more cool stuff

carry on from here…

Cool stuff happens over and over while the result of the test is true. The code keeps doing the cool stuff until the test is false/not true. Then Python moves on to whatever happens next.

Problem solved? Nearly. But not quite.

Check for opposites

Here’s a question for you: When should the code loop? What tests should you put in while?

Look at Table 9-1 to help you guess.

Table 9-1 When Should My Code Loop and Ask Again?

Is the Answer Yes? |

Is the Answer No? |

Should I Ask Again? |

Yes |

Doesn’t matter |

No |

Doesn’t matter |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes! |

The code should loop while the player’s answer isn’t yes, and it isn’t no.

How do you check whether something isn’t equal to something else? You need another magic word. It looks like this:

if answer != “yes”

In English, when you see != you say not equal. So the code checks whether the answer is not the same as, not equal to, and generally different to yes — which is exactly what you want.

The while test looks like this:

answer = raw_input(“Question: yes or no? ”)

while answer != “yes” and answer != ”no”:

answer = raw_input(“Question: yes or no? ”)

You have to set up the test to fail before you go into the loop, to make sure raw_input happens at least once. You could make it blank, but it’s just as easy to ask for some useful input and check it.

Add colons and indentation

You also have to put a colon (“:”) after the test. Python needs to see a colon after every test in your code. (It’s another of those “Because reasons” magic word features.)

When you end a line with a colon, the Editor automatically, at no extra cost to you, indents the next line, adding a gap of a few spaces at the start.

Python uses the extra spaces to remember that the indented code goes under the while. If it didn’t do this, it wouldn’t know which code to skip after the while, and it would get very confused about what it was supposed to do.

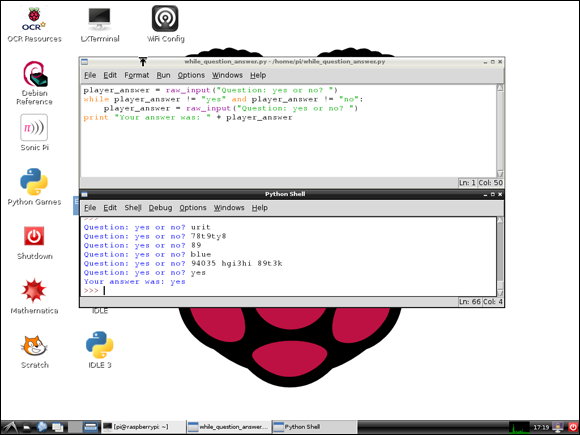

Figure 9-4 shows a slightly remixed and expanded version of the same code. The variable is called player_answer for clarity, but it works just like the code on the previous page.

As you can see, you can type any old nonsense and the code keeps asking you for yes or no, relentlessly, like a Terminator robot. It gives up only when you enter yes or no.

Woo hoo! It works! But that was a lot of work for a simple thing, wasn’t it?

It’s normal for software to spend a lot of time checking the input. Humans are unpredictable, but good software can handle every possible thing a human might do. This can take a long time to get right because there are soooooo many possibilities.

Repeat Questions

The code is almost ready to start making a simple version of the game. You could make it ask questions like this:

Think of a number between 1 and 10!

Is your number 1 (yes or no)?

Is your number 2 (yes or no)?

Is your number 3 (yes or no)?

And so on for all the other numbers, up to

Is your number 10 (yes or no)?

This version of the game always guesses the right number. It’s not very interesting, magical, or fun. But it works.

It’s fine to make code do simple not-quite-finished things, especially while you’re learning new stuff. So think of this early version as a super-secret experiment. You don’t have to show it to anyone. Getting it working is still an achievement to be proud of, and you can add extra cleverness and magic later.

Count to ten

How do you count to ten? There’s more than one way to make your code do this. You could put another while loop around the code, starting with a guess of 1, adding 1 to the guess each time, and breaking out of the loop when the guess is 11.

But if you’ve played with Scratch, you know a different way, called a for loop. Unlike a while loop, a for loop includes a variable that holds a count. The counter works automatically. Every time your code goes around the for loop, the value in the counter gets bigger by one.

Use range in Python

for loops in Python are slightly weird. Instead of saying “Start from this number and end with that number” you have to give Python a range.

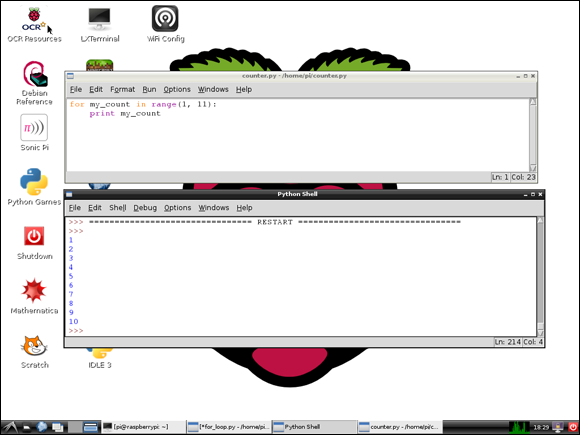

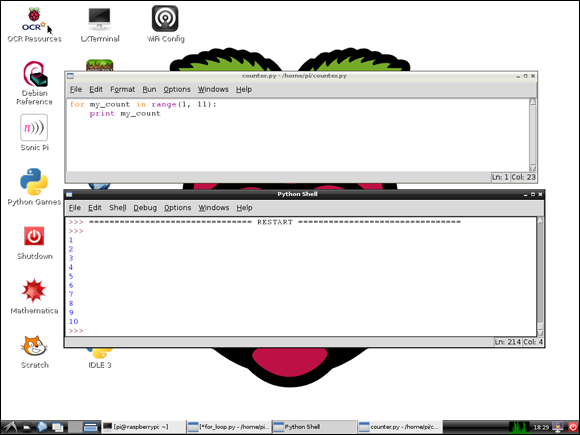

Here’s an example that counts from one to ten:

for my_count in range(1, 11):

print my_count

This is almost easy to understand. In English, it would say, “Count from the start of the range (1) to the end of the range (11) and print the count each time through.”

But why is the last number of the range 11 and not 10? Because reasons! This is another of those things in Python that doesn’t really make sense. You just have to remember that when you use a for loop, the end of the range is always one more than you’d expect.

Figure 9-5 shows that you can now count to ten in Python.

Stop the count early

What if you want to stop the count early? What if your game guesses the number before reaching ten?

You can jump out of a for loop with a magic word called break, like this:

for my_count in range(1, 11):

print my_count

if my_count == 4:

break

When my_count is 4, the for loop screeches to a halt with the sound of squealing brakes and the smell of burning rubber.

Not literally. It would be fun if it did. But no.

However, it does stop early. Sometimes that’s what you want.

Figure Out Variable Types

Remember, you can’t do math on text. And you can’t join numbers together to make words and sentences.

This means not all variables are the same. And this won’t work:

for my_count in range(1, 11):

print “This number is: “ + my_count

When Python prints a single variable, it makes a best guess about what you want to see. You can use print with a number, or with text, and it works fine.

But Python is kind of dumb. It isn’t smart enough to glue text to a number and make it work. So when you try to print text and a number on the same line, Python has a meltdown and sulks.

Just to confuse you, you can remember numbers in Python in two different ways. You can remember them as whole numbers, which is a good way to count things or say “The fifth item in a list.”

Or you can go the whole shebang and remember them with a decimal point, which is the right option when you need to do serious math.

Python also remembers text. Text is just letters, spaces, and all those weird characters on your computer keyboard.

These three ways to remember data are so useful they have their own names. Tables 9-2 and 9-3 list them for you.

Table 9-2 A Few Variable Types

Type Name |

Example |

Used For |

int |

10 |

Whole numbers only |

float |

3.14159 |

Numbers with a decimal point |

string |

“text” |

Letters, words, and sentences |

Here’s something you need to remember: All the types do math differently. You can’t do math on strings, but you can use + to glue one string to another to make a longer string.

float math just works. int math is weird. You can add, subtract, and multiply just fine. But if you divide one int by another, you only get the whole number part of the answer. Any fractions or decimals disappear!

Table 9-3 Math You Can Do

Type Name |

Math You Can Do |

Example |

int |

Whole number math only (division rounds down) |

5 / 2 = 2 |

float |

All math |

5 / 2 = 2.5 |

string |

“+” only |

“a” + “b” = “ab” |

Convert types

It would be really useful if you could convert between the types. And you can! Python includes a toolkit that does exactly this. Table 9-4 shows you.

Table 9-4 Converting Types

Conversion Code |

What It Does |

Example |

int(variable) |

Makes an int |

int(5.9) = 5 |

float(variable) |

Makes a float |

float(5) = 5.0 |

str(variable) |

Makes a string |

str(1) = “1” |

Print text and numbers

You can make the example in the “Repeat Questions” section work. Add str() around the counter variable, and suddenly you can combine a number with text:

for my_count in range(1, 11):

print “The count is: “ + str(my_count)

Put the Guessing Game All Together

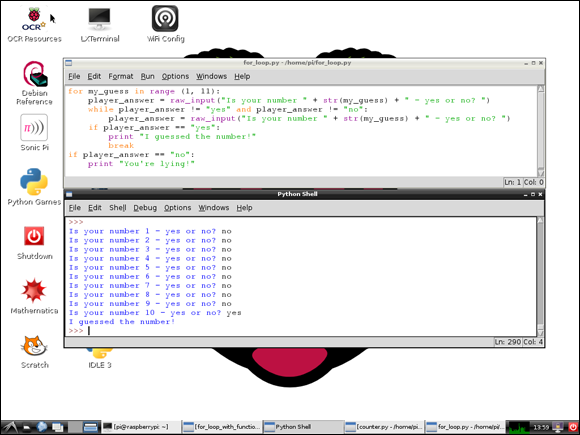

Now you can sketch out the simple version of the guessing game, like this:

- Use a for loop to count from 1 to 10.

- Show the current guess.

Ask the player to type yes if it’s right or no if it’s not.

Keep asking until the player types yes or no.

If the player said yes, print “I guessed the number!”; otherwise, go back to Step 2 and allow the loop to try the next number.

What happens if you get to 10, and the player hasn’t said yes? Obviously, this scenario is impossible, and the player is a bad person who lies to computers. So you can add one last step:

- If the guess gets to 10 and the player hasn’t said yes yet, call the player a liar.

You should know enough about Python now to write the code to make this happen. To save time, here’s one possible answer.

for guess in range (1,11):

answer = raw_input(“Is your number “ + str(guess) + “ – yes or no? “)

while answer != “yes” and answer != “no”:

answer = raw_input(“Is your number “ + str(guess) + “ – yes or no? “)

if answer == “yes”:

print “I guessed the number!”

break

if answer == “no”:

print “You’re lying!”

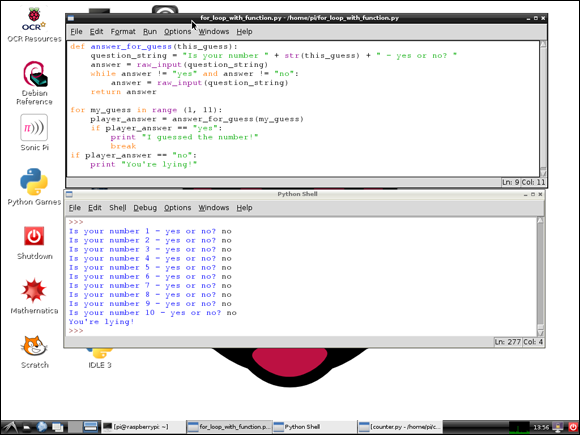

Figure 9-6 shows how it works on the Pi.

Repeat Code and Make It Simpler

The code works, but it’s kind of complicated and hard to read.

Good code is easy to read, but this code has a lot of detail on some of the lines. And some of the code is repeated.

Repeats are bad because they mean the code isn’t as neat as it could be. They also make it harder to change the code. If you change one repeat, you have to change them all. But it’s easy to forget a repeat or to make a mistake.

So this code is more likely to have bugs — mistakes — than simpler code. And as you keep adding to it, you’re more likely to add more bugs.

Python has a neat way to deal with repeats. You can wrap your code inside a function.

Find out about functions

Functions can have four ingredients, although they don’t always need them all:

- A name

- Input variables

- Code to repeat

- A way to return a result

You don’t always need the input — for example, if you write a function to tell the time, it doesn’t need to be told the time. (Duh.)

You don’t always need to return a result. But you do always need a unique name, and some code that does something.

Make and use functions

To make a function, you use the magic word def, like this:

def my_function(input variables):

[clever code for the function goes here]

return output

To use the function, type this:

some_value = my_function(input)

This runs all the clever code, but the function code stays in one place. You also can use it over and over by typing a single line whenever you need it in the rest of the code.

Decide what to put in a function

When you split some code into a function, you want to make the rest of the code easier to read, and you also want to create a block of code you can reuse. Either option is good, but if you can get both, that’s a total win.

In this game, it’s hard to read the lines with raw_input. You can fix this in two ways.

You can put each raw_input line into a function and use the function to replace it.

Or you can take the entire answer block of code and put that into a function, like this:

for my_guess in range (1,11):

answer = answer_for_guess(my_guess)

if answer == “yes”:

print “I guessed the number!”

break

if answer == “no”:

print “You’re lying!”

That’s a lot easier to read, isn’t it? If you remember about breaking down a big problem into smaller problems, you can use functions to help you.

This also means you can sketch out code as a list of functions and then write the code inside them later!

Write a guess function

You’re almost ready to write your first function. You need to know that the def section goes at the start of the code.

And there’s one more thing you can do to make the code simpler. You can put the question string into a variable so that you can repeat it without having to retype it. You don’t need to write a function to do this because the string doesn’t do any processing.

Figure 9-7 shows how it works:

def answer_for_guess(this_guess):

question_string = “Is your number “ + str(this_guess) + “ – yes or no? ”

answer = raw_input(question_string)

while answer != yes and answer != no:

answer = raw_input(question_string)

return answer

Add Smarts and Magic

There’s a secret rule of software design that no one will tell you: Good software seems smarter than you are; bad software seems dumber than you are.

Software is like stage magic. If you can see how the tricks are done, it’s kind of disappointing. But if you can’t, it’s a lot more impressive. And if it’s really good, it almost looks like real magic.

So far, this game is not smart. How can you make it smarter? You need a better way to guess numbers. Anyone can count through them one by one.

Can you think of a better way? You could try numbers at random instead of counting — like throwing a ten-sided dice for each guess. But that will take just as long, and you’ll have to do a lot more work to put your guesses in a random order.

Developers spend a lot of time working out clever and fast ways to do things like sorting and searching through numbers and words. If you’re very good at computers, you can guess some of the simpler recipes (algorithms), but most people have to look them up in books or online.

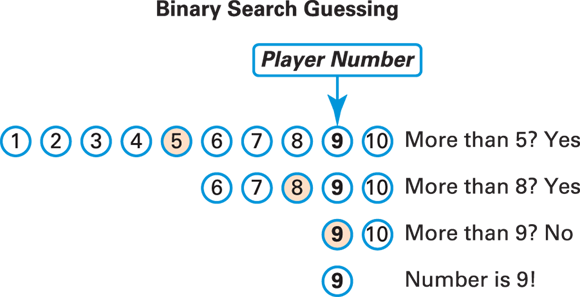

For a problem like this, a good algorithm to use is called a binary search. A binary search sounds complicated, but it’s a simple idea. You put your first guess in the middle of all the possible numbers, and you ask your player whether the guess is high or low.

Now you have only half as many numbers to search through. That’s a neat trick. So why not do it again? Split the remaining range in half and ask whether your guess is high or low.

Eventually the range shrinks to either two numbers or three numbers. If you have two numbers, you can check the higher one. If it is — boom! You’re done. If not, it’s one less.

If you have three numbers, you can check the middle number. If the guess is too low, you know it’s the top number of the three. If not, you’re down to two numbers and you can repeat the recipe from the previous paragraph.

You always guess the number, and you always do it in four or five tries. Figure 9-8 shows one example.

Can you write the code to improve the game with a binary search? There’s a sample answer on the website for the book, but try to create your own answer first. Take as long as you need. If you get lost, try to break down the problem into simpler subproblems and work through them one by one.

In computer-land, information from the outside world is called the input. The software takes the input, and after doing clever things to it, it produces an output. Information in general is called data, which means whatever you’re given to work with. Doing something clever is called processing the data. So the short version of the loop is input⇒processing ⇒output.

In computer-land, information from the outside world is called the input. The software takes the input, and after doing clever things to it, it produces an output. Information in general is called data, which means whatever you’re given to work with. Doing something clever is called processing the data. So the short version of the loop is input⇒processing ⇒output.

Some books about software list the code you should type, and then — if you’re lucky — they explain a little about how it works. Doing it this way looks easy, but it doesn’t teach you how to write your own code. Asking questions and thinking first looks much harder, but once you get over the scary part at the beginning, you’ll write better code more quickly, and you’ll be less likely to get stuck.

Some books about software list the code you should type, and then — if you’re lucky — they explain a little about how it works. Doing it this way looks easy, but it doesn’t teach you how to write your own code. Asking questions and thinking first looks much harder, but once you get over the scary part at the beginning, you’ll write better code more quickly, and you’ll be less likely to get stuck.

Why not search for Ask a question in Python? Sometimes full English questions work just fine, but sometimes they confuse the search engine, so it’s better not to use them while searching.

Why not search for Ask a question in Python? Sometimes full English questions work just fine, but sometimes they confuse the search engine, so it’s better not to use them while searching.