Chapter 6. Managing Conflict

There can be no change without conflict. Read that sentence again. It’s that important.

Disagreement, controversy, and conflict are the most formidable challenges you’ll face as a rebel. There are ways to manage controversy, but there are no ways to avoid it. Great outcomes involve some kind of controversy.

You’ve no doubt experienced the struggles that go with having unusual and unpopular views. You may have been in a messy, controversial situation and didn’t know how to turn it around. The messiness was overwhelming and the stress was horrible. Some of you may even have been in the awful situation of being thrown under the bus when your tireless efforts on behalf of a good idea got you tangled up in a major conflict at work. Good ideas are rarely welcomed without disagreement or controversy.

In this chapter, we’ll share some useful ways of minimizing conflict and preparing for it, and tactics to use when it erupts. Of all the chapters in this book, this is the one that we most wish someone had given us when we were starting our careers.

Our concern for others and not wanting to be seen as mean are among the key reasons why many of us have such a hard time with conflict. The more skilled we are with conflict, the less afraid of it and the more powerful—or, better yet, influential—we become. Meanness has nothing to do with it.

Note

When you get into interpersonal conflict at work, the best default is empathy. Arguments based on logic lead to an impasse or even more ill feelings.

Three Stages of Conflict

We break conflict into three stages: disagreement, controversy, and conflict itself.

A way to understand these three stages is to look at how strategically important your rebel recommendation is to the organization and how complex the issue is. The more strategically important the topic and the more complex the decision, the more likely it will escalate into conflict. If it’s not that important and is relatively easy to resolve, things will likely stay in the less heated, less dangerous disagreement territory. It’s important to know where you are—disagreement, controversy, or conflict—because there are different tactics and considerations for each stage.

Here are some of the characteristics of each stage:

- Disagreement

- Talking about ideas. Differing views and approaches surface, often during routine meetings and casual conversations.

- Controversy

- Considering new ideas. When disagreements over new ideas lead to the emergence of semi-official positions, controversy emerges. This is a moment of opportunity because people are paying attention to our ideas.

- Conflict

- Fighting about new ideas. When controversy turns into an issue or a fight, this is conflict. One (or both) sides want to win, and someone will lose. It’s the most emotionally fraught stage and where we often face our moment of truth.

Disagreement: Talking About Ideas

Most people aren’t comfortable in intense and challenging conversations. What rebels consider interesting conversations others often see as uncomfortable disagreements. When someone suggests having an “open, honest dialogue,” we take that person at his word. “Yes, let’s have the real conversation at last,” we think and jump right in with our views. Before you know it, we’re engrossed, asking provocative questions, sharing our observations, questioning assumptions, suggesting alternatives—and quite possibly alienating that person because we’re coming on so strong.

So how can we disagree without being disagreeable? Learn from others by really understanding their views? Talk about our different point of view without coming across like we’re attacking the other person?

When you’re in a meeting or conversation:

- Listen before jumping in.

- Listen more than you speak, and err on the side of being positive, not combative.

- Remember that it’s not about winning.

- Disagreeing and debating ideas is not about being right; it’s about creating understanding and learning. The objective is achieving clarity, not achieving victory.

- Take out the emotion.

- Open with “Here’s what I’ve observed…” rather than with “I think that…” This takes the personal emotion out of the statement; it’s not about you but about the evidence. Inviting people to comment on observations—not you—makes them feel more comfortable expressing their views. You might even try asking questions and making comments without using any pronouns whatsoever (no “I” and no “you”). For example, “What contributed to the situation?” and “What alternatives are there?”

- Speak last.

- Be the last person to speak at a meeting, and ask a question instead of making a statement. Try it a couple of times to see how it feels. This shows people that you’ve listened and heard them. The thoughtfulness of your questions shows your understanding of the topic without having to say much. And you might learn something critical.

Good questions are a rebel’s friend. They help us learn, research, seed doubt about prevailing assumptions, invite people to consider possibilities, and gauge how much energy exists for creating or resisting change. Unlike statements like “I don’t agree with that,” questions are less likely to be perceived as oppositional. (Unless, of course, the situation really needs some frank straight talk at that moment.)

When you’re leading a meeting:

- To assess importance or urgency, ask them to rate it.

- How important do you think this issue is on a scale of 1 to 10? Or how valuable do you think that direction would be on a scale of 1 to 10? Asking for a rating helps surface importance. If no one thinks it’s all that important, don’t waste your energy and reputation capital disagreeing about it.

- To keep the conversation positive, frame it in terms of appreciation.

- Where has this approach worked well before? What are the upsides of going in this direction? What would success look like to you? What would be the very best outcomes for you? When you engage people with a positive mind-set, they become less defensive and more open-minded.

- To focus on possibilities and collaboration, ask, “How might we?”

To move a conversation away from problems associated with your idea, ask a “How Might We” question. How implies there’s a solution. Might makes it safe to suggest ideas that may or may not work. We means that we’re in this together and are trying to collaborate for the good of the organization.

For example, if someone says the project is too risky to consider, you could ask, “How might we reduce risk and be more daring?” Or, if the resistance is about resources, you could say, “How might we get this new idea off the ground with our existing resources?”

How Might We questions are expansive and inclusive. They breathe fresh air into a stale, tension-filled meeting. They get people back to thinking about possibilities, and out of the negativity of disagreement.

- To keep people from feeling defensive, avoid why questions.

Asking why questions during disagreements can make people defensive. Why can be seen as interrogating a person, whereas what asks about the situation.

Consider the difference between these questions:

- “Why do we always disagree about this issue?”

- “What is it about this issue that evokes such strong emotions?”

The first is about personalities; the second focuses on the issue and puts us on less emotionally volatile ground so that we can have a conversation and work things through.

Disagreement is essential to learning what people think, feel, and want to see happen (or not happen). It can clarify thinking and create shared understanding. Often when there’s a difference of opinion, people don’t know whether they really disagree, whether they have different information or different values, or whether cognitive bias is coloring their perspective. It’s incumbent upon the rebel at work to clarify this for everyone at the meeting. Try to gently surface the reasons behind the disagreement.

We also believe that the most constructive disagreements happen when we’re friendly, not defensive, listening for others’ ideas and listening to what they have to say without simultaneously thinking about how to rebut their points.

Warning

If you feel yourself getting upset during a disagreement, shut your mouth. Err on the side of saying nothing when you feel like lashing out. The angrier you feel, the quieter you should become. Really. You’ll find more on anger and its relationship to conflict later in this chapter.

Let’s turn now to controversy, which kicks the potential danger, necessary preparation, and potential for change up a notch.

Controversy: Considering Ideas

If your idea truly challenges the way things have always been done, you will engender controversy. Controversy means people have begun to pay attention and think your idea might be interesting, which is a good thing.

Controversy Is Necessary for Change…

Real change often entails controversy. If an idea doesn’t generate controversy, it might not be as strong as it could be. If it’s really important, some people will disagree with it, if only because they don’t yet fully understand it. If everyone agrees on a proposal, is it too similar to what exists? Are you missing an opportunity?

Note

Think of controversy as the necessary mating ritual before various good ideas can give birth to progress.

…But That Doesn’t Mean We Like It

We suspect that some of you are thinking, “I don’t like the way this is going. I don’t know if I can sign up for controversy and conflict.” But you can’t run from it. How you handle controversy will determine how your proposals and in fact your entire career will fare. These moments of controversy offer us opportunities to gain new allies, better understand our opponents, and find ways to improve our ideas. They may also provide insight into intractable organizational values that we may never be able to change.

No matter where we are on the conflict spectrum, there are some days we would all rather go with the no-controversy proposal, get buy-in, and move on. Resist this temptation. Good ideas need good controversy, and we need good ways to manage it.

Here’s Where Your Work Pays Off

When you enter the zone of controversy, you’ll see the benefits of all the hard work you did mastering the organizational landscape. If you were thorough, you will have anticipated most of the major points of controversy. If you took shortcuts, you may very well find yourself ambushed by the bureaucracy and outmaneuvered at the conference table.

You’ll find a lot of details in this section. That’s because in our experience most rebels find themselves in this position and need tactical help and forethought to navigate it well.

Rebel strategies for dealing with controversy build upon many of the same best practices for communicating ideas covered in Chapter 5. Those communication strategies will help you throughout your rebel journey, but navigating controversy will require you to learn some new Jedi moves. Most of the time, we will succeed not through brute rhetoric, but by being better prepared and more mindful than our colleagues.

Some Rebel Don’ts

As your rebel coaches, we have some ground rules to lay out before we tell you how to prepare for a controversial meeting:

- Don’t go it alone.

- Rebels are always at risk of wearing out their welcome, and we are never more vulnerable than when advocating for controversial ideas. Our colleagues grow tired of just hearing us speak, never mind our ideas. It’s a sound strategy to find others who can articulate the change agenda or speak on behalf of our proposals. It makes sense to have these individuals attend key meetings where they can mediate or observe the dynamics more dispassionately than we can.

- Don’t hide known weaknesses.

- We sometimes make the mistake of packaging our ideas in ways that hide known weaknesses. Smart executives love to ask the question we hope will not be asked. Don’t go into a meeting with a presentation designed to conceal or avoid points of disagreement; it will come back to bite you. You will lose credibility and trustworthiness, which will hurt your chances of selling your proposal and damage your professional reputation. You will forfeit more than the potential success of your idea.

- Don’t dismiss objections.

- When your colleagues object to your proposals, it means you have engaged them in a significant way. Understand their concerns; don’t minimize or dismiss them. Sometimes what really damages us is not so much the controversy but the impression that we don’t really understand others’ objections. When someone expresses a concern, acknowledge the importance of the point and ask for suggestions in dealing with it. If the person responds, you may have begun the process of turning an opponent or skeptic into a potential ally.

- Don’t monopolize the meeting.

- As a rule, presenting your proposal should take up about one-third of the meeting, and the discussion—which you will guide—should take the other two-thirds. Carefully monitor your share of the conversation time. There is no worse outcome than the “other side” feeling that they did not receive a fair hearing.

- Don’t focus on the who; focus on the what.

- When you wade into controversy, focus the debate on issues, not personalities or value systems. There is nothing to be gained from pointing fingers. When conversations descend into drama, people’s minds shut down and they find it difficult to consider ideas and possibilities. So try to stay out of drama.[5]

- Don’t be absolutist.

- Stay away from hard edges. Do not present yourself as the ultimate arbiter of truth. Introduce your ideas with phrases like “What I have observed is,” “Have you thought about,” or “Here’s how I think about it.” Statements that are absolutist predict the future with finality. For example, “If we don’t make these changes, we will go out of business.”

- Don’t debate the unknowable.

Avoid going down the rathole of debating the unknowable. Some decisions are based on what’s known or can be researched. Others, especially innovative ideas, live in the unknowable. By recognizing that something is unknowable, you can get away from debating “what if.” You just don’t know.

Make sure discussions don’t get mired in the “yes it does, no it doesn’t” madness that characterizes unproductive arguments.

- Don’t wing it—ever!

- Be prepared by storyboarding the meeting and planning as much as possible in advance.

Making Controversial Meetings Productive

Your mind-set is half the battle. Being prepared is the other half. Now that we’ve shared the rebel don’ts, here are success strategies for making controversial meetings as productive as possible.

Be prepared, and get help from allies

Before going into controversial meetings, get together not only with your allies but also with those colleagues who just want to make sure that the meeting is productive. (These people exist—they can be the secretary to the executive committee or the chief of staff for an important executive.)

Imagine how the conversation might unfold and what kinds of objections or concerns will be raised. Think through how you should handle such objections—not necessarily how to defeat them but how best to explore the issue for the benefit of clarity and progress. And be sure to identify exit ramps so that you avoid ultimatums, unnecessary conflict, and perhaps even defeat. For example, what are you willing to trade or concede for partial progress? What halfway outcome are you willing to accept? How do you prevent the issue from getting kicked upstairs? (Our experience is that this is rarely a good outcome for rebels at work.)

Show the so-what

When you engage in controversy, you will be most successful standing up for structural ideas that support the organization’s goals and values. You are advocating for positive change that supports what the organization believes is important.

Show what’s at stake by framing the idea in terms of what really matters. Show how your idea for change links to a core value, shared belief, or important story at work, such as protecting the organization’s reputation for integrity, saving government money, protecting people on the front lines, getting predictable results, or making the organization less vulnerable.

Paint a realistic picture

Paint a realistic picture of what could be. Show that the idea can work. The key verb here is show. Once your idea becomes controversial, assertions that it will work are not sufficient or persuasive. Find examples in which others succeeded by overcoming similar obstacles. Focus your examples on the implementation issues. Talk about another organization that successfully navigated uncertainties and obstacles similar to what your organization will face. This will be more meaningful and persuasive to the group than an abstract painting of the beautiful end state you aim to achieve.

On more than one occasion, we’ve gained credibility by surprising people with practicality. It’s important to have ideas that are firmly grounded in reality.

Make the meeting long enough

Make sure the meeting is long enough for what you want to accomplish, but not too long.

If this is the first time you’re presenting an idea and it’s a big, important idea requiring serious consideration and healthy debate, consider blocking off two to three hours instead of the typical hour-long meeting, which is really only 50 minutes by the time people get settled. A substantive, controversial meeting is a terrible thing to cut short. It takes time to explain your proposal and for people to wrap their minds around the possibilities. You don’t want to rush good thinking, especially on a controversial topic.

When You Are in the Arena (AKA the Meeting)

Now, rebel matador, you are ready to enter the arena with the bulls, the arena we at work call the meeting.

Before you go into the arena, remember that keeping meetings conflict-free is not your goal. If what you’re doing is important, people should object and argue with you. The way ahead often has poor signage.

We’re too often taught in bureaucracies that conflict in meetings is bad and that we should seek consensus. Remember, consensus is not a decision-making strategy. In fact, it is the opposite. It’s a technique to avoid making difficult choices. That said, work hard to make sure the conflict is about the right issues, the ones that really matter.

Note

Building consensus. A stall tactic to avoid making decisions.

Take a deep breath

Before you go into a meeting, take 10 seconds to breathe and decide how you want to show up at (versus in) the meeting, including how you want to feel. Ask yourself: what would the best outcome be? Choose one word as your keyword to recall this vision. Here are some ideas: productive, constructive, intentional, lively—even adventurous.

Explain the focus of the meeting

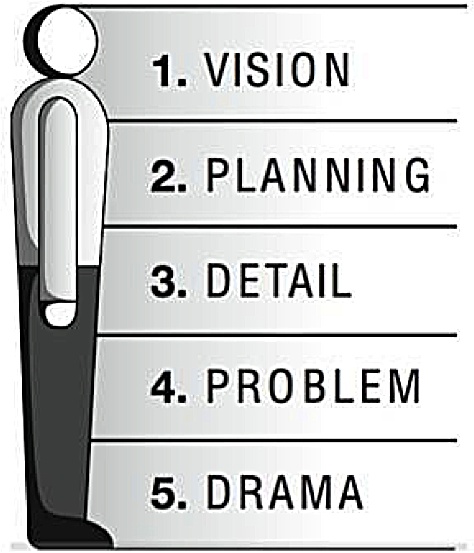

Start by sharing the intent of the meeting and why it matters. (Even better, put that intent into the agenda you send out with the meeting invitation.) The more controversial the topic, the more important it is to create this clarity. One especially useful technique is to put the graphic shown in Figure 6-1 up in the meeting room.

Explain that the focus of this meeting is to talk about a vision for your particular “what’s at stake” issue, so you want to focus the discussion today on vision. Explain that today’s meeting is not about planning how to implement the proposal, delving into the details of how it would work, or exploring what could go wrong.

Make a productive statement like the following at the beginning of the meeting: “If I see that we’re losing our focus in the meeting, I’m going to step in and get us back on track. We want to make the best use of our time. Does that work for everyone?”

We’ve never heard of people saying no to this request. When they agree, you’ve just earned more power and control before the meeting even begins. If people start attacking your proposal and dragging it down into the weeds of detail, drama, or even problems, you can politely point to the visual. Remind the group that everyone agreed to focus on the vision and value of the proposal and suggest a way to get back on track with your agenda.

Establish some ground rules

In addition to agreeing to stay focused on vision, we like to suggest participants agree on ground rules at the start of a session and post them on a wall. Again, people usually appreciate some rules for good conduct, and it helps focus attention on our ideas, not the controversy around the ideas. Some agreements we find useful are:

- Judge ideas, not people.

- Focus on solutions and ways forward; stay away from drama and problems.

- Observations are more useful than opinions.

- Let everyone complete their thoughts; avoid interrupting.

- Ask questions that illuminate, not interrogate.

- Ask questions that are brief and to the point without adding background considerations and rationale, which turn the question into a speech.

- If you want your views to be heard, speak now, not later in backroom side conversations. If the “real” conversations happen after the meeting, it breeds distrust.

After presenting your idea

So now you’ve presented your idea, including the objections you anticipated. If you followed our guidelines, some two-thirds of the meeting should still be ahead of you. It’s time for discussion.

People come to support ideas by discussing them, not from hearing a presentation alone. You want to give everyone time to express their concerns, you want to be able to ask lots of questions to gain clarity, and you want time to end well.

Ask people what they like about the proposed idea immediately after finishing your presentation. When people are in a positive place, they are more open-minded. Help put them in a positive place by asking this question first.

Hear everyone out, acknowledge their points, and reiterate your stand with grace as well as strength. It is wiser to present your view without slamming other people’s ideas. Keep your head above the battle. In fact, if you find yourself on the attack, stop immediately. When we attack, we only hurt our reputation, our good ideas, and the credibility and trust we worked so hard to gain.

Ask for participants’ advice on how to make the idea work. Ask them what they think the next step for the proposal should be. Trust that other people can come up with solutions, too. Then when you share yours, look for the win-win solution by finding common ground to combine ideas.

Discuss for the purpose of achieving clarity, not to win and score points. Listen to others’ points. Respond to them in straightforward ways. Pose interesting questions to your critic: “What frightens you about this issue? What other ways might we be able to address this issue? What in the proposal do you think is worth consideration? Which of the points most concern you?” Ask interesting questions of your supporters as well, such as, “What part of the proposal or situation might be worth zooming into?”

Ending well

To end well, make sure you stop 15 minutes before the meeting is scheduled to end. (We recognize that this is difficult to do, but this is a magical time, not to be short-changed. Some of the most useful insights and real issues come out during this wrap-up.)

Use this time to summarize what people liked about the proposal and their concerns. Then go around the room and ask each person to conclude by briefly sharing one or two comments: “What did you find potentially most valuable about this proposal? What do you think the next step should be?” No one comments on what anyone else says. It’s a way of ensuring that all voices are heard—not just the extroverts or negative BBB types—and provides a clear understanding of the whole group’s perspectives on the proposal.

One last thought. Pay attention to what’s happening as the meeting breaks up. We’ve both been amazed by the fascinating and useful observations people make when they stand up to leave a meeting. In some cases, the people who have been quiet during the meeting will only speak up at this time. We pay close attention to them when the session ends. In all cases, many appear to feel that they can be more informal and share what they really think when the meeting is officially over.

What You’ll Gain

We can’t say that conversations about controversial ideas will always go smoothly (if only!). However, the more prepared you are, the greater the likelihood that you will be heard and that you will learn what is necessary to keep moving your proposal forward. The more prepared, gracious, and respectful you are toward people who don’t share your views, the more you establish your reputation as a credible professional to be taken seriously. As rebels, we can spend too much time thinking about our ideas and not enough time planning how to discuss them productively, especially when things get uncomfortable or heated.

By positioning your ideas well and having productive conversations about them:

- You gain agreement and support for taking the next step forward.

- You save yourself from getting embroiled in conflict: the most dangerous, high-stakes playing field.

Conflict: Fighting About Ideas

Being taken seriously during controversy is important. Thinking seriously about the risks of conflict is essential. When issues escalate into conflict, our jobs and reputations are on the line. We need to ask ourselves whether the issue is important enough to continue the fight. The fallout on both professional and personal levels can take a toll.

It is during conflict that we’ve had friends at work abandon us. People don’t want to be “tainted” by being involved in conflict that may not end well. They don’t want to risk being seen as our supporters and thus by default supporters of an unpopular issue.

Reading the Riot Act

We often become strident during conflict. In fact, the ultimate rebel moment during conflict may come when we decide to read the riot act to the powers that be.

Warning

The rebel riot act is a last resort, a tactic you hope you don’t have to use. Calculate the consequences if it isn’t received as you hope it will be.

Steve was so frustrated with the executive team’s resistance to new ideas that he finally read them the rebel riot act.

He told the executives that despite all their talk about innovation, managers across the company were stifling innovation. Internal entrepreneurs would continue to leave unless the company changed in some very significant ways. Steve laid out a plan for change, based on research, collaboration with his internal rebel alliance, and exactly what he thought the plan could accomplish.

Reading the riot act to established powers gets attention. It is also risky and requires a lot of credibility. Steve succeeded in getting a rebel innovation pilot funded, but he knows that if he doesn’t accomplish his goals in a year, he’ll be asked to leave the company.

A wake-up call

The original Riot Act was an English law, enacted by Parliament in 1715. If more than 12 people “tumultuously” assembled and refused to disperse within an hour of a magistrate reading a proclamation, they would be charged as felons. In the last century, “reading the riot act” has become a common expression. It’s usually a reprimand or warning to get rowdy characters to stop behaving badly. Reading the riot act is a high-intensity intervention for times when no one seems to be listening.

Rebels read the riot act not because people are rowdy, but because they are complacent. There are times we may need to read the riot act to wake people up to the need for change and to explain that management’s refusal to consider alternatives is in fact neglect and is putting the organization at risk.

If an organization has a transparent corporate culture, like Steve’s, you are more likely to be able to read the riot act as a way to try to create positive change. Reading the riot act indicates that you care about your organization. You want to help the organization to change and be a part of the change.

Formulating a rebel riot act

A good rebel riot act describes what’s at stake and offers a high-level plan to get from today’s pain to tomorrow’s outcomes. Unlike the “what’s at stake” communications approach during controversy, the riot act has a harder bite, a forceful tone, an extremely thorough plan, and a specific call to action. It should include:

- A succinct summary of the problem and its risk to the business. No mincing words.

- Data, or at least several credible anecdotes, to support the point. This can’t be viewed as your opinion. You show a pattern that has negative consequences.

- A proposed plan to correct the problem. If you’re going to read the rebel riot act, be prepared to ask for what you think can solve the problem.

- Willingness to lead the change, including what you expect to accomplish by when.

When You’re Mad as Hell

Anger often flares up when we’re in conflict. Rebel frustrations can grow so acute that we lash out when our bosses and colleagues least expect it, surprising everyone, especially ourselves. We feel momentarily victorious about saying what needed to be said. The outburst relieves pent-up stress, but then we realize that we have damaged ourselves. People have paid attention to our anger but have not necessarily gotten the point.

When something sets us off, our hearts start racing, our jaws clench, we sweat, our mouths go dry, and the voice in our head barks at us like a drill sergeant, “Set the record straight right this minute, damn it. Don’t be a wimp. Give it to them.”

In a rage, we attack with our words. We come across as judgmental and hotheaded. When we spew our anger, people run for cover or shut down as they wait for us to finish our rant.

Nothing good comes from these outbursts. Most damaging is that our anger gives others ammunition to discredit us, labeling us as loose cannons, temperamental, hot-headed, immature, unstable, lacking judgment, and maybe even asses. It is all code for implying not so subtly that we are not people the organization can, or should, trust.

What a mess. When you feel you’re about to erupt, call on behaviors that help you cool down before spouting off. This requires enormous discipline and much practice. While we have gotten better at this, there are times we still blow up the bridge instead of building it. Anger is such a weakness for so many of us.

Here are some techniques to practice (and they will take practice) to manage anger. When we can learn from and control our anger we’re able to act with more credibility, calm, and effectiveness.

No personal attacks

We’ve mentioned this before when talking about the BBBs and it bears repeating: never attack people, use hurtful or rude language, or belittle them. Personal attacks cut the deepest and are the hardest to recover from. Go after issues, not people.

Look at their side

Try to understand what it’s like to be the person (or group) you’re angry with. What are they trying to protect? What makes them uncomfortable? What are they afraid of? How people talk about something conveys more information than the words themselves. Listen for the emotion beneath the words. This empathy will help neutralize your anger and help you see more clearly.

Find out what your anger is telling you

Consider the source of your anger a new piece of data to examine. There’s something to be understood in why you are angry. Try to observe the real issues. This calms down the negative anger and prevents you from lashing out. You’ll glean valuable insights by taking this approach, and you’ll earn credibility by showing people that they can express ideas without anyone dismissing them or biting their heads off.

It’s not about being right

When we’re angry, we often believe we’re right and they’re wrong. This belief shuts down dialogue. Everyone’s views are valid. (Unless some excellent research proves otherwise. If that’s the case, show them the data and get onto objective territory as fast as you can.) “Your views are valid. It is risky to change a process that’s been in place for years. Similarly, my views are valid too. We face other types of risks if we don’t change this process.” If you acknowledge others’ views, they are more likely to appreciate yours. This sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t, especially with BBBs. It’s still an approach worth trying.

Acknowledge the tension and disagreement

Disarm the situation by acknowledging that tensions are high and disagreements are real. Here are some tactics:

- We’re all feeling frustrated and on edge. Let’s go around the room and share what we’re feeling in a sentence or a couple of words.

- We’re not making progress because emotions are running high. Should we adjourn and cool off?

- Are there data points that might help us see more clearly?

- Should we get someone outside our group to facilitate so that we can resolve this?

These questions recognize the tension and offer an active approach to finding ways to address them. Often people suppress their anger, appearing passive while inside the frustration continues to build, increasing the chances of a harmful emotional outburst when you least expect it.

Quarantine your email and your mouth

Impose a 24-hour no-email, no furious phone call quarantine on yourself. Take a walk or get out of the office. If you’re pressed by the other person to respond, say, “I have to reflect on this before being able to respond in a helpful way.”

Make a list

Don’t think; write. Writing while angry cools you down while capturing potentially valuable ideas. Consider these prompts:

- What are the 10 things that worry people most about this idea?

- What 10 pieces of objective data or anecdotal evidence could help people open up their thinking about this?

- What are 10 things I can do to move the idea ahead that don’t require approval or meetings with people who oppose the idea?

- Which 10 people could I talk to who could help me see a way to move ahead?

- What are the 10 worst things that will happen if I abandon this idea?

Anger will always be there

Lastly, accept that anger will always be present and powerful for us. Sometimes we don’t realize how much we’re invested and are unprepared for the anger that surges within us when things go wrong. We care too much about too much. The secret is being aware of the paradox of anger. It can give power and it can derail it. Use the power, and find ways to stop yourself from doing and saying things that derail your credibility.

As we’ve said, rebels tend to see possibilities and move ahead faster than most people at work. Helping others see new ways always takes longer than we think it should, and more people, processes, and task forces will try to block us along the way than we ever could envision. Persistence and purposeful patience helps; lashing out and biting their heads off doesn’t.

Questions to Ponder

- If you were better at having difficult conversations, what would be different for you at work? What might you be able to accomplish?

- What would help you better deal with controversy and conflict? What two or three practices might be most valuable?

- How might you improve how you guide conversations during controversial meetings so that you achieve your meeting goal? What questions are most useful when you’re discussing controversial issues?

- The risks are formidable when you get into the conflict stage. Is your idea worth what’s at risk to you? How do you know?

- Have you anticipated the tough questions?

- What helps you control your anger?

[5] We say “try” because it may not be within your power to keep drama down during a meeting. Read the section on conflict later in this chapter even if all you anticipate is controversy.