Chapter 4. Qualitative Research

Many businesspeople, even those responsible for the online experience, don’t spend nearly enough time trying to see their business through the eyes of the customer. Qualitative research offers an invaluable way not only to get into the customer mind-set, but also to come up with ideas for innovation. This chapter discusses several types of qualitative research and shows how they can be used to generate test ideas while providing insights that will help guide the business in an evolving marketplace.

Benefits of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is the art of capturing the customer’s perspective on the online experience offered by a business and its competitors. Companies often neglect to do qualitative research and instead take the easy route by relying solely on analytics software to understand their customers’ online behavior. However, quantitative research can only reveal how site users are acting; it can shed very little light on what they are thinking or feeling. In short, it is no substitute for truly seeing a company through the eyes of its users. This is not always a comfortable experience for business leaders, but it is key to helping them understand the customer perspective, adapt their business to evolving conditions, and generate ideas for new designs—tasks that metrics alone cannot fulfill.

In particular, qualitative research is critical to identifying:

![]() Unmet customer needs. If a business is failing to provide customers with what they’re looking for, no analytics report can shed light on that gap. By watching and listening to customers, or by re-creating their online experience firsthand, researchers can discover users’ expectations, unmet needs, and any sources of frustration.

Unmet customer needs. If a business is failing to provide customers with what they’re looking for, no analytics report can shed light on that gap. By watching and listening to customers, or by re-creating their online experience firsthand, researchers can discover users’ expectations, unmet needs, and any sources of frustration.

![]() The why behind the analytics data. Sometimes metrics can generate more questions than answers. For example, an analytics report showing an increase in page views per visitor isn’t always a good sign. Although it may indicate customers’ satisfaction through deep engagement with the site, it may also indicate confusion about how to add products to their cart, or reveal unsuccessful attempts to locate information such as shipping rates or to find pages on the site that customers think should exist but do not.

The why behind the analytics data. Sometimes metrics can generate more questions than answers. For example, an analytics report showing an increase in page views per visitor isn’t always a good sign. Although it may indicate customers’ satisfaction through deep engagement with the site, it may also indicate confusion about how to add products to their cart, or reveal unsuccessful attempts to locate information such as shipping rates or to find pages on the site that customers think should exist but do not.

Most qualitative research methods work with small, even statistically insignificant, sample sizes. As a result, this kind of research is best used for understanding broad questions—such as whether customers understand the basic business offering and whether it’s something they need—as opposed to informing decisions about how to design every detail of a business. For the same reason, researchers often verify hypotheses based on qualitative data by referencing web analytics or testing to see if the hypotheses apply to a large number of customers.

Learning More About Customer Goals

The first step in qualitative research is to define realistic customer goals that explain why customers are choosing to interact with a business. This is not as easy as it sounds: Customers may access a site for very different reasons, and their goals can and do change over time. As Rob Blakeley, Senior Product Manager for WebMD, put it, “Our customers’ goals are as different as there are blades of grass in New York City’s Central Park.”

However, most businesses can easily identify a preliminary list of the most likely customer goals and adapt this list as researchers gather further information. For example, a financial services company’s customer goals may include opening or closing a deposit account, sending and depositing checks from a mobile device, getting a replacement credit card while traveling abroad, and so on.

If a businessperson is struggling with this task, it may help to ask the question: If customers could come to the business looking for help with only one thing, what would it be? It’s much better to create a top-notch experience that can satisfy one important goal shared by many customers than to create several mediocre experiences in an attempt to address many different objectives.

Starting to Answer Qualitative Questions

The next step in qualitative research is to build a list of questions to explore. Like the customer goals, this list is preliminary and will change over time. The following is a list of potential questions that companies may use as a starting point in this process; of course, each business will tailor the list to its own priorities.

Fundamental questions:

![]() Why do customers come to the business?

Why do customers come to the business?

![]() Why do they leave?

Why do they leave?

![]() Do customers understand what the business has to offer?

Do customers understand what the business has to offer?

![]() Do customers want what the business has to offer?

Do customers want what the business has to offer?

![]() Is there anything customers want from the business that it is not providing?

Is there anything customers want from the business that it is not providing?

![]() When analytics data shows areas of concern—for example, high drop-off rates, repeat page views, and so on—what are the reasons for the customers’ actions?

When analytics data shows areas of concern—for example, high drop-off rates, repeat page views, and so on—what are the reasons for the customers’ actions?

![]() Which product or service is most important to customers?

Which product or service is most important to customers?

![]() If the business could focus on only one product or service, what should it be?

If the business could focus on only one product or service, what should it be?

On finding products, services, and content:

![]() Is the full breadth and depth of the product/services/content offering apparent?

Is the full breadth and depth of the product/services/content offering apparent?

![]() Are there too many or too few products/services/content to choose from?

Are there too many or too few products/services/content to choose from?

![]() Do customers easily find products/services/content using site navigation and/or search?

Do customers easily find products/services/content using site navigation and/or search?

On the customer’s decision-making process:

![]() Are products/services/content easy to differentiate from one another, or are they too similar, leading to customer confusion over which to choose?

Are products/services/content easy to differentiate from one another, or are they too similar, leading to customer confusion over which to choose?

![]() Are the cross-sells, up-sells, and promotions clear? Do they interfere with the primary purchase?

Are the cross-sells, up-sells, and promotions clear? Do they interfere with the primary purchase?

![]() Is there enough information to make a purchase decision?

Is there enough information to make a purchase decision?

![]() Is it clear how to find related or popular content? Does it interfere with the primary content experience?

Is it clear how to find related or popular content? Does it interfere with the primary content experience?

On conversion:

![]() Are there barriers to easily checking out?

Are there barriers to easily checking out?

![]() Are prices, taxes, shipping, returns, and security protections apparent? Are any of them barriers to checking out?

Are prices, taxes, shipping, returns, and security protections apparent? Are any of them barriers to checking out?

![]() Are there barriers to easily viewing additional content?

Are there barriers to easily viewing additional content?

On the competition:

![]() Which competitors do customers go to, and how do the preceding questions apply to these competitors?

Which competitors do customers go to, and how do the preceding questions apply to these competitors?

![]() Do competitors offer a product or service that would complement the business’s offerings, such as accessories for a product the business sells? If so, should the business offer it as well?

Do competitors offer a product or service that would complement the business’s offerings, such as accessories for a product the business sells? If so, should the business offer it as well?

Note that some of the preceding questions are based on quantitative research; however, it is not essential to have performed quantitative studies before tackling qualitative research. Most businesses already have a basic understanding of their data, and the iterative method means new insights, from both kinds of studies, will be added to the mix throughout the process, allowing team members to refine and add to their list of questions.

The next step in qualitative research is to try to answer these questions through firsthand experience, observing customers, and other methods, as described in the following sections.

User Experience Reviews

In user experience reviews, or heuristic reviews, researchers strive to experience the business firsthand in the same way customers do; then they do the same on competitors’ websites for comparison. Before we examine user experience reviews in detail, it is helpful to explore some guidelines on customer behavior that can help the researcher, or reviewer, make their customer experience as authentic as possible.

Online Customer Behavior

Customers generally display the following tendencies when interacting with an online business:

![]() Customers are goal-oriented. They’re looking for a place to click on the page or app that will take them to the specific product, service, or content that constitutes their objective.

Customers are goal-oriented. They’re looking for a place to click on the page or app that will take them to the specific product, service, or content that constitutes their objective.

![]() Customers scan pages quickly. They skip over details until they’ve found what they’re looking for. For example, they may click through a business’s homepage and several category and product pages rapidly, navigating with the help of images or keywords until they find a product they’re interested in; only then are they likely to read details such as the price, feature list, reviews, and shipping policy. They are very good at ignoring anything that looks like advertising, a tendency that is sometimes called banner blindness.

Customers scan pages quickly. They skip over details until they’ve found what they’re looking for. For example, they may click through a business’s homepage and several category and product pages rapidly, navigating with the help of images or keywords until they find a product they’re interested in; only then are they likely to read details such as the price, feature list, reviews, and shipping policy. They are very good at ignoring anything that looks like advertising, a tendency that is sometimes called banner blindness.

![]() Customers don’t act like professionals. They don’t think about whether the navigation is consistent, which page they’re on within the site, how individual page elements are working, what the business is trying to get them to do next, and so forth.

Customers don’t act like professionals. They don’t think about whether the navigation is consistent, which page they’re on within the site, how individual page elements are working, what the business is trying to get them to do next, and so forth.

Experiential Business Review

Researchers first choose a realistic customer goal from the prepared list, and then follow a “customer scenario”—the actions a customer would take to pursue that objective. It is important here to step out of the professional mind-set and just experience the website as a customer would: If the reviewer can relate personally to the goal, all the better. For example, for a retail business the reviewers could go through the “browse and purchase” process for an item they’re interested in buying or would like to get as a birthday gift for a friend; for a travel business, the reviewers could look into booking their next trip.

Taking notes along the way, reviewers should strive to do anything customers would do—call customer support, abandon the site when unable to attain their goal easily, and so on. If many customers visit the site from mobile devices, reviewers should try going through the scenarios using a phone or tablet.

After experiencing one scenario, the reviewers retrace each step of the experience to critique it as a professional, noting any opportunities for improvement. Was it easy to accomplish the goal? Were some elements especially difficult to navigate? Were there steps that confused the reviewers? The reviewers then repeat this process for the remaining customer goals.

Experiential Competitive Review

Because customers are also visiting competitors’ websites, reviewers should do so, too. They follow the same procedure as before, exploring the same scenarios as customers, and then return to each step to critique the experience as professionals. To make the experience especially organic, reviewers may even start on their own business’s site and then abandon it for a competing site based on their natural browsing behavior or on analytics data that shows where customers tend to abandon.

Documenting Experiential Reviews

It’s important to document the heuristic reviews to share the findings and to prepare for the observation of real customer interactions. The documentation process should consist of screen shots showing the step-by-step interaction path, notes explaining the screen shots, and an updated list of qualitative questions based on the review. For example, researchers may ask whether customers also struggle or get confused where the reviewers did or whether users find it easy to navigate the same paths as the reviewers.

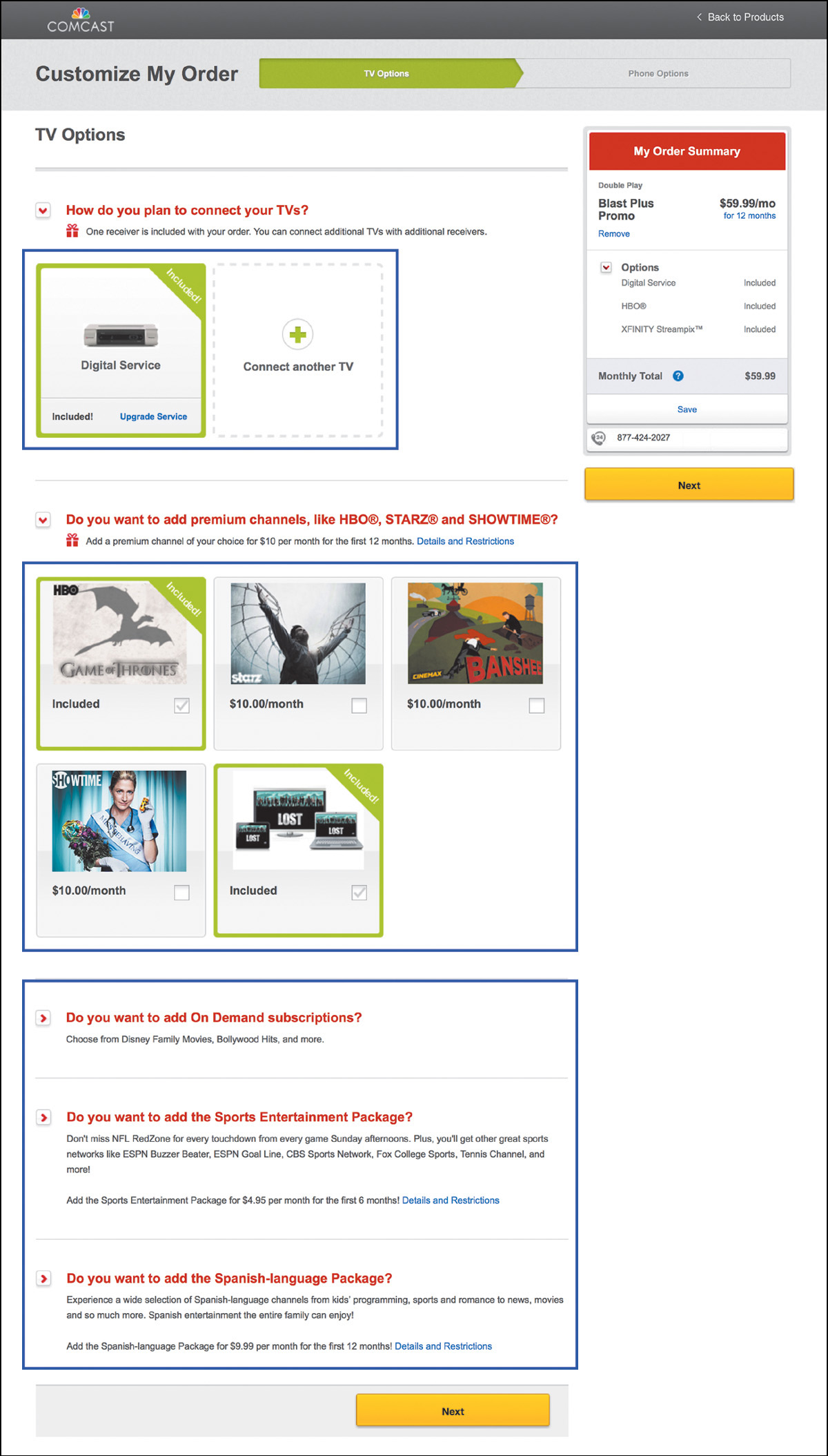

The following example illustrates how this process typically unfolds through a user experience review of the Gap, Inc. conducted in 2013. Figure 4.1 encapsulates the main steps of the experiential review.

Figure 4.1 It’s easy for customers to get confused or frustrated online. In this example of a user experience review, the customer would have abandoned the site after struggling to purchase the red dress she liked on the homepage.

The accompanying notes for the steps in the figure include:

1. Reviewer visits Gap.com to look for a summer dress.

2. Reviewer sees red dress in middle right that looks cute and clicks on it. Reviewer is not taken to the dress but to a page listing many dresses that don’t look like the one she clicked.

3. Reviewer sees a similar dress in a different color on the second row and clicks on it. Reviewer decides to purchase it. She tries to change the color to red by clicking on the large image of the dress in the middle of the screen, but doing so simply shows a zoomed-in view of the dress.

4. Just before abandoning, reviewer clicks on the small image of the dress in the middle of the screen.

5. Reviewer now sees the color palette and realizes that the dress is no longer available in red. She decides to buy it in coral as pictured. She clicks on “add to bag” but nothing happens, so she leaves to shop at a competitor’s site. (The “add to bag” link failed because she first needed to select a size; there was no error message explaining this.)

Upon further critiquing the experience, the following questions were generated for the observational stage of the research:

![]() Do customers also struggle to find the product page for an item they liked on the homepage?

Do customers also struggle to find the product page for an item they liked on the homepage?

![]() Even though it was jarring to be taken to a page with hundreds of dresses after clicking on a single one, would it be a good customer experience to arrive on a page like that after clicking on the “Dresses” category in the Women’s section of the site?

Even though it was jarring to be taken to a page with hundreds of dresses after clicking on a single one, would it be a good customer experience to arrive on a page like that after clicking on the “Dresses” category in the Women’s section of the site?

![]() Do customers also struggle to figure out what colors an item comes in and how to choose a different color?

Do customers also struggle to figure out what colors an item comes in and how to choose a different color?

![]() Do customers also find it difficult to add an item to their cart?

Do customers also find it difficult to add an item to their cart?

![]() Do customers also try to buy before selecting a size and get confused when no message reminds them to pick a size or offers to help them do so?

Do customers also try to buy before selecting a size and get confused when no message reminds them to pick a size or offers to help them do so?

Researchers seek to validate these questions by observing customers interacting with the site and by digging into the site analytics. Team members then create hypotheses, or proposed answers to these questions, and attempt to vet the hypotheses through test ideas, which are added to the Optimization Roadmap.

Don’t Act Too Quickly

The purpose of the user experience review is to gain insights into the customers’ experiences by stepping into their shoes for a moment. However, team members should resist making immediate changes to the site based solely on heuristic reviews unless clear technical errors are uncovered. Otherwise, the changes may reflect the perspective of online professionals, not the typical customer.

Conducting realistic user experience reviews is a skill that can be learned over time, but improvement requires an adequate feedback loop: Reviewers need to watch actual customers interact with the business and test new designs, not simply criticize the company’s site in a vacuum.

Researchers must also exercise caution when exploring competitors’ sites. All too often businesses assume a competitor’s designs are effective and simply copy them without finding out whether these designs would work for their own business. As a result, not only do they risk adopting ineffective designs, but their sites also wind up looking very similar to those of their competitors.

One way to avoid this pitfall is to review sites outside of the business’s circle of competitors when looking for new ideas; no matter where they find new concepts, companies must test them before pushing them live to all customers.

Observational Customer Research

Directly experiencing a site can be a great way to generate questions that lead to test ideas, but it’s no substitute for spending time with real customers. As noted in Chapter 1, users aren’t very good at articulating exactly what they need, so rather than asking customers for their opinions, observational research instead pays close attention to their behavior as a way of understanding their perspective. Team members strive to watch customers interacting naturally with the site; they provide them with opportunities to give open-ended feedback and avoid guiding them too much or prompting them with leading questions.

Customers are recruited in a variety of ways; although some volunteer, they’re more often compensated through some form of payment, such as a check or gift card. Even though customers know they’re being observed, the goal of this type of study is to create as natural a setting as possible, so it may take place not only in research facilities, but also in cafés, customer homes, and other venues. Sessions are conducted one-on-one, with additional researchers observing behind one-way glass or through a video feed.

Depending on the business, sessions can last anywhere from 10 to 60 minutes. High-level trends usually start to emerge after watching four or five customers, but to be on the safe side, researchers often observe eight to ten customers during each study. The frequency of observational studies varies according to the company, but most businesses should conduct them at least quarterly. Many sizable and successful companies conduct this type of research whenever they have pressing unanswered questions about their business, which could arise several times per month.

The following list outlines the basic framework for this type of research, as well as some best practices for observing customers online:

Recruitment

![]() The first few times a business conducts this type of research, it may be helpful to go through a recruitment agency and use an expert moderator to conduct the sessions. Later, the business can recruit by placing an ad online on a site like Craigslist or work with existing customers contacted through an internal email list.

The first few times a business conducts this type of research, it may be helpful to go through a recruitment agency and use an expert moderator to conduct the sessions. Later, the business can recruit by placing an ad online on a site like Craigslist or work with existing customers contacted through an internal email list.

![]() It is useful to recruit customers based on an experience they recently had or an upcoming experience that the business can help with. For example, a hospitality business might recruit customers who have recently booked a hotel room online or who need to book a room for an upcoming trip.

It is useful to recruit customers based on an experience they recently had or an upcoming experience that the business can help with. For example, a hospitality business might recruit customers who have recently booked a hotel room online or who need to book a room for an upcoming trip.

![]() If possible, the customers should not know the name of the business, because this information might influence their behavior. For example, recruiters can tell them the study is about online user behavior related to the general category of tasks the business is interested in observing (purchasing clothing, reading the news, searching for general information, and so on).

If possible, the customers should not know the name of the business, because this information might influence their behavior. For example, recruiters can tell them the study is about online user behavior related to the general category of tasks the business is interested in observing (purchasing clothing, reading the news, searching for general information, and so on).

Setting scenarios

![]() When customers arrive, the researcher welcomes them and asks questions that prompt them to talk about a wide range of recent online experiences, such as “What have you recently shopped for online?” or “Have you planned any trips recently?”

When customers arrive, the researcher welcomes them and asks questions that prompt them to talk about a wide range of recent online experiences, such as “What have you recently shopped for online?” or “Have you planned any trips recently?”

![]() The researcher provides customers with a computer or mobile device that allows them to browse the web while recording their online session and facial expressions. (Of course, customers are informed in advance that their session will be recorded.)

The researcher provides customers with a computer or mobile device that allows them to browse the web while recording their online session and facial expressions. (Of course, customers are informed in advance that their session will be recorded.)

![]() The researcher invites the customers to go through a scenario they had mentioned earlier that pertains to the business (e.g., booking a hotel room for an upcoming stay). Customers are asked to speak aloud while using the computer to let the researcher know what they’re thinking.

The researcher invites the customers to go through a scenario they had mentioned earlier that pertains to the business (e.g., booking a hotel room for an upcoming stay). Customers are asked to speak aloud while using the computer to let the researcher know what they’re thinking.

Observations

![]() The researcher then sits back, pays close attention, and tries not to say anything. The key is to leave customers alone while carefully watching how they try to reach their goal—and what obstacles they face along the way—and paying close attention to shifts in body language, facial expressions, and so on.

The researcher then sits back, pays close attention, and tries not to say anything. The key is to leave customers alone while carefully watching how they try to reach their goal—and what obstacles they face along the way—and paying close attention to shifts in body language, facial expressions, and so on.

![]() The researcher refrains from asking customers what they think about specific websites or designs. For example, the researcher does not ask whether certain sites are easy or helpful. Instead, the researcher focuses on what customers show through their actions; the more customers are prompted, the more likely they’ll be to say or do something based on what they think the researcher wants to hear. If customers get confused and ask what to do, the researcher simply says something like, “Please do whatever you would normally do.”

The researcher refrains from asking customers what they think about specific websites or designs. For example, the researcher does not ask whether certain sites are easy or helpful. Instead, the researcher focuses on what customers show through their actions; the more customers are prompted, the more likely they’ll be to say or do something based on what they think the researcher wants to hear. If customers get confused and ask what to do, the researcher simply says something like, “Please do whatever you would normally do.”

On prompting the customer

![]() Some customers have a tendency to remain silent throughout the session. If this is the case, the researcher will occasionally prompt them with a kind reminder to vocalize their thoughts.

Some customers have a tendency to remain silent throughout the session. If this is the case, the researcher will occasionally prompt them with a kind reminder to vocalize their thoughts.

![]() If, toward the end of the session, customers haven’t used the online business, the researcher may prompt them by saying something like, “I’m interested in seeing you do the same thing with a few specific websites.” The researcher will give the customers a list of sites that includes the business being studied as well as competitors not yet visited.

If, toward the end of the session, customers haven’t used the online business, the researcher may prompt them by saying something like, “I’m interested in seeing you do the same thing with a few specific websites.” The researcher will give the customers a list of sites that includes the business being studied as well as competitors not yet visited.

![]() The researcher should wait until the end of the session to ask any specific questions about the customer’s behavior, and even then, they should avoid asking for any opinions. For example, a researcher can ask customers to explain what they were thinking at a specific moment rather than asking if they thought the experience was good or not. When listening to their answers, the researcher should be on the lookout for a mismatch between what customers say and their observed actions. People tend to jump around online from website to website very quickly and usually have difficulty remembering all the actions they took online, let alone why they took them.

The researcher should wait until the end of the session to ask any specific questions about the customer’s behavior, and even then, they should avoid asking for any opinions. For example, a researcher can ask customers to explain what they were thinking at a specific moment rather than asking if they thought the experience was good or not. When listening to their answers, the researcher should be on the lookout for a mismatch between what customers say and their observed actions. People tend to jump around online from website to website very quickly and usually have difficulty remembering all the actions they took online, let alone why they took them.

![]() At the end of the session, the researcher should thank the customers for their time and pay them the agreed-upon fee.

At the end of the session, the researcher should thank the customers for their time and pay them the agreed-upon fee.

After the session, the researcher reviews the video to capture any findings that provide insights into the list of qualitative research questions. These insights, in turn, may lead to the formulation of new questions for further exploration in the iterative process.

Other Research Methods

Although heuristic reviews and observational customer research are the most common methods, there are many other types of qualitative customer research. This section outlines some that are popular among online businesses.

It should be noted that two methods that remain popular today—focus groups and usability testing—do not figure in this section because they are not recommended. Focus groups tend to place customers in the role of product designer by explicitly asking them to give advice on design decisions, which is difficult for people to do when such decisions are not their area of expertise. Additionally, focus group participants tend to try to say the “right thing” to please the researcher or they succumb to groupthink.

Traditional usability testing asks customers to complete a predetermined list of online tasks based on actions the business would like to see completed rather than allowing customers to show the business their natural online behavior. Even though customers may be good at figuring out how to perform a task when asked, doing so takes them out of their typical frame of mind when interacting with websites.

Instead, the following are several tried-and-true methods for understanding customers through qualitative research.

Ethnographic Studies

Ethnographic studies are a special form of observational research that take place where the customer would normally interact with the company, such as at their home or office, or at the location of the business itself, so that they are more likely to behave the way they normally would. Just like observational customer research, these sessions are most effective when they are unguided and researchers focus on active watching and listening.

Kenyon Rogers, Director of Digital Experiments for Marriott International, said that his business regularly conducts ethnographic studies at select hotel properties. For example, in 2013 the company piloted a program that allows guests to “use their smartphones to check into the property and open their room door without needing to interact with a Marriott team member.” Rogers added that very soon, “guests will be able to control their entire experience, including ordering room service, extending their stay, ordering transportation, and booking meeting rooms through their smartphones.”

Surveys

Businesses place surveys on their actual site or app, or email them to customers. Large surveys can have statistically significant sample sizes, but the researcher must be on the lookout for data not representative of the larger customer base due to self-selection bias. For example, not every customer wants to fill out a survey, and those who do may have the strongest positive or negative opinions.

As with all forms of qualitative research, the more open-ended the survey, the better. Surveys that ask customers about specific design decisions place the customer in the awkward position of being asked to provide advice outside of their area of expertise. Rather, understanding whether customers found their overall experience to be positive or negative and providing an open-form field for customers to write about any aspect of the experience they choose can often lead to actionable data.

Customer Panels

Customer panels are a subset of surveys: They typically consist of thousands of participants who have elected to give survey feedback on a regular basis. Panels may be run by a company’s research team or by consulting firms on behalf of many businesses. Like surveys, customer panels can provide statistically significant sample sizes, but it’s important to understand the segment of participants being queried. For example, although panels consisting entirely of self-selected users of one business might not be representative of the entire population, they can give the business insight into the behavior and opinions of their more loyal customers.

Eileen Krill, research manager at The Washington Post, oversees customer research for all of the business’s print and digital brands. A panel of about 7,000 customers is included in the many types of qualitative and quantitative customer research she oversees. Krill will ask the panel “a wide range of closed and open-ended questions, depending on the objectives of the survey,” including “satisfaction rating questions.” She points out that “open-ended feedback is generally far more meaningful and actionable than the score itself” because it can help to “reveal the reasons behind the scores.”

One question she often asks the panel is “whether a new product or feature will improve the customer’s impression of The Washington Post brand.” Although in most cases participants say such additions would have no impact, Krill still asks the question in case it provides an important insight. For example, she said, “We once tested the idea of starting an online dating service for Post readers, and that got a lot of people saying they would have a lower opinion of the company.” Krill noted that “I think that research was one of the key things that may have killed the idea.”

Diary Studies

Diary studies consist of a business asking customers to take notes and regularly send them back to the company, usually over an extended period of time. These studies may ask participants to take notes only on a specific topic area, like their regular interactions with a new site or app, or they may be more general and simply ask customers how they spent their day.

Google Search Lead Designer Jon Wiley shared an example of an ongoing diary study being run by the company. Through a mobile app, the study regularly asks participants to reply to the question: “What is the last bit of information you needed to know?” The information can be related to any aspect of their life, not only the material they were looking for online. Wiley and his team then “look at the needs that people have in their lives” and try to answer the question, “Is there a way that we, as Google, can find a solution for them?”

Card-sorting

A technique used to gain insight into how to organize content, such as ordering and grouping similar navigational links, card-sorting directly involves customers in the design process. Customers are provided with a stack of cards containing information and asked to perform a task, such as organizing them into logical categories. Although it is typically performed with index cards or sticky notes, card-sorting can also be performed online, and there is no limit to the number of participants.

Caution should be observed, because this technique is more guided than the aforementioned qualitative methods and may place customers in the position of being asked to act like a professional designer. However, if performed with minimal prompting, card-sorting can provide designers with a rare opportunity to gain insight into how customers think about information architecture and content hierarchies.

Nate Bolt, design research manager at Facebook, said the company used cart-sorting as one of many qualitative research methods to inform an ongoing redesign of users’ Facebook News Feeds. After recruiting users, the Facebook Design Research team printed out each user’s feed, up to the minute, on paper. Then, he explained, “they would cut out their feed stories, place them on a table, and group them into what they considered to be like-minded categories. That helped us reprioritize the ways that stories are grouped and organized within people’s News Feeds in a real, human way. Obviously, this went hand in hand with all other data, including the system (analytics) data.”

Feedback Forms

Feedback forms on websites, or email addresses for user feedback, can be a good source of information. Users who provide open-ended feedback in this way often have timely insights into customer frustrations, as well as positive comments on great experiences with the website or the business’s team members.

John Williamson, the Senior Vice President and General Manager of Comcast.com, explained that “One of the best sources for information I have is the ‘Website Feedback’ link” that appears on the bottom of each page on the site. Williamson noted, “I was in banking in the mid-1990s, and I remember how excited we would get if we received a letter from a customer. We really would.” Every day Comcast receives “hundreds of letters” from customers through the feedback link, and because they are a “huge benefit” that helps Williamson and his team understand their customers and their business, he added, “I read every one of them.”

Acting on Qualitative Research

After the heuristic and other qualitative research sessions have been conducted, researchers summarize the insights they have garnered, as well as any remaining questions about customer behavior. For each insight, they write down possible ways of verifying the observations through analytics data, as well as any ideas for testing. This list will be used as a guide when crafting the Optimization Roadmap.

Case Study: Comcast

A leading provider of television, high-speed Internet, and digital voice services in the United States, Comcast uses qualitative and quantitative research to inform the iterative design process it applies to all aspects of its site.

Qualitative studies play a critical role in Comcast’s design process. Williamson noted that in one redesign process during 2012, “We had over a thousand customers and prospective customers involved before we tested online....We had ethnographic research, customer panels, and online customer panels.” The Comcast team also “went into the homes of over 20 customers and saw how they interacted with Comcast,” which provided “critical” experiences that analytics “data cannot replace.”

The following business case shows how insights gathered from qualitative studies triggered a redesign of the company’s “TV Options” page, which customers use when purchasing television service online. This section walks the reader through the redesign process from beginning to end, showing how the qualitative study findings led to the formulation of hypotheses and redesign options, and finally to the first tests and the selection of highly effective new designs.

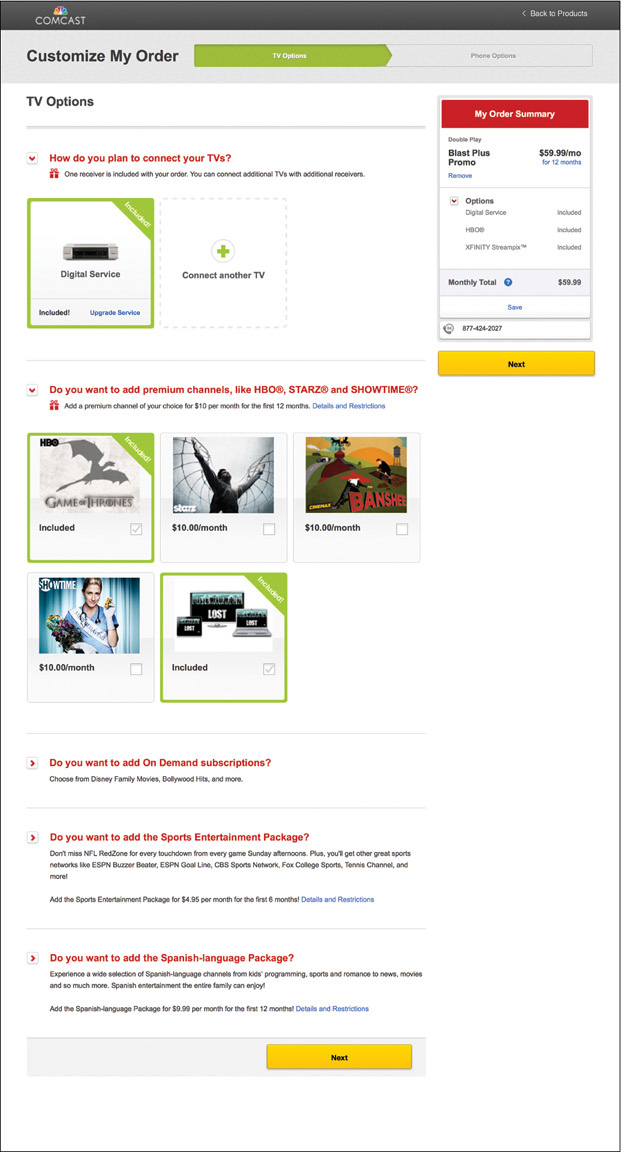

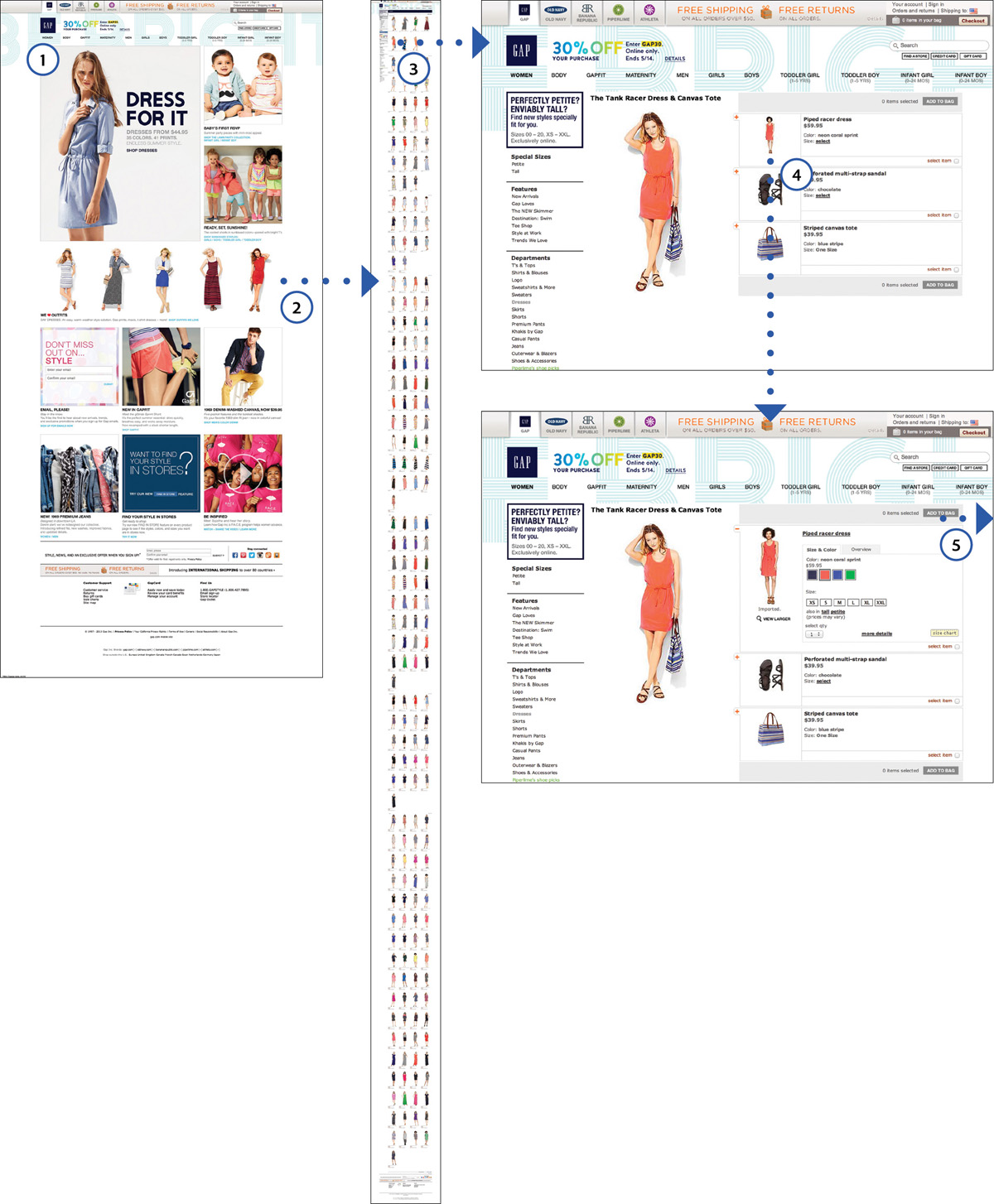

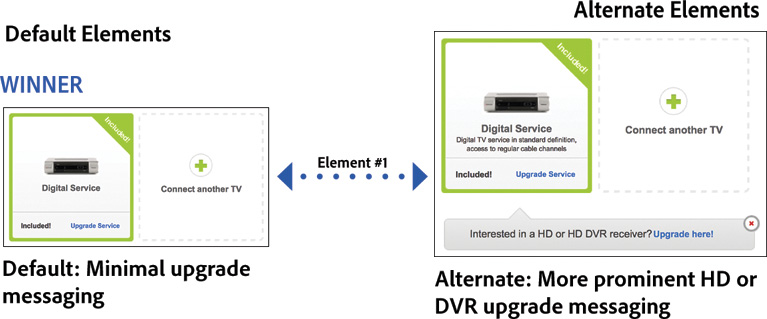

The goal of the “TV Options” page is to help customers choose their receiver type and to select service upgrades, such as premium channels. However, qualitative studies suggested three page elements were underperforming: receiver selection, premium channel logos, and other add-on options further down on the page. The default version of the page, with these three elements highlighted, appears in Figure 4.2.

The qualitative study findings related to these three elements and the steps researchers took in response are summarized here.

Finding. Not all customers interacted with the first step of the process to learn more about upgrading to an HD or HD DVR receiver.

![]() Hypothesis. Customers do not notice the option to upgrade a receiver.

Hypothesis. Customers do not notice the option to upgrade a receiver.

![]() Validate with analytics. Does the link to upgrade the receiver get very few clicks?

Validate with analytics. Does the link to upgrade the receiver get very few clicks?

![]() Test idea. Find out whether more customers would upgrade if more information about the options to switch to an HD or HD DVR receiver appeared on the page without requiring additional clicks.

Test idea. Find out whether more customers would upgrade if more information about the options to switch to an HD or HD DVR receiver appeared on the page without requiring additional clicks.

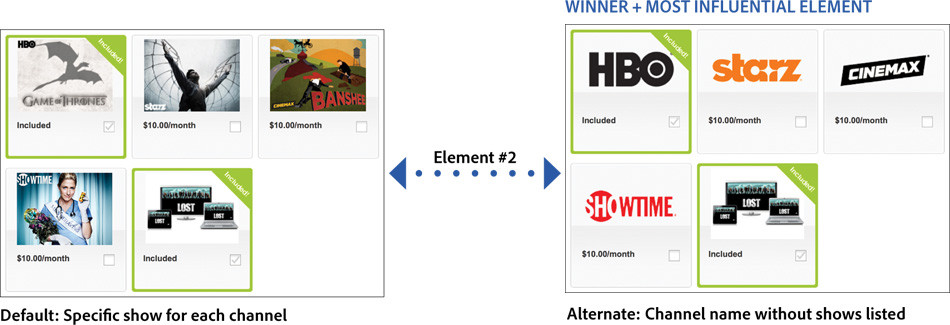

Finding. All customers understood how to select and deselect premium channels, so this function seems user friendly. However, the website highlighted specific shows carried on these channels rather than the actual channels, and several customers commented that they hadn’t heard of these shows. Example: “I never heard of Boss. I never saw Contagion.”

![]() Hypothesis. Highlighting channel names rather than specific shows will clarify the process of adding premium channels.

Hypothesis. Highlighting channel names rather than specific shows will clarify the process of adding premium channels.

![]() Validate with analytics. Do premium channel selections vary based on the featured shows?

Validate with analytics. Do premium channel selections vary based on the featured shows?

![]() Test idea. To appeal to a wider audience, feature prominent channel names (HBO, Showtime, etc.) rather than specific shows.

Test idea. To appeal to a wider audience, feature prominent channel names (HBO, Showtime, etc.) rather than specific shows.

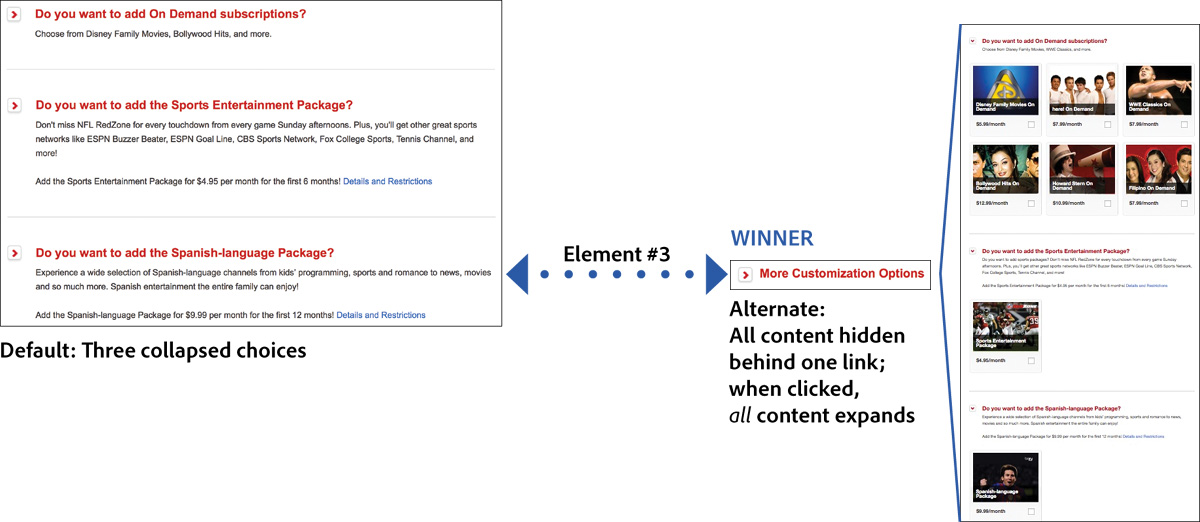

Finding. Several customers commented that they didn’t know what was included in the add-ons. Example: “What exactly is included in the Sports Package?”

![]() Hypothesis. Customers don’t realize they can click on the toggle switches for more information. Because the switches are arranged in rows, followed by messaging for each add-on, customers may be mistaking them for bullet points.

Hypothesis. Customers don’t realize they can click on the toggle switches for more information. Because the switches are arranged in rows, followed by messaging for each add-on, customers may be mistaking them for bullet points.

![]() Validate with analytics. Do customers rarely click on these toggle switches?

Validate with analytics. Do customers rarely click on these toggle switches?

![]() Test Idea. Replace individual offers with a one-line message reading “More customization options” to help customers understand that the image to the left is a toggle switch that, when clicked, will reveal the details of the offers.

Test Idea. Replace individual offers with a one-line message reading “More customization options” to help customers understand that the image to the left is a toggle switch that, when clicked, will reveal the details of the offers.

As noted earlier, researchers targeted receiver selection, premium channel logos, and add-on content for design testing. An alternate version of each element was built and placed in a multivariable test (MVT). A multivariable, or multivariate, test is a special type of A/B test in which several page elements are tested across multiple recipes. Rather than simply testing two versions of the page—one with the original elements and one with the new ones—multiple versions of the page are tested, each including a different combination of the elements. In addition to determining which version of the page has the highest performance, this type of test measures the success of each element.

The default and alternate versions of each element are shown in Figure 4.3. This figure also includes which version of each element won and which out of all three elements most influenced the performance of the page:

![]() Receiver section. The default version has a blue link to upgrade. The alternate version adds a prominent message to upgrade to an HD or HD DVR receiver.

Receiver section. The default version has a blue link to upgrade. The alternate version adds a prominent message to upgrade to an HD or HD DVR receiver.

![]() Premium channel logos. The default version features a specific show for each premium channel. The alternate version features channel logos instead of shows.

Premium channel logos. The default version features a specific show for each premium channel. The alternate version features channel logos instead of shows.

![]() Other add-ons. The default version places content behind four toggle switches. The alternate version places content behind a single toggle switch, which, when clicked, expands to show all up-sell content at once.

Other add-ons. The default version places content behind four toggle switches. The alternate version places content behind a single toggle switch, which, when clicked, expands to show all up-sell content at once.

Figure 4.3 The default and alternate versions of each of the three elements tested. This figure includes the winning version of each element, as well as the most influential of the three winning elements in terms of overall impact on the page.

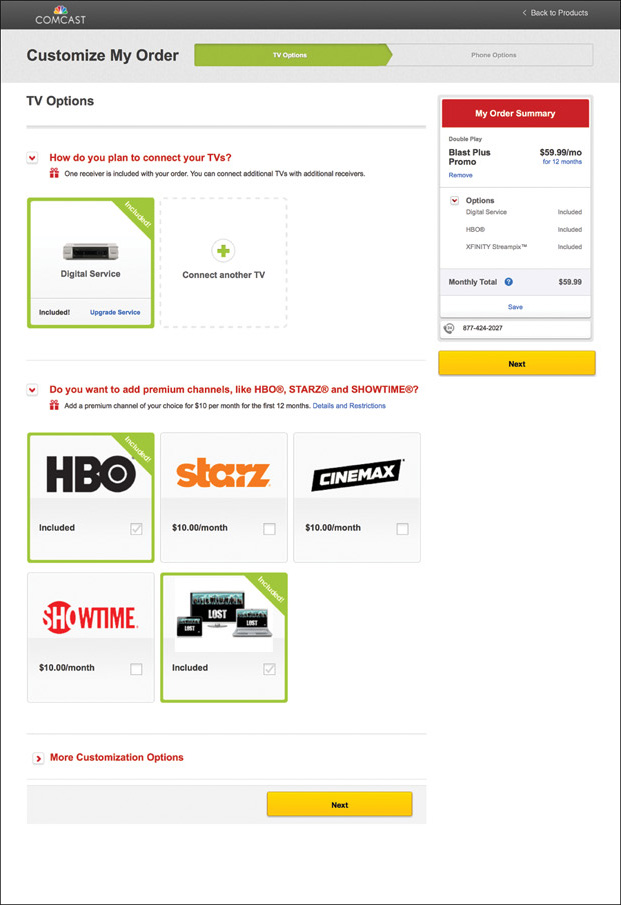

The business goal was to increase the purchase conversion rate as well as the overall revenue per visitor (RPV). As Figure 4.3 shows, the winning version of the receiver selection element was not the new design but the original; however, the new versions emerged as winners for both the premium channel element and the add-ons further down on the page.

When Comcast integrated all three winning designs into the page and tested this revamped page against the original one, it found the changes drove a 4.6 percent lift in the purchase conversion rate and a 5.6 percent lift in RPV. The default and winning versions of the page are pictured in Figure 4.4.

Winner

+5.6% lift in RPV

+4.6% lift in purchase conversion rate

Figure 4.4 The default version of the page next to the redesigned page, which contains all the winning elements.

Because the impact of each element had been isolated, Comcast was also able to measure how much each one influenced the performance of the final version of the page: The premium channel element was the most influential, accounting for over 60 percent of the increase in RPV, indicating that, of the three elements tested, it was the original version of this feature that had presented the largest obstacle to customers completing their goals.

The main recommendation was to push the winning version of the page to all visitors. Additional proposals included running follow-up design tests of each variable to further simplify the user experience, starting with the premium channel element, because it had emerged as the most important one overall.

Take a Step Back

Although qualitative research is a key part of the ongoing design process, it can also play an invaluable role in helping to shape a company’s overall direction. Grounded in the customer perspective, qualitative research helps businesspeople to shape long-term strategies by keeping their finger on the pulse of an evolving marketplace, a practice that helps them develop better ways of fulfilling their customers’ needs in the present and in the future.

As businesspeople focus on the day-to-day activities related to delivering the same products and services, it’s easy to lose sight of the long-term customer needs that are driving the demand for those same products—a phenomenon renowned marketing savant Theodore Levitt called “marketing myopia.” Levitt argued that these companies tend to be “product-oriented instead of customer-oriented,” and view their “marketing effort” as a “necessary consequence of the product, not vice versa, as it should be.”

He cited the example of railroad companies: Once the titans of industry, they had fallen on hard times by the 1960s, all because they thought of themselves as being in the business of “railroads.” Had they instead seen themselves as being in the business of “transportation,” they would have begun to produce cars, trucks, airplanes, and even telephones—an expansion they were well positioned to tackle, given their extensive resources.

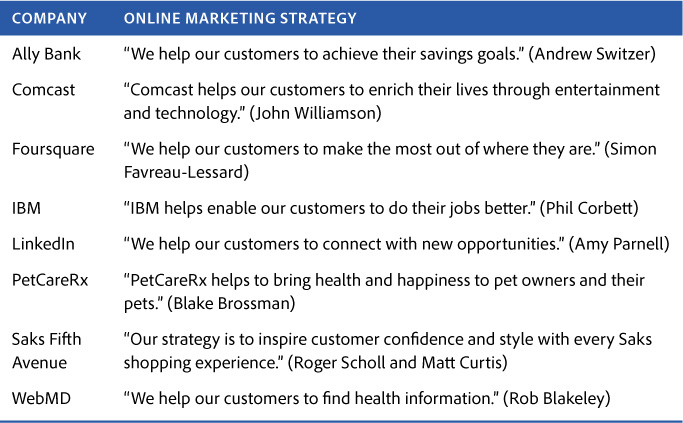

Levitt may have been writing in the 1960s, but his observations remain true: All too often, businesses focus on current successes instead of prioritizing their customers’ present—and future—needs. In recent years, however, some companies have grown to recognize the importance of building for the future; a few examples of well-developed marketing strategies, or long-term game plans for providing customer value, appear in Table 4.1.

Each strategy conveys a straightforward understanding of why customers come to the business for help that goes beyond the current core product and service offerings. For example, Comcast’s strategy to focus on entertainment and technology doesn’t keep the company tied to current revenue sources, such as cable lines or set-top boxes, because these will likely be short-lived due to rapidly evolving technology; indeed, Comcast has expanded its product offerings to allow customers to watch movies and television shows from mobile devices even when offline. Similarly, IBM’s online strategy is focused on work-related tasks for business customers; as such, IBM has expanded its services into cloud computing, “big data,” and social technologies.

All these examples illustrate the importance of preparing a pathway for the future—a journey that, in many cases, begins with asking solid qualitative-research questions and paying close attention to the answers.

Up Next

This chapter provided an overview of qualitative research techniques, which offer insights into customers’ goals and the challenges they face when trying to accomplish those goals. These insights lead to test ideas that will be added to the Optimization Roadmap, as well as inform the overall direction for a company.

The next chapter outlines quantitative research methods that companies use to verify qualitative findings, as well as to identify which site areas need improvement the most and what test ideas to prioritize as part of assembling the Optimization Roadmap.

References

1. “Marketing Myopia,” Harvard Business Review; Theodore Levitt (1960).