Chapter 4

Structure and Restructuring

A crisis over journalistic standards ensnared the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) in a flurry of parliamentary hearings, resignations, and public recrimination in 2004. The controversy so tarnished the respected institution's reputation that top officials took major steps to ensure that it would never happen again. The bevy of corrective changes included a journalism board to monitor editorial policy, guidelines on journalistic procedures, forms to flag trouble spots that managers were required to complete, and a 300‐page volume of editorial guidelines. The cumulative effect of the changes was a multilayered bureaucracy that limited managerial discretion and fostered a pecking order of approve‐disapprove boxes that were passed up the chain of command as an alternative to asking probing questions at lower levels in the organization.

Some cures make the patient worse, and this newly restructured system resulted in two crises more damaging than the first. In October 2012, the BBC came under heavy fire when it broadcast a glowing tribute to a well‐known former BBC TV host, Jimmy Savile, but killed an investigative report detailing evidence that Savile had been a serial child molester.

Reorganizing, or restructuring, is a powerful but high‐risk tactic for improving organizations. Also in 2012, the BBC aired a report wrongly accusing a member of Margaret Thatcher's government of being a pedophile. Post‐mortem investigations attributed this error and the Savile one directly to the BBC's restructured, highly bureaucratized system. Major initiatives to redesign structure and processes often prove neither durable nor beneficial. Designing a structure, putting all the disparate parts in place, specifying their connections and satisfying every interested party's interests is difficult and risky. Although restructuring is one of the most popular management strategies for improving performance, and more than half of new CEOs implement a reorganization in their first two years on the job (Blenko, Mankins, and Rogers, 2010), Boston Consulting Group (2021) reports that “more than half of companies rate their reorganization initiatives as ‘mostly’ or ‘very’ unsuccessful.”

But it is also true that, over the past 100 years, management tools like strategic planning, decentralization, capital budgeting techniques, and self‐governing teams have done more than any other kind of innovation to allow companies to cross new performance thresholds (Hamel, 2006). As an example, American automakers scratched their heads for 20 years trying to figure out what made Toyota so successful. They tried all kinds of process innovations but finally reached the conclusion that Toyota had simply given their employees more authority to make decisions and solve problems (Hamel, 2006).

An organization's structure at any moment represents its unique resolution of an enduring set of basic tensions or dilemmas, which we discuss next. Then, drawing on the work of Henry Mintzberg and Sally Helgesen, we illustrate two views of options organizations may consider in aligning structure with mission and environment. We conclude with case examples illustrating both opportunities and challenges that managers encounter when attempting to create more workable and fruitful structural designs.

STRUCTURAL DILEMMAS

Finding an apt confluence of authority, roles, and relationships is a universal struggle. Managers rarely face well‐defined problems with clear‐cut solutions. Instead, they confront enduring structural dilemmas—tough trade‐offs without easy answers.

Differentiation Versus Integration

The tension between assigning work and synchronizing different efforts creates a classic dilemma. The more complex a role configuration (lots of people doing many different things), the harder it is to sustain a focused, tightly coupled enterprise. As size and complexity grow, organizations need more sophisticated—and more costly—coordination strategies. Lateral strategies are needed to supplement top‐down rules, policies, and commands.

Gap Versus Overlap

If key responsibilities are not clearly assigned, important tasks typically fall through the cracks. Conversely, roles and activities can overlap, creating conflict, wasted effort, and unintended redundancy. A patient in a prestigious teaching hospital, for example, called her husband and pleaded with him to rescue her. She couldn't sleep at night because hospital staff, especially nurses' aides and interns, kept waking her, often to repeat a procedure or administer a medication that someone else had done a short time before. Conversely, when she wanted something, pressing her nurses' call button rarely produced a timely response.

The new cabinet‐level Department of Homeland Security created in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks was intended to reduce gaps and overlaps among the many agencies responsible for responding to domestic threats. Activities incorporated into the new department included immigration, border protection, emergency management, and intelligence analysis. Yet the two most prominent antiterrorism agencies, the FBI and the CIA—with their long history of mutual gaps, overlaps, and bureaucratic squabbling—remained separate and outside the new agency (Firestone, 2002).

Underuse Versus Overload

If employees have too little work, they become bored and get in other people's way. Members of the clerical staff in a physician's office were able to complete most of their tasks during the morning. After lunch, they filled their time talking to family and friends. As a result, the office telephone lines were constantly busy, making it difficult for patients to ask questions and schedule appointments. Meanwhile, clients and routine paperwork swamped the nurses, who were often brusque and curt because they were so busy. Patients complained about impersonal care. Reassigning many of the nurses' clerical duties to office staff created a better structural balance.

Lack of Clarity Versus Lack of Creativity

If employees are unclear about what they are supposed to do, they often tailor their roles to fit personal preferences instead of shaping them to meet system‐wide goals. This frequently leads to trouble. Most McDonald's customers are not seeking novelty and surprise in their burgers and fries. But when responsibilities are over‐defined, people conform to prescribed roles and protocols in “bureaupathic” ways. They rigidly follow job descriptions, regardless of how much the service or product suffers.

“You lost my bag!” an angry passenger shouted, confronting an airline manager.

The manager responded, “How was the flight?”

“I asked about my bag,” said the passenger.

“That's not my job,” the manager replied. “Check with baggage claim.”

The passenger did not come away as a satisfied customer.

Excessive Autonomy Versus Excessive Interdependence

If the efforts of individuals or groups are too independent, people often feel isolated. Schoolteachers may feel lonely and unsupported because they work in self‐contained classrooms and rarely see other adults. Forced to make a sudden shift to online teaching during the Covid pandemic, many teachers felt even more alone and burdened. One study found that more than 70 percent contemplated leaving the profession (Zalaznik, 2021). Yet efforts to create closer teamwork have repeatedly run aground because of teachers' difficulties in working together. In contrast, if too tightly connected, people in roles and units are distracted and waste time on unnecessary coordination. IBM lost an early lead in the personal computer business in part because new initiatives required so many approvals—from levels and divisions alike—that new products were overdesigned and late to market. The same problem hindered Hewlett‐Packard's ability to innovate in the late 1990s.

Too Loose Versus Too Tight

Another critical structural dilemma is how to hold an organization together without holding it back. If structure is too loose, people go astray, with little sense of what others are doing. But rigid structures stifle flexibility and encourage people to waste time trying to bolster or beat the system.

We can see some of the perils of a loose structure in the former accounting firm Andersen Worldwide, indicted in 2002 for its role in the Enron scandal. Efforts to shred documents and alter memos at Andersen's Houston office went well beyond questionable accounting procedures. At its Chicago headquarters, Andersen had an internal audit team, the Professional Standards Group, charged with reviewing the work of regional offices. Unlike other large accounting firms, Andersen let frontline partners closest to the clients overrule the internal audit team. This fostered local discretion that was a selling point to customers, including Enron, but came back to haunt the firm. As a result of the lax controls, “the rainmakers were given the power to overrule the accounting nerds” (McNamee and Borrus, 2002, p. 33). The august firm collapsed as a result.

The opposite problem is common in managed health care. Insurance companies give clerks far from the patient's bedside the authority to approve or deny treatment or to review medical decisions, often frustrating physicians and patients. Doctors lament spending time talking to insurance representatives that would be better spent seeing patients. Insurance providers sometimes deny treatments that physicians see as urgent. In one case, a hospital‐based psychologist diagnosed an adolescent as likely to commit sexual assault. The insurer questioned the diagnosis and denied hospitalization. The next day, the teenager raped a 5‐year‐old girl.

Goal‐less Versus Goal‐bound

In some situations, few people know what the goals are. In others, people cling intently to targets long after they have become irrelevant or outmoded, like the Japanese soldiers who hid on islands in the Pacific for decades after World War II, unaware that the war had been over since 1945. Conversely, the Salk vaccine virtually eradicated polio in the 1960s. This lauded medical breakthrough also brought to an end the existing strategy of the March of Dimes organization, which for years had championed finding a cure for the crippling disease. The organization rebounded by shifting its strategy to focus on preventing birth defects.

Irresponsible Versus Unresponsive

If people abdicate their responsibilities, performance suffers. However, adhering too rigidly to policies or procedures can be equally harmful. In public agencies, “street‐level bureaucrats” (Lipsky, 1980), who deal with the public, are often asked, “Could you do me this small favor?” or “Couldn't you bend the rules a little bit in this case?” Turning down every request, no matter how reasonable, alienates the public and perpetuates images of bureaucratic rigidity and red tape. But agency workers who are too accommodating create nagging problems of inconsistency and favoritism.

STRUCTURAL CONFIGURATIONS

Structural design rarely starts from scratch. Managers search for options and images among the vast array of possibilities drawn from their accumulated wisdom and experiences of others. Templates and frameworks can offer options to stimulate thinking. Henry Mintzberg and Sally Helgesen offer two abstract images of structural possibilities.

Mintzberg's Fives

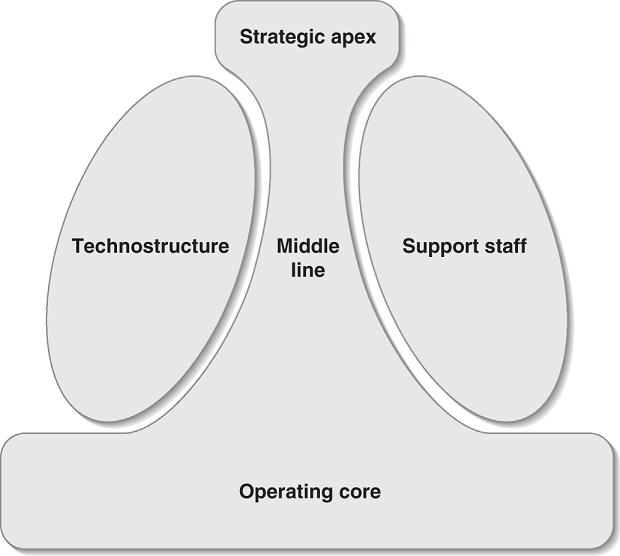

As the two‐dimensional lines and boxes of a traditional organization chart have become increasingly archaic, students of organizational design have developed a variety of new structural images. One influential example is Mintzberg's five‐sector “logo,” depicted in Exhibit 4.1. Mintzberg's model clusters various functions into groupings and displays their relative size and influence in response to different strategies and external circumstances. His schema provides a rough atlas of the fundamental terrain that can help managers get their bearings. It assists in sizing up the lay of the land before assembling a structure that conforms to prevailing circumstances. One of the distinctive features of Mintzberg's image is expanding the typical two‐dimensional view of structure into a more expansive rendering that provides a sharper image of the intricacy and issues of organization design.

Exhibit 4.1.

Mintzberg's Model.

Source: Mintzberg (1979, p. 20). Copyright ©1979. Reprinted by permission of Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

At the base of Mintzberg's image is the operating core, consisting of workers (agents) who produce or provide products or services directly to customers or clients: teachers in schools, assembly‐line workers in factories, physicians and nurses in hospitals, and flight crews in airlines.

Directly above the operating core is the administrative component: managers who supervise, coordinate, control, and provide resources for the operators. School principals, factory supervisors, and echelons of middle management fulfill this role. At the top of Mintzberg's figure, senior managers in the strategic apex track developments in the environment, determine the strategy, and shape the grand design. In school systems, the strategic apex includes superintendents and school boards. In corporations, nonprofits, and universities, the apex houses the board of directors and senior executives.

Two more components sit alongside the administrative component. The technostructure houses specialists, technicians, and analysts who standardize, measure, and inspect outputs and procedures. Accounting and quality control departments in industry, audit departments in government agencies, and flight standards departments in airlines perform such functions.

The support staff performs tasks that support or facilitate the work of others throughout the organization. In schools, for example, the support staff includes nurses, secretaries, custodians, food service workers, and bus drivers. These people often wield influence far greater than their station might suggest.

From this basic blueprint, Mintzberg (1979) derived five structural configurations: simple structure, machine bureaucracy, professional bureaucracy, divisionalized form, and adhocracy. Each creates its unique set of management challenges.

Simple Structure

New businesses typically begin as simple structures, with only two levels: the strategic apex and an operating level. Coordination is accomplished primarily through direct supervision and oversight, as in a small mom‐and‐pop operation. Mom or pop constantly monitor what is going on and exercise complete authority over daily operations. William Hewlett and David Packard began their business in a garage, as did Apple Computer's Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak. Simple structure has the virtues of flexibility and adaptability. One or two people control the operation and can turn on a dime when needed. But virtues can become vices. Authorities can block as well as initiate change, and they can punish capriciously as well as reward handsomely. A boss too close to day‐to‐day operations is easily distracted by immediate problems, neglecting long‐range strategic issues. A notable exception was Panasonic founder Konosuke Matsushita, who promulgated his 250‐year plan for the future of the business when his young company still had less than 200 employees.

Machine Bureaucracy

McDonald's is a classic machine bureaucracy. Members of the strategic apex make the big decisions. Managers and standardized procedures govern day‐to‐day operations. Like other machine bureaucracies, McDonald's has support staffs and a sizable technostructure that sets standards for the cooking time of French fries or the assembly of a Big Mac or quarter pounder.

For routine tasks, such as making hamburgers and manufacturing automotive parts, a machine‐like operation is efficient and effective. A key challenge is how to motivate and satisfy workers in the operating core. People quickly tire of repetitive work and standardized procedures. Yet offering too much creativity and personal challenge in, say, a McDonald's outlet could undermine consistency and uniformity—two keys to the company's success.

Like other machine bureaucracies, McDonald's deals constantly with tension between local managers and headquarters. Local concerns and tastes weigh heavily on decisions of middle managers. Top executives, aided by analysts armed with massive data, rely more on generic and abstract information. Their decisions are influenced by company‐wide concerns. As a result, a solution from the top may not always match the needs of individual units. Faced with declining sales and market share, McDonald's introduced a new food preparation system in 1998 under the marketing banner “Made for you.” CEO Jack Greenberg was convinced the cook‐to‐order system would produce the fresher, tastier burgers needed to get the company back on the fast track. However, franchisees soon complained that the new system led to long lines and frustrated customers. Unfazed by the criticism, Greenberg invited a couple of skeptical financial analysts to flip burgers at a McDonald's outlet in New Jersey so they could see firsthand that the concerns were unfounded. The experiment backfired. The analysts agreed with local managers that the system was too slow and decided to pass on the stock (Stires, 2002). The board replaced Greenberg at the end of 2002.

Professional Bureaucracy

Harvard University affords a glimpse into the inner workings of a professional bureaucracy. As in other organizations that employ large numbers of highly educated professionals, Harvard's operating core is large relative to other structural elements, although the technostructure has grown in recent years to accommodate mandated programs such as gender and racial equity. At the operating sphere, each individual school has substantial autonomy to chart its own course. Procedures for things like teaching evaluations that are typically campus‐wide at other universities are localized at Harvard. Few managerial levels exist between the strategic apex and the professors, creating a flat and decentralized profile.

Control relies heavily on professional training and indoctrination. Insulated from formal interference, professors have almost unlimited academic freedom to apply their expertise as they choose. Freeing highly trained experts to do what they do best produces many benefits but leads to challenges of coordination and quality control. Tenured professors, for example, are largely immune from formal sanctions. At Harvard, that has often protected senior faculty who were guilty of serial sexual harassment (Bikales, 2020). In the case of a professor whose teaching performance was moving from erratic to bizarre, a Harvard dean did the one thing he felt he could do—he relieved the professor of teaching responsibilities while continuing to pay his full salary. The dean was not disappointed when the professor quit in anger (Rosovsky, 1990).

A professional bureaucracy responds slowly to external change. Waves of reform typically produce little impact, because professionals often view any change in their surroundings as an annoying distraction. The result is a paradox: individual professionals may be at the forefront of their specialty, whereas the institution as a whole changes at a glacial pace. Professional bureaucracies regularly stumble when they try to exercise greater control over the operating core; requiring Harvard professors to follow standard teaching methods would produce a revolt and might do more harm than good.

Divisionalized Form

In a divisionalized organization (see Exhibit 4.2), the bulk of the work is done in semi‐autonomous units, such as freestanding campuses in a multi‐campus university, areas of expertise in a large multi‐specialty hospital, or independent business units in a Fortune 500 firm (Mintzberg, 1979). Johnson & Johnson, for example, is among the world's largest companies (#35 on the Fortune 500 in 2020). It has more than 275 operating companies lodged in over 60 countries. Its medical device division is the world's largest. Its pharmaceutical division is even bigger. Its consumer products division markets an assortment of well‐known brands like Neutrogena, Tylenol, Band‐Aids, and Rogaine.

Although J&J's divisions often have little in common, the company's executives argue that there is a level of shared synergy and stability that have paid off over time. Despite setbacks in the Tylenol crisis of 1982 and a series of product recalls in 2010 and 2012, J&J has raised its dividend every year for more than half a century and in 2020 was one of the last two U.S. companies still carrying a AAA credit rating.

Exhibit 4.2.

Divisionalized Form.

Source: Mintzberg (1979, p. 393). Copyright ©1979. Reprinted by permission of Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

One of the oldest businesses in the United States, Berwind Corporation began in coal‐mining in 1886. It now houses divisions in business sectors as diverse as manufacturing, financial services, real estate, and land management. Each division serves a distinct market and supports its own functional units. Division presidents are accountable to the corporate office in Philadelphia for specific results: profits, sales growth, and return on investment. As long as they deliver, divisions have relatively free rein. Philadelphia manages the strategic portfolio and allocates resources based on its assessment of market opportunities.

Divisionalized structure offers economies of scale, resources, and responsiveness while controlling economic risks, but it creates other tensions. One is a cat‐and‐mouse game between headquarters and divisions. Headquarters wants oversight, while divisional managers try to evade corporate control:

Our top management likes to make all the major decisions. They think they do, but I've seen one case where a division beat them. I received … a request from the division for a chimney. I couldn't see what anyone would do with a chimney … [But] they've built and equipped a whole plant on plant expense orders. The chimney is the only indivisible item that exceeded the $50,000 limit we put on plant expense orders. Apparently they learned that a new plant wouldn't be formally received, so they built the damn thing. (Bower, 1970, p. 189)

Another risk in independent divisions form is that headquarters may lose touch with operations. As one manager put it, “Headquarters is where the rubber meets the air.” Divisionalized enterprises become unwieldy unless goals are measurable and reliable information systems are in place (Mintzberg, 1979).

Adhocracy

Adhocracy is a loose, flexible, self‐renewing organic form tied together primarily through lateral means. Usually found in diverse, freewheeling environments, adhocracy functions as an “organizational tent,” exploiting benefits that structural designers traditionally regarded as liabilities: “Ambiguous authority structures, unclear objectives, and contradictory assignments of responsibility that can legitimize controversies and challenge traditions. Incoherence and indecision can foster exploration, self‐evaluation, and learning” (Hedberg, Nystrom, and Starbuck, 1976, p. 45). Inconsistencies and contradictions in an adhocracy become paradoxes whereby a balance between opposites protects an organization from falling into an either‐or trap.

Ad hoc structures thrive in conditions of turbulence and rapid change. Examples are advertising agencies, think‐tank consulting firms, and the recording industry. A successful and durable example of an adhocracy is W. L. Gore, producer of Gore‐Tex, vascular stents, dental floss, and many other products built on its pioneering development of advanced polymer materials. When he founded the company in 1958, Bill Gore conceived it as an organization where “there would be no layers of management, information would flow freely in all directions, and personal communications would be the norm. And individuals and self‐managed teams would go directly to anyone in the organization to get what they needed to be successful.” (Hamel, 2010).

Half a century later, Gore has more than 10,000 employees (Gore calls them “associates”) and some $3 billion in annual sales, but still adheres to Bill Gore's principles. In Gore's “lattice” structure, people don't have bosses. Instead, the company relies on “natural leaders”—individuals who can attract talent, build teams, and get things done. One test: if you call a meeting and no one comes, you're probably not a leader. When Gore's CEO retired in 2005, the board polled associates to find out whom they would be willing to follow. They weren't given a slate—they could nominate anyone. No one was more surprised than Terri Kelly when she became the people's choice. She acknowledges that Gore's approach carries a continuing risk of chaos. It helps, she says, that the culture has clear norms and values, but

Our leaders have to do an incredible job of internal selling to get the organization to move. The process is sometimes frustrating, but we believe that if you spend more time up front, you'll have associates who are not only fully bought‐in, but committed to achieving the outcome. Along the way, they'll also help to refine the idea and make the decision better. (Hamel, 2010)

Helgesen's Web of Inclusion

Mintzberg's five‐sector imagery adds a new dimension to the conventional line‐staff organization chart but retains some of the traditional image of structure as a top‐down pyramid. Helgesen argues that the idea of hierarchy is primarily a male‐driven depiction, quite different from structures created by female executives:

The women I studied had built profoundly integrated and organic organizations in which the focus was on nurturing good relationships; in which the niceties of hierarchical rank and distinction played little part; and in which lines of communication were multiplicitous, open, and diffuse. I noted that women tended to put themselves at the center of their organizations rather than at the top, thus emphasizing both accessibility and equality, and that they labored constantly to include people in their decision‐making. (Helgesen, 1995, p. 10)

Helgesen coined the expression “web of inclusion” to depict an organic form more circular than hierarchical. The web builds from the center out. Its architect works much like a spider, spinning new threads of connection and reinforcing existing strands. The web's center and periphery are interconnected; action in one place ripples across the entire configuration, forming “an interconnected cosmic web in which the threads of all forces and events form an inseparable net of endlessly, mutually conditioned relations” (Fritjof Capra, quoted in Helgesen, 1995, p. 16). Consequently, weaknesses in either the center or the periphery of the web undermine the strength of the natural network.

A famous example of web organization is “Linux, Inc.,” the loose organization of individuals and organizations that has formed around Linus Torvalds, the creator of the open‐source operating system Linux, whose many variants power most of the world's supercomputers, cell phones, stock markets, and web domains. “Linux, Inc.” is anything but a traditional company:

There's no headquarters, no CEO, and no annual report. It's not a single company, but a cooperative venture. More than 13,000 developers from more than 1,300 companies along with thousands of individual volunteers have contributed to the Linux code. The Linux community, Torvalds says, is like a huge spider web, or better yet, multiple spider webs representing dozens of related open‐source projects. His office is “near where those webs intersect.” (Hamm, 2005)

Freewheeling web or lattice structures may encounter increasing challenges as an organization gets bigger. When Meg Whitman became CEO of Internet phenomenon eBay in 1998, she joined an organization of fewer than fifty employees configured in an informal web around founder Pierre Omidyar. When she tried to set up appointments with her new staff, she was surprised to learn that scheduled meetings were a foreign concept in a company where no one kept a calendar. Omidyar had built a company with a strong culture and powerful sense of community but no explicit strategy, no regular meetings, no marketing department, and almost no other identifiable structural elements. Despite the company's phenomenal growth and profitability, Whitman concluded that it was in danger of imploding without more structure and discipline. Omidyar agreed. He had worked hard to recruit Whitman because he believed she brought the big‐company management experience that eBay needed to keep growing (Hill and Farkas, 2000).

GENERIC ISSUES IN RESTRUCTURING

Eventually, internal or external changes force every structure to adjust, but structural change is rarely easy. When the Roman Catholic Church elevated a new pope, Francis I, in March, 2013, many hoped that he would represent a breath of fresh air after the troubled reign of his predecessor. But a well‐placed insider noted how difficult this would be, even for a supposedly‐absolute ruler: “There have been a number of Popes in succession with different personalities, but the structure remains the same. Whoever is appointed, they get absorbed by the structure. Instead of you transforming the structure, the structure transforms you” (Donadio and Yardley, 2013).

When the time for restructuring comes, managers need to take account of tensions specific to each structural configuration. Consultants and managers often apply general principles and specific answers without recognizing key differences across architectural forms. Reshaping an adhocracy, for example, is different from restructuring a machine bureaucracy, and reweaving a web is very different from nudging a professional bureaucracy. Falling victim to the one‐best‐system or one‐size‐fits‐all mentality is a route to disaster. But the comfort of a well‐defined prescription lulls too many managers into a temporary comfort zone. They don't see the iceberg looming ahead until they crash into it.

Mintzberg's imagery depiction suggests general principles to guide restructuring across a range of circumstances. Each major component of his model exerts its own pressures. Restructuring triggers a multidirectional tug‐of‐war that eventually determines the shape of the emerging configuration. The result may be a catastrophe, unless leaders recognize and manage various pushes and pulls.

The strategic apex—top management—tends to exert centralizing pressures. Through commands, rules, or less obtrusive means, top managers continually try to develop a unified mission or strategy. Deep down, they long for a simple structure they can control. By contrast, middle managers resist control from the top and tend to pull the organization toward balkanization. Navy captains, school principals, plant managers, department heads, and bureau chiefs become committed to their own domain and seek to protect and enhance their unit's parochial interests. Tensions between centripetal forces from the top and centrifugal forces from middle management are especially prominent in divisionalized structures but are critical issues in any restructuring effort.

The technostructure exerts pressures to standardize; analysts love discipline and hate anarchy. They want to measure and monitor the organization's progress against well‐defined criteria. Depending on the circumstances, they counterbalance (or complement) top administrators, who want to centralize, and middle managers, who seek greater autonomy. A college professor who wants to use a web‐based simulation game, for example, may find that it takes weeks or months to negotiate the rules and procedures that the university's information technology units have put in place. Issues that seem critical to IT may seem like trivial annoyances to the professor, and vice versa. Technocrats feel most at home in a machine bureaucracy.

The support staff pulls in the direction of greater collaboration. Its members usually feel happiest when authority is dispersed to small work units. There they can influence, directly and personally, the shape and flow of everyday work and decisions. In one university, a new president created a new governance structure that, for the first time, included support staff along with faculty and administrators. The staff loved it, but when they came up with a proposal for improvements to the promotion and tenure process, the faculty was not amused. Meanwhile, the operating core seeks to control its own destiny and minimize influence from the other components. Its members often look outside—to a union or to their professional colleagues—for support.

Attempts to restructure must acknowledge the natural tensions among these competing interests. Depending on the configuration, any component may have more or less influence on the final outcome. In a simple structure, the boss has the edge. In machine bureaucracies, the techno structure and strategic apex possess the most clout. In professional bureaucracies, chronic conflict between administrators and professionals is the dominant tension, while members of the techno structure play an important role in the wings. In the adhocracy, a variety of actors can play a pivotal role in shaping the emerging structural patterns.

Beyond internal negotiations lurks a more crucial issue. A structure's workability ultimately depends on its fit with the organization's strategy, environment, and technology. Natural selection weeds out the field, determining survivors and victims. The major players must negotiate a structure that meets the needs of each component and still enables the organization to survive, if not thrive.

WHY RESTRUCTURE?

Restructuring is a challenging process that consumes time and resources with no guarantee of success, as the BBC case at the beginning of the chapter illustrates. Organizations typically embark on that path when they feel compelled to respond to major problems or opportunities. Various pressures can lead to that conclusion:

- The environment shifts. For Ma Bell (American Telephone & Telegraph), once the telephone company for most of the United States, a mandated shift from regulated monopoly to a market with multiple competitors required a massive reorganization that played out over decades. When AT&T split off its local telephone companies into regional “Baby Bells,” few anticipated that eventually one of the children (Southwest Bell) would swallow up the parent and appropriate its identity.

- Technology changes. The aircraft industry's shift from piston to jet engines profoundly affected the relationship between engine and airframe. Some established firms faltered because they underestimated the complexities; Boeing rose to lead the industry because it understood the issues (Henderson and Clark, 1990).

- Organizations grow. Digital Equipment thrived with a very informal and flexible structure during the company's early years, but the same structure produced major problems when it grew into a multibillion‐dollar corporation.

- Leadership changes. Reorganization is often the first initiative of new leaders. It is a way for them to try to put their stamp on the organization, even if no one else sees a need to restructure.

Miller and Friesen (1984) studied a sample of successful as well as troubled firms undergoing structural change and found that those in trouble typically fell into one of three configurations:

- The impulsive firm: A fast‐growing organization, controlled by one individual or a few top people, in which structure and controls have become too primitive and the firm is increasingly out of control. Profits may fall precipitously, and survival may be at stake. Many once‐successful entrepreneurial organizations stumble at this stage because they have failed to evolve beyond their simple structure.

- The stagnant bureaucracy: An older, tradition‐dominated organization with an obsolete product line. A predictable and placid environment has lulled everyone to sleep, and top management is slavishly committed to old ways. Management thinking is too rigid or information systems are too primitive to detect the need for change, and lower‐level managers feel ignored and alienated. Many old‐line corporations and public agencies fit into this group of faltering machine bureaucracies.

- The headless giant: A loosely coupled, divisional organization that has turned into a collection of feudal baronies. The administrative strategic apex is weak, and most of the initiative and power resides in autonomous divisions. With little strategy or leadership at the top, the firm is adrift. Collaboration is minimal because departments compete for resources. Decision making is reactive and crisis‐oriented. WorldCom is an example of how bad things can get in this situation. CEO Bernie Ebbers built the company rapidly from a tiny start‐up in Mississippi to a global telecommunications giant through some sixty‐five acquisitions. But

for all its talent in buying competitors, the company was not up to the task of merging them. Dozens of conflicting computer systems remained, local network systems were repetitive and failed to work together properly, and billing systems were not coordinated. “Don't think of WorldCom the way you would of other corporations,” said one person who has worked with the company at a high level for many years. “It's not a company, it's just a bunch of disparate pieces. It's simply dysfunctional.” (Eichenwald, 2002, p. C‐6)

Miller and Friesen (1984) found that even in troubled organizations, structural change is episodic: long periods of little change are followed by brief episodes of major restructuring. Organizations are reluctant to make major changes because a stable structure reduces confusion and uncertainty, maintains internal consistency, and protects the existing equilibrium. The price of stability is a structure that grows increasingly misaligned with the environment. Eventually, the gap gets so big that a major overhaul is inevitable. Restructuring, in this view, is like spring cleaning: we accumulate debris over months or years until we are finally forced to face up to the mess.

MAKING RESTRUCTURING WORK: TWO CASE EXAMPLES

In this section, we look at two case examples of restructuring. Some represent examples of reengineering, which rose to prominence in the 1990s as an umbrella concept for emerging trends in structural thinking. Hammer and Champy promised a revolution in how organizations were structured:

When a process is reengineered, jobs evolve from narrow and task oriented to multidimensional. People who once did as they were instructed now make choices and decisions on their own instead. Assembly‐line work disappears. Functional departments lose their reason for being. Managers stop acting like supervisors and behave more like coaches. Workers focus more on customers' needs and less on their bosses' whims. Attitudes and values change in response to new incentives. Practically every aspect of the organization is transformed, often beyond recognition. (1993, p. 65)

More than half of all Fortune 500 companies jumped on the reengineering bandwagon in the mid‐1990s, but only about a third of those efforts were successful. Champy admitted in a follow‐up book, Reengineering Management (1995), that reengineering was in trouble, and attributed the shortfall to flaws in senior management thinking.

Some reengineering initiatives have indeed been catastrophic, a notorious example being the long‐haul bus company Greyhound Lines. As the company came out of bankruptcy in the early 1990s, a new management team announced a major reorganization, with sizable cuts in staffing and routes and development of a new, computerized reservation system. The initiative played well on Wall Street, where the company's stock soared, but poorly on Main Street as customer service and the new reservations system collapsed. Rushed, underfunded, and insensitive to both employees and customers, it was a textbook example of how not to restructure. Eventually, Greyhound's stock crashed, and management was forced out. One observer noted wryly, “They reengineered that business to hell” (Tomsho, 1994, p. A1). Across many organizations, reengineering was camouflage for downsizing the workforce, often with disappointing results.

Nevertheless, despite the many disasters, there have also been examples of notable restructuring success. Here we discuss two of them, drawn from different industries.

Principles of Successful Structural Change

Too many efforts to change structure fail. The Beth Israel, and Ford Motor Company initiatives succeeded by following several basic principles of successful structural change:

- They did the hard work of carefully studying the existing structure and process so that they fully understood how things worked—and what wasn't working. (Many efforts at structural change fail because they start from an inadequate picture of current roles, relationships, and processes.)

- The change architects developed a new conception of the organization's goals and strategies attuned to the challenges and circumstances of the time.

- They designed the new structure in response to changes in strategy, technology, and environment.

- Finally, they experimented as they moved along, retaining things that worked and discarding those that did not.

CONCLUSION

At any given moment, an organization's structure represents its best effort to align internal activities with outside pressures and opportunities. Managers work to juggle and resolve enduring organizational dilemmas: Are we too loose or too tight? Are employees underworked or overwhelmed? Are we too rigid, or do we lack standards? Do people spend too much or too little time harmonizing with one another? Structure represents a resolution of contending claims from various groups.

Mintzberg differentiates five major components in organizational structure: strategic apex, middle management, operating core, techno structure, and support staff. These components configure in unique designs: machine bureaucracy, professional bureaucracy, simple structure, divisionalized form, and adhocracy. Helgesen adds a less hierarchical model, the web of inclusion.

Changes, whether driven from inside or outside, eventually require some form of structural adaptation. Restructuring is a sensible but high‐risk move. In the short term, structural change invariably produces confusion and resistance; things get worse before they get better. In the end, success depends on how well the new model aligns with environment, task, and technology. It also hinges on the route taken in putting the new structure in place. Effective restructuring requires both a fine‐grained, microscopic assessment of typical problems and an overall, topographical sense of structural options. Putting the most talented people in a confused or inappropriate structure is a sure route to failure.