Chapter 6. Automating communication

- Sending email

- Processing email

- Exchanging messages with AIM

- Exchanging messages with Jabber/XMPP

With the proliferation of communication technologies like the telephone, the internet, and cell phones, people are more connected than ever before, and recent software advances have allowed us to automate these communications: electronic call center menus, widespread email, instant messaging (IM) bots, and so on. This sort of communications automation software can make your life much easier when it comes to handling interactions with coworkers, employees, and customers. For example, you might want to send out an email to 500 customers when their product has shipped. As invisible and minor as this software seems, it is a very big piece of the infrastructure of modern businesses.

In this chapter, we’ll look at techniques for creating this sort of software, looking at code examples extracted from real systems doing this sort of work every day. We’ll start by looking at email, discussing how to send, receive, and process it. Then we’ll take a look at some instant communication mediums, such as AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) and Jabber.

6.1. Automating email

Email is one of the most popular technologies on the web today, but, thanks to spammers, the concept of “automated email dispersion” has bad connotations, even though this sort of mechanism is probably one of the most common internet applications. It’s often used in consumer applications. Purchased a product from an online shop? Chances are you’ve received an automatically generated email message. Signed up for a new service lately? You’ve probably received an activation notice via email.

But these are all business-to-consumer use cases. What about automating email for things like your continuous integration server or process-monitoring software? You can use email as a powerful way to alert or update people about the state of a system. You could also use automated email reception for tasks like creating new tickets in your development ticketing system or setting up autoresponders for email addresses (for example, a user sends an email to [email protected], and then emails are automatically responded to with the message in the body for that address). Email’s ubiquity makes it a powerful tool for communication in your Ruby applications, and in this section we’ll show you how to harness email to do your (Ruby-powered) bidding. We’ll cover the basics, like sending and receiving, and then look at processing email with Ruby.

Let’s first take a look at your options for sending email messages with Ruby.

6.1.1. Automating sending email

Ruby has a few options for sending email messages. First, there’s a built-in library, Net::SMTP, which is very flexible but also very difficult to use compared with others. There are also other high-level solutions such as TMail or Action Mailer (built on top of TMail), which work just fine, but we’ve found that a gem named MailFactory works the best. MailFactory gives you nice facilities for creating email messages while requiring very little in the way of dependencies.

Testing SMTP

If you don’t have an SMTP server like Sendmail handy, then Mailtrap is for you. Written by Matt Mowers, Mailtrap is a “fake” SMTP server that will write (or “trap”) the messages to a text file rather than sending them. You can grab Mailtrap via RubyGems (gem install mailtrap) or download it and find out more at rubyforge.org/projects/rubymatt/.

Problem

You need to automate sending email from your Ruby application to alert your system administrators when Apache crashes.

Solution

Ruby’s built-in SMTP library is fairly low-level, at least in the sense that it makes you feed it a properly formatted SMTP message rather than building it for you. MailFactory is a library (available via RubyGems) that helps you generate a properly formatted message, which you can then send via the built-in SMTP library.

Creating a message with MailFactory is as simple as creating a MailFactory object, setting the proper attributes, and then getting the object’s string value, a properly formatted SMTP message. Listing 6.1 shows a short example.

Listing 6.1. Constructing a basic MailFactory object, attribute by attribute

As you can see, setting up a MailFactory object is fairly straightforward: instantiate, populate, and output the message to a string.

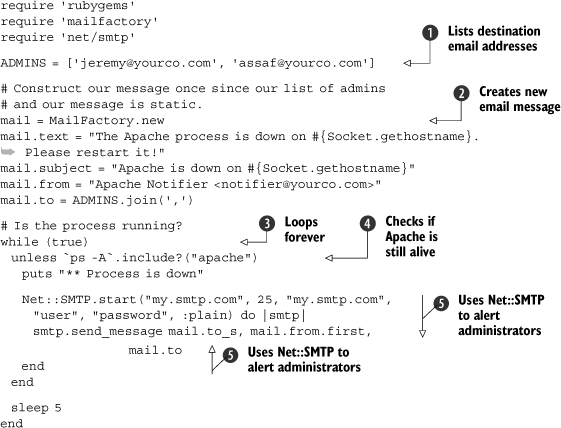

Now, all you need to do is feed the message to Net::SMTP to send it. To send an email to your system administration team every time your Apache web server process crashes, you just need to build a MailFactory object, giving it a string of recipients, and then send it via Net::SMTP. Listing 6.2 shows our implementation.

Listing 6.2. Sending email to administrators

First, we build an array of administrator email addresses ![]() . Then we use this and other information to build the MailFactory object

. Then we use this and other information to build the MailFactory object ![]() . Next, we constantly loop like a daemon

. Next, we constantly loop like a daemon ![]() (we could also take this out and run the script in a cron job or something like that), grabbing the output of ps

(we could also take this out and run the script in a cron job or something like that), grabbing the output of ps ![]() and checking it for the term “apache.” If it’s not found, we send a mail to the administrators using Net::SMTP

and checking it for the term “apache.” If it’s not found, we send a mail to the administrators using Net::SMTP ![]() . The start method takes parameters for the SMTP server address and port, the “from” domain, your username and password, and the authentication scheme (could be :plain, :login, or :cram_md5). An SMTP object is then yielded to the block, which we can call methods on to send email messages (e.g., send_message).

. The start method takes parameters for the SMTP server address and port, the “from” domain, your username and password, and the authentication scheme (could be :plain, :login, or :cram_md5). An SMTP object is then yielded to the block, which we can call methods on to send email messages (e.g., send_message).

Discussion

We like to use MailFactory to build the SMTP message like this, but it’s not required. If you’re comfortable building properly formatted messages or are grabbing the messages from another source, MailFactory isn’t required. There are also alternatives to MailFactory, like TMail, which both generates and parses email messages. You don’t even have to use the built-in library for sending messages; if you’re really masochistic, you could just use a TCPSocket and talk SMTP directly!

SMS messages

A lot of cell phone carriers let you send SMS messages via email. This is a cheap and efficient way to reach people instantly when one of the options discussed later isn’t available.

One thing to note about our example is that it likely won’t work on Windows. The ps utility is a *nix-specific utility, which means that if you’re on Linux, Solaris, or Mac OS X, you should be fine, but if you’re on Windows, you’re out of luck. If you really want to implement something like this on Windows, you can take a few other routes. One is to use one of the many WMI facilities available, either through the win32 library or one of the other WMI-specific packages. You could also seek out a ps alternative on Windows, many of which are available if you just do a web search for them.

If these approaches strike you as too low-level, then Action Mailer might be for you. Action Mailer is Ruby on Rails’ email library, and it offers a lot of niceties that other approaches don’t. This isn’t a book all about Rails, so we won’t go into Action Mailer here, but if you’re interested, you can check out a book dedicated to Rails or the Action Mailer documentation at am.rubyonrails.org.

Now that you’re familiar with sending email with Ruby, let’s take a look at receiving it.

6.1.2. Receiving email

Ruby has built-in libraries for both POP3 and IMAP reception of messages, but unfortunately they’re not API-compatible with one another. In this section, we’re only interested in processing incoming emails quickly. We don’t intend to keep them around, so we don’t need the more advanced IMAP.

We’re going to concentrate on the POP3 library (Net::POP3), but if you’re interested, the example is available for the IMAP library in the downloadable source code for this book.

Problem

You need to perform actions at a distance, like being able to restart the MySQL server when away from the office. You don’t always have SSH access, but you can always email from a cell phone.

Solution

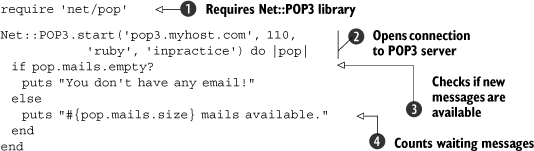

Ruby’s POP3 library, Net::POP3, is fairly simple to operate. To grab the messages from your inbox, you simply use the start method on the Net::POP3 class and manipulate the object given to its block. Check out the example in listing 6.3.

Listing 6.3. Fetching email using POP3

Net::POP3, like Net::SMTP and all other Net modules, is part of the Ruby standard library, which ships with every Ruby implementation. Unlike core library modules (like String, Array, and File) you have to require standard library modules in order to use them ![]() . Once you’ve gotten the library properly in place, you can take a few approaches to getting your mail. You could instantiate an object and work with it, but we think our approach here (using the class method and a block) is cleaner and more concise

. Once you’ve gotten the library properly in place, you can take a few approaches to getting your mail. You could instantiate an object and work with it, but we think our approach here (using the class method and a block) is cleaner and more concise ![]() . The parameters for the start method are the connection’s credentials: host, port, login, and password. Next, we interact with the object yielded to the block to see how many messages are present in the current fetch. If there are no email messages, we output a message indicating as much

. The parameters for the start method are the connection’s credentials: host, port, login, and password. Next, we interact with the object yielded to the block to see how many messages are present in the current fetch. If there are no email messages, we output a message indicating as much ![]() , but otherwise we output how many messages were found

, but otherwise we output how many messages were found ![]() .

.

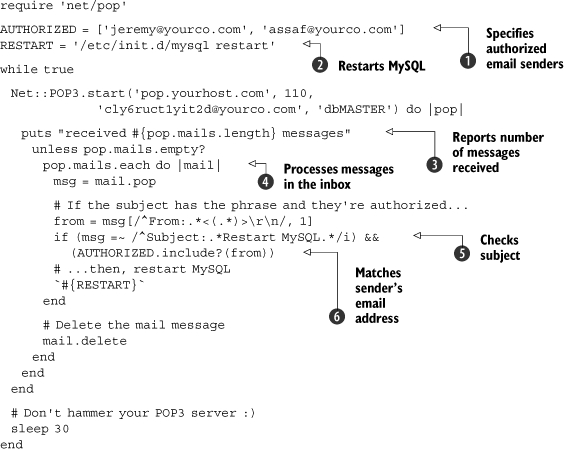

For this problem, we need to set up a system that will restart a MySQL server when a message is sent to a specific email address with the subject “Restart MySQL.” To build a system like that, we need to grab the emails from the address’s inbox, iterate through them, and check each message for “Restart MySQL” in the subject. You can see our implementation in listing 6.4.

Listing 6.4. Restarting MySQL via email

First, we set up a couple of constants: one for the email addresses that are authorized to restart MySQL ![]() , and one for the command we’ll use to restart MySQL

, and one for the command we’ll use to restart MySQL ![]() . Next, we output a message telling how many messages we’ve received

. Next, we output a message telling how many messages we’ve received ![]() . We then iterate through the messages

. We then iterate through the messages ![]() , checking for the proper subject

, checking for the proper subject ![]() and From address

and From address ![]() . If the sender is authorized and the subject contains “Restart MySQL,” we run RESTART and MySQL is restarted. Having read the message, we discard it and sleep for 30 seconds before checking to see if another message is waiting for us.

. If the sender is authorized and the subject contains “Restart MySQL,” we run RESTART and MySQL is restarted. Having read the message, we discard it and sleep for 30 seconds before checking to see if another message is waiting for us.

Discussion

The production system that this solution is based on had a few more things that administrators could do via email, such as managing indexes and creating databases. It also allowed administrators to send multiple commands per email. But we decided to strip this solution down to give you a base to work from that you can expand or completely change to suit your whim. You could change this to manage other long-running processes, execute one-off jobs, or even send other emails out.

You’re probably wondering about security. We wanted to make it possible to send an email from any device, specifically from cell phones. Even the simplest of cell phones lets you send short emails, usually by sending a text message (SMS) to that address instead of a phone number. You can try it out yourself if you have any email addresses in your phone book.

Unfortunately, cell phones won’t allow you to digitally sign emails, so we can’t rely on public/private key authentication. We can’t rely on the sender’s address either, because those are too easy to guess and forge. Instead, we used a unique inbox address that can survive a brute force attack and gave it only to our administrators. We kept this example short, but in a real application we’d expect better access control by giving each administrator his own private inbox address and an easy way to change it, should he lose his phone.

In spite of that, it’s always a good idea to double-check the sender’s address. We’ll want our task to send back an email response, letting the administrator know it completed successfully. And sometimes these responses come bouncing back, so we’ll need a simple way to detect administrator requests and ignore bouncing messages, or we’ll end up with a loop that keeps restarting the server over and over.

POP3 is usually good enough for most instances, but on some networks APOP (Authenticated POP) is required. If your host uses APOP authentication, you can give the start command a fifth Boolean parameter to indicate that Net::POP3 should use APOP. If we wanted to enable APOP on our previous example, the call to the start method would look something like this:

Net::POP3.start('pop.yourhost.com', 110, '[email protected]', 'dbMASTER', true) |

In this example, we extracted information from the raw POP message using regular expressions. This works for simple cases, like what we’ve done here, but as your needs get more complicated, the viability of this approach breaks down. In the next section, we’ll take a look at a much more robust solution to email processing: the TMail library.

6.1.3. Processing email

Now that you know how to send and receive email, you can start thinking about how to leverage these techniques to solve bigger problems. In this section, we’ll combine these two techniques and take a look at one subsystem in a production ticketing system.

Problem

You have a ticketing system built with Rails. It’s running great, but creating tickets is a bit laborious, so you want to allow users to open tickets via email. You need to process and respond to ticket-creation email messages in your Ruby application.

Solution

The smartest flow for the new ticket-creation system seems to be to receive an email, process its contents, put the relevant data in an instance of your model, and delete the mail. Then, pull the model on the front end with a web interface. So, we’ll assume you have a Ticket model like the following:

class Ticket < ActiveRecord::Base has_many :responses end |

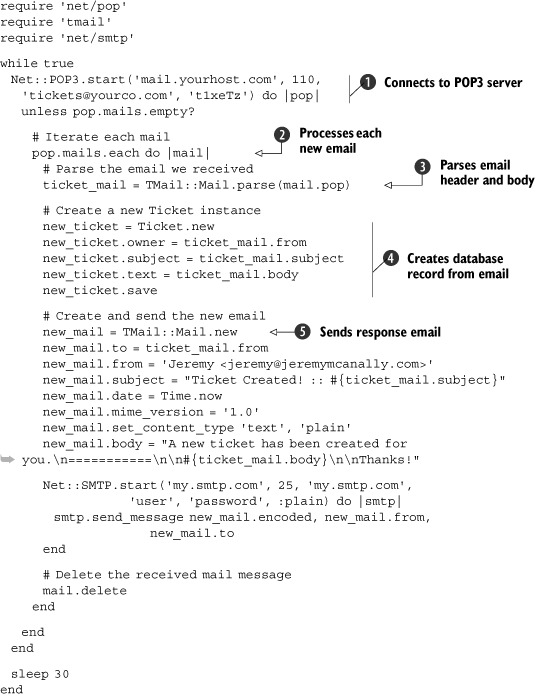

Listing 6.5 shows our implementation of the mail-handling script. We’ll analyze it piece by piece.

Listing 6.5. Creating tickets via email

In this implementation, we first receive our email messages using Net::POP3 ![]() . Then we iterate through the messages

. Then we iterate through the messages ![]() and use TMail’s message-parsing abilities to get a usable object with attributes

and use TMail’s message-parsing abilities to get a usable object with attributes ![]() . We then create a new instance of our ActiveRecord model, Ticket

. We then create a new instance of our ActiveRecord model, Ticket ![]() , and populate it with the data from the email. Finally, we use TMail to build a new email object (notice the API similarities to MailFactory)

, and populate it with the data from the email. Finally, we use TMail to build a new email object (notice the API similarities to MailFactory) ![]() , and send that email using Net::SMTP.

, and send that email using Net::SMTP.

Discussion

TMail is available as a standalone gem (gem install tmail), but you’ll also find it as part of the standard Rails distribution, included in the Action Mailer module. Action Mailer itself is a wrapper around TMail and Net::SMTP that uses the Rails framework for configuration and template-based email generation. You can learn more about Action Mailer from the Rails documentation. In this particular example, the email message was simple enough that we didn’t need to generate it from a template, and we chose to use TMail directly.

Note

Astrotrain Jeremy’s coworkers at entp have written a great tool named Astrotrain, which turns emails into HTTP posts or Jabber messages for further processing. You can send an email to [email protected] and get a post to something like http://yourhost.com/update/?token=my_token&hash=1234. You can find out more and get the source at http://hithub.com/entp/astrotrain/tree/master.

Now that you have a solid grasp of automating email, let’s take a look at another problem domain in communication automation: instant messaging.

6.2. Automating instant communication

Sometimes, email just isn’t quick enough. Thanks to technologies like online chat and instant messaging, we can now be connected directly with one another, chatting instantly. And the ubiquity of technologies like AIM, Jabber, and others finally make them a viable solution for business communication. Automating these sorts of communications opens up interesting possibilities: customer service bots, instant notification from your continuous integration system, and so on.

This section will concentrate on using two of the most popular options for instant communication: AIM and Jabber.

6.2.1. Sending messages with AIM

Once released independently of the America Online dial-up client, the IM component of the AOL system quickly became one of the most popular systems for private messaging. It might not have the same tech appeal as Jabber or GTalk, but it’s an instant messaging workhorse that commands half the market share and is used for both personal and business accounts. Contacting users or employees through AIM is a good way to make sure your communication is heard as quickly as possible.

Problem

You need to send server information via instant messages using AIM.

Solution

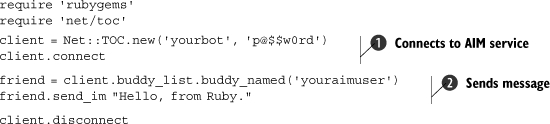

The Net::TOC library (gem install net-toc) provides a very flexible API for interacting with the AIM service. The first approach you can take to using it is a simple, procedural connect/send/disconnect approach. Listing 6.6 shows an example of sending an IM.

Listing 6.6. Sending an IM with Net::TOC

First, we create an object and connect to the AIM service ![]() . Then we find a user (in this case, “youraimuser”), send a simple message

. Then we find a user (in this case, “youraimuser”), send a simple message ![]() , and disconnect from AIM. This approach works well when you’re simply sending messages, but it gets awkward when you want to deal with incoming messages.

, and disconnect from AIM. This approach works well when you’re simply sending messages, but it gets awkward when you want to deal with incoming messages.

Fortunately, Net::TOC has a nice callback mechanism that allows you to respond to events pretty easily. These events range from an IM being received to a user becoming available. See table 6.1 for a full listing.

Table 6.1. A full listing of the Net::TOC callbacks

Callback | Description |

|---|---|

on_error {|err| } | Called when an error occurs. Use this to provide your own error-handling logic. |

on_im {|message, buddy, | Called when an IM is received; parameters include IM message and sender. Use this to receive and respond to messages. |

friend.on_status(status) { } | Called when the given friend’s status changes; the status parameter should be one of the following: :available, :online, :idle, :away. Use this to track when friends go online or offline and to see changes in their status message. |

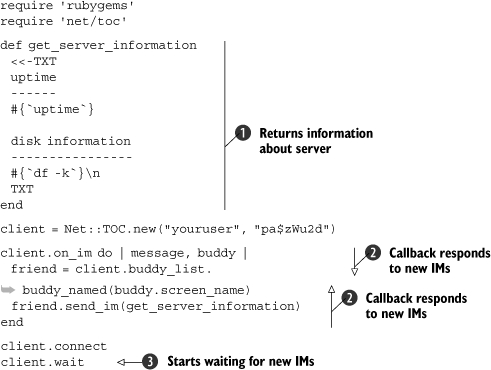

These callbacks make interactions with users much cleaner than if you tried to shoehorn them into the sequential method. Let’s say you wanted to get information from a server simply by sending an IM to an AIM bot. Listing 6.7 shows an implementation using Net::TOC’s callbacks.

Listing 6.7. Sending the results of uptime over AIM

To get the server information, we create a get_server_information method ![]() . Next, we use the on_im callback to respond to any IMs we receive

. Next, we use the on_im callback to respond to any IMs we receive ![]() . The callbacks basically function as a declarative way to define behavior when something happens, and, as you can see here, the block we provide will be called when an IM is received. When this happens, the buddy is found (to get a Net::TOC::Buddy object) and an IM is sent via the send_im method. Finally, once the callback is set up, we connect and wait for IMs to come in to fire the callback

. The callbacks basically function as a declarative way to define behavior when something happens, and, as you can see here, the block we provide will be called when an IM is received. When this happens, the buddy is found (to get a Net::TOC::Buddy object) and an IM is sent via the send_im method. Finally, once the callback is set up, we connect and wait for IMs to come in to fire the callback ![]() .

.

Discussion

Little bots and automations like this are becoming more and more popular. Developers are beginning to realize the potential uses for them: information lookups, customer management, workflows, and so on. Many IRC channels for open source packages (including Ruby on Rails) now have IRC bots that will give you access to a project’s API by simply sending a message like “api ActionController#render.” Developers looking for a solution to handle peer and management approval in code reviews or to alert their coworkers of Subversion activity could use an AIM bot like this one.

If you’re interested in embedding AIM chat features in a Rails application, your options are slim and aren’t very slick, but it is possible. We’re not aware of any Rails plugins that currently handle AIM communications dependably. The best way we’ve found to handle this is to build an external daemon that you integrate with your Rails application. For example, you could use the daemons gem to generate a daemon script, give it full access to the Rails environment by including environment.rb, and then run it along with your Rails application. This will allow your daemon to have access to your application’s models, making integration a snap.

If you find that the people you need to communicate with don’t like AIM, you can use libpurpl, the library that powers Pidgin, a multiprotocol chat client. There is a Ruby gem named ruburple that hooks into libpurpl, but many people seem to experience sporadic success with building it. If you’re able to build it, it’s a great way to access a number of chat protocols easily. If that doesn’t work for you, you can also use XMPP and Jabber to access other chat protocols. We’ll talk about Jabber next.

6.2.2. Automating Jabber

Jabber is an open source IM platform. The great thing about Jabber is that you can have your own private Jabber server, which you can keep private or link with other Jabber servers. So, you can have your own private IM network or be part of the public Jabbersphere. In addition, XMPP (the Extensible Messaging and Presence Protocol that Jabber runs on) offers a nice set of security features (via SASL and TLS). XMPP servers can also bridge to other transports like AIM and Yahoo! IM. You can learn more about setting up and maintaining your own Jabber server from the Jabber website at http://www.jabber.org/.

Problem

You want your administrators to be able to manage MySQL via Jabber messages sent from your Ruby application.

Solution

Ruby has a number of Jabber libraries, but the most advanced and best maintained is xmpp4r. In this section, we’ll look at using a library built on top of xmpp4r named Jabber::Simple, which simplifies the development of Jabber clients in Ruby. You’ll need to install both gems (xmpp4r and xmpp4r-simple) to use these examples.

Jabber and Rails

If you’re interested in using Jabber with Rails, take a look at Action Messenger, which is a framework like Action Mailer but for IM rather than email. The Action Messenger home page is http://trypticon.org/software/actionmessenger/.

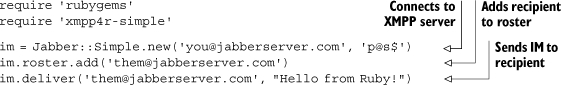

The process for interacting with Jabber is very similar to the process for interacting with AIM, but the API exposed in Jabber::Simple is slightly, well, simpler. Take a look at listing 6.8 for an example.

Listing 6.8. Building a simple Jabber::Simple object

First, we create a new Jabber::Simple object. When creating this object, you must provide your login credentials, and the account will be logged in. The new object is essentially an XMPP session with a nice API on top of it. The roster attribute provides an API to the logged-in account’s contact list, which allows you to add and remove people. Finally, we use the deliver method to send a message to the person we added to this account’s contact list.

Contact list authorization

When you add someone to an account’s contact list, the person being added will have to authorize the addition of her account to your contact list. You can use the subscript_requests method to authorize requests for adding your bot. See the Jabber::Simple documentation for more information.

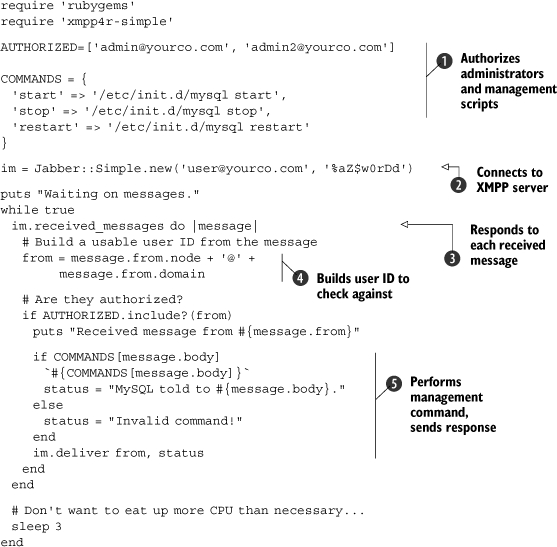

Jabber::Simple doesn’t implement anything akin to the callbacks in Net::TOC, but the mechanism for receiving messages is fairly straightforward. As an example, let’s say you wanted to expand on our earlier MySQL control service (from listing 6.4) to allow your administrators to stop, start, or restart the server over IM. Listing 6.9 shows one implementation of this script.

Listing 6.9. Managing MySQL via Jabber rather than email

We start off by defining a few constants ![]() : AUTHORIZED is an Array of Jabber users that we permit to issue commands, and COMMANDS is a Hash of command sequences we’ll use to control the MySQL server. Next, we create our Jabber::Simple object

: AUTHORIZED is an Array of Jabber users that we permit to issue commands, and COMMANDS is a Hash of command sequences we’ll use to control the MySQL server. Next, we create our Jabber::Simple object ![]() and call the received_messages method

and call the received_messages method ![]() . This method gives us an iterator that will yield each message received since the last received_messages call.

. This method gives us an iterator that will yield each message received since the last received_messages call.

Now we need to figure out who sent us the message. The message.from attribute is actually a Jabber::JID object that gives us access to some of the internal Jabber data. Earlier in the chapter, we used email to administer MySQL, and we had to worry about spoofing the sender’s address. XMPP uses server-to-server authentication to eliminate address spoofing, so we can trust the sender’s identity. Since we need to know only the username and domain, we extract that and build a usable string ![]() . Next, we check to see if the user who sent us the message (now in from) is authorized to be doing so, and if so, we try to issue the command

. Next, we check to see if the user who sent us the message (now in from) is authorized to be doing so, and if so, we try to issue the command ![]() . If they sent a bad command (i.e., not “start,” “stop,” or “restart”), we tell them so. Otherwise, we go to the next message or begin listening for new messages again.

. If they sent a bad command (i.e., not “start,” “stop,” or “restart”), we tell them so. Otherwise, we go to the next message or begin listening for new messages again.

Discussion

The Jabber::Simple library is nice, but if you like to get down to the bare metal, you could use xmpp4r directly. It offers a higher level API (not quite as high as Jabber::Simple, but tolerable), but it also gives you access to much of the underlying mechanics. This access could be useful if you’re building custom extensions to XMPP or you want to do some sort of filtering on the traffic.

6.3. Summary

We’ve taken a look at a few approaches to communication automation in this chapter. Email automation has been in use for years in certain arenas, but we are seeing it expand out into more business applications (some of which were discussed here) and into the consumer world (with things like Highrise from 37signals and Twitter). AIM bots have been around for years (Jeremy can remember writing one in 1997!), but they’re no longer exclusively in the territory of 13-year-olds and spammers—they’ve moved into the business-tool arena. Voice over IP (VOIP) seems to be moving in that same direction, with technologies like Asterisk and tools like Adhearsion.

All this is to say that we are beginning to see people use existing methods of communication in new and different ways. Fortunately, the Ruby community is constantly building new tools to work with these technologies, and many of them, like Adhearsion, are pioneers in their field. Another area where Ruby has pioneered is databases, where ActiveRecord and some of the new ORM libraries are pushing the boundaries of DSL usage in database programming.

Now that we have covered the use of email and instant messaging for automation, we’ll turn our attention to technologies designed specifically for exchanging messages between applications, and we’ll talk about asynchronous messaging using the open source ActiveMQ, big-iron WMQ, and Ruby’s own reliable-msg.