3. Lean-Agile Mindset

People are already doing their best. The problem is with the system. Only management can change the system. It is not enough that management commit themselves to quality and productivity, they must know what it is they must do. ... Such a responsibility cannot be delegated.

—W. Edwards Deming

Applying the Agile Manifesto at Scale

Overview

Deming’s quotes remind us of a basic premise of the Scaled Agile Framework (SAFe): The ultimate responsibility for the success of the enterprise, and thereby any significant change to the way of working, lies with management. And there’s no question that moving to a Lean-Agile paradigm will be a huge change. Not only are the practices different, but the belief system, core values, culture, and management philosophy are different as well.

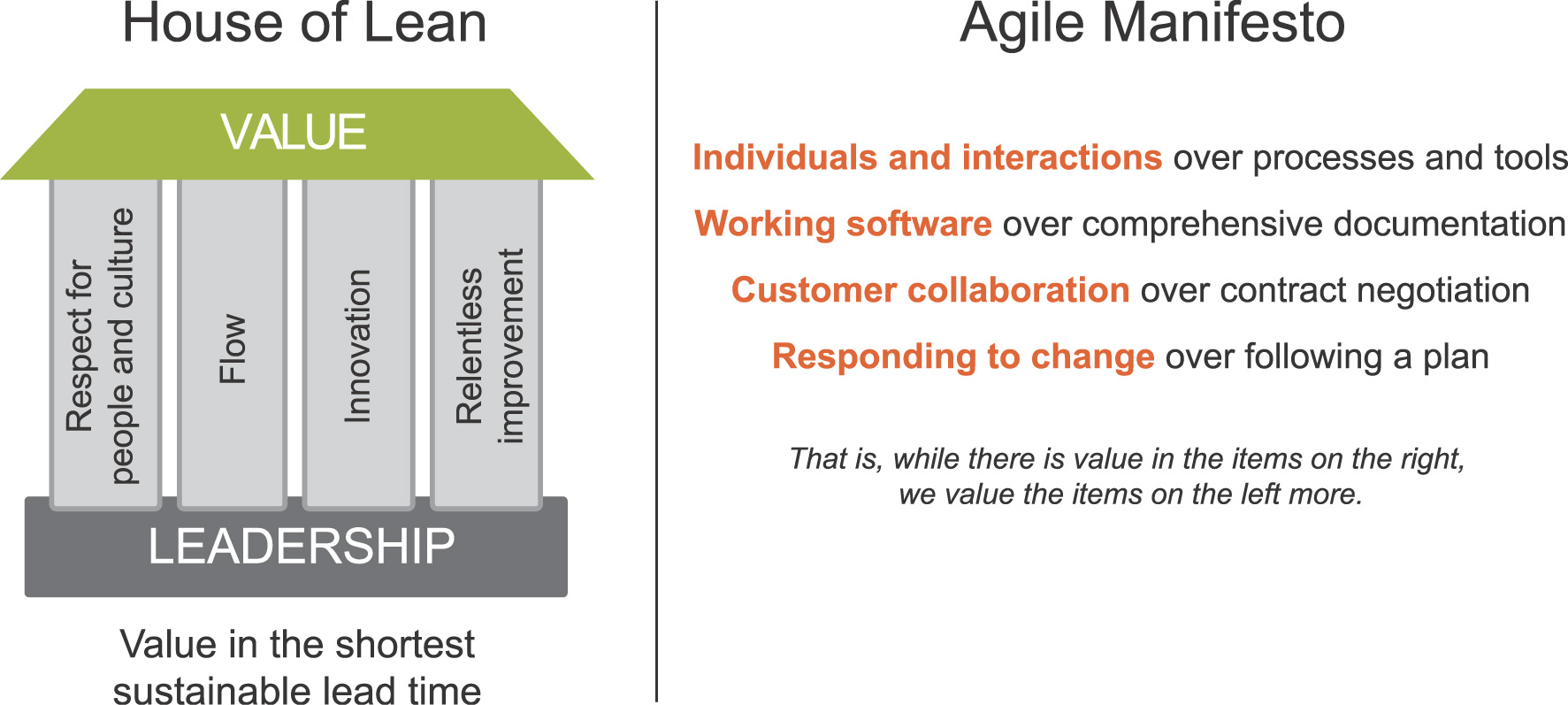

To begin this journey of change and instill new habits into the culture, leaders and managers should learn and adopt the Lean-Agile mindset, as shown in Figure 3-1.

There are two primary aspects of a Lean-Agile mindset, described here:

• Thinking Lean. Organized around six key concepts, much of the thinking is pictured in Figure 3-1. The roof represents the goal of delivering value. The pillars support this goal through the concepts of respect for people and culture, flow, innovation, and relentless improvement. Lean leadership provides the foundation on which everything else stands.

• Embracing agility. SAFe is built entirely on the skills, aptitude, and capabilities of Agile teams and their leaders. And while there’s no single definition of what an Agile method is, the manifesto provides a value system that introduced Agile methods into mainstream software development.

Together, these help create the Lean-Agile Mindset, which is a large part of a new management approach and an accelerator to cultural improvement. It provides the thinking tools and belief system that leadership needs to guide a successful enterprise transformation. In turn, this helps both individuals and businesses achieve their goals. Each is described further in the following sections.

Thinking Lean

While initially derived from Lean manufacturing,1 the principles and practices of Lean thinking as applied to software, product, and systems development are now deep and extensive. For example, Allen Ward,2 Don Reinertsen,3 Mary and Tom Poppendieck,4 Dean Leffingwell,5 and others have described aspects of the core principles and practices of Lean thinking using a product development context. In combination with these factors, we developed the SAFe House of Lean, inspired by the Toyota “House of Lean” and others.

1. James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel Roos, The Machine That Changed the World: The Story of Lean Production—Toyota’s Secret Weapon in the Global Car Wars That Is Revolutionizing World Industry (Free Press, 2007).

2. Allen Ward and Durward Sobek II, Lean Product and Process Development (Lean Enterprise Institute, 2014).

3. Donald G. Reinertsen, The Principles of Product Development Flow: Second Generation Lean Product Development (Celeritas, 2009).

4. Mary Poppendieck and Tom Poppendieck, Implementing Lean Software Development: From Concept to Cash (Addison-Wesley, 2006).

5. Dean Leffingwell, Agile Software Requirements: Lean Requirements Practices for Teams, Programs, and the Enterprise (Addison-Wesley, 2011).

Goal: Value

The roof of the house represents value. The goal is to deliver the maximum value in the shortest sustainable lead time, while providing the highest possible quality to customers and to society as a whole. High morale, emotional and physical safety, and customer delight are further goals with economic benefits.

Pillar 1: Respect for People and Culture

A Lean-Agile approach doesn’t implement itself or perform any real work. People do all the work. Respect for people and culture is a basic human need. People are empowered to evolve their own practices and improvements. Management challenges people to change and may help steer them toward improvement. However, the teams and individuals learn problem-solving and reflection skills and are accountable for making the appropriate improvements.

To evolve into a Lean organization, the culture will need to change substantially. For that to happen, the organization and its leaders must change first. And respect for people and culture should extend to relationships with suppliers, partners, customers, and the broader community. After all, they are key to the success of the enterprise.

When there is true urgency for change, improvements in culture will naturally occur. First, understand and implement SAFe values and principles. Second, deliver winning results. Changes to culture will surely follow.

Pillar 2: Flow

The key to successfully implementing SAFe is establishing a continuous flow of incremental value delivery based on continuous fast feedback and adjustment.

Continuous flow enables faster value delivery, effective built-in quality practices, constant improvement, and evidence-based governance.

The principles of flow are an important part of the Lean-Agile mindset. These include understanding the full value stream, visualizing and limiting Work in Process (WIP), and reducing batch sizes and managing queue lengths. Additionally, Lean focuses on reducing delays and eliminating waste, meaning activities that add no value.

Pillar 3: Innovation

Flow builds a solid foundation for the delivery of value. But without innovation, both the product and process will steadily decline. In support of innovation, Lean-Agile leaders must do the following:

• Understand and implement the Japanese concept of “Gemba.” It advises management to “get out of the office” and into the workplace. This is where value is actually produced and products are created and used. As Toyota’s Taiichi Ohno said, “No useful improvement was ever invented at a desk.”

• Provide a regular time and space for people to be creative. Time for innovation must be purposeful and become part of the natural development rhythm. SAFe’s Innovation and Planning (IP) iteration provides one such opportunity.

• Avoid the trap of focusing on the “tyranny of the urgent.” Innovation rarely occurs with 100 percent people utilization and constant firefighting.

• Apply innovation accounting.6 Establish nonfinancial, actionable metrics that provide fast feedback on the important elements of the solution’s new concepts, business model, and/or features.

6. Eric Ries, The Lean Startup: How Today’s Entrepreneurs Use Continuous Innovation to Create Radically Successful Businesses (Crown Business, 2011).

• Validate innovations with customers and then pivot without mercy or guilt when the hypothesis needs to change.

Pillar 4: Relentless Improvement

The fourth pillar is relentless improvement. It guides the business to become a learning organization through continuous reflection and adaptation. A constant sense of competitive danger drives it to aggressively pursue improvement opportunities. Leaders and teams systematically do the following:

• Optimize the whole organization and the development process, not just parts

• Consider facts carefully and then act quickly

• Apply Lean tools and techniques to determine the root cause of problems, and apply effective countermeasures quickly

• Reflect at key milestones to openly identify and address process shortcomings at all levels

Foundation: Leadership

The foundation of Lean is leadership, the key enabler for team success. The ultimate responsibility for the adoption and success of the Lean-Agile paradigm lies with the enterprise’s managers, leaders, and executives. To be successful, leaders must be trained in these new and innovative ways of thinking and exhibit the principles and behaviors of Lean-Agile leadership.

Embracing Agility

The right half of the Lean-Agile Mindset is, of course, Agile. In chapter 1, “Business Need for SAFe,” we introduced the Agile Manifesto. It provides the foundation for empowered cross-functional, self-organizing, self-managing teams. The rest of this chapter is devoted to it.

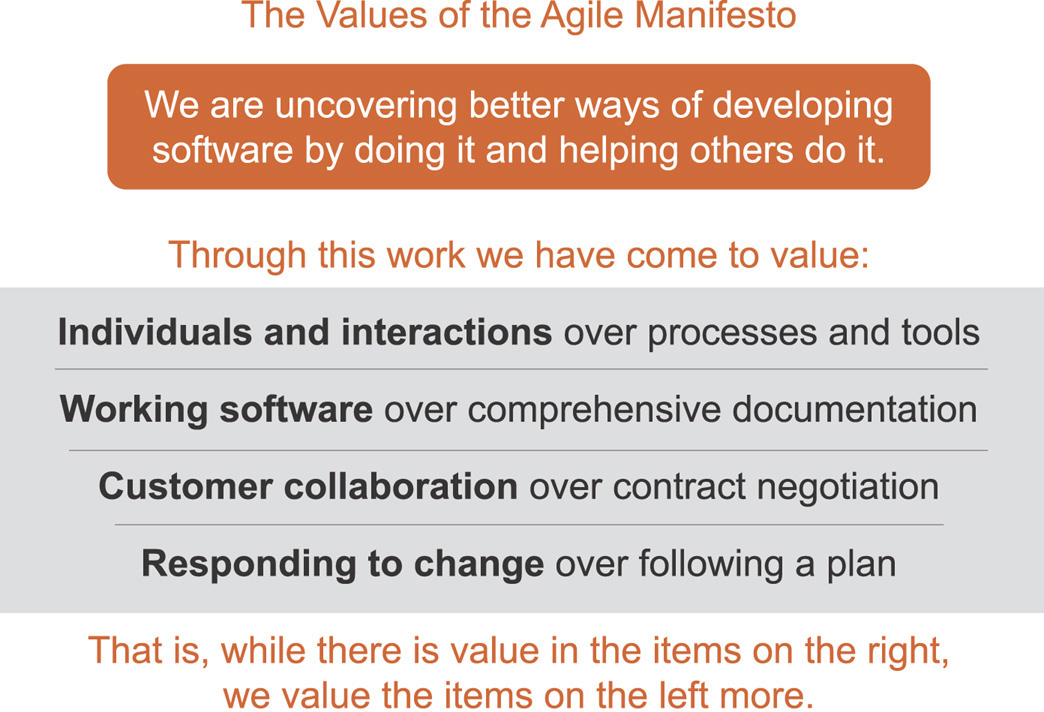

The Values of the Agile Manifesto

Figure 3-2 illustrates the Agile Manifesto and is followed by a description of its four values.

We Are Uncovering Better Ways

The first phrase of the manifesto deserves emphasis: “We are uncovering better ways of developing software by doing it and helping others do it.”

We interpret this phrase as an ongoing journey of discovery to increasingly embrace Agile behaviors, a journey that has no ending. SAFe is not a fixed, frozen-in-time framework. As soon as we uncover better ways of working, we adapt the framework, as evidenced by more than four major releases as of this writing.

Where We Find Value

We’ll discuss the values shortly, but the final phrase of the manifesto is important and sometimes overlooked: “That is, while there is value in the items on the right, we value the items on the left more.”

Some people may misinterpret the value statements as a decision between two choices (for example, working software versus comprehensive documentation). But that is not the intent. Both items have value; however, the item on the left has more value (for example, working software). The Agile Manifesto is a mantra for us not to be rigid or dogmatic in our approach but instead to embrace the need to balance the values depending on the context.

Individuals and Interactions over Processes and Tools

People build software and systems, and that requires teams to work together effectively. Processes and tools are important, but they do not replace individuals and interactions.

With respect to process, Deming notes, “If you can’t describe what you are doing as a process, then you don’t know what you are doing.” So, Agile processes in frameworks like Scrum, kanban, and SAFe do matter. However, a process is only a means to an end. When we’re captive to a process that isn’t working, you may know “what you’re doing,” but “what you’re doing may not be working.” So, favor individuals and interactions and then modify processes accordingly.

In a distributed environment, tools are critically important to assist with communication and collaboration (for example, video conferencing, instant messaging, ALM7 tools, wikis), especially at scale. However, tools should not be used as a substitute for regular, face-to-face communication.

7. Application Lifecycle Management

Working Software over Comprehensive Documentation

Documentation is important and can provide great value (for example, user help, models, story mapping, regulatory/compliance documentation). However, creating documents for the sake of complying with outdated corporate governance models does not provide value. As part of a change program, governance needs to be updated to reflect the Lean-Agile way of working.

Software requirements specifications are tricky, and one could assume that the authors of the manifesto were particularly concerned about them. Too often, they cause Big Design Up Front (BDUF) and project delays consistent with waterfall thinking. They frequently constrain development to overly detailed written specs that are not always practical (or desirable) to implement. Moreover, people usually do not know what they want until they see it working in action.

Therefore, it’s more valuable to show your customer working software and get fast feedback, rather than create comprehensive documentation (especially the wrong kind) too early in the process. The goal of software development, after all, is to create innovative solutions, not a library of documents. Therefore, favor working software. Document only what’s necessary.

Customer Collaboration over Contract Negotiation

Customers are the ultimate deciders of value. Determining value requires close collaboration on a daily basis. Contracts are often necessary for communicating and agreeing on the rights, responsibilities, and economic concerns of each party. But all too often, contracts over-regulate what is to be done and how to do it. No matter how well they’re written, contracts are not a replacement for regular communication, collaboration, and trust. Contracts should be written to be win-win propositions. Win-lose contracts usually result in poor economic outcomes and distrust, creating short-term relationships instead of long-term business partnerships. Favor customer collaboration.

Responding to Change over Following a Plan

Change is a natural part of software and systems development, a reality that must be reflected in the process. The strength of Lean-Agile development is in how it embraces change. The process of product development is about converting uncertainty to knowledge. As the system evolves, so does the understanding of the problem and solution domain. Business stakeholder understanding also improves over time, and customer needs evolve as well. Indeed, this variability adds value to our system.

Of course, the phrase “over following a plan” means that there actually is a plan. Planning is an important part of Agile development. Indeed, Agile teams and programs plan more often and more continuously than teams using a waterfall process. However, plans must be adaptable as new learning occurs, new information becomes visible, and the situation changes. Worse, measuring conformance to a plan drives the wrong behaviors (following the plan over empiricism) and should be avoided.

Agile Manifesto Principles

The manifesto has 12 principles that support its values. Listed here, the principles take the values one step further and describe more specifically what it means to be Agile:

1. Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

2. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

3. Working software is the primary measure of progress.

4. Deliver working software frequently within a couple of weeks to a couple of months, preferring a shorter timeline.

5. Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

6. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

7. The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

8. Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

9. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

10. Simplicity—the art of maximizing the amount of work not done—is essential.

11. The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

12. At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, and then fine-tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

Most of these are self-explanatory, so no further elaboration is needed, except for a discussion of applying the Agile Manifesto at scale, covered next.

This combination of values and principles in the manifesto creates a framework for what the Snowbird attendees believed to be the essence of Agile. The industry is the recipient of the extraordinary business and personal benefits of this new way of thinking and working. We are grateful.

Applying the Agile Manifesto at Scale

The brief document that launched this industry movement is more than 15 years old. Since then, not a word has been changed. It’s legitimate to ask, given all the advancements in the last 15 years, whether or not the manifesto is still relevant. Or should it be treated like a historical document that has served its purpose?

Moreover, it was defined for small, potentially fast-moving software-only teams, raising another legitimate question: Does the manifesto scale to the needs of enterprises developing the biggest and most complex software and systems? Does it serve those that require hundreds of people to build and have unacceptably high costs of failure? Although the manifesto might not have been designed for them, can it be applied?

Rather than judge these questions on our own, what better way to assess its practicality than by asking those who are actively engaged in building these new systems? Specifically, we ask SAFe students to do the following exercise in class, as described in Figure 3-3.

The typical response is principles 1, 3, 4, 7, 9, and 12 “work as-is.” The conclusion is that most Agile principles scale without requiring any rethinking for scale. The other principles typically need some further discussion, as highlighted here:

• Principle #2—Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage. The answer here is largely “it just depends.” This isn’t an attitude problem on the part of the class participants. Rather, it’s a practical recognition that the cost of change for some types of late modifications may create a situation that is not feasible. (For example, can we change the optical resolution of a geophysical satellite a few months before launch?) And yet, if it’s a software-only change and the program can still meet any compliance and validation criteria and launch on time, then of course we want to make that change.

• Principle #5—Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project. For this concept, the spirit is certainly willing. However, there are limitations regarding the economic practicality and convenience of daily onsite feedback from customers of large programs. But we fully respect the sentiment. SAFe addresses this need through certain roles, such as the Product Manager and System Architect/Engineer. We also engage the customer directly at system and solution demos and other points throughout the development process.

• Principle #6—The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation. Attendees always agree with the intent of this principle. And SAFe largely addresses it with periodic face-to-face PI planning events. This probably addresses the majority of needs for efficient communication. However, if you needed a supplier to build a smart power device to fit the physical and thermal constraints of your satellite, you would indeed want to speak to them continuously. In addition, you will certainly want to document the results of those decisions. Fortunately, “working software over comprehensive documentation” does not mean “instead of.” So, most serious Agilists proceed with knowledge of the intent, as well as the practical limitations of that principle.

• Principle #11—The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams. Nearly everyone agrees with this principle, depending on how you define a team and how you define the subject and scope of the decisions. All agree that local decisions are generally best. After all, that’s part of SAFe principle #9—decentralize decision-making. However, that principle also provides the economic rationale for when some decisions are most efficient when they’re centralized.

Principle #11 may be the tricky one, and yet it clearly is the essence of Agile. Let’s test it with a scenario. For example, let’s discuss the User Interface (UI) design for a significant software application, a system where many teams are implementing numerous elements.

• If each team made their own local decisions, they would be unlikely to produce a design that supported the significant cross-cutting usage scenarios that they may not even be able to envision. The functions may work, but the usability of the solution may frustrate the customer. For that we’d need a centralized view, which if not created by the teams, would need to be imposed on them. And yet, the role of a User Experience (UX) lead is clearly articulated as an Agile Release Train (ART) role in SAFe. In that case, the best requirements and designs do emerge from the ART team. But, again, it does depend on how you define the team.

• In the larger view, decisions as to how the UI would work across multiple platforms in a large value stream may go beyond the limits of ART level design. Those judgment calls may need to occur at a higher level.

The conclusion from this exercise is that the Agile Manifesto does indeed scale, even though some principles require a somewhat expanded perspective. It remains as relevant today as it was when it was written. We’re fortunate to have it, and it plays a vital role in SAFe.

Summary

This chapter gave an overview of the Lean-Agile mindset, which is critical for supporting Lean-Agile development at scale across the entire enterprise.

The key takeaways from this chapter are as follows:

• The ultimate responsibility for the success of the enterprise, and thereby any significant change to the way of working, lies with management.

• To begin the Lean-Agile journey of change and instill new habits into the culture, leaders and managers should adopt the mindset, principles, and values provided in SAFe’s House of Lean and Agile Manifesto.

• The SAFe House of Lean consists of the following elements:

1. Goal (the roof): Value

2. Pillar 1: Respect for People and Culture

3. Pillar 2: Flow

4. Pillar 3: Innovation

5. Pillar 4: Relentless Improvement

6. Foundation: Leadership

• The Manifesto for Agile Software Development has four simple values and twelve principles that define what it means to be Agile, and it is often referred to as the Agile Manifesto.

• The Agile Manifesto does indeed scale, even though some principles require a somewhat expanded perspective.