CHAPTER TWENTY

Photography Becomes Digital Imaging

PHOTOGRAPHY AS PIXELS: FROM SILVER HALIDE TO SILICON

The revolution brought about by the near-universal adoption of digital technologies has transformed society, and its effect on photography was unprecedented. Prior to this time, photography seemed solid, reliable. If you bought a Nikon or Hasselblad camera, you thought you would use it for the rest of your life. Everyone took pictures— but only artists or those trained in the mechanics of photography made images that were seen by hundreds or thousands of people. But there was a storm brewing deep in the heart of computer code that would radically alter photography forever.

We have become used to a world where rapid change is the norm, with information and images instantly accessible. Those who have grown up since the late 1990s when the Internet became a household word may not fully grasp the degree of transformation that has taken place and how for many, the advent of digital imaging felt like an attack on all that photographers held as sacred: the physical connection between the subject being photographed and the resulting imagery. Plus, the camera itself moved from being a picturemaking machine to a data-collection tool whose results are an expressive fusion of pixels directed over time and space by the photographer or/ and by the camera itself.

Perhaps more than any other art form, photography has undergone a continual technical evolution. As in most groundbreaking situations, change begins slowly and then, especially with technology, accelerates exponentially following Moore’s Law1 In the 1980s, digital imagemaking tools were expensive and uncommon, requiring access to powerful institutional computers and proprietary software to explore this new imagemaking frontier. At the start of the 1990s, digital imaging was still in its infancy and was as much a novelty as a useful tool set, with only the affluent and adventurous being able to work digitally. Had things stopped there, digital photography would exist as simply another alternative process. But in a one-decade period, beginning in the late 1990s, every photographic tool and technology, with the exception of the lens, was overthrown by the digital revolution.2 Some, such as art critic Peter Plagens,felt that digital photography was such a “megaquantum leap”3 that it warranted a completely new name. Entire industries and companies rose and fell as the essential structure of photography underwent a radical transformation. Eastman Kodak became the poster child of a large corporation unable to make the transition to digital, eventually leading to its bankruptcy4 These events occurred so rapidly that there was seldom time to absorb their meaning. It is only now, with distance, that we are able to grasp some of the ramifications of these changes.

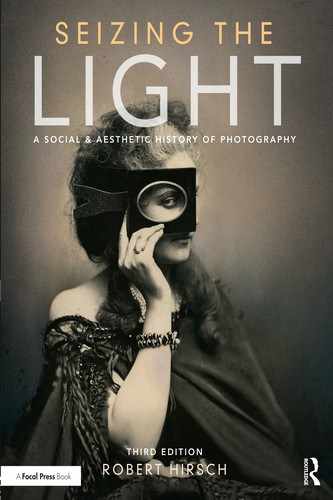

© NANCY BURSON. Mankind, 1983–85. 7¾ × 7½ inches. Gelatin silver print.

Photography’s fundamental concept had been about formulating physical changes to tangible materials in response to light. Like a bullet hole in a wall, a photograph is evidence of a concrete occurrence.5 Digital images, formed of pixels encoded as strings of binary numbers, breaks this customary prescription by removing the materiality from the process.6 Since Talbot made public his negative/positive process, photographs have been about reproducing outer reality with Renaissance-like perspective depictions. Digital technology dispenses with this cherished notion by taking reproduction into the realm of disembodied or dematerialized ideas. For instance, with a physical object like a photographic negative, only one person at a time can work with it. With information, be it an idea, a secret, or a digital image file, once it is shared it becomes the equal property of many and subject to their multiple treatments and interpretations. In digital imaging the concept of an original loses it meaning because the master image can be exactly and endlessly duplicated without the physical degradation that accompanies reproducing physical materials. As we have read, photographs have been altered since their inception, but not with the seamlessness and ease that digital imaging programs like the now ubiquitous Adobe Photoshop and similar programs make possible.

Nancy Burson (b. 1948) was one of the first to utilize computer power to alter and challenge cultural concepts of race. In Mankind (1983—85) she applied digital morphing technology to create images of people who had never existed, such as a composite person made up of African, Asian, and Caucasian features weighted according to current population statistics. Such pictures have no original physical being and exist only as digital data, showing us how images can be more about intangible ideas than external subjects. These images emblematize a media-based society where the image (the perception of reality) is more important than reality itself. Burson has also used these tools to age-enhance human faces, allowing law enforcement officials to locate missing children and adults. Her Human Race Machine encourages people to view themselves as a different race, allowing us to see that race is not a genetically but a socially based concept. Like a scientist, Burson makes explicit the gap between statistical data and the world as we experience it.

PHOTOGRAPHY’S SOCIAL CONTRACT WITH TRUTH

We have a social contract with photographs and their truthfulness, which is why we still accept them as valid symbols of ourselves on official documents such as driver’s licenses and passports. In the past, philosophers like Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) devised categorical imperatives, which acted as preconditions for forecasting the ultimate reality—the causes and principles that make up much of Western thinking. Now, and perhaps especially since photography’s invention, images replace text and define behavior, shape identities, set fashions, and permeate our memories. Photo-based images are so interwoven into daily existence that life has become a collection of images, generating confusion between the artificial and the real.7 As a result, entertainment and mass media provide the primary frames of reference through which we filter our experiences. So-called “reality” based television shows, such as Survivor, American Idol, Dancing with the Stars, and Duck Dynasty, graphically demonstrate how the authority of images frames realism, blurring the borders between truth and illusion, and news and entertainment. As a result, today’s digital culture has rendered only the most banal of photographs as above suspicion while remarkable images have often been trivialized as fleeting spectacles.

Digitization gives new meaning to Kant’s belief that we should behave as if the maxims on which we act and define society become, through our will, universal laws. The malleability of digital media converts the static into the dynamic, turning completed, unalterable ideas and works into things of the past by permitting the process to be part of the product. Professions like photojournalism, rooted in the authenticity of photographic appearance and in their circulation via the halftone reproduction process, have been radically affected by the digital age (see Chapter 14). As old journalism models fail, news organizations have drastically cut staff photographers, relying instead on untrained “citizen journalists” and social media to cover stories to save money, best the competition, and for advertising and propaganda purposes. Unfortunately, this has led to numerous incidents of inaccurate and fraudulent use of images, as in the BBC coverage of Israeli/Gaza war of 2014.8 As the venerable adage proclaims: “The camera does not lie, but photographers do.”

Digital cameras record far more information than just the frame numbers and the sequence of exposures as in film cameras. Metadata, additional information embedded in a digital image file, stores the exposure information of f/stop, shutter speed, the date, time, and increasingly the location where the exposure was made through GPS data. However, like all digital information, those with some technological savvy can alter or remove it. Even so, such data can become evidence to law enforcement, divorce lawyers, and news organizations among others. Since the storage media in electronic cameras can be erased and reused, a busy photojournalist might delete images of an event before their publication. With the deletion of the master captures, a complete record of context is lost. If any of the remaining photographs were altered before publication, there would be no root image for comparison to prove that changes had been made.

Confidence in the accuracy of photographs has eroded as news providers modify photographs without informing their readers. Often, the fault lies not with the photographers, but with the editors who control the content and style of their publications. Although media photographs have been altered since the invention of the printed halftone, the current descent can be traced back to 1982 when National Geographies editors “moved” the Egyptian Great Pyramids at Giza closer together to accommodate the vertical composition of their cover. On the other side of the editorial desk, unethical photojournalists have lost their jobs because they were caught “Photoshopping” images before transmitting them to their editors.9 The intentional mishandling of such undetectable changes has contributed to skepticism about the accuracy of all photographs. As a result, the public is increasingly aware of the impossibility of separating “legitimate” images from those that have been manipulated without explanation, and we all may come to regard news pictures as little more than advertisements, illustrations, and/or propaganda. Advertising has a long tradition of retouched images and today there is a widely unquestioned expectation that images for marketing have been significantly altered. In any case, the photojournalistic mode of direct camera representation, as seen in most major news media outlets, continues to play a vital role in how we assess the world.

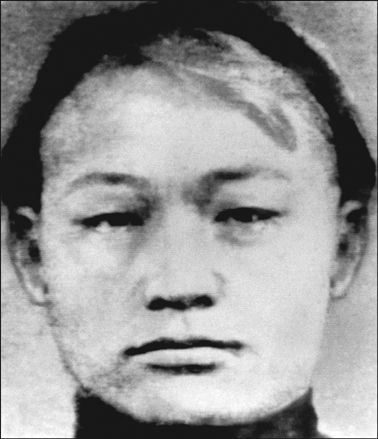

Barry Frydlender’s (b. 1954) images, which tackle the political, religious, and social complexities of life in Israel, indicate how digital imaging has altered the definition of photographic truth by mimicking and therefore undermining traditional photojournalistic methods. Although images, such as Last Peace Demonstration (2004), appear to be a seamless representation of an actual event, they actually show the antithesis of single exposure “ straight” photography. Such a picture results from numerous images that Fry-dlender assembled into a single, time-compressed cinemascopic frame. As such, he delivers a synthesis of the event based on many different vantage points and moments in time. “It’s not one instant, it’s many instants put together, and there’s a hidden history in every image.”10 This methodology results in an imagemaker who no longer passively experiences and edits the world, but is an active participant who creates a realm and then photographically enlivens it.

The increasingly global adoption of all things digital is part of a larger questioning of the meaning of truth, which leaves the interpretation of cultural history, political events, and even personal memories more ambiguous, changeable, and unreliable than ever. The topic of an ever-shifting authenticity has received much cultural attention on television, particularly by political satirist Stephen Colbert, who popularized such buzz-words as “truthiness,”11 meaning “truth unencumbered by the facts,” and “Wikiality” derived from the open-source Wikipedia information website, and meaning “reality as determined by majority vote.”12 It references Wiki websites where anything can become “true” if enough people say it is. Colbert proved the point by regularly calling on his audience to make changes to Wiki sites based on his false assertions.

By inference, any kind of digital information— including audio and moving images—can become “real.” This means that digital truthiness, truth without the authority of the original, can be used to visualize playful fantasies or dangerous fallacies. Since people like to “improve” upon the past, the ubiquity of digital practice raises questions about how these new abilities might change the future and affect our cultural and private memories: Will we in our technical sophistication delete people and events that fall out of favor as has been done under totalitarian regimes?13 Will we convincingly rewrite a memory to alter the outcome of an event or exaggerate our strengths and play down our weaknesses?14

© BARRY FRYDLENDER. Last Peace Demonstration, 2004. 50 × 6 feet 6% inches. Chromogenic color print.

COURTESY Andrea Meislin Gallery, New York.

Ultimately, the meaning of photographs depends on what viewers decide to believe about them. By disputing the medium’s claims of objectivity through the use of photographic strategies that embrace artifice and simulation, conceptual and postmodern artists anticipated the digital message that photographs are not neutral containers of reality. Digital imaging tools make it possible to easily improvise or subvert reality. This has spawned artists who invent worlds based on the sensation and emotional weight of a subject rather than finding and presenting them, and viewers who are willing to accept such inventions. Into the first decades of the twenty-first century, artists have taken advantage of this multifaceted ability to express what makes up the “truth” of our world, and the signs that once were meant to refer to reality now only point to individualized versions of that reality.

Gregory Crewdson (b. 1962) applies elaborate Hollywood production methods, involving entire crews of technicians, to stage condensed cinematic stills that explore the tension between domesticity and nature in isolated suburban life, often with a surreal Freudian twist (his father was a psychoanalyst and he would listen through the floorboards to the patients in his father’s office in their Brooklyn home).15 Likewise, his organizational working process, involving preproduction, production, and postproduction, often expresses a similar sense of removal, isolation, and solitude. As an artist and teacher, Crewdson has propagated the use of intricate theatrical staging and lighting with digital manipulation to fabricate self-enclosed scenes that resemble museum dioramas and impart a sense of voyeurism, as if by an omnipotent observer, illustrating the malleability of photographic information in the digital age.16 In any case, the primary issue remains not how an image is made, but what it communicates. Photographs continue to astonish viewers because so many do succeed in conveying meaning, regardless of whether or not they are unfailing containers of an agreed-upon reality.

© GREGORY CREWDSON. Untitled, 2005. 64 ¼ × 95¼ inches. Chromogenic color print.

COURTESY Gagosian Gallery, New York

MEMORY IS FRAGILE

Arguably, photographs are our most emotionally loaded link to the past. Although most theorists agree that digital data can be exactly copied without loss, except when “glitches” occur, the problem of permanence remains an issue. Memory, for both humans and computers, is a fragile thing, always subject to alteration and deterioration. While digital storage capacity has increased and prices have plummeted, digital’s longevity has not made significant advancements in decades. Anyone who has worked with computers has experienced the frustration and expense of data loss.

All material things are ultimately vulnerable. Untold glass plates, negatives, and prints have vanished. Social media has replaced the family album, once the physical record of generations and the emotional treasury of precious images. Conversely, a check on eBay reveals that innumerable, tangible photographic prints have survived. In the past, significant bodies of photographs, such as those made by Mike Disfarmer (see Chapter 10), have only been posthumously brought to public attention when a large trove of works was rediscovered. While images continue to be made at a furious pace, their accessibility and permanence could be in doubt. Many people now put their trust in the Cloud, hoping that it will not evaporate and take all their images with it. Depending on circumstances beyond the control of most if not all photographers, we may be entering a time when a significant portion of our photographic heritage could be suddenly lost or locked away by obsolete programs in failed and/or discarded hard drives—little metal boxes as inaccessible as any vault.

MIRROR WITHOUT A MEMORY

In the June 1859 issue of The Atlantic Monthly, physician and poet Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote an article on “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph”17 describing photography as the mirror with a memory. He considered it a miracle of its age, and like all miracles, they display our deepest hopes and wishes. With the nearly universal acceptance of digital images, we are currently faced with an inversion of that phrase: the memory without a mirror, as we are now seeing a constantly changing stream of images on large and small screens. These images reflect both our outside world and our inner lives—and perhaps this has always been true about photography. However, we are now left to sort out which is which, as we quickly attempt to make sense out of images that are bombarding us faster than ever before.

Perhaps the greatest paradox is that with all of these technological changes, photography still remains recognizable as photography. When an artist, such as Sebastiào Salgado (see Chapter 14), switches from film to pixels his working style continues to be unmistakably his own. Just as the calotype added multiplicity and manipulation to the vocabulary of photography that the daguerreotype did not possess (see Chapters 2 and 3), digital tools have not eliminated the power of lens-based images, rather they have added to the possibilities. And while the darkroom mystery of making photographs has disappeared, cellphone cameras have vastly democratized the picturemaking process in localities, such as in Africa and China, where cameras were once not common. George Eastman’s 1888 dream for his Kodak #1 of making photography fun and easy to do (“You Press the Button, and We Do the Rest”) has been realized and extended, except now “you” can also do the rest.

The near universal appeal of photography may lie in its ability to share an experience. Digital technology has transformed the private, physical snapshot and the family album into public, virtual, social media events. In 1992 Kodak introduced its Photo CD service that was billed as the perfect archival solution. One hundred images could be scanned onto special gold discs designed to last a hundred years, but they were saved in a software format that has become unreadable by today’s computers. This was followed by JPEG files saved to the lower resolution Kodak Picture CD, which “gives you everything you need: your full roll of pictures, organized and safely stored, plus fun interactive software [that] makes it easy to email a picture, even share a whole roll with family and friends around the world and [the Kodak Picture Disk] lets you view your pictures on screen and more.”18 Now numerous such social media services, including Facebook, Flickr, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube, solicit people to post and view endless amounts of visual information, affecting society by making the once intimate and private snapshot public. How influential is photo-based social media? It has been reported that parents are now naming their children after Instagram photographic filters.19 However, a problem with many of the social media images is they are often not individually impactful, as they need to be seen within the wider context of the maker’s other posts to be comprehended, requiring one to scroll through virtual pages of personal vanity where daily banality is given with the importance of breaking news.

The marketing of digital image manipulation programs like Adobe Photoshop, released in 1990, coupled with constantly evolving delivery formats including the Internet, have given digital photographers cheaper, easier, faster, and more reliable methods of creating and distributing their work. While limitations of scale, resolution, and color calibration continue to be issues in the presentation of digital content, projectors and screens offer tonal ranges that significantly exceed that of prints with options such as tablets growing rapidly in popularity.

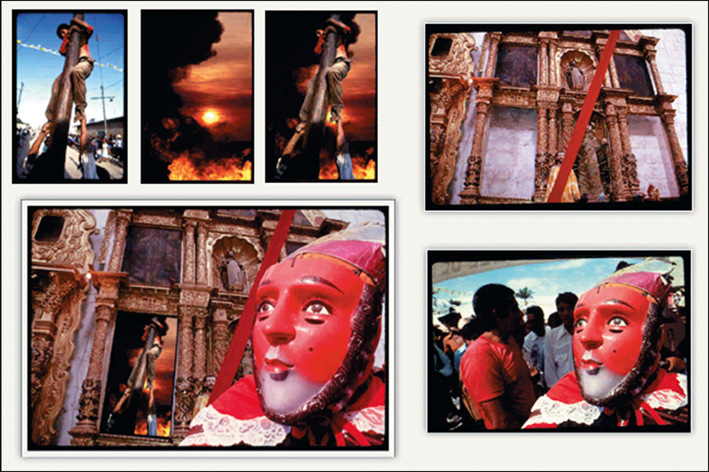

© PEDRO MEYER. Truths & Fiction: A Journey from Documentary to Digital Photography, 1995. CD-ROM.

This screen grab shows the original images Meyer used to digitally fashion his final representation. In the introduction to the print version of Truths & Fiction, Joan Fontcuberta stated: “Today more than ever the artists should reestablish the role of a demiurge and sow doubts, destroy certainties, annihilate convictions so that, at the other end of confusion, a new sense and sensibility can be created.”

In his bilingual CD, Truths & Fiction: A Journey from Documentary to Digital Photography (1995), Pedro Meyer (b. 1935) was one of the first photographers to take advantage of these new ways of working to explore how such shifts in visual truth can alter our relationship to photographic representation. By combining images, video, and narration, Meyer asks: “What should we expect or trust from an image during this time of transition between the analog and digital eras?” Meyer challenges assumptions about where photographic “truth” ends and “fiction” begins. In the “Digital Studio” section of his CD, Meyer takes viewers through the process of making completed images. The “Correspondence” section contains a discussion by people from various countries about the aesthetic and cultural ramifications of working digitally and the struggle with the uncertain nature of the photographic image. His website, www.zonezero.com, is dedicated to an ongoing reflection on the evolution of photography, and he presents a wide array of articles and work from around the world.

© ANDREAS GURSKY. 99 Cent, 1999. 81½ × 132⅝ inches. Chromogenic color print.

© Andreas Gursky/2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

COURTESY Sprüth Magers Berlin and London.

A key element of postmodern discourse can be understood in terms of photography’s relinquishing its role as society’s authoritative chronicler, in favor of a position that acknowledges that reality is a constantly evolving construction of our culture. As we have learned, Baudrillard rejects Oliver Wendell Holmes’s view of photography as a “mirror with a memory,” seeing it instead as an endless passageway of mirrors. The photo-based arts, including film, television, and video, serve as cultural agents that provide representational images that our society sanctions as a simulacrum of the real.20 The decline in the documentary authority of photography has much to do with Western culture, where a postmodern academic dissection of images has led to a devaluation of a photograph’s inherent believability Two important questions facing the photographic arts are: Can the digital replica, the twin that offers comforting fellowship at the expense of individuality, escape the aura of the original and provide insight into reality? And can this escape be affected by making a reproduction that is not only trustworthy, but also at times even “better” than the original?

In the high-end art world, Andreas Gursky’s (b. 1955) gigantic spectacles of industrial culture combine large-format film capture with imaging software to generate a premeditated hybrid of modern culture that appears more real than reality itself. His seductively colorful, super-formalistic, and hyper-detailed compositions synthesize the fast-paced, high-tech, and expensive phenomena of globalization. A student of the Bechers (see Chapter 18), he creates work that evokes an anonymous postmodern sense of indifference that can make individuals aware they are inconsequential, just one among billions. His images are so perfectly beautiful and sublime that they hang in both museums and corporate boardrooms. Gursky’s supersized prints, based on an art world language that confuses scale for importance, are indicative of the rise of market-driven production values. High-end, New York Chelsea galleries encourage artists to produce monumental works that successfully compete for wall space once reserved for paintings. Such works generate astronomical prices, making them investment opportunities. This has led some to say money is the new art criticism, and that it has replaced serious curatorship in deciding what major museums exhibit and ignores wide areas of artistic production.21

Rising from the desert and appearing as if it were a tangible work of digital photography, the massive Las Vegas casino complex New York, New York (1997), is a matchless example of amalgamated architectural playacting. Here the surrogate is not only acceptable but for many becomes a preferred way of visiting New York, one that eliminates the perceived hassles and risks of a trip to the actual city22 This reflects the postmodern mind that believes reality doesn’t exist until the viewer analyzes it. Another important question is: Does digitization inspire a metaphysical meditation about the one (the original) and the many (the copies), about reality and appearance? By accepting the duality of the twin, one can acknowledge the creative dilemma between the original and what it needs to be securely anchored to: the distance and separation of the copy. Like presenting one’s self to its reflection in a mirror, the quest for authenticity inevitably involves a doubling back, so that ultimately it takes a multiplicity of views to know the single one. This has lead the Marxist ideology of Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay,”The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (see Chapter 14), to be reworked for our modern capitalistic society where the existing system of valuing images based on their aura of originality has been replaced by one that prizes reproduction and mass circulation. Digital copying, file sharing, and website hits boost an image’s currency and make it more widely known and hence more valuable. This provides the copy with an importance not available to the original: the sense of being part of an extended collective experience.

In this vein, which reveals the contradictions and inconsistencies of what constitutes our contemporary reality, Thomas Demand (b. 1964), who originally trained as a sculptor, breaks down this facade by remaking the world with paper and cardboard sculptures that he then photographs. His facsimiles, sometimes based on historic photographs, that can range from Hitler’s underground bunker to Jackson Pollock’s Long Island studio, are destroyed after he photographs them. His conceptual methodology of structural instability, the final work being three times removed from the original, questions the relationship between the artificial and the real as well as between evanescence and permanence. “Sculpture aims for permanence, for presence, while the photograph is destined to render something visible that occurred at a particular moment in front of the lens. Essentially I play these two forms off against each other.”23 By working in this uncanny gap between the world and the images of the world, Demand punctures photographic veracity to fabricate an unstable world of images, eroding the idea of the maker-narrator as the trustworthy purveyor of a reliable record, which allows meaning to flow like running water.

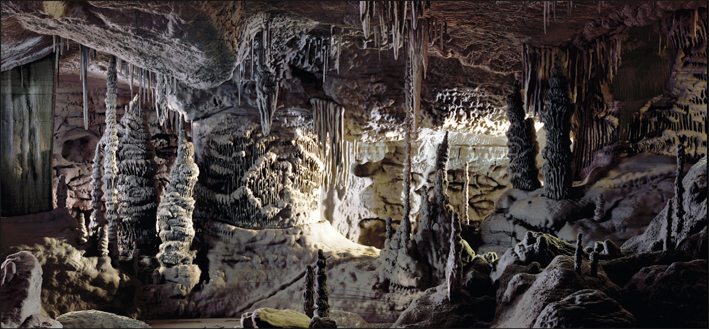

© THOMAS DEMAND. Grotte, 2006. 78 × 173 inches. Chromogenic color print.

For Grotte Demand used a digital program to cut each of the 900,000 layers of heavy gray cardboard, weighing 50 tons, which he used to build his grotto, layer upon layer. Wanting certain parts of the final photograph to lack definition, Demand actually built “pixels” in cardboard, tiny squares that deceive the eye into thinking the photograph is unfocused, when in fact it is faithfully reproducing the “reality” of the sculpted grotto. “Digital is just a technique of the imagination. It is opening possibilities that wouldn’t have been there before. But I lose interest in a photograph once I see it is digitally made because it is all about betraying you in a way. I think my work has a lot in common with what digital wants, rather than being digital. Basically, it is constructing a reality for the surface of a picture.”24

© 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, NY/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

INTERNET IMMEDIACY: SOCIAL MEDIA AND SMARTPHONES

In many ways, the social upheavals surrounding photography have had a bigger effect on imagemaking than the change of tools has had. The speed in which electronic media has so thoroughly enmeshed itself in Western culture has made analog photography nearly obsolete except as a fine art form. The ever-present accessibility of digital information has produced an expectation for immediacy where everything is anticipated to be available with a few clicks or taps. This expectancy has unsettled many people, leaving them nostalgic for the physical artifacts of the mechanical era. While digital has perhaps cut the phenomenological connection with the object being photographed that defined how we once knew the medium, one only has to look at the Web to see that all images are founded on a shared and evolving vocabulary. Certain artists have responded to this phenomenon by continuing to value thoughtful, methodical practices that allow time to ponder meanings and create works which reward contemplation. However, for the general public with its short attention span and scant knowledge of photographic history or practice, a quick stylistic simulation of a Polaroid or sepia tone from their camera phone applications usually satisfies such a contemplative urge. The downside of making everyone a photographer is there is often nothing special about such photographs because they are no different than millions of other pictures.25 Is there any limit to how many cat videos the world wants to see? Apparently not, as people constantly keep making and posting them on social media.26

© PENELOPE UMBRICO. Mountains, Moving: of Aperture’s Masters of Photography (22 Westons), 2014. Each being 6x8 inches, 8x8 inches, or 8 × 10 inches, overall 35 × 50 inches. Inkjet prints.

Penelope Umbrico informs us that her project Mountains, Moving, “considers an analog history of photography within the digital torrent that is its current technological manifestation. I steady my focus on the mountain: oldest subject, stable object, singular, immovable landmark, site of orientation, place of spiritual contemplation. My mountains are unstable, mobile, have no gravity, change with each iteration, remastered. I present a dialogue between distance and proximity, limited and unlimited, the singular and the multiple, the fixed and the moving, the master and the copy. I propose an inverse correlation between the number of photographs that exist of mountains at any one time, and the stability of photography at that time.”

COURTESY Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York, NY and Mark Moore Gallery, Culver City, CA.

The wildfire adoption of the smartphone camera has driven this change, making every user a potential photographer with the ability to integrate/share their images with just a tap on their phone’s keypad. This posting of digital images on social media sites has exponentially increased the number of accessible images in the world and the ease with which they can be appropriated and given new life in often-unexpected ways. Penelope Umbrico (b. 1957) explores the mounting production and consumption of online photographie images by examining subjects that are collectively photographed and posted “online as a collective archive that represents us—a constantly changing auto-portrait…. The work is an accumulation that navigates between consumer and producer, materiality and immateriality and individual and collective expression.”27 In her 5,377,183 Suns from Flickr (Partial) (2009), consisting of 1440 chromogenic color prints, Umbrico took screen shots of the thousands of sunset images (the most commonly shared image on Flickr) directly from the computer screen, cropped just the suns from each image, and had them printed by Kodak at 4 × 6 inches. The title reflects the number of hits she got searching “sunset” on Flickr, when she began the series in 2006, a number that only lasts a moment.

Her capture method produces a moiré pattern, an optical illusion, which facilitates the blending of the images into one another. This simultaneously causes viewers to go in opposite directions: being aware of the screen’s materiality makes the natural sunlight even more remote while recontextualizing all the original pictures into one big sun. Umbrico comments, “Looking into this cool electronic space one finds a virtual window onto the natural world.”28 In a twist of rephotography and making a full loop, people took pictures of themselves in front of the work, as if they were standing in front of a real sunset, and they posted their pictures on social media, making one wonder if anyone under thirty years old cares about the sun’s aura of originality?

In Mountains, Moving: of Aperture’s Masters of Photography (22 Westons) (2014), Umbrico utilized over 500 smartphone camera apps with their more than 6,000 filters to generate new photographs of canonical master photographs that include mountains. She finds these images in advertisements, books, magazines, and online, and she presents them both as prints and as a digital slide show. The moiré patterns blend with the hallucinogenic colors of camera app filters to produce fluid yet perplexing visual effects. Once again Umbrico establishes a discourse of opposites: original and copy, single and multiple, community and privacy, stability and variability, as well as technical correctness and mistakes, creating a dualistic sense of solidity and the transitory. This reflects the trend that the concept of the master photographer is fading as it becomes more difficult to declare a leader in a medium that is going in so many directions at once, and how the shift in context, from the Internet as opposed to a physical print-based media, can revise meaning and artistic significance.

For both digital and analog photographers, the good news about shifting from the print to the screen is that the Internet offers a vastly expanded photographic dialogue with social networking and video sharing websites, web pages, blogs, ezines, discussion groups, and chat rooms. “Today, every two minutes, people take as many pictures as were taken throughout the 19th century!”29making photography more egalitarian and relevant than ever. Social media image sites, such as Flickr, Instagram, and Tumblr, provide quick access to innumerable searchable images, becoming stiff competition to stock photography agencies. Some well-established photographers use such sites, not just for self-promotion, but also as a space to explore and disseminate new directions in their work. Many museums and public collections, including the Getty, the Library of Congress, and the MET are making parts of their holdings accessible online and allowing the public to download images for their own use. Artists, such as Mishka Henner (b.1976) in 51 U.S. Military Outposts (2010); Michael Wolf (b. 1954) in A Series of Unfortunate Events (2010); and Jon Raff-man (b. 1981) in 9-Eyes (2008—ongoing) are mining the virtual worlds of computer games, Second Life, and Google Earth or Street View as image sources of decisive moments that represent a new genre of Internet-based artmaking.

The Internet has also propelled the adoption of GIFs (graphic interchange format)—animated images applied by instant visual-messaging users on their mobile devices to express complex emotions and thoughts as a replacement for text and photographs. Generally, GIFs are a few seconds long, play in a soundless loop, and are often chosen from movie and TV clips. They can be a more effective form of visual communication than the emoji, as the movement in a GIF can deliver a wider range of expressions.

© MISHKA HENNER. Prime Base Engineer Emergency Force Camp Justice, Diego Garcia 7°20’S 72°25’E, 2010, from the series Fifty-One US Military Outposts, 2010. 59 × 59 inches. Inkjet print.

Henner uses the surveillance capabilities of Google Street View and satellite imaging to make work that reveals how the Internet has transformed our visual experience by ucidly capturing the human impact on the landscape.

COURTESY Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York.

This introduction of movement can be traced to the fact that most digital cameras can now record video and sound, and have been utilized as cost-effective tools in Hollywood and independent productions. Photographers have applied this feature not in the making of narrative movies, but in recording inventive performances that extend a photographic vocabulary to time-based media. It is now commonplace to see exhibitions where video work accompanies a photographer’s prints. This is yet another example of the blurring of boundaries between the artistic disciplines in which students are often taught to first be an artist, and then to choose the medium that best expresses their intentions.

Online auction sites, such as eBay, have facilitated the worldwide, everyday sale of historic and contemporary photographs and equipment. These auction sites have also turned sellers of other items into mostly straightforward photographers, and their homes into studios as they take pictures of their wares for online display. Additionally, digital book publishing services, such as Blurb, Lulu, and Shutterfly bring photography closer to the dream that Henry Fox Talbot expressed in The Pencil of Nature (1844) of everyone becoming their “own printer and publisher.”

The digital era ushered in a deluge of online blogs and discussion groups that examine and comment on photographic-based imagery. While this has vastly expanded the diversity of voices, the competition for attention has also fractured significant analysis into many small echo chambers of like-minded individuals with no particular critic leading a public debate that engages the entire field.

Digital imaging is just the latest evolutionary step in photographic imagemaking. Its importance lies not in the details of the process but in the largely unpredictable future of how it has and will transform our thinking. For instance, in the 1970s holography was heralded as a revolutionary form of imagemaking, but it remains chiefly used as a security device on credit cards, and in merchandise bar codes and on many currencies, including the dollar and the euro.

In the hands of an artist, even the smartphone camera can be subverted to push back against the digital tidal wave of algorithms and enable new forms of creativity. Dan Burkholder (b. 1950) works with a smartphone camera as a gateway to capture and process his images on-location, in the manner of plein air painters, with an array of inexpensive imaging applications. Burkholder asserts: “For the first time we have both camera and darkroom in the palm of our hands.”30 Utilizing this benefit, Burkholder reverses the usual electronic workflow by fusing a digital image with a handmade one. After in-camera processing, he enriches the digital image through an analog printing process that entails hand coating thin, vellum paper prints with platinum/palladium sensitizer and 24K gold leaf that fuses the subject’s appearance with his internal interpretation of it, adding a pictorialist-style physicality to the electronic image. By reintroducing the hand of the artist, Burkholder makes the point that “I am more concerned with emotional honesty than literal honesty in my photographs. My job is to respond to visual intrigue and beauty, and then to create a photograph that conveys to the viewer my feelings for the subject.”31

© DAN BURKHOLDER. Passing Sheep, Tuscany, 2013. Variable dimensions. Inkjet print.

COURTESY The Catherine Couturier Gallery, Houston, TX, and Sun to Moon Gallery, Dallas, TX.

Thus far, photographers have just scratched the surface of the transformative possibilities of digital imaging; the photography of the future will likely be a much different hybrid medium of pictures and sounds that combine on a screen, moving the medium further from its singular, object-oriented past, or possibly returning it to its origins in Daguerre’s Diorama (see Chapter 1).32

SCANNER AS A CAMERA

While the ability to electrically transmit a photograph over wires had existed since the beginning of the twentieth century it was not until 1957 that Russell A. Kirsch made the first digital scan of an image, a photograph of his infant son Waiden. Scanners operate as input devices that digitize information directly from printed or photographic materials in a method similar to photocopiers. Essentially a scanner is a compact, self-contained photographic studio, complete with optics and lights that produces images with an extremely limited depth of field. Light is reflected off or through an image or object and interpreted by light sensors. Color scanners use RGB filters to read an image in single or multiple passes. Scanners function like a focal plane shutter (see Chapter 8) in a conventional camera set to a low shutter speed. The image is exposed as a one-pixel-wide line at a time, a line that moves across whatever is on the scanner platter, whereas activity occurring elsewhere in the field of view is not captured. Motion is not recorded as a blur, but as a distortion in a predictable manner based on the speed and direction of the scanner’s movement. Scanners only capture very slow movements, while camera shutters can record the blurring effect of fast moving objects. The well-known 1912 image of a speeding racecar made by the young Jacques-Henri Lartigue (see Chapter 13) shows this phenomenon to pronounced effect. This can also be seen in the work of Carol Selter (b. 1944), who in the later 1990s placed live animals on her scanner, which recorded the dynamic patterns of their movement, dispensing with a Renaissance view of time as a single moment in space and offering in its place a fractured, almost cubistic way of seeing a subject.

© MAITHA BIN DEMITHAN. Still Waters, 2012. 35 ⅝ × 30 inches. Inkjet print.

Emirati artist Maitha Demithan (b. 1989) scans human figures in sections with the scanner placed directly on the bodies of her subjects and then digitally re-assembles the person. The resulting composite presents an objective and mechanical record as well as an emotional statement centered on the body’s forms and textures.

Other artists, like Maggie Taylor (b. 1961), who studied with and later married and divorced Jerry Uelsmann, embarked on utilizing a flatbed scanner instead of a camera in 1996 as the basis for forming surrealistic montages with romantic subtexts. Taylor conceptually shifts the nineteenth-century scientific aesthetic of Anna Atkins’s cameraless, cyanotypes and Lady Filmer’s Victorian domestic collages into the essence of unconscious association. Rather than physically building a collage piece by piece, Taylor manipulates digital layers to form unlikely juxtapositions of the nineteenth-century photographs and three-dimensional found objects that comprise her source materials. Her resulting fantastical iconography inspires the intuitive, subconscious mind to roam, launching different metaphoric/symbolic interpretations that allow each viewer to participate in the construction of meanings. Her work has become so iconic that it nearly constitutes a whole new genre of photographic images with many imitators.

© MAGGIE TAYLOR. Burden of Dreams, 201 3. 15 × 15 inches. Inkjet print.

Taylor tells us: “The scanner is very hands-on because I work with real objects, which I spend weeks modifying on the computer. I think of it in the same way as someone making a physical collage, except my configurations happen on a screen. My approach is spontaneous and open. Having infinitely changeable images allows me to step back-and-forth in time. This is an advantage for experimenting, as I am not permanently committed to decisions, as I would be if I were doing it manually. I do my own printing on a matte surface paper to have a more ink-on-paper feel. Overall, it’s a sticky issue as to whether you would say working digitally in this manner is hands-on or not.”33

DEATH OF THE PHOTOGRAPHER?

The death of photography has been proclaimed for years, but that is mere hyperbole, and it fails to acknowledge the medium’s continuous technical evolution. What has happened is that the assurance of silver photography’s fixed relationship to indexicality has been replaced by the assimilation of postmodernist ideas along with a flexible binary code in which an image is always open for re-interpretations. Unlike a photograph, a digital image does not authenticate one’s experiences, but rather transforms the process from producing a fixed, physical object into one that delivers fluid and mutable information. Entering the second decade of the twenty-first century, digital imaging has swept away photography’s original paradigm of straightforward objective truth and replaced it with a new multi-perspective system of depicting reality, much like how Cubism revolutionized seeing a hundred years before. For many imagemakers, this ambiguous area between reality and expression provides a creative opportunity and is one of photography’s current and longstanding strengths.34 This supports a challenge to the modernist orthodoxy with a return to ideas from Dada, Surrealism, and Constructivism (with their use of photomontage), as well as the often-criticized expressive pictorialist aesthetic of altering what the camera delivers to better communicate an artist’s personal vision.35

New technologies not only change the form and content of images, but also the ways in which photographers involve themselves in the imagemaking process. One can now purchase cameras designed to function without a photographer being present at all. Marketed primarily to wildlife photographers, these camouflage wrapped “game/trail” cameras rely on the motion of their subjects to trigger an exposure, taking photographers out of selecting the “decisive moment” and shifting their involvement to that of planner and editor. This recalls Philip-Lorca diCor-cia’s series Heads from the early 2000s, where he used a remotely activated camera and powerful strobe to photograph people in New York’s Times Square without them being aware that their images were being taken.36

Additionally, software is now being marketed that lets one place their action camera, such as a GoPro, onto a wireless charging mat that automatically syncs the raw video to “the Cloud,” Internet-based computing and data storage that shares resources as opposed to using personal devices to handle applications. The program then edits out what it considers to be the unexciting moments (lack of movement) and leaves only the action-filled ones.37 It can also merge footage from multiple cameras and locations into a single video without the maker’s input. The application responds to voice commands, with no need to operate physical controls. With such algorithms making decisions once made by humans, cameras with encoded composition guides and drones making automatic pictures based on programmed aesthetics are just around the corner.

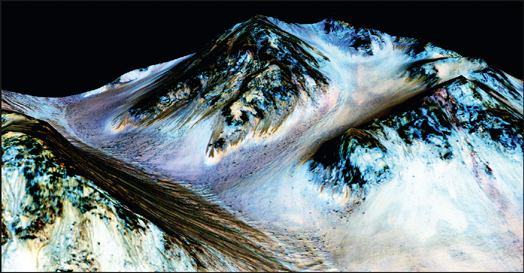

Such tools are facilitating the disappearance of the photographer, the requirement of individuals on the scene to make a photograph and imprint their personal style on the result. The public began to become aware of this during the 1970s as NASA came to rely more on teams of experts to construct digital images made by robotic cameras traveling in space that were transmitted back to earth, such as the Mars Viking Orbiter of 1975. The colors in these images are often synthetic, selected by scientists to better highlight specific data and they bear little relation to what a human observer might see were they present. Now we are confronted with sizeable numbers of automatic, private and public surveillance cameras plus satellites that can be seen in operation worldwide. These are often tied into government as well as law enforcement surveillance systems that permit nearly everything around us to be unobtrusively observed and photographed.38

Every day we are surrounded by photographic images that have no substance in reality. Just as a digital camera simulates the processes of chemical photography, we now replicate the action of light on objects and their depiction with a lens through 3D digital modeling and rendering tools. To accomplish this, objects are created three-dimensionally in the virtual space of a computer as structures called “wireframes.” These purely mathematical descriptions of forms are assigned physical properties such as color, reflectivity, texture and transparency. Often, photographic images are wrapped around these shapes to more closely match the real object. The artist then illuminates the scene with virtual lights and is ready for the final step called “rendering”— the equivalent to making a traditional photographic exposure. In a highly time-intensive process, the computer simulates the physics of light moving through a scene generating accurate highlights, shadows, and reflections for each pixel of a final image. When done with skill and sophistication, this technology can produce simulations of reality that are indistinguishable from ordinary photographs. The complexity of digital 3D modeling used in advertising, Ikea product photography, and movies, such as Avatar (2012), and Gravity (2013)40as well as the Lord of the Rings (2001–3) and The Hobbit (2012–13), requires a group of people with different skill sets to collaborate on each frame. Proclivities of individual panache and the belief that noteworthy breakthroughs are only made by solitary geniuses must often be set aside in these vast collaborative productions41

NASA. Recurring ‘Lineae’ on Slopes at Hale Crater, Mars, 2015.

Dr. Andrew Hershberger, professor of art history, informs us: “I often tell my history of photography students about seeing an exhibition of such NASA photographs at the Center for Creative Photography in the late 1 980s or early 1 990s. I thought then, and I still think now, how curious it was to see those photographs in that particular museum. The photographs were made in outer space, many during a NASA Mars mission, with no humans present. I thought then, and I still wonder now, can those photographs be regarded as ‘creative photography’? They were shown in the same galleries where Ansel Adams’s works had just been on display. I still do not know precisely how to answer that question, and that is yet another example of how the history of photography is so fascinating.”39

COURTESY NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona.

Computer experts from the Smithsonian and the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies teamed up to take the first 3D presidential portrait. The picture of President Barack Obama utilized a custom-built 50 LED light array; eight “sports” cameras, and six wide-angle cameras. The photograph was then 3D printed and is available for viewing at the Smithsonian. Like the work of artist Karin Sander (b. 1957), her series 1:10 (1999–2001) in which she digitally captures and 3D prints full figure portraits at one-tenth scale, this series harkens back to nineteenth-century death masks, where plaster was used to accurately capture a likeness, which foreshadows a fully three-dimensional form of photography.

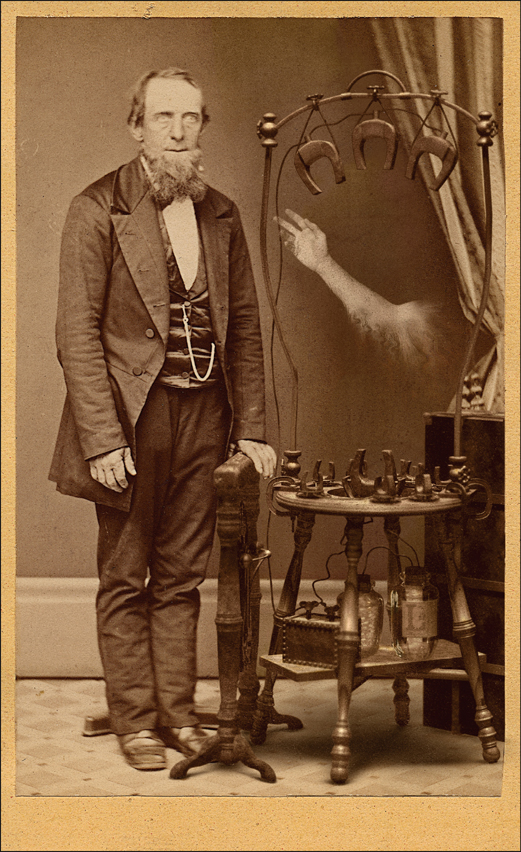

© EDWARD BATEMAN. Spectral Device No. 8, from the series Science Rends the Veil, 2014. Dimensions variable. Inkjet print.

Bateman tells us: “Mirroring my imagined spirit photographers, I do not have to rely on a physical presence to create an image. This allows me to question the idea that all photographs accurately represent a specific moment in time. To our contemporary eyes, the nineteenth century spirit photographs are clearly fraudulent. However, their work reflects a deep-seated desire to see the dead again—not as ghostly manifestations, but as meaningful and precious documents of those who once lived. The camera was the first machine of depiction and for a time people believed it to tell the truth. In the end, perhaps all images share this mixture of illusion and truth for it is in this soil that metaphor, the source of meaning, grows.”42

THE PHOTOGRAPHER’S EVOLVING ROLE

Artists employ these 3D digital modeling tools to make “photographs” without the presence of a physical object, throwing the accepted wisdom of photographic truthfulness and interpretation out the window. The Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung said that images provide the native language of the unconscious, suggesting how deeply rooted the creation of metaphor remains in the human psyche. Working with 3D modeling software gives artists the power and obligation to control and understand the symbols in their work. As the son of a psychiatrist and amateur artist/photographer, Edward Bateman (b. 1962) smartly and playfully upends photographic history and veracity by uniting the physical/real and the mental/imaginary to present bodiless spirits that metaphorically annihilate traditional photographic space and time. Although some elements in his work depict “real” things, many have never had a tangible physical existence. Instead, he modeled them in a computer that mimics light itself, one beam at a time, in a process that can take from hours to days to complete and that involves trillions of computer calculations. The results, created without a camera or a lens, seem like ghosts made of nothing more substantial than numbers; yet they seemingly share space with objects that have both physicality and history. As part of his malleable working process, Bateman employs dream interpretation techniques and strategies into his work, stating:

I see every object as being symbolic, creating links between the various elements in my images. Essentially, I construct visual synchronicity which can be loosely defined as meaningful coincidence, reflecting how our brains try to organize and make sense of our visual world. Meaning is seldom fixed, but exists in a fluid dance where associations are changed as effortlessly as identities in a Shakespearean play43

In turn, Bateman’s complex invented worlds startle viewers and invite them to explore his cultural symbols and make their own conceptual linkages by asking questions and following the threads to often surprising answers.

LOST AND FOUND

A truism in the nonlinear path of progress is that gain seldom comes without loss. As most schools and professional photographers have replaced their darkrooms with computers, there has been a reaction to the vanishing physical darkroom work. The magical darkroom experience of seeing an image develop in a tray of chemicals became an “Aha Moment” of discovery and insight for some people, setting them on a life’s path into photography. Many photographers still cherish how “the dimly glowing light, the sound of trickling water, and the acrid smells of acetic acid and fixer rising from the sink create an otherworldly environment that alters customary space and time, spurring the senses to circumvent the confines of familiarity and predictability”44 In past photographic practices, artists encouraged and embraced the material act of darkroom work to guide their outcomes. But just as the upswing of music samplers and synthesizers did not spell the end of acoustic instruments, a growing number of visual artists understand the expressive power of analog tools. Jerry Uelsmann explains: “I am sympathetic to the current digital revolution and excited by the visual options created by the computer. However, I feel my creative process remains intricately linked to the alchemy of the darkroom.”45

© MARK OSTERMAN. The Sixth Principle, from the series Tsukumogami 2014. 10 × 8 inches. Tintype.

Osterman’s series is based on Tsukumogami—a Japanese concept of inanimate household objects coming to life and causing mischief after 100 years.

COURTESY COURTESY Photo Gallery International, Tokyo.

Today the manual production of photographic prints by contemporary artists can be seen not as nostalgia but as a reaction to the pervasive, intangible perfection and often low quality online of digital images. It can also be an intentional act of rebellion against the importance many academics place on theories of practice and content. Under the gaze of postmodernist writers, photography has been posited as an intellectual activity, and coupled with digital photography’s similarity to a text on a screen, it is not surprising that fine art photographs are often valued more as illustrations for intellectual arguments than as objects of beauty, skill, and wonder. After all, it is more difficult to steal an idea than an image. Arguments aside, more artists now experiment with handmade processes, from pinhole to wet-plate photography, than at any time since the late 1980s. There is something deeply humanizing about the evidence of the artist’s hand in a work of art. The nuances and subtleties of our bodies’ interaction with physical matter have helped define corporal human experience over the millennia. This resurgence of interest in historical processes can be seen in the expanded participation of makers in symposiums like Tom Persinger’s annual F295 (2004–15), online with Malin Fabbri’s Alterna-tivePhotographic.com (2000-present), and in workshops offered by specialists like Mark Osterman (b. 1955) and France Sully Osterman (http://collodion. org). Equally important, many commercial galleries and museums still prefer pre-digital prints and they include non-traditional forms of photography in their exhibitions and collections.46

THE DIGITAL REVOLUTION WILL BE TELEVISED

In 1970 Gil Scott-Heron, a self-styled “bluesolo-gist” who foreshadowed modern hip-hop and early rap, recorded his sardonic protest poem/song, “The Revolution Will Not BeTelevised.” This title became a popular catchphrase among the 1960s Black Power movement, referencing racism, television shows, advertising jingles, plus news and entertainment icons that would not be in a new societal agenda. In effect, Scott-Heron proclaimed that “The revolution will be live.” In an interview, Scott-Heron stated:

UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHER. Punish With An Equivalent Of That With Which You Were Harmed, 2015. Video screen capture.

In a horrific propaganda video the brutal jihadi group ISIS obscenely burnt to death four Shia men accused of spying by chaining them upside down and setting fire to a trail of petrol that engulfed them in flames. The video’s title comes from Quranic verse 1 6:1 26, “And if you punish [an enemy, O believers], punish with an equivalent of that with which you were harmed. But if you are patient—it is better for those who are patient.”47

That song was about your mind. You have to change your mind before you change the way you live and the way you move… . The thing that’s going to change people is something that no one will ever be able to capture on film. It will just be something you see and all of a sudden you realize, ‘I’m on the wrong page.’48

Scott-Heron expressed an outlook that complacency, capitalism, and television culture would not bring about progressive social change. He added that international conglomerates control the media and feed the public its prerecorded viewpoints, denoting that the truth is live (and not live TV), and thus beyond the powers that be. The basic ingredient of all photographs—light—is thus separated from its natural context and transformed into artificial pixels, making even our sun a seemingly digital product.

Ironically, it turns out that most groups and people, from rappers to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), aka Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS/Daesh), rely on social media to reach their audience with images. These photographs play an important role as in how politicians no longer kiss babies, but instead have selfies made with people on the campaign trail.49 Selfies have become so prevalent, including the use of the selfie stick—an extendable arm onto which a smartphone camera can be mounted in order to take wide-angle photographs beyond the normal range of the arm—that the Russian government released a “Safe Selfie Guide” after a series of injuries and deaths involving their use.50 Although most online content is benign and simply self-serving, there is imagery that reveals the darker side of humanity. YouTube hosts Predator drone strikes that resemble video games. Another alarming aspect on social media is the data mining of faces that allows individuals to be remotely identified without their knowledge or permission, which could make public anonymity a thing of the past.52 At the limits of the criminal and barbarous, ISIL uses small digital video cameras to produce an Internet theater of death—beheading, burning, drowning, and blowing people up—making unconscionable brutality their brand as a method of intimidating infidels and for recruiting jihadists.

© YANG YONGLIANG. From The New World, 2014. 158 × 315 inches. Inkjet print.

Yang Yongliang’s (b. 1 980] turbulent yet tranquil images combine contemporary mega-cities with traditiona Chinese paintings, into works that are both Utopian and dystopian. He states: “If I love the city for its familiarity, hate it even more for the staggering speed at which it grows and engulfs the environment. If I love Chinese art for its depth and inclusiveness, I hate it for its retrogressive attitude. The ancients expressed their sentiments and appreciation of nature through landscape painting. As for me, I use my own landscape to criticize reality as perceive it.”51 Yongliang merges nature and man-made sprawl to address issues of constructed reality, societa identity and the chaos of our changing global world.

For electronic imagery to radically affect our consciousness and perception of reality, we need to get past the tidal wave of predictable, yet often entertaining, digital images that now circulate unendingly on the Internet. Artists, scientists, and scholars need to go beyond using computers as a convenient means for mimicking visions of the past, and discover the machine’s potential native diction(s). The distinction needs to be clearly made between what computers can do and what artists can do. The promise of digital technologies and a continuously networked culture provides an exciting arena for the creation of something new53 It not only changes the present and shifts the future, but also alters everything that went before it by giving artists new tools to translate inner perceptions into an outer presence that dispense with the analog of renditions of space and time.

With its emphasis on nonlinearity intertextuality and the development of multimedia, digitizing encourages the further hybridization of artistic practice, which in turn actively challenges the traditional divides between mediums and their attendant cultural spaces. Digitization heralds a rethinking of ideas surrounding cultural identity, nationhood, race, gender, and our sense of place and position. What digital imaging does not change is photography’s identity as a visual sign whose strength is its ability to represent the space between the constructs of the artificial and the “natural.” While the processes may change, artistic, representational thinking remains a fundamental ingredient in making us who we are; reminding us that pictures matter only to the extent that we matter and there is no critical system better than oneself. Here into the second decade of the twenty-first century, as the first generation of image-makers to have grown up with computers initiates its course and seeks to discover its own syntax, we are partaking in photography’s conceptual and practical shift from a medium that normally records reality to one that normally transforms it. In both scenarios, photography remains a medium in which we look for ourselves. The photograph continues to act as a manifestation of our society’s vital energies that we can use to ground ourselves, form memories, build identities and share via social media.

For a technology that is known for its literalness, photography has remained surprisingly adaptable in its ability to inspire artists in unexpected ways. Even with nearly two centuries of change, photography continues to reflect our society, engage the human spirit, and find new ways to fire our imaginations. Today the ubiquitous and omnipresent cellphone camera has replaced the once omniscient and all-seeing Eye of Providence. The 1930 prediction of Màrius Gifreda has come true where “the Zeiss lens will outdo the eye of Zeus, who sees everything but from too high.”54 Yet, as long as society values an accurate record of how things appear, the various processes for making photographic images will remain our visual benchmark for representing our world. What will be different is the acknowledgement that all photographic images are constructions—amalgams, clarifications and/or interpretations—made by the photographic auteur or by the camera program itself. This recognition will provide enriched opportunities for depicting a more complex reality that can encompass both the inner and outer dimensions of a subject while opening an unprecedented set of relationships between the subject and the viewer.

NOTES

1In 1965 Intel co-founder Gordon Moore observed that the number of transistors per square inch on integrated circuits had doubled every year since their invention. Based on this thought, Moore projected this rate of growth would continue for at least another decade, which roughly happened. However, in 2015 Moore forecasted that the rate of progress would reach a saturation point and Moore’s Law would start dying in the next decade or so.

2Theorists have debated whether digital photography is a “revolution” or not. See, for example, Fred Ritchin, In Our Own Image: The Coming Revolution in Photography (New York: Aperture, 1990); and compare articles by William J. Mitchell (1992) and EUen Handy (1998) that reinforce and debate this point in Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory: An Historical Anthology (Boston and Oxford: Wiley-Black-well, 2014), 382–83 and 344–49 respectively.

3Peter Plagens, “The New Real: Photoids,” Art in America, vol. 97, no. 2 (Feb. 2009), 67.

4See Adrian Campos, “How Kodak Is Recovering From Bankruptcy,” The Motley Fool, March 24, 2014, www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/03/24/how-kodak-is-re-covering-from-bankruptcyaspx

5This notion is encapsulated within the idea of photography’s “indexicality.” As with almost every aspect of photography, a large debate exists historically as to whether or not photographs are indeed indexical. For example, in Hershberger, ed., PhotographicTheory, see the introductions and texts to Charles Sanders Peirce’s “Logic as Semi-otic: The Theory of Signs” (circa 1900), 100–4; Rosalind Krauss’s “Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America’ (1977), 246—50; and Peter Geimer’s “Image as Trace: Speculations about an Undead Paradigm” (2007), 430–35, etc.

6Most photographic theorists agree that digital photography removes the materiality of the film and its required chemistry from the process and replaces them all with binary code. At least one theorist, however, disagrees that code itself is not material. See Johanna Drucker, “Digital Ontologies: The Ideality of Form in/and Code Storage—or—Can Graphesis Challenge Mathesis?” (2001) in Hershberger, ed., PhotographicTheory, 350–54. Drucker argues repeatedly: “I would strongly assert that the real materiality of code should replace the imagined ideality of code” (p. 351). She adds: “Code is also, always, emphatically material” (p. 353). Drucker also disagrees that digital images can be reproduced endlessly in identical copies. Instead, she argues that “there is loss and gain in any transformation that occurs as a part of the processing of information” (p. 354).

7A seemingly alluring juncture of the camera and the computer is the proliferation of 24-hour live camera websites where people encourage strangers to view, even ask questions, about the most intimate and generally trivial details of their lives.

8Oulimata Ba, “BBC Admits Blunder: ‘Gaza Under Attack’ Photos Fabricated,” HNGN, July 9, 2014, www.hngn.com/articles/35653/20140709/bbc-admits-blun-der-gaza-under-attack-photos-fabricated.htm. Other widespread instances were also made public regarding the coverage of the 2006 Lebanon War (aka 2006 Israel—Hezbollah War).

9Frank Van Riper, “Manipulating Truth, Losing Credibility,” www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/photo/essays/van-Riper/030409.htm. For an early survey of these issues, see Fred Ritchin, “Photojournalism in the Age of Computers” (1990), in Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory, 329–33.

10Vince Aletti, “An Israeli Photographer and His Panoramic Time Machines,” Village Voice, September 7, 2004. (www.villagevoice.com/art/0437,aletti,56701,13.html). This technique refers back to nineteenth-century pictorialist combination printing. See, for example, Henry Peach Robinson’s controversial advocacy of “Combination Printing” (1869) as reprinted in Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory, 12—IS. See also several criticisms of it by Robinson’s contemporaries and later photographers and theorists, p. 72.

11Truthiness is a quality characterizing a “truth” that a person making an assertion or argument claims to know intuitively “from the gut” or because it “feels right” without regard to logic, evidence, facts, or critical inquiry. In 2005, the American Dialect Society named it the Word of the Year. See: Dick. Meyer, “The Truth of Truthiness,” CBS News, www.cbsnews.com/news/the-truth-of-truthiness/

12Wikiality, a combination of the words “Wikipedia” and “reality,” was first used on the cable TV show “The Col bert Report” by Stephen Colbert, on Monday, July 31, 2006. It refers to the changing of reality or truth via a Wikipedia-like system, allowing reality to be determined by consensus.

13See David King, The Commissar Vanishes:The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 1997).

14See: False Memory Syndrome Foundation (www.fmsfon-line.org).

15Alexandra Wolfe, “Gregory Crewdson: When Photos Meet the Movies,” The Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2016, www.wsj.com/articles/gregory-crewdson-when-photos-meet-the-movies–1452277074

16Annette Grant, “ART; Lights, Camera, Stand Really Still: On the Set With Gregory Crewdson,” The New York Times, Sunday, May, 30, 2004, Section C, 20–21. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fuUpage.html?res=9800E3DB153EF933A05756C0A9629C8B63&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=l.

17Andrew E. Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory : An Historical Anthology (New York: Wiley Blackwell, 2014), 68–71.

18”Put Your Pictures on Your PC,” The Buffalo News, Sunday, July 18, 1999, Wegman’s grocery store supplement, 23.

19Michael Zhang,”Parents Are Naming Babies After Instagram Filters,” Dec. 1, 2015, http://petapixel.com/2015/12/01/parents-are-naming-babies-after-instagram-filters/

20See Jean Baudrillard, America, trans, by Chris Turner (London:Verso, 1988).

21In 2006 Gursky’s 99 Cent II Diptychon (2001) sold for $2.8 million. An extreme and sculptural example of this phenomenon is British artist Damien Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull, For The Love of God, which reportedly sold in 2007 for $100 million to an unnamed investment group.

22Ada Louise Huxtable, “Living With the Fake, and Liking It,” The New York Times, vol. CXLVI, no. 50,747 (Sunday, March 30,1997, Section 2), 1, 40.

23Thomas Demand. London: Serpentine Gallery; Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 2006. p. 56.

24Sarah Crompton, “Gained in Translation,” Telegraph, May 27, 2006. www.telegraph.co.uk/arts/main.jhtm-l?xml=/arts/2006/05/27/bademand27.xml&sSheet=/arts/2006/05/29/ixartleft.html.

25A Canon study of consumer trends said that almost 25% of people take more than 300 photographs a month with the most common subjects being family members, pets, and selfies. See Popular Photography, “The Lowdown,”July/ August 2016,13.

26Carla Marshall, “Cat Videos on YouTube: 2 Million Uploads, 25 Billion Views,” Tubular Insights, October 29, 2014, www.reelseo.com/2-million-cat-videos-youtube. A YouTube search of “Cat Videos” on July 6, 2016 yielded 32,100,000 results.

27Penelope Umbrico, “Some notes on my work,” http://penelopeumbrico.net/Info/Words.html

28Email with author, April 15, 2011.

29See: www.lesaviezvous.net/en/society/today-every-two-minutes-people-take-as-many-pictures-as-taken-through-out-the–19th-century.html. Yahoo! claimed about 880 billion photographs would be taken in 2014. See: www.popphoto.com/news/2013/05/how-many-photos-are-uploaded-to-internet-every-minute.

30Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 (New York and London: Focal Press, 2014), 165.

31Ibid.

32See Daguerre’s “Description of the Process of Painting and Effects of Light Invented by Daguerre, and Applied by Him to the Pictures of the Diorama” (1839), in Hersh-berger, ed., Photographic Theory, 31–34.

33Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960, (New York and London: Focal Press, 2014), 175.

34In 1950, Minor White called this area of highly productive tension a “spring-tight line.” See Andrew E. Hersh-berger, “The ‘Spring-tight Line’ in Minor White’s Theory of Sequential Photography.” In Anna-Teresa Tymieniecka, ed., Human Creation: Between Reality and Illusion (Dordrecht: Springer, 2005), 185–215.

35See A.D. Coleman, “Return of the Suppressed / Pictorialism’s Revenge,” Border Crossings, vol. 27, no. 4 (2008), 72–79. See also the section entitled “Postmodernism and Digital Imaging (Return to Pictorialism?) : c. 1990-c. 2010” in Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory, 319–39.

36DiCorcia’s Heads generated a debate between those wanting to protect an individual’s right to privacy and free speech supporters. In 2006, one of diCorcia’s subjects sued the artist and his gallery for exhibiting, publishing, and profiting from his likeness without his permission. DiCorcia said these images could not have been made with the subject’s knowledge. Free speech backers maintain that street photography is an established form of artistic expression and that the freedom to photograph in public is protected by the first amendment to the United States Constitution. Eventually, the lawsuit was dismissed. See Rachel A. Wormian, “Street Level: Intersections of Art and the Law Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s ‘Heads’ Project and Nussenzweig v. diCorcia,” GNOVIS, April 25, 2010, www.gnovisjournal.org/2010/04/25/street-level-inter-sections-art-and-law-philip-lorca-dicorcias-heads-pro-ject-and-nussenzweig/

37Nick Wingfield, “Camera Edits Out the Boring Parts,” The New York Times, August 10, 2015, B4.

38As of 2014, there were an estimated 245 million professionally installed video surveillance cameras active and operational globally. See Philip Ingram, “How many CCTV Cameras [closed-circuit television] are there globally?” June 11, 2016, www.securitynewsdesk.com/how-many-cctv-cameras-are-there-globally

39Email between Hershberger and the author, January 6, 2016.

40See Sophie Curtis, “The British Technology Behind Gravity’s Oscar-winning Visual Effects,” The Daily Telegraph, March 3, 2014, www.telegraph.co.uk/technology/news/10667457/Gravitys-Oscar-winning-visual-effects,html

41See Victoria Woollaston, “This is NOT a Real Woman,” Daily Mail, September 18, 2014, www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article–2761272/This-NOT-real-woman-Meet-Beryl-creepy-lifelike–3D-virtual-model-using-scans-elderly-ladyhtml#ixzz3f7ubZiPq

42Email between Bateman and the author, April 15, 2016.

43Email between Bateman and the author, July 13, 2015.

44Robert Hirsch, “Flexible Images: Handmade American Photography, 1969–2002,” exposure, 36:1 (2003), 31.

45Jerry Uelsmann et al, Other Realities (New York: Bulfinch Press, 2005), 2.

46For more information see Robert Hirsch, Transformational Imagemaking: Handmade Photography Since 1960 (New York and London: Focal Press, 2014).

47http://quran.com/16/126, May 7, 2016.

48See wwwyoutube.com/watch?feature=fvwp&NR=l&v=kZvWt29OG0s

49Jeremy W Peters and Ashley Parker, “Facing a Selfie Election, Presidential Hopefuls Grin and Bear It,” New York Times, July 4, 2015, www.nytimes.com/2015/07/05/us/politics/facing-a-selfie-election-presidential-hope-fuls-grin-and-bear-it.html?emc=edit_tnt_20150705&n-lid=15316572&tntemail0=y&_r=0

50Claire Voon, “Russia Releases ‘Safe Selfie’ Guide After String of Deaths and Injuries,” July 8, 2015, http://hyper-allergic.com/220698/russia-releases-safe-selfie-guide-af-ter-string-of-deaths-and-injuries

51Quote as translated by Thomas Bartz in “Mirror of Time,” in David Rosenberg, Yang Yongliang Landscapes (Hong Kong:Thircuir Ltd, 2011), 7.

52Marvin Heiferman, “Who’s Who? The Changing Nature and Uses of Portraits,” The New York Times, Nov. 16, 2015, http://lens.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/ll/16/whos-who-the-changing-nature-and-uses-of-portraits/?emc=edit_tnt_20151117&nlid=15316572&tntemail0=y&_r=0

53Perhaps Lâszlô Moholy-Nagy said it best when he advocated for art forms that ”produce new, as yet unfamiliar relationships’.’ See the introduction to Moholy-Nagy, “Light: A Medium of Plastic Expression” (1923), in Hershberger, ed., Photographic Theory, 130–31, esp. p. 130 (original emphasis).

54Màrius Gifreda, “The Zeiss Eye and the Eye of Zeus,” Mirador, 1930. As quoted in Joan Fontcuberta, Pandora’s Camera: Photography After Photography (London: MACK, 2014), 23.