Helping Employees Overcome Their Own Emotions

One of my lowest moments in customer service was when I deliberately hung up on a customer, knowing full well that if she called back and asked to speak to the manager she would get me on the phone once again.

It wasn’t the right way to handle things and I learned from the experience, but in that particular moment I let my emotions get the best of me. It wasn’t really that specific customer who set me off. A swirl of negative emotions had been building for quite some time, and this person was just the spark that ignited the blaze.

For starters, I didn’t like my job. I had accepted the position as the customer service manager for a small catalog company six months earlier, because my wife and I were moving to San Diego from Boston. I moved out first to get a job so that we’d have at least one income as we settled into our new hometown. It was the best job I could get in the three weeks budgeted for my job search, but I wouldn’t otherwise have chosen to work for this company. Even during the interview process I had the sense it was going to be a difficult place to work.

If you’ve ever had a bad boss, you know how hard it can be to go to work each day. I had two bad bosses: the company’s owners—who were also the president and CFO. They didn’t communicate well and often gave conflicting orders that pulled me in different directions, so I was constantly confused about my job responsibilities and main priorities. The company president was particularly unfriendly and angered easily.

The day I hung up on the customer was a week before Christmas. A perfect storm of three problems converged to cause a deluge of angry calls that went far beyond what you’d expect during the normal holiday rush. First, many of our most popular items were backordered and our supplier had just informed us that a delivery that could allow us to fill many orders would not arrive before Christmas, as we had expected. Second, major blizzards throughout the country had caused many shipments to be delayed or lost. Third, poor process control in our warehouse contributed to an extraordinarily high number of shipping errors, where packages were sent with the wrong item or to the wrong address. My whole team was working long hours and facing an enormous amount of stress.

On this particular day I’d already spent eight hours on the phone because we were drowning in calls. An alarm would sound throughout the entire company whenever a customer was on hold for more than a minute, and everyone in the company was expected to answer the phones when the alarm went off. My coworkers in other departments were frustrated with me because they were spending much of their day on the phone instead of doing their normal work. The president wouldn’t allow me to change the alarm setting to keep customers on hold longer before it sounded off, but even he was sending me angry e-mails because he too was spending a chunk of his day on the phone. However, I was completely powerless to stop the flood of callers.

I finally hit my boiling point with one particular customer. She was yelling insults at me as I tried in vain to apologize and find a solution. Click. I hung up.

I’m not proud of my action in that moment, but I’m grateful for the experience because it helped me fully understand how difficult customer service can be. Everyone who’s spent more than a few days in customer service has had similar experiences. After all, we’re all human!

In this chapter, we’ll look at ways that employees’ emotions can negatively affect their performance. We’ll see how our instinctive reaction when someone is yelling at us can easily lead to poor service. We’ll discover that negative emotions are contagious and can spread from customers to employees. Finally, we’ll examine how difficult it can be to smile when we just don’t feel like smiling. Companies that are committed to outstanding service must make it easy for their employees to be happy and help employees to develop skills to work through situations when they experience the negative emotions that come with the job.

“Don’t Take It Personally” Is Bad Advice

I can’t count how many times I’ve heard someone say, “Don’t take it personally” to an employee who’s upset after working with a difficult customer. I’m sure I’ve said it myself a few times. You may have had the same thought about me as you read my story at the beginning of this chapter.

But our natural instinct is to take things personally when other people are directing their anger or frustration at us. We’re likely to experience emotions such as anger, embarrassment, or even fear that can cause us to lash out at the other person or find a way to retreat. Expecting people to dismiss this normal reaction is like telling them not to laugh when they hear a funny joke or not to be concerned when they learn a family member has lost his job. It takes effort and training for employees to learn to manage their emotional reactions.

To understand why this happens, it’s helpful to turn to the work of Abraham Maslow, a psychologist famous for developing a list of factors that motivate people, often referred to as Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs. This framework describes our basic motivators in order of priority, where the first priority must be satisfied before we can be motivated by the next priority. For example, humans have a strong desire to be safe from physical harm, but people who have unmet physiological needs for food, water, or sleep would be willing to put their safety at risk in an effort to survive.1 Here is Maslow’s list of needs, in priority order:

1. Physiological

2. Safety

3. Love and belonging

4. Esteem

5. Self-actualization

I’ve trained thousands of customer service employees, and nearly all of them have a strong desire to be good at what they do. This intent fits squarely with self-actualization, which means the ability to perform at the peak of one’s abilities. However, people are motivated to be the best they can be only when all their higher-priority needs are being met. A customer directing a verbal tirade at an employee challenges the employee’s self-esteem, so the employee’s motivation to help the upset customer becomes a lower priority related to the need to protect his own self-esteem.

For example, here’s a real story from Paul, who was working in the office at a nightclub when he received a phone call from a customer who was upset because his credit card company had detected a fraudulent charge. The customer was convinced that a server at the club had stolen his credit card number. At first Paul tried his best to be helpful, but he quickly realized the man just wanted to vent. The customer’s repeated accusations, “Your server stole my credit card number” and “You guys need to be more careful,” soon wore thin. As Paul explained, “I could feel my blood pressure going up. I could feel my face get flush. I felt like, ‘Don’t accuse my coworker of doing something that you don’t know that they did.’ There are a million ways that credit card numbers get stolen. It was so frustrating to me.”

The customer’s uncooperative approach made it difficult for Paul to manage his emotions, despite his years of experience in the hospitality industry. It was insulting to hear the customer accuse one of his coworkers of a crime without providing a shred of evidence. The caller also repeatedly used the word you, which could have meant “the club,” but it was tough for Paul to avoid feeling like it was a personal attack.

Toward the end of the call, Paul stopped worrying about helping the customer because, he said, “I got to the point where I was so done with him. I started doing everything I could to get him off the phone.”

Working with upset customers is difficult, but it is even more challenging for employees to manage their emotions when they have a boss or coworkers who are unsupportive. The social structure provided by the workplace is a powerful part of most employees’ lives, and it’s often been noted that we spend more time with our coworkers than we do with our own families. This makes it vitally important that we have a sense of belonging at work, since—according to Maslow’s hierarchy—the human desire for love and acceptance is a more powerful motivator than esteem or self-actualization.

The day I hung up on my customer, I was having a hard time managing my emotions because two important needs weren’t being met. The customer’s tirade challenged my sense of self-esteem and frustrated me because I felt she was more interested in insulting me than in letting me try to assist her. Even worse, I was affected by a toxic work environment at a job I couldn’t stand, a boss who was angry at me for reasons I felt were his own doing, and coworkers who were frustrated with me, too. I experienced no sense of belonging during that moment and stopped caring about whether I did a good job.

A 2011 study by researchers at Bowling Green State University found a correlation between employee performance and the extent to which employees are subjected to mistreatment from customers and coworkers. The study, which focused on bank tellers at a regional bank, found that tellers who reported high levels of customer and coworker incivility were absent from work at least one more day per month than their colleagues. These same employees also experienced a 13 percent decrease in sales performance (as measured by their opening new accounts and selling additional products to customers).2

Clearly, companies need to offer their employees more than pithy advice to help them avoid resorting to poor service when confronted by an angry or upset customer. Employees need a supportive work environment that encourages their commitment to the team. They must also be helped to develop the skills they need to handle upset customers more effectively.

Companies that consistently deliver outstanding service base their success on a counterintuitive approach: They emphasize that employees, not customers, are most important. In Chapter 2, we discussed the importance of protecting employees from abusive customers as a way to encourage loyalty and commitment. Putting employees first promotes a sense of belonging and high self-esteem that ultimately leads to more positive relationships with both customers and coworkers.

Starbucks is an example of a company that embraces an employee-first philosophy. The company’s CEO, Howard Schultz, describes Starbucks employees as being central to the customer’s experience. “That experience can come to life only if people are proud, if they respect and trust the green apron and the people they are representing,” he has said publicly.3 This approach helps to explain why Starbucks appears regularly on both Fortune Magazine’s annual list of the 100 Best Companies to Work For4 and Bloomberg Businessweek’s annual Customer Service Champs list.5

I happen to be sitting in my local Starbucks as I write this passage. There are happy customers at every table and a line of people waiting to get their coffee. The employees cheerfully greet each customer and know many of the regulars’ orders by heart. The baristas expertly produce each person’s drink, dispense coffee, serve food, and ring up transactions in what looks like a well-choreographed dance behind the counter. This environment is created by coworkers who clearly like each other, their jobs, and the company they work for.

Of course, all customer service employees will occasionally encounter a customer whose anger is hard to handle. Effective customer service leaders keep in mind how difficult it is for employees to manage their emotions in these situations. Employees who are giving their best effort will benefit from a supervisor who helps them approach a customer service incident as a learning experience rather than a reason to take disciplinary action. A leader who is too quick to punish employees who give honest effort will likely lose their respect, so punitive measures such as written warnings, suspensions, and terminations are best reserved for willful acts of egregiously poor service, disastrous lapses in judgment, or an inability to learn from repeated mistakes.

There are three things that supervisors can do to help their employees learn from experience and improve their ability to manage their emotions in stressful situations. First, the supervisor should help the employee evaluate the situation and determine why the customer was angry. The intent isn’t to place blame, but rather to diagnose the root cause.

Second, the supervisor and employee should discuss strategies for getting better results when the employee encounters a similar situation in the future. Could the employee do or say something a little differently? Is there an opportunity to diffuse the customer’s anger before it boils over?

Finally, the supervisor should encourage employees to apply these new strategies on the job. This supportive approach will make employees more likely to be forthcoming, asking their supervisor for help rather than trying to prevent the boss from hearing about an incident with a difficult customer. It also fosters a spirit of continuous improvement where employees get better and better at handling difficult situations over time.

For customer service employees, the job is even more challenging because emotions are contagious. Encounters with angry customers can leave employees feeling irritable, and that feeling can linger as they interact with other customers. Likewise, particularly outgoing customers can make employees feel upbeat and help them deliver a higher level of service to people they subsequently encounter.6

Looking back at that inglorious day when I hung up on a customer, I now understand how contagious emotions played a role in my actions. It seemed as if I was receiving anger from all sides. My boss was angry at me, my coworkers were annoyed with me, and my customers were furious. I was becoming angrier and angrier with each person I encountered. This anger reached its apex with the customer who wouldn’t stop insulting me.

It may be tempting to observe situations like mine and think that customer service employees should simply resist getting infected with other people’s emotions. Unfortunately, the contagious effects of other people’s emotions are often experienced unconsciously. Employees might not even realize an upset customer is making them angry until the anger begins to impair their ability to provide good customer service.

In 2000, researchers at Uppsala University in Sweden published the results of an experiment that confirmed how people can unconsciously react to emotions expressed by others. Subjects in the experiment were exposed to images of people who were either smiling or looked angry. These images were flashed on a screen for just thirty milliseconds, which is too short a time for the conscious brain to notice the image, but long enough for the unconscious brain to process it. The happy or angry pictures were closely followed by an image of someone with a neutral expression that was displayed for five seconds. Throughout the experiment, subjects were connected to tiny electrodes that allowed the experimenters to measure the subjects’ facial reactions.

The electrodes detected facial movements in the subjects that aligned with the pictures they were unconsciously exposed to. The group who saw images of people smiling displayed a higher level of activity in the muscles used to smile, while the group who saw pictures of angry people had a higher level of activity in the muscles that create a frown. None of the subjects was aware of seeing the happy or angry faces when debriefed after the experiment.7

You can have a little fun conducting your own version of this experiment by smiling at strangers in public. It works particularly well in a crowded area where many people are passing by, such as an airport or a shopping mall. Try to make eye contact and smile at people as they pass by and you’ll be amazed at how many complete strangers automatically smile back.

Contagious negative emotions don’t come exclusively from customers, bosses, and coworkers. Factors outside the work environment can influence employees’ emotions. Personal problems, such as having an argument with a spouse, a sick child, or financial difficulties can all contribute to a sour mood. Something as simple as an inconsiderate driver encountered during an employee’s morning commute can infect that employee’s state of mind.

Companies that offer outstanding service strive to make their work environments as positive as possible. Positive emotions are just as contagious as negative feelings, and upbeat employees lead to happier customers and coworkers in a self-reinforcing cycle. These organizations foster an enjoyable work environment by helping employees create strong bonds with their coworkers, bosses, and the company as a whole.

Encouraging friendships among coworkers is an important first step. According to Tom Rath, a researcher at Gallup, employees with at least one coworker who is also a close friend are seven times more likely than other employees to be engaged in their jobs.8 Friends make it easier for employees to keep their spirits high and to recover from negative situations.

Of course, friendships at work must form naturally, but companies can influence their development through a variety of strategies. Here are a few examples:

• Holding informal social events after work encourages employees to interact with one another in a casual setting.

• Varying work schedules and project assignments gives people the opportunity to work with a variety of coworkers.

• Hiring employees in groups or “cohorts” helps them become friendly with one another as they go through the shared experience of being new employees.

Bosses can also play a big role in helping employees maintain a positive frame of mind. A supportive supervisor helps employees recover quickly from encounters with difficult customers. On the other hand, an unfriendly boss generates negative emotions that tend to lead to poor service.

Supervisors need supervision, too. Executives need to be in tune with employees two or more levels below them so that they understand the impact supervisors are having on morale. Some organizations choose to augment direct observations with periodic 360-degree surveys in which managers are evaluated by their employees, or through workplace climate surveys where employee satisfaction is assessed along multiple dimensions, including their relationship with their direct supervisor.

This leads to the third level of responsibility: Senior executives need to make the company a place where employees want to work. It should be seen as a refuge, so even those employees experiencing personal problems can feel as though their burden is lifted when they come to work.

In 2010, 32 percent of companies on Bloomberg Businessweek’s annual list of the top-25 Customer Service Champs were also on Fortune Magazine’s list of the 100 Best Companies to Work For. Companies that make the Best Companies to Work For list have supportive leaders who inspire trust and a workplace where employee friendships are abundant. They tend to offer a better package of compensation, benefits, and other perks than their competitors because they understand the benefits of attracting top talent, having low turnover, and encouraging loyalty and productivity. Most important, employees have a sense of pride in their work and understand the value of their contributions to the company’s success.9

The High Cost of Emotional Labor

Most customer service positions have standards governing the emotions that employees should express to their customers. These standards, called “display rules,” include typical service behaviors such as making eye contact, smiling, and addressing people with a warm and friendly tone. They may be explicitly defined in a procedure or set of customer service standards, or implicitly expected as part of our cultural norms for customer service professionals.

Display rules are easy to follow when they’re in sync with our genuine emotions. Smiling, making eye contact, and warmly addressing customers come naturally when we’re in a good mood. However, these same rules can be exceedingly difficult to follow when our true emotions don’t match. An employee who is experiencing anger, sadness, or frustration is still expected to smile at customers, but it’s very hard to make that smile appear genuine.

Customers are usually able to perceive the difference between sincere expressions of emotion and employees who are engaged in what’s called “surface acting,” where the displayed emotion doesn’t match the person’s true feelings.10 The airline industry is often cited as an example where people observe a stark contrast between the expected display rules and how flight attendants actually feel. Pacific Southwest Airlines (PSA) even played to this notion when it ran a funny ad campaign in 1979 called “Our Smiles Aren’t Just Painted On.” The commercials emphasized the authentic service of PSA flight attendants in contrast to competitors’ disingenuous attempts to appear friendly.11

As a frequent traveler, I often have the chance to observe the gap between flight attendants’ real and displayed feelings. I can overhear their candid conversations while riding on an airport shuttle bus or sitting near the galley on the airplane. Of all the airlines I’ve experienced, Southwest Airlines’ flight attendants seem to be the happiest with their jobs, their coworkers, and their lives in general. This genuine happiness easily carries over to those moments when they are serving passengers. On the other hand, I’ve often observed flight attendants from other airlines complaining about their jobs, coworkers, or personal lives. This attitude clearly impacts their quality of service. This may be one more reason that Southwest Airlines consistently offers some of the best service in the airline industry.

The effort required to bridge the gap between the display rules and your actual emotions is known as “emotional labor.” A little bit of emotional labor can be expected in any customer service role, but employees experiencing a large gap between their actual and displayed emotions over a prolonged period of time are highly susceptible to burnout. In much the same way that physical labor can tax our energy, exerting high amounts of emotional labor can leave people physically and mentally exhausted.12 Employees experiencing burnout ultimately leave their jobs or—worse—continue in their positions long after they’ve stopped trying.

In 2005, the Wall Street Journal MarketWatch site surveyed a group of trade associations and human resources experts to compile a list of the ten occupations with the highest employee turnover. Not surprisingly, seven out of ten of these high-burnout jobs are in customer service. All of the positions require employees to regularly exert a high level of emotional labor.13

The costs of employee burnout and turnover are significant. There are direct costs that are fairly easy to calculate, such as the cost of recruiting, hiring, and training new employees to replace the ones who leave. Indirect costs, such as lost productivity and decreased revenue due to poor performance, are much harder to calculate precisely but are often far greater than the direct costs.

I once worked with a hospital to help reduce turnover among the staff of 200 nurses. The annual turnover rate was 30 percent, meaning the hospital had to hire an average of sixty nurses every year to replace those who left. The direct cost of hiring and training replacements was $300,000 per year. However, the hospital’s chief financial officer estimated the indirect costs associated with turnover, including lost productivity, lower patient satisfaction, and decreased levels of patient care, were as high as $3,000,000 per year, or ten times as much as the direct costs. These indirect costs were hard to capture and measure, so an exact tally was elusive, but there was clearly a huge impact.

My work with this client focused on helping the hospital create a more positive and engaging environment. Management adjusted its hiring practices to find nurses who would be more likely to enjoy working there. It improved training programs to provide nurses with skills to effectively handle stressful situations. The hospital’s managers learned how to provide more positive feedback and recognition to improve the work climate. Within eighteen months, these efforts paid off and the turnover rate was cut in half.

Emotional labor was another obstacle I faced when I hung up on that customer many years ago. My dislike for my job and my bosses was so strong that it was getting harder and harder to go to work each day. I started getting sick more often and found myself becoming increasingly irritable around my employees, my friends, and even my wife. As a customer service manager, I was expected to model all of the display rules you’d expect from a service employee, but my true emotions rarely matched those expectations.

Eventually, I felt burned out and began to look for a new job with a better work environment. As luck would have it, I quickly received two job offers. One position was as customer service manager for another call center; the other was as a customer service trainer for a parking management company. The call center job paid 20 percent more and was in an industry I was familiar with, but a quick tour of the work environment told me this company’s culture wouldn’t be much different from the one I was trying to escape from.

Despite the substantially lower salary, the customer service training position was more in line with my dream job. The person who would be my boss seemed wonderfully supportive and committed to creating an engaging work environment. In our interview, she spoke about her passion for the company and how the organization was truly committed to world-class customer service. The potential coworkers I met during the interview process were all intelligent, dedicated people who seemed like they’d be fun to work with.

Choosing the training job over the call center management role was one of the easiest career decisions I’ve ever made. I distinctly remember making the call to accept my new job while on jury duty. The emotional labor of my soon-to-be-former job was so taxing that jury duty was a pleasant respite. Who’d imagine that being out of the office for three days while serving on a jury would seem like a vacation?

There are two strategies that companies can use to help their employees avoid the painful effects of high levels of emotional labor. The first is to create a positive and supportive work climate, which has already been discussed in this chapter. The second strategy is to help employees in high-stress situations find ways to recover, much the same way you need to physically recover after a strenuous workout.

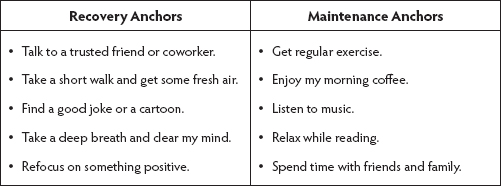

My favorite recovery technique is an “attitude anchor.” An attitude anchor is something that secures your attitude in a positive place. For example, if I need help recovering from a stressful encounter with a customer, I might spend a few moments chatting with a trusted friend to lighten my mood and reset my attitude to a more positive frame of mind. Attitude anchors can also be used to maintain a healthy and positive outlook, such as regularly catching up with close friends regardless of whether I need their support in that moment.

Attitude anchors are inherently personal, so what works for one person may not work for someone else. Supervisors can help employees identify their own attitude anchors by having them make a list of “recovery” and “maintenance” anchors. I’ve listed mine in Figure 10-1.

Figure 10-1. Attitude anchors.

Solution Summary: Helping Employees Overcome Emotional Roadblocks

Customer service is an emotional job. There are highs associated with knowing you helped someone, and there are lows that come from working with challenging customers, coworkers, or bosses. Helping employees avoid or manage negative emotions is essential to creating an organization that consistently serves its customers at the highest level.

Here is a summary of the solutions offered in this chapter:

• Make employees, not customers, the top priority for the organization. The employee-first approach fosters a supportive work environment, promotes a sense of belonging, and encourages self-esteem.

• Meet with employees—in a supportive and nonjudgmental way—after they have encountered an angry customer to help them learn from their experience and develop skills for handling similar situations in the future.

• Encourage employees to develop friendships with their coworkers, so they’ll find more enjoyment in their work environment.

• Ensure that supervisors apply a positive and supportive leadership style that encourages dedication and commitment from employees.

• Make your company a place where employees can easily leave their personal troubles behind and look forward to coming to work each day.

• Help employees identify their personal attitude anchors to help them maintain a positive outlook or recover from a negative encounter.

Notes

1. A. H. Maslow, “A Theory of Human Motivation,” Psychological Review 50 (1943), pp. 370–396.

2. Michael Sliter, Katherine Sliter, and Steve Jex, “The Employee as a Punching Bag: The Effect of Multiple Sources of Incivility on Employee Withdrawal Behavior and Sales Performance,” Journal of Organizational Behavior 33, no. 1 (August 2011), pp. 121–139.

3. Adi Ignatius, “We Had to Own the Mistakes,” HBR Interview with Howard Schultz, Harvard Business Review, July 2010.

4. Archives of Fortune Magazine’s annual “100 Best Companies to Work For” can be found at CNNMoney.com (http://money.cnn.com/magazines/fortune/best-companies/). Starbucks was ranked No. 24 in 2009, No. 93 in 2010, and No. 98 in 2011.

5. Archives of Bloomberg Businessweek’s annual “Customer Service Champs” list can be found on www.businessweek.com/archive/news.html. Starbucks was ranked No. 10 in 2007, No. 6 in 2008, and No. 13 in 2010.

6. Elaine Hatfield, John T. Cacioppo, and Richard L. Rapson, “Emotional Contagion,” Current Directions in Psychological Sciences 2, no. 3 (June 1993), pp. 96–99.

7. Ulf Dimberg, Monika Thunberg, and Kurt Elmehed, “Unconscious Facial Reactions to Emotional Expressions,” Psychological Science 11, no. 1 (January 2000), pp. 86–89.

8. Jennifer Robison, “What Are Workplace Buddies Worth?” Gallup Management Journal, October 12, 2006; http://gmj.gallup.com.

9. Fortune partners with the consulting firm Great Place to Work to compile its annual list. You can learn more about the criteria and selection process by visiting the website www.greatplacetowork.com/our-approach/what-is-a-great-workplace. There are also many “best places to work” awards sponsored by local chambers of commerce, business newspapers, or human resources associations. These awards typically have published criteria that you can use to benchmark your organization against proven best practices.

10. Alicia A. Grandey, “Emotion Regulation in the Workplace: A New Way to Conceptualize Emotional Labor,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5, no. 1 (2000), pp. 95–110.

11. You can view a number of PSA’s ad campaigns on the online PSA history museum: www.jetpsa.com. One of the commercials is also easy to watch on YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OOtv1lQ3Sgw.

12. Grandey, “Emotion Regulation in the Workplace.”

13. Kristen Gerencher, “Where the Revolving Door Is Swiftest: Job Turnover High for Fast-Food, Retail, Nursing, and Child Care,” MarketWatch.com, February 23, 2005; www.marketwatch.com/story/job-turnover-highest-in-nursing-child-care-retail.