Chapter 3

The Need for the Science of Service

A wireless communication service provider usually offers a variety of service plans. Wireless service plans, such as a 2-year contract with 600-min monthly usage individual cell phone plan, a 2-year contract with 1000-min monthly usage family cell phone plan, limited or unlimited data and messaging plans, a global positioning system (GPS) navigation plan, and different bundle plans, are popular ones in the United States. A service product does not create any utilitarian and/or sociopsychological benefit until it is consumed. For instance, a customer chooses a competitive 2-year plan with a cellular phone the customer likes. The value cocreation process that defines a service starts at the point when the customer calls a representative, browses the service provider's website, or visits a provider's retailing store to sign up the plan. If the service can meet the needs of customer's daily communications, the customer will be most likely satisfied with the service. Of course, the service provider makes a corresponding profit until the customer terminates the signed service contract.

In the above-discussed example, if the customer experience is outstanding in all aspects with respect to today's highly competitive wireless communication services, the customer most likely becomes a loyal customer and will continue to choose a service product from the service provider in the future. The customer's word of mouth, including posts, blogs, and conversations over varieties of online social media, effectively attracts more customers, intentionally or unintentionally. In business, if the wireless service provider can execute the service plan well, the provider makes a profit from such a service. Loyal and lifetime customers surely help the service provider win the increasingly intensified competition in the marketplace (Heskett et al., (1990); Heskett et al., (1994); Schneider and Bowen, (2010). As the total values of the provided service are the values, respectively, accumulated by the customer and the service provider throughout its service lifespan, it is the progression of executing the service plan that truly determines the real values beneficial to the customer and the service provider.

As discussed in Chapter 2, service can be simply defined as an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences and manifest itself as a service encounter chain to cocreate benefits, respectively, for service providers and customers. A valuable, beneficial, and competitive service surely is the operational outcome of a well-operated and managed sociotechnical service system. Given the increasing complexity, dynamics, and scope of services, it becomes essential for a service organization to apply the science of service to the operations and management of its whole service delivery networks (a.k.a. sociotechnical service system) to ensure that the promised services can be performed in a competitive way in the current and future service-led economy.

Science is commonly recognized as knowledge. In a given discipline today, the organized body of knowledge as a disciplinary science is radically derived from systematic observations of focused social or natural phenomena. It is well known that the systematic observations help us to discover and organize knowledge in the form of laws and principles about the observed social or natural phenomena in the universe. Indeed, the formulated laws and principles allow us to test the explanations and make predictions for further investigation and exploration. In this chapter, by taking a holistic and systems perspective we discuss an approach on how we can take steps with scientific rigor to study services and service systems.

3.1 A Brief Review of the Evolution of Service Research

Service research in several focused areas, including service operations, marketing, and organizational structure and behavior, and economic transformation, has been conducted worldwide for many decades. Reviewing all very influential service research literature that contributed to the service research, development, and practice at time when the work was done is not the purpose of this chapter. However, it is worthy of briefly highlighting many pioneer research work that continues to substantially impact current service research. Note that this brief highlight could be quite limited as it simply reflects the author's viewpoint (Qiu, (2012).

As early as in the 1970s, a rational approach deviating from the traditional physical-product-based rationalizations was explored by Chase (1978), aimed at identifying a new course to help organizations understand and manage service business operations by addressing the newly confronted service-oriented challenges in business back in the 1970s. Larson (1989) has been a longtime proponent of applying operations research and management science to improve services business operations. Recently, applying optimization and queuing theory in solving a variety of managerial and operational problems in service systems is comprehensively discussed by Daskin (2011).

Considerable research efforts have significantly contributed to the development of service marketing and economics. Lovelock (1983) pioneered the education and exploration of modern service marketing and leadership with a focus on the synergistic effects by fully leveraging people, technology, and strategy in service organizations. Grönroos (1994) has been leading the study in service management by applying service logic to market-oriented management in service and manufacturing firms. By comprehensively analyzing the profitability drivers throughout the service-profit chain, Heskett et al. (1994) argue that putting employee and customers first would radically make a shift in the way service organizations manage and measure success. How service quality can be financially accountable has been specifically investigated by Rust et al. (1995), giving rise to further exploration of marketing investments, customer equity, and relationships in services.

As discussed in Chapter 2, because the developed economies further moved away from producing goods to providing services after the turn of this new millennium, Vargo and Lusch (2004) strongly propose a new service dominant logic focusing on intangible resource, the cocreation of value, and service-for-service exchange relationships in the service marketing field. The service-dominant logic thinking has been well incorporated into the research in the fields of organizational structures, employee behavior, and economic transformation (Vargo and Akaka, (2009); Hilton and Hughes, (2013); Löbler, (2013).

Karmarkar (2004) then emphasizes the industrialization of services and argues that service organizations can survive the ever-changing business environments because of the digitalization and globalization only if they can effectively reorganize strategies, processes, and people within and across organizations for the unprecedented challenge ahead. Hsu (2009) shows how a theory of service scaling and transformation through leveraging digital connections could contribute to the development of Service Science for the knowledge economy. In particular, he advocates that digital connection scaling plays a key role in value cocreation for providers and customer.

When the worldwide economy was dominated by goods, both academics and practitioners paid much attention to the development, production, and innovation of physical products (Chesbrough, (2003). Because physical products were essentially the focus, production/service organizations were more or less considered as technology-driven organizations or systems. Consequently, when service research was conducted, physical goods-dominant thinking was frequently taken for granted.

However, as discussed in Chapter 2, the emphasis in the developed economy has been shifted away from manufacturing to service since the 1960s. As compared to goods-dominant thinking, service-dominant thinking must have people clearly identified and centered across the lifecycle of service. The interactions between service providers and service consumers play a crucial role in the process of transformation of the customer's needs utilizing the operations' resources. The value of service lies along with the process trajectory throughout the lifecycle of service. Therefore, the behavior of systems of a sociotechnical service system should be well designed, managed, and operated with the full support of Service Science (Spohrer and Riechen, (2006); Qiu et al., 2007; Qiu, (2009), so that an effective and satisfactory service path toward the realization of business objectives can be formed in an optimal manner. A service path is nothing but a sequence of relevant service business activities, which typically manifest themselves to a customer as an event-based series of service encounters.

Despite the recognition of the importance of service research, the shift to focus on disparate and global-scale services (Karmarkar, (2004) and the servitization of products (Chase and Erikson, (1989) to compete in the service-led global market has created an education and research gap (IBM, (2004); IBM Palisade Summit Report, (2006); Dietrich and Harrison, (2006). The gap has not been fully filled largely because of the granted physical goods-dominant thinking and the prior lack of the means that allowed us to fully explore the people-centric systemic interactions and their sociotechnical impacts on service system dynamics in the service research. According to Spohrer et al. (2007), “the role of people, technology, shared information, as well as the role of customer input in production processes and the application of competence to benefit others must be described and defined.”

In summary, the science of service, or service science, must be explored, clearly defined, and well developed. When the discovered service theories, laws, and principles are applied in practice, practitioners can effectively manage and control systemic behavior and leverage sociotechnical effects in a service system, so that the system can be scientifically and wisely guided to maneuver throughout the process-driven service lifecycle to create, develop, and deliver valuable, beneficial, and/or competitive services.

3.2 Service as a Process of Transformation

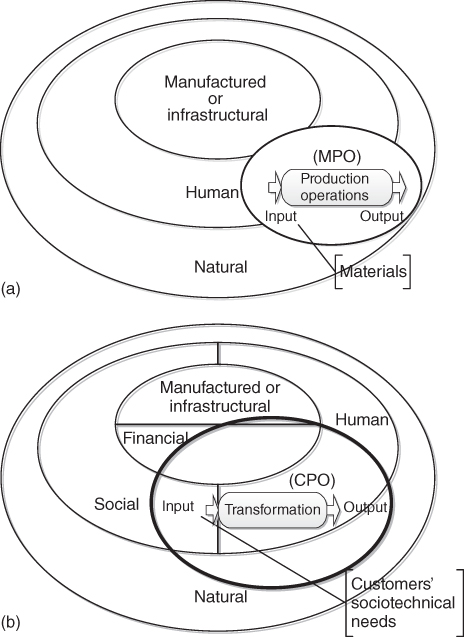

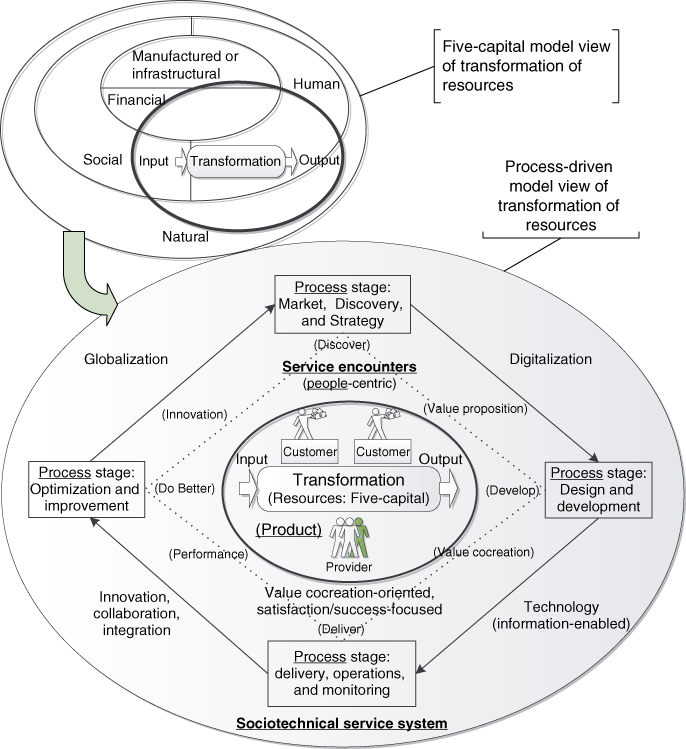

From the preceding chapters, we understand that the word of “service” has many connotations, which varies with business domains and settings. A very good paper from Morris and Johnston (1987) provides a great discussion on the inherent variability between manufacturing and service operations management. They classify three types of general production operations, characterized by the inputs that are processed rather than the outputs of the processing operations: material processing operations (MPOs) (Figure 3.1a), customer processing operations (CPOs) (Figure 3.1b), and information processing operations (IPOs).

Figure 3.1 Goods-dominant production operations versus service-oriented transformation. (a) Goods-dominant production operations in the resource model and (b) service-oriented transformation in the five capitals model.

Morris and Johnston further discuss the differences among the three types of general production operations. They differentiate service from manufacturing by the nature of the thing that is processed. The CPO acts upon a customer to create sociotechnical and economic effects on the customer. The IPO processes information to convert it into a desirable form. The MPO processes input materials and then produces goods. Manufacturing organizations are largely MPO-based entities. Service firms are then mainly CPO-based. They argue that issues such as capacity planning, operations planning and control, inventory or queue management, and quality control must be considered in each of the three types of operations. However, as service is inherently different from manufacturing, the inherent difference must be well considered in service operations and management by service organizations to ensure their successes in business.

Figure 3.1a uses the simple and traditional three categories of resources: natural, human, and manufactured or infrastructural resources to highlight the inherent nature of goods-dominant production operations in which materials are the input. Natural resources essentially are the source of raw materials. Human resources consist of human efforts provided in the transformation of the materials into physical products. Surely, manufactured or infrastructural resources, consisting of man-made goods or means of production (e.g., machinery, buildings, computers, networks, and instruments), must be utilized in the processing operations to make the transformation cost-effective and efficient (Morris and Johnston, (1987); Samuelson and Nordhaus, (2009); Sullivan et al., (2011).

As discussed in Chapter 2, the economic shift from manufacturing to service entails a disruptive change in business, transforming the way business would operate in the service-led economy. A process of transformation that focuses on people-centric service encounters surely becomes the organizational and business core in a service organization. Table 3.1 highlights the disruptive change and shows the focus shift in service business operations and management. The intangibility, heterogeneity, simultaneity, perishability, customer participation, and cocreation are the key commonalities across disparate services businesses (Sampson and Froehle, (2006).

Table 3.1 Main Characteristics Comparison Between Service and Goods

| Focus | Service | Goods |

| Production | Cocreated | Produced |

| Variability | Heterogeneous | Homogeneous |

| Physicality | Intangible | Tangible |

| Product | Perishable | Imperishable |

| Satisfaction | Expectation-related | Utility-related |

In response to the social, political, economic, and environmental issues in today's globalized economy, the Forum for the Future (FftF) as a nonprofit organization proposes the five capitals model, a framework for sustainability. In addition to the traditional three categories of resources, the five capitals model further includes social and financial capitals as shown in Figure 3.1b. The five capitals model provides a basis for organizations to consider the impact of its business activities on each of the capitals in an integrated manner. As a result, this resource model allows organizations to implement a responsible and balanced business model to ensure their sustainable outcomes in the long run (FftF, (2012).

On the basis of the definition of service concluded in Chapter 2, service is essentially an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences and manifests itself to customers as a service encounter chain that substantively reveals the cocreation of benefits, respectively, for service providers and customers. As the service encounter chain is essentially created and managed through a process of transformation as illustrated in Figure 3.1b, a good understanding of social and human capitals in an organization becomes important (Lepak and Snell, (2002). According to the FftF (2012), human and social capitals are well defined as follows:

- “Human capital incorporates the health, knowledge, skills, intellectual outputs, motivation and capacity for relationships of the individual. Human Capital is also about joy, passion, empathy and spirituality.”

- “Social capital is any value added to the activities and economic outputs of an organization by human relationships, partnerships and co-operation. For example networks, communication channels, families, communities, businesses, trade unions, schools and voluntary organizations as well as social norms, values and trust.”

Simply put, we must emphasize cocreation-oriented business activities between service providers and service consumers throughout the service lifecycle. More specifically, people's social, physiological, and psychological traits must be fully and explicitly explored, understood, and incorporated into the process of transformation of customers' sociotechnical needs by service organizations for competitive and sustainable outcomes.

From the early discussion, we understand that because CPO is the rudimentary business operational paradigm in service organizations, service-oriented operations must focus on transforming “customers” instead of materials that are used in MPO. In other words, the shift from materials to “customers” as the input to CPO indicates that customers' sociotechnical needs should be the main concerns in a service-oriented transformation. In service business, a service thus is a process of transformation of customers' sociotechnical needs with the support of operations resources, fostering and operating positive service encounters to meet the needs of customers and providers. Therefore, capturing customer's needs and leveraging customers' participations in the process of transformation of customers' sociotechnical needs truly play a key role in service operations and management.

3.3 Formation of Service Encounters Networks

Now it is well understood that service is a transformation process that takes “customer” as its input. Both provider-side and customer-side people must be involved in an interactive manner, applying relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences to cocreate benefits, respectively, for service providers and customers. For a given service, the interactions, service encounters, essentially function as the delivery mechanism of rendering the promised service. Therefore, we must have a full understanding of service encounters in order to grope for a new approach to a creative and comprehensive study of service science.

Let us briefly review what we discussed about a service encounter in the preceding chapters. A service encounter essentially is a social and transactional interaction in which a service provider performs a service activity beneficial to its corresponding service customer. To a service customer, a service encounter is a moment of truth for the wanted service with which the customer interacts. To a service provider, a service encounter is an act of communicating and rendering the promise.

The PDGroup project service example in Chapter 2 is a good source for us to revisit how service encounters are crucial in delivering a successful and satisfactory service. Throughout the project cycle, we briefly discussed some indispensable interactions between different groups of consultants from the PDGroup and employees from the ChemGlobalService who are located across different continents. Here, we would like to emphasize the challenges and discuss what might impact the outcomes of the PDGroup project service in both a short term and the long run.

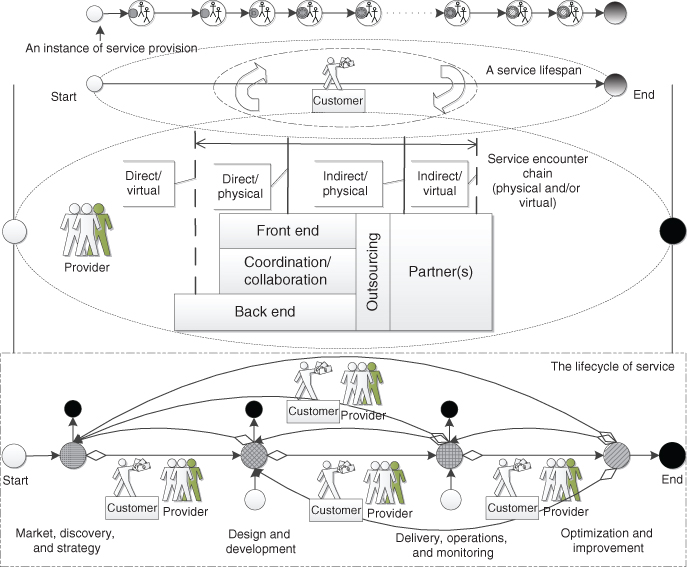

Assume that ChemGlobalService initiated the first interaction by consulting with the PDGroup for a possible project service. A memorandum of understanding or preliminary service agreement might be written before the project got started. A project draft specification would then be brainstormed when the top-level management group from the PDGroup met with a group of customer representatives from ChemGlobalService. The customer-side participants from the organization- and unit-level at different facilities of the ChemGlobalService would be critical for identifying the challenges at the systems level. Onsite visits might also be needed, focusing on collecting the detailed requirements at the operations level. A final service agreement is typically signed off during this stage. A series of service encounters that occurred along with the progression of the project development form a service encounter chain (Figure 3.2), which is essentially described as an instance of a service encounter graph in theory.

Figure 3.2 An instance of service derived from a service encounter graph.

At the design and development phase in the PDGroup project service example, numerous direct and productive interactions would be essential to ensure that the technical and nontechnical requirements would be fully considered. For instance, the project specification would be revised and further enriched after this phase was kicked off. Unless the project is completed, it is typical that the specification would keep changing to some extent. Surely each revision would be the outcome of many onsite or virtual meetings among related representatives from the ChemGlobalService and all teams, that is, Team A to Team G, from the PDGroup. Effective communication means should be established so that customer representatives could be directly or indirectly contacted by PDGroup project group members whenever additional end users' inputs are needed.

The most intensive and productive interactions throughout the service lifecycle in the PDGroup project service example should occur at its delivery, operations, and monitoring phase. Most likely, people from Teams A, B, C, D, and E would have to be involved. The PDGroup must make sure that end users will be well trained; the daily business operations would thus be well coordinated and monitored among three facilities. Frequently, service encounters at this phase would be direct and physical. In fact, the study of service quality in this phase by the literature has been voluminous as scholars and practitioners around the world have paid exceeding attention to these direct interactions that must occur in delivering services and to how these service encounters impact the perceived service quality by both the service providers and the service customers (Czepiel et al., (1985); Parasuraman et al., (1988); Czepiel, (1990); Bitner et al., (1990); Bitner et al., (1997); Bradley et al., (2010).

At the optimization phase in the PDGroup project service example, many productive interactions should also be required to ensure that the weakness of the delivered integration project and occurred service encounters would be well and promptly identified. In particular, Teams A and G would have more interaction with related representatives from ChemGlobalService, aimed at understanding the weakness of the deployed solution and identifying new additions in support of the ongoing changes of business operations and management.

For any given phase in the service lifecycle, the literature has shown many outstanding works. For instance, the technical requirements within services are most likely materialized in service products with the support of operations resources. How service encounters substantially impact perceived service quality in a variety of dimensions from the perspectives of the service providers, customers, or both has been well studied (Taylor, 1977; Parasuraman et al., (1988); Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992); Chase and Dasu, (2001); Svensson, (2002); Bradley et al., (2010). However, these human interactions, in general, have not well explored as they have not been considered throughout the service lifecycle in an integrative and collaborative manner. In other words, how these intensive and broad interactions at one phase impact other phases of service provision have been largely ignored so far in service research. We must rethink service encounters by integrating these human interactions into a service encounter chain, from beginning to end across the service lifecycle, so that we can look into services defined in this book using a holistic, systems, and integrative approach (Qiu, (2013b).

To extend the popular cross-section service quality studies in the literature, Svensson (2004) proposes a framework for exploring sequential service quality in service encounter chains, that is, examining the consecutive service performances in a series of service encounters during the service delivery processes. Conceptually, Svensson provides a customized six-dimensional construct of sequential service quality to highlight the importance of time, context, and performance threshold in service encounter chains. Although Svensson's conceptual work has not well validated empirically or theoretically, the service encounter chain concept certainly sheds some light on our groping for an alternative direction of further developing service science.

“At the heart of every service is the service encounter” (Heskett et al., (1990), p. 2). To develop a holistic, systemic, and integrative approach to the scientific study of service, the concept of service encounters should be further extended from the old one focusing on the study of service quality and satisfaction at the delivery, operations, and monitoring phase to a new one spanning the total service lifecycle. In other words, all interactions between the service providers and the customers as a whole across the service lifecycle should be explored and analyzed.

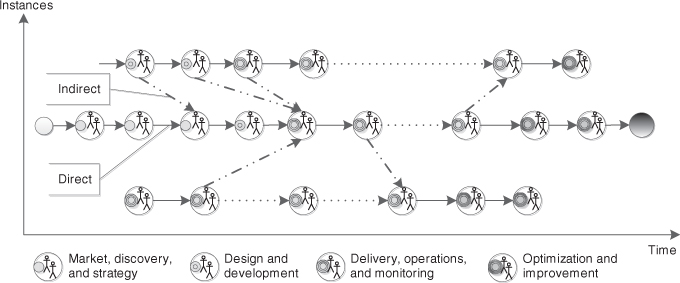

The first three service encounters in the middle instance shown in Figure 3.3 provides a graphic view of the occurrence of these types of service encounters at the market, discovery, and strategy phase in the PDGroup project service example. They will surely, sequentially, and substantially impact the service quality and value perceived by customers in the later phases, directly or indirectly. Put in a broader context, for a given service encounter chain, essentially, the preceding service encounters impact the current service encounter and the succeeding ones, psychologically, socially, and economically.

Figure 3.3 Service encounter chains to form a service encounter analytic network.

The effectiveness of the deployed project solution in the above-mentioned example largely depends on a series of positive and productive service encounters that must occur in a timely, efficient, and effective manner. At each point of customer interaction, customer experience is the perceived effect of the fulfillments in both functional and socioemotional dimensions (Durvasula et al., (2005); Chase and Dasu, (2008); Qiu, (2013b). Functional needs are met by performing desired service functions that are specified in a signed service agreement. Meeting the psychological needs of customers and employees becomes extremely challenging as socioemotional needs manifested through an array of psychological needs vary with time, duration, and servicescape, and individual's expectation and competency (Bitner, (1990); Bitner, (1992); Bitner et al., (1994); Bitner et al., (2000); Svensson, (2004); Meyer and Schwager, (2007); Bradley et al., (2010). Moreover, these psychological needs at a service encounter are frequently influenced directly and indirectly by the outcomes of the preceding service encounters as illustrated in Figure 3.3.

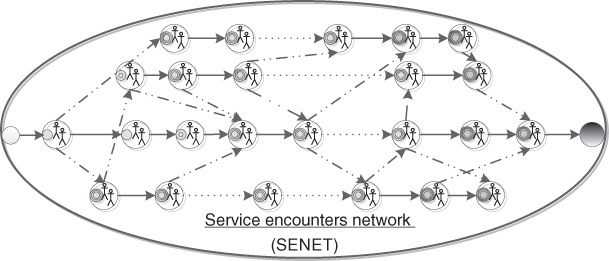

As discussed earlier, varieties of service encounters throughout the lifecycle of the global project development service are collaborative in nature. An individual's service lifespan varies with his/her role at work. As a value cocreation and service-oriented interactive activity, each service encounter certainly makes a difference, positively or negatively impacting the final outcome of the rendered service (Lloyd and Luk, (2009); Svensson, (2006). To the service provider as a whole (i.e., PDGroup's perspective), the sum of all the series of service encounters spanning the service lifecycle indeed creates a service encounters network (SENET) (Figure 3.4). Hence, the values of the provided service for the provider and the customers largely depend on the efficacy and effectiveness of planning, operations, and management of the SENET throughout the lifecycle of service.

Figure 3.4 An illustration of SENET.

3.4 Inherent Nature of Sociotechnical Service Systems

As the world is now all connected economically, technically, and socially, service organizations must integrate products and services into solutions that are desirable, amicable, and environmentally sustainable. Because services dominate the developed economy and radically drive the growth of the world economy, service firms must continuously improve their service business competitiveness that is clearly characterized by customization, integration, intelligence, and globalization in order to serve their diversified customers across the continents. Indeed, over the last decade or so we have witnessed that this new service-oriented social business wave, through leveraging the advancement of IT and the diversity of cultures and societies, provides end users better satisfaction and quality of life—the ultimate prosperity goal of human being (Palmisano, 2008; Qiu, (2009).

A system, focusing on the interdependence of relationships created in an organization, is composed of regularly interacting or interrelating groups of activities within the organization (STWiki, (2012). From the systems' perspective, a service system essentially consists of a number of interacting business domains entities that must be well coordinated (Qiu, (2007); Qiu, (2013a). A service system can simply be a software application, or a business unit within an organization, from a project team, business department, to a global division; it can be a firm, institution, governmental agency, town, city or nation; it can also be a composition of numerous collaboratively connected service entities within and/or across organizations. No matter what a service system is, small or large, individual or composed, and intra- or interconnected, it must radically consist of people, technologies, infrastructures, and processes of service operations and management (Spohrer et al., (2007); Spohrer, (2009).

Generally speaking, a competitive service organization is a well-built, controlled, and managed service system. The systems view of a service organization is then a perspective of looking at the service organization as a collection of business domain systems that create a whole, allowing us to understand and orchestrate the interacting activities among these business domains systems. As discussed earlier, today's competitive service organizations must put people (customers and employees) rather than physical goods in the center of their organizational structures and operations. Moreover, real-time explorations of human behaviors and sociopsychological dynamics within services become essential for service organizations to stay competitive in the information era.

Because service firms must focus on engineering and delivering services using all available means to meet both technical functional and socioeconomic needs and accordingly realize respective values for both providers and consumers, service firms essentially are social-technical service systems. The fast advancement in distributed computing and interconnected network has significantly increased the role and power of IT and communications, transforming the ways how the service industry operates. We are sure that the science of service can be fully developed in the near future. We believe that service firms can be realistically operated as effective socio-technical service systems using service-dominant thinking while leveraging the increased flexibility, responsiveness, and capability of service business operations and management (Qiu, 2013a), resulting in improving business operational productivities and delivering new high levels of job and customer satisfaction (Qiu, 2013b).

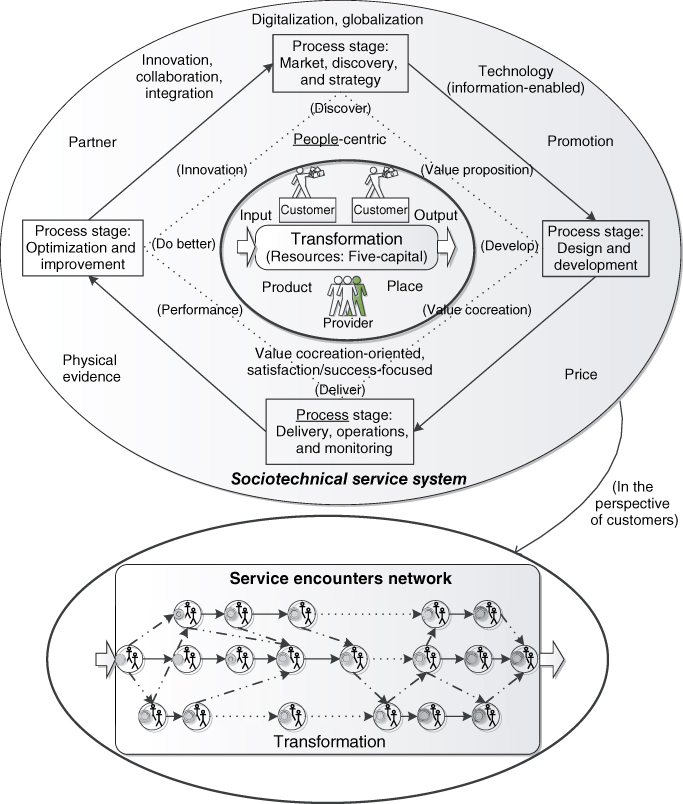

As the world is becoming better instrumented and interconnected, and more intelligent, a service system must be people-centric, information-enabled, service-oriented, and satisfaction-focused; it should encourage and cultivate people to collaborate and innovate (Qiu, (2009). The incorporation of the five-capital model into the process of transformation or service provision provides a clear and conceptual illustration of a sustainable socio-technical service system (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5 A sustainable socio-technical process-driven service system.

No matter what service is conceived, designed, developed, and delivered, whether the functional and socioeconomical needs are fully met and the served customer is completely satisfied rely on the efficient, effective, and smart operations of its service-oriented value delivery network, that is, an integrated and collaborated heterogeneous service system (please refer to Figure 3.2). It is well known that competitive systems are not always at equilibrium as time goes; they are very dynamic and adaptive. A service organization as a service system or ecosystem surely becomes more integrated and capable while more dynamic, complicated, and challenging than ever before (Qiu, (2009).

“Indeed, almost anything from people, object, to process, for any organization, large or small—can become digitally aware and networked” (Palmisano, 2008). On one hand, the world becomes smaller, flatter, and smarter, which creates more opportunities and enormous promise; on the other hand, more challenges and issues appear in many aspects from business strategy, marketing, modeling, innovations, design, engineering, to operations and management in order for businesses to stay competitive in a globally integrated economy. Consequently, an enterprise has to rethink its operational and organizational structure by focusing on people (e.g., implementing a novel approach to overcoming social and cultural barriers to cultivate and enhance the cultures of cocreation, collaboration, and innovations), so as to ensure the prompt and cost-effective development and delivery of competitive and satisfactory services for customers throughout its geographically dispersed while digitally integrated dynamic service systems (Qiu, (2009). More detailed discussions of digitalization of service systems will be provided in the next section.

In summary, regardless of the complexity and type of service provision that is enabled by a service system, it is typical that a service consists of a series of social and transactional interactions. We understand that the series of service encounters can be direct or indirect, consecutive or intermittent, physical or virtual, and brief or intensive. Regardless of the occurring time and servicescape of a service encounter, each service encounter that constitutes the offered service plays its unique role in contributing to the final service outcomes. The value of service indeed relies on the sociotechnical efficacy and effectiveness of the total occurred service encounters throughout the service lifecycle. The successful operation of a service system thus largely depends on whether its formed SENET-oriented operations can be well performed, monitored, and controlled. Therefore, service systems must be efficiently and cost-effectively managed, realizing their business objectives and goals tactically and strategically.

3.5 Digitalization of Service Systems

Enterprises have benefited from building collaborative partnerships with geographically dispersed partners. Hence, businesses are frequently operated under the umbrella of global virtual enterprises. This becomes a common practice as enterprises can fully leverage the best-of-breed goods and service components at a more competitive price while meeting the changing needs of today's on-demand business environment. As the competition in the global economy unceasingly intensifies, without exception, service organizations must leverage their digital connections to scale and transform, internally and externally, so that they can meet their consumers' fluctuating demand for innovation, flexibility, and shorter lead time of their provided services (Chesbrough, (2011a).

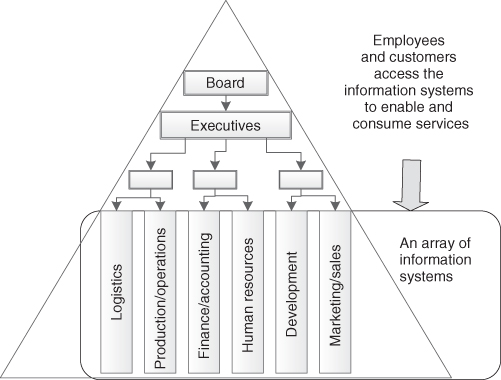

Figure 3.6 Information systems in support of all business domains in organizations.

Internally, business domain or enterprise-wide information systems in support of all aspects of business operations and management in an organization are essential (Figure 3.6). It is the information technology (IT) that enables real-time information flow. Consequently, the right data and information in the right context can be delivered to the right user (e.g., people, machine, device, component, etc.) at the right place and right time, facilitating efficient and effective coordination across business domains within the organization. For instance, the top management can pinpoint business weakness areas and make the informed decisions accordingly with the support of the real-time information on sales, finances, production, and resource utilization of the organization. In general, the enabled and fostered coordination among business domains results in the substantial increase of the degree of business process automation, the continual increment of production productivity and services quality, the reduction of service lead time, and the improvement of job and customer satisfaction (Qiu, (2007); Berman, (2012); Qiu, (2013a).

Because a variety of devices, hardware, and software become network aware, almost everything is currently capable of being handled through the networks. Services can be completed onsite if necessary; while many tasks or functional e-service components can also be done remotely or even self-performed over the Internet. Indeed, at the end of the day, end users do not care about how and where the products and services were made or engineered, by whom, and how they were delivered; what the end users or consumers essentially care about is that their functional and sociopsychological needs are met in a satisfactory manner. In today's globalized and service-led economy, it is the total customer satisfaction and loyalty that drives further and more sales.

Under the unceasingly increased pressure of market competitions, organizations have to be capable of offering and delivering services fast and cost-effectively. In an organization, the employed business operations are essentially derived from its adopted corporate best practices. Managerially, daily business operations are largely reflected and driven by varieties of domain-based business activities that are logically grouped as an array of business processes. Operationally, these business processes are mainly executed by its employees with the support of the deployed enterprise information systems across the organization. A significant portion of business operations might be fully or partially automated by complying with an array of predefined business processes. However, it is also normal for an organization to have a number of ad hoc business processes in operation to meet the uncertain or changing needs of employees and customers. Therefore, the enterprise information systems in use in the organization must be efficient, adaptable, ready for integration, and easy to make changes in order for the organization to stay competitive in business from time to time (Qiu, (2013a).

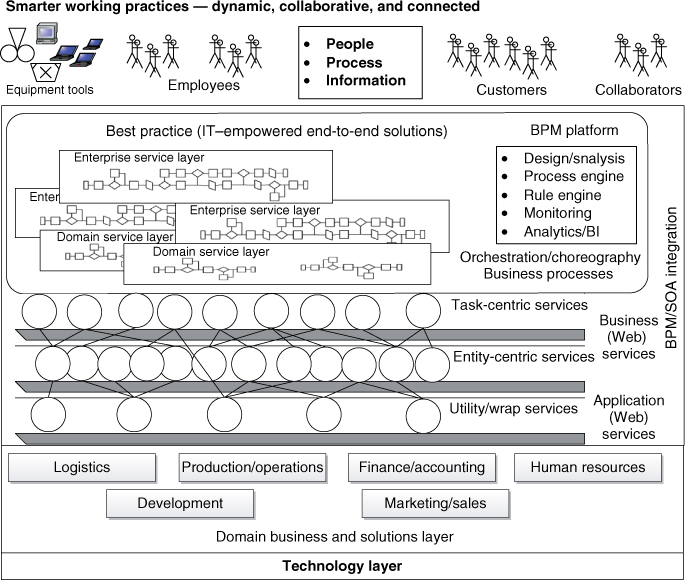

In a service organization, business processes are fully involved with people, tools, and information. Information technology (IT) makes possible the digitalization of the whole organization or socio-technical service system from the systems' perspective. As shown in Figure 3.7, the realization of dynamic, collaborative, and connected ways of business operations with the support of well-integrated enterprise information systems defines smarter working practices, resulting in greater agility than ever before in business (Pearson et al., (2010); Qiu, (2013a):

- Dynamic. Instead of retaining static and rigid ways of executing business operations, organizations full of processes, people, and information should be capable of being adjusted rapidly to the changing needs of employees and customers.

- Collaborative. Instead of relying on a monolithic system (or so-called a monopoly business model), organizations apply best-of-breed service models in practice, focusing on the capability of fully leveraging resources (including people, tools, and information) to share insights, solve problems, and cooperate business operations, internally and externally.

- Connected. Telecommunications and networked computers make possible the delivery of the right data and information to the right users at the point of need, regardless of time and location. The world becomes flattened. People and communities are more connected than ever before, so are the business operations across organizations nationally and/or internationally, which surely make today's business operations naturally collaborative across organizations, nationally and/or internationally.

Figure 3.7 Smarter working practices with the support of integrated information systems.

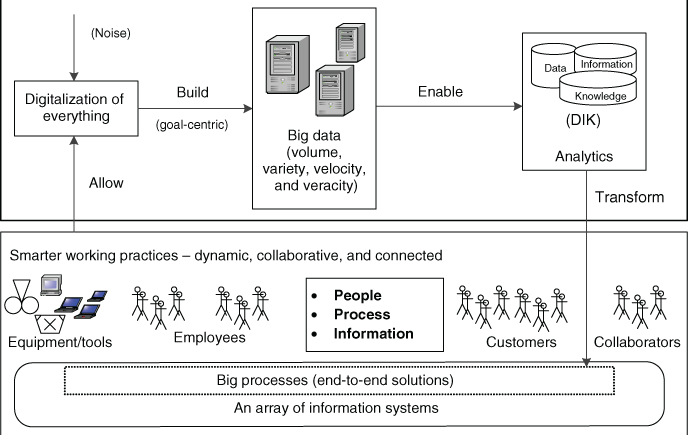

Digitalization of service systems makes possible for us to capture and understand customer experience in service provision in a comprehensive manner (Drogseth, (2012); Ahlquist and Saagar, (2013). Over the years, we have seen that data are overwhelming everywhere and data volumes are exponentially growing year by year. However, the majority of data coming from disparate and heterogeneous sources are either semistructured or unstructured; thus, conventional approaches and tools that were designed to work with large structured data sets simply cannot handle this big data. New analytic methodologies and frameworks must be explored and introduced to the market to help service organizations bring order to the big data from diverse sources and thus harness the power of the big data. By doing so, service organizations can glean the insights and values and also grope for new opportunities that were previously unattainable. This is particularly critical for service organizations to implement SENET-oriented service systems because of the fact that the people behavioral data are typically overwhelming and utterly unstructured (Figure 3.8).

Figure 3.8 Big data and processes enabling SENET-oriented service system.

Indeed, the economic globalization has been accelerated with the advancement of networking and computing technologies over the past two decades or so. IT currently plays a more and more critical role in enabling and supporting business and societal development collaborations across the world. Service organizations can leverage the five capitals in an effective and sustainable manner. Particularly, world-class service organizations must take advantage of human capitals including the cultural diversity and focused-area talents to deliver satisfactory services across the continents. Nowadays, not only service organizations but also competitive manufacturers eagerly embrace service-led business models to build and sustain highly profitable service-oriented businesses. They take advantage of their own unique ways of marketing, engineering, and application expertise and shift gears toward creating superior outcomes to best meet their customers' functional and sociopsychological needs in order to outperform their competitors (Rangaswamy and Pal, (2005); Qiu, (2007).

Distributed computing and interconnected networks have made IT ubiquitous and pervasive over the years, and thus have significantly increased the capacity and capability of IT in service organizations. Information-enabled systems have continuously increased the flexibility, responsiveness, and capability of business operations. As a result, competitive service organizations have unceasingly improved their productivities and job/customer satisfactions. Regardless of the involved service complexity and nature, a service organization makes every effort to make the organization as a sustainable sociotechnical process-driven service system (Figure 3.9), so as to join and stay in the world-class business club.

Figure 3.9 Sustainable sociotechnical process-driven system.

As discussed earlier, with the push of ongoing “industrialization” of the information technologies, digitalizing information across all business domains in organizations allows the information on service provision to be fully preserved, accessed, and shared within or across organizations. By creating integrated, scalable, and adaptable value networks through collaborating with geographically dispersed business partners, service organizations are capable of delivering their service-led total solutions to customers efficiently and cost-effectively. Note that the value of a delivered service lies in its ability to satisfy an end user's functional and sociopsychological need, which apparently is not strictly seen in the physical attributes and technical characteristics of the provided product or the technical functions of the delivered service.

3.6 An Innovative Approach to Developing Service Science

As discussed earlier, today's service concept has dramatically evolved beyond the traditional nonagricultural and/or nonmanufacturing performance in delivering customers' benefits. For example, many new emerging high value areas, such as IT outsourcing, after-sales training, on-demand innovations consulting (e.g., consulting services that help customers innovate and improve their product designs, business processes, goods and services delivery operations, and IT systems' efficiency and effectiveness), are well recognized as services, drawing substantial attention from many industrial bellwethers. As a result, the service sector nowadays covers from commercial transportation, logistics and distribution, health care delivery, training and education, financial engineering, e-commerce, retailing, hospitality and entertainment, issuance, supply chain, enterprise knowledge discovery, transformation and delivery, to a variety of high tech and high value consulting services across different industries.

Regardless of service business types, “service drives sale” is not a secret in the current service-led economy. On one hand, unique and satisfactory services differentiate an organization from its competitors; on the other hand, delivery of highly satisfactory services frequently drives more product or service sales for the organization to outperform in its marketplace. As the shift from manufacturing to services becomes inescapable from the developed countries to the developing countries, organizations are gradually embracing for service-oriented business models by defining and selling anything as a service. Note that the service-led economy not only conceptualizes a quantitative increase in the percentage of GDP, more importantly, also indicates a substantive shift in which the service sector must become a main driving engine for future economy growth and innovation.

3.6.1 Service Value Chains in the Service Encounter Perspective

As discussed in the preceding chapters, regardless of many definitions of service existing in the literature, all definitions are more or less based on the same fundamental concept. That is, service is considered as an application of relevant knowledge, skills, and experiences to cocreate benefits, respectively, for service providers and customers. To a customer, the encounter of a service or “moment of truth” frequently is the service in the customer's perspective (Bitner et al., (1990). However, from the perspective of a service system, service is a process of transformation of the customer's needs utilizing the operations' resources, in which dimensions of customer experience manifest themselves in the themes of a service encounter or service encounter chain.

Centered at both provider-side and consumer-side people in services, service encounters are mainly interaction-focused and inherently dyadic and collaborative both socially and psychologically (Shostack, (1985); Solomon et al., (1985); Lu et al., (2009); Schneider and Bowen, (2010). Surely it is a service encounter that enables the necessary manifest function that engages the providers and the customers in order to show the “truth” of service. For example, consumers are the customers in the retailing service sector; students are the customers in educational service systems; patients then are the customers in health care delivery systems. Service is a process of transformation of customer needs; service takes time to complete, resulting in reciprocal influence between service providers and customers. In the extant literature, service encounters within a service largely considered all interacting activities involved in its corresponding service delivery process. In this book, we advocate that a service organization should explore all service encounters across the lifecycle of service, groping for the optimal opportunities and outcomes in services to stay competitive in its marketplace.

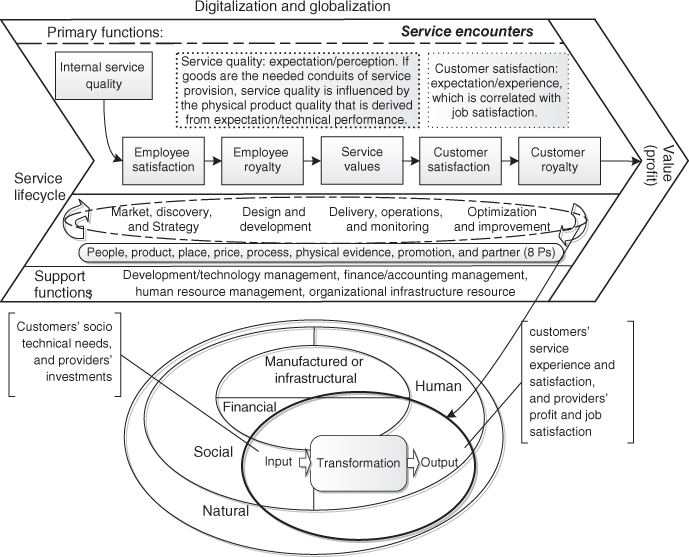

The quality of a provider's services is the overall perception that results from comparing the provider's actual performance with the customers' general expectations of how providers in that industry should perform. More specifically, customers' satisfaction is mainly determined by their experience with the service provider; users' experience in turn is their perception based on their experienced service encounters. Empirical studies affirm the fundamental role of the service encounters in evaluating the overall quality and satisfaction with services (Parasuraman et al., (1985) (1988); Bitner et al., (1990). Significant research on the service profit chain has indeed revealed the changing, complex, cascading, and highly correlated relationships among job satisfaction, customer satisfaction and loyalty, and business profitability in service firms (Bolton and Drew, (1991); Heskett et al., (1994); Zeithaml, (2000); Lovelock and Wirtz, (2007); Gracia et al., (2010). In other words, the service profit (or value) chain for a service provider relies on the creation of loyal customers through experiencing excellent service encounters (Figure 3.10).

Figure 3.10 The service organizational profit chain with a focus on service encounters.

This new and emerging field is truly interdisciplinary in nature, and explores new frontiers of research in the service research arena. As this book's attempt is to establish the foundation for understanding of future competitiveness in services, we must have a new viable approach by taking a new and innovative path to study services. In manufacturing, products are central to both manufacturers and customers. When we trace the lifecycle of products, we can essentially analyze and understand how the manufacturing businesses have been operated (Qiu and Joshi, (1999). By the same token, service encounters are central to providers and customers in service businesses. Therefore, if we can trace the lifecycle of services, we can also analyze and understand how the service businesses have been operated. Ultimately, if we can track and understand service encounters well, we then have opportunities to develop and manage service businesses as desired.

To identify and develop a new approach to explore the science of service, surely it is wise for us to recapture what we have discussed and concluded so far in this chapter. By doing so, we can ensure that the direction of our proposed approach can be articulated in a profound and comprehensive manner. Here comes a list of our understandings of services and service systems in today and the future's globalized service-led economy:

- Sociotechnical Perspective. A service organization that offers and delivers services is essentially and holistically functioning as a service system. Truly, physical goods are the conduits of service provision. We understand that human and social capitals play an essential role in service provision. Therefore, we have to develop and manage efficient, effective, and smart operations of an integrated and collaborated sociotechnical service system that human and social capitals can be fully leveraged in service provision (Figure 3.9).

- Interactive–cocreative Perspective. Indeed, service provider-side and customer-side people must interact and hence cocreate the value of service. In other words, service encounters are central to providers and customers in the process of service provision; the dynamics of service offering and delivering processes largely represents the systemic behaviors of service systems in service business (Figure 3.9).

- Service Encounter Network Perspective. When we look into service provision over its offering and delivering time horizon, we find that the inherently interactive and collaborative nature among service providers and customers highlights the dynamics of the service value delivery networks. Hence, the formed service encounter networks in service provision can be modeled to describe the processes of transformation of customer needs in service operations and management across the service value delivery networks. As a result, by analyzing the dynamics of service encounter networks, we can interpret and understand the dynamics of corresponding service systems (Figure 3.9).

- Holistic or Systemic Perspective. Across the lifecycle of service, the dynamics of service encounter networks substantively depends on how 8 Ps are managed from stage to stage, meeting changing needs under different business circumstances, such as marketing, operations and management, and delivery. In other words, the priority of an individual P within 8 Ps might shift from stage to stage throughout the service lifecycle. When a service is performed, its customer and provider interact with each other, directly or indirectly, consecutively or intermittently, physically or virtually, briefly or intensively, during the process of performing the service. Therefore, 8 Ps must be fully leveraged for optimal service outcomes. That is to say, it must be explored in a holistic or systemic perspective (Figure 3.10).

- Computational Thinking and Analytics Perspective. The intelligent connection of people, processes, data, and things makes possible capturing and abstracting of the behavioral dynamics of service encounter networks in a meaningful way so that the changing needs of service customers can be well analyzed and optimally aligned with the business objectives of service providers (Figure 3.10).

With the above-mentioned understandings, it becomes essential for us to adopt service-dominant thinking and technically leverage digitalization and intelligent connections to explore services and accordingly service systems. When we investigate a systemic approach to explore service science, it now becomes clear that we must take the following key concepts into our considerations:

- It must be process-driven and people-centric. Once again, service is a process of transformation of the customer's needs utilizing the operations' resources, in which dimensions of customer experience manifest themselves in the themes of a service encounter or service encounter chain. As compared to manufacturing, service is people-centric, which must be cocreated by customers and providers.

- It must be holistic. The holistic or systemic viewpoint focuses on the “big picture” and the long-range view of systems dynamics, looking at a service organization as a collection of domain systems that constitute a whole. The systematic view allows us to see how each and every service activities is operated. We analyze the efficiency and effectiveness of each activity and accordingly control and manage them in a decisive manner. By paying attention to the whole, a holistic perspective thus allows us to understand and orchestrate service encounters among business domains across the service lifecycle.

- It must utilize computational thinking. Computational thinking that fully leverages today's ubiquitous digitalized information, computing capability and computational power has evolved as an optimal way of solving problems, designing systems, and understanding human behavior. Computational thinking promotes qualitative and quantitative thinking in terms of abstractions, modeling, algorithms, and understanding the consequences of scale and adaptation, not only for reasons of efficiency and effectiveness but also for economic and social reasons.

3.6.2 A Systemic and Lifecycle Approach to Exploring Service

The prior lack of means to monitor and capture people's dynamics throughout the service lifecycle has prohibited us from gaining insights into the service encounter chains or networks. Promisingly, the rapid development of digitization and networking technologies has made possible the needed means and methods to change this. From all the previous discussions, we conclude that one of the approaches to the explorations of services can be oriented to service encounters. We also understand that the adopted approach should be process-driven, people-centric, and holistic, while leveraging computational thinking.

Now is surely the time for us to explore service science by rethinking service encounters and study those social and transactional interactions in a deeper and more sophisticated manner than ever before. Let us briefly discuss what we could and should explore to optimize the service profit chain from the perspective of a service lifecycle (Figure 3.10).

It is worth pointing out that the Agile Project Management (APM) Group Limited in United Kingdom has pioneered a lot of IT service management studies with a focus on quality, integrity, and the cultivation of international best practice for knowledge-based workers. By focusing on IT service management, the APM Group publishes Information Technology and Infrastructure Library (ITIL) that defines five phases of IT service lifecycle, service strategy, design, transition, operation, and continual service improvement (ITIL, (2011). ITIL essentially provides comprehensive guidelines throughout the phases for aligning IT services with the needs of business. Note that the defined phases and the provided corresponding guidelines, based on goods-dominant thinking, essentially are product-oriented. Surely they can be well applied to the development and management of information-enabled solution products through fully leveraging the fast advancement of computing and networking technologies. In the following discussion, we present a high level guideline for executing service business by referring to the defined phases and the provided corresponding guidelines in ITIL v3 (ITIL, (2011). However, evolving from goods-dominant thinking, we use service-dominant thinking to define the new guideline with a focus of the means and methods to trace, control, and manage service encounters throughout the service lifecycles.

At the market, discovery, and strategy process stage, a service provider must identify and discover the current needs and ongoing trends in its serving marketplaces (Rust et al., (2004), and correspondingly develop and prepare its strategic and operational resources for business execution. It is critical for the provider to understand its operational capability and how to utilize and develop its capability, and hence determine its innovative and competitive service portfolios. Innovation is the highest priority (Chesbrough, (2011a). The provider should leverage all the potential interactions with current or prospective customers to capture their utilitarian needs and understand what would impact their sociopsychological needs. In particular, a service provider must now take advantage of the big data that are amassed on online social networks because online social networks have given rise to a new breed of monitoring and analytical means and methods. By digging into while parsing the cacophony of voices and conversations to uncover actionable information relevant to the provider's service offerings, social-media-based analytics can be well applied at this stage to help reveal needs and patterns and identify trends in its designated and potential service marketplaces (Schaeffer, (2011).

To make sure that a provider can well execute the market, discovery, and strategy process stage of a service, the provider should have done at least the following tasks:

- Defining Service Value Propositions. The values of services to the provider and customers must be simultaneously defined using the appropriate marketing mindset; service utilities and warranties shall be clearly identified in a deliverable manner.

- Planning Supportive Service Resources. Resources and capabilities in support of service provision across all business domains shall be identified and planned, including internal business units and external service collaborators.

- Determining Value-Added Service Structures and Corresponding Operational Trajectories. the dynamics of service systems shall be analyzed and determined through designing service structures or delivery networks in support of desirable, viable, and competitive service value chains.

- Creating a Contingency Plan. This should cover a variety of areas, from resources, operations, to recoveries, across the service value chains.

To accomplish those fundamental tasks, the provider should look into all 8 Ps at this stage. However, “People,” “Product,” “Place,” and “Price” are the critical ones; they must be well understood, identified, and planned. “Partner” could be included as a critical P in the service mix if the third party would be involved in the service. “People,” including providers and customers, are central to this stage. It is critical to meld assurance and empathy items into the service ideas during a service conceiving process. Therefore, service encounters do occur at this stage. Positive customers' involvements and contributions to this stage foster the development of customer experience excellence, ultimately leading to a great success of the provider's service business.

At the design and development stage, a service provider focuses on the design and development of both the identified innovative service products and the means and capabilities of delivering the services. Goods as the necessary conduit of service provision might be identified or purchased. Both operant and operand resources (Vargo and Lusch, (2004) should be developed and made ready for service provision. Processes, policies, and documentation to meet current and future agreed service requirements must be well designed and developed. The utilitarian needs based on agreed service requirements vary with services. The specification for a given service should clearly, completely, and consistently describe its customers' benefit and warranty, how the service will be delivered and consumed, and what responsibilities the provider and customers have during its service provision.

To make sure that a provider can well execute the design and development process stage of a service, the provider should have completed at least the following tasks:

- Defining and Validating Service Specification. On the basis of the identified value proposition, detailed service specifications should be defined and validated. Service-level agreements in great detail are typically finalized at this stage. Service contracts with partners shall also be finalized if partners are essential to the service provision.

- Developing and Preparing the Resources. This is critical for the realization of service value proposition defined at the market, discovery, and strategy process stage. All needed resources, in particular, the needed social and human capitals (Lepak and Snell, (1999), should be developed and prepared. As compared to goods, those resources must be well prepared and developed for not only delivering the specified technical and functional attributes in the service specifications but also meeting the customers' dynamic behavioral needs in their sociopsychological dimensions during the period of service consumption.

- Defining Measurements and Metrics and Developing Corresponding Means for Collecting the Necessary Performance Data. Unless appropriate measurements and metrics are clearly defined, the performance of service provision can be hardly evaluated. Truly, essential tools to collect the necessary performance data can be hardly developed or acquired without well-defined measurements and metrics.

To have those fundamental tasks done at this stage, the provider should certainly look into all 8 Ps as usual. However, “People,” “Product,” and “Process” are the critical ones; operant resources, products, and processes must be well analyzed and developed. It is similar to the preceding stage; “Partner” could be included as a critical P in the service mix if the third party would be involved in the service. Validating customers' requirements is the key to having the next stage of a service rolled out successfully. Without question, employees are central to this stage. Therefore, service encounters must occur at this stage. Customers' involvements and contributions to this stage truly lays out a sound and solid foundation that helps deliver customer experience excellence.

At the delivery, operations, and monitoring stage, service providers understand that this stage of a service significantly manifests itself as service encounters (Chiba, (2012). To many customers, the encounter of a service or “moment of truth” frequently is the service in the customer's perspective (Bitner et al., (1990). In general, service providers and customers substantively cocreate the values to the customers during the stage of service delivery and operations. Service operations responsible for all aspects of delivering and managing the customer service needs over the specified service period. The delivery and operations should be well monitored and controlled to ensure that the promised service levels are fully met.

To make sure that a provider can well execute the delivery, operations, and monitoring stage of a service, the provider should have completed at least the following tasks:

- Educating the Customers. Customers play a critical role in the creation of service values. The provider should educate the customers by leveraging all the means available in today's information era. The effectiveness of service encounters highly depends on how much the customers know about the service and their competencies to consume the service when the service is offered.

- Delivering the Service. This is the interactive point at which the provider and the customers cocreate the service values. Customer experience with the service is mainly assessed through both the outcomes and processes of service deliveries in light of meeting customers' utilitarian and sociopsychological needs over the service lifespans in the customers' perspective.

- Managing and Facilitating the Service Consumption Process. As customer experience with a service is the perception of meeting customers' utilitarian and sociopsychological needs over the service lifespans, the service provider should make sure that all involved service encounters during this stage of the service are well managed and facilitated. Service encounters vary with the 8 Ps (i.e., service provision mix). Technically, socially, and psychologically, a personal, optimal, while viable service consumption process for a customer should be carried out.

- Monitoring the Service and Detecting Ongoing and Potential Service Problems. The process of cocreating the service should be fully monitored and all the relevant data are collected, so any issue with the delivery and operations can be analyzed. In particular, if ongoing unsatisfactory issues can be detected in a timely manner, promptly, recoverable actions could be taken to compensate the customers.

To have those fundamental tasks done at this stage, the provider should surely look into all 8 Ps once again. However, “People,” “Product,” “Place,” “Process,” and “Physical Evidence” are the critical ones; they must be well understood, identified, and managed and operated. “Partner” could be included as a critical P in the service provision mix if the third party would be involved in the service provision. As the service must be cocreated by both providers and customers, “People” are central to this stage of delivering the “moments of truth.” The ultimate goal of this stage is to turn one-time customer into a lifetime customer through managing and delivering excellent user experience.

At the optimization and improvement stage, essentially service providers focus on the continual alignment, adjustment, and innovation of the offered services to meet the changing customers' needs. The service providers must keep challenging themselves in improving the service quality on continual basis, enhancing customer experience through continual innovation, and increasing the values that customers and providers can cocreate with the services. Continual service optimization and improvement is the outcomes of improvement actions that are identified through predefined analysis and optimization modules. Performance data must be collected in a comprehensive and timely manner. For instance, leveraging service encounter networks and/or relevant social networks to uncover complains and weaknesses can help recover service failures more effective, increase customer satisfaction, improve the effectiveness of market research efforts, and foster open service innovations (Chesbrough, (2003); Chesbrough, (2011b). The ultimate business award for us as service providers will surely be that customers become our service innovators and advocates over time.

To make sure that a provider can well execute the optimization and improvement process stage of a service, the provider should have completed at least the following tasks:

- Understanding and Embracing a High Level Business Vision. Continuing to be fully engaged with both current and prospective customers is the key to understand the ongoing changes of the business environment in which the provider is. The provider should be vigilant and readily embrace for the changes and accordingly define and adjust its high level business vision. The business vision should be timely and well communicated across the organization.

- Verifying that Measurements and Metrics are Working So that the Current Situation Can be Truly Assessed. This is a critical step to ensure that the needs of customers were fully understood and defined measurements and metrics are appropriate for the needed assessments. Adjustments and changes should be made if needed.

- Determining the Priorities and Corresponding Plan for Improvement. On the basis of the assessments of provided services, the priorities for improvement can be identified. Furthermore, the identified changes from the updated high level business vision should be well considered in determining the priorities and corresponding plan for improvement.

- Ensuring that Actions for Improvement are Embedded into the Organization. As discussed earlier, a systemic approach is a must in delivering competitive services in today and the future's service-led economy. Therefore, the identified actions for improvement must be embedded into the organization to ensure an optimal outcome from the adopted improvement measures.

To have those fundamental tasks done at this stage, the provider should unexceptionally look into all 8 Ps as usual. However, “People,” “Place,” “Process,” and “Physical Evidence” are the critical ones; they must be well understood and analyzed. “Partner” could also be included as a critical P in the service mix if the third party would significantly contribute to the service. Without question, “People,” including providers and customers, are continuously centered at this stage. Customers' involvements and contributions to this stage foster the continual alignment, adjustment, and innovation of the offered services, ultimately leading to a great success of the provider's service business.

References

- Ahlquist, J., & Saagar, K. (2013). Comprehending the complete customer. Analytics—INFORMS Analytics Magazine, May/June, 36–50.

- Berman, S. (2012). Digital transformation: opportunities to create new business models. Strategy and Leadership, 40(2), 16–24.

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: the effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. Journal of Marketing, 54(2), 69–82.

- Bitner, M. J. (1992). Servicescapes: the impact of physical surroundings on customers and employees. Journal of Marketing, 56(2), 57–71.

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Mohr, L. A. (1994). Critical service encounters: the employee's viewpoint. The Journal of Marketing, 58, 95–106.

- Bitner, M. J., Booms, B. H., & Tetreault, M. S. (1990). The service encounter: diagnosing favorable and unfavorable incidents. The Journal of Marketing, 54, 71–84.

- Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., & Meuter, M. L. (2000). Technology infusion in service encounters. Journal of the Academy of marketing Science, 28(1), 138–149.

- Bitner, M. J., Faranda, W. T., Hubbert, A. R., & Zeithaml, V. A. (1997). Customer contributions and roles in service delivery. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 8(3), 193–205.

- Bolton, R. N., & Drew, J. H. (1991). A multistage model of customers' assessments of service quality and value. Journal of Consumer Research, 17(4), 375–384.

- Bradley, G. L., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Sparks, B. A., Jimmieson, N. L., & Zapf, D. (2010). Service encounter needs theory: a dyadic, psychosocial approach to understanding service encounters. Research on Emotion in Organizations, 6, 221–258.

- Chase, R. B. (1978). Where does the customer fit in a service operation? Harvard Business Review, 56(6), 137–142.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2001). Want to perfect your company's service? Use behavioral science. Harvard Business Review, 79(6), 78–85.

- Chase, R. B., & Dasu, S. (2008). Psychology of the Experience: The Missing link in Service Science. Service Science, Management and Engineering Education for the 21st Century, 35–40, eds. by B. Hefley and W. Murphy. US: Springer.

- Chase, R. B., & Erikson, W. (1989). The service factory. The Academy of Management Executive, 2(3), 191–196.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2003). Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2011a). Open Services Innovation: Rethinking Your Business to Grow and Compete in a New Era. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Chesbrough, H. W. (2011b). Bringing open innovation to services. MIT Sloan Management Review, 52(2), 85–90.

- Chiba, T. (2012). Service encounter model focused on customer benefits and satisfaction: reconsideration of psychological model (No. 2011-034). Keio/Kyoto Joint Global COE Program.

- Czepiel, J. A. (1990). Service encounters and service relationships: implications for research. Journal of Business Research, 20(1), 13–21.

- Czepiel, J. A., Solomon, M. R., & Surprenant, C. F. (1985). The Service Encounter: Managing Employee/Customer Interaction in Service Business. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Daskin, M. S. (2011). Service Science. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Dietrich, B., & Harrison, T. (2006). Serving the services industry. OR/MS Today, 33(3), 42–49.

- Drogseth, D. (2012). User experience management and business impact—a cornerstone for IT transformation. Enterprise Management Associates Research Report. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.enterprisemanagement.com/research/asset.php/2311/.

- Durvasula, S., Lysonski, S., & Mehta, S. C. (2005). Service encounters: the missing link between service quality perceptions and satisfaction. Journal of Applied Business Research, 21(3), 15–25.

- FftF. (2012). The five capitals model—a framework for sustainability. White Paper from Forum for the Future. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.forumforthefuture.org/.

- Gracia, E., Cifre, E., & Grau, R. (2010). Service quality: the key role of service climate and service behavior of boundary employee units. Group & Organization Management, 35(3), 276–298.

- Grönroos, C. (1994). From scientific management to service management: a management perspective for the age of service competition. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 5(1), 5–20.

- Heskett, J. L., Jones, T. O., Loveman, G. W., Sasser, W. E., & Schlesinger, L. A. (1994). Putting the service-profit chain to work. Harvard Business Review, 72(2), 164–174.

- Heskett, J. L., Sasser, W. E., & Hart, C. W. (1990). Service Breakthroughs: Changing the Rules of the Game. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Hilton, T., & Hughes, T. (2013). Co-production and self-service: the application of service-dominant logic. Journal of Marketing Management, 29(7/8), 861–881.

- Hsu, C. (2009). Service Science: Design for Scaling and Transformation. Singapore: World Scientific and Imperial College Press.

- IBM. (2004). Services Science: A New Academic Discipline? IBM Research.

- IBM Palisade Summit Report. (2006). Service Science Education for 21st Century. Palisades, NY: IBM.

- ITIL. (2011). Information Technology and Infrastructure Library. ITILv3. Retrieved Oct. 10, 2012 from http://www.itil-officialsite.com/AboutITIL/WhatisITIL.aspx.

- Karmarkar, U. (2004). Will you survive the services revolution? Harvard Business Review, 82(6), 100–107.

- Larson, R. (1989). OR/MS and the services industries. OR/MS Today, April, 12–18.

- Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (1999). The human resource architecture: towards a theory of human capital allocation and development. Academy of Management Review, 24(1), 31–48.

- Lepak, D. P., & Snell, S. A. (2002). Examining the human resource architecture: the relationships among human capital, employment, and human resource configurations. Journal of Management, 28(4), 517–543.

- Lloyd, A. E., & Luk, S. T. (2009). Interaction behaviors leading to comfort in the service encounter. Journal of Services Marketing, 25(3), 176–189.

- Löbler, H. (2013). Service-dominant networks: an evolution from the service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Service Management, 24(4), 4–4.

- Lovelock, C. H. (1983). Classifying services to gain strategic marketing insights. The Journal of Marketing, 47, 9-20.

- Lovelock, C. H., & Wirtz, J. (2007). Service Marketing: People, Technology, Strategy, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Lu, I. Y., Yang, C. Y., & Tseng, C. J. (2009). Push-pull interactive model of service innovation cycle-under the service encounter framework. African Journal of Business Management, 3(9), 433–442.

- Meyer, C., & Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding customer experience. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), 116–126.

- Morris, B., & Johnston, R. (1987). Dealing with inherent variability: the difference between manufacturing and service?. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 7(4), 13–22.

- Palmisano, S. (2008). A Smarter planet: instrumented, interconnected, intelligent. Retrieved on Dec. 17, 2008 at http://www.ibm.com/ibm/ideasfromibm/us/smartplanet/20081117/sjp_speech.shtml.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. The Journal of Marketing, 49(Fall), 41–50.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERQUAL: a multi-item scale for measuring customer perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.