Chapter 5

Things rarely turn out as expected

Despite our best efforts, there will always be surprises. This chapter talks about minimising the number and effect of surprises.

Questions

True or false?

- It’s okay to hide contingency in a plan if that’s the only way you can ensure it stays in.

- Risks are threats to your project or venture. In assessing a particular risk, one of the main factors to consider is the likelihood of the risk happening.

- In assessing a particular risk, one of the main factors to consider is the impact that risk will have if it should happen.

The rule

‘Life is full of surprises.’ There perhaps isn’t a week goes by that we don’t find ourselves either saying this or being reminded of how true it is. In a sense, a lot of the things we’ve talked about so far – rule 2, know what you’re trying to do; 3, there is always a sequence of events; 4, things don’t get done if people don’t do them – have been about trying to reduce the likelihood of these surprises happening. You can think of dance cards as a way of looking into the future and searching for surprises.

Despite our best efforts, however, there will always be surprises out there waiting for us. ‘If you don’t actively attack the risks [on your project],’ software authority Tom Gilb has written, ‘the risks will actively attack you.’ Sometimes I think we are like people walking through minefields. The tools we have described give us partial maps of the minefield, but we know that these maps are incomplete and that unknown mines still lie there waiting for us.

To deal with these mines, we need some tools, and we will describe two. The first is the use of contingency or padding or margin for error. This tool is the equivalent of wearing body armour as we pass through the minefield. We know the mines are there, we assume that it is going to be impossible to avoid stepping on some of them, so some of them will definitely explode. What we want to ensure, then, is that the explosions don’t kill us. This is not a stupid approach. Not dying is a laudable and worthwhile aim! Contingency is a reactive thing. When a surprise occurs, the contingency (we hope) enables us to deal with it.

However, we can also do a smarter thing. We can look out over the minefield and identify suspicious looking bumps in the ground or signs of digging and say that there is a fair likelihood that there is a mine in a certain place. Then, as we progress through the minefield, we can try to manage our progress as best we can to get past those particular mines. These mines may still go off – and then the contingency is there to save our bacon. Not only that, but we may also have taken specific additional measures to deal with specific mines. And if the mines don’t go off, then so much the better – our efforts will be repaid many times over in terms of the number of ‘firefights’ we don’t have to fight. This latter approach is called risk management.

These two tools – the use of contingency and risk management – are described in the next section. And as for the questions at the top of the chapter – you should have answered true to all three of them. Read on if you’re in any doubt.

How to

Contingency

It’s possible to make this whole discussion reasonably complicated. Bearing in mind rule 1, many things are simple, let’s see if we can avoid doing that. Therefore, rather than trying to get into an exhaustive discussion of contingency, let’s converge quickly on a few simple ideas.

The first is, as we have said already, it’s mandatory. It’s not that you’ll only have it on your more cushy undertakings and jettison it on those that are down to the wire, you must have it on every venture.

In mature industries, such as construction, manufacturing or film-making, contingency is a fact of life, the same way that raw materials or labour rates are facts of life. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for a lot of the high-tech or knowledge industries that are floating around at the moment. Here contingency tends to be viewed with the same kind of suspicion and loathing normally afforded to a dog turd on somebody’s shoe. Suspicion because somehow it’s felt that the people asking for the contingency are going to use it to take a paid holiday. Loathing because it’s seen as a way for people to take the easy way out, to ‘remove the creative tension’, to make things comfortable for themselves, to be cowards, to be sissies.

As a result of this bizarre view, the general tendency in such industries is to remove contingency whenever it’s sighted. Given that we have already said that you have got to have contingency in the plan, you need to be aware of this tendency and counteract it when it arises. There are two ways to do this:

- either put contingency explicitly into the plan and stop anyone from taking it out; or

- hide it in the plan so that they can’t find it.

There’s actually a third option, which is to put the contingency in explicitly and let them take it out. Then they have the satisfaction of taking it out and you still have it in. And, of course, if you managed to stop them from taking it out, you would have twice as much and you wouldn’t hear any arguments from me on that score.

Finally, how do you do it? Well, you can pad out the estimates, say, of budgets (i.e. make the budget bigger than you think you’ll need) or resources needed (say you’ll need more than you actually need or say you want to hold on to them for longer) or time needed (i.e. add extra time on to the project). There are some other ideas on this in the ‘Examples/Applications’ section later in the chapter.

Risk management

While there are lots of complicated approaches to risk management, here’s a simple one that gets the job done. First it identifies the issues, then it gives us a way of dealing with them over the life of the venture.

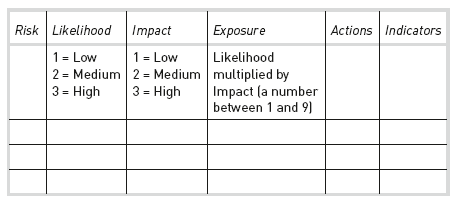

To manage risks we need to know a few things about them:

- which risks are likely to affect our undertaking;

- the likelihood of each of those risks happening;

- the impact of each of those risks happening;

- a calculation of our exposure to each risk so that we can deal with the major exposures;

- action(s) we can take to reduce our exposures;

- indicators, which will enable us to see if a particular risk has begun to materialise.

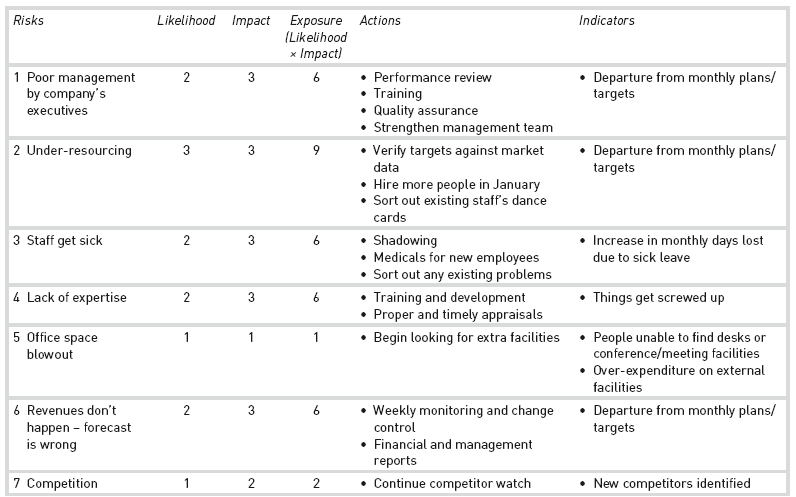

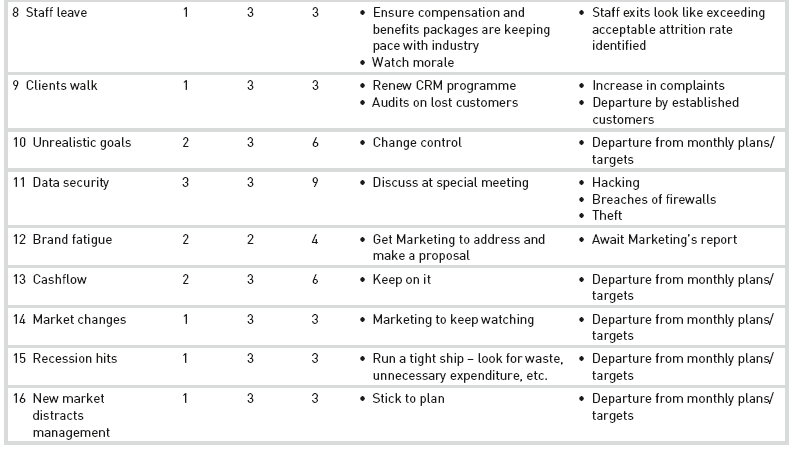

We will use Table 5.1 (overleaf) to record all of this. Using this table will enable us to see what the main risks are on our venture (risks with exposure 9 and 6 will be the ones we focus on). Then, on an ongoing basis, we can update Table 5.1 to give us our ‘top 10 risks’ list. Focusing regularly (say, weekly) on these will ensure that we stay on top of the scary things as our venture unfolds.

Just as with estimating a project, risk analysis is best done by the people who are going to have to carry out that project. So get them together. Ask them to brainstorm all of the things they can think of that could go wrong on the project. (Notice that once you have done this once, you have a set of risks that can be your start point when you come to do risk analysis on any future projects.) Write these risks in the first column of your risk analysis form (Table 5.1). Now get the team to grade the risks according to their Likelihood – these go in the second column. Then their Impact – into the third column. The Exposure column will then show you the major risks to the project.

Table 5.1 Risk management form

Now focus on these. What would be the signs that these threats to your project were beginning to happen? Write these in the rightmost column. Finally, what actions can you take to deal with these risks? These go into the Actions column. Example 4 shows a complete risk analysis.

Examples/Applications

Example 1 Incremental delivery

Some projects can be thought of as ‘all or nothing’ projects. Either everything has to be delivered/work – or it doesn’t. The big bang. The Y2K problem or the changeover (for those countries that did it) to the Euro are examples of such projects. But such projects are inherently high risk, because if the big day comes and nothing works, then you’re sunk.

So to avoid this situation, see if you can roll out the project in a series of deliveries or increments. If you have to deploy something in seven locations, for example, don’t try to do all seven of them together. Do one first. Learn from it. Make your mistakes. Then maybe do two more and then, finally, the remainder. Or think in terms of have-to-have and nice-to-have. Give them the have-to-haves first and then roll out the nice-to-haves after that. I hope you can see it’s a way of putting contingency in your plan. And it’s a way that stakeholders like. Stakeholders hate the big bang – it scares them.

Here’s an interesting example of doing this that I came across recently. A woman on one of my courses worked for an organisation that set up women’s refuges. Her job was to set up three in a certain area. Her initial idea was to run the three projects to set up the three refuges in parallel. They would run together and finish at the same time. But she quickly realised that one of the biggest threats to all this was – as it is for many not-for-profit organisations – a budget cut. What if the funding was cut as she was part way through the three projects? So what she decided to do instead was to run one project and try to get it over the line. She would learn from this one and then she would run the other two in parallel. Even if the funding was cut, she had the possibility of ending up with something rather than nothing.

Example 2 Under-promise and over-deliver

If you can build incremental delivery into your project then it raises the possibility of under-promising and over-delivering. Say you’ve identified that it would be possible to do three deliveries thus:

| Delivery 1 | July 31 |

| Delivery 2 | August 15 |

| Delivery 3 | August 31 |

Instead of telling your stakeholders this, promise them, for example:

| Delivery 1 | August 15 |

| Delivery 2 | August 31 |

| Delivery 3 | September 15 |

Now, if you can deliver to the original schedule, they’ll love you. The Chilean mine rescue in 2010 was a stunning example of under-promise and over-deliver. In August when it was realised that the 33 miners were alive, it was said that it could take until Christmas to get them out. The miners were actually lifted to the surface over 12–13 October.

Example 3 Why contingency is mandatory

In Chapter 2, we talked about healthy and unhealthy projects and the three possible ways of dealing with changes. If you don’t have contingency in your plan, because either:

- you didn’t put it in in the first place; or

- you did, but then some genius took it out and you didn’t stop them,

then you lose one of your three possible responses to changes. What this means in reality is that every change which occurs on your project which is not a big change will have to be dealt with by sucking it up, i.e. by working more hours. An unhealthy project? You betcha!

Example 4 Risk analysis for a company’s business plan

Table 5.2 overleaf illustrates a risk analysis of a company’s business plan. You will see from some of the risks (e.g. the first one) that the people who did it are being brutally honest. This obviously makes for the best kind of risk analysis!

This template also shows how easy it is to complete a risk analysis. Given the things it could potentially uncover, the 20 minutes or half-hour you spend doing a risk analysis could turn out to be one of the best investments of time you’ve ever made.

AND SO, WHAT SHOULD YOU DO?

- Add contingency into all of your plans using the techniques we described in the ‘How to’ section.

- Do risk analyses on all of your plans.

- Maintain a ‘top 10 risks’ list and review it on a regular (weekly, monthly) basis.