Chapter 7

Look at things from others’ points of view

In Chapter 1, we talked of seeing things simply. One simple way of seeing things is to see them from other people’s points of view. Almost everything we undertake involves other people. Seeing things as they see them can be a powerful aid to understanding and getting things done.

Question

You’ve joined a new organisation and you’ve discovered that one of the people who works for you appears to be seriously overpaid for what he does. You know that he is pretty settled and happy in the organisation. You know also that he’s fairly reasonable. You decide to reduce his salary to that of his peers. Your analysis is that while he might be very upset about it initially, he will eventually see your point of view and the whole thing will blow over. Is this what actually happens?

(a) Yes, it’s all about how settled and happy he is in the organisation. That plus the fact that he’s a reasonable person.

(b) He goes ballistic. He quits and you end up with a lawsuit on your hands.

(c) It’s stormier than you had expected. You have to give a bit and not implement as big a reduction as you had been planning. Then it passes.

(d) You sleep on it, wake up the next day and decide this was a crazy idea. You’ve got plenty on your plate without drawing this on yourself. You let sleeping dogs lie.

The rule

First, the question. If you think that anything other than answer (b) is the right answer, you need to spend more time empathising with people.

The final rule is a very old one. Interestingly, it is also common to a number of the world’s major religions.

For example, you may know of the Talmud, the 20-volume work that can be thought of as an ‘encyclopaedia’ of Judaism. The Talmud tells the story of a Gentile who comes to a Rabbi and asks to be taught all of Judaism while standing on one foot. One of the Rabbi’s students has the man driven from the Rabbi’s door, taking the question to be impertinent or mocking. Unperturbed, the Rabbi replies: ‘What is offensive to you do not do to others. That is the core of Judaism. The rest is commentary. Now carry on your studies.’

Buddhism also has a view on this rule. Here is the Dalai Lama on the subject: ‘I think that empathy is important not only as a means of enhancing compassion, but I think that generally speaking, when dealing with others on any level, if you’re having some difficulties, it’s extremely helpful to be able to try to put yourself in the other person’s place and see how you would react to the situation.’

Finally, the notion of ‘do as you would be done to’ is one that is widely known in the Christian faith.

The six rules we have looked at so far are very much about getting things done. More than anything else, the thing that will determine how easy or difficult things are to get done will be how people react to them. If people are positive and well motivated, they will move mountains. On the other hand, if people are not well disposed towards what is being attempted, they will, in an extreme case, bring it to a halt.

The rule, then, is simple. See things from other people’s viewpoints and modify your plans and/or behaviour, if necessary, to maximise your chances of success. Precisely how you do this is the subject of the next section.

How to

Put yourself in their shoes

Once again, we can quote the Dalai Lama who describes this technique very simply and elegantly. He says: ‘This technique involves the capacity to temporarily suspend insisting on your own viewpoint but rather to look from the other person’s perspective, to imagine what would be the situation if you were in his shoes, how you would deal with this. This helps you develop an awareness and respect for another’s feelings, which is an important factor in reducing conflicts and problems with other people.’

My editor, Rachael Stock, has put it another way, but no less eloquently: ‘Never assume you know everything.’ Or to put it another way still: ‘Be open to learning from others.’ Finally, the point is also made by Stephen Covey in his bestselling The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. One of Covey’s ‘7 habits’ is to ‘think win/win’.

Maximise the win-conditions of the stakeholders

We saw this concept in Chapter 2, when we looked at the ‘know if what you’re trying to do is what everyone wants’ tool. Just to remind you, the stakeholders are all those people affected by what you’re intending to do. Each of those stakeholders will have a set of win-conditions. Win-conditions are those things that they want to get from the particular venture or undertaking. It is quite likely that the various win-conditions will not be compatible with one another. Anyone who has even a nodding acquaintance with the peace talks in Northern Ireland or in the Middle East should have no problem understanding this concept. So, given that the various win-conditions are often more or less incompatible, this tool is about trying to find a set of win-conditions that everyone can live with. You’ll remember we described a way of doing this in Chapter 2, Example 1.

Examples/Applications

Example 1 Meetings revisited

Using all of our rules, we can now see how to conduct a decent meeting. We can also use our rules to spot when we’ve been landed with a turkey – a meeting that will consume everybody’s time and be of little value, if any.

To conduct a meeting, you need to do the following:

- Figure out the objective(s) of the meeting (rule 2, know what you’re trying to do).

- Identify the bunch of things that have to get done to get you to the objective(s) (rule 3, there is always a sequence of events).

- Identify who should attend. People are going to have to do those things (rule 4, things don’t get done if people don’t do them). Thus rules 3 and 4 identify who’s got to come to the meeting.

- Build the agenda. Rules 3 and 4 also enable us to build the agenda, including a time constraint on each item. Using rule 5, things rarely turn out as expected, add in some contingency to give the time constraint on the meeting as a whole.

- Publish the objective(s), agenda and time constraints, and indicate to each participant what preparation, if any, is required from them (rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view).

- Hold the meeting, driving it to the agenda and time constraints you have identified (rule 4, things don’t get done if people don’t do them).

- Prepare an action list arising from the meeting (rule 3, there is always a sequence of events).

- Stop when the time is up. By then, if you’ve done your job properly, the objective(s) should have been met.

To spot a turkey, do the following. When you are asked to come to a meeting, ask:

- What is the objective?

- Why do you need to go? In other words, what leads them to believe that you can contribute anything useful?

- What preparation do you have to do?

- How long will it last?

If you can’t get sensible answers to all of these questions, you’re probably on to a loser. Assuming you’re a person who espouses the virtues of common sense then you should simply not go. If you wanted to pass on that common sense to the other people, you could write an email explaining why.

Example 2 Status reporting

In status reporting there seem to be two schools of thought: tell ’em nothing and tell ’em everything. Interestingly, the two schools have something in common – both types of report can result in you not getting any information at all on the status of things. In the first case, this is because they didn’t actually give you any, while in the second, it’s because they overwhelmed you with so much stuff that it’s impossible to see the wood for the trees. Rule 7 tells us that we have to tell others what we’re doing. It doesn’t say we must tell everybody 100 per cent of everything, but it does say that we can’t tell them nothing.

Now if we’re not going to tell 100 per cent, what are we going to do? Well, we must filter what we’re saying in some way, but not so much that the message is garbled, misunderstood, hidden, reversed or lied about. In my experience, the majority of traditional status reports, whether written or verbal, do all of these things. In general, such status reports give the impression that there are impressive amounts of stuff happening – we did this, we did that, this happened, that happened. (The message is: ‘We’re earning our money.’) Not everything that happens is good stuff, so status reports are always keen to report bad incidents that have occurred. (The message is: ‘We’re really earning our money.’) But there’s always the almost compulsory happy ending, the feeling that in spite of everything, we’re going to be OK. In other words, few status reports are prepared to report bad news.

In general, people are interested in one or more of the following aspects of what you’re doing:

- Will I get everything I thought I was going to get and, if not, what can I expect?

- Is it on time and, if not, what can I now expect?

- How’s it doing as regards costs – Over? Under? About right?

- Will the thing I get meet my needs?

In reporting the status, you need to tell them about the things they are interested in. And you need to tell them both the instantaneous status – here’s how it is today – and what the status is over time – in other words, the trend. Only then can they have a true picture of how things are going. By truthfully reporting the trend, they can understand not just the kind of shape we’re in today but also how things might unfold in the future. The result will be no surprises in store for anybody.

Finally, who are we talking about here? Well, all of the stakeholders, as we’ve defined them earlier. In general, there are at least four that we can always regard as being present. The first is you, the person responsible for getting the thing done; next is your team, the people who are doing the work; third is the customer, for whom the work is being done; and finally, your boss. All of these need to be given an insight – though not necessarily the same one – into how things are proceeding.

First, you need to understand that status yourself. Rule 6, things either are or they aren’t, will help you here. Once you know, by considering the status from other people’s points of view (rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view), you will be able to deliver the status to them. It will be a message that they can understand (because it is expressed in terms that are real to them), that gives the status (because it tells the truth) and that will seek to clarify rather than obscure how things are going.

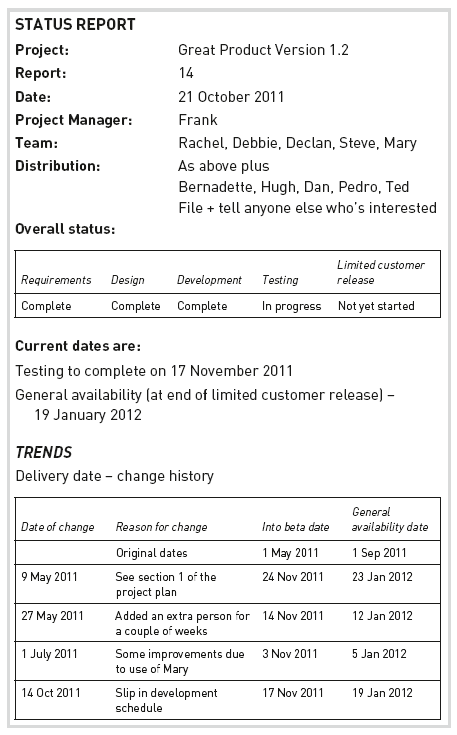

Table 7.1 opposite gives an example of some extracts from a status report. The extracts illustrate both instantaneous status and one possible trend we might be interested in.

Example 3 Some stress management techniques

Keep a sense of proportion (or, there is always someone worse off than you)

This one comes to us courtesy of the ‘are things better or worse?’ tool in Chapter 6. In general, no matter how bleak your situation may be, it is almost certainly true that there is someone in the world worse off than you. Every day, thousands of people die of hunger, disease, torture, execution, neglect, abuse, loneliness. Most of the things we face don’t add up to a hill of beans in the context of these problems. The next time you’re feeling stressed, pick up the paper or turn on the television news.

See it a year from now

Rule 7 tells us to look at things from others’ points of view. Imagine yourself a year from now. How will the issue that is causing you so much worry seem a year from now? Will you actually be able to remember it? Visualise it and see if this brings anything new.

The marathon runner

I used to run marathons (not very well, I should add). Now I think you’ll agree that the notion of running 26 and a bit miles is ridiculous. It’s outrageous. And so, rather than thinking about all the appalling stuff that lies up ahead, marathon runners use – whether they know it or not – rule 3, there is always a sequence of events. Don’t worry about the stuff that lies way off in the future. Rather, work your way through the next little job in the sequence. In the case of marathon runners, this means making the next telegraph pole, or tree, or mile marker or feeding station. Then turn your attention to the next stage of the journey.

Talk to somebody

Rule 7 again. Also, as the old saying goes, ‘A problem shared is a problem halved.’

Example 4 Assessing things – projects and project plans

Increasingly, one of the things you may be required to do is to assess plans that are being proposed or undertakings that are actually in progress. For example, a subcontractor may be presenting a plan for something that has been outsourced to them. Or you may be asked to make a recommendation on a business plan or the proposed funding of a particular venture. Or the venture may already be in progress and the question is how well or otherwise it is doing. Often these days, these things we are being asked to make a decision on are highly technical or complex, and we may not be personally familiar with the technicalities or complexities. How, then, do we make the right decision? Our rules of common sense can help us chart a way through the mass of data and unearth the nuggets of information we really need.

It seems to me that sometimes people refer to this as ‘gut feel’ or ‘gut instinct’. Gut feel is not a wild stab in the dark but a sense or a feeling that the odds are in your favour. The following is a way of trying to assess those odds.

Imagine you are at a presentation about, or reading a report on, or considering some venture that is occurring on the ground. What do you need to look for?

- Rule 2, know what you’re trying to do, tells us that somewhere in the welter of information there had better be some sort of goal or objective to this thing. This goal must have two main characteristics. First, it must be well defined, i.e. it should be possible to tell, quite unambiguously, when this goal will have been achieved. There should be no confusion or fuzziness about whether or not we will have crossed the finish line. For example, confusion among the stakeholders as to what constituted the end would be a classic breach of this requirement. The other thing is that the goal must be current, i.e. any changes to it that have occurred along the way should have been accumulated and now be part of the final goal.

- Rule 3, there is always a sequence of events, says that somewhere we should be able to see the series of activities that bring us through the project from where we are now to the goal. This sequence of events could be represented in many forms, and we have seen some of them in this book:

- The level of detail of the sequence of events must be such as to convince us that somebody has analysed, in so far as they can, all the things that need to be done in this project. Pretty, computer-generated, high-level charts don’t cut the mustard – unless they can show you the supporting detail.

- Rule 4, things don’t get done if people don’t do them, says that there had better be someone leading the venture, and all of the jobs in the sequence of events better have people’s names against them. Also, people’s availability must be clear. Names aren’t enough. We need to know how much of those people’s time is available to work on this venture. Notice that with points (2) and (3) it should be possible to do a quick calculation that will test the venture to its core. Point (2) should tell you how much work has to be done, (3) should tell you how much work is available, i.e. how many people for how much of their time. These two numbers should essentially be the same.

- Rule 5, things rarely turn out as expected. If the venture has no contingency or margin for error in it, send them home with a flea in their ear!

Example 5 Build a fast-growing company

In the 6 September 1999 edition of Fortune, there was an article on America’s fastest growing companies. The article identified seven factors that these companies had in common. Perhaps, at this stage, it should come as no surprise to us that behind these seven factors we can clearly see our rules.

- The companies always deliver on their commitments (rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view). If somebody is a customer of yours then, despite the way it may seem at times, they don’t actually expect miracles. (No, really, it’s true!) What they do expect, and rightly so, is that you will deliver on whatever they have been led to believe and meet whatever expectations have been set for them.

- They don’t overpromise (rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view – again). This is really not too different from the preceding one. In the article, this factor was related specifically to what companies were promising to deliver – and subsequently did deliver – to the financial community/Wall Street.

- They sweat the small stuff (rule 3, there is always a sequence of events). If you remember, a lot of what we talked about in Chapter 3 was about trying to understand the detail of what needed to happen. These days, in a lot of cases, time is an even more valuable commodity than money. Knowing where our time goes, ensuring that it is spent wisely, removing time wasters, and avoiding having to firefight things which should never have been firefights in the first place, is what this one is all about.

- They build a fortress. This one is about protecting your business, especially by creating barriers to entry (rule 5, things rarely turn out as expected). Just because things are going well doesn’t mean they’ll always go well. Maintaining a healthy insecurity about things, always having some contingency in the bag and keeping a watchful eye on the top 10 risks will ensure that your fortress becomes as impregnable as possible to attack.

- They create a culture (rule 2, know what you’re trying to do). This factor is about the corporate cultures that these fast-growth companies have created. In all of the cases cited, the companies set out deliberately to create a certain kind of culture, be it a very formal one, as in the case of Siebel Systems, or an informal one like casual-clothes maker, American Eagle.

- They learn from their mistakes (rule 3, there is always a sequence of events/record of what actually happens).

- They shape their story. This again is about ensuring that the investors/financial analysts never feel uncertain about a company, but rather are kept in the loop by the company as to what is going on. Again it’s about rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view. As the article says: ‘When there is uncertainty with this kind of small, growing company, the first thing people do is run … And when one money manager sees someone else bailing out, his first thought is: “What does that guy know that I don’t?” They don’t wait around to find out what’s really going on.’

Example 6 Presentations

You know how busy you are. Everyone else is that busy too – never enough time and so many things to be done. Now, if people are going to give up some of their incredibly scarce time to come and listen to something you say, then you damn well better make sure it’s worth listening to.

I don’t know how you’ve found it, but in my experience good presentations are something of a rarity. Instead I’ve seen plenty of presenters and presentations that were any of: smug, patronising, aggressive, incomprehensible, unconvincing, rambling, scared, verbose, ran on too long, bored the audience silly, too casual, dishonest, or unsure of their material. The presenter who is authoritative, interesting, relaxed, maybe humorous or dramatic, who believes in what they say, and who communicates that belief, is still something of an oasis in the desert when you come across them.

While you’ll always learn something useful at them, you don’t have to have attended umpteen presentation skills courses to be a good presenter. Common sense shows you what you have to do to make a good presentation.

- Rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view, starts us in the right place. People are going to give up their time to come to this presentation. Why is that going to be a useful thing for them to do? Presumably they’re going to learn something that is to their advantage. But, you may say, I’m making a sales presentation, I’m trying to sell them, something, not educate them. Uh-uh, I don’t think so. I make sales presentations all the time. And the best ones are those where I set out to teach my audience something and then, somewhere in the midst of it all, put in the sales messages. How many pure sales presentations have you been to that you remember? Okay, so this is the first point: you’re going to tell them something that is to their advantage. If at all possible, ask members of the audience some time in advance of the presentation what they are hoping to get from it. This obviously maximises the chances that you will actually give them that. You can do this right up to the moment you’re about to begin; however, the earlier you do it the more time you have to prepare.

- Rule 2, know what you’re trying to do. Okay, you’ve decided you’re going to tell them something to their advantage. Now you need to decide precisely what your main messages are. And since it is also well known that people can’t remember too many things, you’d better make sure that you have only a handful of main messages.

- Rule 3, there is always a sequence of events. Now decide the sequence in which you are going to tell them the messages. Research has shown that the human brain primarily remembers the following:

- items from the beginning of the learning period (‘the primacy effect’);

- items from the end of the learning period (‘the recency effect’);

- items which are emphasised as being in some way outstanding or unique.

Of course you didn’t need research to tell you this. It’s known through the great adage for all presenters:

- tell ’em what you’re gonna tell ’em;

- tell ’em;

- tell ’em what you told ’em.

Again, research has shown that people remember those items which are of particular interest to them, hence the value of understanding in advance what it is they want to know. This also tells us that we should try to present each of our points from a point of view that our listeners can relate to (rule 7, look at things from others’ points of view).

- Rule 5, things rarely turn out as expected. So anticipate the questions that might get asked. If you can’t, have a dry run – this will throw them up anyway. Questions can often take you down paths you hadn’t intended to go, and deliver messages you didn’t intend to deliver. A dry run will help you spot these trapdoors and close them. Questions also highlight points where your presentation is weak or prone to misunderstanding or is unclear, and so are invaluable in terms of improving the presentation next time you give it. That is, of course, if you view questions in this way – as a learning opportunity. Not everyone does!

- Now do it. Use the adage of ‘First things first’ to deliver your key messages at the beginning. Work your way through the rest of it. Then remind them of the key messages at the end.

AND SO, WHAT SHOULD YOU DO?

- When you are undertaking anything, remember that in almost all cases, other people will be affected by what you do. See if you can ensure that you identify who those people are, what their views and needs are, and how much you can take these into account.

- If at all possible, when planning something, try to involve the people who will do the work.