3

The Emotional Skills of Police Officers in the French Anti-crime Squad (BAC)

In certain professions, emotions, shaped by social rules governing our behavior, must be controlled (Hochschild, 1983/2003). Service professions are therefore the most concerned by research on the regulations of emotions at work. Contact with the general public encountered, in certain professions, can be quite tricky to manage and constitutes a factor of psychosocial risk (PSR). This is the case of police officers of the brigade anti-criminalité (French anti-crime squad), BAC. For these professionals, as first responders on public roads, work and health interact, their activity representing “the place of integration of work and health constraints” (Laville, 1998, p. 153). Beyond this issue of professional health, the influence of emotions at work, generated by the physical and psychological risks which are remarkably significant in extreme environments, on organizational performance, the quality of interventions and the work collective, raises questions. In order to provide some answers, the specific context of the BAC was studied, in the framework of qualitative research, combining an ethnographic approach through participatory immersion, with semi-directive and non-directive interviews with 20 professionals in the field, their managers and the professionals concerned with police officers’ occupational health issues, and the elements of secondary, managerial and human resources management (HRM) documentation.

3.1. Police activity: emotions

3.1.1. First intervention on public roads: a psychosocial risk

The framework agreement of October 22, 2013, relating to the prevention of psychosocial risks (PSRs) in the public service in France, required each public employer to develop an evaluation and prevention plan of PSR for the year 2015. PSR, the risks estimated by individuals on a situation and their ability to manage it (Lancry et al., 2008), corresponds to the risks for mental, physical and social health, generated by working conditions as well as organizational and relational factors interfering with the mental functioning of the individual. Incivilities, assaults and the violence of the public, experienced in work situations, generate emotions, relating to fear and anxiety, anger, disgust, surprise, etc. When they are unpleasant, chronic and/or evaluated as unacceptable by professionals, these emotions can give rise to different manifestations affecting the physical or mental health of individuals: occupational stress, malaise, suffering, psychosomatization, decompensation and even burnout. The emotional component at work fundamentally integrates in the current theme of PSR prevention. The individual will favor certain emotional responses in order to maintain control of the situation (Lazarus, 1999).

PSR represents risks that can be induced by the activity itself and/or generated by the organization and work relations. Gollac and Bodier (2011), in their report requested by the Ministry of Labor, Employment and Health (Ministère du travail, de l’emploi et de la santé), count six PSR factors: intensity and working time, emotional demands, autonomy and room for maneuver, social and work relations, conflicts of value and socioeconomic insecurity. These six factors relate to the emotional component at work: “As in any other area of human activity, work is the scene of the (re)production of different emotions: we fear of having an accident, of falling sick because of work, or of losing our employment; we are satisfied and proud of a job well done, we are angry when faced with an injustice at work” (Soares, 2000, p. 2).

Emotional labor, theorized by Arlie Hochschild (1983/2003), a dynamic self-regulation process, corresponds to the “conscious, intentional attempt to modify one’s feelings”, an act “which aims to evoke or shape, or equally to suppress a feeling”; the term “feeling” seems for the author to be interchangeable with that of “emotion” (Hochschild, 2003, p. 32). The concept of emotional labor coincides with the risk factor “emotional requirements”, the latter being “related to the need to master and shape one’s own emotions, in particular in order to master and shape those felt by the people with whom one interacts at work. Having to hide one’s emotions is also demanding” (Gollac and Bodier, 2011, p. 15). According to the survey Santé et itinéraires professionnels (Dares, 2007), these requirements include several dimensions. Being “always” or “often” exposed to “verbal attacks, insults, threats” and physical assaults corresponds to an emotional requirement. Another type of emotional requirement is having to “calm people” and “be in contact with people in a situation of distress” during work (Dares, 2014). This also includes having to hide one’s emotions at work (Dares, 2007). Finally, fear is an emotional requirement (Gollac and Bodier, 2011) when it comes to the fear of violent acts, leading the individual to deploy a particular vigilance; the fear of making mistakes; the fear of an accident and violence; and the fear of not doing a “good job”. These states of fear amplify the risks of mood and anxiety disorders.

Contact with the general public engages emotions in the professional context: this is the case for the police officers on public roads (Loriol and Caroly, 2008), first responders. The relationship with the general public, called “first contact”, for the police officers of the anti-crime squad (BAC), sometimes has consequences on the health of the professional, due to the emotional dissonance felt resulting from emotional work and great emotional and psychosocial requirements.

3.1.2. Emotions at work

Relationships at work involve emotions. Emotion is generated by an object or an event (Lazarus, 1991) and includes five components: cognition, physiology, motor expression, action tendencies and subjective feeling (Scherer, 2000). The organism responds to the evaluation of an internal or external stimulus (Scherer, 2000, p. 139). Emotion allows individuals to adapt to their environment. It is triggered by physical and physiological factors. Emotions correspond to “organized responses, crossing the boundaries of many psychological subsystems, including the physiological, cognitive, motivational and experiential systems” (Salovey and Mayer, 1990, p. 186). In fact, these are “complex states of the organism which involve body changes (…) and at the mental level, a state of excitation or disturbance, marked by a deep feeling and usually an impulse leading to a definitive form of behavior” (Lazarus, 1991, p. 36).

According to the appraisal theory – a cognitive evaluation theory – each individual cognitively evaluates a situation, its relevance in relation to his or her well-being and the possibility of controlling the consequences of the event. This cognitive evaluation determines the emotion felt (Frijda, 1986; Scherer, 2001). Weiss and Cropanzano’s (1996) theory on emotional events – the affective events theory – specifies that the events experienced and interpreted by individuals cause emotions. There is a primary evaluation of the event in relation to the individual’s well-being and then a secondary evaluation, related to the control of these consequences. This approach involves individual emotional dispositions and exogenous demands on the work environment. The individual’s behavior is related to the frequency of a type of emotional feeling, rather than its intensity (Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996).

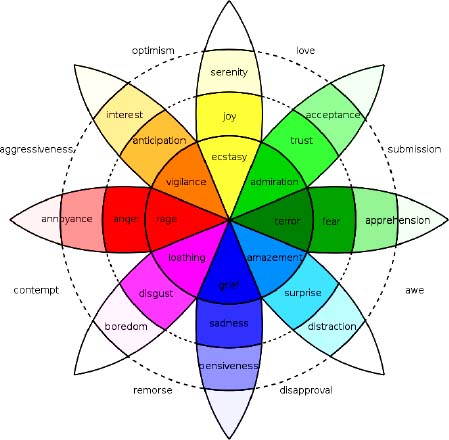

Plutchik (1980, 2001) has listed, in the form of a three-dimensional circumplex model, 24 emotions, in eight branches of three emotions of variable intensity. Vigilance, ecstasy, admiration, terror, astonishment, sorrow, aversion and rage are the eight emotional states of greater intensity.

Figure 3.1. Plutchik’s multidimensional model (Wikipedia, 2018). For a color version of this figure, see www.iste.co.uk/roger/skills.zip

The emotional component at work has long been neglected in the theories of organizations, up to the branch of human relations that implies the impact of emotions at work on productivity and well-being at work (Mayo, 1945; Likert, 1967). Despite this implicit reference to the role of emotions at work, they have been squeezed out of the organization by Taylorism and bureaucracy. Researchers began to address the issue of emotions at work in the 1980s (Hochschild, 1983/2003; Rafaeli and Sutton, 1987; Eiglier and Langeard, 1987). Little by little, disciplines related to work activity have integrated the emotional factor in their research. HRM, concerned with health, quality and performance issues, has every interest to take into account this emotional aspect at work and especially to integrate the theme of emotional skills, real work tools of service professions who are in first contact with the general public. In relational professions, emotions must be controlled, repressed, aroused and regulated (Hochschild, 2003). Service professions are therefore the most concerned with research on the management of emotions at work. Contact with the general public encountered, in certain professions, can be quite tricky to manage. This is the case for BAC police officers.

3.1.3. BAC police officers

BAC, a specialized service of the French national police force, was created in 1994 and reports to the Central Directorate of Public Security (Direction centrale de la sécurité publique – DCSP). BAC police officers usually serve in civilian clothes with a “Police” armband. They wear a bullet-proof vest and have individual and collective weapons. Specialized in sensitive environments and priority areas, they circulate most of the time in patrols of three to four officers, in unmarked vehicles. On certain cases, they can group together in larger groups. The recruited police officers have already completed a few years of service, because “police” experience makes it possible, according to them, to manage more at-risk situations. The core of their profession, flagrante delicto, searching for offenses and crimes and interventions on requisitions, integrates in to an environment full of uncertainties, surprises and possible violence. The main role of the BAC is to maintain order throughout the territory, particularly in sensitive neighborhoods, and to fight against small and average delinquencies. The main missions of these police officers are to fight against all types of crimes and offenses, maintain and, as appropriate, restore peace and order, and intervene to put an end to urban violence.

This study on the emotional skills of police officers on public roads in a specialized service of a large conurbation concerns, on the one hand, a profession frequently exposed to physical and psychological risks (Monjardet, 1996). BAC police officers daily come into contact with a number of “suspects”: dangerous, hostile, unpredictable, sometimes with psychiatric problems, becoming “the persons involved” (mise en cause) or “arrested” in cases where arrest is required, and/or a number of “victims”: in distress, panicking, having or not having suffered violence or theft. On the other hand, this research is part of a context of insecurity and serious international terrorist danger, with a state of emergency having been maintained in France from November 14, 2015, to November 1, 2017. For example, the first two responders to the terrorist event of November 13, 2015, in the Bataclan (Paris) were BAC police officers. These police officers, during their intervention, tried to regulate, on the one hand, their own emotions in the face of the situation, and, on the other hand, the emotions of the then present victims, while proceeding to take action in a professional manner: “I was surprised myself: I was perfectly serene. I think that the experience gained in my duties at BAC, where we are regularly confronted with difficult situations, and our regular meetings at the shooting range, allowed me, at that moment, to manage my stress” (reflection at France’s national police college, from a BAC superintendent, a first responder in the Bataclan. This refers to the time when the police officer pointed his gun at the terrorist).

Regarding the management of emotions in the work context, this profession also offers a real case study of a risky activity in first intervention. In this profession with strong emotional demands, police officers’ emotional skills are informally taken into account during recruitment, during post-intervention debriefings and during exchanges between police officers during the activity. No tool of human resources management (HRM) expressly and formally addresses the emotional skills that the profession requires, or the emotional demands that it contains. Technical and general training approaches this consideration of emotions in a real work context and sometimes allows police officers to develop skills related to the regulation of emotions at work, but the analysis and processing of the emotional aspect in intervention remain implicit. The annual skill assessment formally takes police officers’ behavioral and emotional aspects into account, but in a limited and channeled way.

3.2. The work of emotion: police officers’ emotional skills

3.2.1. From emotions to BAC police officers’ emotional skills

The term “emotional skills” seems functional in the cases studied, in the sense that the regulations of emotions are examined in their concrete applications at work. Competence is fundamentally contextualized, as it depends on the characteristics or requirements of a work situation. Two aspects of competence are raised: individual and work situation, competence manifested at the intersection between individual and specific characteristics at the work situation (Everaere, 2000). The emotional skill that is mentioned in this research is put into place: “Competence is a practical intelligence of situations which is based on acquired knowledge and transforms them with all the more force as the diversity of situations increases” (Zarifian, 1999, p. 70).

In work situations, the individual can mobilize four types of mental operations: motivation, emotions, cognition and awareness (Salovey and Mayer, 1997). Emotions indicate and warn about changes, real or otherwise, concerning the relations between individuals and their environment: for example, fear is a response to danger, anger to threat. The external changes or the perception of these changes by the individual cause the emotion. Emotions organize several basic behavioral responses concerning the relationship between people and their environment. Cognitions allow people to solve problems related to their environment and to learn.

Figure 3.2 illustrates the interaction between the two mental operations, cognition and emotion, leading people to adapt their behavior to the situation. During an emotionally charged situation, the individual with emotional skills will reflect on the situation, and adapt the response to emotion by regulating it, with the aim of adopting a behavior that he or she considers to be consistent with the situation and the emotional social rules of the organization.

Figure 3.2. Emotional skills, at the level of the interaction between emotion and cognition

Emotional skills are at the level of the interaction between emotions and cognitions (Salovey et al., 1999). They are defined as “the ability to perceive accurately, appraise, and express emotion; the ability to access and/or generate feelings when they facilitate thought; the ability to understand emotion and emotional knowledge; and the ability to regulate emotions to promote emotional and intellectual growth” (Mayer and Salovey, 1997, p. 11). According to the authors, these skills are mental, measurable and demonstrable abilities.

This concept divides emotional skills in to four. The first three are intrapersonal emotional skills: emotional perception, that is, the ability to perceive and express emotions (identifying emotions); an emotional assimilation such as emotional facilitation in thought (emotional facilitation of thought or using emotions); and emotional understanding, or the ability to understand and reason about complex emotions (understanding emotions). The last emotional skill is activated at an interpersonal level: it is the management of emotions such as the ability to regulate one’s emotions and those of others (managing emotions) (Salovey and Mayer, 1990). According to the authors, having the last skill involves having integrated the first three in advance. However, this skill is fundamental for service professions and relational professions, the so-called “risky” professions. For example, a BAC police officer, during a risky and complex arrest, will have to regulate his or her emotions (whether it is fear, surprise, anger) in the face of danger or violence, when facing the suspect, as well as managing the emotions of the latter. This activation of skills will allow him or her to both preserve his or her health at work and the quality of the intervention and the activity of the work collective.

This activation of emotional skills in work situations, or operationality of emotional regulation during arrest, deserves a representative illustration, observed during immersion. In BAC police officer crews, during a stakeout of a relatively short duration on a van stolen with violent force, the two wanted suspects appeared and opened the vehicle. Very quickly, the nearby stakeout crew burst on the scene, causing the two criminals to flee. The non-driver police officers then pursued them, and the drivers followed them in the best way possible to identify their trajectory and their positioning. The first person involved was arrested, while the second was nowhere to be found. As the district of the high-speed pursuit was residential, the criminals proceeded from garden to garden, by climbing the gates. A police officer, picking up traces of fresh footsteps, found himself alone in a garden, while searching for the second suspect. He ended up finding him crouching in a cabin, on the lookout. By evaluating the situation of isolation, the risk, and the amazing power and build of the suspect, the police officer managed the situation by activating both intrapersonal emotional skills and interpersonal skills.

In fact, from an intrapersonal point of view, not knowing if the individual was armed or not, it was a question of channeling and regulating his own emotions – of surprise and fear – not putting himself in danger nor letting the offender escape. From an interpersonal point of view, at the same time, the police officer had to call in reinforcements at once, so that his colleagues could locate him and help him to arrest the criminal and at the same time focus on the non-verbal communication of the individual in order to detect his intentions. In the end, the fellow police officers arrived when the police officer physically confronted the person involved alone, injuring himself slightly. For all the crews concerned, the arrest was regarded as “a success”, and the two individuals were arrested. During the interview, the police officer revisited the event in order to consider its emotional components:

“He was in the cabin. So you are in a state of vigilance because your senses are awake. From the moment when you have the target, when you know that he is there, when you have identified him, everything else diminishes, you focus on him, and from that moment the goal is to not let him escape, the goal is to not be injured; the goal is to arrest him. So from that moment, you anticipate everything that could possibly happen to you”; “I say that openly, in this case, I was afraid. But from the moment that you know how to control your fear, you have an advantage. (…) Experience also helps you. On this case, in this occurrence, I was afraid to get hit (…) I was at a distance from him, it is for this reason that I did not go to handcuff him alone, it is for this reason that I shouted, at him and at my colleagues so that they could join me. (…) Fear, you control it, but once you have learned how to control it, you act as a professional and my job is exactly that. The logic was this: first of all to try to ‘stabilize’ the guy, to stabilize him, between quotation marks, under control, (…) he would not kick me while taking my weapon”.

All of the interviewed police officers mention these intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional skills, which are necessary during the activity. Table 3.1 provides some quotations from the police officers interviewed, representative and illustrative of these different skills.

Table 3.1. BAC police officers’ intrapersonal and interpersonal emotional skills

| Intrapersonal emotional skills | Interpersonal emotional skills |

| Self-control: “A lot of self-control (…) you must be able to think quickly; you must have self-control: if you panic or something else happens, you cannot think about what you are going to do and then you are not doing the right things either”; “You must always be ready to react quickly but correctly, that is what is complicated. If you panic, you will not succeed”; “You must know how to control yourself”. “We cannot afford to have emotions at that moment. You will certainly have emotions, you can fear, you can feel joy, satisfaction, or an adrenaline rush, but you cannot feel anger like that all of a sudden, hatred or sadness, or empathy”. |

Controlling one’s expressions in front of the public: “You do not have the right to show that you are, in fact, weak. Because during an inspection or intervention, you must be quite strict, you must have a respondent, you must not look at your shoes when people speak to you, you must always be operational, when you should run, when you are on a fight, or on a delicate operation for example; there, you are in full emotion”. |

| Regulating anger and frustration: “There is always a notion of vigilance because anger, which you must be wary of with anger, for me, is the side… It can weaken your vigilance. Do you see? It gives you blinkers, a tunnel effect. This is called the tunnel effect among us”. “When you pass for example a day having stones thrown at you by protesters, the end of the day… Example, you take the stones until you are told to go further, and at the end of the day, you’re emotionally tired because you have been frustrated, and because you have taken it full on the head throughout the day, and you cannot do anything because it is like that, and not otherwise”. |

Controlling one’s expressions in front of colleagues and the hierarchy: “We get bored, we are disgusted during certain arrests because they are disgusting. Terror, I do not know, but fear, yes, fear and apprehension, we feel it when we go back into something or when we see suspicious people, necessarily, we have this fear. We do not show it, we must not show it, but we have it, it is obvious”. “You are guided by the law, but you see that injustice, it is here, for us, this is the most problematic thing. Because outside, they have chosen to be outlaws, the people. So this is the job. This should not be part of the business. We should be serene. So we are angry, not serene. You can show it to your colleagues but not to the hierarchy”. |

| Regulating fear: “This fear allows me to have reflexes and attitudes that make it defensive for me and it saves me from taking unnecessary risks, but I will go to the end”. | Detecting the emotions of the public: “It is someone who walks on the sidewalk, who has a way of turning around, which is not natural. We feel that the guy is stressed”, “He is not serene”; “Then, we can also be wrong, we must be able to see it. It is intuition. To have intuition, we must have disposition. We must love it. We must be active!”, “After a patrol day, normally, we must be empty. We must be tired at the end”. “A look betrays a lot to us, so I know that sometimes, when we follow someone, it is better to be an average person, i.e. when there is a person who speaks a little loud, look down as if you are afraid, so that they will not see you and everything”. |

| Detecting and regulating colleagues’ emotions: “This is especially, among us, non-verbal”; “Whether it is with the guy in front of you that you must arrest or check, or a colleague, I try all the time to analyze it”. |

The main intrapersonal emotional skill falls within the self-control category in intervention. For the police officers interviewed, the situations of first contact provoke varied emotions: “You quickly go around your petals (Plutchik, 2001)”, and these are mainly the states of anger, frustration, fear and apprehension which have to be individually regulated. An example of a daily situation, an instigator of unpleasant emotions that has been observed on multiple occasions during immersion can be proposed. Police officers, regularly and following an intervention, bring the arrested persons to the police station and must watch them in front of the detention room, starting from the drafting of the report and then when waiting for custody. Sometimes, this period is extended, if the wait for the custody process is longer. One or more BAC police officers should then stand in front of the room and monitor the accused. The contact with the arrested persons takes place directly, visually. Only the bars of the room separate them from the police officers. One or more police officers are at approximately 1–2 meters away from the persons concerned, and sometimes they are subjected to remarks, insults and attempts of all sorts, which raises, among the police officers, emotions of frustration, anger, disgust or weariness. These emotions, which the police officers describe as common and harmless, of low to medium intensity, still require self-control by them, in particular, a control of the manifestation of these emotions, their expressions, in front of the persons involved.

At an interpersonal level, police officers activate their emotional skills by detecting and using their own emotions, and those of others. In front of the public, it is a question of displaying or not displaying certain emotions, in order to properly complete their interventions and to achieve their purposes: “We are actors, we must be actors”. In return, police officers detect the emotions of “suspects”, in particular, by analyzing their non-verbal communication, their attitudes and expressions, in the objective of a “job well done”. Internally, emotional social rules apply. The police officer must control the emotions to display or not display in front of colleagues, and in front of the hierarchy. In front of colleagues, many emotions are expressed and displayed, to the extent that this emotional sharing occurs at a time appropriate for the group. The rules of emotional display between colleagues are identified in particular on the basis of moments perceived and accepted as conducive to this sharing: these are often informal post-intervention debriefings, or moments of informal exchanges and shares during breaks or commencement of duty. In general, the police officers interviewed make sure to identify and discern the emotional states of their colleagues; these states being mostly expressed through non-verbal behaviors. This vigilance towards colleagues corresponds to a mark of solidarity and mutual assistance between colleagues, and to a focus on the quality and safety of interventions. Although encouraged and promoted by all local managers, this internal consideration corresponds in particular to an autonomous collective emotional regulation (Monier, 2015).

3.2.2. Developing one’s emotional skills: accumulating and capitalizing on experiences, drawing inspiration from seniors and preparing through training

For a large majority of the police officers interviewed, developing their emotional skills requires capitalization on work experiences:

“In a (squad)? Some experience, beforehand. A certain form of maturity, I would say”, “A certain knowledge of our current missions and then also a form of equilibrium, moderation in the management of interventions, a certain form of maturity, and now, even more so now, (…) to be able to show perhaps sometimes, renunciation. Not to take reckless risks, not to be too enthusiastic”. “(Emotions), I manage them better and better, because the work forced me to find a system to manage them. It is the experiences that forced me to find solutions”; “We are exactly on Darwin! Of course! If my response is effective, I keep it. If it is not valid, in any way, you remain at the same state!” “(To manage one’s emotions), perhaps more and more, because, for example, in my first discovery (of a body), it was hard and after that, gradually, after, we… It is not classic, such as an assault, or that’s it; it is not routine but it is good, we know, we know this, already”; “Yes. I would do the same but on the contrary, at an emotional level, I… yeah, in any way, it is always sad when even… but I will be more experienced… Yeah, it is the experience”. “But on… all that is emotional, all managerial activities, it is really the past which forged all that. I have the impression that if you experience a situation – at least in this profession – if you had a weakness – it is not pejorative! You no longer have this weakness, it has been eliminated. If you had to manage this weakness at one point, you don’t come back to it, next time is different. Experience prevents this from happening again”.

All police officers interviewed noted an increase in emotional skills over time, with age and experience in the squad:

“Apprehension, I manage it better”; “This management, I developed it in my career. Emergency services, this is worse, substantial apprehension. Now, I handle it better”. “There is vigilance, already… Because you are vigilant about everything, you pay attention to everything. And then, I would say… I have learned a lot about myself… About myself, in relation to the people that I meet, in relation to the way in which you’ll manage your emotions, I learned a lot in relation to the job. You learn a lot about yourself: you know better how to manage your emotions; you know better how you are yourself; you know better yourself, this is what I think! This is what I learned most, that’s it, I think”. “I control them better. Sensitivity… In fact it is the management of sensitivity which has evolved. I think that sensitivity remains the same, after that it is the way to manage it that will differ”. “The more the years pass and the more time passes, the more I say to myself that it is natural and not necessarily shameful to feel, to express and even to show emotions. (…) maybe I assume more”.

This learning and development of emotional skills is sometimes achieved through informal mentoring, through the transmission of knowledge from the oldest to the youngest members of the squad:

“Emotional work, I did but it has been improved, I think, with experience. It has really been improved and this is also the observation of the seniors and not just mine. There is a certain transmission of knowledge”; “Me, I have learned a lot from former colleagues. They are not many, but we can talk about mentors, somewhere. They told me things clearly, and then I was inspired by them. Having models. The management of emotions, that is what they taught me, not so much for the profession itself. But the management of emotions. Particularly (a colleague) who is in the management of emotions, this may be related to their own personal culture, their personal life, who said at the level of his emotions: ‘After 2, 3 days, come back to what you were told, or what you saw, and you may be able to come to a judgment, to have an opinion. Do not let yourself be carried away by your emotions from the first moment, in the heat of the moment’. And this, sincerely, is advice that I implemented”.

Finally, preparation, anticipation and training to risky situations, representative of real work situations, will allow police officers to have a panel of behaviors to adopt in order to best adapt to the situation at moment T and preserve their health and the quality of their interventions:

“We have a whole range of weapons and protection, which makes it all happen well. But what can change the intervention, is precisely the lack of preparation. Stress or apprehension, this is preparation. This lack of preparation will open the door to many more uncertainties, and all this uncertainty, there are just as many possibilities to be injured on an intervention”.

Emotional skills, intrapersonal and interpersonal, are resources for BAC police officers. We consider them as “emotional labor tools”.

3.2.3. The emotional effects of the work of BAC police officers

Faced with psychologically demanding work objects during activity, police officers, in order to preserve their health and the quality of their interventions, deploy and work on their emotional skills at an intrapersonal and interpersonal level. Emotional labor tools and objects cause emotional effects on police officers. Pleasant emotions as work effects are primarily related to a “job well done” and relate to pride, relief:

“ … Everyone returns healthy and safe, we did a great job, we stopped something, someone, we stopped an offense, everyone is happy, colleagues are happy, it is straightforward, we are sure that it will pay off”.

However, certain unpleasant emotions, work effects, can influence professionals’ health, as well as their personal life:

“It will be more about irritability and sleep. Trouble sleeping (…) some crappy situations, or stuff that could have been messed up, we think it over, and over, and over. That, and irritability. As well. I see it in relation to my son”.

Concerning unpleasant emotions, police officers refer to the impacts of work emotions-objects, on their health, in particular, on their sleep and on irritability. “Emotional labor tools”, in this case emotional skills, although necessary during police missions, to “get all of us home, in one piece”, and to guarantee a high quality of intervention, seem to be more responsible for an emotional fatigue, a psychological fatigue:

“Well, we have moral and physical fatigue (…). Still, to have suffered certain emotions that we had to channel”.

All police officers mention the impact of “emotional labor objects” and “emotional labor tools” on their personal life, resulting in “emotional labor effects”:

“The job has demands. Even on our private life, it is huge (…). We see so many negative things, that even when we go home…, in fact we have the impression that we only see negative things (…). For me, it was necessary to express myself outside”; “I never disconnect. We will say that the level of vigilance, attention to all that, it decreases when faced with the same situation, but sometimes it is crippling”; “How you can go from such a sad feeling to a happy one! Sometimes, it is complicated to manage”.

Strategies limit these consequences on our personal life: sports, taking care of our family, having different activities alongside, decompression methods:

“I have so many things, other things [such as activities]. I am enriched in my personal life, I must disconnect, otherwise I cannot do it”; “I have many things. I box twice a week. Then, I do a lot of things!”, “I have lots of methods, and that’s why I am not, in fact, very stressed”.

These strategies of self-care, the development of decompression methods, and the balance between personal and professional life seem essential, to preserve both police officers’ health and the quality of their work, the mobilization of emotional skills requiring a certain energy to manage on a daily basis. If the police officer has no opportunity to regenerate this emotional energy, they will not, or it will be very difficult to, remobilize their emotional skills, once in activity:

“I think that we must have balance. So a balance that is achieved… perhaps through outlets: For some, it is literature, sports, anything you want… but which allow you to have a little perspective on events, situations, and therefore discernment. Even if you can be, at a given time, passionate, by what you do, you still have to see other things that allow you to take some distance” (Squad Commander); “You must have good self-confidence, good family balance. I think that it is complicated, but in the police in general. That is to say, perhaps this is the case on all same professions, we experience particular things, due to missions; and if it’s not right with you, it’s for this reason that you have so many suicides, it is never the one or the other, it is always the combination of the two. That is to say that if it’s not right with you, you go to work, but if in addition things are not right at work, about the difficulty of the work, you do not necessarily find solutions”, “I find that it is necessary to have a good family balance. I stay on it! We must have balance!”

3.3. Conclusion

“Emotional labor objects”, as well as emotional demands of the activity, are a psychosocial risk that HR function and health professionals can take into account in the framework of PSR prevention for the national police force (Monier, 2014). Emotional skills, activated in response to these requirements and work conditions, correspond to work tools which can develop and be enriched through experience, feedback, transmission of knowledge, mentoring, preparation and training. These emotional skills, intrapersonal and interpersonal, allow police officers to preserve their health during intervention, perform quality work, and also contribute to collective work, detect colleagues who face difficulties and respect the emotional social rules of the organization. However, self-control and control of emotions, although necessary in any service profession, particularly this profession with physical and psychological risks, can also emotionally and morally fatigue police officers. It therefore seems essential, beyond the importance of balance between the spheres of life, as noted by the police officers interviewed, to have internal decompression “chambers”, adding to autonomous collective emotional regulations. In order to ensure that the collective serves an evacuation of emotions and a preparation for confrontation with emotional labor objects, management must plan and supervise this collective emotional regulation (Monier, 2015). The role of a supervisor is fundamental in the evacuation and expression of emotions at work. Management must allow a “behind the scenes” (Goffman, 1959) – in the Goffmanian sense – in which individuals relax, communicate their emotions internally (Gaulejac, 2011), discuss the risks of the activity and the affiliated emotional aspects (Monier, 2017; Detchessahar, 2013).

3.4. References

DARES, DREES, Enquête SIP – Santé et Itinéraires Professionnels, available at: http://dares.travail-emploi.gouv.fr/dares-etudes-et-statistiques/enquetes-de-a-a-z/article/sante-et-itineraire-professionnel-sip (page accessed March 1, 2016), 2007.

DARES, “Conditions de travail”, Dares Analyses, vol. 49, 2014.

DE GAULEJAC V., Travail, les raisons de la colère, Le Seuil, Paris, 2011.

DETCHESSAHAR M., “Faire face aux risques psychosociaux : Quelques éléments d’un management par la discussion”, Revue Négociations, vol. 1, pp. 57–80, 2013.

EIGLIER P., LANGEARD E., Servuction. Le marketing des services, McGraw Hill, 1987.

EVERAERE C., “La compétence : Un compromis multidimensionnel fragile”, Gestion 2000, vol. 4, 2000.

FRIJDA N.H., The Emotions, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

GOFFMAN E., The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Random House, New York, 1959.

GOLLAC M., BODIER M., Mesurer les facteurs psychosociaux de risques au travail pour les maîtriser, Report, available at: www.college-risquespsychosociaux-travail.fr/site/Rapport-College-SRPST.pdf (page accessed March 2016), 2011.

HOCHSCHILD A.R., “Travail émotionnel, règles de sentiments et structure sociale”, Travailler, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 19–49, 2003.

HOCHSCHILD A.R., The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1983/2003.

JEANTET A., “L’émotion prescrite au travail”, Travailler, vol. 9, pp. 99–112, 2003.

LANCRY A., GROSJEAN V., PARMENTIER C., “Risques psychosociaux, émotions et charge de travail”, Journées d’automne du GDR Psychologie Ergonomique et Ergonomie Cognitive, Paris, November 20–21, 2008.

LAVILLE A., “Les silences de l’ergonomie vis-à-vis de la santé”, Actes des IIe Journées “Recherches et Ergonomie” de la SELF, Toulouse, available at: http://www.ergonomie-self.org/rechergo98/html/laville.html, 1998.

LAZARUS R., Emotion and Adaptation, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1991.

LAZARUS R., Stress and Emotions: A New Synthesis, Free Association Books, 1999.

LIKERT R., The Human Organization: Its Management and Value, McGraw Hill, New York, 1967.

LORIOL M., CAROLY S., “Le contrôle des émotions au travail : Le cas des infirmières hospitalières et des policiers de voie publique”, in FERNANDEZ F., LEZE S., MARCHE H. (eds), Le langage social des émotions. Études sur les rapports aux corps et à la santé, Economica, 2008.

MAYO E., The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilization, Division of Research, Harvard Graduate School of Business Administration, Boston, 1945.

MONIER H., “La gestion des émotions au travail : Le cas des policiers d’élite”, Revue Interdisciplinaire Management, Homme(s) & Entreprise, vol. 13, pp. 105–112, 2014.

MONIER H., “Les émotions au travail dans un service d’Urgences : Vers un management de la régulation émotionnelle collective ?”, Actes du XXVIème Congrès AGRH, Montpellier, 2015.

MONIER H., “Vers un “ménagement” des Ressources Humaines ? (Ré)aménager les coulisses de l’activité policière”, in YANAK Z., BRUNET S., SILVA F. (eds), Management & Sciences Sociales, Mieux-être au travail : Repenser le management et l’émergence de la personne, pp. 111–128, 2017.

MONJARDET D., Ce que fait la police. Sociologie de la force publique, La Découverte, Paris, 1996.

PLUTCHIK R., Emotions: A Psychoevolutionary Synthesis, Harper & Row, New York, 1980.

PLUTCHIK R., “The nature of emotions”, American Scientist, vol. 89, pp. 344–350, 2001.

RAFAELI A., SUTTON R., “The expression of emotion as part of the work role”, Academy of Management Review, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 23–37, 1987.

REMOUSSENARD C., ANSIAU D., “Bien-être émotionnel au travail et changement organisationnel”, Pistes : Perspectives interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la santé, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2003.

SALOVEY P., MAYER J.D., “Emotional intelligence”, Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, vol. 9, pp. 185–211, 1990.

SALOVEY P., MAYER J.D., “What is emotional intelligence?”, in SALOVEY P., SLUYTER J.D. (eds), Emotional Development and Emotional Intelligence, Basic Books, New York, 1997.

SALOVEY P., MAYER J.D., CARUSO D., “Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence”, Intelligence, vol. 27, pp. 267–298, 1999.

SCHERER K., “Psychological models of emotion”, in BOROD J.C. (ed.), The Neuropsychology of Emotion, Oxford University Press, 2000.

SCHERER K., “Appraisal considered as a process of multilevel sequential checking”, in SCHERER K., SCHORR A., JOHNSTONE T. (eds), Appraisal Processes in Emotion: Theory, Methods, Research, Oxford University Press, New York, 2001.

SOARES A., “Tears at work: Gender, interaction, and emotional labour in the brazilian service sector”, 95th Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association, Washington, 2000.

VAN HOOREBEKE D., “La contagion émotionnelle : Problème ou ressource pour les relations interpersonnelles dans l’organisation ?”, Humanisme et Entreprises, vol. 279, pp. 53–70, 2006.

WEISS H.M., CROPANZANO R., “Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work”, Research in Organizational Behavior, vol. 18, pp. 1–74, 1996.

WIKIPEDIA, Plutchik’s wheel of emotions, available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Plutchik#/media/File:Plutchik-wheel.svg, 2018.

ZARIFIAN P., Objectif compétence, pour une nouvelle logique, Liaisons, Paris, 1999.

Chapter written by Hélène MONIER.