Chapter Two

Guiding Principles for Anytime Everywhere

There are many ways to share your message with supporters, call a community to action, and ask for feedback or support that will ultimately help you spur social change. Organizational communications are increasingly personal and direct, thanks to social media platforms and the prevalence of public access points. Yet despite the increasing number of methods for reaching out to and communicating with your constituents, certain guiding principles remain the same. Like houses, there are many different architectural styles, but certain elements are critical to structure—no matter what, the walls must support the ceiling and the doors must align with their frames. Whether you have a modern brownstone, a farmhouse, or a large Colonial style home, there’s a foundation under the floor, nails and screws joining pieces of wood, and insulation in the walls and ceiling.

The same is true for campaigns, appeals, and for building a movement. During our work with organizations of all sizes and missions, we’ve identified five principles as integral to a structurally sound campaign or movement. These five principles are the “make it or break it” checkpoints, regardless of whether you are a community group or enterprise-level organization, creating a political or advocacy campaign, or launching into short-term or year-round fundraising efforts.

Keep these principles in mind as you develop your strategies and communications. In the preplanning stage, let these principles shape your decisions about audience, voice, and which platforms to use—they will help you and your colleagues navigate many conversations and add focus to your strategic planning.

You should also use these principles during the active phase of events, campaigns, and projects. As anyone who has ever sent out an email to more than one person or who has organized an event knows, your work only increases after you hit the send button. As the reach and traction of your message grows, you need to evaluate and evolve your work continually to ensure that you are still on target. You need to make changes to reflect any shifts in your community, goals, and accomplishments. These principles serve as reference points for that reevaluation of your work during the active phase, and also afterward.

Regardless of the channels you use or the goals you set, these five principles should influence the way you operate and contribute to the potential success of your endeavors. Let’s look at each of the principles in detail.

PRINCIPLE 1. IDENTIFY YOUR COMMUNITY FROM THE CROWD

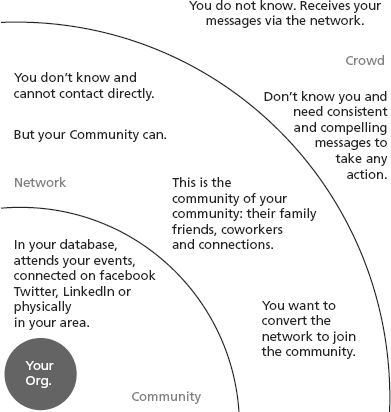

The words community, network, and crowd are often used interchangeably. They are not, however, interchangeable. These three words indicate very different segments of people, and you should use them to denote not just whom you engage and communicate with, but also how and why. You can see the three groups in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1 Community, Network, and Crowd Defined

Your Community

The ring closest to your organization represents your community. This is made up of people you can contact directly. Their email addresses, phone numbers, or mailing addresses are in your database. They receive your email messages and appeals. Maybe they attend your offline events. There is nothing preventing you from communicating with them directly.

Your community members have opted in to engaging with you. That opt-in comes in various forms—for example, maybe they signed up on your website to receive email updates from you, “liked” your Facebook Page, or subscribed to your YouTube channel. If you buy a list (that is, you acquire new names and contact details from similar organizations or campaigns), those new “names” aren’t part of your community until they confirm their participation or connection.

Your Network

The next ring represents the people who are just one step farther out from your organization: your network. You can make some educated guesses about the people in this category—they tend to be the family, friends, colleagues, and coworkers of the people in your community. Your messages, information, and updates reach your network through your community. Your community members are the messengers, not you. The community may share your links or posts via Facebook; they may let their friends and family know that they support you or donate to your campaigns. Maybe your organization creates and posts beautiful, compelling photographs that community members enjoy sharing across the web, or printing and posting in their office or home. Whatever the content or platform, your messages move through the community to the network. And when members in the network find a message interesting, exciting, or compelling enough to sign up for your email list, like it on Facebook, retweet it on Twitter, or subscribe to your organization’s blog, they convert themselves from a member of the network to a member of your community.

The Crowd

The last ring, farthest out from your organization, represents the crowd. In the most general and literal sense, the crowd is everyone else—the whole world. However, in planning and evaluation, the crowd comprises all the people we hope to reach who aren’t connected to us through the network. The way we communicate when we speak to the crowd is very different from the way we speak to the community—we can’t be as personal and are guessing at how to make our message relevant. The crowd is the biggest segment, but that doesn’t mean it is the most influential or most important of our multichannel strategies. Information about online networks and the web shows that you should focus on how to best tap the power of your community and network to spread your message, and not overestimate the chance of the crowd stumbling across your message and distributing it for you.

You’ll notice that none of the words in Figure 2.1 are “audience” or “service area”; that’s because all three sections (the community, network, and crowd) already may be part of your organization’s audience or service area.

For example, if your organization were the Northwest Indiana Times, a regional newspaper, you would not actually engage with every member of your service area, since that could reasonably translate to every resident in northwest Indiana and even the southeast suburbs of Chicago—you don’t know who they all are or what they all do. Your community is thus composed of the people who subscribe or buy papers, connect with your reporters or stories by following them online and commenting on posts to your website, and attend your offline events. Their friends, colleagues, coworkers, and family are the network—the people you reach through your community. The network knows about you but isn’t yet directly connected. Maybe a friend of someone in your community told them about a story or a featured series they read recently, or they have family members who attend an annual event sponsored by the paper. The crowd is everyone else who lives and works in the neighborhoods in northwest Indiana; yes, they are part of your service area or audience, but you haven’t reached them yet.

Ultimately, you should have a plan for each of these segments of your audience. Communicating with the crowd, network, and the community are very different but can be really valuable to the success of your campaign or call to action. Setting goals and defining your message for each group at the start of your process will help you effectively engage with each group.

The core elements in building relationships with the crowd, network, and community are time, action, and people. You can use these three elements to help you identify the various options for any given engagement.

Time

Is this a one-time or sustained engagement? Is it just an event, and do you have the capacity to maintain or support a community around it once the event is over? Recognize the limits or options within your organization—what capacity do you have to maintain the action you’re considering?

Action

The action you want people to take—remember, even if your message or campaign doesn’t have a “call your Congress person” or “sign this petition” action, you are still asking them to do something. Actions can be passive or active. An active call is more appealing to your community and less appealing to the crowd, because the community members already know you, trust you, and have opted in to support your work. This kind of action might include sharing a personal story or experience, recruiting a friend to join the campaign, or signing up as a volunteer.

Similarly, a passive action isn’t very interesting to your supporters, considering that they are already taking passive action by following you on Twitter or signing up for your email list or campaigns. But a passive action can be attractive to the crowd if it is simple and provides value directly. For example, posting an infographic showing important facts about a piece of proposed legislation provides valuable information to someone whether or not they know about your organization; and it is an easy request to ask people to share it with their friends. These actions are usually things that the community may do as a way to show they are listening and connected but can be of more interest to the crowd because of a focus on a larger topic, news story, or even an interesting issue.

People

Who do you need to reach? Is it the crowd, community, or a hybrid? It is important to have a plan for each segment and an understanding of what your message is for each group. You may run a campaign or promote a targeted call to action to your community that asks a lot of their time, energy, or support. During that same campaign, a message for the crowd would focus on sharing information or learning more about the focus of the campaign—things that require less commitment.

Table 2.1 is a quick reference guide for designing for each group.

Table 2.1 Engagement Overview for the Community and Crowd

| Designing for the Community | Designing for the Crowd |

| Customizable—let the community own your message and cause by personalizing their involvement or output. | Shareable—messages, content, and actions that are shareable can be picked up and pushed around the network and crowd easily. |

| Consistent/clear/compelling goal—your supporters have joined you because they care about your cause (sometimes, even if it doesn’t seem like anyone could care any more about it than your organization, they do!) so provide clear and inspiring goals to meet together. | Consistent messaging—to ensure that this layer of people who do not know you are able to understand what you do and who you are, your messages need to be consistent. |

| Aggregate and promote—be sure you are pulling together all of the contributions from the community and promoting people in real time. | Compelling story—research continues to show that compelling stories are one of the most important triggers to donations and actions. |

Opportunities for your organization to build trust, catalyze action, and affect change exist at all levels of the human landscape. To be successful, however, it’s crucial to recognize which group to target, how to communicate, and what to say. Some of the best metrics of success are the size and engagement level of the community ring. Is it growing? Are people taking on more responsibility and leadership? Are you increasing the number of people who are volunteering or stepping up as champions of your cause or superfans? It’s important to achieve a balance between your goals for crowd-to-community conversion and your goals for leadership development within the community.

PRINCIPLE 2. FOCUS ON SHARED GOALS

Let’s be realistic: your community—even your most die-hard fans—isn’t interested in everything your organization does. (Okay, we all have that one volunteer that is, but that’s another story for another book.) It’s crucial to recognize that not everything your organization wants to do or achieve matches up exactly with all that your community wants to do, and vice versa. And that’s okay!

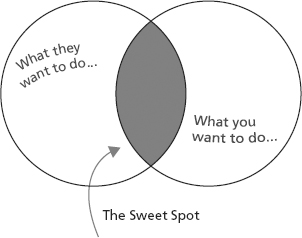

Maybe your organization provides important local services that your community appreciates but doesn’t want to be responsible for managing. Or maybe the community wants to create a new park or a new local government department, but your organization isn’t interested because the project doesn’t advance your mission. The good news is that there are programs, services, projects, and groups that both the community and your organization want to help fund, improve, and support. Figure 2.2 describes that sweet spot, where you can focus your calls to action and community engagement.

Figure 2.2 Focus on Shared Goals

First, identify what your community wants to do. What are the issues that bring the community together? An event? An action? A movement? What are hot topics for them in the news, in community meetings, and during elections? What are the values and priorities not only of community leaders, but also of general members?

Next, identify what you want to do. What are your organizational goals? What outcomes have you identified in your strategic plan? What does success look like, and how will you know you’re meeting your mission? What are you doing to gauge your impact?

The sweet spot in this case is where your organization’s and your community’s must-haves and wish lists overlap. That’s the place where you can invest your time and your energy, knowing that you are all rooting for the same end. This means that instead of spending all your time, energy, and messaging recruiting supporters, you can focus on getting people to take action. Knowing the topics that both you and your community care about can transform individual campaigns, communication, and events into successful community-building work.

You may have a whole list of specific topics, proposals, and projects that bring you and the community together. Or you may have just one point of overlap. This visualization of goals is not intended to imply that the community never wants to hear about the other work you do. It’s great to include updates about services and programs that don’t directly overlap in your communications or appeals, but focusing on the items in that sweet spot ensures that you have an engaged community working alongside you—online or offline, locally or globally.

Community Mapping

Principle #1 focused on identifying your community from the crowd. There are also subgroups within your community. Every email campaign you build isn’t going to interest every person on your list. Recognizing the groups within your community and segmenting them by their goals (and your own) helps ensure that messages are well received and that people take action. It also positions you well for successful engagement across your community. We call the process of segmenting your community by type and goal “community mapping.” First, identify the groups, and then identify your goals.

Identify the Groups

To start mapping your community, you need to identify the groups within it. There are big buckets of people such as volunteers, donors, and advocacy supporters. And within those, there are even more specific and narrowly defined groups—take volunteers. There are year-round volunteers, event volunteers, volunteer trainers, and youth/school volunteers, to name a few.

In our experience, the more diverse group you can get together in your organization to discuss and brainstorm the groups in your community, and work through this planning together, the more complete a picture you can draw of your community. When people who work in services, programs, grant writing, and fundraising, for example, get together to share their view of the groups that constitute the community, you can have rich discussions about the way different parts of your organization view and interact with the community.

Identify the Goals

The next step is identifying the goals associated with each segment. There are actually two sets of goals: The first are the goals of that specific segment—what do they want from you, why do they want to come to you, and what do they get out of it? The second are the goals your organization has for that group—what are you hoping they will do, how will they contribute, and what are you asking of them? For example, your event volunteers may be interested in free access to galas, speakers, or concerts you host, as well as including volunteer experience in a field they are passionate about on their résumé. Your organization’s goals for that group may include the value of additional event support staff, as well as increased engagement of community champions that support your cause.

Again, this conversation can be really eye opening as a part of building the community map; it can also encourage dialogue within your organization and provide clarity around the organizational goals and how they play out in community engagement.

To use ourselves as an example, do you remember how you used to answer the question, “What do you want to be when you grow up?” When Amy was in elementary school, she said professional athlete! Allyson said an astronaut. Today we enjoy watching these professionals from a distance, but we’ve pursued wildly different paths. People change. Consider your community map, which identifies the segments and the associated goals, a living document and resource for your organization. When people change, the map should too! If a new group of supporters takes shape, add it to the list. Or if a group’s interests change or evolve, reflect that in the document. As your goals for various groups change with your work, make sure you update the map.

There’s one more step to the community mapping process, but we will talk about that in the next section.

PRINCIPLE 3. CHOOSE TOOLS FOR DISCOVERY AND DISTRIBUTION

You’re online, reading a news site that has just published a list of the “Top Cities to Visit this Year.” Your city is number one! You’re excited and proud, and want to share the positive review with your friends and family; so what do you do? The news site has already included social sharing options within the article so you can easily post it to Facebook, Twitter, Google+, and many other platforms. You choose Facebook, and just ten minutes later, you see that three friends in other cities have commented on it and two friends have posted it to their Wall.

That’s often how sharing happens. Good content appeals to our interests and offers easy ways for us to distribute it. We share it as individuals (or organizations), and then our friends (the network) pick it up. Understanding the best tools and platforms for sharing content and calls to action are crucial to the level of engagement and reach of your message. Said another way, your message will only get picked up or spread if you think strategically about access and distribution.

Although this book is intended to help you focus at the strategic level, we will still talk about tools and tactics throughout the various examples and case studies. What do we mean when we talk about access at the strategic level? What does distribution really mean with social and mobile technologies?

Align Tools with Groups of People

Just as different restaurants or neighborhoods see different people, the user base of each tool, application, and platform is slightly (sometimes dramatically) different. Part of this comes from the functionality that each offers, and the types of users who are interested in or attracted to those options. People often adopt or ignore tools based on cultural and social norms. Certain elements or requirements can also influence the types and numbers of users. Is the application free or does it come with a cost? Is it only available in English or are there various languages supported? Does it limit the amount you can upload or create or does it even limit how often you can use the tool? You can explore various divergences in user groups and data in the infographics provided in Chapter One of this book.

This is the last step in the community mapping process. Now that you have identified the groups and their corresponding goals, you need to couple those groups with the spaces, platforms, and applications where group members congregate and where you can communicate with them. Even though many of these will be online channels, don’t forget about the offline spaces. Identifying the mechanisms you can use to communicate with each group may help you target your efforts, but in many cases, it illuminates areas where only one or a couple of groups use a certain platform while others use something else entirely—this fine-tuning helps you figure out which topics to promote when given the segments using those platforms, or the platforms in which there may be many different segments coming together.

Identifying Preferred Tools

How do you know which tools these groups use, especially if you aren’t on those platforms yet? Remember that you have access to a great source of information: your community. Ask them! You can ask in myriad ways, via an online survey or a Facebook poll, for example. Include questions about preferred tools and platforms in other surveys or feedback mechanisms you have in place. Ask at offline events, and solicit information and suggestions in your communication subscription options or other sign-up forms on your website. You can also use Google Analytics and other tools to learn what platforms your community is using. Which social networks refer the most people? Are those networks where you already have a presence? It may be that your community members are sharing your blog posts or fundraising campaigns with their friends and family online via platforms that you don’t even use!

Once you’ve investigated the tools your community and network prefer, dip your toes in and give them a try. You can’t fully understand the potential of a tool or evaluate whether it is the best option for your organization without using it yourself. This does not mean that you need to set up a full organizational profile on every new social network and mobile application. You can create an account and try out functionality as an individual or as a team first. When experimenting with a new platform, set a few goals for yourself that are similar to the kind of engagement or functionality you would put in place if you were deploying the tool for the organization. Use those goals as guides to help evaluate whether it is worthwhile to spend additional time and energy on the new platform or to set up an official organizational presence.

Your messages and calls to action will fail to reach your community if you aren’t sharing via the tools the community uses; similarly, the community will not share your messages on your behalf if doing so is difficult. When you evaluate tools to use as an organization or as part of a campaign, be sure to include a review of the content sharing options—for example, are there clear options to post to social networks built in? You also will want to spend some time on new platforms, observing how the tool is used by the community, looking especially at how sharing happens. Keep in mind that you shouldn’t determine sharing practices based solely on which platforms users prefer—the type of content is also important. Images and videos are extremely popular media for creating and sharing from both the web and mobile devices.

Take Tumblr, a popular blogging platform, as an example: Users re-blog (post another user’s content to their own page) the average Tumblr post 9 times (resulting in only about 10% original content throughout the platform as a whole).11 It is critical that content you create for your community to share includes appropriate links or information for readers to find your organization.

A great example is the image-centric “Rise Above Plastics” campaign from the Surfrider Foundation.12 The images are compelling and striking, but simple and direct messaging make them ripe for sharing and posting on social media. Just a couple days after launching, thousands of people had shared the images. Smart design ensures that the images contain all the information that is needed, including the call to action, the organization’s name, and the campaign URL. This way, it does not matter whether it’s community members, animal lovers, or even photographers who share the images without fully comprehending the campaign. When people share the image, they share a whole package, which helps the campaign reach many more people than it would if it relied on individual users to include the Surfrider Foundation information and credits every time.

After identifying the community, focusing on the shared goals, and matching groups to the tools they use, many organizations ask us next: What do we talk about? That’s the next principle! (Also, in the Advocacy chapter, we discuss how to identify where your community hangs out online and provide examples of platforms popular with specific communities.)

PRINCIPLE 4. HIGHLIGHT PERSONAL STORIES

When presented with somber news, such as a famine in a foreign country and the magnitude of suffering that goes along with it, many people feel overwhelmed by the need. In contrast, when presented with the story of just one person impacted by the famine, people often feel like even a small donation or action really can make a difference.

Why is this the case? According to the psychology of giving, which we explore more in Chapter Four, “Fundraising Anytime, Everywhere,” people are motivated to donate money when they can personally and emotionally identify with a single person in need. And as much as we desire a peaceful and just world, we also want to know that our giving has a real, positive effect.

Our community wants to help others, and the more directly we can achieve that, the better. Email, social and mobile technologies, and our own websites give us the opportunity to use storytelling to craft these clear appeals. Technology allows members of our community to share stories in various ways, provides organizations diverse platforms for storytelling, and helps us reach more people and raise more money through the way it distributes those stories.

Individuals

Social publishing tools and the web make it easy for people to share their stories across a range of media. Whether it’s photographs, videos, or text—or a mashup of media—your community members can share on social networks, local news sites, blogging and micro-blogging platforms, and even media-specific networks such as YouTube (video), Audioboo (audio), and Flickr (photographs).

The web is full of people posting their stories, updates about what they are doing, and even news that resonates with them. How do you get your community to share stories about your work or about the way your organization is impacting their lives? First, you have to ask! Most likely, you do not have many community members who, without prompting, will take the time to tell you how much they appreciated or learned from or benefited from the work you do. If you ask your community for their stories, you’ll find people open to sharing.

Many organizations try to incorporate personal stories from their community—either from people who benefit from services and programs or those that support their work—in advocacy campaigns, fundraising appeals, and general operations updates. If you have the capacity to directly recruit and craft these stories, you probably have a standard structure for collecting information—maybe a set of questions you use for every interview you conduct with program or service participants or a format you like to use in an annual report.

That same structure can help you tap into the community to have individuals tell their story related to your services, program, or mission. Share a prompt for people to respond in a Mad Libs–like style: “Complete the sentence, ‘I’m walking for Diabetes because ___, and I hope you will support me by ___.’” Post an example story from your staff or volunteers and ask for others to share their version, whether it is a written story, a photo, a video, or a combination. Ask an open-ended question using the medium or platform you want people to respond with; for example, pose the question in a quick video and ask viewers to create a short video response with their answer.

Regardless of the kind of content or where people post it, providing structure for what to create and how to share it gives the community a starting place to share their story for your organization. Similarly, be sure you are also the first to complete the prompt, or create a video, or upload a photo in the way you are asking your community to do. This is a great way to seed the space with content and provide an example that meets your criteria—your supporters can see what to do to participate. You don’t want the same staff person always in the spotlight? Rotate in other staff (ask ahead of time) or tap your biggest supporters with a request and a sneak peak.

Organizations

It’s exciting and inspiring to see your community members share their stories as part of your campaign or in support of your message, but as an organization, you have an equally important and inspiring role to play in storytelling. Storytelling is a two-way process. If the individuals that respond to your prompt or call to action have nowhere to share or no one to share with, the motivation for sharing and the potential number of participants are greatly diminished.

The web is a vast repository of pages, pictures, and information—stories are everywhere. When your community starts contributing their own stories, your organization must reciprocate by aggregating and showcasing the stories. By pulling together content, through tags (the use of keywords to identify content) on various platforms or by using a dedicated group on a specific application such as Flickr, you have the potential to transform a set of disparate stories into a pool of supporting voices for your work. Tools such as Tumblr, Flickr, YouTube, and Twitter are often utilized in campaigns as popular places for posting as well as sharing content. Similarly, tools such as Pinterest, Scoop.it, and Storify help organizations and community groups curate content in real time for aggregation and sharing.

Regardless of what content or platforms your community uses, you have many options for collecting their contributions, both within a platform and back on your website. Pulling together content on your organization’s website or a campaign-specific microsite is important, as it places the stories and comments from your supporters where visitors can find out more about your work or get involved, thus showing the value you place on their voices. It also validates the contributions of individuals by giving them space in your organization’s online property.

When you aggregate the stories, you also have an opportunity to spotlight contributors and community members. You might highlight a specific story in an email appeal, feature someone’s story on the top of your blog or in the banner of your website, or even spotlight stories on your social media channels. New visitors are drawn to personal stories, while other community members are inspired to contribute and share the spotlight. This is a key leadership development component, and in campaigns or appeals like this, it serves as a mechanism for encouraging participation and identifying superactivists, donors, and fans.

Just as individuals in the community are sharing their personal stories, you can tell the bigger story by bringing together single voices, using data to create a story, and creating a space where the community comes together with your message. Data can tell stories too. As you aggregate contributions from your community, take advantage of any additional data you’re collecting to help tell a larger story, like the locations where the most requests for help are generated or the distribution of ages of contributors. Whether you use a map (like Google Maps) to plot the locations of contributors or their stories and photos, or tools to count or visualize the numbers, words, or funds contributed, as an organization leading this storytelling effort you can pull the voices and the data together to support your mission.

If you’re collecting or aggregating content and conversations created by your community on your own website or a campaign microsite, you are providing context and supplemental information within the actual space where the content is showcased. If you use tools for curation (an industry term meaning aggregation coupled with narrative or notation) that house the content on a third party platform (such as Pinterest, Scoop.it, or Storify), it’s important that you add contextual information, links, and other general descriptions to the accounts and individual content pieces. Curation allows your organization to shape the larger story and add in a frame or lens for the community to see stories linked together or as evidence of a bigger picture. For example, as news is breaking about a piece of legislation important to your cause, you could use a tool like Storify to pull together tweets, news links, and blog posts along with your notations about what the decision and impact mean for your community.

Personal storytelling is an important building block of the Internet—it manifests in blogs, social networks, and niche topic forums. Tap into the natural inclination for humans to share by providing a clear prompt that your community can respond to and the network and crowd can share.

PRINCIPLE 5. BUILD A MOVEMENT

Just as the terms community and network are often, and incorrectly, used interchangeably, the term movement is often misused or vaguely defined. So what is a movement? Here are some parameters. Movements are larger than partnerships and coalitions. They are deeper than engagement, and longer than campaigns. A movement is inherently counter to branding and requires the participation of more than just a few inspired individuals.

As such, a movement is built on collaboration and encourages co-creation between individuals and organizations. It remains focused, even in the midst of specific events or campaigns, on the larger goal of lasting, real impact. To that end, movements that have unifying goals—goals that rally both individuals and entire communities—replace brands operating in a silo.

Branding

More than ten years ago, long before the namesake organization formed, “350ppm” (indicating 350 parts per million), used as a tag or category on blogs or a keyword on files and images, was a rallying point on the web. It helped bloggers find each other’s content, facilitated photo and documentation sharing among environmentalists and nature lovers, and helped individuals find and share news about the impacts of or legislative actions related to climate change. Over time, as interest and the community grew, an organization took shape and based its name on this “call sign.” It became 350.org. The community’s process remains the same. People of all backgrounds, in all locations, and in all occupations use “350” or #350 on social networks, in signs, and in photographs, during global action days and every day in between, to indicate their affiliation with the climate change movement. As exemplified by 350.org, there are tremendous opportunities for starting and growing movements by focusing on a singular change or action.

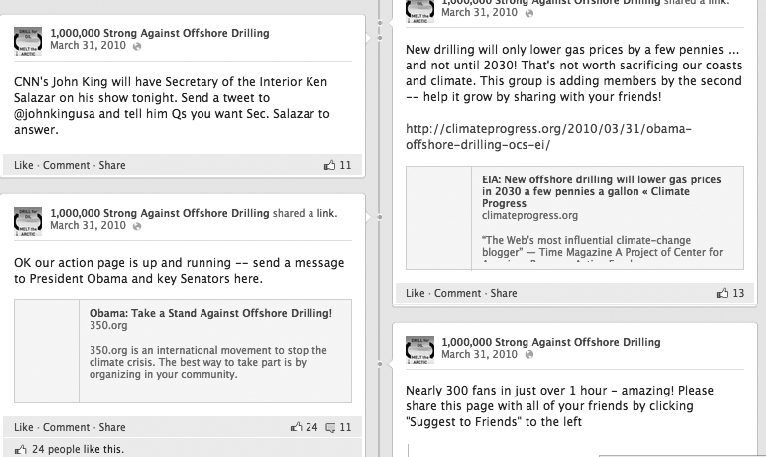

Figure 2.3 is a Facebook Page where many organizations across the environmental, climate, and animal welfare sectors came together to share news, updates, action alerts, and much more after the BP Oil Spill. You can see it’s focused on action. There’s a petition built into the page and the page doesn’t have an organization’s name—it doesn’t even have anything about BP in the name.

Figure 2.3 1 Million Strong Against Offshore Drilling Facebook Page

In recent years, some very large organizations have been in the public spotlight as they try to manage and control their branding via extensive lawsuits and legal battles. For example, Susan G. Komen for the Cure’s efforts to maintain the exclusive use of pink ribbons, and even the color pink and the phrase “for the cure” by suing other nonprofits has landed them in the online and television media.13

Nonprofits, like all organizations, have the right to safeguard their trademarks, but many view the Komen example as just one illustration of an organization fighting to “own” a cause. Doing so diminishes your opportunities for true movement building and catalyzing impact. Why? Because if your organization seeks to own the idea of, say, a future without cancer, any organization working on that issue is off the list of potential collaborators and champions. Working in an anytime, everywhere world with our supporters and all those trying to create a better world will require that we reevaluate how we market and safeguard our brand.

Co-Creation

Actually creating social change anytime, everywhere relies on your organization’s ability to let go of some of the more traditional ideas about social action, campaigning, and organizing—mainly, the idea that an organization is in control and orchestrating the community’s every move. Certainly, there are some elements of an organization’s work that the community probably isn’t interested in (usually the boring stuff!), but communities around the world are getting used to playing a role, along with organizations and service providers, in creating change.

As we said earlier in this chapter, when evaluating your goals and the goals of your community, it’s critical to identify the role of your organization and the roles of your community leaders, partners, and groups. Many organizations focus on including the community in their work only after they are ready to launch the campaign, announce the new program, or start registering new users. In an anytime, everywhere world, organizations that wait to bring the community in until this unveiling point are missing out on the potential for collaboration and support, as well as direct feedback and guidance that can make for a better and more valuable product, service, program, or platform.

We aren’t suggesting that you do your planning work in huge public forums, with decisions by consensus. There are plenty of opportunities to invite interested community members to form an advisory committee, beta test and provide feedback, or post regular updates about new programs or plans in the works that the community can respond to. Working in tandem with your community—listening to needs, surfacing ideas, and sharing responsibility to move things forward—is really about empowering your community for co-creation, not just adoption.

Co-Creation Cycle

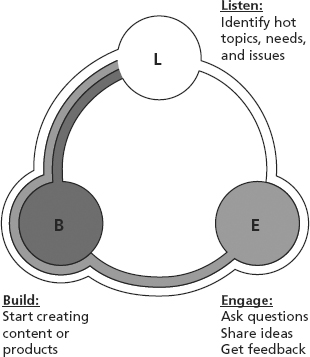

Co-creation is one of those terms that, for many of us, gets our heads spinning. Many people have defined it in different ways, contingent on the context and product they were working with. For social impact in an anytime, everywhere world, co-creation is a process or cycle that helps you be responsive, iterative, and inclusive in the way you work with your community.

As you can see in Figure 2.4, there are three distinct components of the co-creation cycle: listening, engaging, and building. The first step is listening to the community—asking questions and gathering feedback. Next, you reach engagement. You don’t stop listening, but now you are also sharing back what you hear, asking for clarification and really fleshing out ideas with the community. If you try to jump directly to this stage, without dedicating time to listening first, you can get frustrated with incomplete or ungrounded conversations. Community members can also get frustrated talking about topics or having conversations about issues that may not match their goals or interests.

Figure 2.4 Co-Creation Cycle

The third segment of the cycle is building. Again, your previous elements do not cease when you reach this point; you want to continue to listen and engage with your community, but now you are building out the ideas directly—whether it’s a website, a piece of content, or a whole campaign. This is where the cycle really becomes a continuous process: once you’ve done some of the building work, you should pause to focus just on listening to feedback and responses, then build up to engagement again, and then another round of building. This second or third (or 50th) turn around the cycle may have a shorter duration for each component, but it is important that the process includes a pause to gather feedback and engage your community so that you don’t leave them behind as you build and launch something new.

The three elements of the co-creation cycle also lend themselves to different groups in your community and different numbers of participants. Many community members may share their feedback or ideas, but for most organizations there are far fewer community members with the interest or capacity to participate in the building phase. That’s certainly okay, though, and very natural. Providing opportunities to engage at all levels helps increase the total number of community members involved and the feeling that they have influenced the end results.

Slacktivism or Micro-Action

Some critics of social media engagement call actions that don’t take much effort “slacktivism” or “clicktivism,” the terms used by many to mean a “slacker action,” especially things akin to a “like” on Facebook or a “retweet” on Twitter. We think the conversation needs to start by talking about information. Regardless of the era (this isn’t a new phenomena), the emphasis and effort spent on spreading information and raising awareness has always resulted in people doing what organizations ask, even if it’s considered slacktivism. Previously, learning, spreading information, and raising awareness were very passive actions. With the rise of social media, we can further confuse the information stage of campaigning or change efforts with an active action.

Social media is a tool, not a tactic or a strategy. Whether you are urging supporters to make change or chronicling the revolution in your state, it is still a tool. But because social media allows people to engage and share personal information, it’s very easy and common for organizations to be satisfied with asking for and measuring the information stage.

Let’s take a step back for just a second and look at how our modern slacktivism came into this information-equals-activism dynamic. Just as social media was really taking off, people and organizations were caught up in new ways to gain brand recognition. Marketing strategies focused on the idea that nonprofits should recognize that they could be just like companies in messaging, recognition, and branding. Visibility and information sharing were the keys.

Here’s a great example. How many of us had a plastic bracelet from one organization or another, or maybe we still do? How many of us worked for an organization that created bracelets for general marketing or a specific campaign? We did! And it was an organization with a staff of three and a board of twelve. Why’d we do it? To get into people’s lives, to start increasing touch points toward fundraising asks, to be part of how people associated themselves. Most important, it was to build awareness of our work.

Now instead of rubber bracelets, we have Facebook Fan pages. There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with a Fan page. But as organizations or campaigners, there is something wrong if we praise likes and count followers instead of understanding that our fans are primed for real action and that we should build opportunities for them to engage in something meaningful.

Metrics

Let’s look at your organizational metrics for a minute. What do you measure every day, week, month, year? What do you point to when funders, donors, board members, and the community ask if you are making a difference? How do you evaluate your programs and services? Those metrics and accompanying goals are the best resources for identifying the focus of content and the calls to action for your campaigns and even daily messages across channels.

When you ask your Facebook fans to “like” a post, you’re telling those fans that to support the organization, all they have to do is click “like.” It’s no wonder, then, that clicktivism and slacktivism are slapped on top of much of the engagement organizations have online. Liking a page, liking a post, and all the rest are not the actions and real impact you’re looking for, ultimately, but those actions are important! Why? Because, through them, people are telling you that they want to hear about what you’re doing and that they will do what you ask to support the cause. The opportunity is for you to hear that response and give them more than a post to like—give them something with more forward motion for your mission or campaign, like signing a petition, watching an informative video, making a pledge, or recruiting their friends.

What we are measuring obviously impacts what we focus on. When the only things we are tracking are the number of fans on a Facebook Page, or the number of email addresses in our database, we set ourselves up to feel satisfied with slacktivism alone—that those small signs of interest from the community are all that we need. Instead, look at your goals and build metrics that actually track your progress. Yes, the number of fans on Facebook still counts, but it is just one data point to help explore the full context of your engagement. For example, you could also track the number of community-generated posts to the Facebook Page wall versus staff posts, the number of comments from the community versus staff, the kinds of content that generate the most response, and the level of engagement (whether it’s just likes, comments, or outside action).

Likes, retweets, and other simple actions are still valuable and a great way to support visibility and information sharing, just like the bracelets. When a supporter likes your post on Facebook, that content and action show up in the news feeds of their friends, helping move your messages out to the network. They are also valuable in that they keep your supporters feeling connected to your work and up-to-date on the latest news or information related to your cause or issue. We aren’t suggesting that you discount these simple actions entirely, but ensure that they are tracked with the right context and in tandem with other actions tied to your goals.

If we consider slacktivism a micro-action, how do we move “likes” into real action?

We need to recognize the critical role we play as organizations. For all the negative talk about slacktivism, people are failing to recognize that it constitutes a huge community response. People are taking the actions we are asking them to take—we are the ones giving them slacker-actions! Instead of crafting a compelling message and asking people to like it, we should see all of our fans as community members who have raised their hand, saying, “Please give me something worthwhile to do for this cause!” and give them opportunities to start making real change—whether through advocacy, fundraising, or community-based calls to action, as we discuss in the following chapters. Recognize the role of those more passive engagements (the likes and the retweets) as small touch points, keeping people connected between the other calls to action.

We are so caught up in social and mobile technologies as a concept, a topic, causes in themselves, that we forget to move people up the engagement ladder. We forget to connect to people, period.

Impact

Your organization probably has an important mission and valuable programs or services. Your campaigns may have big goals and your messages may be filled with compelling stories that your community reads and shares. But your organization is just one piece in a network of individuals, organizations, government agencies, or businesses that are working toward or supporting some of the same ends. Even if you partner with other organizations on a project, that partnership is just the beginning of real movement building.

When those partnerships lead to sharing data so that more tracking, planning, and communicating supports real action, then you are one step closer to building a movement. Two organizations focused on climate change policy, 350.org and 1Sky, took this approach in 2010, sharing data and combining the strength of their communities for campaigns and petitions. In early 2011, they announced that they would fully merge to better tackle the issues around global climate change. Figure 2.5 is a screen shot from the announcement.

Figure 2.5 350.org and 1Sky Website Announcement

Shortly after the 350.org-1Sky announcement, David Foster, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance (BGA), showed that he shared a similar vision for his organization and the sustainable energy organization Apollo Alliance:

I believe that the decision to combine the BlueGreen Alliance and the Apollo Alliance is one of many important steps that all of us need to take to forge a stronger movement to demand the transition to a clean energy economy. But building a movement that can lead to a new direction in Washington, D.C. will not come easily, nor can it rely on sticking to old orthodoxies. We simply must be willing to build new partnerships and take risks on new organizational structures. The BGA-Apollo merge is done in that spirit.

We don’t share these examples of mergers to say that there are too many nonprofit organizations or that we believe more organizations should merge. Instead, they are examples of what it looks like when we truly double down on our focus to create change. And just as David Foster shared in the merger announcement, building a movement requires partnerships and risks.

Part of the structure that goes into building movements is the way we organize all those participating. Another component is the way we position organizations and communities to come together. Organizations may have the research or data, and the capacity and staff, to identify problems and opportunities and to build messages, calls to action, and campaigns. But the organization can’t make the change alone. The community, partners, and government are all necessary to really make a change. Organizations need to let the community drive. That doesn’t mean organizations sit back, relinquish all responsibility and control, and wait for the community to take action—quite the opposite! The organizations get to do everything but drive: You are the vehicle, the gas, the map, but if the community isn’t in the driver’s seat, you won’t have the engagement or power to go anywhere.

Anytime, everywhere technology is an important tool for engaging your supporters. In the following chapters, we show you how social and mobile technologies help with advocacy, fundraising, and community building. The tools we cover provide communications options, collaboration spaces, and opportunities to make data usable and sharable. They can help you open up your data, employ a networked approach to collaborate and distribute actions, and work with your community and partners outside of formal campaigns to ramp up for the next push.

PUT THESE PRINCIPLES INTO ACTION

In the simplest terms, social and mobile technologies allow organizations to work with—not for—the community, which includes other organizations. We need to let go of the idea that we are simply serving our constituents, and recognize the ways that we can work together to change their neighborhoods or lives. When we use the “with” instead of the “for” perspective, we can see skills and contributions the community can make, opportunities for growth outside of our programs or our walls. We can see that we are part of a solution and not responsible for engineering the entire fix. We can then use social media, email, and mobile technology to elevate conversations, connect all those working together, and scale our reach and impact.

The following chapters will guide you through the ways you can put social and mobile technologies to use to engage, empower, and catalyze social impact. We return to these five principles throughout the book to highlight the strategic decisions, opportunities, and guidelines they offer to any organization. There are many case studies in the chapters that illustrate these principles in action, demonstrating how others have recognized the role of their community, selected tools, and collaborated with the help of technology—all to make real impact on our world.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

Spark a conversation with your team or organization about these core principles with the following questions:

NOTES

11. Additional Tumblr statistics and information from 2011 available at: www.businessinsider.com/tumblr-blows-past-15-billion-pageviews-per-month-2012-1

12. The “Rise Above Plastics” campaign images can be found at: www.surfrider.org/coastal-blog/entry/new-rise-above-plastics-print-psas-from-pollinate and the Campaign information at surfrider.org/rap

13. Komen Sues Over Use of Cure and Pink: www.huffingtonpost.com/2010/12/07/komen-foundation-charities-cure_n_793176.html