8

I Can See What You Didn't Say

It is our responsibility to learn to become emotionally intelligent. These are skills, they're not easy, nature didn't give them to us—we have to learn them.

—DR. PAUL EKMAN

When I wrote my first book, Social Engineering: The Art of Human Hacking (Wiley, 2010), I was relatively new to the world of nonverbals. But I had started a relationship with Dr. Paul Ekman and learned from him as my mentor. Dr. Paul Ekman started his journey to understand nonverbals in the late 1950s, and for the last 60-plus years he has been leading the field of research into nonverbal communications.

Dr. Ekman helped me refine not only my work, but also how I communicated. That led to my second book, Unmasking the Social Engineer: The Human Element of Security (Wiley, 2014), which delves deep into facial expressions, body language, hand gestures, and every aspect of nonverbals. I even cover the part of nonverbal communication you don't see: the hijacking of the amygdala.

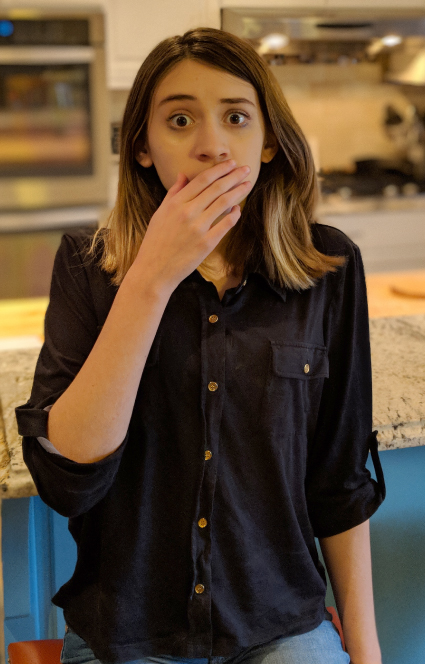

If you followed, read, or listened to any of my work before, it is probably not too hard to believe that when it comes to Dr. Ekman, I pretty much react like what you see in Figure 8-1 when I am around him.

Figure 8-1 What most people imagine I do when I see Dr. Ekman (not far from the truth).

PHOTO SOURCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elvis_Presley_-_TV_Radio_Mirror,_March_1957_01.jpg

I have a few goals with this chapter. First, I want to make sure I uphold Dr. Ekman's high standards of ensuring everything I say can be backed up with research. Second, I don't want to just duplicate either of my previous books, especially if you have read one or both of them. In this book, I present nonverbals from one key area that can literally change your life as a social engineer: the understanding of baseline changes between comfort and discomfort.

In this chapter, I smash any preconceived false notions you have had about certain body language tells and show you what exactly to look for as a socia engineering professional.

Nonverbals Are Essential

Before I get to the meat of this chapter, let me help you see why it's important to understand how to read nonverbal communication. Of course, the best way to do this is to tell a story.

When I was working with Dr. Ekman on Unmasking the Social Engineer, his role was to make sure that what I was saying was scientifically accurate, made sense, was logical, and was approved via his decades of research.

I had written a chapter about one study that had been done on mirror neurons. The study basically stated that the researchers believed there was a group of neurons in the brain that had the role of mirroring the nonverbals they see from other people.

Based on research from Dr. Ekman, we know that when we feel an emotion, we have an involuntary reaction, and that reaction is displayed by microexpressions. In addition, when we make facial expressions, we create the emotion attached to that expression.

I made the connection that if mirror neurons make us mirror someone's expressions—which are accompanied by emotions—we can control emotional content of our targets.

While I was writing Unmasking the Social Engineer, there was a scientific debate going on over mirror neurons and the research behind it. Consequently, Dr. Ekman wrote me a very nice email in which he basically said, “Do you want your book to have outdated or disproved research in it if this research gets quashed?”

I responded with, “But, but, but … I already have, like, 40 pages written all about it. And the chapter is due in five days.” I hoped Dr. Ekman would basically respond, “Okay, that's cool.”

Instead, he said, “Well, then I guess you have five days to read this research here on the amygdala and write a chapter on that.” And with that, I had about 60 pages of information on something I could barely pronounce to research, understand, and write about.

Of course, Dr. Ekman helped me greatly, but there was a lesson or three in this for me.

- It is important to understand how things work if I am going to truly help my clients.

- It is important to adapt and grow with new research.

- Sleep is really underrated.

While writing that chapter on amygdala hijacking, I again saw a connection in the research between planting emotional content and controlling a target's response. If the amygdala processes emotional stimuli before the brain has a chance to “turn on,” and I can cause the target to feel slight sadness or fear, then I can take advantage of their empathetic response.

In other words, mastering the use of pretexts can help me elicit the emotions I want in my subjects; I can make them feel how I want them to feel. Now we are getting to the point, finally, of why understanding nonverbals is so important.

When I'm about to break into a place as part of a job, or I'm about to do some vishing, I feel some pretty intense fear: fear of failure, fear of being caught, fear of messing up. Let's examine the emotion I feel.

How does fear affect me physiologically?

- My eyes are open wide and my eyelids are tense.

- My mouth pulls back in an “eek” shape, and I take in sharp breaths.

- My muscles tense and often freeze as I prepare for fight or flight.

- My heart rate elevates.

- My sweat production increases.

Now, let's discuss what my physiological state should be to elicit the desired emotional response from my target (which, as I previously mentioned, would be slight sadness to elicit empathy:

- My eyes are soft and not tense.

- My lips are turned down at the corners.

- My head is lowered.

- My muscles are not tense.

- My breathing becomes shallower.

Do you see the difference? If my pretext is using the emotion of sadness, but my body language is showing fear, what happens to the target? I would guess that the majority of people will never think, “Wow, this person is using a sadness-based story but showing fear. That is incongruent emotional content, which makes me feel uneasy.” However, we all have internal radar that tells us when we feel (or should feel) like raising the shields and being more defensive. If I showed fear but tried to elicit sadness and empathy, my target's radar would throw up that shield.

A truly phenomenal study titled “Chemosensory Cues to Conspecific Emotional Stress Activate Amygdala in Humans” (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2713432) proves this in an … uh … interesting way.

The researchers collected sweat pads from folks who had exercised. Then they collected sweat pads from a group of people who had jumped out of a plane at 13,000 feet in a tandem skydive. Then the researchers tested a group of subjects by attaching an fMRI to their heads and having them sniff each of the sweat pads. (Gross, but true.)

When this test group sniffed the sweat pads from the group who had jumped from a plane, the subjects' fear center, namely the amygdala, was triggered. When the subjects sniffed the pads from the exercise group, no fear was triggered. So, the old adage that you can smell fear is actually true.

Now that we know that other people can sense our fear, let's think about what I need to do as I get ready to approach a target. I have two choices:

- Learn to control my fear so I can display the proper emotion.

- If that is not possible, build a pretext that uses my natural emotion.

Understanding this can help you have a better grasp on your emotions to know what you're displaying and learn how to use, read, and then react properly to emotions and the nonverbal products of those emotions as a professional social engineer.

Before I get into the details about nonverbals, you first need to understand how to interpret emotional baselines.

All Your Baselines Belong to Us

Being able to read someone's emotional content can truly enhance your communication ability. I want to focus on how observing changes in baselines help the professional social engineer.

Let me first define a baseline. Simply put, it's the emotional content you see being displayed at the moment you start observing. You are not looking to understand their lifelong baseline. So, breathe—I'm not asking you to stalk your targets for months or years before each test.

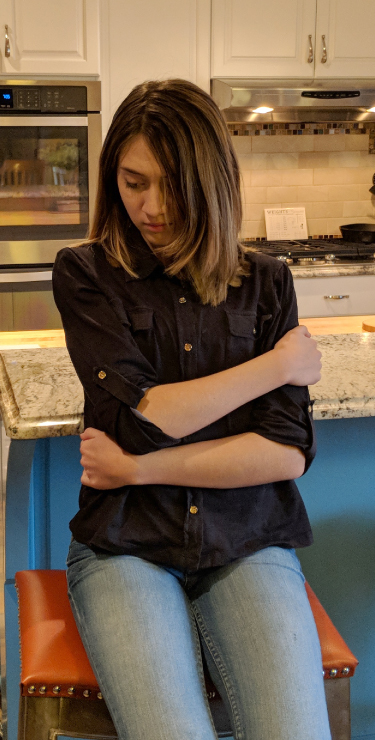

Look at Figure 8-2. Amaya did something that wasn't too great, and her mom is letting her know.

Figure 8-2 What baselines do you see here?

What do you observe? In Figure 8-2, what is the emotional content of my wife, Areesa? Do you see the tight jaw? The pointed finger and terse lips? She's signaling anger.

And what about Amaya? Her arms are folded, her chin is up in the air, and her face expresses irritation. She is closed off and not really in a listening mood.

Now look at Figure 8-3 to see what Amaya looks like after that “discussion” ends and Areesa and Amaya have parted ways.

Figure 8-3 What change do you see here?

Amaya looks a bit saddened and self-comforting. Maybe she's even reflecting on the argument.

Now look at Figure 8-4. Amaya and Areesa just got done enjoying a nice cup of tea and talking about their fun day of shopping.

Figure 8-4 What baselines do you see in this one?

What baselines exist here? Both look happy. They're leaning into each other and enjoying the conversation.

The three photos show the same people in different circumstances and displaying different baselines. Herein lies a very valuable lesson. A baseline is not a person's personality definition. It's not a psych profile. It doesn't cover the long term. The baseline is merely the emotional content being displayed at a specific moment.

Being able to read a person's emotional state at the moment you approach that person is vital for you as a social engineer. Your approach to target Areesa from Figure 8-2 to Figure 8-4 would have to vary greatly if you want to succeed.

Many times, I've have heard people say that they can be taught to tell the difference between lying and truth in a matter of seconds.

Dr. David Matsumoto, Dr. Hyi Sung Hwang, Dr. Lisa Skinner, and Dr. Mark Frank wrote an article titled “Evaluating Truthfulness and Detecting Deception” (https://leb.fbi.gov/articles/featured-articles/evaluating-truthfulness-and-detecting-deception) in which they make a very important point: “It is not the mere presence or absence of behaviors, such as gaze aversion or fidgeting, that indicates lying. Rather, it is how these nonverbal cues change over time from a person's baseline and how they combine with the individual's words. And, when just the behavioral cues from these sources are considered, they accurately differentiate between lying and truth telling.”

Do you clearly grasp their assertion? There's not some mystical tell that always indicates a lie or truth. How a person's cues change over time indicates the content of the emotion and way we should decipher it.

Be Careful of Misconceptions

People often hold some preconceived misconceptions about certain body language “tells” that you need to understand and get rid of before you venture down this road. If you don't, you'll end up making some bad assumptions.

Let's analyze some examples together. Look at Figure 8-5. What do you see?

Figure 8-5 Is Amaya upset or not?

For years, people have been told that folded arms are a clear indicator of being closed off. That is not necessarily true. If someone changes from an open display to a closed-off position as I approach, that might be true, but some people routinely sit or stand like with their arms crossed because it's comfortable and not because they are closed off. On both sides of Figure 8-5, Amaya's arms are folded, but her facial expression and position of her head indicate which emotion she feels.

Now look at Figure 8-6.

Figure 8-6 Is she irritated, about to lie, cold, or comfortable?

You can't see it in this still picture, but Amaya's leg was bouncing at about 500 beats per minute. Is this a sign of deception about to occur? Or maybe she is not comfortable? It's hard to tell. Some people just have busy legs or move a lot. Again, notice when a movement like this starts and observe how often it starts or stops to figure out what it means. Look at the whole picture in Figure 8-6: Amaya's body position, her leg bounce, her hand on the back of her neck. When you consider all the elements, you might decide that Amaya is looking uncomfortable.

My son Colin's leg is like a perpetual motion machine. I've always thought that if we could attach it to a generator, we could produce power for our home. He's not deceptive; he just moves a lot. Here is an example of how I used this knowledge about Colin's habits:

I said, “Hey, Colin, how did the party go the other night? Did you have fun?”

Colin, with his leg drilling a hole through the earth, would say, “Yeah, it was okay. Nothing too much.”

Now, in this case, I knew there had been a fight with Stewart, and I wanted to get details. I would say, “Oh, cool. Who was there again?”

Colin listed all the people there, but he left out Stewart. Hmm. I replied, “Oh, so Stewart wasn't there? I thought he was going.”

Now Colin's leg stopped dead, “Yeah, he was there too,” he said, as his leg started moving again.

“Oh. Is everything okay with Stewart?” I asked.

With his leg now firmly planted on the ground, Colin said, “Yeah, fine.” This time, there was a pause before Colin started to move his leg again.

The indicator that there was a problem was not that Colin's leg was moving, but that it had stopped. From there, it was a matter of a few seconds before I had the whole story.

Now take a look at Figure 8-7 and see what you can interpret.

Figure 8-7 Is this comfort or discomfort?

Face rubbing, scratching, or other types of manipulators can be indicators of discomfort, but sometimes people just have an itchy face. Notice when it starts and why.

I can use my son Colin for this example, too. He had asthma and allergies. There were many times when his skin itched all over. When it was pollen season, Colin was always touching or scratching his face. In this case, the fidgeting wasn't because Colin was lying but because of his allergies.

If we play into these misconceptions, we can fall into a trap of assigning emotional content where it doesn't exist. That can be dangerous because you can start to react to emotion that isn't there. You don't want to treat someone as if they are closed off when they are just cold, or assume that someone is being deceptive when their behavior is the results of having allergies.

The best way to combat this error is to approach each situation without using preconceived judgments, even if you're approaching a target you've interacted with before. Reserve your judgments for after the initial 15 to 20 seconds of the encounter.

When it comes to body language, I try to focus on the changes from baselines and then look for a change that indicates comfort versus discomfort. In Unmasking the Social Engineer, I wrote extensively about facial expressions and body language, so if you want to learn more about that subject, you can check out that book.

For this book, I want to give you just the basics of understanding the difference between comfort and discomfort. Once you have a clear grasp of what those indicators look like, you will have a map that tells you what to look for and how to decipher what you see.

Know the Basic Rules

This section covers four good rules for you to keep in mind when reading body language. If you apply these, you will see a massive difference in how you read and interpret body language.

These rules are not meant to be “math” in the sense that you must do 1 + 2 + 3 + 4, but they all must be done if you want to master reading nonverbals.

Rule 1: Focus on the What—Not the Why

This rule is straightforward: Don't make connections between the what and why without having all the information.

I often start off my nonverbal training day with helping students remember one thing: “Just because you can see the what does not mean you know the why.”

Think about this: While I'm speaking to the class, I say something as I make eye contact with you. I notice you fold your arms, your eyebrows go down while your eyes remain open, and your jaw tightens. I notice tension in your arms and hands. All these signs point to anger or discomfort.

I can assume you're feeling angry or uncomfortable about me or something I said. However, maybe you're reacting to pain you just felt because of surgery you had last year. Or maybe you have a stomach cramp that made you angry. Or maybe you weren't even paying attention, and you thought about something that made you mad.

Regardless of the reason for your body language, how do I connect the what to the why? As I discuss in Chapter 7, “Building Your Artwork,” it's all about questions. In a classroom scenario, it's not appropriate for me to stop my lecture to enquire about why you looked angry.

Rule 2: Examine the Clusters

When you start to practice engaging with targets, it's easy to look at one particular body-language movement or facial expression and think you can understand what is being communicated. However, focusing on one cue is dangerous. You need context and other body language cues to indicate what is really being said. Look for matching nonverbal clusters that indicate what emotion is being displayed.

Consider this scenario: You're talking to your spouse and telling them that you disagree with a decision. As you're stating your opinion, your spouse folds his or her arms. Does this automatically mean they are shut off, angry, or not liking what they are hearing?

Expand your view a bit. Do you see anger on your spouse's face? Do you see a change in the placement of their hips and feet, so that they're now pointing away from you? What are the other emotional “clusters” that can help you to pinpoint if the arm-folding was an isolated movement or part of a larger emotional tell?

Rule 3: Look for Congruence

Look for congruence between verbal and nonverbal communication. If someone shakes his head no but says the word yes, those two indicators are telling you that things are not congruent.

When you identify a lack of congruence in the information you perceive about someone, rely on the nonverbal messaging to indicate what is truly being said. Examining the nonverbal clusters and looking for a lack of congruency between nonverbal communication and the verbal communication. will help you get very close to accurately reading what the target is telling you.

Rule 4: Pay Attention to the Context

Let's say I look out my office window and see my daughter sitting outside. She has made herself small, sitting almost in a ball. Her arms are folded across her chest, and her chin is down. Her head is tucked low into her folded arms. All of these are signs of sadness and discomfort.

What I didn't tell you is that it's only 35 degrees Fahrenheit outside, and she was not wearing a proper jacket.

In context, you understand that Amaya is cold. Without the contextual detail about the temperature, she seems sad and uncomfortable. To avoid misreading the nonverbals, you must understand the context of the situation your target is in.

In addition to these four rules, there are some body language basics you need to know before I get into details about each emotion.

Understand the Basics of Nonverbals

There are some basic things that you should understand as you start down the path of nonverbals. These basic characteristics are applicable to all humans and not tied to a specific culture, gender, race, or religion. Understanding these basics will help you to understand how our bodies communicate exactly what we are feeling regardless of what we are trying to display.

External stimuli come into our brain through our five modalities, assuming one is not damaged: sight, smell, taste, touch, and hearing. These stimuli are processed by our brains, and the stimuli can trigger one of the seven base emotions: anger, fear, surprise, disgust, contempt, sadness, or happiness. The emotion that is triggered creates physiological responses in both our faces and our bodies.

For example, when a person is confident, they make themselves bigger, which elevates testosterone and decreases cortisol in the blood, according to a study titled “Postural Influences on the Hormone Level in Healthy Subjects” by researchers R. S. Minvaleev, A. D. Nozdrachev, V. V. Kir'yanova and A. I. Ivanov. (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023/B:HUMP.0000036341.80214.28). The researchers wanted to test whether certain yoga poises increased or decreased cortisol, testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and aldosterone. For our purpose, let's focus on cortisol and testosterone.

The researchers found that just by holding certain poses that are associated with confident behaviors, a person's testosterone increased by more than 16% and their cortisol dropped by 11%. Coincidentally, testosterone is known to increase behaviors that would be associated with a confident person. So, almost as a self-fulfilling prophecy, it appears that holding confident poses releases chemicals that help you feel and act more confident.

In essence, what is important for you to understand is: It appears that comfort-based nonverbals assist in creating happy, confident, and strong chemical and physiological reactions, whereas discomfort-based nonverbals can create stress, anxiety, and negative emotion–based reactions.

It is important to understand how certain nonverbals can affect both you and your target. As a professional social engineer, you are influencing or manipulating the emotional content of your target. Do not take this lightly.

Because the effect of your pretext on your target can be short-term or long-lasting, it is important to plan your pretexts carefully. Remember the motto: Leave them feeling better for having met you. Whenever possible, try to use pretexts that trigger emotional content that will not have a long-lasting, damaging effect on your targets.

How can you determine if the pretext you choose might have long-lasting negative effects? Try to determine what emotion you are basing your pretext on. Fear, anger, disgust, and contempt are so strong as negative emotions that you risk a greater chance of leaving the target damaged for having met you.

For example, there is a difference in a phish that says, “Thank you for your recent order of this 55-inch TV,” and one that says, “Your account has been hacked and your bank account has been emptied.”

Understanding that nonverbals and emotions can affect the target profoundly should help you determine how to use these emotions during your social engineering gigs. To this effect, one of the most profound lessons I learned from Dr. Ekman is that not only does having an emotion trigger a nonverbal response, but if you were to force the nonverbal on yourself, you can trigger the emotion. This concept was backed up by numerous researchers, including in a study titled “Inhibiting and Facilitating Conditions of the Human Smile: A Nonobtrusive Test of the Facial Feedback Hypothesis” (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3379579). Researchers Strack, Martin, and Stepper tested Dr. Ekman's hypothesis from the 1970s and 1980s and were able to show that if you create the expression, you can trigger the emotion. They did this by asking subjects to put a pen in their mouth to trigger muscular usage that simulated a smile. They were able to prove the same thing that Dr. Ekman stated in his research: Creating the facial expression (even by force) creates the emotion associated with it.

The key point to remember is that if you create an emotion, or you cause the target to express that emotion, you can leave the target feeling that emotion. You have to exercise caution when using this super power.

Comfort vs. Discomfort

It is important to learn how to communicate effectively, and part of that communication is nonverbal. There are some researchers who have developed statistics about how much of what we say is nonverbal. I have heard 80%, 85%, and even 90%, but one of the things I learned from Dr. Ekman was that, even though we can all agree that a large percentage of communication is nonverbal, the method of communication (spoken, written, in person) affects the way nonverbals are used.

What our bodies and faces show during normal communications can be overwhelming to people who can recognize the emotion being displayed. During normal communication, a person's body and face can display a myriad of emotions, and trying to interpret them can be overwhelming. For this reason, when you first start out as a social engineer, it's best to focus on the nonverbals that are the easiest to interpret: comfort and discomfort.

For this book I am trying something I haven't tried in my other books. I'm coming at this topic from the angle of the emotion and then discussing whether you, as a social engineer, would want to trigger this emotion in your targets. I explain how to look for signs that could indicate the comfort or discomfort displays that are associated with that emotion. I've divided this section by each emotion and described some of the indicators of that emotion in the face and the body. This is not meant to be an exhaustive list of every movement, but it provides a foundational basis for you to build on as you practice and begin to master this skill.

In addition to studying this section to learn how to read body language in others, you should use this information to learn how your body language can affect your targets. If you are displaying the emotions that I describe in this section, then you can trigger those emotions in others. Decide what emotions you want to trigger, and then practice the nonverbals for those emotions. Also learn to recognize the emotions and triggers that you do not want to elicit in others.

Anger

Anger is a strong emotion that has been labeled as a gateway emotion. What this means is that many times, anger leads to other emotions, feelings, or actions. Those actions can range from using expletives or angry words and escalate all the way up to exhibiting violent behavior.

Physiologically, anger makes us tense, tight, and ready to fight or defend. Muscles tense, the jaw tightens, and the person might clench their fists—all in a preparation for a fight or defense. As the person gets closer to taking a violent action, you might even see their chin lower in a protective measure to protect the neck.

Although things are tense and tight, you might notice a person who is experiencing anger try to make themselves larger. For example, an angry person might expand their chest, square their shoulders, and widen their stance. In addition, their breathing deepens and their heart rate increases.

Someone who is angry has the following facial characteristics:

- The brows will furrow, but the eyes don't squint. They open wide.

- The jaw tightens.

- The teeth clench, or, if the mouth is open, the person is often not saying pleasant things.

You can see all of this represented in Figure 8-8.

Figure 8-8 Anger in the face

Anger can also be displayed in the rest of the body. Figure 8-9 shows me with a tight jaw and clenched fists. In addition, my chest is puffed to make me look bigger. All of this points to anger. (FYI: This is the very picture I will hand to any boy that shows interest in Amaya.) If you notice any of these signs as you approach a person, it might be best to avoid that individual.

Figure 8-9 Anger in the body

Another version of anger is shown in Figure 8-10, in which Amaya is displaying subtle anger. Her glare, tight jaw, and slightly furrowed brow are all signs of anger.

Figure 8-10 Subtle anger

Most likely, you can figure out that anger is a discomfort nonverbal. It's one that I particularly do not like to elicit in my targets. Consequently, I watch for signs of this emotion and try to not use it in my engagements.

Many times, if I am too aggressive in my approach or if my pretext is too negative, I can catch signs of anger. It is a great warning sign to back off and to soften my voice or body language to alleviate some of the anger feelings in my target.

Disgust

Disgust is also a very strong emotion. Disgust can be felt toward a person, place, or thing. Oftentimes, something that makes us have a very strong disgust reaction sticks with us for a very long time after we've been exposed to it.

When I was a young boy, my parents raised chickens. I would love to run out to the hen house, grab a couple fresh eggs, and make what I intelligently called “egg in bread.” It was simply a piece of buttered bread in a pan with an egg in the middle.

One day, I grabbed my egg and cracked it open in my super-heated cast-iron pan. What came out was not a fresh egg but a half-formed chick. As it hit the pan, it started to flop around as it died. The sight and the smell made me heave into the sink. Because I was so disgusted, I forgot to shut the burner off, so the poor thing roasted, and the smell of burning chick filled the kitchen.

The disgust emotion that was triggered was so strong that even a decade later, the smell of a cooking egg would make me instantly feel sick. Eventually, I did get over that, but disgust is such a strong emotion that if you trigger it in your target, you might not be able to recover.

Think about the things that can trigger a disgust emotion in your targets: body odor, bodily functions, food on your face or in your teeth, foul language, word choice, and so on. It's important to carefully analyze your approach and yourself before you approach so you don't cause your target to feel disgust.

Disgust is exhibited a few different ways. On the face, it is a bilateral expression, meaning that both sides of the face show the same expression, as illustrated in Figure 8-11.

Figure 8-11 Disgust

As we were prepping for the pictures, my dog had done something nasty in the living room. I couldn't pass up the opportunity, and I captured a picture of Areesa cleaning up. Notice how the sides of her nose are raised, which blocks both the olfactory sense as well as the line of vision. In essence, she's physiologically blocking the things that are causing her disgust.

In the body, a person demonstrates disgust by blocking or turning away from you. Look for signs of a lack of interest or repulsion.

Notice the leg position of Amaya in Figure 8-12. Where is her interest? It's definitely not in her dad (as sad as that makes me). And although she's not showing a strong sign of true disgust, her body language is showing signs of discomfort and disinterest.

Figure 8-12 Disinterest

Because disgust is such a strong negative emotion, I tend to not use it during engagements. However, I have been asked about using it to create a tribe of people who are disgusted at the same thing. Although this can work and be very powerful, it can also lead to some dangerous results if not handled properly.

Contempt

Contempt is a unique emotion. The Oxford English Dictionary defines contempt as, “The feeling that a person is worthless.” Dr. Ekman offers a simpler definition, stating contempt is the feeling of moral superiority.

According to Dr. Ekman's definition of contempt, it can be felt only toward a person, and it is the only unilateral expression, which means it's shown on only one side of the face. At first, contempt may appear to be a smirk, or even the start of a smile, as shown in Figure 8-13.

Figure 8-13 Contempt can be confused with happiness.

Contempt is characterized by one side of the face being raised—for example, the corner of the lips is raised on only one side as in Figure 8-13. It is not uncommon to see this accompanied by a chin raise, even if it's only slight.

Because contempt is a feeling of being superior to another person and can often be a gateway into anger, you may see the following types of body language with contempt:

- Feeling superior to another person can make someone feel confident. That feeling of confidence can be displayed in several ways, but oftentimes, the person takes up more space by making him- or herself bigger.

- If the contempt has led to anger, you might see the same body language as I described in the previous section. However, before those anger nonverbals are fully displayed, you may notice a tightening of the jaw and more aggressive posture.

In my opinion, contempt has little to no use in a professional social engineering engagement. I can see how a nation-state might use it, and I have seen how it is used by terror organizations to recruit and then convert people to their cause, but for most standard social engineering engagements, it wouldn't lead to a desirable outcome.

Fear

Fear has many purposes, such as it alerts us to danger, but it can also be exhilarating and enjoyable when controlled. Some people even enjoy being scared or feeling fear.

Fear of disappointment, fear of failure, or fear of making the wrong decision can be useful for a professional social engineer, but I generally steer clear of stronger uses of fear. Pretexts that literally threaten or scare a person—such as those that cause them to fear for their jobs, lives, or families—trigger such strong emotion that when they find out they were being tested, they can be left with disgust or contempt, followed by anger.

Fear has some clear physical characteristics:

- The eyes are open wide to take in the whole scene.

- The body tenses, and there is usually an audible gasp of air.

- The mouth is open, with the lips pulling back toward the ears as if the person is saying “eek.”

You can see these characteristics in Figure 8-14.

Figure 8-14 A classic fear expression

In the body, fear has manifestations similar to the facial expressions. The body pulls back, tenses up, freezes, and prepares for fight or flight. If you startle your target, you might see the person react as depicted in Figure 8-15.

Figure 8-15 Startled fear in body language

Notice how Amaya has reeled back with her whole body tensed. Her mouth is in that “eek” position. This type of fear can be intense because there's no physical way for her to flee. She's cornered in her chair.

Figure 8-16 shows another aspect that we see in fear when displayed by women—covering the suprasternal notch.

Figure 8-16 Covering the suprasternal notch indicates fear.

Watch for subtle body-language indicators that can clue you in to how the target might be feeling. If you see signs of fear, you can then decide whether the fear being displayed is appropriate and how far you are willing to go to use it. As I mentioned before, I use fear as a professional social engineer, but I steer clear of the type of fear that can leave the target feeling threatened or in harm's way.

Surprise

Surprise is often confused with fear because it looks so similar. With surprise, the eyes open wide, as they do in fear. The body generally freezes and the mouth also drops open. But instead of opening with an “eek” shape, the mouth opens in more of an “OHHHHH” shape. You can see this in Figure 8-17.

Figure 8-17 Surprise, which can often be misinterpreted as fear

Surprise can be useful to a professional social engineer, but, as with some of the other emotions I've mentioned, it depends on how you use it. I don't suggest hiding in a closet and then jumping out to surprise your targets, but a surprise audit, visit, or reward might work to elicit the right response. In one engagement, which was solely a vishing engagement, I used a surprise reward to get some amazing results. The call went something like this:

| Target: | Hello, Beth speaking. How can I help you? |

| Me: | Beth, this is Paul from HR. I have some great news. You may not have heard, but we entered your department into the drawing for a brand-new iPhone, and your name was picked! |

| Target: | Come on! You're kidding! This is amazing! |

| Me: | I know. I love these calls. We're giving 10 away, and these calls have been a lot of fun. |

| Target: | Yeah, I never win anything. This is amazing! |

| Me: | As you know, we have a few Beths here at XYZ, so I need to verify some details with you to ensure that I have the right Beth. Can you spell your full name for me? |

| Target: | E-l-i-z-a-b-e-t-h S-m-a-r-s-t-o-n. |

| Me: | Excellent. I need your employee ID to enter it into the system. |

| Target: | T238712P. |

| Me: | Okay, you're the right Beth. Now I need you to go to a site where you'll be asked to log in with your domain credentials, and you'll tell the site where you want the phone shipped, etc. Go to iphone.company-website.com. [This was a website we set up that did nothing; none of the buttons worked.] |

| Target: | Okay, the site came up. I see our logo, but when I click the Enter button, nothing is happening. What do I do? |

| Me: | Hmm, I am on it now. When you click Enter, it doesn't go to another screen? I see another screen right now. |

| Target: | No. I'm trying a different browser. [Tried every browser she had.] Figures; I win something and can't even claim it. |

| Me: | No, we won't stand for that. Look, I'll claim it for you. Do you want me to enter your information? |

| Target: | Really? Would you do that? |

| Me: | Of course, I would. [Feeling as guilty as a snake.] It's asking for your full name, which I have… .” [I say each letter as I fake typing it in.] Okay, hitting Next. It wants your employee ID—you gave me that, so I'll enter that now. |

| Target: | Thank you so much. This is so cool. |

| Me: | Okay. It wants your domain login, which I assume is just E.Smarston? |

| Target: | No, I actually have it as B.Smarston. For Beth … |

| Me: | Okay, great. Now the last thing I need is your password. |

| Target | [without even pausing for a second]: I do really good with long passwords. It's “JustinandBeth99”! |

| Me: | Excellent, that worked. It says you'll get an email within 24 hours with further instructions on what to do to claim the phone. Congratulations, Beth! |

| Target: | Thank you so much! |

With that, we had a full compromise of the network. Yes—for all of you who are preparing your hate mail—that was manipulative and used a pretext that made the target a little upset when she found out about it later. But, remember, I didn't threaten her; I didn't embarrass her; I didn't cause her harm. I used a surprise to trigger a happiness-based emotion, and that led her to give all sorts of information to me without thinking.

From a body-language perspective, there are a few things that you may notice that indicate surprise. These are shown in Figure 8-18 and Figure 8-19.

Figure 8-18 Surprise may cause a person to lean back with raised facial expressions.

Figure 8-19 Shock, a form of surprise, might be indicated by a person covering their mouth.

In my opinion, surprise is a good emotion for a professional social engineer. With the proper planning and execution, it can lead to large victories for you.

Sadness

Sadness is a very complex emotion. It also has a huge range, as it can span from feeling slightly blue to utter despair. As a social engineer, there are a few ways that you can use sadness:

- Noticing sadness in a target and then using that emotion to elicit a reaction

- Creating a situation that will most likely cause the target to feel sadness and lead to them to react the way you want them to

- Displaying sadness in your own nonverbals to elicit an empathy-based response

Some of these methods employ a more manipulative approach than others. It all depends on how you employ these emotions and what the resultant emotional state of the person you use this on.

Sadness has a few facial indicators, which are demonstrated in Figure 8-20.

Figure 8-20 Facial elements of sadness

On the face, sadness is shown by

- The corners of the mouth turning down

- The eyelids drooping

- The corners of the eyebrows coming together and going up

In some extreme cases of sadness, you can read the emotion from just one part of face.

Sadness can also be conveyed by a person's body. Sadness makes us want to protect, comfort, and become smaller—the opposite responses of feeling confident.

Some examples of self-comforting nonverbal displays are shown in Figure 8-21, Figure 8-22, and Figure 8-23.

Figure 8-21 Self comforting hug

Figure 8-22 Eye blocking

Figure 8-23 Slumped body language

This is a short list, but you get the idea. These nonverbals can help you see that the person is feeling definite discomfort.

Sadness, in all of its complexity, can be very useful for a social engineer—both in learning how to read it and displaying it. However, I caution you to temper how you use this emotion and to what level you use it in your pretexts.

I never want to leave my targets with an overwhelming feeling of sorrow or grief, but using the proper level of sadness can elicit a strong empathetic response. In a study conducted by Jorge A. Barraza and Paul J. Zak titled “Empathy towards Strangers Triggers Oxytocin Release and Subsequent Generosity,” (https://nyaspubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04504.x), the researchers showed that there was a 47% increase in oxytocin release when empathy was triggered, even when the empathetic feeling was between complete strangers, whereas sadness can create a lack of serotonin, dopamine, and oxytocin in the brain. As a professional, I try to stick to the empathy side of sadness instead of the worry, grief, or depression side of the spectrum.

Just think about how many times this tactic is used in marketing and charity drives. From homeless children to abused animals, the goal is to trigger an empathetic response to encourage you to more easily decide to part with your money. This doesn't mean those organizations are being dishonest or manipulative—they just know how our brains work, and it helps them achieve their goal.

Happiness

Happiness is one emotion that we can all agree is very useful to all human interactions. When we feel happy, content, at peace, or relaxed, we are more prone to make more altruistic decisions. We tend to like the people, places, or things that make us feel this emotion.

For that reason, it is easy to see that, as a social engineer, happiness would be one emotion you want to master reading and eliciting. The first thing that can really help you to see if you are doing a good job and creating happiness is learning to identify the difference between a real smile and a fake smile. The one thing that separates a real smile from a fake smile is the activation of the orbicularis oculi muscle. When triggered, this muscle raises your cheeks and forms what we call “crow's feet” around the eyes.

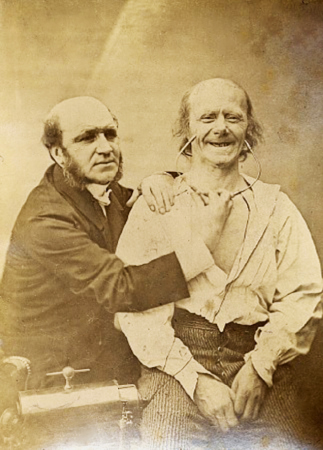

In the mid-1800s, a French researcher named Guillaume Duchenne postulated that a real smile could be faked. He was studying neuroscience with the use of a very invasive form of electroshock. He administered shocks to stimulate muscle movement (www.thevintagenews.com/2016/05/07/44782-2).

Due to the pain involved, Duchenne did not get too far with this research, but his research into how emotions were displayed through facial expressions showed that the face is a roadmap to emotion. Around 1855, he developed a method to use electroshock stimulation to trigger muscular response, and he wrote about his findings in Mécanisme de la physionomie humaine. The result was what you see in Figure 8-24.

Figure 8-24 A fake real smile

PHOTO SOURCE HTTPS://PUBLICDOMAINREVIEW.ORG/COLLECTIONS/THE-MECHANISM-OF-HUMAN-PHYSIOGNOMY FROM MÉCANISME DE LA PHYSIONOMIE HUMAINE

Reading about this research can help you understand why happiness produces the facial expression known as smiling. But as a professional social engineer, you need to learn to recognize other body-language indicators of happiness.

How is the emotion of happiness displayed by a person's body language? If happiness releases strong neuro chemicals and creates a confident environment, then we can expect to see certain body expressions, too. Look for body postures like those shown in Figure 8-25, Figure 8-26, and Figure 8-27.

Figure 8-25 Notice the open, confident arm position.

Figure 8-26 Open ventral displays indicate trust and happiness.

Figure 8-27 Open ventral displays are often associated with welcoming or cordial greetings.

On the face, we look for the eyes to be engaged in the smile in addition to the mouth forming a closed- or open-mouthed smile (see Figure 8-28). Many times, people who feel happy also lean in toward the object of their happiness.

Figure 8-28 Happiness on the face shown by a genuine smile and head tilt

Other signs of happiness might include things like raising the toes or bouncing on the balls of the feet. When people feel confident or good, they tend to make themselves bigger or bounce more.

Happiness is one of the emotions I look to use frequently as a professional social engineer. Appealing to a person's ego is a great way to create happiness that can lead to an emotional decision. For this to work, though, the ego appeal must be realistic, believable, and appropriate to the level of rapport you have built at that moment.

I find that, if it fits my pretext, approaching a target with open ventral displays and a warm smile with a proper head tilt can go a long way in making the target feel comfortable with me.

Look for ways to create a happy environment in your social engineering pretexts, and you will be rewarded with good results.

Summary

Nonverbals are a complex and huge topic that I realize can't be covered in a relatively short chapter. As I mentioned in the outset, my hope is that by going through a high-level overview of this information, you could walk away with a few different things in your arsenal. Understanding how emotion works will benefit you for many pretexts. The more you understand about what someone is saying without using words can help you to understand their communications much more clearly. Here are the main ideas that I hope you take away from this chapter:

- Foundational Tools As a starting point, this chapter can help you learn what subtle things to look for in the face and body for each emotion.

- Better Understanding I hope you have a better idea of which emotions will work for you and how to not only see those emotions in others but display them yourself.

- Defense Understanding how emotions are conveyed through facial expressions and body language can also be very helpful for you as a defense mechanism. Realizing how these emotions can and are being used will make you more aware when they are being used against you.

- Enhancement As a professional social engineer, it is essential for you to always be learning and enhancing your skill set.

I want to tell you one more story about social engineering that might help solidify the ideas of this chapter. During one DEF CON, I had an interaction with an employee that helped me see how important it is to be observant of nonverbals all the time.

The conference is always a busy time for me and my team. I feel like I rarely get a break or even a few minutes to myself during those five days. I just flip the switch “on” and leave it there as I feed off the energy and positive vibes from the crowd.

This is powerful for me, but it can also make me unaware of others' feelings. I bounce around, barking out orders and making sure things are getting done. At this one conference, I had given a few orders to some of the employees to get things packed up. It was our last day, and we were rushing to get everything organized so we could go out and have our final team dinner at our favorite sushi place.

Things were going smoothly; everything was running 100% perfectly. We needed to do the closing ceremonies, and then we could finally decompress. I was trying to be more aware of others' emotions, and I noticed one person's face registered not just fatigue but utter exhaustion. Another person was expressing some serious distress.

To the first person, I said, “Hey, if you are really tired, you know you can request to sit out of this part—you don't need to come to closing.”

“What? Really? I could have opted out?” he asked with utter surprise.

“Yeah, bro—I just thought that was a given. Sorry I didn't mention it before.”

“I had no clue we could opt out. I thought it was mandatory,” he said.

“Well, it's only mandatory for Michele. The rest—you can opt out.”

Then there was a huge sigh of relief from my employee.

When I approached the next person, I needed to be delicate. I couldn't call her out without creating problems in front of others. The emotion I was reading on her was a mix of sadness, anger, and fear.

I approached her privately, pulling her away from the group, and asked if she was okay. I won't describe the interaction in detail, but there were a lot of tears. She was feeling stress because she felt like things got dropped or ignored. And she was very stressed due to the lack of downtime.

So, I learned a new lesson. During that last day of the conference, I was being particularly observant and attentive to my team's emotions. However, I realized that I should have been using this skill throughout all five days of the conference to notice issues before we got to that level of stress.

Let me apply this story to social engineering: Be observant, but not just during the engagement. Look for “flags,” but also be observant during all communications. Be observant for changes in the baseline and for emotional leakage that can help you see what a person might be feeling before, during, and even after your interaction.

Being able to read nonverbals is a powerful skill. When you add the ability to use nonverbals to elicit emotions in your targets, you have achieved almost superhero level.

This concludes the chapters in which I outline the majority of the skills I use as a professional social engineer. In the next chapter, you'll learn how you can apply these skills to social engineering penetration testing. What vectors can these skills apply to? That is the very topic of the next chapter.