3. Games People Play

It is important for marketers to understand the influence of game theory on social location marketing. Although I have no intention of providing a complete psychology lesson in game theory, I do believe that without a chapter on the topic, this book would be lacking in its completeness.

Game theory is a subset of economic theory that attempts to offer explanations of interactions between human beings and between human beings and inanimate objects that surround them. Specifically, game theory attempts to use math to predict an individual’s behavior in strategic situations, or games, in which an individual’s success in making choices depends on the choices of others. These explanations are used across multiple disciplines, including economics, psychology, sociology, marketing, and market research.

As animals, human beings are inherently social. We like to group together for a number of reasons, including security, collaboration, and for the element of “fun” that human interaction affords us. We are, in fact, not alone in the enjoyment of fun; many other animals have been found to laugh and play games with each other. However, in this chapter and for the purposes of the book, I am going to confine myself to the role of game play and social interaction among human beings.

The point here is that game play is not something that has recently happened because of sites like Facebook or because of the advent of social location sharing. Human beings have always been social. Technology, however, has enabled us to play games with people who live across town, in another state, or even in another country. Whether it is with family members, friends, or work colleagues, proximity is no longer a requirement for the game to occur or for it to be enjoyed.

Although it is true that some games—chess for example—have been played remotely for years (I used to play with an Uncle via mail when I was growing up), technology has expanded the type of games being played, the appeal of those games to a broader audience, and has increased the instant gratification nature of the games being played.

So who actually plays games? In particular, who plays Internet-based, social networking games? A study by PopCap found that 55% of players in the United States and almost 60% of players in the UK are women. Of these women, the average age in the U.S. was 48 and in the UK 36. Interestingly, only 6% of all social gamers are aged 21 or younger.

Women are more likely (68% vs. 56%) than men to play online games with their real-world friends and twice as likely to play with family members as their male counter-parts. So are these people just sitting at home all day playing games? Actually, far from it. The truth is 41% of online gamers work full time and a total of 42% of those surveyed earn $50,000 per year or more. 95% of online gamers play multiple times per week, and 60% of them play for at least 30 minutes each time. Quite obviously, playing games is an important part of social networking for a significant portion of people who use social networking apps. Whether they are using iPhones to play Words With Friends or Facebook to play Farmville, playing games with others is an important part of the social networking world and something that should not be ignored by marketers.

However, there is more to it than simply seeing these game platforms as another media buying opportunity (though undeniably they present that opportunity). It’s important that you learn why people play games and how those games appeal to different genders and ages. This will allow you to build game play into your social location marketing campaigns and capture the true spirit of the apps that your customers are using to communicate.

For example, if the average online social gamer is a 38-year-old woman, earning $50k a year or more, does that mean this is your most lucrative marketing opportunity? What if your target audience is men aged 24–39; wouldn’t it make more sense to find a way to reach that audience instead?

Ultimately, knowing your audience—a theme I will return to many times in this book—is what determines whether using social location marketing is the appropriate channel for your organization. However, just because your audience isn’t the average user doesn’t mean that this form of communication isn’t relevant to them. In fact the Pew Internet and American Life Report recently revealed that men use social location sharing apps twice as often as women do. However, this statistic might have more to do with the fact that typically, men adopt new technology earlier than their female counter-parts do. Also, early incarnations of the social location sharing apps focused more on competitive behavior than they did on collaborative behavior. As you might guess, competitive behavior is typically more appealing to men, whereas collaborative behavior is more appealing to women.

Suffice it to say that with the introduction of Facebook Places, we can expect to see the number of women using social location sharing apps change over time—in fact, a very short period of time.

Note

![]()

Facebook is known for its strong appeal to women (see Brian Solis’s report, “In the World of Social Media, Women Rule,” where he highlights that Facebook has 57% female users vs. 43% male users). Given that more women use Facebook and that Facebook Places allows users to share their locations and more, it’s clear that we will see an increase in the number of women using social location sharing apps.

More than any other social network, Facebook has the capability to bring social location sharing into mainstream use by social network members. Even though Foursquare, Gowalla, and other social location sharing apps have huge user bases, we can expect the social location sharing concept to become more mainstream now that Facebook is a player. As social location sharing becomes more commonplace, marketers will have to be ever more aware of what elements make for good game play and what makes a campaign attractive to people using each of the social location sharing apps.

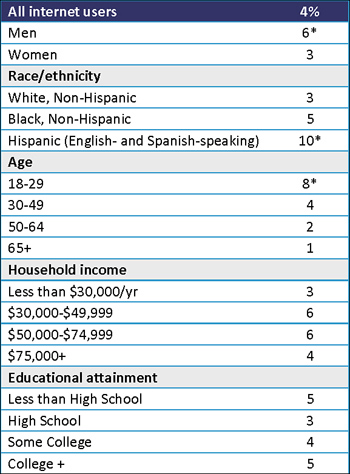

If we take a more detailed look at the Pew Internet and American Life Survey results, the current state of usage of social location sharing apps is quite surprising (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1. *Indicates a statistically significant difference. Zickuhr, Kathryn & Smith, Aaron. 4% of online Americans use location-based services. P3, Pew Internet & American Life Project, 11/4/2010, http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Location-based-services.aspx, accessed on 11/15/2010.

The survey shows that the primary users of apps such as Foursquare and Gowalla are young Hispanic males earning at or just above the average U.S. wage. This is probably not the target audience that a lot of marketers running social location marketing campaigns are targeting, and yet this survey tells us that is who is using these apps.

Note

![]()

This survey is the result of a 3,000-person population being interviewed in both English and Spanish.

Again this reinforces the point that knowing your audience is extremely important, and knowing the user base of the latest social communication channels is also crucial.

Anatomy of a Game Player

Game players are often described as falling into two main typologies: Classic and Romantic. Gamers have two very different approaches to how they take part in games and how they derive pleasure from game play. It is important to understand these two typologies and think about how they fit with your intended audience, campaign, and your goals for the campaign.

Classic—These players are driven by the need to minimize risk while maximizing their gains. They typically look for strategies that allow them to make advances in the game at every turn, even though those advances might appear minimal. Their primary goal is to advance their positions ahead of their original positions. Chess players are often considered to be part of the Classic typology. They study potential outcomes and seek to learn all possible resultant moves based on the move that they make. In this way, they have a sense of “knowing” in advance what their potential gains are based on their opponent’s response—whether that opponent is human or machine. They enjoy rule-based game play because this allows them to “learn” the potential moves as part of learning the game. They view this as essential to the game. They do not get the same from “emerging” games—where the outcomes are determined by what actions the user takes and what events unfold based on the actions of the user.

Romantic—The Romantic game player typology is most associated with high-risk takers. They seek to find the one decisive blow that will ensure their victory over their opponent. They are also likely to seek ways to intimidate their opponents and convince them psychologically that they have already lost, even if this is not the case. They are more drawn to emerging games than purely rule-based games. Poker players often fall into this typology because the “all in” mentality of risking everything for the ultimate payoff is a well-known display of the romantic game play.

Overachievers and the Easily Bored

The reasons people play games are as multitudinous as the people playing the games. These reasons range from boredom, escapism, killing time, socializing, competition, entertainment, status, and peer pressure—the list is almost endless. However, there are a few main categories that all these reasons can be bracketed by, and these tend to be divided by the driving force behind the gamer.

Serious Gamer

These are the gamers that spend hours on end locked in darkened basements, who have over developed thumb muscles, live on pizza and Red Bull, and wear headsets to talk to their gamer buddies (all of whom have extremely awkward sounding “in game” names). At least that is how the media would have you view them. Actually, many of these hard-core game players are professionals who use the game play as a form of steam valve. However, whether they hold to the media stereotype, they have one thing in common: hard work—or at least an expectation of hard work.

They expect to work hard, whether slaying ever more difficult monsters or solving increasingly complex puzzles, to advance to the next level. Their expectation is that they will be challenged and feel a sense of achievement at the end of each challenge. This is how they place value on the game that they are playing. If the game is too easy, they feel that they have wasted their money or time. If the game is too hard, they may move on to something else.

Casual Gamer

This is the type of gamer who plays when they remember to play. They aren’t particularly bothered by the challenges, though they like to have a sense of achieving something when the challenge is met. They are likely to either be noncompetitive players or be competitive only at the time of play (for example, they play to win, but do not remember the score the next day). They are more social in their game play and when playing with friends are more likely to be playing for the sense of bonding than for any sense of “beating” their fellow players.

Games that are easily picked up and dropped are ideal for this type of player. The smartphone game Angry Birds is popular for this very reason. Players can sit with it for hours and try and beat their own scores or those of other players. Or they can simply dip in to the game for a few minutes while they are waiting in a line. These are not game traits that would appeal to the serious gamer. However, they fit the casual gamer extremely well. Games designed for the smartphone user tend to fall into this category, and certainly campaigns focused on social location marketing would fit into this category as well.

Masters of the Universe

These are the gamers that, usually, fall into a younger age group. For them, mastery in the game world replaces the lack of control that they experience in their real lives. In the real world, they have to abide by rules set by parents, schools, and other authority figures. In the virtual worlds they can often rise to a level where they set the rules. They become “legends” among other gamers and garner a level of respect that eludes them in the real world.

This desire to have mastery over a game system also leads to the creation of cheats, because this type of gamer is likely to want to find ways—by any means possible—to beat the system. Foursquare experienced this early on when people were checking into places that they had not been in order to gain the “Mayor” status. The need to have the status without actually earning it drove this behavior.

Foursquare and the other app developers have gone to great lengths to ensure that this behavior is as limited as possible. In fact, Foursquare recently introduced a mechanism whereby venue owners can remove a user as Mayor if they believe that the user earned it in a way that was not legitimate. It is important that the campaign you create for a social location sharing app have some form of real-world validation—whether it is uploading a picture, performing a task, or interacting with staff. You should never rely solely on the game to validate a user’s participation.

Young Guns and Old Codgers

There is, rather unsurprisingly, a difference in the expectations of gamers of varying ages. Older gamers tend to want a journey on the way to the goal. They want to be a part of a story that unfolds through the game play, that draws them along, and that is something they can actually enjoy and feel connected to as they play the game.

Younger players tend to want to get to the destination—the “are we there yet” mentality that any parent who has ever undertaken a journey of longer than 10 minutes with a small child is all too familiar with. They are less interested in a detailed story, though context is important. They need to know why they are doing something, but they don’t necessarily need to be involved in an unfolding story. They want to know why the characters are there but they don’t want to be involved in their story unless it makes getting to the destination easier.

Interestingly enough, this same dynamic tends to generally divide the genders, with men being goal focused and desirous of an ending and with women being more story focused, enjoying the journey and less focused on the final outcome. Women also tend to want the opportunity to be collaborative in their game play. That means games that have stories that weave interaction with others into them are very attractive to them.

Again this is important to note when considering a social location marketing campaign. If the target audience is going to be women, what are you doing to ensure that they are going to get some of these needs met? If your audience is men, how are you going to ensure that they get to the goal in a fashion that provides a challenge but doesn’t consume a lot of their time?

Are We Having Fun Yet?

Nicole Lazzaro, founder of gaming design company XEODesign, has written extensively on the components of good game design, and I recommend that anyone who has a deeper interest in how video games are thought through read some of her work. Also Roger Caillois covers game categories in his book, Man, Play & Game. I also recommend this book as further reading on this topic.

Caillois and Lazzaro both define four distinct game types, and they have many similarities. Lazzaro defines four elements of fun and the emotions that they generate.

• Hard Fun—Generates emotions of frustration. The focus in this type of fun is on problem solving and strategy. This fits with our earlier description of the Serious Gamer who wants games to be difficult and who wants increasingly harder problems to solve. An example of this would be the online game World of Warcraft.

• Easy Fun—Here the focus is on curiosity. This type of game fun generates emotions of awe, wonder, and mystery. This fits with our description of the casual gamer, in particular the older and female gamer. They are looking for rich story environment, something that they can become immersed in but something that they can also leave at any point when other priorities take precedence. Trivia games, such as the Facebook game QRANK, fit into this category.

• Altered States—This is the sense of mastery that we referred to earlier: the escape from reality and the sense of excitement at that escape. This group wants the opportunity to exercise an increased sense of control over outcomes and to feel powerful among a peer group. Games such as Grand Theft Auto fit this typology.

• People Factor—Here the focus is on competition, sometimes with the help of others, such as working in teams to defeat others. The range of emotions in this type of fun includes schadenfreude (amusement at the misfortune of others), social bonding, and personal recognition. This applies quite well to Foursquare as a gaming app: the knowledge of “ousting” someone as Mayor of a location, the broadcasting of that message across personal social networks for others to see, knowing that in some cases members of that network will find it amusing to see the Mayor replaced.

Caillois defines his four types of game play in the following manner:

• Competition—In these types of games the pleasure is derived from overcoming the challenge of an opponent, of defeating an enemy, whether real or virtual. In addition, the development of skills necessary to win creates pleasure. Games involving strategy and those that include teamwork often provide this element, such as chess or physical team sports. SCVNGR certainly provides the infrastructure into which a marketer could create challenges that would meet this type of game play.

• Chance—Games that include the element of chance inspire the players to try to find strategies and methods of play that minimize the element of chance and to look for potential outcomes dependent on the inclusion of chance. In its most extreme form, players are in fact using an adaption of probability theory. Think of the movie 21, which was based on the story of the MIT Blackjack team, whose story was told in the book Bringing Down the House. Here, real math geniuses used probability theory to try to overcome the element of chance by counting cards.

• Vertigo—This corresponds to Lazzaro’s Altered States concept. These are gaming elements that provide a sense of disorientation or disconnection with the real world. Whereas Caillois cites activities such as skydiving or riding roller coasters as examples, virtual worlds, online games, and console-based games have been recognized for providing this type of sensation. Certainly games where the normal rules of life—those of physics, biology, and chemistry, for instance—are suspended, altered, or rewritten fall into this category.

• Make Believe—This is the sense of using one’s imagination. The ability to create scenarios and to control the environment are important in this type of game element. The player requires a strong element of control over how things will end. In addition, not everything should be shown to the players; they require the ability to think through a situation and discover, sometimes through trial and error, how to find the appropriate solution.

None of these elements are exclusive. Any game might consist of several of these elements at different stages. In fact it is important for certain types of games that they include several of these elements to ensure some form of longevity. For example, linear games tend to have a limited shelf life. Once a player has played through all the levels, killed the very last monster and solved the very last puzzle, then that game is put away and the next one is rolled out. Now compare that to something like chess.

A chess board, at face value, presents itself as being much less complex to master than a video game of multiple levels. But the chessboard is not put away to be forgotten after a game has been played. Quite the opposite occurs—games are replayed, and new challenges are issued. Players want the opportunity to face new opponents. The game pieces themselves are not the game, the players are the game. Each time the pieces are laid out, they hold the potential for a new outcome that is dependent solely on the players who control them.

This level of what marketers term “stickiness”—the desire for a user to continually return to the board—is what makes game play so important to social location marketing. It is important that you find the right elements for the campaign that fit the intended audience, that mesh well with the app that is being used, and that meet the needs of the campaign message. These are the key features of a well thought out social location marketing campaign that effectively leverages the spirit of game play.

Remember, each individual derives different levels of pleasure from different games, although this will depend on the type of gamer the user is. However, it is also true that different games offer different levels of pleasure. The psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihály (pronounced MEE-hye CHEEK-sent-m![]() -HYE-ee) outlined what he refers to as the “Flow”—a state in which game players become so involved with the game that all other considerations fall away. Users are involved in the activity simply for the sake of the activity. In this state, players use their skills to the utmost to remain inside the game.

-HYE-ee) outlined what he refers to as the “Flow”—a state in which game players become so involved with the game that all other considerations fall away. Users are involved in the activity simply for the sake of the activity. In this state, players use their skills to the utmost to remain inside the game.

Csíkszentmihály outlined eight elements that contribute to this state of “Flow”:

• Activity—Players want to feel the activity they are engaged in is one that requires skill. However, the level of skill is variable. It must be something that is at a level that the gamer already has or can see a clear path to achieving the skill in a reasonable amount of time. Also, the game must provide for some type of leveling. That is, if the player competes against the game system, it should start out as an even balance and become progressively harder. Imagine beginner chess players playing their first game of chess against a grand master. The result would be demoralizing for the beginners and they would likely give up on the game. Equally for the grand master, there is no challenge and so the game itself becomes pointless. A good example of this was the Jimmy Choo campaign “catchachoo” described in Chapter 5. It was relatively easy for users to take part, but people who were familiar with the area had a distinct advantage over newcomers.

• Concentration—The need to concentrate on what we are doing and therefore make progress in the game is something that has to be carefully controlled, especially with regard to social location marketing. Given that the apps run on smartphones and the environment in which a smartphone is used is usually one full of distractions, the amount of concentration required to succeed needs to be relatively minimal—especially if all the game play takes place on the phone. For example, players should not miss out on a reward simply because they were distracted by wait staff taking their order. This would engender animosity toward the brand, rather than loyalty. This is why extending the game-play beyond the device and into the environment is particularly important for social location marketing campaigns. Using the device as the gateway to the game rather than the gaming environment itself increases the possibilities for the marketer.

• Goals—Player must understand, from the outset, the point of the activity. Vague promises of a reward are not enticing. Concrete goals (for example, get to this level and win this) are much more motivational. Also, the goals have to be commensurate with the effort. As I will discuss in later chapters, if a user spends hours of time completing your challenges only to find that the reward is a free coffee, your campaign is likely to be met with derision, not praise. Think this through carefully when putting together the game play elements of your campaign. For example, the progressively harder challenges that are possible in SCVNGR allow the user to choose how much time she will devote to your campaign and therefore how much of a reward she is likely to receive.

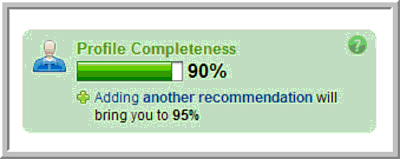

• Feedback—Everyone likes to know how he or she is doing. Think about the workplace. If you never get feedback after a big presentation at your annual meeting, think of the angst that creates for you. The same applies to games. Players need to know how far they have progressed and how much further they have to go. In game theory, this is known as the progressive dynamic. Often the simplest method for showing this is a progress bar.

Figure 3.2 shows a user how complete her profile is on a social networking site. It also shows her what actions she needs to take to reach the next level of completeness. This is a simple graphic, yet it is also surprisingly motivational.

Figure 3.2. LinkedIn Progress Bar

• Involvement—Being engrossed in the game frees the user from his other worries. The sense of escapism is an important element for many game players. It provides them the opportunity to focus their attention on something else and get away from the daily grind. The amount of time spent with a game will determine the level to which this is achieved. However, even the simplest of games—if they are absorbing enough—will provide this escapism.

• Control—The ability to control the environment in which we find ourselves is an overwhelming human need. Games—especially those of an electronic nature—often provide worlds in which the player can bring absolute control to the environment. Early examples of this were known as management simulators, which ranged from sports management games to city creation games such as Sim City. These games are still hugely popular and the strong element of control is a major factor in this enduring popularity for the genre. Farmville is also a game of this type. Farmville is played exclusively within the Facebook platform, and at the time of this writing, it has more than 85 million players—all of whom are competing to grow crops, sell them, and make a profit while fighting off the challenges of the environment and other elements outside of their normal control. The fact that the game requires work is overshadowed by the fact that it allows for the player to control other major elements within the game.

• Self-Absorption—The ability for a game to reduce the amount of self-absorption a player exhibits is another major factor in the success of a game. Players who are able to step away from themselves and concentrate on acquiring a new skill or develop an existing one find the game more rewarding than those who are not given this opportunity.

• Time Perception—Time flies when you are having fun, so the adage goes. This is especially true of a good game. The ability of the game to become so engrossing that the amount of time spent playing it is no longer of importance to the player is key to ensuring that the player will want to return to play again. This does not mean that the game has to take up hours for game play. In fact, a game that takes only a few minutes to play can become just as engrossing if the game play meets many of the other requirements.

Now that we’ve looked at several viewpoints on effective game design, it’s important that you are able to apply what you’ve learned here to your own social location marketing campaigns.

It is important to remember that any good social location marketing campaign will extend beyond the app itself. Simply relying on the game play contained within the app will not provide a sufficient enough reason for the savvy social consumer that uses these apps to want to engage with your campaign.

That means offering a free coffee to the mayor of your coffee shop no longer cuts it (even though this might have been an enticing offering 18 months ago when social location sharing apps were in their infancy). You must offer more—not just in the sense of the reward but in the game play that leads to the customer getting the reward. Even though this technology is still nascent, marketers are already fighting what is being termed “check-in fatigue.” Social consumers are asking “why bother?” They need a reason to take part. They need something more engrossing and that extends the experience of the location beyond their phones.

After all, your location, whatever it is, is more (or at least should be more) interesting than your customer’s phone. The idea is not to make your customers fans of Foursquare, Gowalla, Yelp, SCVNGR, or any of the other apps. The idea is to make them fans of your business and build loyalty with your location(s).

So building game play into your campaign that entices them and absorbs them while they are in your location is what will get them talking about your brand. Ultimately, this is what you are trying to achieve. Don’t lose sight of that.

From the elements I have identified in the previous section of this chapter, which elements fit best with a social location marketing campaign in terms of game play?

The Ingredients

Like any good recipe, the quality and quantity of the ingredients make all the difference. So it is for social location marketing campaigns. The following ingredients are all essential for your campaign to leave the right taste in the mouths of your audience.

• Skill—So far, we’ve clearly shown that an element of skill—whether the use and development of an existing skill or the acquisition of a new skill—is important to game players. They want to feel like they have gained something from playing and that they are better at something than other players. This could be a demonstration of their knowledge—for example, in a trivia-based game—or their ability to compose a photograph in a funny pictures competition. Whatever the competition, the inclusion of an element of skill is very important.

• Competition—Even though the research suggests that males respond more to games that have a strong focus on competition, that does not mean females are not competitive. They most certainly are; however, the degree to which this is important to the player is what varies between the genders, and so whether the target audience is male or female, your social location marketing campaign game play must include some form of competition and some form of showing how well a player has done against the competition.

• Concentration—The game should require attention. The player needs time to focus on the game. This is where extending your campaign to the real world and removing it from being solely based on the user’s phone allows you to remove some of the distractions that platform suffers from. In addition, by giving players the opportunity to focus on the game, you are also meeting the need that the experts identified—that is, the players entering an altered state of mind that allows them to escape from their normal world activities and thoughts and become less self-absorbed. You are connecting with their need for excitement and removal from their current existence.

• Fun—All the elements I have previously described have emphasized the need for fun; in fact, Lazzaro defines all the elements of game play in terms of fun. I would also add that fun should be the goal of the game in social location marketing. A reward of some kind at the end of the game is a great bonus, but early experience shows us that many players do not actually collect their rewards, especially if the reward has a low financial value. Instead, they play for the sake of playing, simply for the opportunity to have fun and share that fun with others.

• Progress—Players need to feel that they are moving toward a goal, the reward, the end of the level, or even the end of the game. They need to know how they are progressing both overall and against other players. Whether this is the use of a progress bar, a leader board, a league table, or some other device, players want to see that their efforts are in fact leading to them being credited for that effort.

The Execution

All this theory is great, and no doubt you have followed intently along with every element discussed here and are now at the point of saying to yourself, “Okay, but what the heck does a game like this actually look like? Our company makes widgets; we aren’t a games company, we don’t build things for spotty teens to play on their X-Boxes, we aren’t going to spend millions on trying to develop the next World of Warcraft or even the next exercise craze for the Wii.

That’s actually a good thing. You don’t want to be in the games industry, unless that is the industry you are in already. The point is that although the theory might seem to make all of this very complex and demand that you understand how complex multiplayer online games are designed and coded, none of that is actually true.

I recently attended a conference in Las Vegas, and at the Sony booth I encountered a game being used as a marketing device that meets everything I have discussed in this chapter so far. Now, given that this is Sony, the technology company behind the PlayStation, I am sure you are expecting me to describe an amazing 3D virtual world populated with fantastical characters with which I was able to interact and that I lost a day in this alternate universe, in some experience that mirrored James Cameron’s movie Avatar.

Instead, what I am going to describe to you is a game that involved plastic cups. Yes, just a collection of 30 plastic drinking cups, the kind you can find in the party aisle of any grocery store. Of these cups, 29 were blue in color, and 1 of them was red. The object of the game was to transfer all the blue cups so that the red cup moved from the bottom of the stack to the top of the stack.

The player had to keep both hands in contact with the cups at all times, and each cup had to be moved individually (see Figure 3.3). In addition, Sony required that you compete against a minimum of two other players when you took part, and your time was entered onto a score board to see how you measured up against all the other players who took part during the conference.

Figure 3.3. A set of plastic cups makes for a great game.

The prize was entry to a drawing for a video camera. So the immediate payoff for a player was nothing more than the ability to find out where you ranked against other conference attendees who played the game. This game had all the things we have described. It was fun, it took concentration, and in doing so made the players less self-absorbed as they focused on the task in hand. Players could immediately see what progress they were making because they were able to note the position of the red cup as it made its way up the column of blue cups. In addition, the timekeeper called out the amount of time they had used so far.

The game required a certain amount of manual dexterity, not so significant that it was impossible to master but significant enough that times varied greatly from player to player.

For example, when I played the game I managed it in a time of 1 minute and 6 seconds. The young lady in the picture beat everyone with a time of just 48 seconds! People lined up at the Sony booth to play this and other games that they had arranged, all of which were being played with the same set of plastic cups.

This is a great example of how a game can be all the things that a player expects and yet be surprisingly simple in its nature and very low cost to execute. There is no reason something like this couldn’t be replicated at a café, bar, restaurant, or a retail outlet utilizing the social location sharing app as the method of entry to the competition. Get the players to check in at your location first, and then they get to play the game.

In doing this, you have managed to not only get them to spread the word about your brand, location, and so on, but you have managed to extend the engagement beyond their phone and into the physical space that you are occupying. This works equally well for businesses without physical premises or locations that are not normally open to their customers (in the business-to-business arena, for example). I will discuss this in Chapter 8, but it is more than possible for these types of games to be played at public locations—why not at the local park, marina, landmark, and so on?

Hopefully, you have seen that although game theory is a fairly complex subject and we have only touched on it in this chapter, it is possible to incorporate these concepts into simple and executable games that your business can afford and that will generate positive word of mouth about you as well.