5. Industries Making It Work

Most industries can make use of social location marketing as an effective communications channel; certainly, none should dismiss it without first clearly exploring the idea. Some industries in particular have made an early start and have blazed a trail that others in similar or associated fields can follow.

It is important to note that for some industries social location marketing is a difficult option, and for some it is simply not an option. This is true of social media marketing in general. If the industry has a customer base that is unlikely to want to share their purchases, their considerations or their locations, trying to force the use of social technologies on them is unlikely to work.

For example, I think it unlikely that the bail bond industry is going to find much use for social location marketing as a communication tool; it might be hard to explain to your network just how you became the Mayor of Jonnies Quick Bail Bonds, unless there is a really funny story behind it. Even then, sharing it on an app that your employer or future employer can access is probably not the smartest of personal branding moves. Equally, I’m not sure I’d want to get a Facebook communication letting me know that they have good rates on bonds this week. It doesn’t fit with the medium, and it doesn’t fit with the nature of sharing information, which is at the core of social media.

It is that core that differentiates social media from other forms of marketing communication. It might seem strange to be pointing that out in Chapter 5 of a book, but I think it is always a good reminder. The end purpose of social media is not to simply push out a message through yet another channel, but to deliver a message in a way that is both compelling and shareable, and that the recipients will want to share with their network.

As we have already learned, this is true for social location sharing. The nature of any campaign conducted via social location sharing is that it will be both compelling and shareable and will have an inducement/reason for being shared.

Regardless of the industry or whether the organization has a physical location, the fastest spreading campaigns will be those that both provide compelling and shareable content, and easy ways to share that content. For example, Foursquare has a more competitive feel to it and is focused on the status of mayorships and obtaining badges. Mayorships and badges tend to appeal more to male users. Gowalla is more focused on the acquiring of digital objects and the posting of pictures, which appeals more to women. SCVNGR is very focused on game play and the completion of challenges, therefore appealing to younger users who typically become bored with games that provide no challenge and are quickly completed.

It is important to think about the target audience when selecting an app. For example, Victoria’s Secret might want to target the male customer base by building a campaign on Foursquare. There, becoming Mayor has additional rewards that increase his standing within the game and that provide him with something that is appealing to his female partner other than the usual lingerie that the man might purchase. Thereby he can increase his real-world standing. For example, through the use of the tips feature, Victoria’s Secret might easily provide male buyers with tips of what women really want provided by the Victoria’s Secrets models themselves. This type of interaction is likely to increase usage of Foursquare at Victoria’s Secret (also increasing appeal to women users who see their male partners using Foursquare in a way that benefits both of them).

Equally, a clothing store such as American Apparel, which typically caters to the younger customer, might use SCVNGR to set up challenges at their stores that encourage their target audience to snap pictures of themselves in the same outfits as the mannequins in the store, maybe even with the mannequins in the picture. The sense of silliness, challenge completion, and the uploading of pictures all fit with the existing lifestyle of American Apparel’s audience. The addition of social location sharing and game play enhances the experience for this particular portion of its customer base.

A little creativity goes a long way in social media, and especially so in social location marketing. Encouraging interaction beyond the check in is essential. Campaigns that focus only on the check in will be very short lived and are unlikely to reach the level of social sharing that would be a part of any real measure of success. If you treat your company’s physical location as a real-world extension of the game environment that the social location sharing apps provide virtually, the players are much more likely to reward you with the level of sharing that you are seeking.

The following sections discuss how different industries are putting social location marketing to work.

Fashion

Traditionally, the fashion industry was not known for embracing social media. In fact, the fashion industry was quite scornful of bringing customers closer to the fashion houses for fear of trade secrets or the details of new collections being leaked.

Wesley R. Card, CEO of the Jones Apparel Group was quoted as saying:

“Even though I know we need to embrace it as a corporation, I am a little apprehensive.”

This is not all that unusual. In fact, it is more common than not for the C-Suite to be nervous about social media. Given that fashion is a highly talked about subject, embracing social media was not something that the industry could avoid for long. Whether they liked it or not, bloggers, tweeters, and social media participants were talking about them. The advantage that the fashion industry has is that it is constantly reinventing itself (they call it seasons). So after they decided that social media might actually have a place in their world, it was quickly embraced.

Suddenly, bloggers were being invited to shows during fashion events; they were given front row seats and provided with Wi-Fi to enable them to write and post at the event. Given that previously this was the realm of print journalism—which is still struggling with social media—it was clear that the fashion industry had woken up to the reality that people want instant information.

What the fashion audience didn’t want anymore was a magazine that showed them the New York fashion week two months after the event. The social media savvy audience wanted the fashions from the catwalk, preferably as they happened but at least the same day as the show. Magazines couldn’t deliver that in their traditional formats. Social media could meet the need. For their part, the fashion houses recognized this as well and realized that social media was a good thing for their industry.

Facebook, Twitter, and other social media apps have now become a staple of the fashion industry’s communication method. Some of the best looking Facebook business pages belong to fashion brands. Diane Von Furstenburg, a long-time advocate of transparency in the fashion industry, is a power user of Twitter, regularly sharing updates with the almost 100,000 fashion forward followers that want the inside scoop on what is happening at DVF (see Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. The fashion industry is now a power player in social media.

The fashion industry has had several successes with social location marketing in recent months, ranging from big brand stores to individual label events. Fashion is not an industry that you might immediately associate with social media. This, however, would be a mistake. The team at Coach, for example, uses social media extremely well in its efforts to bring the brand closer to its customer base by posting pictures and videos from Coach events, which of course always feature their products.

Jean brand Levi’s also utilizes social media as a central part of its marketing communications. It hosts events during popular gatherings, such as South by South West, mixing offline and online word-of-mouth marketing to create buzz about their products and brand.

These brands can achieve success because they know their customer profile extremely well. Coach knows that they are an aspirational brand for many young women, so the pictures they post show women who are similar to its target audience. It is also likely that Coach’s target audience carries smart phones. If that is true, it’s not too much of a stretch to assume that they are engaged in social media via mobile applications, which would include social location sharing apps.

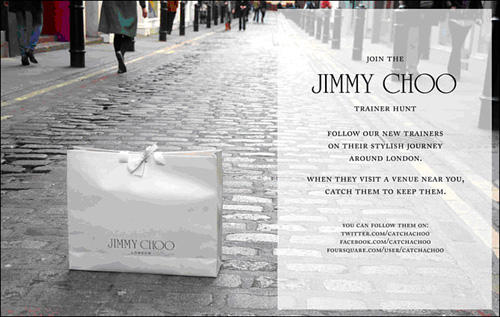

In April 2010, Jimmy Choo organized a treasure hunt in London called the “CatchaChoo” campaign (see Figure 5.2). The concept was that a Jimmy Choo representative would place a pair of Jimmy Choo sneakers at a location, snap a picture, post it to the CatchaChoo Twitter account, and finally check in with Foursquare to share the location of the sneakers. The person who found both the sneakers and the Jimmy Choo representative, and approached that representative with the phrase “I’ve been following you,” won a pair of the sneakers.

Figure 5.2. Jimmy Choo, I’ve been following you...

Although it was a simple concept, it played to the users’ sense of fun, gaming, and achievement. Best of all, it rewarded them with something of high value (for the non-fashion conscious, a pair of Jimmy Choo sneakers retails for around $500) that was worth putting in the effort to follow both the Twitter and Foursquare accounts of the brand.

By including the element of the verbal confirmation as well as the location tracking, Jimmy Choo’s was able to counter the issues of GPS unreliability and the system being gamed, which are especially important considerations when you are handing out high-value prizes.

By adding in this safeguard it provided the brand with the opportunity to ensure the campaign worked properly and provided them with photo opportunities that could be shared on other social media outlets, such the brand’s Facebook page, which encouraged others to take part in the campaign. After all, it’s one thing to hear about an offer, but quite another to see people actually win. By melding several social media sites into one campaign, the brand was able to bring to play each of the site’s strongest attractions for the users.

During the New York Fashion week, Fashion house Marc Jacobs partnered with Foursquare to create the “Fashion Victim” badge. The badge was awarded to those attending Fashion Week who checked in at any Marc by Marc Jacobs stores in New York and elsewhere in the United States. The reward was extended by randomly selecting four people who had unlocked the badge in New York to receive tickets to the Marc Jacobs show. See Figure 5.3.

Figure 5.3. If you were lucky enough to unlock the badge in New York, you were awarded a Fashion Victim badge.

These types of partnerships recognize the needs of the customer to feel recognized by their favorite brands, to be rewarded for their ongoing loyalty, and to feel that they are a part of a brand community that receives “insider” information that other casual customers are not getting. Campaigns that have two reward levels—one that is an intrinsic part of the app and one that is part of the real world—have a strong appeal to users of social location sharing tools. Status, badges, and recognition within the community of users is a motivator, but the addition of something more tangible to a campaign has a much higher chance of being talked about, shared, and commented on than simply the awarding of a badge within the game.

This is a valuable lesson for marketers to bear in mind when thinking through the construction of social location marketing campaigns. There must be a real-world element for maximum effect. Users will not talk about your campaign if their only rewards are points, badges, status upgrades, or other game objects. For them to share with their network in a personal way, the reward has to be something that evokes a response at the personal level, preferably an emotion such as excitement.

Retail

Retail is an area in which you might expect to see social location marketing being leveraged early and often. Retailers—especially those with brick and mortar stores—are acutely aware of the need to provide their visitors with a great experience to ensure that their visitors become customers. More important, retailers want those visitors turned customers to become repeat customers.

The retail market has long explored reward programs. One of the earliest was the very simple clip card type that was marked, stamped, or punched each time a customer made a purchase. Eventually, these became electronic cards that are tied to point-of-sale systems and direct mail campaigns that include offers, specials, and discount coupons.

The advent of online retailing did not see a decline in this type of reward program. Shoppers still want to be rewarded and engaged, even if they are not interacting directly with a store representative. Understanding this behavior pattern of “I will buy something from you, but what’s in it for me?” is key to understanding why rewards programs are key to the progress of social location marketing campaigns. Although some retailers might view this as almost a sense of entitlement on the part of the shopper, it can become a differentiator in the way a consumer makes a purchasing decision.

The key is to make the rewards attainable, have a tangible benefit to the consumer, and not be something that can either be cheated or acquired in a way that doesn’t also benefit the retailer. Although this sounds ridiculously straightforward, too often retailers fail to recognize these basics and make the rewards worthless to the consumer because they are too generic or so valuable that it is almost impossible to offer the reward to the majority of customers. Neither situation is ideal.

Given the amount of customer data that most loyalty systems are capable of capturing, rewards that are generic are almost inexcusable. Although it is impossible to do individual print runs when sending thousands of discount coupons out to customers, it is feasible to group them.

For example, sending a discount voucher to a children’s electronics store customer when that customer’s buying pattern and visits to the store shows no indication of buying that type of product is counterproductive. Not only is it going to land in the trash can quickly, but it might leave the customer wondering why the voucher was sent or why he or she wasted time opening it. This leads to a decline in open rates of future communications, whether electronic or direct mail. Therefore, the closer to personalized experiences retailers get, whether online or offline, the better.

For example, a chain of electronics goods stores will be divided into different departments, such as computers, telecommunications, home theater, appliances, and so on. By learning the customer’s buying behavior, it is possible to group coupons and offers by customer persona. Those who have bought computers and accessories might be interested in offers for additional computer accessories and possibly home theater. Those same customers are less likely to want to receive offers about children’s bicycles.

However, cross-sell and up-sell opportunities can’t and shouldn’t be ignored. Just because a customer has never bought an appliance, it doesn’t mean they aren’t in the market for one. If you miss the opportunity to let them know you have an offer for them, you are leaving money on the table—money that your competitors will happily collect. However, most of the offers I receive seem to have no relevance to me whatsoever and don’t relate to purchases I have made with a particular retailer.

So what relevance does this have to social location marketing? Social location marketing is the perfect means for learning what each customer is interested in purchasing and then marketing directly to that customer. Campaigns that are untethered from appropriate customer data—as is the case in the majority of social location marketing campaigns—are much harder to make relevant. However, with a little thought and creativity, retailers can create compelling campaigns that provide the right level of relevance and incentive.

Creating relevant campaigns that incentivize your customers can range from seasonal offers/rewards that tie into existing in-store promos to category-specific rewards based on store performance. Although most businesses enter their venues in social location sharing apps as a single location, if they have multi-departments they could enter each of the departments separately. For example, electronics, appliances, music, phones, and home theater could all be sublocations of the main location, such as “Electronics@Joe’s Gadgets.” Customers could then check in specifically where they are shopping within the store.

Rewards and offers can be segmented across the store by department, which allows relevance to be built in. Using segmented offers also allows you to tie rewards to in-store promotions—especially those offered by third-party suppliers. Tying rewards to in-store promotions can be a powerful marketing tool that is both low cost and can be leveraged through a social location marketing campaign. Setting up rewards and incentives such as those discussed here isn’t difficult. Doing so simply requires a little thought about what would appeal most to your customers and what is likely to be most successful.

Partnering with a specific social location sharing tool, such as Gowalla, can also lead to a more integrated and rewarding experience for the end user. Partnering also allows the retailer to offer more compelling ways to involve its customers, which leads to more sales. For example, why simply have a generic pin for your chain of stores? Why not partner with Gowalla to have a custom one created (such as the custom Levis pin shown in Figure 5.4)? You could create something that stands out on the customer’s profile page and attracts the attention of his or her network. This is a simple, low cost, and effective method of branding within Gowalla.

Figure 5.4. Creating a custom pin is a low cost branding method within Gowalla.

Build a reward around the earning of the pin, or better yet create a tour within the store so that the customer checks in at various departments and is therefore exposed to all your in-store merchandizing, and then claims her reward. In a space that small, it is easier for users to game the system by simply standing in one place and checking in at all the locations created within the store, so giving away a 50” flat screen TV to everyone who completes it is probably not a good idea. However, giving away something small or something that is an inducement to further purchases would be worthwhile.

Another idea is to use SCVNGR to set up a treasure hunt through the store, inviting people to interact with, rate, and snap pictures of themselves at various locations. For example, Best Buy is currently running a lot of promotions of their new line of electric bikes. Why not host a challenge in store that perhaps involves trying out the latest 3D TVs, followed by a computer department experience that leads to the audio department and ends in a test drive of an electric bike? This becomes a simple way of driving traffic through an in-store set pattern, which is something that traffic flow analysts in larger stores already try to establish. Social location sharing tools can be leveraged to achieve the same effect that previously required changing the entire layout of the store to direct traffic in a specific pattern.

Customer expectations are rising constantly with the release of new technology. Customers are looking for the environment around them to integrate ever more with their technology adoptions. It is no longer enough for a store to post a window cling or put a sign by the checkout that reminds users to check in at their location. This only leads to check-in fatigue. Rather, retailers and other marketers using social location marketing must look at ways in which they can provide an interactive experience in-store that leverages the technology in the pocket of their visitors—an experience that will convert them from browsers to buyers and from one-time customers to loyal fans who act as advocates in both the real and virtual worlds.

Integration is fast becoming a key to extending the social location sharing applications (see the Tasti D-Lite case study at the end of this chapter for a good example). Some social location sharing apps are being rolled out that serve no purpose other than to integrate with loyalty programs and to make it easier for both consumer and store to use the systems. Rather than emphasize the social networking or gaming aspects of the previous generation of apps, these apps exist solely to make interacting with social location sharing programs easier.

One such app is Shopkick (www.shopkick.com). Shopkick is currently being rolled out on a trial basis by stores such as Best Buy, American Eagle, Sports Authority, and Macy’s. At the time of this writing, it was available only for the iPhone. Shopkick is an app that the customer runs prior to entering the store. After the customer enters a store, in-store technology picks up the presence of the user’s app and registers the user at the store. This is not a social location sharing application in the way we currently understand them, because it does not rely on GPS. Rather, Shopkick is a hardware/software combination. Instead of relying on the phone’s GPS, the in-store hardware seeks a signal from the app running on the phone. The signal tells the in-store hardware that a user running Shopkick is nearby, allowing a connection to be made. It is, however, a potential direction that social location sharing might go in, and it is interesting to see it being explored by retailers first.

This concept of moving away from the manual check-in service and to an automated service that requires only that the customer be running an application has a lot of potential. The customer is “pushed” relevant coupons and offers that are usable in the store when they are there or on future visits. This technology is even more emergent than the others in the social location sharing space (it launched early September 2010), but it will definitely be interesting to see both the customer and merchant adoption rate for this. Certainly it requires less effort by both the customers and the stores, which is always a good indicator of adoption.

The concept requires less training for the store, and because the customers do nothing other than install and run an application, they don’t forget to check in; therefore, they don’t miss out on reward opportunities. The retail space, in particular, is especially attractive for Shopkick. In what is already a fiercely competitive space, additional costs for training on social location marketing tools are hard to justify. Although it is very early in the adoption cycle to show real numbers, this type of engagement can only increase conversion (from browser to buyer) in the longer term, especially if the offers that are pushed are kept relevant and useful.

Given the amount of innovation, it will be interesting to watch the retail industry closely for ideas on how to leverage social location marketing for all other markets. This is true because many ideas that are born in retail transfer readily to other customer-focused segments.

Food and Beverages

This was one of the first areas to embrace the concept of social location marketing. Indeed, the earliest rewards offered by venues on Foursquare were the now ubiquitous free cup of coffee for the Mayor (see Figure 5.5).

Figure 5.5. Mayors get a free cup o’ Joe.

Since then, the concept has grown in popularity across the board with these types of venues, venues are becoming more adventurous in their use of social location sharing apps and the way in which they offer rewards (see AJ Bombers case study in Chapter 6).

This desire to become more adventurous is a great benefit for the users. When marketers either choose (or are forced) to be more creative, the result is often an increased benefit to consumers. Certainly, marketers are being constantly challenged to improve their offerings, if only from a creative perspective when it comes to social media marketing and in particular with social location marketing.

Some critics of social location sharing have observed what they refer to as “check-in fatigue” and that users, having been avid members of the social location sharing community, become jaded with the process of checking in at every venue they visit.

Part of that fatigue is caused by the lack of incentive to participate in social location marketing. If marketers want consumers to use apps such as Foursquare and Gowalla so that they can market to them, it’s up to the marketers to give consumers a reason to do so. The days of a free cup of coffee have passed. With the increasing sophistication of the apps, coming up with compelling reasons for consumers to allow themselves to be marketed to will become easier. For example, the savvy marketer can use SCVNGR (see Chapter 6 for more details) to get beyond the check in and encourage the visitor to become engaged with the venue in a way that a simple check in does not allow.

However, this level of creativity is not restricted to SCVNGR. All the social location apps offer opportunities to take the engagement beyond the check in if the marketer has a good vision of who their target audience is and how they are currently using the app. This is why I think it is essential for any marketers who want to seriously fold social location marketing into their social media marketing plan to be actively involved in social location sharing and to use as many of the applications as possible. Only then can you truly understand which apps best fit your particular customer profile and create campaigns that best meet the needs of those customers.

Beyond the usual suspects that form the top tier of social location sharing tools (Foursquare and Gowalla, for example) are the tools that integrate with more than one service and then offer marketers (particularly in the retail space) the opportunity to build reward programs of their own design on top of the location data.

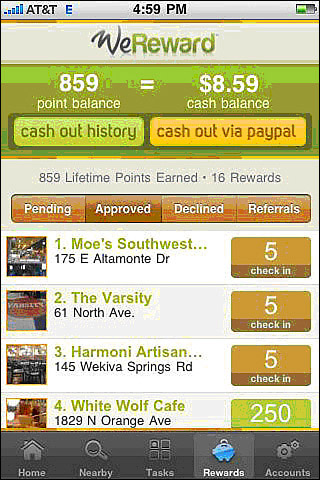

One such service is WeReward, which offers a cash-based incentive program for marketers to leverage (see Figure 5.6). WeReward is integrated with Facebook, Twitter, Yelp, Google, CitySearch, and Foursquare and is available on iPhone, Android, and Blackberry operating systems. WeReward provides users with the capability to check in using their usual apps and participate in reward programs that can lead to cash rewards.

Figure 5.6. WeReward is a cash-based incentive-based app for iPhone, Android, and BlackBerry.

For example, both Domino’s Pizza and Jones Soda Company operated programs using WeReward in which customers were tasked with checking in and uploading a photo of their purchases. For Domino’s, it was a picture of the pizza box, including their receipts; for Jones customers, it was pictures of the bottles that had been purchased.

By requiring customers to upload pictures, the brands were able to verify the purchase and then offer a monetary reward per point earned. The brand sets the value of the points and controls the budget of each campaign. WeReward only charges the brand (such as Domino’s) for those customers who actually take action (such as taking a picture of a pizza box), so the brand is paying on a per action basis, not on a per view, per click, or other model that is so common in online or mobile advertising.

In effect, if the campaign does not drive actual customers, then the brand pays nothing because there are no setup costs or minimum commitments. This makes for a very compelling case to use this type of service. While similar in nature to SCVNGR, the added level of financial rewards makes this a service that should strongly be considered by marketers with the intent of actually engaging their customers beyond the check in. In my opinion, this service is a must for all campaigns of the future in social location marketing.

McDonald’s tried Foursquare as part of the national (in the U.S.) “Foursquare Day” on April 16 (4/16 is four squared). They offered a total of 100 gift cards valued at either $5 or $10 to Foursquare users who checked in at their venues on that day. The external sell was not the only obstacle to this campaign. Internally, many members of the marketing team had never heard of social location sharing and Foursquare. So, as with many social media campaigns, there was an element of internal education and convincing before the campaign could be launched.

By selecting a day that was already receiving media attention, McDonald’s was able to piggyback on the attention and increase the publicity for its own campaign. This is where the creative thinking part comes in. Don’t just think about your own campaign, but think about how that fits with broader campaigns that are capturing the media and the attention of your potential customers. McDonald’s saw an increase in the number of visitors to its restaurants, which rose by 33% on that one day. They also saw a much broader raising of social media awareness—some 600,000 social media users choosing to follow, fan, or otherwise engage with the brand on other social media sites. Also, McDonalds garnered more than 50 articles in the traditional press covering its campaign. A regular campaign would struggle to receive one tenth of that coverage.

For a one-day campaign, those results are hard to beat. Traditional media would be extremely costly to even attempt to replicate that type of result. Although they don’t disclose the sales effect, with a 33% increase in foot traffic through the doors, one can safely assume that McDonald’s saw a corresponding increase in sales.

What is really interesting here is the cost of the investment for McDonald’s—a company that spends millions of dollars every year on advertising and marketing. The total cost of this campaign was $1,000. Yes, you read that correctly: $1,000. This type of success is very achievable for marketers using social location marketing provided that you use it in ways that appeal to the user base. The gift cards as rewards appealed to McDonald’s customer base because they are likely to be repeat customers. So by visiting the store and checking in, customers had the opportunity to win what was, in effect, a free meal. This was a simple inducement, but because McDonald’s knows its customers, it was an effective one.

It is not just restaurants that are leveraging social location marketing campaigns. Domino’s pizza partnered with Foursquare in the UK to offer customers a free side dish valued at approximately $14 when they checked in. What is unusual about this is that Domino’s has no dine-in restaurants in the UK. They are take-out or delivery venues only. This means that customers checking in are not staying at the venue but ordering take-away food. This clearly illustrates that a venue, even in the food and beverage space, does not need to be limited to those that offer the “sense of community” that is associated with bars and restaurants that actively promote coming with friends.

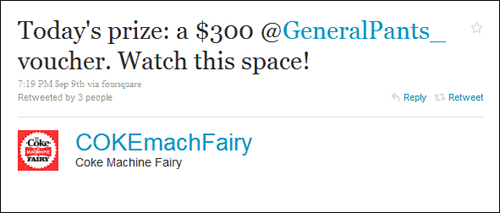

Similarly in Australia, Coca-Cola partnered with Foursquare to run the Coke Machine Fairy campaign. Coca-Cola did this by creating an account in the name of the Fairy on Foursquare. The fairy would then visit locations around Sydney, Australia, and leave a “magic” can (see Figure 5.7). The Fairy would then check in at the location of the can.

Figure 5.7. Coke drinkers in Australia were rewarded for finding the “magic” can.

Foursquare users who had become “friends” with the Coke Machine Fairy would then be able to see where the latest check in was and know where to look for the “magic” can. The first person to actually find the can was then rewarded with a real-world prize—something along the lines of a gift certificate to a clothing store, for example. Although this type of campaign has been run before and on other apps (Gowalla, for example, used this type of promotion to launch its own app), what makes this stand out is that Coca-Cola has no physical retail locations of its own.

There isn’t a store that you can go to that is specific to the brand. Even the vending machines are owned and operated by other companies. So for Coca-Cola to leverage social location marketing, it had to co-opt other locations to promote Coca-Cola.

By offering prizes that weren’t specifically connected to Coca-Cola, it provided a fun element—tracking down the Fairy—and perceived value to the customer/user. Prizes weren’t just more Coke (which the person had already purchased), but clothing and other items.

The Coca Cola example proves that companies that might have thought there were no social location marketing opportunities available to them need to think again. Finding something that will induce people to come to your venue has always been the challenge for any food and beverage outlet. Social location marketing doesn’t solve that issue. However, what it does do is provide you with a low cost/no cost channel to promote the offering. Understanding this distinction is the key to understanding how to use social location marketing.

You will no doubt have noticed in this chapter that I continue to press home the need to know your customers. The use of social location marketing only reinforces that need. Thinking through the offerings that are likely to be most appealing to your audience and then those that will appeal to the users of this type of technology is key to having an effective campaign.

When designing your first campaign, you should review what’s already been successful for your company and then marry that with social location marketing. Obviously this is not the first time Domino’s has offered free food as an inducement to get potential and repeat customers to come to their venues and place orders. However, adding the requirement that the customer has to check in on Foursquare not only limits the uptake of the offer but provides Domino’s with a unique snapshot of its customer base. They now have an idea of how many are early adopters/smart phone users who like to share socially.

Gathering this data helps them build future campaigns that are slanted specifically toward this audience. This trial and adapt methodology is frequently used when implementing social location marketing strategies. Because the entry cost is low when it comes to social location marketing, organizations large and small can afford this approach. In contrast, using a trial and adapt approach with traditional forms of marketing would be cost prohibitive because errors or missteps can be costly—both in terms of brand reputation and financially.

Hotels and Travel

Perhaps more than any other industry, the hotel and travel industry understands the value of good customer service. They understand that word of mouth can be both a blessing and a disaster, depending on the experience the customer chooses to spread. They also know that customers are much more likely to talk about a bad experience than they are about a good one.

Intercontinental Hotels partnered with Gowalla as a method of leveraging social location sharing as part of its marketing communications. When guests checked in at either the Holiday Inn or Crowne Plaza, they received targeted promotional information through Gowalla about Intercontinental’s “Hit it Big” rewards campaign through which guests could receive either double points or up to $500 in gift cards during the summer months. The point of using Gowalla is that Intercontinental knew that the customer was actually on property when they received the promotion and were therefore more likely to respond to the call to action than if the customer received the information through a more traditional means, such as via email.

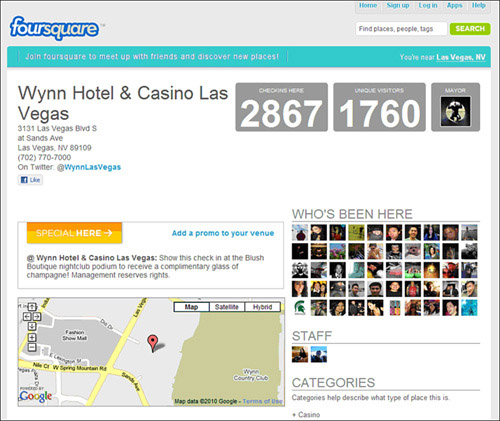

Similarly the Wynn Hotel in Las Vegas claimed its venue on Foursquare and set up a special for users. Having completed this process, the hotel was rewarded by guests who not only checked in but left valuable tips for other guests. These tips included such information as which rooms have the best views, drink recommendations, restaurant recommendations and more (see Figure 5.8).

Figure 5.8. Wynn Hotel in Las Vegas offers specials to customers on Foursquare; customers, in turn, offer valuable tips for other guests.

This type of user-generated content adds to the experience of the user checking in at a location and is especially important for the hotel industry. Although a guest might well have read a review or two before arriving, being given tips by other guests as they check in on Foursquare or another app is quite another matter. These onsite tips immediately remind customers that they are part of a community experience and prompts them to leave their own advice and tips for other guests. This sharing of information occurs without the hotel having to expend resources creating the content.

Hotels continue to put out feedback forms in their rooms, but those forms go largely ignored until a guest has a bad experience. With the advent of customer ratings on booking sites such as Expedia, Hotels.com, and others, guests are free to share their feedback at anytime, whether it is good or bad. Many of these systems—because they are independently run—show both the good and the bad and sometimes the downright scathing.

The hotels on the receiving end of these reviews have no opportunity to edit the comments before they are seen by the buying public, which adds validity and credibility to the site, but does little for the hotel being reviewed. If your hotel business gets enough bad ratings, you could find yourself with a PR nightmare on the very websites from which you are hoping to have bookings made.

Given that the hotel lobby and the reception desk are the first point of contact in the real world for a guest, a bad impression here is very likely to be shared with the guest’s network before the hotel staff even get the opportunity to offer an explanation or greet the guest. Travel is, by its very nature, a tiring and sometimes trying process. Travelers often arrive at their destinations in a less-than-optimum frame of mind. They are looking for a painless and swift experience at a minimum. The more they have paid, the more they are looking for in terms of a frictionless experience.

It is often the minor friction points that at the moment of occurrence seem to create so much annoyance that they are shared with a user’s network. I recently saw a tweet that described the check-in line for a car rental service at an airport in the following way:

“I swear I have given birth to children in less time than it is taking to get a car.”

Not the best recommendation for a car rental service by a customer who had just gotten off a plane, written and shared with a large network before the company representative could even greet the user. This is the power of a smart phone and the simple act of adding a comment to a location check in.

This type of comment is not only viewable at the time it is written; it is now permanently attached to the location. Other potential customers, arriving from flights and about to check in at the airport, can view this comment. Are they likely to choose this service, with this type of comment?

In all likelihood, the customer service representative never saw that comment; most organizations do not use these services as methods of feedback or to follow up with customers who have a bad experience—at least not yet. These services are poised to replace the comment card, the customer survey, and the myriad other methods that have been deployed by organizations to garner customer feedback in the past.

Why go through the process of designing expensive surveys when you can simply review the comments that your customers are leaving when they check in?

Why not build a reward system around the check-in process that asks customers to not only check in but rate the experience at the same time? This would provide a company the reassurance that the feedback was relevant to the experience since the feedback was given at the time of action.

By making the customer participation in the feedback process as painless as possible and by reducing the disruptive nature of the feedback process, the customer is more likely to participate. Given that the feedback is likely to be given during the stay, the hotel or destination also has an increased opportunity to rectify any issues, perhaps even turning the situation from a loss into a win.

These positive situations are often followed by an equal amount of social sharing because people rarely like to be the sharers of only bad news. Everyone likes a story with a happy ending, and when an organization shows that it is responsive to the bad experiences of its guests and takes steps to put things right, people share those stories, too. Often the expectation is not that the organization won’t make mistakes but that they will own the mistake and make amends as swiftly as possible.

Had the car rental company I mentioned earlier in this section been using the same social location sharing app that the comment was left on, they could have reached out to the customer and offered to make amends—a free upgrade or something that might equal a happier customer experience.

Some hotel chains and travel companies are already adopting social location sharing tools to tie in with their preexisting customer loyalty programs. Utilizing services, such as Top Guest, that offer the ability to integrate social location sharing check ins with a hotel chain guest loyalty program makes it easier for the customer to earn rewards and easier for the hotel chain to promote its locations.

The premise is very simple. When guests check in at a hotel, they are either encouraged to utilize a social location sharing tool, such as Foursquare, Gowalla, or Yelp, to share their locations, or they are automatically checked in by producing their loyalty cards.

Either way, the check in is shared to their networks. This immediately provides the location with credibility among the users’ network. Why? Because for the most part, what we think of as word–of-mouth marketing is really referral business. Referral business is something that the hotel and travel industry has long been acutely aware of as a driver of business.

If I am looking for a hotel in a specific location or even just a particular brand of hotel, I am more likely to pay attention to a requested or even unsolicited recommendation from my network then I am to pay attention to a branded marketing message via traditional mediums.

By unsolicited, I refer to the stream of sharing via status updates to which the users of social media are constantly exposed, such as Facebook posts, Twitter updates, LinkedIn updates, and Tripit plans. All of these form the backbone of the social media connected individual.

Still, timing is everything and timing will not always prove to be serendipitous for the brand. The network has to be large enough that the status update has the potential to reach others who are in the process of considering airlines or hotels for their travel plans.

However, given the large volume of customers all sharing their locations with their networks, gathering and using this data becomes an area of increasing returns. Brands are starting to leverage an increasing amount of social data as part of their customer relationship management process and are identifying customers who have networks of sufficient size that they can actually affect the brand’s efforts. Influence is the new black. Just as a maitre d’ will still snap to attention when presented with a black American Express card, soon brands will find ways of identifying their most influential customers and treat and reward them accordingly.

Social currency has the potential to become as much a factor in how a brand does business with a customer as the credit score is today. A user’s ability to gather a large following and, by virtue of his or her perceived social media status, wield purchasing influence on that following is already a valuable asset. Following on the coattails of social media, these influencers will become primary targets of marketing campaigns. Brands that are investing in how to identify influence and what exactly that influence means to them will be best placed to leverage this change. As social media and social location marketing gain ground and acceptance by both users and brands, brands that have built these key influencers into their marketing campaigns will be well ahead of the curve.

As you can see from these examples, integration is definitely the path that social location is taking for the hotel and travel industry (if not all others). This involves investment beyond the normal marketing campaign and starts to involve IT and infrastructure changes that affect the business as a whole—certainly at the enterprise level of adoption. For the smaller business, integration comes at a lower cost and at a lower technology point, but at a higher resource cost in the form of staff training and so on.

If you read the case study of the Capital Hotel at the end of Chapter 2, you will see how they tackled the integration issue by training their staff on how to utilize social location sharing tools and how to pass that information on to customers. This illustrates how smaller hotels can still compete with the larger players in their space, even when the larger players can afford to provide technology solutions by integrating the tools into how they do business.

Integration doesn’t always mean expensive technology solutions. Integration can—and often should—be more about how these services become a part of the normal method of doing business.

By encouraging staff members to become advocates of the new business methodologies outside of work, a business becomes its own word of mouth hub and activates customer interest in what it is doing that is different. Differentiation, not just at the product or service level but at the delivery point, is something that attracts attention and encourages customer exploration.

Think back to the McDonald’s example earlier in this chapter. This offer didn’t draw lots of people to its restaurants simply for a chance to win a $5 gift card. People came to the restaurants because McDonald’s was embracing something that very few people had actually heard of—Foursquare Day. This implied that McDonalds was plugged into the cutting edge of popular culture and that by association, its customers could also be a part of that experience. In other words, it wasn’t something that they perhaps had previously associated with buying a Happy Meal. By exposing its customers to Foursquare, McDonald’s was creating an audience for future campaigns. People new to Foursquare learned how to use it and joined existing Foursquare users as an audience for future social location marketing campaigns. This is a very important consideration when determining how your existing customers and potential customer use the technology.

If you believe your customers or potential customers are not early adopters, as AJ Bombers did at a local level and McDonald’s did at a national level, provide an experience that introduces the technology to them and encourages them to use it. Become the source of information, not just rewards. The marketing process can be both educational and informative, as well as a vehicle to drive sales. By providing customers and potential customers with an insight into the future, they have another reason to regard your brand as an object of loyalty.

Think of the way Apple markets its products. Much of the loyalty is driven by the fact that Apple customers believe they are on the inside track of new technology. You don’t have to be a technology company to achieve the same cachet. Simply partnering with the right technology as part of your marketing can do that.

Summary

After studying how social location marketing can be used in various industries, several common themes should have emerged. First, it’s important to know your audience, which is important with any form of marketing. Second, it’s important that you understand how your customers use social location apps, such as Foursquare and Gowalla, so that you can tailor your marketing efforts accordingly. Last, and perhaps most important, you need to add some imagination to the mix.

Assuming that you have determined that social media marketing in general and social location marketing in particular is a good match for your customers, keeping these three basics in mind will go a long way toward ensuring that your campaigns are successful. What cannot be overstated is that with social location marketing, it’s okay to try something and adjust as necessary on-the-fly. Given the low cost of entry for most social location marketing campaigns, you can use a trial and adapt approach that would be cost prohibitive in other forms of marketing.

In addition, keeping a careful eye on how social location sharing is evolving is very important. The examples given in this chapter revolve mainly around Foursquare and Gowalla because, as the early leaders in the field, they are currently the ones with the most compelling case studies. However, as discussed in Chapter 4, they are not the only apps available. Other apps are being designed to compete with Foursquare and Gowalla, while still others are being designed to put an entirely new spin on social location sharing. You also shouldn’t ignore Facebook and Facebook Places. While Facebook Places has yet to prove itself commercially useful (at the time of this writing, anyway), it is only a matter of time before it starts to produce results. I would expect to see case studies starting to appear from companies that have already found ways to leverage Places as it currently exists.

You might remember that Foursquare started out as a game. Before Foursquare offered business metrics and the plethora of other partnerships, businesses found ways to incorporate it into their marketing mixes, so you can be sure that businesses are already finding ways to incorporate Facebook Places into their marketing mixes, too. As the existing apps recognize the need to move beyond the check in, watch for new feature sets. I think we’ll see features added that allow for better integration with existing corporate infrastructures. I also think we’ll see features such as those found in WeReward that allow smaller organizations to create compelling reward programs around their customer loyalty programs.

Today, there are services available that will construct marketing programs using social location sharing apps in a method that requires very little involvement from the marketer.

The appearance of these services is not necessarily an indication of the stability of social location sharing. However, their existence does imply that a significant number of companies are investing in the concept and that means it is here to stay. This in turn means that more organizations and more verticals will start to incorporate it in their marketing mixes. Just as micro-blogging started with numerous apps that gradually mutated into the market leader, Twitter, so it is likely that the social location space will devolve. However, where I see a big difference in social location sharing is that there is unlikely to be a one-size-fits-all solution that works for all verticals. That means we will see more diversity remain in this space than we saw in previous shake ups of the social media tool set.

Facebook, while bringing with it the largest audience of any single social media app, is still not the right place for every business to carry out its social media communications. The same holds true with Foursquare, Gowalla, Yelp, and any of the other social location sharing options currently available. I strongly believe we are at least another year from seeing the rising curve of innovation in this space start to plateau to such an extent that it will become obvious which app best fits which vertical. Even the apps themselves have shifted focus over the past six months. For a while it seemed that Gowalla was going to focus almost exclusively on the travel industry, which seemed a logical choice given its “Trips” feature. Gowalla pursued and secured partnerships with the Travel Channel and National Geographic. However, in recent months, that seems to have been downplayed as Gowalla pursued other industries and broadened its offerings.

What is certain is that every app is starting to include metrics capabilities, which is something that the more established apps already offer and is demanded by business users. For example, Yelp has had a business dashboard for quite a while. Foursquare now offers some business metrics. Gowalla and SCVNGR promise these are in the near future. If the rest of the apps are to continue to secure partnerships and be taken seriously by businesses, they will have to incorporate these metrics. Marketers demand these metrics capabilities so that they can provide the kind of performance feedback the C-Suite requires. When these metrics capabilities are not available, an app can quickly fall out of favor with business users.

Andrew Koven, who leads e-commerce for Steve Madden, has been critical of the experience his brand has had with these services. He said results from its partnerships with Foursquare and Loopt haven’t been very compelling to date, and he didn’t see much reason why Steven Madden would sign up with Shopkick.

Although part of that negativity can be attributed to setting unreasonable expectations for an emerging service, it also has a lot to do with being able to provide accurate resultsets to partners. If these apps are to meet their true potential—and I truly believe that they have the potential to affect the way brands of all sizes do business in the future—then the apps themselves have to start to develop more robust reporting systems. These reporting systems must be able to clearly show those compelling results for their users and allow for more streamlined communications between the brands and their customers and potential customers.

Brands want to be a part of the community. Simply knowing that they had X number of visitors check in at one of their locations on a given day won’t cut it in the longer term. They want to and need to be able to reach out to those visitors. They want be able to tie those visits to sales or abandoned carts in much the same way as the detailed metrics provided by online shopping allows them to see customer behavior.

Ultimately, social location sharing tools—at least from a marketer perspective—should allow behavior to be modeled in the same way as web store analytics do for the online shopper. Where did the customer come from? Which competitors have they visited? What did they view in my store? What did they purchase? Where did they go after they left the store? Of course this will sound like a privacy nightmare to most people outside of the marketing sphere and even to some within it. However, given that this type of data is readily available to the online marketer, the expectation that social location marketing will marry online/mobile marketing to the real world, it is not unreasonable to think that marketers will want to match as closely as possible the type of data that they capture in the purely online world.

Case Study: Integration and the Seamless Check In

Venue: Tasti D-Lite, East Coast United States

Participant: B.J. Emerson

Background:

Tasti D-Lite is a chain of ice cream stores originally founded in New York in 1987 and now headquartered in Tennessee. They made the decision to enter the social media realm and were experimenting with Twitter and Facebook. In doing so, they caught the attention of their point-of-sale supplier, PC America, who had been experimenting with the Twitter and Facebook APIs.

PC America offered to integrate the Tasti D-Lite social media effort into their POS system, and after some brainstorming it was decided that Foursquare would also be integrated into the system.

Tasti D-Lite wanted to provide a process for their customers that was as seamless as possible, that encouraged adoption, and that increased customer data. In the end, their concept was surprisingly simple, at least from the outside.

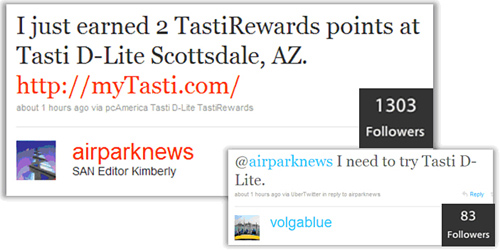

They would integrate their social media efforts with their customer loyalty program, allowing customers to update their Twitter status, post to Facebook, and check in on Foursquare at the same time by using their Tasti-Treat Card. Further, they would allow the customer to preselect the messages that the system sent out for them or create their own. If no messages are selected or created, a default message would be sent.

For example:

“I just earned 5 TastiRewards points at Tasti D-Lite Columbus Circle, NYC! http://myTasti.com.”

A simple enough message, but one that contains both the brand name and an inducement to the customer’s network to also use the service—after all, who doesn’t want rewards? The customers are given an additional 1 point for each social network that they connect their account to for each purchase that they make. Adding Facebook, Twitter, and Foursquare gives them three additional points for every purchase, which accelerates the point at which they receive free items in store.

In addition to earning points, customers also receive updates on when their favorite flavors are back in store. This is a great way for Tasti D-Lite to promo limited time flavors, such as Pumpkin during Halloween.

Tasti D-Lite had some very good results with this program. More than 27% of the customers who had a loyalty card opted to connect it to their social networks (see Figure 5.9). The average number of connections each customer had was 91.

Figure 5.9. Tasti D-Lite saw nearly 30% of its customers who had a loyalty card connect it to their social networks.

As Figure 5.8 shows, a predefined tweet can still elicit responses from a customer’s network. Multiply that by the number of customers that were willing to connect their loyalty card to their social network accounts and you have more than enough content to drive real sales.

Part of this success is undoubtedly the fact that Tasti D-Lite, by opting to integrate their social media campaign with their loyalty program, made it frictionless for their customers to take part. If the customer has no additional steps to take, then why would they not want to take part?