19

Social Control

Learning objectives

- Introduction

- Meaning of social control

- Purposes of social control

- Essentials of social control

- Development of the concept of social control

- Need for social control

- Types of social control

- Application of social control theory

- Customs

- Tradition

- Folkways

- Norms

- Mores

- Law

- Education

- Deviance

- Influence of social control on health behaviours

1. INTRODUCTION

Man is a social animal. He lives in groups. Life in a group requires that each member must recognize his duties and obligations to his fellowmen and to his society. Every society has harmony and order. Society, in order to exist and progress, should exercise certain control over its members. Any deviation from the established way is considered dangerous to the welfare of the society. Social control acts as an influence and may be through public opinion, compulsion, social suggestion, religion, and so on. This influence is exercised by a group, and the group may be family, church, state, school, and so on. The influence is exercised to promote the welfare of the group as a whole.

In other words, the society has to exercise control over its individual members, and sociologists refer to this as social control. Social control means the system of devices whereby society brings its members into conformity with the accepted norms of behaviour. For this, we must seek out the ways in which society patterns regulate individual behaviour, and at the same time, the ways in which society behaviours, in turn, serve to maintain the social organization. E.A. Ross considers public opinion as a powerful means of dissuading an individual from pursuing a completely selfish course of action. It plays an important role in compelling the individual to follow a course of action that the group considers as desirable.

2. MEANING OF SOCIAL CONTROL

Social control differs from self-control in that self-control is for the individual, whereas social control is for the group. Social control and socialization are interrelated. During socialization, social control will also be in operation. Social control is necessary to maintain the old order. Family helps in the realization of this objective. Social control is necessary to establish social unity. The family maintains its unity because its members follow the family norms. Social control is needed to regulate or control individual behaviour. If social control is not effective and every individual is left to himself, the society becomes a jungle. Social control provides social sanctions. If an individual violates social norms, he may be punished through sanctions.

E.C. Hayes distinguished between social control by sanctions and that by suggestion and imitation. Control by sanctions involves a system of rewards and punishment. This is the same as repressive social control. Hayes considers control by suggestion and imitation as more desirable. For instance, control of juvenile delinquency through proper training and education is certainly superior to repressing deviant behaviour by imposition of laws. According to Hayes, education is the most effective means of social control, and family is the most significant agency of social control. E.L. Bernard distinguished between unconscious and conscious means of social control. Unconscious means include customs, traditions, and conventions. Conscious means include techniques consciously developed and employed, for example, propaganda.

3. PURPOSES OF SOCIAL CONTROL

The study of social control is an important aspect of sociology and a significant field of study. It is a unifying factor in the study of human behaviour. According to Kimball Young, the aims of social control are to bring about conformity, solidarity, and continuity of a particular group or society. These aims are good but most individuals who endeavour to control their fellowmen show little perspective in their efforts. They want others to accept the modes of conduct that they themselves prefer. This preference may be based on any factor or experience derived in life and desire to exploit others for one’s own gain, which may be political, personal, or economic reasons.

Some reformers and leaders try to conceal their motives by good reasons in the form of altruistic rationalization. A newspaper advertisement that offers discount to those who make purchases on a particular date is an example of such rationalizations. It is difficult to know and classify the motives of the agents of social control.

The classification of the motives or purposes of the agents of social control are as follows:

- Exploitative, motivated by self-interest

- Regulative based upon habit and the desire for behaviour of the customary types

- Creative or constructive based on social benefit

The results of social control are not always beneficial to a society or to an individual. Even social control for constructive purposes may confuse the public and end in inactivity. Efforts to regulate behaviour in accordance to custom may cause cultural lag, mental conflict, and emotional instability.

4. ESSENTIALS OF SOCIAL CONTROL

- Social control is an influence: The influence maybe exerted through public opinion, coercion, social suggestion, religion, appeal to reason, or any other method.

- The influence is experienced by society: It means that the group is better able to exercise influence over the individual. This group may be the family, the church, the state, the club, the school, the trade union, and so on. The effectiveness of influence, however, depends upon variable factors.

- The influence is exercised for promoting the welfare of the group: The person is influenced to act in the interest of others rather than in accordance with his own individual interests. Social control is exercised for some specific end in view.

- Social control is ancient and universal: It is obvious that social control is present wherever society is a reality. Full conformity to social norms is a myth. As there are deviants in all societies, social control becomes a must. Thus, social control is present in all societies since time immemorial.

Box 19.1 Definitions of Social Control

E.A. Ross: Social control refers to the system of devices whereby society brings its members into conformity with the accepted standards of behaviour.

Henry P. Fairchild: Social control is the sum total of the processes whereby society or any sub-group within society secures conformity to expectation on the part of its constituent units, individuals, and groups.

Karl Mannheim: Social control is the sum of those methods by which a society tries to influence human behaviour to maintain a given order.

W.F. Ogburn and M.F. Nimkoff: Social control refers to the patterns of pressure that a society exerts to maintain order and established rules.

J.S. Roucek: Social control is a collective term used to those processes, planned or unplanned, by which individuals are taught, persuaded, or compelled to conform to the usages and life values of groups.

G.A. Lundberg: Social control designates those social behaviours that influence individuals or groups towards conformity to established or desired norms.

R.M. Maclver and C.H. Page: Social control is meant those methods by which the unity and stability of the entire social system is maintained.

P.H. Landis: Social control is the process by which social order is established and maintained.

J.L. Gillin and J.P. Gillin: Social control is that system of measures, suggestion, restraint, and coercion by whatever means, including physical force, by which a society brings into conformity to the approved pattern of behaviour a sub-group or by which a group moulds into conformity its members.

P.H. Landis: Social control is defined as a social process by which the individual is made group responsive and by which social organization is built and maintained.

Frederick E. Lumley: Social control is defined as the practice of putting forth directive stimuli in the form of accurate transmission of responsibilities and adapting it to gain the control over it, whether voluntary or involuntary. In short, it is an effective will-transference.

Luther L. Bernard: Social control is defined as a process by which stimuli are brought to bear effectively upon some persons or group of persons, thus producing responses that function in adjustment.

Richard LaPiere: Social control is a corrective for inadequate socialization.

5. DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONCEPT OF SOCIAL CONTROL

- Every society has tried to control the behaviour of its members. In the primitive society, social control existed as a powerful force in organizing sociocultural behaviour. From birth to death, man is surrounded by social control of which he may even be unaware.

- The concept of social control has received many formal statements. Although it is foreshadowed in Plato’s Republic (369 BC) and in Comte’s Positive Philosophy (1830–1842), Lester F. Ward in his book Dynamic Sociology (1883) greatly clarified the concept.

- It was in 1894 that the term social control was used for the first time by Albion W. Small and George E. Vincent. These authors discussed the effect of authority upon social behaviour in their book Introduction to the Study of Society.

- In 1894, E.A. Ross became interested in discovering the linchpins that hold society together and developed the germs of the first book in this field.

- E.A. Ross presented a book in 1901 under the name of Social Control wherein he examined fully the concept of social control. His book is a pioneering work in the study of social control. He laid emphasis on social instincts—sympathy, sociability, and a sense of justice, and the means by which the group seeks to exert pressure upon the individual to make him adhere to the folkways and mores.

- In the 1900s, E.A. Ross developed the concept of super-social control by which he meant the domination over society by scheming individuals, who, through propaganda, lobbying, and/or coercive methods, compel society to do their bidding.

- In 1902 appeared C.H. Cooley’s Human Nature and the Social Order, which has been regarded as an admirable supplement to the volume of Ross. He laid emphasis on the effect of group pressure upon the personality of the individual and the necessity for studying a person’s life history in order to understand his behaviour.

- In 1906, William Graham Sumner published a book called Folkways. In this book, which has been called the Old Testament of the sociologists, Sumner laid emphasis on how folkways and institutions limit the behaviour of the individuals. According to him, social behaviour cannot be understood without a study of the folkways and mores that determine whether society will encourage or inhibit any specific item of behaviour.

6. NEED FOR SOCIAL CONTROL

- To maintain old order: It is necessary for every society or group to maintain its social order and this is possible only when its members behave in accordance with that order. An important objective of social control is to maintain the old order. Family helps in the realization of this objective. The aged members of the family enforce their ideas upon the children.

Figure 19.1 Need for Social Control

- To establish social unity: Without social control, social unity would be a mere dream. Social control regulates behaviour in accordance with the established norms that bring uniformity of behaviour and lead to unity among the individuals.

- To regulate or control individual behaviours: No two men are alike in their attitudes, ideas, interests, and habits. Even the children of the same parents do not have the same attitudes; these differences, therefore, need to be regulated.

- Means of social control: E.A. Ross was the first American sociologist to deal at length with social control in a book of that title published in the year 1901. He identified the means of social control (Table 19.1).

TABLE 19.1 Means of Social control Identified by Ross

7. TYPES OF SOCIAL CONTROL

- Direct and indirect control: According to Karl Mannheim, there are two types of control called direct and indirect control. The direct control is done by near and dear ones or with whom we keep physical proximity. Parents, neighbourhood persons, friends, teachers, and playgroup members are the agencies of direct control. With the help of suggestion, punishment, scolding, criticism, appreciation, and reward this form does work. The control done by big organizations such as police, law, state, and courts are the agencies of indirect control.

- Positive and negative control: According to Kimball Young, positive control means control done by giving awards, appreciations, admiration, and certificates. This can be seen in military services and school. Positive control does not mean giving costly items to concerned persons. Giving piece of toffee to children do great work. The negative control consists of physical punishment, fine, criticism, isolation, and so on. Death sentence is an example of physical punishment. For good work, people get first type of awards, and for disobeying rules, they get punishment.

- Informal and formal social control: The social values that are present in individuals are products of informal social control. It is exercised by a society without explicitly stating these rules and is expressed through customs, norms, and mores. Individuals are socialized whether consciously or subconsciously. During informal sanctions, ridicule or criticism causes a straying towards norms. Through this form of socialization, the person will internalize these mores and norms. Traditional society uses mostly informal social control embedded in its customary culture relying on the socialization of its members to establish social order. More rigidly, structured societies may place increased reliance on formal mechanisms.

Informal sanctions may include ridicule, sarcasm, criticism, and disapproval. In extreme cases, sanctions may include social discrimination and exclusion. This implied social control usually has more effect on individuals because they become internalized and thus an aspect of personality.

As with formal controls, informal controls reward or punish acceptable or unacceptable behaviour (i.e., deviance). Informal controls are varied and differ from individual to individual, group to group, and society to society. For example, at a women’s institute meeting, a disapproving look might convey the message that it is inappropriate to flirt with the minister. In a criminal gang, on the other hand, a stronger sanction would be applied in the case of someone threatening to inform to the police.

- Formal social control: Formal social control is expressed through law as statutes, rules, and regulations against deviant behaviour. It is conducted by government and organizations using law enforcement mechanisms and other formal sanctions such as fines and imprisonment. In democratic societies, the goals and mechanisms of formal social control are determined through legislation by elected representatives and thus enjoy a measure of support from the population and voluntary compliance.

In short, formal control is done by big and complicated organizations (law, court, police, and administration), whereas simple and less complicated societies have informal control arrangements (tradition, folkways, religion, and family).

- Autocratic and democratic controls: On the basis of political system, LaPiere has classified it in terms of autocratic and democratic controls. In communist and patriarchal or monarchical societies, autocratic control exist, where keeping one motto in minds, people are exploited and controlled by administrative agencies. In democratic control, people’s own representatives solve the problems through public opinion, conversations, public appeals, and so on. In democracy, control form is more flexible. The rule or administration which is not in favour of welfare of society is removed by common consent.

8. APPLICATION OF SOCIAL CONTROL THEORY

According to the propaganda model theory, the leaders of modern, corporate-dominated societies employ indoctrination as a means of social control. Theorists such as Noam Chomsky have argued that systematic bias exists in the modern media. The marketing, advertising, and public relations industries have thus been said to utilize mass communications to aid the interests of certain business elites. Powerful economic and religious lobbyists have often used school systems and centralized electronic communications to influence public opinion. Democracy is restricted as the majority is not given the information necessary to make rational decisions about ethical, social, environmental, or economic issues.

In order to maintain control and regulate their subjects, authoritarian organizations and governments promulgate rules and issue decrees. However, due to a lack of popular support for enforcement, these entities may rely more on force and other severe sanctions such as censorship, expulsion, and limits on political freedom. Some totalitarian governments, such as the late Soviet Union or the current North Korea, rely on the mechanisms of the police state.

Sociologists not only consider informal means of social control as vital in maintaining public order but also recognize the necessity of formal means, as societies become more complex and for responding to emergencies. The study of social control falls primarily within the academic disciplines of anthropology, political science, and sociology.

9. CUSTOMS

9.1. Introduction

In day-to-day life, man performs several activities. He eats, drinks, thinks, greets his friends, trains the youth, and so on. But he cannot do these activities in whichever fashion he likes. He has to follow the way that has been prescribed by the society. Society expects him to act in a certain way. It lays down the conduct that should be gradually observed. These are customs. They are usages in whatever we do. They are a part of our social heritage. They are passed on from one generation to another with a few changes. They are found in all societies, and they differ widely from place to place and from community to community. They are most important in less advanced communities.

Box 19.2 Definitions of Customs

R.M. MacIver and C.H. Page: Customs are the ways or methods of acting that are sanctioned or recognized by the society.

G.A. Lundeberg et al.: Folkways that persist for several generations and attain a degree of formal recognition are called customs.

Kingsley Davis: Customs refer primarily to practices that have been often repeated by a multitude of generations, and the practices are tend to be followed simply because they have been followed in the past.

E.S. Bogardus: Customs and traditions are group’s accepted means of control that have become well established, that are taken for granted, and that are passed along from generation to generation.

W.A. Anderson and F.B. Parker: The uniform approved ways of acting we follow are customs, which are transmitted from generation to generation by tradition and usually made effective by social approval.

Morris Ginsberg: Customs in fact is not merely a prevailing habit but also a rule or norm of action.

9.2. Nature of Customs

- Customs grow spontaneously: Customs are not a deliberate creation. They grow spontaneously. A custom is a group procedure that has gradually emerged without express enhancement and without any constituted authority to declare it, to apply it, and to safeguard it.

Figure 19.2 Nature of Customs

- Passed from generation to generation: Customs are passed along from generation to generation, mostly unconsciously. These are the uniform approved ways of acting, which are transmitted from generation to generation by tradition.

- Origin of customs is obscure: Nothing can be stated in certainty as to the exact origin of custom. Many customs arose to satisfy the fundamental needs of man, especially those connected with his self-preservation, sex life, and procreation. Some of the customs were learned by imitating other people. Many of them came as adjustments to changing situations. Thus, the origin of customs is obscure and cannot be dated.

- Customs are varied: Customs are relative in nature. They vary from society to society. Although universal, rich varieties may be observed in customary practices.

- Objects of customs are not clear: The ends or objects of many of the customs are not clear. A custom need not have any specific purpose to serve. It may have arisen as a compromise or fusion between diverse customs or through some purely instinctive mode of reaction or imitation of external model.

- Customs are relatively durable: Customs, when compared with habits, folkways, fashions, and so on, are found to be rather long-lasting. For whatever purposes they are instituted, if one established, observing them in some degree becomes an end itself.

- Not all customs are irrational: It may be admitted that there are some customs that cannot be justified on any utilitarian or ethical ground. For instance, cancelling one’s journey) because a cat has crossed the path, performing shraddha for the dead, and so on may be branded as irrational. However, it does not mean that all customs are irrational. Saluting the national flag, respecting one’s parents and elders, entertaining one’s friends and relatives on a festival day, and so on are justifiable on social and psychological grounds.

9.3. Functions of Customs

- Customs regulate social life: Customs are a very powerful means of control. In simple, small, and homogeneous communities, customs are so powerful that no one can escape their grip. They are the first requisite of society and the prime condition of social life of man.

Figure 19.3 Functions of Customs

- Customs are the repository of social heritage: Customs, in fact, are the storehouse of our social heritage. They preserve our culture and transmit it to the succeeding generations. They provide stability to social order. They help in adjusting too many social problems. They provide for continuity of the social order.

- Customs mould personality: Customs play an important role in moulding one’s personality. From birth to death, man is a slave of customs. He is born out of marriage, a custom; he is brought up according to the customs; and when he dies, he is given last rites as laid down by the customs. Customs mould his attitudes and ideas.

- Customs save individual effort: Readymade patterns of behaviour suitable for different occasions are available through customs. The language a child learns, the worship pattern a child follows, the relationships the child enters into, the occupations into which he or she is initiated—all are provided by customs. Thus, the individual is spared the effort of re-inventing the wheel.

- Customs bring about solitary in the group: Customs bring men together, assimilating their actions to the accepted standards. They control the individualistic and egoistic tendencies of human beings.

9.4. Characteristics of Customs

- Customs are accepted and established forms of behaviour.

- Folkways when continued over generations take the form of customs.

- Customs are traditional.

- They are effective means of control because those who go against customs are punished.

- They are regulatory in nature.

- They are unwritten codes of behaviour.

- They may change gradually.

9.5. Customs and Habits

Customs and habits are very closely related. According to R.M. MacIver and C.H. Page, habits mean an acquired facility to act in a certain manner without resort to deliberation and thought. Persons tend to react in the manner that they have been accustomed to, for example, smoking, drinking coffee or tea regularly, reading newspaper daily, drinking liquors, morning exercises, shaving daily in the morning, and so on.

Box 19.3 Definitions Of Tradition

Morris Ginsberg: By tradition, it is meant the sum of all ideas, habits, and customs that belong to people and are transmitted from one generation to another.

James Devers: Tradition is the body of laws, customs, stories, and myths transmitted or handed down orally from one generation to another.

Habits are a second nature with us. Once they develop, they tend to become permanent. Then it becomes difficult for us to act in a way different from the habitual ones. A habit is a strongly established and deeply rooted mode of response. As MacIver and Page have pointed out, habit is the instrument of life. It economizes energy, reduces drudgery, and saves the needless expenditure of thought. William James considers it a preciously conservative agent.

9.6. Difference between Custom and Habits

- Customs are a social phenomenon, whereas habits are an individual phenomenon.

- Customs are socially recognized. Habits do not require such recognition.

- Customs are normative in nature. They have the sanction of society. Habits are not normative and require no external sanction.

- Customs contribute to the stability of social order. Hence, they are of great social importance. The importance of habits is only for the individual who is accustomed to them.

- Customs are socially inherited, whereas habits are learned individually.

Some more differences have been enlisted in Table 19.2.

TABLE 19.2 Differences between Customs and Habits

| Custom | Habit |

|---|---|

| It has an external sanction. | It has no external sanction. |

| It is a social phenomenon. | It is an individual phenomenon. |

| It is inherited. | It is learned. |

| It is socially recognized. | It is not socially recognized. |

| It maintains social order. | It facilitates individual activity. |

| It is normative. | It is not normative. |

| It has got great social significance. | It is more of personal importance. |

| It exists as a social relationship. | It is formed in isolation. |

| It cannot exist unless the corresponding habit is inculcated into the new generation. | It can exist without customs. |

| It creates habits. | It creates customs. |

9.7. Conclusion

Custom is used as synonymous with habit, but there is a vital difference between the two. Habit is a personal phenomenon, whereas custom is a social phenomenon. A custom is formed on the basis of a habit gaining the sanction and influence of society and therefore has a social significance, which is peculiar to it. Customs, folkways, and mores are the elementary processes in the development of society. They are found in all cultures and help the individual to adopt himself to the conditions of life.

10. TRADITION

10.1. Characteristics of Tradition

- Traditions are clusters of folkways, customs, and ideas.

- They are socially accepted.

- They are handed over from generation to generation.

- They may or may not be legal.

- They may be changed through education and legislation.

10.2. Importance of Tradition

- Traditions are useful in personality development.

- They bring about homogeneity in social life.

- They may form the core of many laws and social legislations.

- They assist in social adjustments.

10.3. Modernization of Indian Tradition

Modernization is a composite concept. It is also an ideological concept. The models of modernization co-vary with the choice of ideologies. The composite nature of this concept renders it pervasive in the vocabulary of social sciences and evokes its kinship with concepts like development, growth, evolution, and progress. In the book on Essays on Modernization in India, Yogendra Singh has analysed the varied and complex processes involved in the modernization in India, the forces released by it, and their bearing on the stability, creativity, and development in India as a dynamic nation and composite civilization.

The emphasis on historicity in preference to universality defining the context of modernization, the pre-eminence of structural changes in society to render the adaptive process of modernization successful in the developing countries, particularly India, and the eclectic nature of cultural and ideological response of India to the challenges of modernization represent some of the unifying principles. Singh portrays the challenges and contradictions that India encounters in the course of its modernization.

11. FOLKWAYS

11.1. Introduction

The literal meaning of the term folkways is the ways of the folk. Folk means people or group, and ways refers to the ways in which a group does things. Thus, these are the ways of the folk, that is, social habits or social expectations that have arisen in the daily life of the group. They are accepted modes of conduct in a society. The standards of every society are the result of a long experience achieved in the course of several generations. They are not developed consciously. They include popular habits, conventions, forms of etiquette, fashion, morals, and so on. Folkways differ from group to group. For example, women in India grow their hair long, whereas those in Europe cut it short. Even in dress and in eating habits, we can notice differences. Folkways are the simplest ways of satisfying the interest of man. They become part of our nature. However, we may modify them to meet a change in the conditions of life. Thus, folkways concerning religion, property, and marriage change slowly.

11.2. Characteristics of Folkways

- Spontaneous origin: Folkways arise spontaneously. They are not deliberately planned or designed. They are developed out of experience. Folkways are unplanned and uncharted. It is very difficult to trace the origin or the originator.

- Approved behaviour: These are the organized ways of behaviour. The group accords recognition to certain ways and rejects certain others. Only such ways of behaviour as have been approved by the group are called folkways.

- Distinctiveness: Folkways differ from group to group. A wide variety among folkways in different societies is found. These are ways of the group and may be unique to one group. Thus, there is considerable variation in the folkways between groups.

- Hereditary: Many of the folkways are hereditary in nature. They are passed on from one generation to another. An individual receives folkways from his ancestors.

R.M. MacIver: Folkways are the recognized or accepted ways of behaviour.

Don Martindale and Elio D. Monachesi: Folkways are habitual ways of doing things, which arise out of the adjustment of persons to place.

Arnold W. Green: Those ways of acting that are common to a society or group and that are handed down from one generation to the next are known as folkways.

John A. Gillin and John P. Gillin: Folkways are defined as behaviour patterns of everyday life, which generally arise unconsciously in group without planned or rational thoughts.

George A. Lundberg: Folkways are that typical or habitual beliefs, attitudes, and styles of conduct observed within a group or community.

F.E. Merrill: Folkways are literally the ways of the folk, that is, social habits or group expectation that have arisen in the daily life of the group.

P.B. Horton and C.L. Hunt: Folkways are simply the customary normal, habitual ways a group does things.

- Dynamic: Folkways are dynamic. They resist change and yet undergo change. Folkways connected with the belief and practices regarding family, property, marriage, and so on resist change more than those connected with the economic functions of a group.

- Informal sanction: The sanctions of the folkways are informal. There are neither formal agencies nor rules to take note of violation of folkways. However, there are certain standardized procedures for punishing or otherwise discouraging the violator. Gossip and ridicule are directed against their violation.

Figure 19.4 Characteristics of Folkways

11.3. Importance of Folkways

- Folkways are the foundation of every culture. When fully assimilated, they become personal habits. They save much of our energy and time. They are generally observed by the people. Hence, people are free to solve problems and strive towards individual and collective goals.

- Folkways solve problems and strive towards individual and collective goals. They have reduced much of our mental strain and nervous tension by helping us to handle social relations in a comfortable way.

- Folkways have become a universal characteristic of human societies. No society does or could exist without them. Hence, they constitute an important part of the social structure.

- Folkways contribute to the order and stability of social relations. Infants learn the folkways from the elders as naturally as they grow up. The folkways become a part and parcel of the personality of the infants through the process of socialization. They learn different folkways at different stages relevant to their class, caste, and racial, ethnic, and other status.

- Folkways arise as solutions to many of the problems of social living. Without reasoning, we follow folkways when we are faced with identical situations. No member of the group ever questions folkways nor is anyone needed to enforce a folkway.

- Folkways regulate behaviour. They are one of the informal means of social control. They are binding, and hence, they must be followed. They predict behaviour. We feel some order in social life because of folkways. They regulate every phase of life and every activity of man.

- Folkways encourage interdependence. By conforming to them, man acts to ensure group welfare.

- Folkways teach man to respect others’ interests. Moreover, in social interactions, folkways, which are socially approved ways of behaviour, are adopted, thus maintaining social solidarity.

- Folkways are transmitted from generation to generation and thus form a part of cultural heritage. They are in fact a repository of culture; planning and social progress has to be based on them. Hence, pervading is the influence of folkways that to make any law or to bring social change, they have to be taken into consideration.

11.4. Conclusion

Sumner conceived culture in terms of folkways and mores. Thus, according to him, the concept of folkways has got a comprehensive meaning. The term is more general and wider in character than customs and institutions.

Man is born with thirst to satisfy his needs. His needs are numerous and the ways in which he tries to satisfy them also vary. Thus, folkways find their origin in human needs. With arise in needs, the efforts to satisfy them arise too. Folkways include customs, popular habits, conventions, etiquettes, fashions, and so on. They consist of all other innumerable modes of behaviour that men have evolved and continue to evolve to facilitate the business of social living. In brief, the concept of folkways includes all the ways that are created unconsciously and spontaneously and are passed from generation to generation.

12. NORMS

Norm, in popular usage, means a standard. Social norms represent standardized generations. These generations are related to expected modes of behaviour. Norms are concepts that have been evaluated by the group and incorporate value judgements. Thus, norms are based on social values that are justified by moral standards. A norm is a pattern setting limits on individual behaviour. It does not refer to an average or central tendency of human being. Norms simply denote expected behaviour to which normal value is attached. They set out normative order of the group. They determine, guide, control, and also predict human behaviour. They are blueprints of behaviour.

Box 19.5 Definitions of Norms

Leonard Broom and Philip Selznick: Norms are blueprints for behaviour, thereby setting limits within which the individuals may seek alternate ways to achieve their goals.

M. Sherif and C.W. Sherif: Norms are standardized generalizations concerning expected modes of behaviour.

P.F. Secord and C.W. Beckman: A norm is a standard of behaviour expectation shared by group members against whom the validity of perceptions is judged and the appropriateness of feeling and behaviour is evaluated.

Harry M. Johnson: A norm is an abstract pattern held in the mind that sets certain limits of behaviour.

E.A. Ross: Norms are standards by which specific human acts are approved or condemned. They are either prescriptive, thereby demanding certain kinds of behaviour, or proscriptive, thereby requiring the abstinence from tabooed sorts of behaviour.

12.1. Nature of Norms

- Norms are universal: Norms are millions of years old and are found in all societies. A normless society is a myth. A society free from normative control, if any, is a society of beasts or devils. For their smooth functioning, all societies require norms. In all societies—civilized as well as uncivilized, Eastern as well as Western, traditional as well as modern—norms are found.

- Norms are standard: A norm is a rule or standard that governs our conduct in the social situation in which we participate. It is a standard of behavioural expectations. It is a standard to which we are expected to conform irrespective of whether we actually do so or not. For example, monogamy is a standard to which all must conform. However, whether one is monogamous or polygamous depends upon cultural specifications.

- Norms are not a statistical average: It should be remarked that norm is not a statistical average. It is not mean, median or mode. It refers not to the behaviour of a number of persons in a specific social situation but instead to the expected behaviour—the behaviour that is considered appropriate in that situation.

Figure 19.5 Nature of Norms

- Norms incorporate value judgement: A norm is a social expectation. Norms are the concepts that have been evaluated by the group and incorporate value judgements. They are based on social values and are justified by normal standards. By looking to norms, a person can know what is expected of him/her in a particular situation. Thus, it is in terms of norms that we judge whether some action is right or wrong, good or bad, wanted or unwanted, and expected or unexpected.

- Norms are related to the factual world: One can see two types of order in every society. The first one is the normative order, which states how one should or ought to behave, and the other one is the factual order, which is related to and is based on the actual behaviour of the people. A society regulates the behaviour of its members with the help of the normative system.

- Social order is inherently normative: Social order presupposes the existence of a normative order. Normative order has evolved as a part of human society because it helped to satisfy the fundamental societal needs. Thus, it has enabled the societies and hence the human species to survive.

- Norms are generally internalized: Norms are generally internalized, that is, made part of one’s personality. Thus, they gain automatic expression. Internalization of norms becomes easy because one learns them through socialization. Sometimes, socialization is defined as a process of internalization of norms.

- Norms are relative: Norms do not apply equally to all members of a society or to all situations. They vary from society to society and differ with age, sex, occupation, social status, and so on. They are adjusted to the positions people hold in the social order.

- Norms carry a sense of obligation: All culturally transmitted behaviour patterns carry a sense of obligation and are therefore normative. If an individual learns to speak a language, there is an obligation to speak it correctly.

- Norms have sanctions: Sanctions are simply the means of controlling human behaviour. These are the supporters of the norms. They may take the form of both reward and punishment. These are used to pursue or force an individual or group to conform to social norms.

12.2. Importance of Social Norms

- The standards of behaviour contained in the norms give order to social relations; interaction goes on smoothly if the individuals follow the group norms.

Figure 19.6 Importance of Social Norms

- The normative order makes the factual order of human society possible.

- Being the accepted standards of social behaviour, norms regulate the behaviour of the individual members of the society.

- Norms regulate and control the individual as well as the social organization.

- The normative system gives to society a cohesion without which social life is not possible.

- Norms help the individual members of the society to fulfil his or her social needs properly.

- They help in the maintenance of social aims and objectives. They make it possible to uphold the values of the society.

- They determine and guide the members of society in initiating the judgement of others and their own.

12.3. Conclusion

Norms are related to the factual world. They take into account the factual situation. They are not abstract representation and imaginary concepts. Social norms have their sanctions. Whenever a social norm is violated, it attracts punishment to its doer. The reward and punishment system is a common feature of the social norms of a society.

13. MORES

The word ‘mores’ is a Latin term. It represented the ancient Roman’s most respected and even sacred customs. ‘More’ refers to the singular form of mores. However, in sociological usage, the singular of mores is generally not used. The term mores was introduced to sociological literature by William G. Sumner.

It is currently being used as almost synonymous with morals. The mores represent yet another category of norms. Mores is a term used to denote behaviour patterns that are not only accepted but are also prescribed. The mores are much stronger norms.

Box 19.6 Definitions of Mores

Edward Sapir: The term mores is best reserved for those customs that connote a fairly strong feeling of the rightness or wrongness of mode of behaviour.

R.M. MacIver and C.H. Page: When the folkways have added to themselves conceptions of group welfare and standards of right and wrong, they are converted into mores.

J.L. Gillin and J.P. Gillin: Mores are those customs and group routines that are thought by the members of the society to be necessary to the group’s continued existence.

Ellen C. Semple: We can say when the folkways clearly represent the group standards, the group sense of what is fitting, rightness, or wrongness of mode of the behaviour, they are called mores.

13.1. Types of Mores

Mores are broadly classified into two categories—positive and negative mores. Table 19.3 describes these categories.

TABLE 19.3 Types of Mores

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Positive mores | Positive mores always prescribe behaviour patterns. They represent the dos. They give instructions and provide guidance for the people to behave in a particular way. Examples include respecting the elders, protecting children, taking care of the diseased and the aged, loving one’s country, doing service to society, worshipping God, speaking the truth, and so on. |

| Negative mores | Negative mores proscribe behaviour patterns. They represent the don’ts. They are often called taboos and forbid or prohibit certain behaviour patterns. Examples include don’t appear before people without clothes, don’t steal, don’t commit adultery, don’t tell lies, and so on. |

13.2. Characteristics of Mores

- Mores are regulators of social life: Mores represent the living character of the group or community. They are always considered as right by the people who share them. They are morally right and their violation is morally wrong.

- Mores are relatively more persistent: Mores are relatively long-lasting than ordinary folkways. In fact, they even lead to conservative elements in society putting up resistance to change. For example, people at one time resisted the efforts of the lawmakers to abolish the so-called mores such as slavery, child marriage, human sacrifice, practice of sati, and so on.

Figure 19.7 Types of Mores

- Mores vary from group to group: Mores have not always been uniform. What is prescribed in one group is prohibited in another. Eskimos, for example, often practice female infanticide, whereas such a practice is strictly forbidden in the modern societies.

- Mores are often backed by values and religion: Mores normally receive the sanction and backing of values and religion. With this, they become still more powerful and binding. Mores backed by religious sanctions are strongly justified by people. Ten Commandments, for example, are considered to be important and essential for the Christians because they are backed by their religion.

13.3. Functions of Mores

- Mores determine much of our individual behaviour: Mores bring direct pressure on our behaviour. They mould our character and restrain our tendencies. They act as powerful instruments of social control.

- Mores identify the individual with the group: Mores are the means by which the individual gains identification with his fellowmen. As a result, he maintains social relations with others that are very essential for satisfactory living.

- Mores are guardians of social solidarity: Mores bring the people together and weld them into a strong cohesive group. Those who share common mores also share many other patterns of behaviour. Every group or society has its own mores.

- Mores are helpful in framing laws: Mores provide the basis for making laws that govern our social relations. The law usually codifies important norms including mores that already exist.

Figure 19.8 Functions of Mores

13.4. Conclusion

When folkways grow to the stature of having moral obligations on the members of the society, they become mores. Mores are important for the welfare of the society. While folkways are not obligatory, mores are.

14. LAW

All societies are dynamic, not static. They are growing wholes. With growth, societies become big or complex. In such societies, mere public opinion, informal force, normal conscience, and so on cannot ensure order. In the face of growing social complexity and increasing group size, the judicial functions of customary laws cease to be sufficient. Formal controls are the most obvious type of social control as internalized controls and informal external controls are usually non-verbal and involve no manifest show of force. They are also the most costly ones, and they may be among the least effective of the social control mechanisms. The most apparent example of formal social control is law. Laws are found only in societies that are politically organized.

Box 19.7 Definitions of Law

J.S. Roucek: Laws are a form of social rule emanating from political agencies.

Roscoe Pound: A law is an authoritative canon of value laid down by the force of politically organized society.

Ian Robertson: A law is simply a rule that has been formally enacted by a political authority and is backed by the power of the state.

R.M. MacIver and C.H. Page: Law is the body of rules that are recognized, interpreted, and applied to a particular situation by the courts of a state.

E.A. Ross: A law is the specialized and highly finished engine of social control employed by society.

Anthony Giddens: Law is a rule of behaviour established by a political authority and backed by state power.

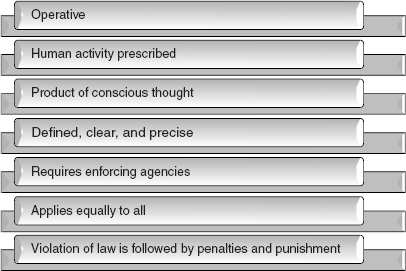

14.1. Characteristics of Law

- Laws are not as universal as folkways or customs. All societies have folkways and mores but not all societies have laws. Only in politically organized societies called states, laws are found to be operative.

- Laws are the general conditions of human activity prescribed by the state for its members.

- Law is called law only if enacted by a proper law-making authority. It is a product of conscious thought, deliberate attempts, and careful planning.

Figure 19.9 Characteristics of Law

- It is defined, clear, and precise.

- It applies equally to all without exception in identical circumstances.

- Violation of law is followed by penalties and punishment. Informal controls may reward good behaviour (with smiles, compliments, and honours) and punish bad behaviour (with sanctions like guilt, frown, moral lecture, and withholding friendship). The law, on the other hand, more often involves negative sanctions of punishment.

- Laws are always written down and recorded in some fashion. Hence, they cannot appear in non-literate society.

- They are not the result of voluntary consent of persons against whom they are directed.

- A law does not operate on its own. It requires enforcing agencies. The formation of law, its interpretation and implementation, and giving punishment to its offenders—all these tasks represent a specialized work that can be done only by the people who are seasoned in the field.

- Law declares that all the people are equal before it. It means laws are applicable equally to all the people who live in a particular territory.

14.2. Functions of Law

- If the beastly qualities and unrestrained inhuman tendencies reign supreme in men, they will affect the orderliness of the society adversely. These tendencies are doubly dangerous. They are dangerous to the personal interests of those in whom they are present, and they are harmful to the interests, welfare, and security of other people in the society. Law eliminates and suppresses the homicidal activities of the individuals.

- People are normally particular about safeguarding their interests. However, in their effort to do so, they should not pose threat or danger to the interests and welfare of others. It is the task of law to ensure safety and security to all. Laws persuade and insist on the individual to pay attention to the rights of others and to act in cooperation with them.

14.3. Conclusion

The law, enacted by the state, is probably the most important means of social control in modern times. It is one of the most explicit and concrete forms of social control, although by no means the only or the most influential form. In modern societies, the law is always written and ordinarily includes specification for penalties imposed for violations, which are themselves a part of the law.

15. EDUCATION

The term education is derived from Latin word educare, which literally means to bring up, and is connected with the verb educere, which means to bring forth. The idea of education is not merely to impart knowledge to the pupil in some subjects but also to develop in him or her those habits and attitudes that he or she may successfully face the future with. Education is a process of socialization.

Along with knowledge, values, ideals, and morals are imparted to the individuals. The society aims at moulding and changing the behaviour of the growing individuals through education. Education is one of the basic activities of people in all human societies. The continued existence of a society depends upon the transmission of culture to the young. It is essential that every new generation must be given training in the ways of the group so that the same tradition will continue.

Emile Durkheim: Education is the socialization of the younger generation. It is a continuous effort to impose on the child the ways of seeing, feeling, and acting that the child could not have arrived at spontaneously.

William G. Sumner: Education is an attempt to transmit to the child the mores of the group, so that he can learn which conduct is approved and which is disapproved; … how he ought to behave in all kinds of cases; what he ought to believe and reject.

A.W. Green: Historically, it (education) has meant the conscious training of the young for the later adaptation of adult roles. By modern convention, however, education has come to mean formal training by specialists within the formal organization of the school.

Samuel Koenig: Education may also be defined as the process whereby the social heritage of a group is passed on from one generation to another as well as the process whereby the child becomes socialized, that is, learns the rules of behaviour of the group into which he is born.

15.1. Education as a Means of Social Control

- Education as an instrument of socialization: Socialization is the process of providing social training to the individuals by controlling their animal-like nature. Education is one of the established means of society that has the objective of controlling the socialization process. The school and other institutions have come into being in place of family to complete the socialization process. The school devotes much of its time and energy to matters such as cooperation, good citizenship, doing one’s duty, and upholding the law.

- Formation of social personality: Individuals must have personalities shaped or fashioned in ways that fit into the culture. Everywhere, education has the function of the formation of social personalities. It helps in transforming culture through proper moulding of social personalities. In this way, it contributes to the integration of society. It helps men to adapt themselves to their environment, to survive, and to reproduce themselves.

- Reformation of attitudes: One of the challenges before social control is regulating and reforming antisocial behaviour. The very root of this behaviour is the human mind. Hence, human mind is to be shaped and the child is to be helped in developing the right attitudes. In fact, education aims at the reformation of wrong attitudes already developed by the children. For various reasons, the child may have absorbed a host of wrong attitudes, beliefs and disbeliefs, loyalties and prejudices, jealousy and hatred, and so on. These are to be reformed.

- Regulation by imparting new ideas, values, and norms: The curriculum of a school, its extracurricular activities, and the informal relationships among students and teachers communicate social skills and values. Through various activities, a school imparts values such as cooperation or team spirit, obedience, and fair play. Education, in a broad sense, has become a vital means of social control from infancy to adulthood.

Figure 19.10 Education as a Means of Social Control

- Means to control political system: Education is often used to manipulate the existing political system. It is used to support and stabilize the democratic system. It fosters participation in democracy. Participant democracy in any large and complex society depends on literacy. Literacy allows full participation of the people in democratic and effective voting. Literacy is a product of education. Educational system has, thus, economic as well as political significance.

- Education conditions occupational career of the individual: Education is often regarded as an instrument of livelihood. It has a practical end also. It should help the adolescent in earning his livelihood. In fact, education, today, has come to be seen as nothing more than an instrument of livelihood. Although it is wrong to view this as the only function of education, it cannot be gainsaid that education must prepare the students for future occupational positions.

- Conditions younger generation culturally: Education acts as an integrating force in society by communicating the values that unite different sections of society. Especially in a multigroup society, it is not possible for the family on its own to provide the child the essential knowledge of the skills and values of the wider society.

16. DEVIANCE

Deviance is defined as any violation of norms, whether the infraction is as minor as driving over the speed limit or as serious as murder. According to sociologist Howard S. Becker, it is not the act itself but the reactions to the act that make something deviant. According to Horton and Hunt, deviance is given to any failure to conform to customary norms. Louise Weston defines deviance as behaviour that is contrary to the standards of conduct or social expectations of a given group or society. M.B. Clinard suggests that the term deviance should be reserved for those situations in which the behaviour is in a disapproved direction and of sufficient degree to exceed the tolerance limit of society.

Different groups have different norms, what is deviant to some is not deviant to others. This principle holds both within a society and across cultures. Thus, another group within the same society may consider acts acceptable in one culture or in one group within a society may consider acts deviant in another culture.

This principle also applies to a specific form of deviance known as crime, which is the violation of rules that have been written into law. In the extreme, an act that is applauded by one group may be so despised by another group that it is punishable by death. Making a huge profit on business deals is one example. Americans like Donald Trump and Warren Buffet are admired. In China, however, until recently, this same act was considered a crime called profiteering. Those found guilty were hanged in a public square as a lesson to all.

Sociologists use the term deviance to refer to any act to which people respond negatively. When sociologists use this term, it does not mean that they agree that an act is bad, just that people judge it negatively. To sociologists, all of us are deviants of one sort or another, for we all violate norms from time to time.

Sociologist Erving Goffman (1963) used the term stigma to refer to characteristics that discredit people. These include violations of norms of ability (blindness, deafness, and mental handicaps) and norms of appearance (a facial birthmark, a huge nose, and so on).

Secret deviants are people who have broken the rules but whose violation goes unnoticed or, if it is noticed, it prompts those who notice to look the other way rather than reporting it as violation.

Witch-hunt is a campaign to identify, investigate, and correct behaviour that has been defined as undermining a group or country. Usually, this behaviour is not the real cause of a problem but is used to distract people’s attention from the real cause or to make the problem seem manageable.

The falsely accused are people who have not broken the rules but are treated as if they have. The ranks of the falsely accused include victims of eyewitness errors and police cover-ups; they also include innocent suspects who make false confessions under the pressure of interrogation.

Sociologist Kai Erikson (1966) identified a particular situation in which people are likely to be falsely accused of a crime when the wellbeing of a country or a group is threatened. The threat can take the form of an economic crisis, a moral crisis, a health crisis, or a national security crisis. At times like these, people need to identify a clear source of the threat. Thus, whenever a catastrophe occurs, it is common to blame someone for it.

17. INFLUENCE OF SOCIAL CONTROL ON HEALTH BEHAVIOURS

The social environment provides an important context for health and health behaviour across the lifespan as well as a potential point of intervention for increasing physical activity. However, age and sex interacted with social control such that more positive social control was associated with more frequent physical activity for younger men. Furthermore, more positive and negative social controls were significantly associated with less frequent physical activity for older men, whereas social control was not associated with physical activity among women. While younger men may be encouraged toward healthier behaviours by positive social control messages, social control attempts may backfire when targeting older men.

The health professionals and intimate social partners should be discouraged from using negative social control strategies because of the potential to induce negative affect, because these strategies may be ineffective for women and younger men, and because these strategies may be counterproductive for older men. Instead, it might be more appropriate to use positive social control strategies, particularly, for younger male targets in order to maintain feelings of support and positive affect while encouraging health behaviour change. On the other hand, alternative strategies should be pursued for improving the health and fitness of women and older adults. For example, bolstering self-efficacy may provide an efficacious strategy within these populations.

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Social control is, thus, a regulation of individual and group behaviour.

- It may be affected through informal means such as customs and mores or formal ones such as law and education.

- Traditional societies rely more on the former, whereas modern, democratic ones are governed primarily by the latter.

EXERCISES

I. LONG ESSAY

- Define social control; explain the meaning and purposes of social control.

- Describe the influence of social control on health behaviours.

II. SHORT ESSAY

- Discuss the essentials of social control.

- Explain the development of the concept of social control.

- Describe the need of social control.

- Enumerate the types of social control.

- Discuss the application of social control theory.

- Explain the nature and functions of customs.

- Explain the characteristics and importance of folkways.

- Explain the characteristics and functions of mores.

III. SHORT ANSWERS

- Explain the characteristics of customs.

- Explain traditions.

- Explain nature of norms.

- Explain the characteristics and functions of law.

- Explain education as the means of social control.

IV. MULTIPLE CHOICE QUESTIONS

- According to ________________, social control refers to the system of devices whereby society brings its members into conformity with the accepted standard of behaviour.

- Karl Manheim

- E.A. Ross

- Ogburn

- Nimkoff

- Which of the following is the means of social control?

- belief

- folkways

- mores

- all of these

- Social shared expectation is referred as ________________.

- need

- nature

- norm

- sanction

- Folkways that persist for several generations and attain a degree of formal recognition are called ________________.

- custom

- moral

- social value

- law

- The recognized or accepted way of behaviour is ________________.

- norm

- need

- folkway

- tradition

- Which are the characteristics of law?

- Laws are not universal

- Law is called law only if enacted by a proper law-making authority

- Laws are always written down and recorded in some action

- All of these

- Which of the following refers to formal ways of social control?

- education

- custom

- more

- folkway

- Which of the following refers to informal ways of social control?

- law

- education

- family

- force

- The action that is oriented to a social norm and falls within the brand of behaviour permitted by norms is called ________________.

- deviance

- conformity

- tradition

- habits

- Which are the two types of social control?

- formal and informal

- positive and negative

- in-group and out-group

- none of these

ANSWERS

1. b 2. d 3. c 4. a 5. c 6. e 7. a 8. c 9. b 10. a

REFERENCES

- Aubert, V. (1969). Elements of Sociology (London: Heinemann Educational Books Ltd).

- Bhushan, V., Sachdeva, D.R. (2000). An Introduction to Sociology (Allahabad: Kitab Mahal).

- Cooley, Charles H. (1964). Human Nature and the Social Order (New York: Schocken).

- De Vos, George A. (ed.) (1973). Socialization for Achievement: Essays on the Cultural Psychology of the Japanese (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press).

- Dobriner, William M. (1969). Social Structure and Systems (Santa Monica, CA: Goodyear).

- Goode, William J. (1979). Principles of Sociology (New Delhi: Tata McGraw-Hill).

- Jones, Marshall E. (1949). Basic Sociological Principles (Boston, MA: Ginn and Co.).

- MacIver, R.M., Page, C.H. (1971). Society: An Introductory Analysis (London: Macmillan).

- Ogburn, W.E., Nimkoff, M.F. (1972). A Handbook of Sociology (New Delhi: Eurasia Publishing House).

- Roucek, Joseph S. and Associates (1947). Social Control (New York: D. Van Nostrand Co.).

- Yorburg, Betty (1982). Introduction to Sociology (New York: Harper and Row).

- Young, K., Mack, Raymond W. (1962). Systematic Sociology: Text and Readings, Sociology and Social Life and Principles of Sociology (New Delhi: Affiliated East-West Press).