4. Understanding Quality Attributes

Between stimulus and response, there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

—Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning

As we have seen in the Architecture Influence Cycle (in Chapter 3), many factors determine the qualities that must be provided for in a system’s architecture. These qualities go beyond functionality, which is the basic statement of the system’s capabilities, services, and behavior. Although functionality and other qualities are closely related, as you will see, functionality often takes the front seat in the development scheme. This preference is shortsighted, however. Systems are frequently redesigned not because they are functionally deficient—the replacements are often functionally identical—but because they are difficult to maintain, port, or scale; or they are too slow; or they have been compromised by hackers. In Chapter 2, we said that architecture was the first place in software creation in which quality requirements could be addressed. It is the mapping of a system’s functionality onto software structures that determines the architecture’s support for qualities. In Chapters 5–11 we discuss how various qualities are supported by architectural design decisions. In Chapter 17 we show how to integrate all of the quality attribute decisions into a single design.

We have been using the term “quality attribute” loosely, but now it is time to define it more carefully. A quality attribute (QA) is a measurable or testable property of a system that is used to indicate how well the system satisfies the needs of its stakeholders. You can think of a quality attribute as measuring the “goodness” of a product along some dimension of interest to a stakeholder.

In this chapter our focus is on understanding the following:

• How to express the qualities we want our architecture to provide to the system or systems we are building from it

• How to achieve those qualities

• How to determine the design decisions we might make with respect to those qualities

This chapter provides the context for the discussion of specific quality attributes in Chapters 5–11.

4.1. Architecture and Requirements

Requirements for a system come in a variety of forms: textual requirements, mockups, existing systems, use cases, user stories, and more. Chapter 16 discusses the concept of an architecturally significant requirement, the role such requirements play in architecture, and how to identify them. No matter the source, all requirements encompass the following categories:

1. Functional requirements. These requirements state what the system must do, and how it must behave or react to runtime stimuli.

2. Quality attribute requirements. These requirements are qualifications of the functional requirements or of the overall product. A qualification of a functional requirement is an item such as how fast the function must be performed, or how resilient it must be to erroneous input. A qualification of the overall product is an item such as the time to deploy the product or a limitation on operational costs.

3. Constraints. A constraint is a design decision with zero degrees of freedom. That is, it’s a design decision that’s already been made. Examples include the requirement to use a certain programming language or to reuse a certain existing module, or a management fiat to make your system service oriented. These choices are arguably in the purview of the architect, but external factors (such as not being able to train the staff in a new language, or having a business agreement with a software supplier, or pushing business goals of service interoperability) have led those in power to dictate these design outcomes.

What is the “response” of architecture to each of these kinds of requirements?

1. Functional requirements are satisfied by assigning an appropriate sequence of responsibilities throughout the design. As we will see later in this chapter, assigning responsibilities to architectural elements is a fundamental architectural design decision.

2. Quality attribute requirements are satisfied by the various structures designed into the architecture, and the behaviors and interactions of the elements that populate those structures. Chapter 17 will show this approach in more detail.

3. Constraints are satisfied by accepting the design decision and reconciling it with other affected design decisions.

4.2. Functionality

Functionality is the ability of the system to do the work for which it was intended. Of all of the requirements, functionality has the strangest relationship to architecture.

First of all, functionality does not determine architecture. That is, given a set of required functionality, there is no end to the architectures you could create to satisfy that functionality. At the very least, you could divide up the functionality in any number of ways and assign the subpieces to different architectural elements.

In fact, if functionality were the only thing that mattered, you wouldn’t have to divide the system into pieces at all; a single monolithic blob with no internal structure would do just fine. Instead, we design our systems as structured sets of cooperating architectural elements—modules, layers, classes, services, databases, apps, threads, peers, tiers, and on and on—to make them understandable and to support a variety of other purposes. Those “other purposes” are the other quality attributes that we’ll turn our attention to in the remaining sections of this chapter, and the remaining chapters of Part II.

But although functionality is independent of any particular structure, functionality is achieved by assigning responsibilities to architectural elements, resulting in one of the most basic of architectural structures.

Although responsibilities can be allocated arbitrarily to any modules, software architecture constrains this allocation when other quality attributes are important. For example, systems are frequently divided so that several people can cooperatively build them. The architect’s interest in functionality is in how it interacts with and constrains other qualities.

4.3. Quality Attribute Considerations

Just as a system’s functions do not stand on their own without due consideration of other quality attributes, neither do quality attributes stand on their own; they pertain to the functions of the system. If a functional requirement is “When the user presses the green button, the Options dialog appears,” a performance QA annotation might describe how quickly the dialog will appear; an availability QA annotation might describe how often this function will fail, and how quickly it will be repaired; a usability QA annotation might describe how easy it is to learn this function.

Quality attributes have been of interest to the software community at least since the 1970s. There are a variety of published taxonomies and definitions, and many of them have their own research and practitioner communities. From an architect’s perspective, there are three problems with previous discussions of system quality attributes:

1. The definitions provided for an attribute are not testable. It is meaningless to say that a system will be “modifiable.” Every system may be modifiable with respect to one set of changes and not modifiable with respect to another. The other quality attributes are similar in this regard: a system may be robust with respect to some faults and brittle with respect to others. And so forth.

2. Discussion often focuses on which quality a particular concern belongs to. Is a system failure due to a denial-of-service attack an aspect of availability, an aspect of performance, an aspect of security, or an aspect of usability? All four attribute communities would claim ownership of a system failure due to a denial-of-service attack. All are, to some extent, correct. But this doesn’t help us, as architects, understand and create architectural solutions to manage the attributes of concern.

3. Each attribute community has developed its own vocabulary. The performance community has “events” arriving at a system, the security community has “attacks” arriving at a system, the availability community has “failures” of a system, and the usability community has “user input.” All of these may actually refer to the same occurrence, but they are described using different terms.

A solution to the first two of these problems (untestable definitions and overlapping concerns) is to use quality attribute scenarios as a means of characterizing quality attributes (see the next section). A solution to the third problem is to provide a discussion of each attribute—concentrating on its underlying concerns—to illustrate the concepts that are fundamental to that attribute community.

There are two categories of quality attributes on which we focus. The first is those that describe some property of the system at runtime, such as availability, performance, or usability. The second is those that describe some property of the development of the system, such as modifiability or testability.

Within complex systems, quality attributes can never be achieved in isolation. The achievement of any one will have an effect, sometimes positive and sometimes negative, on the achievement of others. For example, almost every quality attribute negatively affects performance. Take portability. The main technique for achieving portable software is to isolate system dependencies, which introduces overhead into the system’s execution, typically as process or procedure boundaries, and this hurts performance. Determining the design that satisfies all of the quality attribute requirements is partially a matter of making the appropriate tradeoffs; we discuss design in Chapter 17. Our purpose here is to provide the context for discussing each quality attribute. In particular, we focus on how quality attributes can be specified, what architectural decisions will enable the achievement of particular quality attributes, and what questions about quality attributes will enable the architect to make the correct design decisions.

4.4. Specifying Quality Attribute Requirements

A quality attribute requirement should be unambiguous and testable. We use a common form to specify all quality attribute requirements. This has the advantage of emphasizing the commonalities among all quality attributes. It has the disadvantage of occasionally being a force-fit for some aspects of quality attributes.

Our common form for quality attribute expression has these parts:

• Stimulus. We use the term “stimulus” to describe an event arriving at the system. The stimulus can be an event to the performance community, a user operation to the usability community, or an attack to the security community. We use the same term to describe a motivating action for developmental qualities. Thus, a stimulus for modifiability is a request for a modification; a stimulus for testability is the completion of a phase of development.

• Stimulus source. A stimulus must have a source—it must come from somewhere. The source of the stimulus may affect how it is treated by the system. A request from a trusted user will not undergo the same scrutiny as a request by an untrusted user.

• Response. How the system should respond to the stimulus must also be specified. The response consists of the responsibilities that the system (for runtime qualities) or the developers (for development-time qualities) should perform in response to the stimulus. For example, in a performance scenario, an event arrives (the stimulus) and the system should process that event and generate a response. In a modifiability scenario, a request for a modification arrives (the stimulus) and the developers should implement the modification—without side effects—and then test and deploy the modification.

• Response measure. Determining whether a response is satisfactory—whether the requirement is satisfied—is enabled by providing a response measure. For performance this could be a measure of latency or throughput; for modifiability it could be the labor or wall clock time required to make, test, and deploy the modification.

These four characteristics of a scenario are the heart of our quality attribute specifications. But there are two more characteristics that are important: environment and artifact.

• Environment. The environment of a requirement is the set of circumstances in which the scenario takes place. The environment acts as a qualifier on the stimulus. For example, a request for a modification that arrives after the code has been frozen for a release may be treated differently than one that arrives before the freeze. A failure that is the fifth successive failure of a component may be treated differently than the first failure of that component.

• Artifact. Finally, the artifact is the portion of the system to which the requirement applies. Frequently this is the entire system, but occasionally specific portions of the system may be called out. A failure in a data store may be treated differently than a failure in the metadata store. Modifications to the user interface may have faster response times than modifications to the middleware.

To summarize how we specify quality attribute requirements, we capture them formally as six-part scenarios. While it is common to omit one or more of these six parts, particularly in the early stages of thinking about quality attributes, knowing that all parts are there forces the architect to consider whether each part is relevant.

In summary, here are the six parts:

1. Source of stimulus. This is some entity (a human, a computer system, or any other actuator) that generated the stimulus.

2. Stimulus. The stimulus is a condition that requires a response when it arrives at a system.

3. Environment. The stimulus occurs under certain conditions. The system may be in an overload condition or in normal operation, or some other relevant state. For many systems, “normal” operation can refer to one of a number of modes. For these kinds of systems, the environment should specify in which mode the system is executing.

4. Artifact. Some artifact is stimulated. This may be a collection of systems, the whole system, or some piece or pieces of it.

5. Response. The response is the activity undertaken as the result of the arrival of the stimulus.

6. Response measure. When the response occurs, it should be measurable in some fashion so that the requirement can be tested.

We distinguish general quality attribute scenarios (which we call “general scenarios” for short)—those that are system independent and can, potentially, pertain to any system—from concrete quality attribute scenarios (concrete scenarios)—those that are specific to the particular system under consideration.

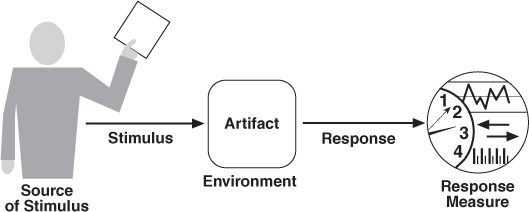

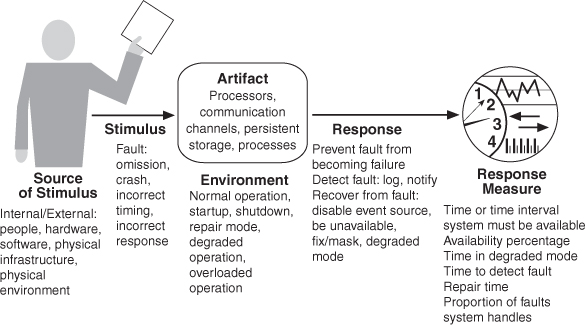

We can characterize quality attributes as a collection of general scenarios. Of course, to translate these generic attribute characterizations into requirements for a particular system, the general scenarios need to be made system specific. Detailed examples of these scenarios will be given in Chapters 5–11. Figure 4.1 shows the parts of a quality attribute scenario that we have just discussed. Figure 4.2 shows an example of a general scenario, in this case for availability.

Figure 4.1. The parts of a quality attribute scenario

Figure 4.2. A general scenario for availability

4.5. Achieving Quality Attributes through Tactics

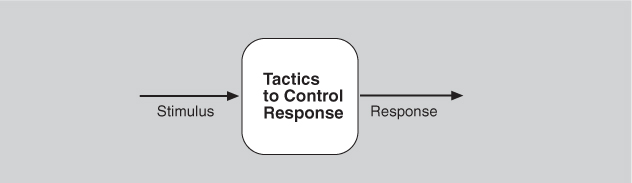

The quality attribute requirements specify the responses of the system that, with a bit of luck and a dose of good planning, realize the goals of the business. We now turn to the techniques an architect can use to achieve the required quality attributes. We call these techniques architectural tactics. A tactic is a design decision that influences the achievement of a quality attribute response—tactics directly affect the system’s response to some stimulus. Tactics impart portability to one design, high performance to another, and integrability to a third.

The focus of a tactic is on a single quality attribute response. Within a tactic, there is no consideration of tradeoffs. Tradeoffs must be explicitly considered and controlled by the designer. In this respect, tactics differ from architectural patterns, where tradeoffs are built into the pattern. (We visit the relation between tactics and patterns in Chapter 14. Chapter 13 explains how sets of tactics for a quality attribute can be constructed, which are the steps we used to produce the set in this book.)

A system design consists of a collection of decisions. Some of these decisions help control the quality attribute responses; others ensure achievement of system functionality. We represent the relationship between stimulus, tactics, and response in Figure 4.3. The tactics, like design patterns, are design techniques that architects have been using for years. Our contribution is to isolate, catalog, and describe them. We are not inventing tactics here, we are just capturing what architects do in practice.

Figure 4.3. Tactics are intended to control responses to stimuli.

Why do we do this? There are three reasons:

1. Design patterns are complex; they typically consist of a bundle of design decisions. But patterns are often difficult to apply as is; architects need to modify and adapt them. By understanding the role of tactics, an architect can more easily assess the options for augmenting an existing pattern to achieve a quality attribute goal.

2. If no pattern exists to realize the architect’s design goal, tactics allow the architect to construct a design fragment from “first principles.” Tactics give the architect insight into the properties of the resulting design fragment.

3. By cataloging tactics, we provide a way of making design more systematic within some limitations. Our list of tactics does not provide a taxonomy. We only provide a categorization. The tactics will overlap, and you frequently will have a choice among multiple tactics to improve a particular quality attribute. The choice of which tactic to use depends on factors such as tradeoffs among other quality attributes and the cost to implement. These considerations transcend the discussion of tactics for particular quality attributes. Chapter 17 provides some techniques for choosing among competing tactics.

The tactics that we present can and should be refined. Consider performance: Schedule resources is a common performance tactic. But this tactic needs to be refined into a specific scheduling strategy, such as shortest-job-first, round-robin, and so forth, for specific purposes. Use an intermediary is a modifiability tactic. But there are multiple types of intermediaries (layers, brokers, and proxies, to name just a few). Thus there are refinements that a designer will employ to make each tactic concrete.

In addition, the application of a tactic depends on the context. Again considering performance: Manage sampling rate is relevant in some real-time systems but not in all real-time systems and certainly not in database systems.

4.6. Guiding Quality Design Decisions

Recall that one can view an architecture as the result of applying a collection of design decisions. What we present here is a systematic categorization of these decisions so that an architect can focus attention on those design dimensions likely to be most troublesome.

The seven categories of design decisions are

1. Allocation of responsibilities

2. Coordination model

3. Data model

4. Management of resources

5. Mapping among architectural elements

6. Binding time decisions

7. Choice of technology

These categories are not the only way to classify architectural design decisions, but they do provide a rational division of concerns. These categories might overlap, but it’s all right if a particular decision exists in two different categories, because the concern of the architect is to ensure that every important decision is considered. Our categorization of decisions is partially based on our definition of software architecture in that many of our categories relate to the definition of structures and the relations among them.

Allocation of Responsibilities

Decisions involving allocation of responsibilities include the following:

• Identifying the important responsibilities, including basic system functions, architectural infrastructure, and satisfaction of quality attributes.

• Determining how these responsibilities are allocated to non-runtime and runtime elements (namely, modules, components, and connectors).

Strategies for making these decisions include functional decomposition, modeling real-world objects, grouping based on the major modes of system operation, or grouping based on similar quality requirements: processing frame rate, security level, or expected changes.

In Chapters 5–11, where we apply these design decision categories to a number of important quality attributes, the checklists we provide for the allocation of responsibilities category is derived systematically from understanding the stimuli and responses listed in the general scenario for that QA.

Coordination Model

Software works by having elements interact with each other through designed mechanisms. These mechanisms are collectively referred to as a coordination model. Decisions about the coordination model include these:

• Identifying the elements of the system that must coordinate, or are prohibited from coordinating.

• Determining the properties of the coordination, such as timeliness, currency, completeness, correctness, and consistency.

• Choosing the communication mechanisms (between systems, between our system and external entities, between elements of our system) that realize those properties. Important properties of the communication mechanisms include stateful versus stateless, synchronous versus asynchronous, guaranteed versus nonguaranteed delivery, and performance-related properties such as throughput and latency.

Data Model

Every system must represent artifacts of system-wide interest—data—in some internal fashion. The collection of those representations and how to interpret them is referred to as the data model. Decisions about the data model include the following:

• Choosing the major data abstractions, their operations, and their properties. This includes determining how the data items are created, initialized, accessed, persisted, manipulated, translated, and destroyed.

• Compiling metadata needed for consistent interpretation of the data.

• Organizing the data. This includes determining whether the data is going to be kept in a relational database, a collection of objects, or both. If both, then the mapping between the two different locations of the data must be determined.

Management of Resources

An architect may need to arbitrate the use of shared resources in the architecture. These include hard resources (e.g., CPU, memory, battery, hardware buffers, system clock, I/O ports) and soft resources (e.g., system locks, software buffers, thread pools, and non-thread-safe code).

Decisions for management of resources include the following:

• Identifying the resources that must be managed and determining the limits for each.

• Determining which system element(s) manage each resource.

• Determining how resources are shared and the arbitration strategies employed when there is contention.

• Determining the impact of saturation on different resources. For example, as a CPU becomes more heavily loaded, performance usually just degrades fairly steadily. On the other hand, when you start to run out of memory, at some point you start paging/swapping intensively and your performance suddenly crashes to a halt.

Mapping among Architectural Elements

An architecture must provide two types of mappings. First, there is mapping between elements in different types of architecture structures—for example, mapping from units of development (modules) to units of execution (threads or processes). Next, there is mapping between software elements and environment elements—for example, mapping from processes to the specific CPUs where these processes will execute.

Useful mappings include these:

• The mapping of modules and runtime elements to each other—that is, the runtime elements that are created from each module; the modules that contain the code for each runtime element.

• The assignment of runtime elements to processors.

• The assignment of items in the data model to data stores.

• The mapping of modules and runtime elements to units of delivery.

Binding Time Decisions

Binding time decisions introduce allowable ranges of variation. This variation can be bound at different times in the software life cycle by different entities—from design time by a developer to runtime by an end user. A binding time decision establishes the scope, the point in the life cycle, and the mechanism for achieving the variation.

The decisions in the other six categories have an associated binding time decision. Examples of such binding time decisions include the following:

• For allocation of responsibilities, you can have build-time selection of modules via a parameterized makefile.

• For choice of coordination model, you can design runtime negotiation of protocols.

• For resource management, you can design a system to accept new peripheral devices plugged in at runtime, after which the system recognizes them and downloads and installs the right drivers automatically.

• For choice of technology, you can build an app store for a smartphone that automatically downloads the version of the app appropriate for the phone of the customer buying the app.

When making binding time decisions, you should consider the costs to implement the decision and the costs to make a modification after you have implemented the decision. For example, if you are considering changing platforms at some time after code time, you can insulate yourself from the effects caused by porting your system to another platform at some cost. Making this decision depends on the costs incurred by having to modify an early binding compared to the costs incurred by implementing the mechanisms involved in the late binding.

Choice of Technology

Every architecture decision must eventually be realized using a specific technology. Sometimes the technology selection is made by others, before the intentional architecture design process begins. In this case, the chosen technology becomes a constraint on decisions in each of our seven categories. In other cases, the architect must choose a suitable technology to realize a decision in every one of the categories.

Choice of technology decisions involve the following:

• Deciding which technologies are available to realize the decisions made in the other categories.

• Determining whether the available tools to support this technology choice (IDEs, simulators, testing tools, etc.) are adequate for development to proceed.

• Determining the extent of internal familiarity as well as the degree of external support available for the technology (such as courses, tutorials, examples, and availability of contractors who can provide expertise in a crunch) and deciding whether this is adequate to proceed.

• Determining the side effects of choosing a technology, such as a required coordination model or constrained resource management opportunities.

• Determining whether a new technology is compatible with the existing technology stack. For example, can the new technology run on top of or alongside the existing technology stack? Can it communicate with the existing technology stack? Can the new technology be monitored and managed?

4.7. Summary

Requirements for a system come in three categories:

1. Functional. These requirements are satisfied by including an appropriate set of responsibilities within the design.

2. Quality attribute. These requirements are satisfied by the structures and behaviors of the architecture.

3. Constraints. A constraint is a design decision that’s already been made.

To express a quality attribute requirement, we use a quality attribute scenario. The parts of the scenario are these:

1. Source of stimulus

2. Stimulus

3. Environment

4. Artifact

5. Response

6. Response measure

An architectural tactic is a design decision that affects a quality attribute response. The focus of a tactic is on a single quality attribute response. Architectural patterns can be seen as “packages” of tactics.

The seven categories of architectural design decisions are these:

1. Allocation of responsibilities

2. Coordination model

3. Data model

4. Management of resources

5. Mapping among architectural elements

6. Binding time decisions

7. Choice of technology

4.8. For Further Reading

Philippe Kruchten [Kruchten 04] provides another categorization of design decisions.

Pena [Pena 87] uses categories of Function/Form/Economy/Time as a way of categorizing design decisions.

Binding time and mechanisms to achieve different types of binding times are discussed in [Bachmann 05].

Taxonomies of quality attributes can be found in [Boehm 78], [McCall 77], and [ISO 11].

Arguments for viewing architecture as essentially independent from function can be found in [Shaw 95].

4.9. Discussion Questions

1. What is the relationship between a use case and a quality attribute scenario? If you wanted to add quality attribute information to a use case, how would you do it?

2. Do you suppose that the set of tactics for a quality attribute is finite or infinite? Why?

3. Discuss the choice of programming language (an example of choice of technology) and its relation to architecture in general, and the design decisions in the other six categories? For instance, how can certain programming languages enable or inhibit the choice of particular coordination models?

4. We will be using the automatic teller machine as an example throughout the chapters on quality attributes. Enumerate the set of responsibilities that an automatic teller machine should support and propose an initial design to accommodate that set of responsibilities. Justify your proposal.

5. Think about the screens that your favorite automatic teller machine uses. What do those screens tell you about binding time decisions reflected in the architecture?

6. Consider the choice between synchronous and asynchronous communication (a choice in the coordination mechanism category). What quality attribute requirements might lead you to choose one over the other?

7. Consider the choice between stateful and stateless communication (a choice in the coordination mechanism category). What quality attribute requirements might lead you to choose one over the other?

8. Most peer-to-peer architecture employs late binding of the topology. What quality attributes does this promote or inhibit?