27. Architectures for the Edge

With Hong-Mei Chen

Human nature is not a machine to be built after a model, and set to do exactly the work prescribed for it, but a tree, which requires to grow and develop itself on all sides, according to the tendency of the inward forces which make it a living thing.

—John Stuart Mill

In this chapter we discuss the place of architecture in edge-dominant systems and discuss how an architect should approach building such systems. An edge-dominant system is one that depends crucially on the inputs of users for its success.

What would Wikipedia be without the encyclopedic entries contributed by users? What would YouTube be without the contributed videos? What would Facebook and Twitter be without their user communities? YouTube serves up approximately 1 billion videos a day. Twitter boasts that its users tweet 50 million times per day. Facebook reports that it serves up about 30 billion pieces of content each month. Flickr recently announced that users had uploaded more than 6 billion photos. Strong, almost maniacal, user participation has elevated each of these sites from fairly routine repositories to forces that shape society.

In each case, the value of these systems comes almost entirely from its users—who happily contribute their opinions and knowledge, their artistic content, their software, and their innovations—and not from some centralized organization. This phenomenon is a cornerstone of the so-called “Web 2.0” movement. Darcy DiNucci, credited with coining the term, wrote in 1999, “The [new] Web will be understood not as screenfuls of text and graphics but as a transport mechanism, the ether through which interactivity happens.” The “old” web was about going to web pages for static information; the “new” web is about participating in the information creation (“crowdsourcing”) and even becoming part of its organization (“folksonomy”).

Many have written about the social, political, and economic consequences of this change, and some see it as nothing short of a revolution along the lines of the industrial revolution. Yochai Benkler’s book The Wealth of Networks—a play on the title of Adam Smith’s classic book The Wealth of Nations, which heralded the start of the industrial revolution—argues that the “radical transformation” of how we create our information environment is restructuring society, particularly our models of production and consumption. Benkler calls this new economic model commons-based peer production. And it’s big: crowdsourced websites that are built on this model have become some of the dominant forces on the web and in society in the past few years. Populist revolutions are catalyzed by Twitter and Facebook. As of the time this book went to press, five of the top ten websites by traffic are peer produced: Facebook, YouTube, Blogger, Wikipedia, and Twitter. And the other five are portals or search engines that pore through the content created by billions of worldwide users. Websites that actually sell something from a centralized organization are rare in the world’s top sites; Amazon.com is the only example, and it’s no accident that it’s the bookseller that derives much of its popularity from the value created by customers.

Along with this paradigm shift, much of the world’s software is now open source. The two most popular web browsers in the world are open source (Mozilla Firefox and Google Chrome). Apache is the most popular web server, currently powering almost two out of every three websites. Open source databases, IDEs, content management systems, and operating systems are all heavy hitters in their respective market spaces.

Why study this in a book about architecture? First, commons-based peer-produced systems are an excellent example of the architecture influence cycle. Second, the architecture of such systems has some important differences from the architectures that you would build for traditional systems. We start by examining how the forces of commons-based peer production change the very nature of the system’s development life cycle.

27.1. The Ecosystem of Edge-Dominant Systems

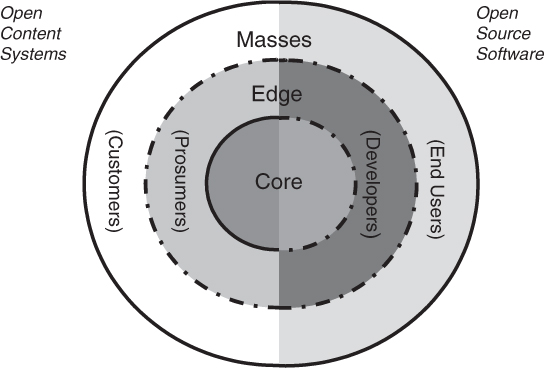

All successful edge-dominant systems, and the organizations that develop and use these systems, share a common ecosystem structure, as shown in Figure 27.1. This is called a “Metropolis” structure, by analogy with a city.

The Metropolis structure is not an architecture diagram: it is a representation of three communities of stakeholders:

Figure 27.1. The Metropolis structure of an edge-dominant system

• Customers and end users, who consume the value produced by the Metropolis

• Developers, who write software and key content for the Metropolis

• Prosumers, who consume content but also produce it

The Metropolis structure also presents three realms of roles and infrastructure:

• In the outermost ring reside the masses of end users of such systems. They contribute requirements but not content.

• The middle ring contains developers and prosumers. These are the stakeholders at the edge whose actions and whose value creation the organization would like to facilitate.

• All of this is held together by the core. The core is software; it provides its services through a set of APIs upon which the periphery can build. Linux’s kernel, Apache’s core, Wikipedia’s wiki, Facebook’s application platform, or the application platforms of the iPhone or Android.

In the Metropolis structure, the realms have different “permeability,” which the figure indicates by the dashed and solid lines.

In open source systems (such as Linux, MySQL, Apache, Eclipse, and Firefox), it is possible to move from the role of an end user to a developer to a core architect, by consistently contributing and moving up in the meritocracy. However, in open content systems (such as Wikipedia, Twitter, YouTube, Slashdot, and Facebook), nobody will invite you to become a software developer for the core, no matter how many cool movies or blog entries you contribute.

Thus, a key question for an organization wishing to foster edge-dominant systems: How should we architect the core and what development principles should we embrace for the periphery/edge?

27.2. Changes to the Software Development Life Cycle

All our familiar software development life cycles—waterfall, Agile, iterative, or prototyping-based—are broken in an edge-dominant, crowdsourced world. These models all assume that requirements can be known; software is developed, tested, and released in planned increments; projects have dedicated finite resources; and management can “manage” these resources. None of these conditions is true in the Metropolis. Let us consider each aspect in turn:

• Requirements can be known. In edge-dominant systems, requirements emerge from its individuals, operating independently. Requirements are never knowable in any global sense and they will inevitably conflict, just as the requirements of a city’s inhabitants often conflict (some want better highways, some want more park land).

• Software is developed, tested, and released in planned increments. All existing software development models assume that systems evolve in an orderly way, through planned releases. An edge-dominant system, on the other hand, is constantly changing. It doesn’t make sense, for example, to talk about the “latest release” of Wikipedia. Resources are noncentralized and so such a system is never “stable.” One cannot conceive of its functionality in terms of “releases” any more than a city has a release; parts are being created, modified, and torn down at all times.

• Projects have dedicated finite resources. Edge-dominant projects are “staffed” by members who are not employed by the project. Such projects are subject to the whims of the members who are not required and cannot be compelled to contribute anything. However, successful projects tend to attract large numbers of contributors. Unlike traditional projects, which have finite resources, typically limited by budgetary constraints, there is no natural limit to the resources available to an edge-dominant project. And these large numbers tend to ameliorate the (unreliable) actions of any individual contributor.

• Management can “manage” these resources. In edge-dominant systems, the developers are often volunteers. They participate in decentralized production processes with no identifiable managers. Linus Torvalds, the creator of the Linux operating system, has noted that he has no authority to order anyone to do anything; he can only attempt to lead and persuade, in the hope that others will follow. Teams in this world are often diverse with differing, sometimes irreconcilable, views.

For edge-dominant systems, the old rules and tools of software development won’t work. Such projects are, to varying degrees, community driven and decentralized with little overall control, as is the case with the major social networking communities (e.g., Twitter, Google+, Facebook), and open content systems (e.g., Wikipedia, YouTube), especially coupled with open source software development.

27.3. Implications for Architecture

The Metropolis structure presented in the previous section, while not an architecture, has important implications for architecture. The key architectural choice for an edge-dominant system is the distinction between core and edge. That is, the architecture of successful edge-dominant systems is, without fail, bifurcated into

• a core (or kernel) infrastructure and

• a set of peripheral functions or services that are built on the core.

This constitutes an architectural pattern very reminiscent of layering. Linux, Firefox, and Apache—to name just a few—are based upon this architectural pattern. Linux applies this pattern twice: at the outermost level the core is the entire Linux kernel, and individual applications, libraries, resources, and auxiliaries act as extensions to the kernel’s functionality—the periphery. Digging into the Linux kernel, we can once again discern a core/periphery pattern. Inside the Linux kernel, modules are defined to enable parallel development of different subsystems. The different functions that one expects to find in an operating system kernel are all present, but they are designed to be separate modules. For instance, there are modules for processor/cache control, memory management, resource management, file system interfacing, networking stacks, device I/O, security, and so forth. All of these modules interact, but they are clearly identifiable, separate modules within the kernel.

We have said many times in this book that architectures come from business goals, as interpreted through the lens of architecturally significant requirements. But what are the business goals for an edge-dominant system? We said earlier that you cannot “know” the requirements for such a system, in any complete sense. Well, this was perhaps a bit hasty.

Requirements for such systems are typically bifurcated into core requirements and periphery requirements:

• Core requirements deliver little or no end-user value and focus on quality attributes and tradeoffs—defining the system’s performance, modularity, security, and so forth. These requirements are generally slow to change as they define the major capabilities and qualities of the system.

• Periphery requirements, on the other hand, are unknowable because they are contributed by the peer network. These requirements deliver the majority of the function and end-user value and change relatively rapidly.

Given this structure, the majority of implementation (the periphery) is crowdsourced to the world using their own tools, to their own standards, at their own pace. The implementers of the core, on the other hand, are generally close knit and highly motivated.

This has at least three implications for the core, which the architect will need to address:

• The core needs to be highly modular, and it provides the foundation for the achievement of quality attributes. The core in a successful core/periphery pattern is designed by a small, coherent team. In open source projects, these people are referred to as the “committers.” In Linux, for example, a strong emphasis on modularity has been postulated to account for its enormous growth. This allows for successful contributions of independent enhancements by scores of distributed and unknown-to-each-other programmers. The peripheral services are enabled by and constrained by the kernel, but are otherwise unspecified.

• The core must be highly reliable. Most cores are heavily tested, which means that testability is important. Heavy testing for the core is tractable because the core is typically small—often orders of magnitude smaller than the periphery—highly controlled, and relatively slow to change. If the core cannot be made small, then its components can be made to be as independent of each other as possible, which eases the testing burden.

• The core must be highly robust with respect to errors in its environment. The reliability of the periphery software is entirely in the hands of the periphery community and the masses (end users and customers). The masses are typically recruited as testers (Mozilla claims to have three million), although this testing is often no more than clicking a button that signals a user’s agreement to have bugs and quality information reported back to the project. Given that the core will undoubtedly be supporting flawed periphery components, robustness of the core is a key requirement; quite simply, failures in the periphery must not cause failures of the core. This means that a system employing the core/periphery pattern should create monitoring mechanisms to determine the current state of the system, and control mechanisms so that bugs in the periphery cannot undermine the core.

The core (often called a platform) is usually implemented as a set of services; complex platforms have hundreds. The Amazon EC2 cloud, for example, has over 110 different APIs documented, and EC2 is only a portion of the Amazon platform. To make these services available to peripheral developers, a number of conditions must hold:

• Documentation must be available for each API, it must be well written, it must be well organized, and it must be up to date. Because a peripheral developer is frequently a volunteer, incomplete, out of date, or unclear documentation presents a barrier to entry. Even if there is a financial motivation (such as from developing an iPhone or Android application), the documentation still must not present a barrier.

• There must be a discovery service. Having hundreds of services means that some of them are going to be redundant and others are going to be unavailable. A discovery service becomes a necessity to enable navigation and flexibility in such a world. A discovery service, in turn, implies a registration service. Services must proactively register upon initialization and be removed if they are no longer active.

• Error detection becomes extremely complicated. If you as a peripheral developer encounter a bug in a service, it may be a bug in the service you are invoking, it may be a bug in a service invoked by the service you are invoking, or anywhere in the chain of services. Reporting a problem and getting it resolved may end up being extremely time-consuming. Quality assurance of services requires constant testing of their availability and correctness. The Netflix Simian Army we discussed in Chapter 10 is an example of how quality assurance on a platform might be structured.

• All of the peer services might be potential denial-of-service attackers. Throttling, monitoring, and quotas must be employed to ensure that service requesters receive adequate responses to their requests.

Building a platform to be a core to support peripheral developers is a nontrivial undertaking. Yet having such a core has paid dramatic dividends for companies comprising the Who’s Who of today’s web.

27.4. Implications of the Metropolis Model

The Metropolis model, as we’ve seen, is paired with the core/periphery pattern for architecture for edge-dominant systems. Adopting this duo brings with it changes to the way that software is developed; in effect, it implies a software development model, with its implications on tools, processes, activities, roles, and expectations. Many such models have evolved over the years, each with its own characteristics, strengths, and weaknesses. Clearly, no one model is best for all projects. For instance, Agile methods are best in projects with rapidly evolving requirements and short time-to-market constraints, whereas a waterfall model is best for large projects with well-understood and stable requirements and complex organizational structures.

The Metropolis model requires a new perspective on system development, resulting in several important changes to how we must create systems:

1. Indifference to phases. The Metropolis model uses the metaphor of a bull’s eye, as opposed to a waterfall, a spiral, a “V,” or other representations that previous models have adopted. The contrast to these previous models is salient: the “phases” of development disappear in the bull’s eye. Instead, we must focus managerial attention on the explicit inclusion of customers (the periphery and the masses) for system development.

2. Crowd management. Policies for crowd management must be aligned with the organization’s strategic goals and must be established early. Crowds are good for certain tasks, but not for all. This implies that business models must be examined to consider policies and associated system development tasks for crowd engagement, performance management monitoring, community protection, and so on. As crowdsourcing is rooted in the “gift” culture, for-profit organizations must carefully align tasks with the volunteers’ values and intentions.

3. Core versus periphery. The Metropolis model differentiates the core and periphery communities, with different tools, processes, activities, roles, and expectations for each. The core must be small and tightly controlled by a group who focus on modularity, core services, and core quality attributes; this enables the unbridled and uncoordinated growth at the periphery.

4. Requirements process. The requirements for a Metropolis system are primarily asserted by the periphery, not elicited from the masses; they emerge from the collective experiences of the community of the periphery, typically through their emails, wikis, and discussion forums. So such forums must be made available—typically provided by members of the core—and the periphery should be encouraged to participate in discussions about the requirements, in effect, to create a community. This changes the fundamental nature of requirements engineering, which has traditionally focused on collecting requirements, making them complete and consistent, and removing redundancies wherever possible.

5. Focus on architecture. The core architecture is the fabric that holds together a Metropolis system. As such, it must be consciously designed to accommodate the specific characteristics of open content and open source systems. For this reason, the architecture cannot “emerge,” as it often does in traditional life-cycle models, and in Agile models. It must be designed up front, built by a small, experienced, motivated team who focus on (1) modularity, to enable the parallel activities of the periphery, and (2) the core quality attributes (security, performance, availability, and so on). There should be a lead architect, or a small team of leads, who can manage project coordination and who have the final say in matters affecting the core. Linus Torvalds, for example, still exerts “veto” rights on matters affecting Linux’s kernel. Virtually every open source project distinguishes between the roles of contributor (who can contribute patches) and committer (who chooses which patches make it into any given release).

6. Distributed testing. The core/periphery distinction also provides guidance for testing activities. The core must be heavily tested and validated, because it is the fabric that holds the system together. Thus, when planning a Metropolis project, it is important to focus on validation of the core and to put tools, guidelines, and processes in place to facilitate this. For example, the core should be kept small; the project should have frequent (perhaps nightly) builds and frequent releases; bug reporting should be built in to the system and require little effort on the part of the periphery. The project must explicitly take advantage of the “many eyes” provided by the periphery.

7. Automated delivery. Delivery mechanisms must be created that work in a distributed, asynchronous manner. These mechanisms must be flexible enough to accept incompleteness of the installed base as the norm. Thus, any delivery mechanism must be tolerant of older versions, multiple coexisting versions, or even incomplete versions. A Metropolis system should also, as far as possible, be tolerant of incompatibilities both within the system and between systems. For example, modern web browsers will still parse old versions of HTML or interact with old versions of web servers; browser add-ons and plug-ins coexist at different version levels and no combination of them will “break” the browser.

8. Management of the periphery. One important aspect of the core/periphery model is that the core exercises very little control over the periphery. Yet this does not mean that the periphery is totally unmanaged. If we examine the extant platforms that are either crowdsourced or peripheral developer sourced, we see that there is always a governance policy set by a managing organization. The Internet and the World Wide Web have a collection of governing boards, large open source projects and Wikipedia are managed by foundations and meritocracies, and private companies such as Facebook or Apple have their own management structures. The governance policies created by the management organizations are enforced in either a proactive or reactive fashion. Some policies are enforced by a combination of both:

• Proactive enforcement. Proactive enforcement inhibits contributions by the prosumers or the peripheral developers unless they meet certain criteria. Within the Internet, for example, IP addresses are assigned. One cannot make up one’s own IP address. Communication protocols and web standards are defined by groups chartered by one of the Internet or web governing organizations. Apple, as another example, screens applications before they are eligible for inclusion in the App Store. And every platform has a collection of APIs that also constrain and govern how a peripheral application interacts with it.

• Reactive enforcement. Reactive enforcement dictates the response in case there is a violation of the organization’s policy. Wikipedia has a collection of editors who are responsible for ensuring the quality of contributions after they have been made. Facebook, YouTube, Flickr and most other crowdsourced sites have procedures to report violations. And if a peripheral developer does not adhere to a protocol or a set of APIs, then their product is flawed in some fashion and the market will likely punish them.

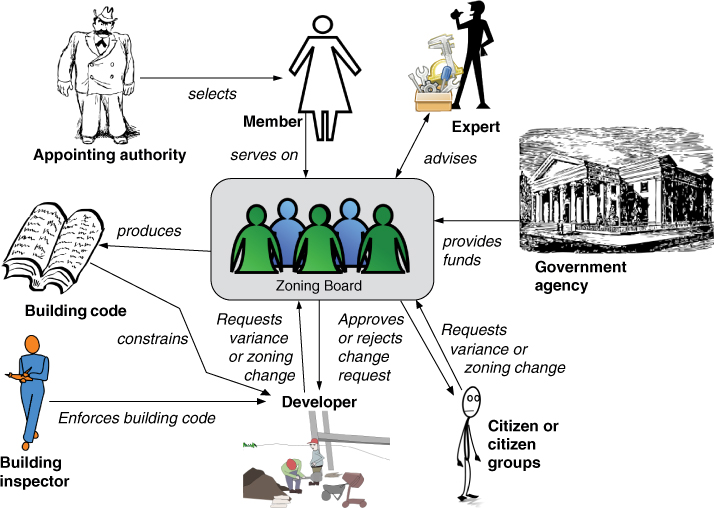

The analogy of a city to explain some of the facets of the core/periphery model can be extended. Zoning is a policy that describes permissible land use for a city or other governmental organization. It specifies, for example, that certain pieces of land are for residential use and other pieces are for industrial use. Zoning policies have both proactive and reactive enforcement. Figure 27.2 shows some of the actors associated with a zoning board. The zoning board is the governance organization; it produces a building code that prescribes legitimate uses and restrictions on various buildings. The building inspector is a reactive enforcer who is responsible for verifying that the buildings conform to permissible standards and usage. As with any analogy, the zoning board is not an exact description of the core/periphery, but it does identify many of the elements that go into controlling contributions.

Figure 27.2. Zoning board stakeholders

Life-cycle models are never revolutionary; they arise in reaction to ambient conditions in the software development world. The Waterfall model was created to focus more attention on removing flaws early in a project’s life cycle, in reaction to the delays, bugs, and failures of projects of ever-increasing complexity. The spiral model and, later, the Rational Unified Process were created because projects needed to produce working versions of software more quickly and to mitigate risks earlier in the software development life cycle. Agile methods grew out of the desire for less bureaucracy, more responsiveness to customer needs, and shorter times to market.

Similarly, the Metropolis model is formally capturing a market response that is already occurring: the rise of commons-based peer production and service-dominant logic. Prior life-cycle models are simply inadequate—mostly mute—on the concerns of edge-dominant systems: crowdsourcing, emergent requirements, and change as a constant. This model offers new ways to think about how a new breed of systems can be developed; its principles help management shift to new project management styles and architecture models that take advantage of the “wisdom of crowds.”

Metropolis model concepts are not appropriate for all forms of development. Smaller systems with limited scope will continue to benefit from the conceptual integrity that accompanies a small, cohesive team. High-security and safety-critical systems, and systems that are built around protected intellectual property, will continue to be built in traditional ways for the foreseeable future. But more and more crowdsourcing, mashups, open source, and other forms of edge-dominant development are being harnessed for value cocreation, and the Metropolis model does speak to this.

27.5. Summary

An edge-dominant system is one that depends crucially on the inputs of users for its success. Users participate in information creation (“crowdsourcing”) and even its organization (“folksonomy”). These systems, part of the “Web 2.0” movement, are having profound social, political, and economic consequences.

All successful edge-dominant systems, and the organizations that develop and use these systems, share a common ecosystem structure known as the “Metropolis” structure. This structure shows how customers, end users, developers, and “prosumers” are related.

Edge systems bring a new life-cycle model to the fore, in which requirements are not completely known, software developed in planned increments is replaced by software that is constantly changing, and projects are staffed by members outside the purview of the central developing organization.

The dominant pattern for edge systems is the core/periphery pattern. This pattern divides the world into a closely controlled core and a loosely controlled periphery. To work, the core needs to be highly modular, highly reliable, and highly robust with respect to external faults. Cores are often designed as a set of services with well-documented APIs, discovery and registration, and sophisticated error detection and reporting.

27.6. For Further Reading

An interesting interview of Linus Torvalds, showing his management style—what he calls “shepherding”—appeared in BusinessWeek magazine several years ago [Hamm 04].

Yochai Benkler’s intriguing book The Wealth of Networks [Benkler 07] puts forth a powerful premise: that the networked information economy is transforming society. It shows how the modern networked economy transforms methods of production and consumption, and creates new forms of value that do not depend on market strategies.

For more information and background on the Metropolis model, you can read the original paper describing it [Kazman 09].

Much of the inspiration for the Metropolis model comes from the Ultra-Large-Scale Systems report [Feiler 06].

MacCormack and colleagues have written extensively on the architecture and properties of what they call “core/periphery” systems. See, for example, [MacCormack 10].

27.7. Discussion Questions

1. Draw the architecture influence cycle for Web 2.0 software systems in general, and for one of its flagship examples (such as Twitter or Facebook).

2. Create a complete pattern description for the core/periphery pattern, modeled on those in Chapter 13.

3. How might the role of architecture documentation be different for an edge-dominant system?

4. Which architectural views would you expect to be the most important to document for a system built under the Metropolis model?

5. How would you establish the architecturally significant requirements for the core? Would you use a Quality Attribute Workshop, or would you use something less structured and more open? Why?

6. Metropolis systems are frequently open source. Some organizations that might want to contribute to or build on top of such a system may balk at releasing all of their code to the public. What architectural means might you employ to address this situation?

7. Choose your favorite crowdsourced system. Write a testability scenario for this system, and choose a set of testability tactics that you would use for it.

8. Constructing and releasing an application on a platform such as the iPhone or the Android requires the developer to adhere to certain specifications and to pass through certain hoops. Redraw Figure 27.2 to reflect the Apple iPhone ecosystem and the Android ecosystem.

9. Find a study that discusses the motivation of Wikipedia contributors. Find another study that discusses the motivation of open source developers. Compare the results of these two studies.