22. Management and Governance

How does a project get to be a year behind schedule? One day at a time.

—Fred Brooks

In this chapter we deal with those aspects of project management and governance that are important for an architect to know. The project manager is the person with whom you, as the architect, must work most closely, from an organizational perspective, and consequently it is important for you to have an understanding of the project manager’s problems and the techniques available to solve those problems. We will deal with project management from the perspectives of planning, organizing, implementing, and measuring. We will also discuss various governance issues associated with architecture.

In this chapter, we advocate a middleweight approach to architecture. It has the following aspects:

• Design the software architecture

• Use the architecture to develop realistic schedules

• Use incremental development to get to market quickly

Architecture is most useful in medium- to large-scale projects—projects that typically have multiple teams, too much complexity for any individual to fully comprehend, substantial investment, and multiyear duration. For such projects the teams need to coordinate, quality attribute problems are not easily corrected, and management demands both short time to market and adequate oversight. Lightweight management methods do not provide for a framework to guide team coordination and frequently require extensive restructuring to repair quality attribute problems. Heavyweight management is usually associated with heavy oversight and a great emphasis on contractual commitments. In some contexts, this is unavoidable, but it has an inherent overhead that slows down development.

22.1. Planning

The planning for a project proceeds over time. There is an initial plan that is necessarily top-down to convince upper management to build this system and give them some idea of the cost and schedule. This top-down schedule is inherently going to be incorrect, possibly by large amounts. It does, however, enable the project manager to educate upper managers as to different elements necessary in software development. According to Dan Paulish, based on his experience at Siemens Corporation, some rules of thumb that can be used to estimate the top-down schedule for medium-sized (~150 KSLOC) projects are these:

• Number of components to be estimated: ~150

• Paper design time per component: ~4 hours

• Time between engineering releases: ~8 weeks

• Overall project development allocation:

• 40 percent design: 5 percent architectural, 35 percent detailed

• 20 percent coding

• 40 percent testing

Once the system has been given a go-ahead and a budget, the architecture team is formed and produces an initial architecture design. The budget item deserves some further mention. One case is that the budget is for the whole project and includes the schedule as well. We will call this case top-down planning. The second case is that the budget is just for the architecture design phase. In this case, the overall project budget emerges from the architecture design phase. This provides a gate that the team has to pass through and gives the holders of the purse strings a chance to consider whether the value of the project is worth the cost.

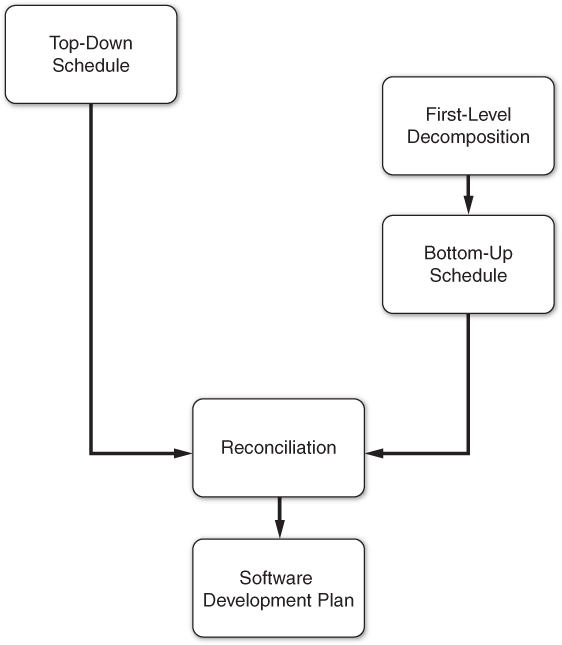

We now describe a merged process that includes both the top-down budget and schedule as well as a bottom-up budget and schedule that emerges from the architecture design phase.

The architecture team produces the initial architecture design and the release plans for the system: what features will be released and when the releases will occur. Once an initial architecture design has been produced, then leads for the various pieces of the project can be assigned and they can build their teams. The definition of the various pieces of the project and their assignment to teams is sometimes called the work breakdown structure. At this point, cost and schedule estimates from the team leads and an overall project schedule can be produced. This bottom-up schedule is usually much more accurate than the top-down schedule, but there may also be significant differences due to differing assumptions. These differences between the top-down and bottom-up schedules need to be discussed and sometimes negotiated. Finally, a software development plan can be written that shows the initial (internal) release as the architectural skeleton with feature-oriented incremental development after that. The features to be in each release are developed in consultation with marketing.

Figure 22.1 shows a process that includes both a top-down schedule and a bottom-up schedule.

Figure 22.1. Overview of planning process

Once the software development plan has been written, the teams can determine times and groups for integration and can define the coordination needs for the various projects. As we will see in the subsection on global development in Section 22.2, the coordination needs for distributed teams can be significant.

22.2. Organizing

Some of the elements of organizing a project are team organization, division of responsibilities between project manager and software architect, and planning for global or distributed development.

Software Development Team Organization

Once the architecture design is in place, it can be used to define the project organization. Each member of the team that designed the software architecture becomes the lead for a team whose responsibility is to implement a portion of the architecture. Thus, responsibility for fleshing out and implementing the design is distributed to those who had a role in its definition.

In addition, many support functions such as writing user documentation, system testing, training, integration, quality assurance, and configuration management are done in a “matrix” form. That is, individuals who are “matrixed” report to one person—a functional manager—for their tasking and professional advancement and to another individual (or to several individuals)—project managers—for their project responsibilities. Matrix organizations have the advantage of being able to allocate and balance resources as needed rather than assign them permanently to a project that may have sporadic needs for individuals with particular skills. They have the disadvantage that the people in them tend to work on several projects simultaneously. This can cause problems such as divided loyalties or competition among projects for resources.

Typical roles within a software development team are the following:

• Team leader—manages tasks within the team.

• Developer—designs and implements subsystem code.

• Configuration manager—performs regular builds and integration tests. This role can frequently be shared among multiple software development teams.

• System test manager—system test and acceptance testing.

• Product manager—represents marketing; defines feature sets and how system being developed integrates with other systems in a product suite.

Division of Responsibilities between Project Manager and Software Architect

One of the important relations within a team is between the software architect and the project manager. You can view the project manager as responsible for the external-facing aspects of the project and the software architect as responsible for the internal aspects of the project. This division will only work if the external view accurately reflects the internal situation and the internal activities accurately reflect the expectations of the external stakeholders. That is, the project manager should know, and reflect to management, the progress and the risks within the project, and the software architect should know, and reflect to developers, stakeholder concerns. The relationship between the project manager and the software architect will have a large impact on the success of a project. They need to have a good working relation and be mindful of the roles they are filling and the boundaries of those roles.

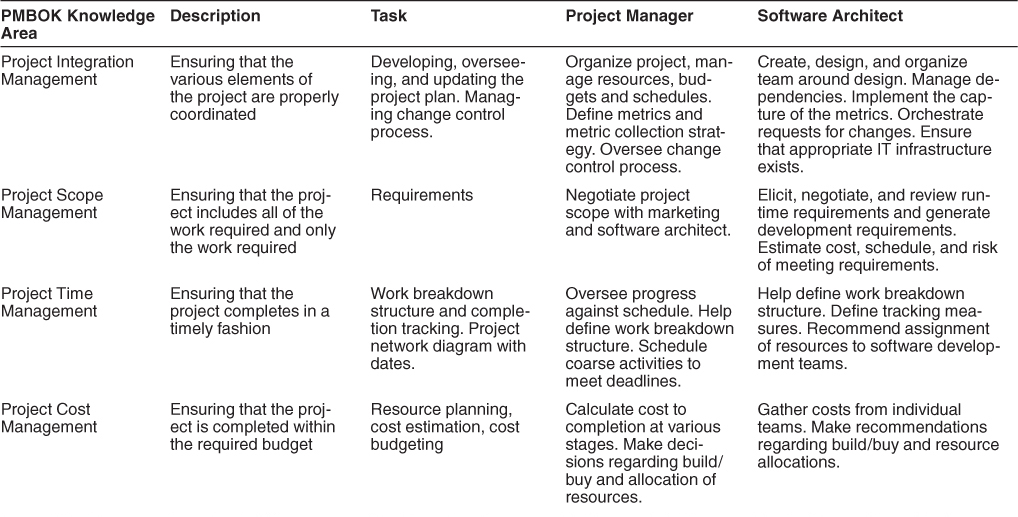

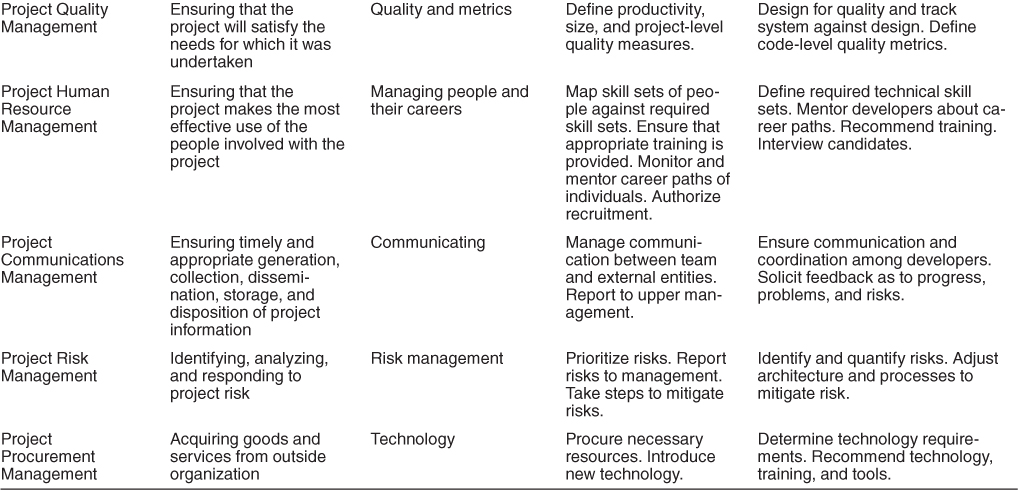

We use the knowledge areas for project management taken from the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) to show the duties of these two roles in a variety of categories. Table 22.1 (on the next page) gives the knowledge area in the language of the PMBOK, defines the knowledge area in English, what that means in software terms, and how the project manager and the software architect collaborate to satisfy that category.

Table 22.1. Division of Responsibilities between Project Manager and Architect

Observe in this table that the project manager is responsible for the business side of the project—providing resources, creating and managing the budget and schedule, negotiating with marketing, ensuring quality—and the software architect is responsible for the technical side of the project—achieving quality, determining measures to be used, reviewing requirements for feasibility, generating develop-time requirements, and leading the development team.

Global Development

Most substantial projects today are developed by distributed teams. In many organizations these teams are globally distributed. Some reasons for this trend are the following:

• Cost. Labor costs vary depending on location, and there is a perception that moving some development to a low-cost venue will decrease the overall cost of the project. Experience has shown that, at least for software development, savings may only be reaped in the long term. Until the developers in the low-cost venue have a sufficient level of domain expertise and until the management practices are adapted to compensate for the difficulties of distributed development, a large amount of rework must be done, thereby cutting into and perhaps overwhelming any savings from wages.

• Skill sets and labor availability. Organizations may not be able to hire developers at a single location: relocation costs are high, the size of the developer pool may be small, or the skill sets needed are specialized and unavailable in a single location. Developing a system in a distributed fashion allows for the work to move to where the workers are rather than forcing the workers to move to the work location.

• Local knowledge of markets. Developers who are developing variants of a system to be sold in their market have more knowledge about the types of features that are assumed and the types of cultural issues that may arise.

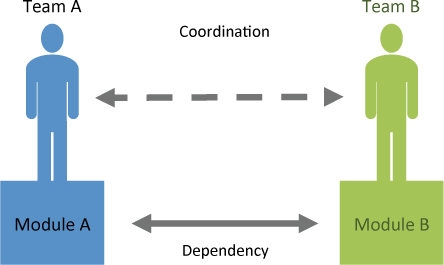

A consequence of performing global or distributed development is that architecture and allocation of responsibilities to teams is more important than in co-located development, where all of the developers are in a single office, or at least in close proximity. For example, assume Module A uses an interface from Module B. In time, as circumstances change, this interface may need to be modified. This means the team responsible for Module B must coordinate with the team responsible for Module A, as indicated in Figure 22.2.

Figure 22.2. If there is a dependency between Module A and Module B, then the teams must coordinate to develop and modify the interface.

Methods for coordination include the following:

• Informal contacts. Informal contacts, such as meeting at the coffee room or in the hallway, are only possible if the teams are co-located.

• Documentation. Documentation, if it is well written, well organized, and properly disseminated, can be used as a means to coordinate the teams, whether co-located or at a distance.

• Meetings. Teams can hold meetings, either scheduled or ad hoc and either face to face or remote, to help bring the team together and raise awareness of issues.

• Electronic communication. Various forms of electronic communication can be used as a coordination mechanism, such as email, news groups, blogs, and wikis.

The choice of method depends on many factors, including infrastructure available, corporate culture, language skills, time zones involved, and the number of teams dependent on a particular module. Until an organization has established a working method for coordinating among distributed teams, misunderstandings among the teams are going to cause delays and, in some cases, serious defects in a project.

22.3. Implementing

During the implementation phase of a project, the project manager and architect have a series of decisions to make. In this section we discuss those involving tradeoffs, incremental development, and managing risk.

Tradeoffs

From the project manager’s perspective, tradeoffs are between quality, schedule, functionality, and cost. These are the aspects of the project that are important to the external stakeholders, and the external stakeholders are the project manager’s constituency. Which of these aspects is most important depends on the project context, and one of the project manager’s major responsibilities is to make this determination.

Over time, there is always new functionality that someone wants to have added to the project. Frequently these requests come from the marketing department. It is important that the consequences of these new requirements, in terms of cost and schedule, be communicated to all concerned stakeholders. This is an area where the project manager and the architect must cooperate. What appear to be small requirements changes from an outsider’s perspective can, at times, require major modifications to the architecture and consequently delay a project significantly.

The project manager’s first response to creeping functionality is to resist it. Acting as a gatekeeper for the project and shielding it from distractions is a portion of the job description. One technique that is frequently used to manage change is a change control board. Bureaucracy can, at times, be your friend. Change control boards are committees set up for the purpose of managing change within a project. The original architecture team members are good candidates to sit on the change control board. Before changing an interface, for example, the impact on those modules that depend on the interface needs to be considered.

Any change to the architecture will incur costs, and it is the architect’s responsibility to be the gatekeeper for such changes. A change in the architecture implies changes in code, changes in the architecture documentation, and perhaps changes in build-time tools that enforce architectural conformance.

Documentation is especially important in distributed development. Co-located teams have a variety of informal coordination possibilities, such as going to the next office or meeting in the coffee room or the hall. Remote teams do not have these informal mechanisms and so must rely on more formal mechanisms such as documentation; team members must have the initiative to talk to each other when doubts arise. One company mounted a webcam on each developer’s desktop to facilitate personal communication.

Incremental Development

Recall that the software development plan lays out the overall schedule. Every six to eight weeks a new release should be available and the specifics of the next release are decided. Forty percent of a typical project’s effort is devoted to testing. This means that testing should begin as soon as possible. Testing for a release can begin once the forward development has begun on the next release. The schedule also has to accommodate repairing the faults uncovered by the testing. This leads to a release being in one of three states:

1. Planning. This occurs toward the end of the prior development release. Enough of the prior release must be completed to understand what will be unfinished in that release and must be carried forward to the next one. At this stage, the software development plan is updated.

2. Development. The planned release is coded. We will discuss below how the project manager and architect track progress on the release. Daily builds and automated testing can give some insight into problems during development.

3. Test and repair. The release is tested through exercise of the test plan. In Chapter 19 we described how the architecture can inform the test plan and even obviate the need for certain types of testing. The problems found during test are repaired or are carried forward to the next release.

Tracking Progress

The project manager can track progress through personal contact with developers (this tends to not scale up well), formal status meetings, metrics, and risk management. Metrics will be discussed in the next section. Personal contact involves checking with key personnel individually to determine progress. These are one-on-one meetings, either scheduled or unscheduled.

Meetings, in general, are either status or working meetings. The two types of meetings should not be mixed. In a status meeting, various teams report on progress. This allows for communication among the teams. Issues raised at status meetings should be resolved outside of these meetings—either by individuals or by separately scheduled working meetings. When an issue is raised at a status meeting, a person should be assigned to be responsible for the resolution of that issue.

Meetings are expensive. Holding effective meetings is an important skill for a manager, whether the project manager or the architect. Meetings should have written agendas that are circulated before the meetings begin, attendees should be expected to have done some prework for the meeting (such as read-ahead), and only essential individuals should attend.

One of the outputs of status meetings is a set of risks. A risk is a potential problem together with the consequences if it occurs. The likelihood of the risk occurring should also be recorded. Risks are also raised at reviews. We have discussed architecture evaluation, and it is important from a project management perspective that reviews are included in the schedule. These can be code reviews, architecture reviews, or requirements reviews. Risks are also raised by developers. They are the ones who have the best perspective on potential problems at the implementation level. Architecture evaluation is also important because it is a source of discovering risks.

The project manager must prioritize the risks, frequently with the assistance of the architect, and, for the most serious risks, develop a mitigation strategy. Mitigating risks is also a cost, and so implementing the strategy to reduce a risk depends on its priority, likelihood of occurrence, and cost if it does occur.

22.4. Measuring

Metrics are an important tool for project managers. They enable the manager to have an objective basis both for their own decision making and for reporting to upper management on the progress of the project.

Metrics can be global—pertaining to the whole project—or they may depend on a particular phase of the project. Another important class of metrics is “cost to complete.” We discuss each of these below.

Global Metrics

Global metrics aid the project manager in obtaining an overall sense of the project and tracking its progress over time. All global metrics should be updated from time to time as the project proceeds.

First, the project manager needs a measure of project size. The three most common measures of project size are lines of code, function points, and size of the test suite. None of these is completely satisfactory as a predictor of cost or effort, but these are the most commonly used size metrics in practice.

Schedule deviation is another global metric. Schedule deviation is measured by taking the difference between the planned work time and the actual work time. Once time has passed, it can never be recovered. If a project falls behind in its schedule, a tradeoff must be made between the aspects we mentioned before: schedule, quality, functionality, and cost. As the project proceeds, schedule deviation indicates a failure of estimation or an unforeseen occurrence. By drilling down in this metric and discovering which teams are slipping, the project manager can decide to reallocate resources, if necessary.

Developer productivity is another metric that the project manager can track. The project manager should look for anomalies in the productivity of the developers. An anomaly indicates a potential problem that should be investigated: perhaps a developer is inadequately trained for a task, or perhaps the task was improperly estimated. Earned value management is one technique for measuring the productivity of developers.

Finally, defects should be tracked. Again, anomalies in the number of defects discovered over time indicate a potential problem that should be investigated. Not only defects but technical debt should be tracked as well (see Chapter 15).

All of these measures have both a historical basis and a project basis. The historical basis is used to make the initial estimates and then the project basis is used for ongoing management activities.

Phase Metrics and Costs to Complete

Open issues should be kept for each phase. For example, until a design is complete, there are always open issues. These should be tracked and additional resources allocated if they are not resolved in a timely fashion. Risks represent open issues that should be tracked, as does the project backlog.

Unmitigated risks from reviews are treated in a similar fashion. We have already discussed risk management, but one item a project manager can report to upper management is the number of high-priority risks and the status of their mitigation.

Costs to complete is a bottom-up measure that derives from the bottom-up schedule. Once the various pieces of the architecture have been assigned to teams, then the teams take ownership of their schedule and the cost to complete their pieces.

22.5. Governance

Up to this point, we have maintained a focus in this chapter. We have focused on the project manager as the embodiment of the project and have not discussed the external forces that act on the project manager. The topic of governance deals directly with these other forces. The Open Group defines architecture governance as “the practice and orientation by which enterprise architectures and other architectures are managed and controlled.” Implicit in this definition is the idea that the project—which is the focus of this book—exists in an organizational context. This context will mediate the interactions of the system being constructed with the other systems in the organization.

The Open Group goes on to identify four items as responsibilities of a governance board:

• Implementing a system of controls over the creation and monitoring of all architectural components and activities, to ensure the effective introduction, implementation, and evolution of architectures within the organization

• Implementing a system to ensure compliance with internal and external standards and regulatory obligations

• Establishing processes that support effective management of the above processes within agreed parameters

• Developing practices that ensure accountability to a clearly identified stakeholder community, both inside and outside the organization

Note the emphasis on processes and practices. Maintaining an effective governance process without excessive overhead is a line that is difficult to maintain for an organization.

The problem comes about because each system that exists in an enterprise has its own stakeholders and its own internal governance processes. Creating a system that utilizes a collection of other systems raises the issue of who is in control.

Consider the following example. Company A has a collection of products that cover different portions of a manufacturing facility. One collection of systems manages the manufacturing process, another manages the processes by which various portions of the end product are integrated, and a third collection manages the enterprise. Each of these collections of systems has its own set of customers.

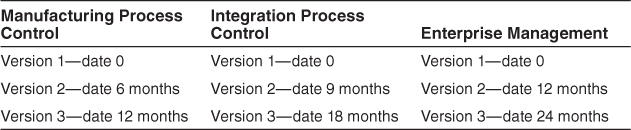

Now suppose that the board of directors wishes to market the collection as an end-to-end solution for a manufacturing facility. It further turns out that the systems that manage the manufacturing process have a 6-month release cycle because the technology is changing quickly in this area. The systems that manage the integration process have a 9-month release cycle because they are based on a widely used commercial product with a 9-month release cycle. The enterprise systems have a 12-month release cycle because they are based on an organization’s fiscal year and reflect tax and regulatory changes that are likely to occur on fiscal year boundaries. Table 22.2 shows these schedules beginning at date 0.

Table 22.2. Release Schedules of Different Types of Products

What should the release schedule be for the combined end-to-end solution? Recall that each of these sets of products has reasons for their release schedule and each has its own set of customers who will not be receptive to changes in the release schedule. This is typical of the sort of problem that a governance committee deals with.

22.6. Summary

A project must be planned, organized, implemented, tracked, and governed.

The plan for a project is initially developed as a top-down schedule with an acknowledgement that it is only an estimate. Once the decomposition of the system has been done, a bottom-up schedule can be developed. The two must be reconciled, and this becomes the basis for the software development plan.

Teams are created based on the software development plan. The software architect and the project manager must coordinate to oversee the implementation. Global development creates a need for an explicit coordination strategy that is based on more formal methods than needed for co-located development.

The implementation itself causes tradeoffs between schedule, function, and cost. Releases are done in an incremental fashion and progress is tracked by both formal metrics and informal communication.

Larger systems require formal governance mechanisms. The issue of who has control over a particular portion of the system may prevent some business goals from being realized.

22.7. For Further Reading

Dan Paulish has written an excellent book on managing in an architecture-centric environment—[Paulish 02]—and much of the material in this chapter is adapted from his book.

The Agile community has independently arrived at a medium-weight management process that advocates up-front architecture. See [Coplein 10] for an example of the Agile community’s description of architecture.

The responsibilities of a governance board can be found in The Open Group Architecture Framework (TOGAF), produced by the Open Group. www.opengroup.org/architecture/togaf8-doc/arch/chap26.html

Basic concepts of project management are covered in [IEEE 11].

Using concepts of lean manufacturing, Kanban is a method for scheduling the production of a system [Ladas 09].

Earned value management is discussed in en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Earned_value_management

22.8. Discussion Questions

1. What are the reasons that top-down and bottom-up schedule estimates differ and how would you resolve this conflict in practice?

2. Generic project management practices advocate creating a work breakdown structure as the first artifact produced by a project. What is wrong with this practice from an architectural perspective?

3. If you were managing a globally distributed team, what architectural documentation artifacts would you want to create first?

4. If you were managing a globally distributed team, what aspects of project management would have to change to account for cultural differences?

5. Enumerate three different global metrics and discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each?

6. How could you use architectural evaluation as a portion of a governance plan?

7. In Chapter 1 we described a work assignment structure for software architecture, which can be documented as a work assignment view. (Because it maps software elements—modules—to a nonsoftware environmental structure—the organizational units that will be responsible for implementing the modules—it is a kind of allocation view.) Discuss how documenting a work assignment view for your architecture provides a vehicle for software architects and managers to work together to staff a project. Where is the dividing line between the part of the work assignment view that the architect should provide and the part that the manager should provide?