15. Architecture in Agile Projects

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change.

—Charles Darwin

Since their first appearance over a decade ago, the various flavors of Agile methods and processes have received increasing attention and adoption by the worldwide software community. New software processes do not just emerge out of thin air; they evolve in response to a palpable need. In this case, the software development world was responding to a need for projects to be more responsive to their stakeholders, to be quicker to develop functionality that users care about, to show more and earlier progress in a project’s life cycle, and to be less burdened by documenting aspects of a project that would inevitably change. Is any of this inimical to the use of architecture? We emphatically say “no.” In fact, the question for a software project is not “Should I do Agile or architecture?”, but rather questions such as “How much architecture should I do up front versus how much should I defer until the project’s requirements have solidified somewhat?”, “When and how should I refactor?”, and “How much of the architecture should I formally document, and when?” We believe that there are good answers to all of these questions, and that Agile and architecture are not just well suited to live together but in fact critical companions for many software projects.

The Agile software movement began to receive considerable public attention approximately a decade ago, with the release of the “Agile Manifesto.” Its roots extend at least a decade earlier than that, in practices such as Extreme Programming and Scrum. The Agile Manifesto, originally signed by 17 developers, was however a brilliant public relations move; it is brief, pithy, and sensible:

The authors of the Manifesto go on to describe the twelve principles that underlie their reasoning:

1. Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.

2. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.

3. Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

4. Business people and developers must work together daily throughout the project.

5. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the environment and support they need, and trust them to get the job done.

6. The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.

7. Working software is the primary measure of progress.

8. Agile processes promote sustainable development. The sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain a constant pace indefinitely.

9. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good design enhances agility.

10. Simplicity—the art of maximizing thev amount of work not done—is essential.

11. The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

12. At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behavior accordingly.

There has been considerable elaboration of the Agile Manifesto, and Agile processes, since its first release, but the basic principles have remained solid. The Agile movement (and its predecessors) have gained considerable attention and have enjoyed widespread adoption over the past two decades. These processes were initially employed on small- to medium-sized projects with short time frames and enjoyed considerable success. They were not often used for larger projects, particularly those with distributed development. This is not surprising, given the twelve principles.

In particular principles 4 and 6 imply the need for co-location or, if co-location is not possible, then at least a high level of communication among the distributed teams. Indeed, one of the core practices of Agile projects is frequent (often daily) face-to-face meetings. Principle 11 says that, for best results, teams should be self-organizing. But self-organization is a social process that is much more cumbersome if those teams are not physically co-located. In this case we believe that the creators of the twelve Agile principles got it wrong. The best teams may be self-organizing, but the best architectures still require much more than this—technical skill, deep experience, and deep knowledge.

Principle 1 argues for “early and continuous delivery of valuable software” and principle 7 claims that “Working software is the primary measure of progress.” One might argue that a focus on early and continuous release of software, where “working” is measured in terms of customer-facing features, leaves little time for addressing the kinds of cross-cutting concerns and infrastructure critical to a high-quality large-scale system.

It has been claimed by some that there is an inherent tension between being agile and doing a conscientious job of architecting. But is there truly a tension? And if so, how do you go about characterizing it and reasoning about it? In short, how much architecture is the “right” amount of architecture?

Our brief answer, in this chapter, is that there is no tension. This issue is not “Agile versus Architecture” but rather “how best to blend Agile and Architecture.”

One more point, before we dive into the details: The Agile Manifesto is itself a compromise: a pronouncement created by a committee. The fact that architecture doesn’t clearly live anywhere within it is most likely because they had no consensus opinion on this topic and not because there is any inherent conflict.

15.1. How Much Architecture?

We often think of the early software development methods that emerged in the 1970s—such as the Waterfall method—as being plan-driven and inflexible. But this inflexibility is not for nothing. Having a strong up-front plan provides for considerable predictability (as long as the requirements don’t change too much) and makes it easier to coordinate large numbers of teams. Can you imagine a large construction or aerospace project without heavy up-front planning? Agile methods and practitioners, on the other hand, often scorn planning, preferring instead teamwork, frequent face-to-face communication, flexibility, and adaptation. This enhances invention and creativity.

Let us consider a specific case, to illustrate the tradeoff between up-front planning and agility: the Agile technique of employing user stories. User stories are a cornerstone of the Agile approach. Each user story describes a set of features visible to the user. Implementing user stories is a way of demonstrating progress to the customer. This can easily lead to an architecture in which every feature is independently designed and implemented. In such an environment, concerns that cut across more than one feature become hard to capture. For example, suppose there is a utility function that supports multiple features. To identify this utility function, coordination is required among the teams that develop the different features, and it also requires a role in which a broad overview across all of the features is maintained. If the development team is geographically distributed and the system being developed is a large one, then emphasis on delivering features early will cause massive coordination problems. In an architecture-centric project, a layered architecture is a way to solve this problem, with features on upper layers using shared functionality of the lower layers, but that requires up-front planning and design and feature analysis.

Successful projects clearly need a successful blend of the two approaches. For the vast majority of nontrivial projects, this is not and never should be an either/or choice. Too much up-front planning and commitment can stifle creativity and the ability to adapt to changing requirements. Too much agility can be chaos. No one would want to fly in an aircraft where the flight control software had not been rigorously planned and thoroughly analyzed. Similarly, no one would want to spend 18 months planning an e-commerce website for their latest cell-phone model, or video game, or lipstick (all of which are guaranteed to be badly out of fashion in 18 months). What we all want is the sweet spot—what George Fairbanks calls “just enough architecture.” This is not just a matter of doing the right amount of architecture work, but also doing it at the right time. Agile projects tend to want to evolve the architecture, as needed, in real time, whereas large software projects have traditionally favored considerable up-front analysis and planning.

The whole point of choosing how much time to budget for architecture is to reduce risk. Risk may be financial, political, operational, or reputational. Some risks might involve human life or the chance of legal action. Chapter 22 covers risk management and budgets for planning in the context of architecture.

15.2. Agility and Architecture Methods

Throughout this book we emphasize methods for architecture design, analysis, and documentation. We unabashedly like methods! And so does the Agile community: dozens of books have been written on Scrum, Extreme Programming, Crystal Clear, and other Agile methods. But how should we think of architecture-centric techniques and methods in an Agile context? How well do they fit with the twelve Agile principles, for example?

We believe that they fit very well. The methods we present are based on the essential elements needed to perform the activity. If you believe that architecture needs to be designed, analyzed, and documented, then the techniques we present are essential regardless of the project in which they are embedded. The methods we present are essentially driven by the motivation to reduce risk, and by considerations of costs and benefits.

Among all of our methods—for extracting architecturally significant requirements, for architecture design, for architecture evaluation, for architecture documentation—that you’ll see in subsequent chapters, one might expect the greatest Agile friction from evaluation and documentation. And so the rest of this section will examine those two practices in an Agile context.

Architecture Documentation and YAGNI

Our approach to architecture documentation is called Views and Beyond, and it will be discussed in Chapter 18. Views and Beyond and Agile agree emphatically on the following point: If information isn’t needed, don’t spend the resources to document it. All documentation should have an intended use and audience in mind, and be produced in a way that serves both.

One of our fundamental principles of technical documentation is “Write for the reader.” That means understanding who will read the documentation and how they will use it. If there is no audience, there is no need to produce the documentation. This principle is so important in Agile methods that it has been given its own name: YAGNI. YAGNI means “you ain’t gonna need it,” and it refers to the idea that you should only implement or document something when you actually have the need for it. Do not spend time attempting to anticipate all possible needs.

The Views and Beyond approach uses the architectural view as the “unit” of documentation to be produced. Selecting the views to document is an example of applying this principle. The Views and Beyond approach prescribes producing a view if and only if it addresses substantial concerns of an important stakeholder community. And because documentation is not a monolithic activity that holds up all other progress until it is complete, the view selection method prescribes producing the documentation in prioritized stages to satisfy the needs of the stakeholders who need it now.

We document the portions of the architecture that we need to teach to newcomers, that embody significant potential risks if not properly managed, and that we need to change frequently. We document what we need to convey to readers so they can do their job. Although “classic” Agile emphasizes documenting the minimum amount needed to let the current team of developers make progress, our approach emphasizes that the reader might be a maintainer assigned to make a technology upgrade years after the original development team has disbanded.

Architecture Evaluation

Could an architecture evaluation work as part of an Agile process? Absolutely. In fact, doing so is perfectly Agile-consistent, because meeting stakeholders’ important concerns is a cornerstone of Agile philosophy.

Our approach to architecture evaluation is exemplified by the Architecture Tradeoff Analysis Method (ATAM) of Chapter 21. It does not endeavor to analyze all, or even most, of an architecture. Rather, the focus is determined by a set of quality attribute scenarios that represent the most important (but by no means all) of the concerns of the stakeholders. “Most important” is judged by the amount of value the scenario brings to the architecture’s stakeholders, or the amount of risk present in achieving the scenario. Once these scenarios have been elicited, validated, and prioritized, they give us an evaluation agenda based on what is important to the success of the system, and what poses the greatest risk for the system’s success. Then we only delve into those areas that pose high risk for the achievement of the system’s main functions and qualities.

And as we will see in Chapter 21, it is easy to tailor a lightweight architecture evaluation, for quicker and less-costly analysis and feedback whenever in the project it is called for.

15.3. A Brief Example of Agile Architecting

Our claim is that architecture and agility are quite compatible. Now we will look at a brief case study of just that. This project, which one of the authors worked on, involved the creation and evolution of a web-conferencing system. Throughout this project we practiced “agile architecting” and, we believe, hit the sweet spot between up-front planning where possible, and agility where needed.

Web-conferencing systems are complex and demanding systems. They must provide real-time responsiveness, competitive features, ease of installation and use, lightweight footprint, and much more. For example:

• They must work on a wide variety of hardware and software platforms, the details of which are not under the control of the architect.

• They must be reliable and provide low-latency response times, particularly for real-time functionality such as voice over IP (VoIP) and screen sharing.

• They must provide high security, but do so over an unknown network topology and an unknown set of firewalls and firewall policies.

• They must be easily modified and easily integrated into a wide variety of environments and applications.

• They must be highly usable and easily installed and learned by users with widely varying IT skills.

Many of the above-mentioned goals trade off against each other. Typically security (in the form of encryption) comes at the expense of real-time performance (latency). Modifiability comes at the expense of time-to-market. Availability and performance typically come at the expense of modifiability and cost.

Even if it is possible to collect, analyze, and prioritize all relevant data, functional requirements, and quality attribute requirements, the stringent time-to-market constraints that prevail in a competitive climate such as web-conferencing would have prevented us from doing this. Trying to support all possible uses is intractable, and the users themselves were poorly equipped for envisioning all possible potential uses of the system. So just asking the users what they wanted, in the fashion of a traditional requirements elicitation, was not likely to work.

This results in a classic “agility versus commitment” problem. On the one hand the architect wants to provide new capabilities quickly, and to respond to customer needs rapidly. On the other hand, long-term survival of the system and the company means that it must be designed for extensibility, modifiability, and portability. This can best be achieved by having a simple conceptual model for the architecture, based on a small number of regularly applied patterns and tactics. It was not obvious how we would “evolve” our way to such an architecture. So, how is it possible to find the “sweet spot” between these opposing forces?

The WebArrow web-conferencing system faced precisely this dilemma. It was impossible for the architect and lead designers to do purely top-down architectural design; there were too many considerations to weigh at once, and it was too hard to predict all of the relevant technological challenges. For example, they had cases where they discovered that a vendor-provided API did not work as specified—imagine that!—or that an API exposing a critical function was simply missing. In such cases, these problems rippled through the architecture, and workarounds needed to be fashioned . . . fast!

To address the complexity of this domain, the WebArrow architect and developers found that they needed to think and work in two different modes at the same time:

• Top-down—designing and analyzing architectural structures to meet the demanding quality attribute requirements and tradeoffs

• Bottom-up—analyzing a wide array of implementation-specific and environment-specific constraints and fashioning solutions to them

To compensate for the difficulty in analyzing architectural tradeoffs with any precision, the team adopted an agile architecture discipline combined with a rigorous program of experiments aimed at answering specific tradeoff questions. These experiments are what are called “spikes” in Agile terminology. And these experiments proved to be the key in resolving tradeoffs, by helping to turn unknown architectural parameters into constants or ranges. Here’s how it worked:

1. First, the WebArrow team quickly created and crudely analyzed an initial software and system architecture concept, and then they implemented and fleshed it out incrementally, starting with the most critical functionality that could be shown to a customer.

2. They adapted the architecture and refactored the design and code whenever new requirements popped up or a better understanding of the problem domain emerged.

3. Continuous experimentation, empirical evaluation, and architecture analysis were used to help determine architectural decisions as the product evolved.

For example, incremental improvement in the scalability and fault-tolerance of WebArrow was guided by significant experimentation. The sorts of questions that our experiments (spikes) were designed to answer were these:

• Would moving to a distributed database from local flat files negatively impact feedback time (latency) for users?

• What (if any) scalability improvement would result from using mod_perl versus standard Perl? How difficult would the development and quality assurance effort be to convert to mod_perl?

• How many participants could be hosted by a single meeting server?

• What was the correct ratio between database servers and meeting servers?

Questions like these are difficult to answer analytically. The answers rely on the behavior and interactions of third-party components, and on performance characteristics of software for which no standard analytic models exist. The Web-Arrow team’s approach was to build an extensive testing infrastructure (including both simulation and instrumentation), and to use this infrastructure to compare the performance of each modification to the base system. This allowed the team to determine the effect of each proposed improvement before committing it to the final system.

The lesson here is that making architecture processes agile does not require a radical re-invention of either Agile practices or architecture methods. The Web-Arrow team’s emphasis on experimentation proved the key factor; it was our way of achieving an agile form of architecture conception, implementation, and evaluation.

This approach meant that the WebArrow architecture development approach was in line with many of the twelve principles, including:

• Principle 1, providing early and continuous delivery of working software

• Principle 2, welcoming changing requirements

• Principle 3, delivering working software frequently

• Principle 8, promoting sustainable development at a constant pace

• Principle 9, giving continuous attention to technical excellence and good design

15.4. Guidelines for the Agile Architect

Barry Boehm and colleagues have developed the Incremental Commitment Model—a hybrid process model framework that attempts to find the balance between agility and commitment. This model is based upon the following six principles:

1. Commitment and accountability of success-critical stakeholders

2. Stakeholder “satisficing” (meeting an acceptability threshold) based on success-based negotiations and tradeoffs

3. Incremental and evolutionary growth of system definition and stakeholder commitment

4. Iterative system development and definition

5. Interleaved system definition and development allowing early fielding of core capabilities, continual adaptation to change, and timely growth of complex systems without waiting for every requirement and subsystem to be defined

6. Risk management—risk-driven anchor point milestones, which are key to synchronizing and stabilizing all of this concurrent activity

Grady Booch has also provided a set of guidelines for an agile architecture (which in turn imply some duties for the agile architect). Booch claims that all good software-intensive architectures are agile. What does he mean by this? He means that a successful architecture is resilient and loosely coupled. It is composed of a core set of well-reasoned design decisions but still contains some “wiggle room” that allows modifications to be made and refactorings to be done, without ruining the original structure.

Booch also notes that an effective agile process will allow the architecture to grow incrementally as the system is developed and matures. The key to success is to have decomposability, separation of concerns, and near-independence of the parts. (Sound familiar? These are all modifiability tactics.)

Finally, Booch notes that to be agile, the architecture should be visible and self-evident in the code; this means making the design patterns, cross-cutting concerns, and other important decisions obvious, well communicated, and defended. This may, in turn, require documentation. But whatever architectural decisions are made, the architect must make an effort to “socialize” the architecture.

Ward Cunningham has coined the term “technical debt.” Technical debt is an analogy to the normal debt that we acquire as consumers: we purchase something now and (hope to) pay for it later. In software the equivalent of “purchasing something now” is quick-and-dirty implementation. Such implementation frequently leaves technical debt that incurs penalties in the future, in terms of increased maintenance costs. When technical debt becomes unacceptably high, projects need to pay down some of this debt, in the form of refactoring, which is a key part of every agile architecting process.

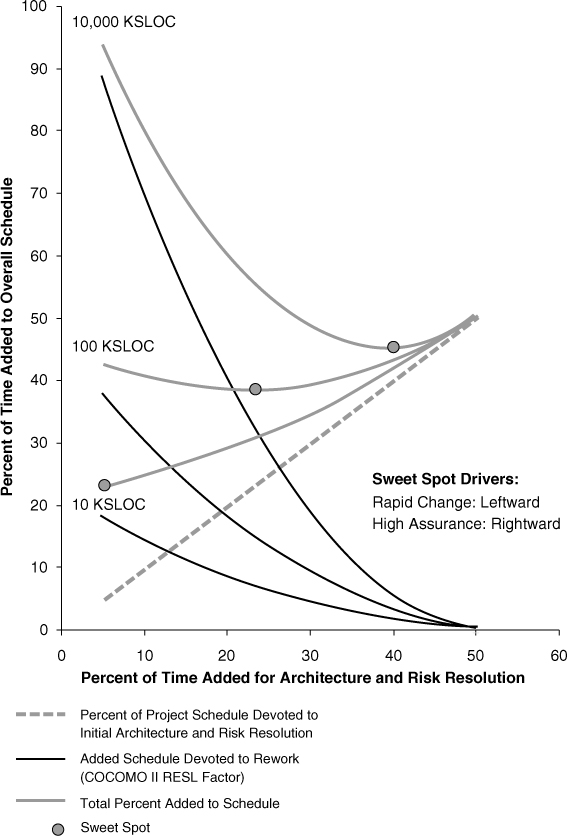

1. If you are building a large and complex system with relatively stable and well-understood requirements, it is probably optimal to do a large amount of architecture work up front (see Figure 15.1 for some sample values for “large”).

2. On big projects with vague or unstable requirements, start by quickly designing a complete candidate architecture even if it is just a “PowerPoint architecture,” even if it leaves out many details, and even if you design it in just a couple of days. Alistair Cockburn has introduced a similar idea in his Crystal Clear method, called a “walking skeleton,” which is enough architecture to be able to demonstrate end-to-end functionality, linking together the major system functions. Be prepared to change and elaborate this architecture as circumstances dictate, as you perform your spikes and experiments, and as functional and quality attribute requirements emerge and solidify. This early architecture will help guide development, help with early problem understanding and analysis, help in requirements elicitation, help teams coordinate, and help in the creation of coding templates and other project standards.

3. On smaller projects with uncertain requirements, at least try to get agreement on the central patterns to be employed, but don’t spend too much time on construction, documentation, or analysis up front. In Chapter 21 we will show how analysis can be done in a relatively lightweight and “just-in-time” fashion.

15.5. Summary

The Agile software movement is emblemized by the Agile Manifesto and a set of principles that assign high value to close-knit teams and continuous and frequent delivery of working software. Agile processes were initially employed on small- to medium-sized projects with short time frames and enjoyed considerable success. They were not often used for larger projects, particularly those with distributed development.

Although there might appear to be an inherent tension between being agile and architecture practices of the sort prescribed in this book, the underlying philosophies are not at odds and can be married to great effect. Successful projects need a successful blend of the two approaches. Too much up-front planning and commitment can be stifling and unresponsive to customers’ needs, whereas too much agility can simply result in chaos. Agile architects tend to take a middle ground, proposing an initial architecture and running with that, until its technical debt becomes too great, at which point they need to refactor.

Boehm and Turner, analyzing historical data from 161 industrial projects, examined the effects of up-front architecture and risk resolution effort. They found that projects tend to have a “sweet spot” where some up-front architecture planning pays off and is not wasteful.

Among this book’s architecture methods, documentation and evaluation might seem to be where the most friction with Agile philosophies might lie. However, our approaches to these activities are risk-based and embodied in methods that help you focus effort where it will most pay off.

The WebArrow example showed how adding experimentation to the project’s processes enabled it to obtain benefits from both architecture and classic Agile practices, and be responsive to ever-changing requirements and domain understanding.

15.6. For Further Reading

Agile comes in many flavors. Here are some of the better-known ones:

• Extreme Programming [Beck 04]

• Scrum [Schwaber 04]

• Feature-Driven Development [Palmer 02]

• Crystal Clear [Cockburn 04]

The journal IEEE Software devoted an entire special issue in 2010 to the topic of agility and architecture. The editor’s introduction [Abrahamsson 10] discusses many of the issues that we have raised here.

George Fairbanks in his book Just Enough Architecture [Fairbanks 10] provides techniques that are very compatible with Agile methods.

Barry Boehm and Richard Turner [Boehm 04] offer a data- and analysis-driven perspective on the risks and tradeoffs involved in the continuum of choices regarding agility and what they called “discipline.” The choice of “agility versus discipline” in the title of the book has angered and alienated many practitioners of Agile methods, most of which are quite disciplined. While this book does not focus specifically on architecture, it does touch on the subject in many ways. This work was expanded upon in 2010, when Boehm, Lane, Koolmanojwong, and Turner described the Incremental Commitment Model and its relationship to agility and architecture [Boehm 10]. All of Boehm and colleagues’ work is informed by an active attention to risk. The seminal article on software risk management [Boehm 91] was written by Barry Boehm, more than 20 years ago, and it is still relevant and compelling reading today.

Carriere, Kazman, and Ozkaya [Carriere 10] provide a way to reason about when and where in an architecture you should do refactoring—to reduce technical debt—based on an analysis of the propagation cost of anticipated changes.

The article by Graham, Kazman, and Walmsley [Graham 07] provides substantially more detail on the WebArrow case study of agile architecting, including a number of architectural diagrams and additional description of the experimentation performed.

Ward Cunningham first coined the term “technical debt” in 1992 [Cunningham 92]. Brown et al. [Brown 10], building in part on Cunningham’s work, offer an economics-driven perspective on how to enable agility through architecture.

Robert Nord, Jim Tomayko, and Rob Wojcik [Nord 04] have analyzed the relationship between several of the Software Engineering Institute’s architecture methods and Extreme Programming. Grady Booch has blogged extensively on the relationship between architecture and Agile in his blog, for example [Booch 11].

Felix Bachmann [Bachmann 11] has provided a concrete example of a lightweight version of the ATAM that fits well with Agile projects and principles.

15.7. Discussion Questions

1. How would you employ the Agile practices of pair programming, frequent team interaction, and dedicated customer involvement in a distributed development environment?

2. Suppose, as a supporter of architecture practices, you were asked to write an Architecture Manifesto that was modeled on the Agile Manifesto. What would it look like?

3. Agile projects must be budgeted and scheduled like any other. How would you do that? Does an architecture help or hinder this process?

4. What do you think are the essential skills for an architect operating in an Agile context? How do you suppose they differ for an architect working in a non-Agile project?

5. The Agile Manifesto professes to value individuals and interactions over processes and tools. Rationalize this statement in terms of the role of tools in the modern software development process: compilers, integrated development environments, debuggers, configuration managers, automatic test tools, and build and configuration tools.

6. Critique the Agile Manifesto in the context of a 200-developer, 5-million-line project with an expected lifetime of 20 years.