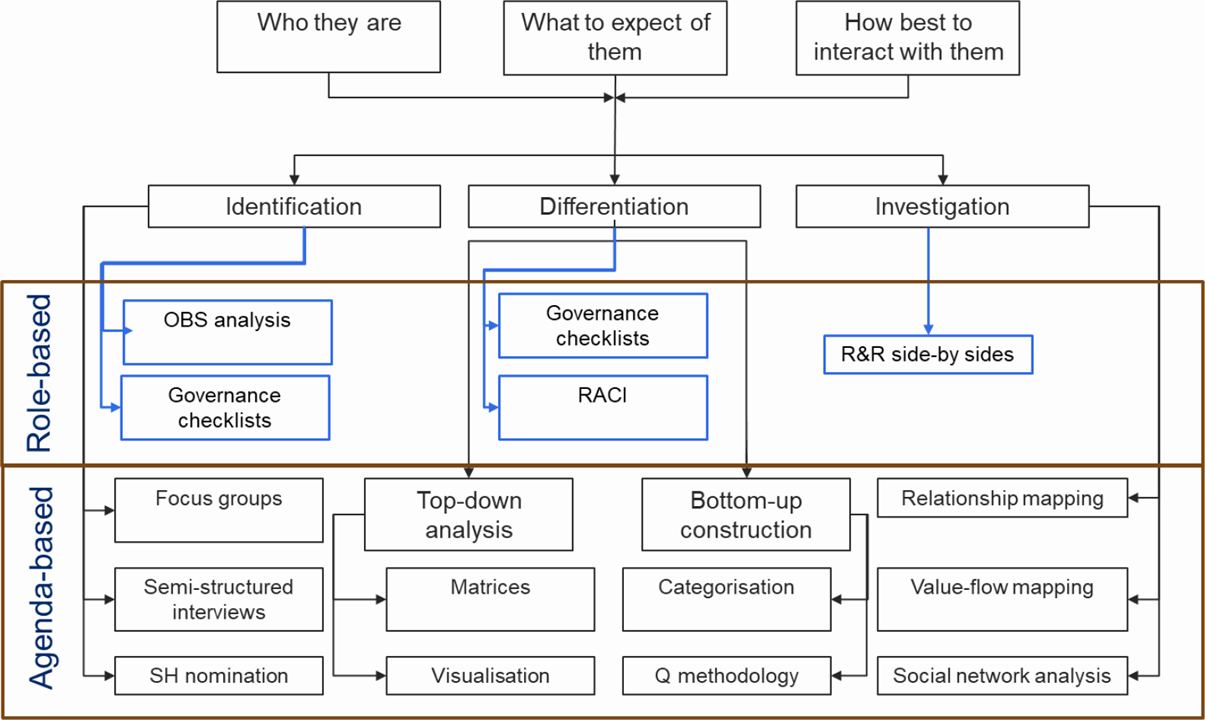

Stakeholder analysis is an essential input to planning and structuring the engagement of stakeholders before, during, and after the project completes. How we gather and analyze stakeholder information is, once again, context-sensitive (Figure 4.1).

During the initiation and analysis stages, three questions must be answered:

Who are they? This information is documented in the project plan or communications plan. It will include data such as name and job title, group name, group representative—everything needed by the project to know how to recognize and make contact with the group or individual.

What to expect of them? For role-based stakeholders, this is related to their role. Still, as we saw in earlier chapters, it is how the position has been interpreted by the individual, groups, and other players that must be clear and shared. In a project plan, this information is presented in the governance section—identifying the agreed roles and responsibilities for this particular project.

Agenda-based stakeholder modeling must take into account the perspectives of these stakeholders. This modeling may be presented through a stakeholder plan, which identifies positions, or more visually in mind maps and models such as the stakeholder circle (Bourne and Walker 2005). The choice of visual technique will vary depending upon what information is useful to the stakeholder classification. Common ones are the level of support toward the project. The example in Figure 4.2. uses happy faces to indicate project allies, while the black flags show a risk associated with that stakeholder—their views may be unknown or changeable.

Figure 4.1 Collecting stakeholder data

Figure 4.2 Attitude map

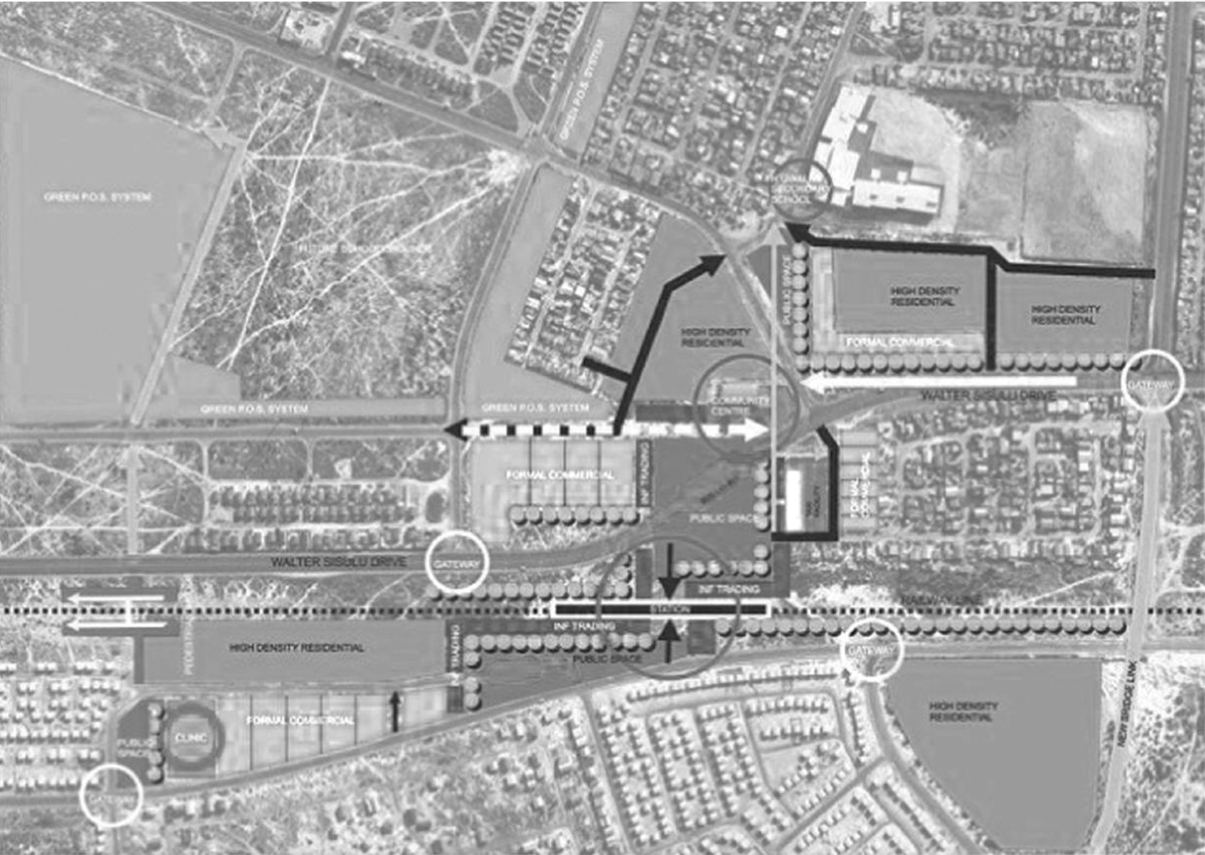

Other visualizations may be particular to the project context. The following extract is from a sustainability manager involved in social development and housing projects in South Africa. “When we don’t know what we don’t know regarding stakeholders, then it can be helpful to use techniques that allow us to ‘visualize’ the problem.” For example:

• Using a geographical map of the area—right down to ward level (Figure 4.3). Something happens when you look at information differently, and it can just spark a new thread of thinking.

• We also do location scouting—by driving through an area, town, or region—it does ensure that the obvious stakeholders do not get overexposed, and it raises questions about “Who we forgot?”

• We meet with tourism officials in a specific area to understand the issues. Once we know the problems, it is easier to identify stakeholders who may be impacted and who may like to be part of an engagement process.

• We also use media profiling, for instance, to see what is reported about a specific area—to identify new influencers or new stakeholder priority groups.

Figure 4.3 Geographical mapping of wards

The third of the three questions we need to pose is: How best to interact with them? For role-based stakeholders, this is described in the project plan. Project reporting is usually focused on providing specific roles, with status reports on project progress. Further information can be listed in the communications plan, showing what interactions will occur, and with whom. The communications and engagement plans for agenda-based stakeholders must take into account their perspectives, their powerbase vis-à-vis the project, their preferences for interactions with the project, and their likely reactions to any engagement. Agenda-based stakeholders may include large groups of people with no obvious leaders. The project needs to identify how these groups will be engaged with and which representation or delegation process should be used. It is not surprising that engagement planning for agenda-based stakeholders demands much more sophisticated analysis. This increased demand is another good reason for separating role- and agenda-based stakeholders. You have to address their concerns using different engagement approaches.

Figure 4.4 is an example of a relationship mapping—one of the techniques mentioned in Figure 4.1. Each stakeholder is described in terms of what we know about their relationship with the project. In this case, David seems to be neutral or negative, but this information is indicated as assumed, showing that further information is required to validate this belief. Gene, on the other hand, is shown as positive from observed behaviors. Analysis of agenda-based stakeholders will often contain information that is confidential and sensitive. How this information will be documented and shared must be carefully considered and strictly controlled.

Analyzing Stakeholder Roles

The biggest challenge in understanding role-based stakeholders is ensuring that there is a common and accepted view of the stakeholders’ roles and responsibilities. These are defined in general terms through governance structures. However, it is often the case that the prevailing model does not match the perceptions of the actual stakeholders. This problem may arise because of role slippage—changing interpretation of roles over time and through the introduction of new roles that muddy the picture as to who does what. The introduction of specialist roles (change manager, program manager, etc.) and new levels of governance (portfolio committee, program board, etc.) can make identifying who is responsible for what more and more confusing.

Figure 4.4 Stakeholder relationship mapping

In projects, role confusion causes issues such as:

• Lack of clarity about who should make a decision

• Questions about who does what?

• Stop-and-start on project activities as the project waits for issue resolution and decision making

• Blaming others for not getting the work done

• Out of balance workloads or work not being done in the correct area

• A culture of procrastination—“We’re not sure, so we’ll wait.”

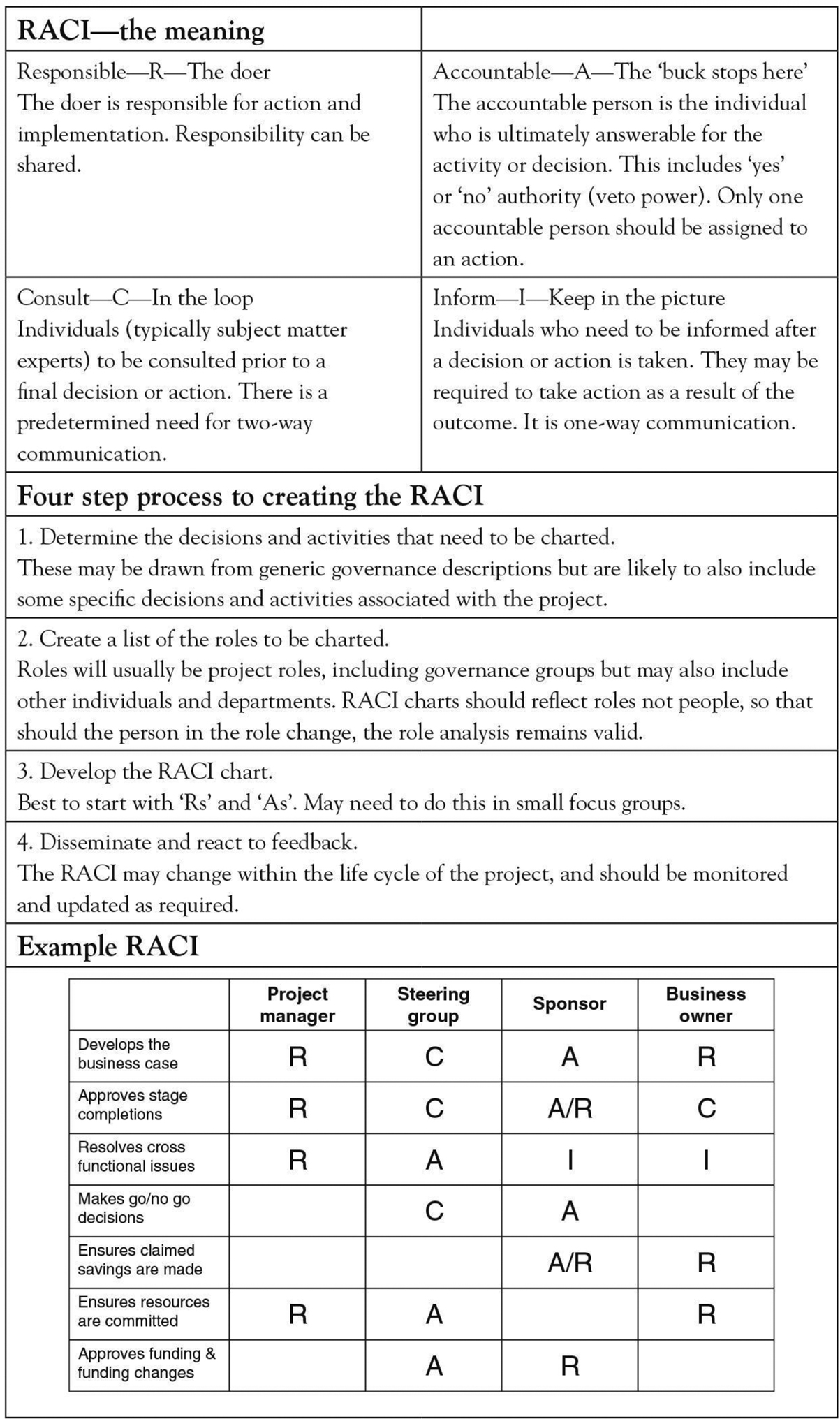

Responsibility charting (often known by the acronym RACI— Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) is a technique used to identify areas where there are process or decision-making ambiguities. The aim is to bring out the differences and resolve them through consultation and debate. Underpinning the approach is the insight that any particular role has three perspectives, which are often poorly aligned—what the person thinks the role is, what other people think the role is, and what the person does.

RACI’s power is in its ability to create clarity and agreed interpretations where they do not exist or where there is a tendency to encourage a lack of clarity as a device to hide behind. Figure 4.5 illustrates the approach. Communicating the understanding of the roles will often expose issues and areas that require further debate. In the example here, the sponsor has been made accountable for the approval of all stages, but maybe this should be stage-dependent. For example, it may be more appropriate for the business owner or a technical lead to take on accountability for approval of the products delivered in execution.

During the concept, initiation, and planning stages, RACI is particularly useful for ensuring governance clarity—who can make what decisions about what and when. During execution and close-out, detailed responsibility charts are crucial to ensuring the transparency of decision making and will tend to focus on responsibilities—the activities to be done.

Figure 4.5 The RACI approach

There is such a wide variety of models for analyzing stakeholder agendas. Here we present four models with examples of their use from case studies. Which one you choose to use will mainly depend upon how far along the stakeholder continuum your project sits.

Stakeholder Analysis Matrices

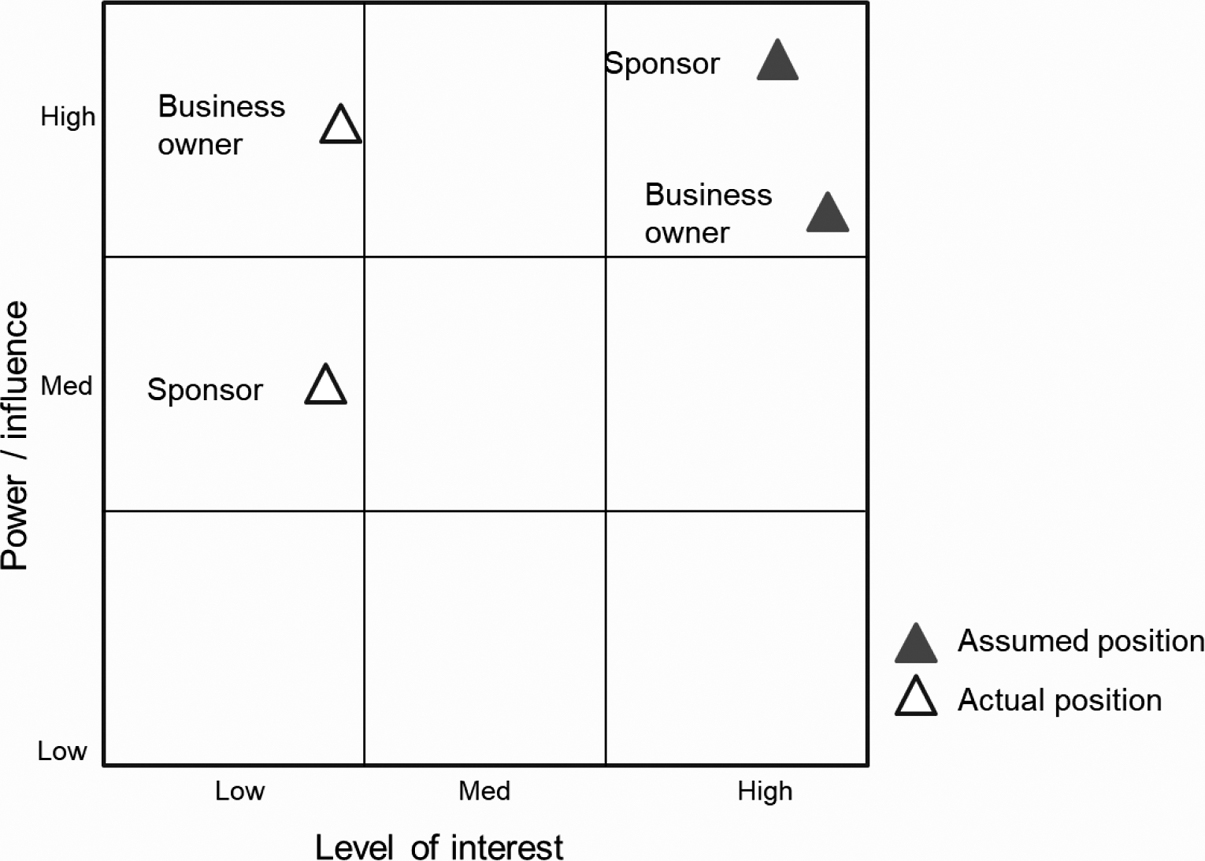

Stakeholder analysis matrices map attitudes of the stakeholders toward the project. The most commonly used of these is the power-interest matrix. In our exploration of stakeholder practices among project managers, we found that if a project manager used any analysis model at all, this was the one they were likely to use. It is, however, often used to analyze role-based positions, rather than the agendas of stakeholders, and this is a mistake. If you have ever used one of these and wondered why it did not help you much, then maybe you are using it for the wrong type of stakeholders. Or, you are using it without having sufficient information and insight into the real positions of the stakeholder you are trying to map.

When using the classic 3 × 3 matrix, such as the one shown in Figure 4.6, we invariably find that project managers place the project sponsor and business owner in the top right-hand box. Both are assumed to be interested in the project, and the business owner is usually thought to have less power and influence than the sponsor because they are typically subordinate in the organization.

This mistake was made in Case 4.1: The Credit Control Change That Never Happened, a relatively simple project, which at the close was reported as successful. However, in a post-implementation review, it was found to be an ineffectual application of time and money. No change in practices was found, and no benefits were realized from the investment. In reality, the stakeholders’ positions were much more like the actual positions shown in Figure 4.6.

Figure 4.6 Mapping stakeholders on a power-interest grid: In theory and in practice

Two common mistakes are illustrated here. The first is to assume that the sponsor is genuinely excited and interested in the project. The sponsor may hold the purse-strings, but they are often doing this for a portfolio of projects, not all of which will be of equal interest and priority to them. The second mistake is to equate power with organizational position and status. In XCO, the sponsor may be senior to the business owner, but it is the business owner who controls the resources on a day-to-day basis. It is the business owner who will ultimately take on the operationalization of the new functionality. In stakeholder analysis terms, it is vital to consider the power within the project context. Some of the analysis models we introduce later in this chapter attempt to clarify this by moving away from generalized terms like power and interest, which are easy to misinterpret,

The analysis of a stakeholder’s position must always be made in terms of their relationship to the project, and this may not be as obvious as just looking at what role they occupy.

Analysis models demand the characterization of groups and individuals. This first step is dependent upon how well the stakeholders are known and understood. On most complex projects, particularly where agenda-based stakeholders are involved, this can be a challenge. In their analysis of stakeholder identification in a hospital project, Jepsen and Eskerod (2009) found that the project managers lacked the skills, resources, and connections to be able to do more than a relatively superficial analysis of the project stakeholders.

Despite this lack of skills and knowledge, or perhaps because of it, there is a tendency to make assumptions about the characteristics of stakeholders. These assumptions are often based on how the stakeholder might be expected to behave in a project, rather than a real understanding of the particular wants and needs of the stakeholder who occupies the role.

Case 4.1

The Credit Control Changes that Never Happened

Company XCO had decided that it would be a good idea to extend the use of their financial systems to support the credit controllers. The system would provide information about the creditworthiness of customers and would enable credit controllers to prioritize their customer interactions.

Senior management and the sponsor thought it looked great and hoped it would take the pressure off staff who were often working long hours. The IT implementation was straightforward, and the IT manager felt that this would provide opportunities for further developments. The credit control team was briefed and were positive— anything to reduce their workload sounded good.

The system was implemented. At a review three months after the project, it was found that nobody in the department was using any of the new functionality implemented.

Comments

Senior manager: “We thought they were using it.”

Business owner: “It’s a good idea, but we have so much work on at the moment. I just couldn’t stop what we are doing.”

Team: “It looks great, but we just have not had time.”

The Stakeholder Interest Intensity Index

The 3 × 3 analysis matrix is the easiest to use as an analytical tool in a planning workshop. However, there is often insufficient understanding and agreement about the meaning of the terms used in the matrix analysis. This confusion can reduce the effectiveness of the tool. Rather than assume a shared understanding of words like power and interest, examples should be explored to ensure the analysis in the workshop is based upon a mutual and consistent approach.

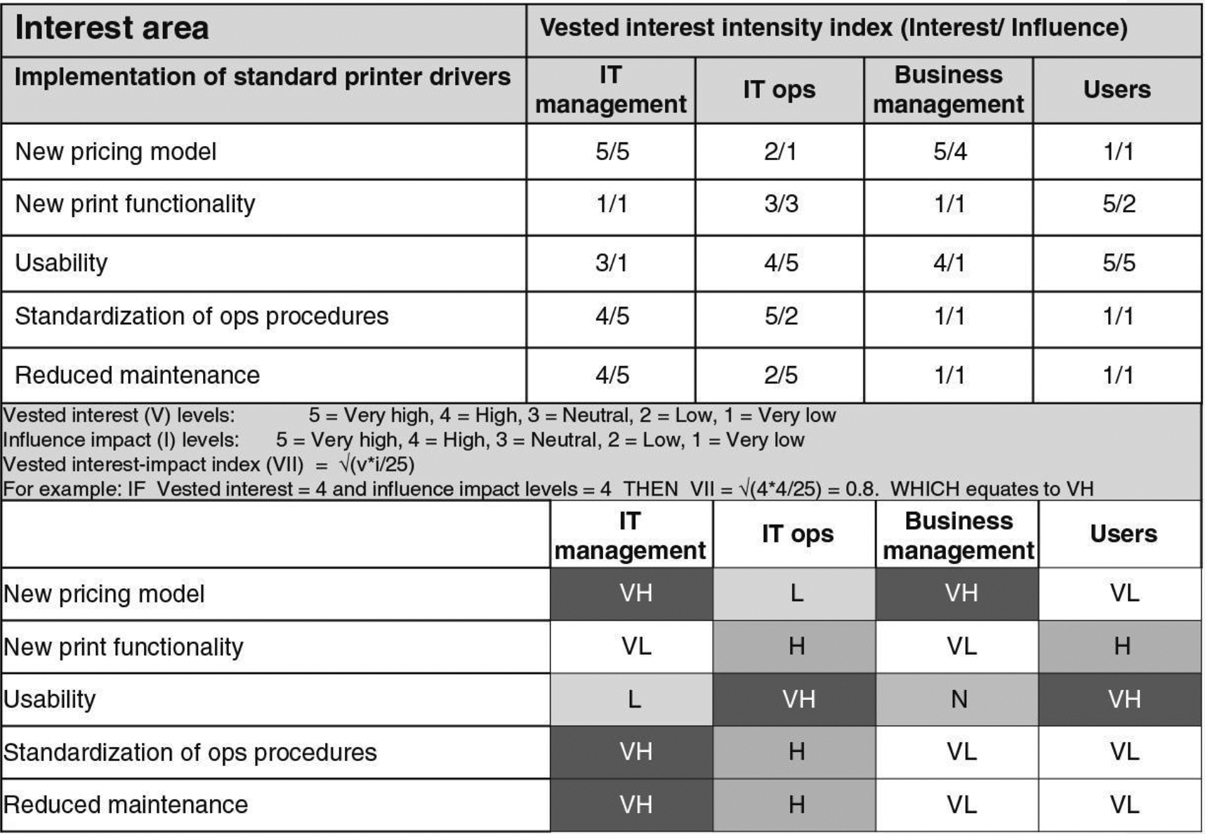

Bourne and Walker (2005) emphasize the importance of clarifying these concepts by quantifying stakeholder attributes. The stakeholder interest intensity index (Bourne and Walker 2005) is calculated from an evaluation of the interest and influence of stakeholder groups when considered against specific aspects of the project. This tool can then be used to create visual representations of the various stakeholder positions.

Figure 4.7 is an analysis of some of the stakeholders’ positions in the Like-for-Like project discussed in Chapter 3. It is apparent that the agendas of the stakeholder groups are quite different, with management mainly focused on new pricing structures, and the operational teams’ users much more interested in functionality and usability. The project must address both of these concerns, which may conflict. In reality, this project focused on the needs of IT management. As, however, the project progressed, the user discontent became so vociferous that the position of the business management stakeholders changed drastically—an excellent example of the changeability of stakeholder positions and how stakeholders can be influenced by other groups.

Figure 4.7 Stakeholder interest intensity index

The Stakeholder Salience Model

The stakeholder salience model (Mitchell et al. 1997) raises the issues of legitimacy (who has a claim?) and salience (who is really important?) as the critical factors in determining who should feature in the stakeholder engagement plan.

The model uses three stakeholder attributes: power, legitimacy, and urgency. The meaning of these terms need to be translated into a project context, as they come from a broader organizational base:

• Power: Stakeholders have power to the extent they can control access to project resources or can impact and influence the direction of the project or can affect the value returned by the project.

• Legitimacy: Stakeholders are legitimate to the extent that their actions are perceived (by socially constructed norms) as proper, appropriate, or desirable by the project.

• Urgency: The degree to which the stakeholder claims attention from the project and the speed of response demanded by the stakeholder.

The urgency attribute highlights the dynamic nature of the stakeholder relationship. This attribute obviously can change, and that is equally true of the others. A stakeholder group, through lobbying, can become legitimate. Indeed by choosing to engage with a stakeholder group, the project itself contributes to its legitimacy. A particular stakeholder may acquire additional attributes during the lifecycle of the project or project phase and thus merit a change in the level of engagement by the project team.

Stakeholders can be classified based on the presence of one or more of these attributes. Figure 4.8 shows the seven potential stakeholder types. The more attributes a stakeholder has, the more salient they are to the project, that is, the more they demand and justify the attention of the project.

Figure 4.8 Stakeholder salience

Source: (Mitchell et al. 1997)

As the project team begins to develop its strategy, it needs to assess the level and type of attention it will direct to the different groups. Table 4.1 summarizes the suggested actions for each of the seven stakeholder types identified by the model.

We can use this approach for Case 3.3: The Like-for-Like project (Figure 4.9) using input from the stakeholder interest intensity index described above.

• IT management: Definitive stakeholder. They have the power and legitimacy and are clear about what they want from the project, and they want this to happen now.

Table 4.1 The salience model—suggested engagement tactics

Stakeholder type |

Attribute |

Salience |

Actions suggested |

Dormant |

Power |

Low |

Not important now, but they may wake up. Watch and recheck. Beware of over communicating |

Dangerous |

Power + urgency |

Med. |

Stakeholders with an agenda and the energy to follow through. Meet agenda, or isolate their impact. |

Demanding |

Urgency |

Low |

High energy, but beware being drawn into over focusing. There are more important groups to work with. |

Dependent |

Legitimacy + Urgency |

Med. |

While these groups may not have power with respect to the project, they may have the ability to influence others who do. Watch relationships with other stakeholders. |

Discretionary |

Legitimacy |

Low |

Rather like dormant stakeholders, but not quite as dangerous should they wake up. Keep informed, but beware of over communication or attempts to over involve this group. |

Dominant |

Power + Legitimacy |

Med. |

Important to the project, but may have low interest and energy levels. Consider how to engage and to sustain interest in the project. |

Definitive |

Power + Legitimacy + Urgency |

High |

Sometimes referred to as core or key stakeholders. The roles and agendas of these stakeholders must be clearly understood and aligned with outcomes. |

Figure 4.9 Like-for-Like project: Stakeholder types

• IT operations: Definitive stakeholders. Similar to IT management, but they have more diverse agendas—it is not just about the money! They have closer working relationships with the users and have to deal personally with the users’ concerns.

• Business management: Dominant stakeholder. While they have power and legitimacy, this is not a particularly important project for them. The urgency levels and need to act are much lower (at the moment). That position can easily change. They are influenced by other groups, notably their staff (business users).

• Users: Dependent stakeholders. The users just want this done now, but their requirements go beyond just the pricing model. There are lots of them, and their needs may be quite disparate and difficult to pin down. While not acting as a single coherent group, their power levels are low, but should this change; then action will be necessary.

By combining the visual approaches with the salience model, we are beginning to start the diagnosis of the current situation and help identify where and how to direct project attention. The chosen strategy needs to shape the project plan in all aspects, ranging from communication and scope of work, through to planning and management of risks.

Sociodynamics Stakeholder Analysis Model

The sociodynamics stakeholder analysis model (D’Herbemont and Cesar 1998) combines aspects of quantitative analysis, powerful metaphors, and visual presentation. Their model is illustrated in Figure 4.10.

This model equates the stakeholder environment to a field of play, rather like a football pitch. For the project to be successful, it must attempt to understand and influence who enters the pitch and what positions they play. They argue that to manage the field of play, it is vital to segment it. The field is not made up of a simple list of key players. Instead, the project must gather people into homogenous groups, ensuring that there is a representative authority in each group. That said, it is still important to understand stakeholders as individuals and how they will react to the project.

Figure 4.10 Sociodynamics model: The attitudes toward the project (D’Herbemont and Cesar 1998)

Segmenting the field of play allows for the identification of those players acting for the project and those working against it. These two different positions are described as:

• Synergy: The energy in support of the project. Synergy uses the concept of initiative, defined as the capacity to act in favor of the project without being asked. High synergy is characterized as acting for the project without any prompting required. Low synergy is typified by stakeholders showing little interest in the project.

• Antagonism: The energy in opposition to the project. The amount of energy the stakeholder will expend in support of a competing agenda or alternative project. In the Like-for-Like project, a business manager who actively supports an alternative print strategy, such as outsourcing, would have high levels of antagonism.

Segmenting the field of play is not just a means of knowing the pitch, but also a mechanism for working out the moves to make on the ground. When the synergy and antagonism are mapped, they give rise to eight stereotypical stakeholder attitudes that we can recognize in our projects.

In sociodynamics analysis, the aim is to increase the number of project supporters through the way we engage with them. Using these stereotypes, we can re-analyze the Like-for-Like project and consider again the communication strategy to increase the support for this project.

Zealots and golden triangles are our main supporter groups. In the Like-for-Like project, this includes the IT management team and at least some of the operational team. Zealots are great champions and good for raising morale. They are uncompromisingly for the project and do not take criticism of the project well. They often find it difficult to appreciate and relate to the views of other players on the field, and for this reason, they are not generally very useful influencers. Our best influencers are the golden triangles. The Like-for-Like project should have ensured (through influence and the alignment of agendas) that at least some of each of the stakeholder groups took the role of golden triangles, and that they were encouraged to show their positive support.

The waverers are potential allies. They may have their doubts about the project and cannot decide yet on its merits—the what’s-in-it-forthem. In the Like-for-Like project, this includes some of the business managers and the operational team. The waverers are important because their attitudes genuinely influence the passive majority, who in the main are pretty suspicious of the zealots! The Like-for-Like project must keep close tabs on the position of this group. Changes in the project must be rechecked carefully against the opinions of these stakeholders.

The majority of project stakeholders are passives. These are the silent majority or more critically referred to as the dead-weights. They are important because of their sheer numbers (maybe 40 percent or more of stakeholders sit in this category), and because they can tilt the scales in favor or against the project. Many of the users, and at least a few of the business managers, sit in this category on the Like-for-Like project. They can be influenced by the waverers, but also by changes in the positions of known opponents to the project.

The opponents are against the project. They are sensitive to influence, unlike the mutineers, who are insensitive to any form of influence or force brought to bear to change their position.

In the Like-for-Like project, there were initially few if any opponents. The trouble was that the project grew in scope and business impact without close monitoring of the stakeholder positions. Some passives, and even some waverers and allies in the business managers and user groups, changed attitudes in response to significant changes in the scope and remit of the project. They became opponents and, in extreme cases, mutineers. Insufficient attention to stakeholder attitudes meant that the project found it increasingly difficult to sustain the synergy and positive support for the project. This failure was undoubtedly one of the major causes of its inability to complete.

Beware the Magpie Effect

Stakeholder analysis models such as the salience model are designed to address the problem—we cannot engage with everybody. Given the limited time available to the project manager, resources must be allocated in such a way as to achieve the best possible result. However, the over focus on a few individuals creates a different kind of problem.

Jepsen and Eskerod (2009), referencing the law of diminishing returns, suggest efforts are better directed toward a wider group of stakeholders than a concentrated focus on a few, as initial efforts yield a higher return than later efforts. This approach is supported by D’Herbemont and Cesar (1998), who describe the problem of the magpie syndrome where managers over focus on those stakeholders with the loudest voice—typically those who are opposing the project. As we see in Case 4.2: Student Management System, the additional effort is not valued nor valuable.

A similar magpie effect occurs when the project manager directs attention to those stakeholders they know in preference to those they do not. This focus on friends reinforces existing relationships, while new relationships required by the project context are left unattended. As one experienced project manager commented, “You know you are involved in stakeholder engagement when you start having coffee with people you don’t know . . . or like!” While this may sound overly cynical, it captures the stakeholder challenge; in some cases, the project manager will need to extend their networks well beyond the people with whom they currently have relationships.

Case 4.2

Student Management System—The Powerful Negative Stakeholder

The roll out of the new student management systems impacted the whole of the university, and the academic computing department and management services department needed to work together to ensure the seamless integration of the IT infrastructure.

The trouble was that these two departments never worked seamlessly together! This lack of cooperation was made worse by the increasingly poor relationship between the two heads of department. Meetings and communications between the two were frequent, time-consuming, and often acrimonious.

The focus of the project became to ensure that one or other of the two management heads won their battle. Staff and other stakeholders did not want to be involved in the conflict and, wherever possible, avoided meetings about the project.

When one of the heads of department suddenly switched attention away from the project and the conflict, the other stakeholders breathed a collective sigh of relief and gradually re-engaged.

Over focus by the project manager on a single, albeit influential stakeholder (the magpie syndrome), had nearly wrecked the project. Other engagement strategies should have been found that would have proved to be more successful, and the project’s success would not have been so reliant on an accidental event.

Successful project managers have great networks.

Stakeholder Groupings

The analysis and categorization of stakeholders enable the project to identify stakeholders who will be engaged with as a group rather than as individuals. One-on-ones with large numbers of individuals are likely to be impossibly time-consuming and expensive. Also, the grouping of stakeholders provides for a collective engagement process. To get the project stakeholder engagement right requires the identification of who fits into which groups.

In a top-down approach, the project will select and engage with groups based upon its view of how the project is to be structured. For example, a retail project that wishes to engage with its external customers may choose to group them by geography (state-by-state, north and south, etc.) by product line (food, clothing, etc.), or both. The decision on the groupings is impacted by several factors:

• The project delivery strategy: Technology, cost, and resource constraints may suggest the most efficient engagement approach from the project perspective.

• The nature of the envisaged engagement: Is the engagement primarily information-seeking, information-giving, general communication, or aimed at influencing behaviors and attitudes toward the project? The purpose, in turn, affects the ideal size and make-up of the stakeholder groupings.

• Existing consultation group structures: Consultation groups may be constituted by the project organization to aid and support regular consultation or may exist as independent legitimized groups, such as unions and public interest groups.

Top-down stakeholder grouping, where the project structure informs the stakeholder grouping, is most effective on stakeholder-neutral and stakeholder-sensitive projects. As we move along our project continuum toward stakeholder-led projects, it is the stakeholders and their agendas that primarily influence the way these projects are structured, not the other way around! In these projects, the stakeholder groupings will often emerge and change in line with the emergence and alignment of the agendas that form around the project.

Initial groupings in these projects may be anticipated through analysis techniques such as stakeholder-led classification and Q-modelling. These aid our understanding of the positions that any group may take at the start of the project. As the impacts of the project become more evident, and more people become aware of it, new interest groups may arise, and new groups may form and re-form.

The grouping of stakeholders, whether in stakeholder-neutral or stakeholder-led projects, is more significant than is often realized. It defines the touchpoints and conduits in and out of the project. The decision to engage through a particular group rather than interact with its members means that the project will be dependent on the representation of the group by its elected or emergent leadership structures. We may assume that there is coherence or homogeneity of views within the group about the project. Such assumptions are, however, often wrong. Members of the group have different needs and priorities. Group-based engagement operates on the principle that the group will have mechanisms that enable it to accommodate these differences. Sometimes, tightly-knit groups can come to a consensus view, which will be supported by the whole group. But, very often, this sort of cohesiveness and identity of viewpoint does not exist.

Where the project has legitimate power and influence recognized by the group—for example, it has well-structured governance—engagement issues can and should be addressed through the normal governance processes. For other groups, when the group dynamics break down, the project has to consider the best course of action carefully. Is it better to allow the group to fragment, or should the project provide facilitation and arbitration processes to support the group decision-making process?

In Summary

This chapter has introduced various analysis models to aid the development of appropriate communication and engagement strategies. Without useful information and understanding of the stakeholder agendas, analysis always falls short. Too often, unfounded assumptions are made about stakeholder positions. These must be tested as part of the analysis process.

• To analyze stakeholders, you need to gather information on them. Poor information leads to poor analysis.

• Analysis tools help verify who the stakeholders are (who we have missed or might miss) and what to expect of them; from this, engagement strategies may emerge.

• Stakeholder visualization tools support identification and may also be used to monitor and track changes in the position of project stakeholders.

• Stakeholder matrices use stakeholder characteristics such as power and influence to map out the stakeholder environment. The salience model and the sociodynamics model provide powerful metaphors that support the visualization of how stakeholders may interact and be influenced by other groups.

• Projects will always have limited resources, and therefore, the focus of these resources on the right stakeholder activity is crucial. Ultimately, the project should focus its attention on those who can have the most significant positive effect on success, now and in the future.

• High-performing project managers maintain networks of relationships and develop strategies and tactics to create the new relationships demanded by every project.

Reflections

1. How has your network of stakeholders changed in the last few years?

2. Do you have templates or checklists for the role-based stakeholders on your projects? Do these need to be revisited and revised to meet the specific needs of your project?

3. For your current or a recent project, create a stakeholder interest intensity matrix. What insights does it provide?

4. For your current or a recent project, use either the salience model or the sociodynamics model to identify the attitudes and likely communication strategies for your stakeholder groups. What insights does it provide?