Communication is, by its very nature, a form of engagement, but stakeholder engagement is more than just communicating. I might notify you by sending you an e-mail. You may have received and understood the message, but how engaged are you? I have sent the message, so can I tick my communications plan? But, can I be sure you are engaged or will stay engaged?

I need the business owner to help to get staff in the credit control area to use the new system functionality. We meet and discuss the best way of getting this to happen. The business owner comes up with some ideas on how to get the message over, and they agree to an action plan. If that starts to work, then we have engaged stakeholders!

From Communication to Meaningful Engagement

In Chapter 1, discussing myths, we argued that the management of stakeholders implies coordination and control, and these terms are inappropriate to the vast majority of stakeholders, particularly agenda-based stakeholders, where the project can, at best, only influence their positions. Where projects exist in matrix structures, even role-based stakeholders, expert resources, and team members may not be owned by nor can be managed by the project.

Engagement, as the term implies, is a much more participative process. It means a willingness to listen to stakeholders, to discuss mutual interests, and to be prepared to modify the direction or the conduct of a project based upon stakeholder input. All projects, even stakeholder-neutral ones, are born out of a consultation process with the project owners. However, as we progress to the right along the stakeholder continuum, engagement involves more stakeholders, and the impact of agenda-based stakeholders becomes more significant. This type of engagement demands greater collaborative involvement that is meaningful to all participants.

Jeffery’s (2009) report on stakeholder engagement in social development projects asserts that “meaningful engagement is characterized by a willingness to be open to change.” He identifies four changes in practice that are needed to achieve this:

• Management style: Not just seeking stakeholders out but working with them to determine who is and should be involved

• Involvement: Not just about predicting who will get involved but encouraging stakeholders to get involved

• Timing: Not set and imposed by the project, but the process and schedule for engagement are mutually agreed

• Attitude to change: Not protecting project boundaries but exploring and deciding on them with the stakeholders

These changes demand participation between the project and its stakeholders throughout the life cycle of the project. They also change the nature of the relationships between the project and its stakeholders and resonates with several practices that play a crucial role in Agile. As we saw in the stakeholder-sensitive cases discussed earlier (e.g., Case 2.3: The Cape Town Integrated Rapid Transit (IRT) and Case 5.8: Eurostar: Taking Our People With Us), the engagement process becomes a joint endeavor requiring open consultation and the building of trusted relationships.

Figure 6.1 is an extended stakeholder management process illustrating four additional steps in the engagement process:

Step 1—Internal preparation and alignment: The manager in the Cape Town IRT stated that knowing your stakeholders’ agendas was critical. All the stakeholders must be taken on the journey. Without developing the support of the City Council for solutions proposed by the IRT business transformation project, the IRT project could not have been successful. Building internal support, perhaps for political reasons that have nothing to do with the project, can prove harder than gaining the support of external groups. A business case may be required, but perhaps more importantly, is the need to develop internal advocates—champions and believers in the proposed plans.

Figure 6.1 The extended stakeholder management process

Step 2—Build trust: Different stakeholders will come with different levels of trust and willingness to trust, and that needs to be factored into the approach taken. The type of consultation that can be effectively used will depend upon the nature of the relationships between the project and those groups with which it needs to consult.

Step 3—Consult: Communication must be purposeful and must provide a credible platform that illustrates a genuine desire to consider stakeholder input—not just pseudo-consultation, which looks amusing until you experience it (Figure 6.2)!

Figure 6.2 Pseudo consultation

Source: dILBErt © 2012, Scott Adams. Used by permission of UNIVErSAL UCLICk. All rights reserved.

Genuine consultation is more than just communication, and to achieve this, we must ensure:

• Fair representation of all stakeholders: Not just the easy ones (those that we know and will come willingly to the project table), even if including them results in delayed actions and decisions.

• Complete and contextualized information: Stakeholders need a holistic picture of the project and its likely impacts. In Case 3.3: The Like-for-Like project, information on the effects of the technology changes were fed piecemeal to an increasingly growing group of stakeholders. The big picture was shared only with the inner cabinet of stakeholders, and there was a perception that other stakeholders “did not need to know.” This approach ultimately resulted in the breakdown of trust between the broader stakeholder group and the project.

• Broad consideration of all the options: Information and proposals should address those concerns and issues raised by all stakeholders, not just the concerns relating to internal project objectives. If consultation is to be credible, there must be visible evidence that information is being considered during the consultation process.

• Committed and realistic negotiations: Tradeoffs are likely to be necessary if the consultation is genuine. That means ensuring that the negotiators have the power and backing to consider the compromises needed. Trust is easily lost if the promise for negotiation repeatedly results in no change in position.

• An appropriate and planned-out consultation process: This should be deliberately designed around the purpose of the project, not just based upon a generalized method of communication.

• Consultation mechanisms that are relevant and acceptable: One size does not fit all, and the choice of the consultation approach matters. Personal interviews, workshops, focus groups, public meetings, surveys, participatory tools, and stakeholder panels—each facilitates different types of discussions. The location and timing of the consultations can also make a difference in the perceptions of the audience. Have you ever agreed to be part of a community group only to discover that meetings occurred on a Tuesday at 11 a.m.? You might be forgiven for declining, and perhaps thinking, “Clearly, they don’t want working people at those meetings!”

Step 4—Respond and implement: Responses in stakeholder engagement must visibly demonstrate how input from stakeholders has been heard, considered, and factored into the project. When discussing the lessons learned from the City of Cape Town IRT project, the project manager emphasized the importance of making sure the stakeholders can hear their voice in the read back.

In projects, particularly stakeholder-sensitive projects, every communication is a form of engagement. To create meaningful engagement demands a paradigm change. Not the management of stakeholders, but the creation of space, time, and a culture for participation and collaboration. In the increasingly complex projects of today, where agenda-based stakeholders are increasingly aware of the power they hold, it may be wise to remember:

Projects can no longer choose if they want to engage with stakeholders or not; the only decision they need to take is when and how successfully to engage. Jeffery (2009)

Stakeholder Sources of Power

Stakeholder analysis models commonly use power as one of the factors to consider. The stakeholders’ source of power determines the potency of the impact that a stakeholder may have on the project, and the way it gets expressed.

“The ability to understand the, often hidden, power and influence of various stakeholders is a critical skill for successful project managers” (Bourne and Walker 2005).

So being able to tap into the power sources of the stakeholder groups is crucial in projects, but the concept of power can be a little slippery.

Figure 6.3 Three dimensions of power, Lukes (2004)

There are three dimensions of power (Figure 6.3). The first, overt power, is relatively easy to identify when it is being used. They make it quite clear. They make a decision, and the results flow directly from that decision. That is why it is called overt. It is the open use of naked power. The primary sources of overt power are summarized in Table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Sources of power

Source of power |

Brief description |

Positional (authority) |

Arises from the position occupied in a hierarchy—the higher up in the hierarchy, the greater the power. |

Resource |

Based on the control over resources that give the ability to get things done. |

Expertise |

Based on the respect for knowledge and skills (information), an individual or group has that directly bears upon the matter at hand. |

Negative |

The power of veto—often underestimated but is ultimately the basis of democracy. It is how the passives win contests! |

Project governance structures, such as steering groups, are set up to establish avenues for overt power—authority, resource, and expertise—to be channeled into projects. Projects are transient structures and would otherwise not have natural sources of legitimate power. However, positional power derived not from the project governance, but from the organizational structure, can often interfere. It is not unknown for IT directors, for example, to believe they have the right to give direction to or veto a project which involves IT, regardless of whether they are part of that project’s formal governance structure.

Expertise power can sometimes be overlooked or overwhelmed by the priority given to positional and resource power. However, many projects depend on gaining agreement from respected experts in a particular field. Case 6.1: Moving to Modular Courses clearly illustrates the dominant position that experts can hold if their expertise is so great that no decision relating to their field is made without their clearly stated agreement.

Case 6.1

Moving to Modular Courses at a UK University (The Expert Stakeholder)

The program of change for converting all the undergraduate degrees into modular courses had a steering group made of the management team plus a small group of deans representing the faculty areas. The group met at least once a week in the early stages to review and approve the overall program brief. One of the common questions asked by the vice-chancellor was—“Has Peter seen this?” The program manager was new to the organization, and it took several weeks for her to realize the significance of this question.

Peter was not part of the governance group, not even part of the management team, but he had been the student administration analyst for over 30 years. Every decision that might affect student intake numbers impacted university income, and the calculations and assumptions on which these were based were very complicated.

While Peter did not have positional power and would not be accepted as part of the steering group’s structure for a whole range of political reasons, nobody wanted to make a decision without his approval. The program manager eventually set up a pre-steering group consultation involving a small number of experts. Their input was taken forward into the steering meetings.

The second dimension is influence power. Influence has several sources, and there is less uniformity in how they are named or recognized. Some are well known: status, charisma, and coercive power, while others have less widespread acceptance and include connection or referent power, and reward. (See Table 6.2 for brief definitions of these types of influence power.)

Table 6.2 Sources of influence

Source of influence |

Brief description |

Coercive |

Influence based on fear of punishment |

Status |

Influence based on social approval, for example, standing in the community |

Charisma |

Influence based on personal magnetism—the ability to get others to follow |

Reward |

Influence based on the ability to incentivize and reward |

Connection |

Influence based on a connection with others who are regarded as having power |

In Table 6.2, we summarized five sources of influence that may be used by a project:

• Reward and coercive strategies are the classic carrot-and-stick approach. These give short-term gains, but often do not provide sustained commitment from stakeholders. The value of the reward dwindles over time. The threat diminishes. Although discussed in the context of project management, these types of sources of influence are more commonly used in line management.

• Charisma is an example of the manifestation of personal power and is about the ability to get others to follow. In projects, this is most appropriately situated in the business sponsor or champion. Charismatic leadership by a project manager can be dangerous, as it may undermine the position of the sponsor.

• Connection as a source of influence relates to who you know and the power networks that can be tapped. This source of influence is particularly apposite on projects that often have to extend beyond traditional organizational boundaries and work outside usual managerial reporting lines. The importance of a project manager’s extended personal and professional networks was touched on in Chapter 3.

• Status makes a project attractive to stakeholders. If a project is prestigious, perhaps it is known to be of strategic importance, or simply has high visibility, then it attracts the interest of stakeholders. Projects without status can battle to attract the necessary commitment.

The impulse to act in compliance with the wishes of another is the mainspring of influence. The suggestion is followed not because you have been told to—an exercise of authority—but because she asked you to, and she commands your respect, or he is charismatic, or you are afraid of the consequences of not following his request. Effectively, you have been influenced. Influence power is much more frequently used in projects than in operational or line environments. Line management is built around command and control, or overt power structures, while projects more often get things done by influence and negotiation.

Case 6.2: The Power of Influence is an example of how purposeful communication and engagement are intimately linked. The effective application of influence power accomplished much of the persuasion. The agreement to act in the way the program wanted did not occur because of the force of the argument or through smart marketing, but by direct personal power influencing what others did.

Case 6.2

The Power of Influence

The Board of a Prison Service established a program to deliver a series of important reforms. The organization was strongly hierarchical, but each prison was essentially a fiefdom, with the governors of each prison jealous of their prerogatives. Though the program had powerful backing, the implementation could be easily undermined if the prison governors did not genuinely take on the new approach. The balance of power between the program and these agenda-based stakeholders—prison governors—was such that telling the prison governors what they had to do would not work. To gain the necessary real commitment, the program manager was chosen for her combination of sources of influence power. She was well known and highly respected for her previous work in a number of the prisons; she was well-liked and regarded as apolitical, and also, as the program manager, she had direct access to influential individuals on the Board, as well as outside the prison service.

During most of the program, though nominated as the program manager, she had to delegate the majority of the technical aspects of its management to others. Her time was entirely taken up with the activities associated with persuading individuals to energetically carry out the wishes of the program—convincing them that that is what they wanted to do.

The third power dimension is covert power. Being hidden from public view, its impact is much more insidious. It influences peoples’ actions and may mislead them into wanting things that are, in fact, contrary to their own best interests.

The most familiar way this power is exercised is in the control of agendas and information. By dictating what can be discussed, and what is known, the impact on decision making in projects is enormous. It is well known that “he who sets the agenda controls the outcome of the debate,” because though the approach cannot tell people what to think, it is stunningly successful in determining what the governance group thinks about. Much of what is regarded as political power is derived from covert power and the control it provides over those with overt power—those individuals entrusted with making decisions.

The use of covert power does raise several ethical issues around what the criteria for morally acceptable engagement with stakeholders really are? If the project has an unstated ulterior motive and seeks to engage in deceiving, this could be seen as an abuse of power. And, the converse may also be the case, with stakeholders supporting a project to gain an advantage in an otherwise unconnected matter.

Of course, in any real-world situation, the sources of power available to individuals will be a combination; for example, positional power may bring with it status and an element of coercive power. Ultimately power is manifest in the strategies chosen by the stakeholders, for example:

• Withholding or constraining the use of resources: This is when stakeholders restrict access to critical resources controlled in their area, either by reducing the availability of the resources or by putting conditions on their use.

• Coalition-building strategy: Stakeholders seek out and build alliances with other individuals with common agendas. Such collaboration enables the more powerful group to have greater power and salience impact on the project. Case 3.3: The Like-for-Like project demonstrates this.

• Credibility-building and communication: Stakeholders use media and other public communications to increase the legitimacy of their claims concerning the project.

• Conflict escalation: Stakeholders can attempt to escalate conflict. Essentially a troublemaking process, the aim is to slow down the project. It may also attract additional stakeholders or awaken sleepers, quiescent stakeholders of the project. In the Case 2.3: City of Cape Town IRT project, this was a significant concern. The taxi associations had, in the past, resorted to violent demonstrations to block actions by the city council.

When dealing with stakeholders, it is always necessary to understand what their sources of power are. What actions are they likely to take, and what steps can they take, informs the engagement strategy.

Power and The Engagement Strategy

We have looked at several stakeholder analysis models. Some of them (like RACI) are most appropriate to role-based stakeholders. Others, like the salience and sociodynamics models, help us understand agendas and start to suggest approaches to engagement. In Case 6.3: The Maverick Stakeholders, we apply the analysis of stakeholder power using the sociodynamics model to a project to support the identification of who should be engaged with and how.

In this project, a deliberate decision is taken by the project to involve stakeholders who were not positive about the business or the project. The project manager called them the mavericks. The project team was made up of individuals who were generally disenchanted with the workplace and had little trust in management’s ability to change and improve the bank practices—not natural supporters of the project. The strategy was successful. Why? And, what learning can we take from the application of stakeholder analysis models?

Case 6.3

The Maverick Stakeholders

At a UK bank, customers’ complaints were rising, and the number of people in arrears was spiraling out of control. The problems had reached the board level in the bank, and a solution just had to be found. What was going wrong? From all accounts, the bank processes and policies were executed appropriately, but they just were not having the right effect.

With tight timescales and the need to make rapid and effective changes, it was decided to set up a project team. Bakr was to advise the team from a knowledge management perspective and to provide support and guidance to the new project manager who was business-knowledgeable, but relatively inexperienced in the running of projects.

The project started with an investigative stage to figure out the root causes of the problems. The change director, who was also accountable as the business sponsor, was keen to select the best frontline staff to be part of this team. But, Bakr was not convinced. These people were the ones supportive of and using the current processes—the processes that were already shown not to be working. Instead, he suggested picking a maverick team—using staff who complained about the current approaches—the ones who were always saying there was a better way. At first, the management team was skeptical; after all, these staff were the difficult ones, the ones who were not performing under the current approaches. Bakr was persuasive and got his team of eight mavericks who were interviewed and selected as people who doggedly questioned the way things were done.

This kind of team is not the easiest to manage, and careful consideration was put into structuring the environment and team engagement. For the investigation to be effective, these people were encouraged to try things that were out of the norm and sometimes even counter to standard policy. They were empowered to take the actions necessary, and the management team supported them through this process.

The team was co-located in one bank site, and the trickiest client cases were selected for their attention. For three weeks, each day, the team dealt with 50 to 60 cases. At 3 p.m., the reflection and analysis began. In a room full of flip charts, Bakr and the project manager facilitated the gathering of the stories from the day. What was going wrong? What practices seemed to work? What could they try doing to sort out the problem? The team was encouraged to think out of the box and to put themselves into the customers’ shoes: “If it were you, what would be good for you?”

Within one month, the success achieved by the team was phenomenal—from a starting point of just 22 percent to a massive 94 percent of payments paid and on a defined payment schedule.

Let us look at the power positions first. It is tempting to assume that these relatively junior staff have low power. However, it is not the power within the organization, but the power and control over the project and its ability to be successful that ultimately matters.

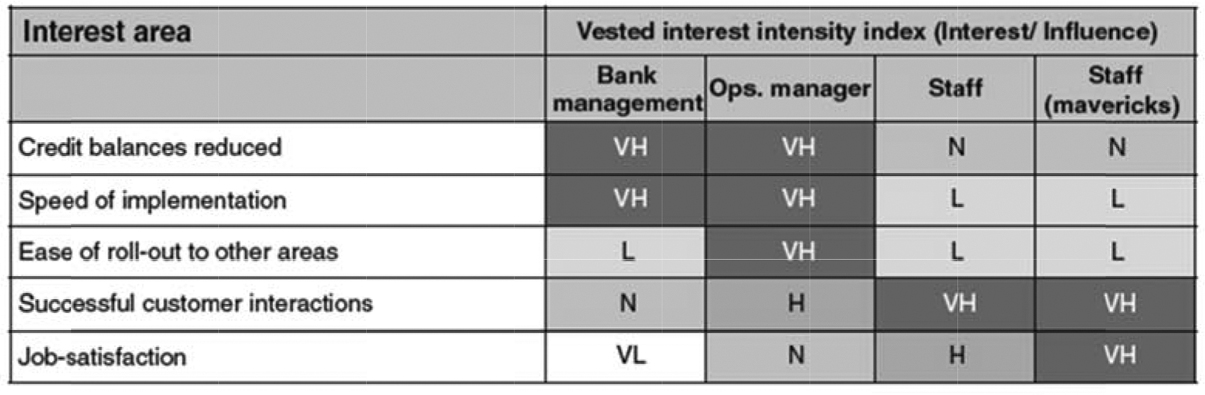

Using our understanding of the power and interest of the stakeholders, we can start to assess the stakeholder agendas (Figure 6.4) using the vested interest index (VII).

Figure 6.4 Evaluation of interest and influence for Case 6.3

As can be seen in the matrix, VII differs markedly between the management team and the operational staff. Mapping the interests and influence against the success areas for the project provides visibility of what is likely to be the key drivers for these stakeholders:

• The staff who will operate the process are most interested in job satisfaction, which comes about at least partly by improving the success of the interactions they have with the bank customers

• Successful customer interactions is the area where there is the most agreement between all the stakeholders

• The ease of roll out to other areas is a success factor for the project, but only one of the stakeholders has a high VII for this—the operational manager

• The maverick team has a higher VII for job satisfaction reflecting their current dissatisfaction levels

Now let us consider the power positions of these stakeholders. That means understanding not only the current power position of these players, but also their predicted power over the life of the project.

Table 6.3 describes the sources of power identified by the project manager at the start of the project. Here you can see that, as is common in stakeholder-sensitive projects, the power in the earlier stages may reside primarily with the management team. Still, other stakeholders become more significant as the project moves into operations. During transfer-to-operations, the power of the staff executing the new processes increases. How positively they take on the new processes will make the difference between long-term success and failure. Once they are operating the new process, these staff will become the experts, and the project will ultimately be reliant on this group to support the championing and roll-out to other teams.

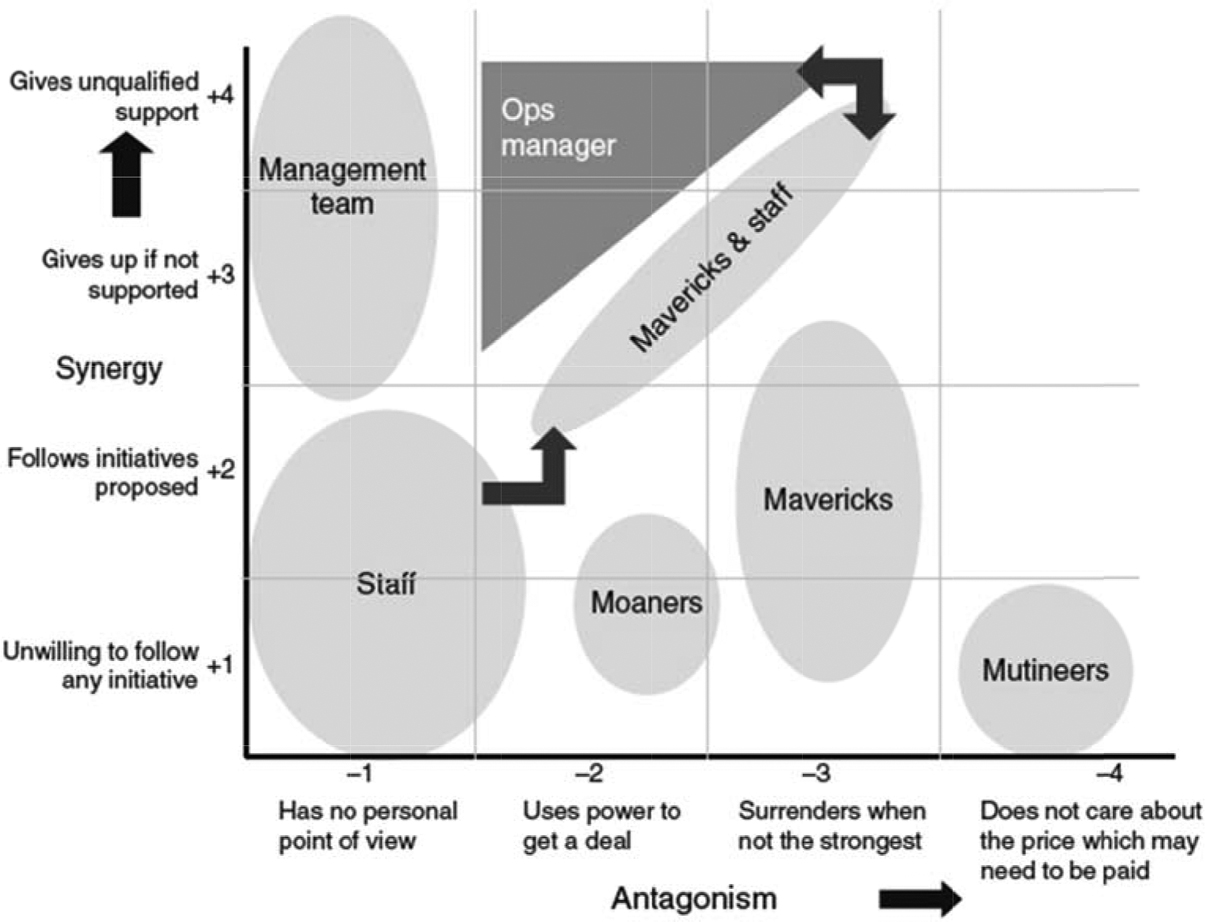

Having analyzed the stakeholders’ positions and power bases, the question remains as to what positions we need them to take and how we influence the stakeholders to adopt these. Figure 6.5 shows the stakeholders on the sociodynamics field of play. It maps the positive and negative energy levels (synergistic and antagonistic) toward the project.

Table 6.3 Predicted sources of power across the project (Case 6.3)

Initiation |

Execution |

Operation |

|

Management team |

Positional |

Positional |

|

Operational manager |

Positional |

Positional |

Positional |

Expertise |

|||

Staff |

Expertise |

Resource |

Resource |

Expertise |

|||

Staff (mavericks) |

Expertise |

Resource |

Resource |

Negative |

Expertise |

Figure 6.5 Analysis of maverick team sociodynamics position (Case 6.3)

The management team, with very high positive energy about the project, are the zealots. Given the crisis in the bank, they want this project to happen at all costs and will give unqualified and even irrational levels of support.

For the staff, any change is likely to be received with suspicion or disinterest. Many will have little energy for the project—the passives.

Some staff are known to have high levels of energy about their current job processes. These are the staff categorized as the staff mavericks by the project manager. This energy may be channeled against the project (opponents), “not another management initiative.” Alternatively, it could be directed positively into the project (waverers), or better still, golden triangles—“maybe something will happen at last.”

The sociodynamics model suggests that the energy levels of the staff need to increase from +2 to at least +3 on the synergy scale. Given the project success factors, the increased success of customer interactions and the need to be able to roll out the process quickly across the company, it is not enough to have staff that follow the initiative. The project needs to create staff who take the initiative forward and can sustain the changes with energy and enthusiasm. So, which of the staff should be selected to spearhead this work? Who are the allies we should target for the project?

Discussing the sociodynamics map, D’Herbemont and Cesar (1998) describe the concept of the ally further:

• Zealots and golden triangles are our first order allies. They will help lead support for the project. At the start of the project, this includes the management team and operations manager.

• The waverers are potential allies. They should be our targets. In this case, some of the staff.

• The passives are the real prize. The direction they choose to move in—positively or negatively—determines the success of the project.

In Case 6.3: The Maverick Stakeholders, the segmentation of the stakeholders known as staff, was always going to be a critical factor. Bakr rightly suspected that the mavericks would bring energy and more critical thinking into the development of the new processes. But, the management team concerns were not unfounded—get the wrong mavericks, and they could undermine the whole process.

As shown in Figure 6.6, it was essential to be able to distinguish the positive mavericks (the waverers) from the moaners. Bakr took great care in identifying the team selected from this group. This team, with the operational manager, would need to be able to come up with the ideas and become champions of the new process. Their enthusiasm for the new approach would need to infect and influence other staff to want to become involved, to increase the positive energy levels from the position of passives. But, would they be effective in doing this?

Figure 6.6 Targeting the change in stakeholder positions (Case 6.3)

As identified in the VII analysis, the roll out was an important aspect. Yet, this only had the attention and support of the operational manager. This lack of general support should alert us to the need to consider how the segmentation and engagement of stakeholders could be used to ensure the sustained success of the roll out.

Case 6.3 (Addendum)

The Maverick Stakeholders

There is little doubt that this approach transformed a group of mavericks into a team who were passionate and empowered to take forward and replicate the lessons learned in other operational areas.

But, the transfer to other areas was not as straightforward as hoped. Despite considerable evidence that the processes worked, it proved difficult to convince the staff in the subsequent rollouts that this was the right approach.

There is a clue as to the danger of only using the mavericks in the pilot group. It is clear from the analysis in Figure 6.6. While the use of mavericks addresses the immediate need for increased positive energy, it is still not clear what factors will influence the staff involved in the broader roll out. Case 6.3 (addendum) ends this story, and in reflecting on the outcome, three additional factors emerge:

• As the traditional non-conformers in the department, the mavericks proved to have weaker networks with other staff.

• The choice of these non-conformers was viewed with suspicion by some of the other staff—why them and not us?

• The mavericks were known for doing things differently from everybody else, and this prevented them from being natural allies for the rest of the staff to align with.

This project met its short-term objectives but faced additional challenges in sustaining the improvements. Stakeholder influence strategies must take into account the near- and long-term objectives, but most importantly, must consider the interactions between the various stakeholder groupings. These often have more influence on project success than direct project-to-stakeholder interactions.

The Power of Stakeholder Networks

Case 6.3: The Maverick Stakeholders, showed the importance of considering the relationships between stakeholders and how by influencing one group, others can be persuaded to change their positions. It is not just about the relationships between the project and the stakeholders, but about the networks of relationships that exist between stakeholders.

As projects unfold, the stakeholder network becomes denser. That is to say, the number of direct links that exist between stakeholders increase. The denser the networks become, and the more stakeholders communicate with one another, the more influence they can exert on the project. Fragmented stakeholder groupings without such ties are more likely to exhibit multiple conflicting stakeholder influences. Their fragmentation limits their ability to place pressure on a project. Random individuals who are against initiatives such as the development of the High Speed 2 (HS2) train in the United Kingdom have little power. But, give them a name and an avenue for sharing and communicating their concerns, and you have a concerted, organized power group with Twitter hashtags!

During the early stages of Case 3.3: The Like-for-Like project, no attempt was made to bring together the stakeholders in the many business groups impacted. Each group’s concerns were dealt with on a business unit by business unit basis; the concerns were raised, the local group was assured, and the project moved on. However, as the project timelines were extended, a powerful alliance of business managers started to emerge with shared concerns about the new printer devices implementation. This group proved much more difficult to persuade or to counter.

Each case raises a dilemma for projects. Should the coalition of stakeholder groups be facilitated—essentially, get the pain out of the way early? Or, should the project deliberately keep these groups apart to reduce the risk of powerful opponents arising? Both of these strategies may be considered divisive and raise ethical concerns.

Project Influence and Persuasion Strategies

Power may be seen as having the wherewithal to force or oblige changes in the behavior and actions of others and make them do things that they might not do otherwise. Influence is where peoples’ perceptions of a situation are altered so that they now make decisions, take actions, and behave in ways that are aligned to others’ agenda, and which they believe is also theirs.

In our final case study (Case 6.4: Modularization), we look at an example where specific influencing techniques were used to great effect. The techniques were based on the work done by Cialdini (2007). He identified six influencing techniques—or principles—that he had observed and which he believes underpins legitimate attempts to persuade individuals and groups. They are set out in Table 6.4.

In brief, he suggests that people are inclined to go along with suggestions if they think that the person making them has: credibility (authority); if they regard the person as a trusted friend (likeability); if they feel they owe the other person (reciprocity); or if agreeing to go along with the suggestion is consistent with their own beliefs or prior commitments (consistency). They are also inclined to make choices that they think most other people would make, “making them one of the crowd” (social approval). The sixth and somewhat odd, but compelling principle is the fear of missing out (scarcity). Fear of missing out appears to be a more potent influencer of action than a desire to gain an advantage— something used tirelessly by salespeople as they claim, “There are only two left!”

People tend to follow these principles because they usually lead to making acceptable choices. All of these factors are used, usually unconsciously, to persuade others. When used well, and to good effect, the individuals employing them are regarded as being socially adept, and acquiring the techniques is seen as part of the process of socialization and maturing.

Table 6.4 Cialdini’s six principles of social influence

Influence factors |

Brief description |

Authority |

People follow directions when it is thought they come from someone in charge. |

Likeability |

Personal liking of the requester leads to a greater likelihood of it being done. |

Reciprocity |

Providing favors creates a sense of obligation and indebtedness in the receiver. |

Consistency |

Behaving in ways that demonstrate one’s beliefs and attitudes positively affects or influences others. |

Social approval |

It is safer to follow the crowd, so showing that what is required is accepted by many others is often sufficient. |

Scarcity |

Value tends to be associated with scarcity, and choices are influenced by this. |

Influence and the Engagement Strategy

In this section, we revisit the modularization of courses at a UK university. We examine the power and influence exerted by the stakeholders, and the strategies adopted by the program management team (see Case 6.4: Modularization at a UK University: The Influence Strategies). The project was stakeholder-sensitive. The vision was set by the management team, but the project faced large numbers of stakeholders who were, at worst, actively negative toward the project, and at best, passively disinterested.

As already mentioned, the new vice-chancellor (head of the university) was selected for his track record in getting things done, and it was thought he would provide the necessary motivational leadership to the university management team.

This type of leadership was necessary as the project was not just about changes to the way the university structured and ran its undergraduate courses, but to address a lack of pride in the university and what it stood for.

The conduct of the modularization program is an example of the planned use of influence power on a grand scale, influence that would change the very culture of the university.

For this program to succeed, it would have to build a decisive coalition between the stakeholders who held power in the organization and would have to isolate those who sought to oppose the new university structure. An analysis of stakeholders using the salience approach showed that some groups, like lecturers, were just too large and diverse to be considered to have homogenous views or to act as a single coherent group. If they were to create a coalition, however, they would have the power of sheer numbers to influence the university by raising the conflict levels around the project.

The management team and deans of faculty, while relatively small in number, also had mixed agendas about the project. While some of the management team were aligned with the vice-chancellor as definitive stakeholders, others not directly affected by the change were dormant. The deans had high power over and on the program and were classified as either dominant or dangerous depending upon the positions they took.

Case 6.4

Modularization at a UK University: The Influence Strategies

The modularization program faced resistance from stakeholders across the organization:

• Lecturers felt they were already overworked and under pressure to show improvements in their research output; they did not want anything else on their plate.

• Academic registry would have to deal with opposition and downright hostility to the re-accreditation of courses.

• Current students, by far the largest group of stakeholders, were unclear as to what was happening and were influenced most by their lecturers.

• Other stakeholders, not directly affected by the change, such as academic computing and library services, watched from the side lines, undecided as to who to support.

Each group had priorities that were quite different from those that would need to be imposed if the program was ever to succeed. The culture of the university did not lend itself to command and control leadership. It was a political environment, which valued expertise and academic achievement rather more than management and administration. Power sources such as expertise and resources were comparable to, if not more important, than positional power. Deans of faculties, particularly successful faculties (high student numbers and notable research), dominated the power hierarchy.

In analyzing the conduct of the stakeholder engagement in this program, we identified five predominant influencing strategies:

• Increase the power of the program management board and the power of the members on it

• Identify faculty-by-faculty quick wins

• Position the aims of the project as good and commonly accepted in the university sector

• Align the university performance scheme with the new approach

• Delivery of organizational communication by familiar faces

In Table 6.5, we have outlined in more detail the actions taken by the program and how they relate to the types of influence and persuasion strategies described earlier.

Table 6.5 Analysis of engagement strategies on Case 6.4

This program was a success because it delivered its vision—a revitalized, united, and proud institution. It also delivered the modularization of its undergraduate courses. The positive impact caused by the creation of stakeholder coalitions and working relationships across departments was critical to the sustained change in practices.

In Summary

Engagement is much more than just communicating with your stakeholders. Effective engagement demands an understanding of the power available to stakeholders and the power and influence strategies that the project can utilize.

• Engagement is a participative process. It implies a willingness to listen to stakeholders, to discuss mutual interests, and to be prepared to modify the direction or the conduct of a project, based upon stakeholder input.

• Engagement must be audience-centric, and it is, therefore, unlikely that a single form of engagement will ever suffice for stakeholders with differing needs and agendas.

• As projects progress, the number and density of the stakeholder network grow. Stakeholder analysis is not just about the relationships between the project and the stakeholders, but also the networks of relationships that exist between stakeholders.

Reflections

1. Consider the steps in meaningful engagement (Jeffery 2009). What actions would you need to take to move toward more meaningful engagement?

2. For your own project, what are the sources of power of the major stakeholders?

3. What influence strategies are you using? Which additional strategies could you use on your projects?