Chapter 2

Doing the Groundwork

In This Chapter

![]() Understanding what a small business is

Understanding what a small business is

![]() Checking whether you’re the business type

Checking whether you’re the business type

![]() Running towards great ideas and avoiding bad ones

Running towards great ideas and avoiding bad ones

![]() Appreciating the impact of the broader economy

Appreciating the impact of the broader economy

![]() Recognising success characteristics

Recognising success characteristics

If you’ve worked in a big organisation, you know that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are different kinds of animal from big businesses. SMEs are more vulnerable to the vagaries of the economy, but are vital to its vigour.

In this chapter, you can find out how to come up with a great business idea and avoid the lemons. You can also look at the most common mistakes that businesses starting up make and how you can avoid them.

Understanding the Small Business Environment

During one of the all too many periods in recent history when the business climate was particularly frigid (the recent global credit crunch being a good example), some bright spark claimed that the only sure-fire way to get a small business safely down the slipway was to start out with a big one and shrink it down to size. I can’t deny that that’s one way to get started, but even as a joke the statement completely misses the point. Small businesses have almost nothing in common with big ones. Just because someone, you perhaps, has worked in a big business, however successfully, that’s no guarantee of success in the small business world.

Big businesses usually have deep pockets, and even if those pockets aren’t actually stuffed full of cash, after years of trading under their belt they can get the ear of their bank manager in all but the most extraordinary of circumstances. Even if unsuccessful at the bank, big firms can generally extract credit from suppliers, especially if the suppliers are smaller and susceptible to being leaned on in order to retain them as a customer. If all else fails, big businesses may have the option to tap their shareholders or go out to the stock market for more boodle – options a small business owner can only dream about. Of course, if the business is huge, in times of extreme hardship it can expect a sympathetic hearing from the government. The UK government shrank from letting Northern Rock fold, the US government threw General Motors a lifeline and France’s Nicholas Sarkozy used public cash to keep Renault and Peugeot Citroën in business so long as they kept their French factories open. The boss of a big firm has legions of staff to carry out research, and to do all those hundred and one boring but essential jobs, like writing up the books, that are essential preludes to tapping into credit.

In contrast, small business founders have to stay up late, burning the midnight oil and poring over those figures themselves. To cap it all, they may even have to get up at dawn and make special deliveries to customers in order to ensure that they meet deadlines. Big business bosses have chauffeurs and travel business class; after all, they don’t own a large proportion of the business’s shares, so however frugal they are, they won’t be much richer. Small firm founders, however, are personally poorer every time an employee makes a phone call at work, books a business trip or takes a client out to lunch, unless that call, trip or lunch generates extra business. The question that separates owners from employees (which is, after all, what bosses of big businesses really are, however powerful they look from below) is: if it was your money, would you spend it on that call, business trip or lunch? Seven times out of ten the answer is, ‘No way, not with my dosh.’

Defining Small Business

Small business defies easy definition. Typically, people apply the term small business to one-man bands such as shops, garages and restaurants, and apply the term big business to such giants as IBM, General Motors, Shell and Microsoft. But between these two extremes fall businesses that you may look upon as big or small, depending on the yardstick and cut-off point you use to measure size.

No single definition exists of a small firm, mainly because of the wide diversity of businesses. One wit claimed that a business was small if it felt it was, and a grain of truth exists in that point of view.

In practical terms the only reason to be concerned about a business’s size, age or business sector is the support and constraints imposed by virtue of those factors. The government, for example, may offer grant aid, support or even constraints based on such factors. For instance, a business with a small annual sales turnover, less than £15,000, can file a much simpler set of accounts than a larger business can.

Looking at the Types of People Who Start Businesses

At one level, statistics on small firms are precise. Government collects and analyses the basic data on how many businesses start (and close) in each geographic area and what type of activity those businesses undertake. Periodic studies give further insights into how new and small firms are financed or how much of their business comes from overseas markets. Beyond that the ‘facts’ become a little more hazy and information comes most often from informal studies by banks, academics and others who may have a particular axe to grind.

The first fact about the UK small business sector is how big it is. Over 4.8 million people now run their own business, up from 1.9 million three decades ago.

The desire to start a business isn’t evenly distributed across the population as a whole. Certain factors such as geographic area and age group seem to influence the number of start-ups at any one time. The following sections explore some of these factors.

Making your age an asset

Research by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (www.gemconsortium.org) and the UK Office for National Statistics (www.statistics.gov.uk) reveals a number of interesting facts about the age of small business starters:

- Every age group from 18 through to 64 is represented in the business starter population.

- Between 6 and 9 per cent of each age group run their own businesses.

- The youngest age group (16–24), particularly in Scotland and Wales, is now among the most likely to be running a business. The reason may be the high levels of youth unemployment and a decline in opportunities for graduates.

- The older age group (55–64) is seeing a surge in interest from people wanting to keep at work after leaving employment. (In the US, this group has the highest rate of entrepreneurship, and people over 55 are almost twice as likely to found successful companies than those between 20 and 34.)

Zandra Johnson, 67, launched her company Fairy Tale Children’s Furniture, making bespoke furniture for children, five years ago. Her start-up capital was £12,000 saved up over a decade while working in the voluntary sector. With no business experience, she augmented her skills by attending business courses and seminars and reading copiously. By 2013, her website (www.fairytalechildrensfurniture.co.uk) was packed full of products.

Zandra Johnson, 67, launched her company Fairy Tale Children’s Furniture, making bespoke furniture for children, five years ago. Her start-up capital was £12,000 saved up over a decade while working in the voluntary sector. With no business experience, she augmented her skills by attending business courses and seminars and reading copiously. By 2013, her website (www.fairytalechildrensfurniture.co.uk) was packed full of products.

Considering location

More than three times as many people in London start a business as do those in the North East of England. So, at the very least you’re more likely to feel lonelier as an entrepreneur in that area, or in Wales and Scotland, than in, say, London or the South East.

Winning with women

Figures from the Office of National Statistics show that 614,000 women in the UK ran their own business full time in July 2013, a 10.3 per cent increase on the 556,000 a year earlier. Some 2,399,000 men ran their own business full time, a 2.5 per cent drop from the preceding year.

The British Association of Women Entrepreneurs (www.bawe-uk.org) and Everywoman (www.everywoman.com) are useful starting points to find out more about targeted help and advice for women starting up a business.

The types of businesses that women run reflect the pattern of their occupations in employment. The public administration, education and health fields account for around a quarter of self-employed women, and distribution, hotels and restaurants another fifth.

In financing a new business, women tend to prefer using personal credit cards or remortgaging their home, and men prefer bank loan finance and government and local authority grants.

Being educated about education

A popular myth states that under-educated self-made men dominate the field of entrepreneurship. Anecdotal evidence seems to throw up enough examples of school or university drop-outs to support the theory that education is unnecessary, perhaps even a hindrance, to getting a business started. After all, if Sir Richard Branson (Virgin) dropped out of full-time education at 16, and Lord Sugar (Amstrad), Sir Philip Green (BHS and Arcadia, the group that includes Topshop and Miss Selfridge), Sir Bernie Ecclestone (Formula One – Britain’s tenth richest man) and Charles Dunstone (Carphone Warehouse) all gave higher education a miss, education can’t be that vital.

However, the facts, such as they are, reveal a rather different picture. Research shows that the more educated the population, the more entrepreneurship takes place. Educated individuals are more likely to identify gaps in the market or understand new technologies. After all, Stelios Haji-Iannou, founder of easyJet, has six degrees to his name, albeit four are honorary. Tony Wheeler, who – together with his wife Maureen – founded Lonely Planet Publications, has degrees from Warwick University and the London Business School. Jeff Bezos (Amazon) is an alumnus of Princeton, and Google’s founders, Sergey Brin and Larry Page, graduated from Stanford.

So if you’re in education now, stay the course. After all, a key characteristic of successful business starters is persistence and the ability to see things through to completion. Chapter 3 outlines more entrepreneurial attributes.

Coming Up with a Winning Idea

Every business starts with the germ of an idea. The idea may stem from nothing more profound than a feeling that customers are getting a raw deal from their present suppliers.

In this section, you can find out tried-and-tested ways to help you come up with a great idea for a new business.

Ranking popular start-up ideas

The government’s statistics service produces periodic statistics on the types of businesses operating in the UK.

Table 2-1 Businesses Operating by Sector, 2012

|

Sector |

Total |

|

Construction |

907,480 |

|

Wholesale and retail trade; repairs |

514,805 |

|

Admin and support service |

378,735 |

|

Human health and social work |

303,540 |

|

Information and communication |

289,075 |

|

Transportation and storage |

269,945 |

|

Education |

243,220 |

|

Manufacturing |

230,970 |

|

Arts, entertainment and recreation |

209,430 |

|

Accommodation and food service |

166,555 |

|

Agriculture, forestry and fishing |

152,085 |

|

Real estate |

91,810 |

|

Finance and insurance |

76,380 |

You can take one of two views on entering a particularly popular business sector: it represents a great idea you’re mad to resist, or the business is already awash with competition. In practice, the best view to take is that if others are starting up, at least a market opportunity exists. Your task is to research the market thoroughly, using Chapter 4 as your guide.

Going with fast growth

Entrepreneur.com produces an annual list of hot business sectors to enter (www.entrepreneur.com/article/224977). The 2013 list includes:

- Beauty: When it comes to anti-aging solutions, beauty seekers are in favour of ‘cosmeceuticals’, personal-care products with supposed skin-enhancing ingredients. Growth is driven by products advertising ‘active and natural’ ingredients like rice-enzyme powders and rainforest plant extracts.

- Education: The lack of jobs has sent millions around the globe back to college to train or retrain. Universities in the UK are full to bursting point. Unsurprisingly, a boom is occurring in online learning, tutoring and other private learning facilities.

- Energy-enhancing products: Red Bull started the trend. Launched in 1987 in Austria, it didn’t hit the USA and mainstream Europe until 1997, but since then Red Bull and other energy-enhancing products have grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry fuelled by young consumers.

- Green energy and renewables: A growing sector because governments the world over are chucking what little money they have at this.

- Senior market: With the population of over-64s exploding, this sector is a no-brainer to serve. Academics, always quick to latch on to opportunities, have singled out gerontology (the study of social, psychological and biological aspects of aging with the view of extending active life while enhancing its quality) as a hot area, and a university is scheduled to debut a new master’s degree in aging-services management to meet the growing interest in the field.

You can use this information to help pick a fast-growing business area to start your business in. Beginning with the current flowing strongly in the direction you want to travel can make things easier for you from the start.

Spotting a gap in the market

The classic way to identify a great opportunity is to see something that people would buy if only they knew about it. The demand is latent, lying beneath the surface, waiting for someone – you, hopefully – to recognise that the market is crying out for something no one is yet supplying.

The following are some of the ways to go about identifying a market gap:

- Adapting: Can you take an idea that’s already working in another part of the country or abroad and bring it to your own market?

- Locating: Do customers have to travel too far to reach their present source of supply? This situation is a classic route to market for shops, hairdressers and other retail-based businesses, including those that can benefit from online fulfilment.

- Size: If you made things a different size, would that appeal to a new market? Anita Roddick of The Body Shop found that she could only buy the beauty products she wanted in huge quantities. By breaking down the quantities and sizes of those products and selling them, she unleashed a huge new demand.

- Timing: Are customers happy with current opening hours? If you opened later, earlier or longer, would you tap into a new market?

Revamping an old idea

A good starting point is to look for products or services that used to work really well, but have stopped selling. Ask yourself why they seem to have died out and then try to establish whether, and how, you can overcome that problem. Or you can search overseas or in other markets for products and services that have worked well for years in their home markets but have so far failed to penetrate into your area.

Sometimes with little more than a slight adjustment you can give an old idea a whole new lease of life. For example, the Monopoly game, with its emphasis on the universal appeal of London street names, has been launched in France with Parisian rues and in Cornwall using towns rather than streets.

Using the Internet

Many of the first generation of Internet start-ups had nothing unique about their offer – the mere fact that the business was ‘on the net’ was thought to be enough. Hardly surprisingly, most of them went belly-up in no time at all.

However, you also need something about the way you use the Internet to add extra value over and above the traditional ways in which your product or service is sold. Online employment agencies, for example, can add value to their websites by offering clients and applicants useful information such as interview tips, prevailing wage rates and employment law updates.

But using the Internet to take an old idea and turn it into a new and more cost-efficient business can be a winner. Check out the example in the ‘Winning on the net’ sidebar. Chapter 15 is devoted exclusively to the subject of making a success of getting online and making money.

Solving customer problems

Sometimes existing suppliers just aren’t meeting customers’ needs. Big firms often don’t have the time to pay attention to all their customers properly because doing so just isn’t economic. Recognising that enough people exist with needs and expectations that aren’t being met can constitute an opportunity for a new small firm to start up.

Start by recalling the occasions when you’ve had reason to complain about a product or service. You can extend that by canvassing the experiences of friends, relatives and colleagues. If you spot a recurring complaint, that may be a valuable clue about a problem just waiting to be solved.

Next, go back over the times when firms you’ve tried to deal with have put restrictions or barriers in the way of your purchase. If those restrictions seem easy to overcome, and others share your experience, then you may well be on the trail of a new business idea.

Creating inventions and innovations

Inventions and innovations are all too often almost the opposite of identifying a gap in the market or solving an unsolved problem. Inventors usually start by looking through the other end of the telescope. They find an interesting problem and solve it. There may or may not be a great need for whatever it is they invent.

The Post-it note is a good example of inventors going out on a limb to satisfy themselves rather than to meet a particular need or even solve a burning problem. The story goes that scientists at 3M, a giant American company, came across an adhesive that failed most of their tests. It had poor adhesion qualities because it could be separated from anything it was stuck to. No obvious market existed, but they persevered and pushed the product on their marketing department, saying that the new product had unique properties in that it stuck ‘permanently, but temporarily’. The rest, as they say, is history.

Marketing other people’s ideas

You may not have a business idea of your own, but nevertheless feel strongly that you want to work for yourself. This approach isn’t unusual. Sometimes an event such as redundancy, early retirement or a financial windfall prompts you to searching for a business idea.

Business ideas often come from the knowledge and experience gained in previous jobs, but take time to come into focus. Usually, you need a good flow of ideas before one arrives that appeals to you and appears viable.

- Browse websites. The Internet is a great source of business ideas. Try Entrepreneurs.com (www.entrepreneur.com/bizopportunities), which lists hundreds of ideas for new businesses, together with information on start-up costs and suggestions for further research. It also has a series of checklists to help you evaluate a business opportunity to see whether it’s right for you. Home Working (www.homeworkinguk.com) lists dozens of current business ideas exclusively aimed at the British market.

- Read business magazines. Periodicals such as Start Your Business magazine (www.startyourbusinessmag.com) present the bones of a number of ideas each month.

- Scan papers and periodicals. Almost all papers and many general magazines too have sections on opportunities and ideas for small businesses.

The ASA (www.asa.org.uk) publishes a quarterly list of complaints that it has considered or is investigating. Also check out websites such as www.scambusters.org, www.scam.com and www.fraudguides.com, which track the latest wheezes doing the rounds both on- and offline.

Being better or different

To have any realistic hope of success, every business opportunity must pass one crucial test: the idea or the way the business is to operate must be different from or better than any other business in the same line of work. In other words you need a unique selling proposition (USP), or its Internet equivalent, a killer application.

The thinking behind these two propositions is that your business should have a near-unbeatable competitive advantage if your product or service offers something highly desirable that others in the field can’t easily copy: something that only you can offer. Dyson’s initial USP was the bagless cleaner, and Amazon’s was ‘one-click’ shopping, a system for retaining customer details that made buying online a less painful experience.

The trick with USPs and killer applications doesn’t just lie with developing the idea in the first place, but making it difficult for others to copy it. (Chapter 5 suggests ways to protect your USP.)

If neither you nor the product or service you’re offering stands out in some way, why on earth would anyone want to buy from you? But don’t run off with the idea that only new inventions have any hope of success. Often just doing what you say you’ll do, when you say you’ll do it, is enough to make you stand out from the crowd.

I point out ways to test the feasibility of your business idea in Chapter 4.

Finding a contract in the public sector

However tough the economic climate, one sector of customers is always buying: the public sector. Roads have to be built, hospitals run, soldiers armed and legislation extended and enforced. The government invests a lot of money, and is eager to encourage small, new and owner-managed firms to grab a slice of the action.

Banning Bad Reasons to Start a Business

You may have any number of good reasons to start a business, but make sure that you’re not starting a business for the wrong reasons – some of which I explore in the following sections.

Steering clear of bad assumptions

You need to be sure that your business idea isn’t a lemon. You can’t be sure that you’ve a winning idea on your hands, but you can take steps to make sure that you avoid obvious losers. Much as you want to start a business, don’t get in over your head because you start from a bad premise, such as those in the following list:

- The market needs educating. You may think that you have a situation in which the market doesn’t yet realise it can’t live without your product or service. Many early Internet businesses fitted this description and look what happened to them. If you think that customers have to be educated before they purchase your product, walk away from the idea and leave it to people with deep pockets and a long-time horizon; they’ll need them.

- We’re first to market. Gaining ‘first-mover advantage’ is a concept used to justify a headlong rush into a new business, but as I explain in Chapter 1, the idea is probably incorrect.

- If we can get just 1 per cent of the market, we’re on to a winner. No markets exist with a vacant percentage or two just waiting to be filled. Entering almost any market involves displacing someone else, even if your product is new. Po Na Na, a chain of late-night souk bars, failed despite being new and apparently without competitors. If the company had captured just 1 per cent of the dining market instead of 100 per cent of the souk-eating student market, it may have survived. But the dining market had Italian, Indian, Greek and French competitors already in place. This, when combined with the vastly improved range of ready-to-eat meals from the supermarket, means that companies fight bitterly over every hundredth of a per cent of this market.

Every business begins with an idea, but it doesn’t necessarily have to be your own idea. It has to be a viable idea, which means that the market has to contain customers who want to buy from you. And enough of them have to exist to make you the kind of living you want. It may be an idea that you’ve nursed and investigated for years, or it may be someone else’s great idea that’s just too big for her to exploit on her own. A franchised business is one example of a business idea that has room for more than one would-be business starter to get involved. Franchises can be run at many levels, ranging from simply taking up a local franchise, through to running a small chain of two to five such franchises covering neighbouring areas.

Avoiding obvious mistakes

Your enthusiasm for starting a business is a valuable asset as long as you don’t let it blind you to practical realities. The following list contains some reasoning to resist.

- Starting in a business sector of which you’ve little or no previous knowledge or experience. The grass always looks greener, making business opportunities in distant lands or in technologies with which you’ve only a passing acquaintance seem disproportionately attractive. Taking this route leads to disaster. Success in business depends on superior market knowledge from the outset and sustaining that knowledge in the face of relentless competition.

- Putting in more money than you can afford to lose, especially if you have to pay upfront. You need time to find out how business works. If you’ve spent all your capital and exhausted your capacity for credit on the first spin of the wheel, you’re more of a gambler than an entrepreneur. The true entrepreneur takes only a calculated risk. Freddie Laker, who started the first low-cost, no-frills airline, bet everything he could raise on buying more planes than he could afford. To compound the risk, he bet against the exchange rate between the pound and the dollar – and lost. Learn from Mr Laker’s mistake.

- Pitting yourself against established businesses before you’re strong enough to resist them. Laker also broke the third taboo: he took on the big boys on their own ground. He upset the British and American national carriers on their most lucrative routes. There was no way that big, entrenched businesses with deep pockets would yield territory to a newcomer without a fight to the death. That’s not to say that Laker’s business model was wrong. After all, Ryanair and easyJet have proved that it can work. But those businesses tackled the short-haul market to and from new airfields and, in the case of easyJet, at least started out with tens of millions of pounds of family money that came from a lifetime in the transportation business.

Recognising that the Economy Matters

The state of the economy in general has an effect both on the propensity of people to start a business and on their chances of survival. Although business cycles have no doubt been in existence for centuries, a serious study of the subject is barely 150 years old. Joseph Schumpeter, the American economist who more or less invented the subject of economics, defined the cycle itself as ‘the economic ebb and flow that defines capitalism’. ‘Cycles,’ he wrote, ‘are not, like tonsils, separable things that might be treated by themselves, but are, like the beat of the heart, of the essence of the organism that displays them.’ In a later work, he went on to claim that business enterprises operate in ‘the perennial gale of creative destruction’. This creative destruction – the term for which Schumpeter is perhaps best remembered – is the by-product of the continuous stream of innovation; the more radical the innovation – steam, electricity, the Internet – the more violent the cycle.

Spotting cycles

Seeing a business cycle on the horizon would be a doddle if there weren’t so many of them and they weren’t all so different! At least four competing, overlapping and even contradictory theories exist about the shape and form of business cycles, including:

- The Juglar Cycle, named after Clement Juglar, a French economist who studied interest rate and price changes in the 1860s and observed boom and bust waves of 9 to 11 years going through four phases in each cycle:

- Prosperity: Where investors rush into new and exciting ventures.

- Crisis: When business failure rates start to rise.

- Liquidation: When investors pull out of markets.

- Recession: When the consequences of these failures begin to be felt in the wider economy in terms of job losses and reduced consumption.

- The Kitchin Cycle, also known as the inventory cycle, named after Joseph Kitchin who discovered a 40-month cycle resulting from a study of US and UK statistics from 1890 to 1922. When demand appears to be stronger than it really is, companies build and carry too much inventory, leading people to overestimate likely future growth. When that higher growth fails to materialise, inventories are reduced, often sharply, so inflicting a ‘boom, bust’ pressure on the economy.

- Kondratieff’s theory was that the advent of capitalism had created long-wave economic cycles lasting around 50 years. His theories received a boost when the Great Depression (1929–1933) hit world economies. The idea of a long wave is supported by evidence that major enabling technologies, from the first printing press to the Internet, take 50 years to yield full value, before themselves being overtaken.

- Kuznet’s Cycle, proposed by Simon Kuznet, is based around the proposition that it takes 15 to 25 years to acquire land, get the necessary permissions, build property and sell. Also known as the building cycle, this theory has credibility because so much of economic life is influenced by property and the related purchases of furniture and associated professional charges, for example for lawyers, architects and surveyors.

Readying for the ups and downs

Clearly, it would be helpful if a business starter could have warning in advance about the likelihood of a downturn. In much the same way as a shipping forecast helps sailors trim their boats before a storm, some advance warning would let businesses do the same. Sailors don’t need to have a detailed knowledge of what causes tides, currents and winds, just an indication of when a change is likely to occur and how serious and prolonged the event will be. Information on the timing, strength, shape and path of the downturn stage of an economic cycle would help managers.

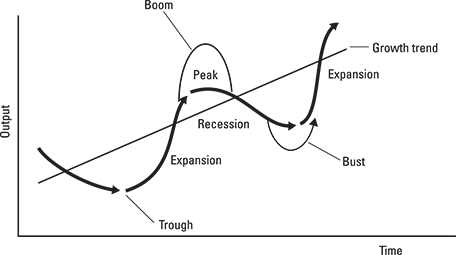

People generally understand and recognise the broad shape of the effect of the economic cycle on output: in other words, total demand for goods and services (see Figure 2-1). But a few caveats to this pattern exist. A double dip can occur with two downturns before recovery gets properly underway, and occasionally long periods of flat-lining can occur, where the economy virtually stands still, neither growing nor contracting.

Figure 2-1: Typical path of an economic cycle.

Unfortunately, no one has yet come up with a reliable way of anticipating the turning points in cycles. Only two economists, Friedrich von Hayek and Ludwig von Mises, forecasted the stock market crash of 1929. The Harvard Economics Society concluded in November after the 1929 crash that ‘a depression seems improbable; we expect a recovery of business next spring with further improvements in the fall’. In fact, the Society was to dissolve itself before the depression was halfway through its life. ‘All economic cycles are easy to predict, apart from the one you’re in’ is the helpful guidance on offer from most academic economists.

Maynard Keynes, the famous British economist, described the cause of the violent and unpredictable nature of the business cycle as ‘animal spirits’, or people’s tendency to let emotions, particularly swings from excessive optimism to excessive pessimism, influence their economic actions. In short, the business cycle is all down to how millions of people feel!

Two schools of thought exist on whether starting a business is more difficult when the economy is contracting, corresponding to whether you subscribe to the belief that a glass is half full or half empty. On the one hand, fewer competitors are in the market, because many have failed. But on the other hand, those remaining are both seasoned warriors and more desperate to keep what small amount of business exists to themselves.

Most people start a business when they want to and not at a favourable stage in the economic cycle. That, however, doesn’t mean that you can simply ignore the economy. In much the same way as a prudent sailor pays attention to the state of the tide, you need to see whether the general trend of the economy is working with or against you.

Preparing to Recognise Success

To be truly successful in running your own business, you have to both make money and have fun. That’s your pay-off for the long hours, the pressure of meeting tough deadlines and the constant stream of problems that accompany most start-up ventures.

One measure of success for any business is just staying in business. That’s not as trite a goal as it sounds, nor is it easily achieved, as you can see by looking at the number of businesses that fail each year. However, survival isn’t enough. Cash flow, which I look at in Chapter 8, is the key to survival, but becoming profitable and making worthwhile use of the assets you employ determine whether staying in business is worth all your hard work.

Measuring business success

No one in their right mind sets out to run an unsuccessful business, although that’s exactly what millions of business founders end up doing. Answering the following questions can act as a check on your progress and keep you on track to success.

- Are you meeting your goals and objectives? In Chapter 6 I talk about setting down business goals. Achieving those goals and objectives is both motivational and, ultimately, the reason you’re in business.

- Are you making enough money? This question may sound daft, but it may well be the most important one you ask. The answer comes out of your reply to two subsidiary questions:

- Can you do better by investing your time and money elsewhere? If the answer to this question is yes, go back to the drawing board with your business idea.

- Can you make enough money to invest in growing your business? The answer to this question only becomes clear when you work out your profit margins, which I cover in Chapter 13. But the fact that many businesses don’t make enough money to reinvest in themselves is pretty evident when you see scruffy, run-down premises, worn-out equipment and the like.

- Can you work to your values? Anita Roddick’s Body Shop had a clearly articulated set of values that she and every employee bought into. Every aspect of the business, from product and market development down to the recruitment process, promoted this value system – if you weren’t green, you didn’t join. Ms Roddick’s philosophy may have been a little higher than you feel like going, but values can help guide you and your team when the going gets tough.

Exploring the myth and reality of business survival rates

Misinformation continually circulates about the number of failing businesses. The most persistent and wrong statistic is that 70 per cent (some quote 90 per cent) of all new businesses fail. The failure rate is high, but not that high. And in any case the term failure itself, if people use the word to mean a business closing down, has a number of subtly different nuances.

Millions of small businesses start up, but many survive for a relatively short time. Over half of all independently owned ventures cease trading within five years of starting up. However, if you can make it for five years, the chances of your business surviving increase dramatically from earlier years.

The Office of the Official Receiver lists the following causes for business failures:

- Bad debts: Unfortunately, having great products and services and customers keen to buy them is only half the problem. The other half is making sure that those customers pay up on time. One or two late or non-payers can kill off a start-up venture. In Chapter 13, you can find strategies to make sure that you get paid and aren’t left in the lurch.

- Competition: Without a sound strategy for winning and retaining customers, your business is at the mercy of the competition. In Chapter 10, you can discover how to win the battle for the customer.

- Excessive remuneration to the owners: Some business owners mistake the cash coming into the business for profit and take that money out as drawings. They forget that they have to allow for periodic bills for tax, value added tax (VAT), insurance and replacement equipment before they can calculate the true profit, and hence what they can safely draw out of the business. In Chapter 13 you can discover how to tell profit from cash and how to allow for future bills.

- Insufficient turnover: This situation can occur if the fixed costs of your business are too high for the level of sales turnover achieved. Chapter 13 shows how to calculate your break-even point and so keep sales levels sufficient to remain profitable.

- Lack of proper accounting: Often business founders are too busy in the start-up phase to keep track of the figures. They pile up invoices and bills to await a convenient moment when they can enter these figures in the accounts. However, without timely financial information, you may miss key signals or make wrong decisions. In Chapter 13, you can read about how to keep on top of the numbers.

- Not enough capital: You, along with most business start-ups, may hope to get going on a shoestring. But you need to be realistic about how much cash you need to get underway and stay in business until sales volumes build up. In Chapter 8, you can see how to plan your cash flow so that you can survive.

- Poor management and supervision: You may well know how your business works, but sharing that knowledge and expertise with those you employ isn’t always that easy. In Chapter 11, you see how to manage, control and get the best employees to give of their best.

According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the chances of your business surviving are best in Northern Ireland, where just over 70 per cent are still going after three years, and worst in London, where around 60 per cent of businesses remain after three years.

According to the UK Office for National Statistics, the chances of your business surviving are best in Northern Ireland, where just over 70 per cent are still going after three years, and worst in London, where around 60 per cent of businesses remain after three years. Select Database, a direct marketing firm, has a nifty database that can tell you how many businesses have been set up recently in any postal district in the UK (

Select Database, a direct marketing firm, has a nifty database that can tell you how many businesses have been set up recently in any postal district in the UK ( Self-employment, a term used interchangeably with starting a business, tends to be a mid-life choice for women, with the majority starting up businesses after the age of 35. Self-employed women usually have children at home (kudos to these super-mums), and many go the self-employment route because they have family commitments. In most cases, self-employment grants greater schedule flexibility than the rigors of a nine-to-five job.

Self-employment, a term used interchangeably with starting a business, tends to be a mid-life choice for women, with the majority starting up businesses after the age of 35. Self-employed women usually have children at home (kudos to these super-mums), and many go the self-employment route because they have family commitments. In most cases, self-employment grants greater schedule flexibility than the rigors of a nine-to-five job. Never go down the lonely inventor’s route without getting plenty of help and advice. Chapter

Never go down the lonely inventor’s route without getting plenty of help and advice. Chapter  If you’ve a choice of when to start up, having the current working for you is usually better than having it against you, so choose to open your business during an economic upswing, if possible.

If you’ve a choice of when to start up, having the current working for you is usually better than having it against you, so choose to open your business during an economic upswing, if possible.