Open Debate and Interviews with Movie Industry Professionals

Open Debate

The profile that emerges from the technical description of the Steadicam and an examination of some films on which it was used is of a useful and versatile device. The Steadicam, besides giving the operator freedom of movement, in almost all situations, also frees the actors. In fact, no longer constrained by dolly tracks or other structures, the actors move freely over the whole area of the action.

Bertrand Tavernier chose to use this device precisely for its capacity to follow the actor without limiting his actions: ‘I wanted to use it to give a great liberty to the actors, to be able to go everywhere without seeming to do so, to shoot very long takes’.1

Giuseppe Rotunno, instead, finds that the same effects can be obtained with a good hand-held camera (and other means) and that, indeed, the abuse of this tool leads to sterility in the construction of stories: ‘I think that a lot of what is done with the Steadicam is an escape, especially if the director doesn’t know what to do and so, thinking he’ll give the scene more weight, he takes the Steadicam and goes’.2

Ed DiGiulio sees the Steadicam as an extension of the operator: ‘by supporting the total weight of the camera system from the body brace we permit the camera to move with the operator as if it were an extension of its own body (part of its internal servosystem, so to speak) so the operator can easily control and guide the camera in any direction he pleases with a gentle movement of his hand’.3

For M. Chion, this extension of the body represents a hybrid between technique and person that it might not be possible to tame: ‘Actually, the Steadicam is really a ‘cyborg’ device, a combination of man and machine, of muscle and mechanics as Boorman said – and the risk is that with such a device you don’t feel … either the one or the other: neither the muscle’s tension, nor the machine’s precision’.4

The argument which developed between Chion and Tavernier in the pages of Cahiers du Cinema is interesting for Chion’s assertions emphasizing the obvious and at times imprecise use of the Steadicam in Coup de Torchon: ‘The moves and the shots of Glenn’s camera are quite variable, unsteady, at times almost dancing’.5 Chion makes a comparison between The Shining and Coup de Torchon, as two of the first movies to use the Steadicam. While the first uses to advantage the spectacular characteristics of the device during the chases down the hallways, done with great precision, the second on the other hand, uses unstable camera moves and follows the characters ‘awkwardly’. Actually, for Tavernier this is a desirable effect that helps the construction of the film: ‘The Steadicam gave me a style of ‘mise en scene’ that continually led people into the ‘scene’ and tracked the characters as they looked at themselves, observed themselves … Also it gave me great freedom of movement’. The argument continues with an article by Tavernier in which he maintains that he never ‘used the Steadicam that much’ and a further reply by Chion: ‘In a work, it isn’t the frequency of a ‘method’ or a form that counts; it’s the way in which it defines the style. For their particularity and their presence at significant moments, Coup de Torchon is marked by its Steadicam sequences.6

Some ‘good sense’ regarding the use of this device, and whether it indeed determines how a story will be told, is provided by Garrett Brown: ‘Steadicam doesn’t ever determine story but offers some storytelling possibilities that permit more flexible and longer takes, if there is reason to continue uncut. Of course it’s a tool, frequently badly used like every tool, sometimes used in a manner to charm the gods’.7

Interviews

This final portion of the book contains a series of interviews with people who work in the movie industry. They generously expressed their opinions, told their stories, recalled anecdotes and experiences regarding the invention and the use of the Steadicam. These interviews enrich our knowledge of the Steadicam (past and present) by giving us the direct testimony of camera operators, Directors of Photography, and movie directors.

It is interesting to note the different approaches and points of view, the various criticisms and observations which, taken together, communicate a great passion for cinema, movie making and the constant creative invention which very often involves and stimulates technique.

I would like to thank each person interviewed for their kindness in giving of their time: Garrett Brown, Giuseppe Rotunno, John Carpenter, Mario Orfini, Larry McConkey, Nicola Pecorini, Haskell Wexler, Ed DiGiulio, Vittorio Storaro and Caroline Goodall.

Interview with Garrett Brown (by E-mail, January 1997)

What are the principal technical characteristics of the Steadicam?

Invention of Steadicam needs four things: a) expanded masses; b) angular isolation (with gimbal); c) spatial isolation (with spring-loaded arm that mimics a human arm); d) a method of viewfinding that doesn’t need the eye on the camera (such as a video monitor).

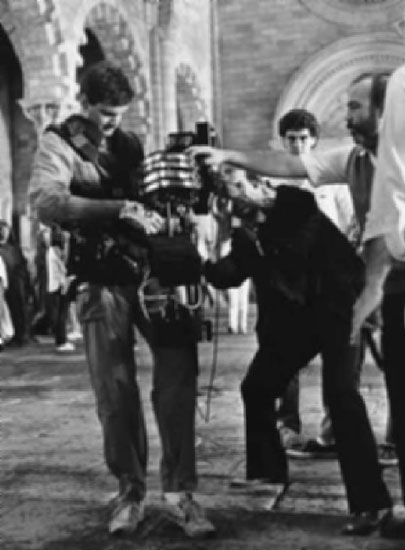

Figure 4.1 Workshop run by Steadicam inventor Garrett Brown during the festival ‘Una città per il Cinema’. Photo: Istituto Cinematografico ‘La Lanterna Magica’, L’Aquila Collection, 1982

Is it difficult to use the Steadicam?

Yes, it takes a workshop, then practice, practice – it’s an instrument.

Do you think that the fact that the vision you have in the Steadicam monitor (viewfinder) is so far from the body (as opposed to an ordinary camera where the viewfinder is near your eye) means that you frame the shot in a different way?

I prefer framing with the Steadicam monitor because I am used to it. Perhaps it’s a more objective look than a viewfinder, particularly for violent action.

Is there a link between the choice of the shot and the kind of tool utilized? I mean, are the Steadicam’s characteristics better suited to certain kinds of shots?

Yes – with overlap, of course, each tool is best for certain shots. Steadicam can stand still and look just like a tripod, but unless you intend to move before or after, what’s the point? My favourite kind of Steadicam shot is when it is used just like a dolly (see next answer).

What do you think about the point of view shot, seeing with the character’s eyes?

I have studied point of view shots. My favourites are with Steadicam – I don’t like hand-held point of views, because I think of the frame as a window and I don’t like my window shaking.

Has Steadicam changed the way films are made or is it only a tool?

The process of filming has changed with Steadicam, but only because some new things are possible and some other things are easier. Each successful tool has this effect on the business aspect, as well as on the creative aspect, of filmmaking.

What are the most important and significant movies in which you used the Steadicam?

Out of nearly 200 movies, The Shining was the most significant for Steadicam use.

Do you find that today the search for content is lacking because it is easier to fill the eyes of the viewer with special effects (such as unbelievable escapes)?

I have the same requirement of special effects as for stunts or regular shots: absolute believability and appropriateness. Otherwise they are not very interesting.

When you thought up this tool, did you imagine something that could approximate human vision?

Yes … and I was looking for a fast-running stunt camera. Only later did I realize that it could be great, therefore didn’t know what it was good for.

What were the first movies to utilize the Steadicam, up to about 1985?

Bound for Glory, Marathon Man, Rocky were all shot during 1975. Some others, at least up through the 1980s, are: Rocky II, The Shining, True Confessions, Greystoke, Falling in Love, Sweet Liberty, Fame, Taps, Prince of the City, Xanadu, Baby It’s You, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom.

Have you used the Steadicam in other fields such as TV, theatre, dance, video?

Yes, except theatre. Others have, but not me personally.

Do you think that this tool is more about the sense of movement and capturing it?

It is about placing the lens where you want it, and moving it to where you want it next, in the manner that you want to move.

When you invent something like the Steadicam or the Skycam are you answering someone’s particular requirements?

I invent for myself first – usually because I want one!

Do you think that the use of Steadicam is linked exclusively with a particular genre of movies?

No!

Have there have been situations in which the use of Steadicam was less successful than using dolly and crane together?

Of course. It is just a tool – frequently badly used like every tool. Sometimes used ‘in a manner to charm the gods’.

What do you think about camera moves using dolly, crane, zoom – the possibilities and limits?

I love camera movement – some of it historically has been influenced by the limitations of dolly and crane, now we have a better, full spectrum of tools, and now it is less likely that one would be forced into an arbitrary style of movement because, for example, the Steadicam didn’t exist.

How much does the Steadicam determine the story and the way it is told?

Steadicam doesn’t ever determine the story, but offers some storytelling possibilities that permit more flexible and longer takes, if there is reason to continue uncut. It also permits more sophisticated camera movement in three dimensions – French curves, etc., rather that straight ahead over the dolly rails.

The Steadicam has speeded up a number of situations that would otherwise be impossible or very expensive. Do you think that this speed can cause contents and lighting to receive less attention?

Yes, sometimes. There have been some atrocities because Steadicam is so facile. It’s regrettable. One could think of easy analogies: the invention of the tripod meant cameras didn’t have to be placed on piled up furniture, and this extra speed may have caused some sloppy work!

What are the difficulties involved in lighting a scene that uses the Steadicam?

Being able to see in all directions during the course of a long shot has required the perfection of some particular lighting techniques: adroit dimmer work, etc., to keep the hot side always as backlight, etc.

Garrett Brown, Steadicam Inventor

Garrett Brown began by making TV commercials and opted for movies after he invented the Steadicam camera stabilizer in 1974. During his prolific career he has shot nearly 200 movies with the Steadicam, and invented a series of extraordinary tools for shooting movies, television, sports events and concerts. Garrett currently holds fifty patents worldwide for camera devices, including the Steadicam JR for camcorders; Skycam, which flies on wires over sporting events; Mobycam, the underwater camera; the Go.cam and the Fly.cam, miniature tracking cameras, and the Emmy award-winning Dive.cam.

He has worked steadily to perfect the quality of his inventions and increase their capacity to shoot under the most difficult conditions.

He shared an Oscar (Class I Award) with Cinema Products in April, 1978 for the invention and development of the Steadicam, as well as winning an Emmy in 1989.

Garrett Brown is a member of the American Society of Cinematographers, the Directors Guild, the Screen Actors Guild and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. He also organizes and teaches Steadicam workshops all over the world.

Films

Some of the films on which he worked are: Bound for Glory, H. Ashby (1976); Marathon Man, J. Schlesinger (1976); Rocky, J. Avildsen (1976); Exorcist II: The Heretic, J. Boorman (1977); Rocky II, S. Stallone (1979); Kramer vs. Kramer, R. Benton (1979); The Shining, S. Kubrick (1980); Fame, A. Parker (1980); The Formula, J. Avildsen (1980); True Confessions, U. Grosbard (1981); Reds, W. Beatty (1981); Taps, H. Becker (1981); Wolfen, M. Wadleigh (1981); Tootsie, S. Pollack (1982); Greystoke – The Legend of Tarzan Lord of the Apes, H. Hudson (1984); Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, S. Spielberg (1984); Legal Eagles, I. Reitman (1986); Rocky V, J. Avildsen (1990); Philadelphia, J. Demme (1993); The Return of the Jedi, R. Marquand (1993); Wolf, M. Nichols (1994); Casino, M. Scorsese (1995); Bullworth, W. Beatty (1998/99); Bringing out the Dead, M. Scorsese (1999).

Interview with Giuseppe Rotunno, Rome, February, 1997

Preface by Giuseppe Rotunno

The Steadicam is a mechanical device like many others: in other words, great movies have been made without the Steadicam. The Steadicam hasn’t resolved the problem of movies, because, in a certain sense it has always existed, people had started to think of the Steadicam a long time ago. I mean to say, we Italians have always used the hand-held camera, even when the Steadicam didn’t exist yet, it’s just that we never made a show of it. I mean no one ever thought about it, but I think every Italian movie has a part that was done with the hand-held camera.

Finally, I think that all technical devices are useful and very important, including the Steadicam, if they help us to tell the story, if they help us to stay within the story. However, I’m completely against the possibility of a movie being conceived for the Steadicam, as if you had to conceive a movie for a camera car or any other device outside the story. The Steadicam, overall, is very important if it is used with awareness of the reason for using it, in other words, if it helps to tell the story.

It is exactly, and only, a device.

How do you choose a camera move?

As is needed. In other words, you must never forget that in a certain sense the camera is the moviegoer, so you can’t take it by the throat and take it around just to take it around. I think that a lot of what is done with the Steadicam is an escape, especially if the director doesn’t know what to do and so, thinking he’ll give the scene more weight, he takes the Steadicam and goes. It’s not like that.

An example of Steadicam that instead is very effective is in Kubrick’s movie The Shining, in which the Steadicam puts the viewer in the position of the characters, suspended in midair; in this case this floating sensation that the Steadicam gives is very effective and perhaps it couldn’t be done with any other device. Even if, for example, with Fellini we did it with the arm of a crane with the camera on it, moving slightly, which is always a good way to give the idea of being suspended in midair, that is to say, detaching the actors from the ground and, obviously, putting the viewer in the same conditions. When all these things meet up, story, technique, lighting and, of course, movement, then it becomes something important.

It happened back in Nouvelle Vague (New Wave) cinema: the people who had serious cinematographic values remained and the others disappeared – the ones who substituted mechanical means for the story, telling just a very limited technical part, forgetting the story. It’s always stories that make history.

Even long shots without cuts have always been done, for that matter – think of Hitchcock’s Rope.

Does there have to be a different kind of lighting for Steadicam movement?

No, lighting has its own particular significance. Lighting too, in my opinion, is part of the story. It can’t be done as a function of the technical device. Above all, it has to be a function of the story. Then it’s the technical means that has to adapt to both the lighting and the story. Overall, there aren’t any technical or emotional, artistic elements in the making of a movie that aren’t part of the story, that aren’t tied to the story. You have to keep in mind that the lens is always the viewer, so you can involve it in the movements if necessary, but this can’t be done haphazardly, it has to be done at the right time, when it’s needed. I cited Kubrick because in that case the thing is explicit, clear.

They say that using the Steadicam saves time; it’s not true. Some movies might use shortcuts of this kind, but the Steadicam is not a time-saving device, because to prepare for that shot, Kubrick took a whole day, sometimes even two days, because he took possession of the means he was using, he didn’t let it take possession of him. In other words, he dominated it. He used it correctly for his story, and this is true for everything in the movies, but particularly for the Steadicam or the hand-held camera (which is the same thing): you can’t abuse it, or try to solve the movie’s, or the story’s, problems with it. With the hand-held camera, the Steadicam, the crane, a free dolly or an idea for a particular shot, everything has to be always a function of the story. That’s my particular point of view and I don’t think it’s only mine.

Is there a relation between Steadicam use and the kinds of films that abuse it?

I think that when we think of the Steadicam we always think of action films, for example, chasing someone up a flight of stairs, which isn’t easy because you need exactly the same amount of time that you need if you’re using an offset arm. In other words, even if you put the camera on a dolly, on an arm, you can follow the person as far as you want to.

There are very, very few cases in which the Steadicam is irreplaceable: for example, if on the stairs you have to cross over and enter another stairwell; but precisely because I want to do something that I can’t do with another device I have to do what serves the purposes of the story. There are the entrances and the exits which can also let you save time and, among other things, you don’t have to go the entire route to tell it cinematographically, you only have to tell a portion of it. In fact, you normally would do just a portion of it to give the movie a better rhythm, to not go on too long.

Now, sometimes instead with the Steadicam they take too long so they can show that it couldn’t have been done with another device. But that same scene could be told with the same effectiveness, and maybe even more, in less time.

Does the Steadicam really speed things up?

No, it slows things down. If you follow a moving object, you go more slowly. If you stay still, or it moves in front of you or it goes away or comes closer, the internal dynamics of the scene are more effective. In other words, everything has to be used with awareness and professionalism, because you need to know that if, while you’re using that device, you increase or diminish the speed of the story, you are increasing or diminishing the speed of the shot’s contents. That’s what you need to know how to evaluate and then use the Steadicam too if it’s needed, but only if it’s needed.

Regarding control of the supporting structure, can the Steadicam be stopped at the desired point?

With great difficulty. One shot that we did in Wolf8 with Garrett took a whole night and then it was cut because it never did come out well. I had already suggested we cut it, because I had designed it with a crane, an arm with the Steadicam on it, which accompanied the characters up to a certain point and then there was a cut, an out of shot. It was a terribly long shot to do and then it was cut after all. Then and there people thought that I didn’t want to do it or that I was having trouble with the lighting for it, but the lighting was always the same.

It involved going from the starting point, which was at the top of some stairs, towards a house where there was a party, where the two characters meet, they go down the stairs and towards a certain place. Doing it in pieces, in other words, one part going down using the crane, then cutting away from the scene and then instead of starting from the same place, starting 150 m further along with the house already behind them, would have made it more effective as a story.

Following that movement realistically you have a meaningless view in the background for 150 m. We did it with the Steadicam and they cut that piece, they had to enlarge the scene optically to be able to change it.

You know that to cut directly onto the same scene – they made it worse than what I had suggested.

Are there movies (for example, remakes) that are able to tell the story better because of the technical means that exist today (Steadicam, Skycam, etc.)?

No, I never had a problem with equipment being mechanically inadequate, but then I’ve made a lot of movies and sometimes the lack of something makes you think better, and more, and find solutions without leaving them to someone else. ‘Here, this could go there, I can do it anyway with that’. You have to think what exactly would be most effective and then do it. I never suffered from not having the Steadicam, not even now that it’s available, that it’s used. I have pictures of Blasetti many years ago with a sort of Steadicam he’d designed – a little helmet with a camera mounted on it, it was the same thing, more or less. Let me say once more, however, that the hand-held camera has always been in use here in Italy and not only here, also abroad, I think.

Can the Steadicam be considered a refinement of a technique that already existed?

Yes, just like film has gotten better, but it’s still film. It’s more sensitive, it needs less light.

What about the fact that the Steadicam moves sideways, that it can move more smoothly?

It’s more limiting than a hand-held camera, if you consider the effect. The smoothness of the movement is another question, but this isn’t always useful. The braking is dangerous, in my opinion.

What do you think about Steadicam shots with regard to framing?

By preceding someone who’s walking, you don’t make things go faster (apart from the fact that you can do it with any device: a dolly, a dolly with a jib arm, a camera car, a car, by hand). If you want to accelerate the movement behind you, you have to take it from a three-quarter view, because then the speed of what you have behind you is greater.

Even dollies, if they’re not used carefully, won’t increase the speed or rapidity of the movements or, say, the feeling of movement; they can absorb it, deaden it. Following a person means, I repeat, absorbing his movement, because you do the same movements and 30–40 per cent of it is lost, absorbed by your following him. So you have to really understand it.

Also, you see, the positions for preceding someone are always a little bit awkward and then they lengthen the time, as I said, and this is contrary to our modern style because the modern style is to tell a movie more rapidly, in the sense of skipping lots of parts of the story that were once thought necessary. The public today catches on sooner. In other words, if from this hallway you have to go outside and you want to follow someone on the stairs, all you have to see is someone who’s running away, you catch him again down below and you’ve cut out a whole piece giving exactly the same idea, without losing anything of the story but with a speed which is three or four times greater; the editing is faster. In other words, time, the seconds that you take to tell it are more rapid when you cut away than when you follow, because that’s real time, the other is cinematographic time.

With regard to screenplay, should it be decided from the beginning if Steadicam is to be used?

Not nowadays, if someone does it it’s very rare. You write a screenplay because you think first of all of the story, then if someone wants to do a story for the Steadicam, that’s different. But normally someone writes a screenplay, tells about human events, about human moods, and then later studies the means.

Are all camera moves studied later?

Certainly, all of them later. First you have to find where you’ll be shooting; after having done the screenplay you look for the locations, to decide where to shoot – there has to be an office, a major street, big stores – in other words, what the story needs and after that, according to where they are, and, again, according to the time that you want to give to that move, that scene, you choose the technical means.

Have you ever used the Steadicam in other fields – TV, dance, etc.?

In TV they don’t know how, they move the camera as if they invented it, instead they make you sick at the stomach, it’s really annoying.

A story has to have a life of its own and then, afterwards, the technical means should make the passage from the screen to the viewer clearer, taking the words and translating them into images. Let the viewer get inside the story and be captured by it, in other words, become part of it.

Giuseppe Rotunno, Director of Photography

Giuseppe Rotunno first worked as a still photographer at Cinecittà, with Arturo Bragaglia and, later, as a camera assistant before becoming a camera operator on several movies, beginning with Rossellini’s L’uomo della Croce.

In 1953 he made his debut as Director of Photography on Visconti’s Senso. He has become an important cinematographer at the international level. As well as for his early work in black-and-white, he is well known for the particularly warm quality of his colour photography.

During the 1970s he often worked with Fellini and, in the 1980s and early 1990s, he worked on many Hollywood productions. He was nominated for an Academy Award for the cinematography of All That Jazz (1979). He has been awarded many prizes for his work.

He has been a Professor of Cinematography at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia di Roma since 1988.

Films

His films include Le notti bianche, L. Visconti (1957); La grande guerra, M. Monicelli (1959); Rocco ei suoi fratelli, L. Visconti (1960); L’ultima spiaggia, S. Kramer (1959); Il gattopardo, L. Visconti (1969); Roma, F. Fellini (1969); Amarcord, F. Fellini (1973); Casanova, F. Fellini (1976); Prova d’orchestra, F. Fellini (1978); All That Jazz, B. Fosse (1979); Popeye, R. Altman (1979–1980); Five Days One Summer, F. Zinneman (1982); E la nave va, F. Fellini (1982–1983); American Dreamer, R. Rosenthal (1983); Rent a Cop,

J. London (1986–1987); The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, T. Gilliam (1987–1988); Mio caro Dottor Grasller, R. Faenza (1989); Regarding Henry, M. Nichols (1990); Wolf, M. Nichols (1994); Sabrina, S. Pollack (1995); La sindrome di Stendhal, D. Argento (1995); Io mi ricordo, si io mi ricordo, M. Mastroianni and A. M. Tatò (1996).

Interview with John Carpenter (by fax), December, 1998

I decided to interview John Carpenter under the mistaken impression that he had used the Steadicam in his film Halloween. In the late 1970s, in fact, the Panaglide, a Steadicam clone, responded to the same technical and narrative requirements as did the Steadicam.

I analysed the movie and studied a number of sequences in point of view that demonstrated a Steadicam effect, without knowing that they were actually done with the Panaglide. I think it is important, nonetheless, to include the observations I made upon seeing the movie, since the narrative intention in using the Panaglide is equivalent to that of the Steadicam.

In the interview which follows the discussion of Halloween, Carpenter discusses the technical and other reasons which led him to use the Panaglide in response to questions I had formulated about using the Steadicam.

Halloween (John Carpenter, 1978)

The film tells the story of a babysitter who confronts, on the night of Halloween, an escaped maniac from a mental hospital who, when a child, had killed his sister.

I must emphasize that the comments made about Halloween concern exclusively the film’s ‘Steadicam effect’ and the use of the Steadicam/Panaglide to recreate subjective vision. This film was one of the first to use this device to represent subjective vision and to show us, without the annoying shaking that would make the camera too evident, what the killer sees as he murders his first victim.

The Panaglide is used from the first sequence to show what the killer sees as he draws close, following every step from the outside (garden) to the inside of the house in a continuous movement. In this way it is used both as the perfect embodiment of the character’s vision and as a recording of his movement (through the garden, entering the house, going through the kitchen, up the stairs to the room).

The effect of suspense is accentuated by the sound of his breathing, full of potentially aggressive connotations, as he puts on a mask, takes a knife in the kitchen and moves through the house in search of his victim.

The narrative gaze does not give us an objective distance from things, rather, it involves us in the killer’s movements and leads us in a single, long shot to the murder, which is revealed as having been done by a child.

During the film the narrator does not want to give us information about the identity of the killer or, at least, we are not shown his face and thus cannot recognize him. We have thus an ‘explicitly denied portrayal’ that always shows us only part of him, never his face, or else shows him through what he is seeing as he spies on and follows the other characters. An example of this is the shot in which a boy, leaving school, runs towards us, the camera moves slightly to the left and the boy bumps into someone, looks at him, is scared, the unknown person holds him away from him and then lets him go. We see the head of the man who, after the boy has run away, stays there for a minute, then turns and goes to the left, slightly anticipated by the Panaglide, and finally walks along the school fence following another child, with the camera always at his side but never showing us his face.

We have seen that the story begins with a point of view of one of the main characters, the murderer; everything is seen through his eyes and in first person. For the first five minutes he is at the controls, then, after the murder, a more neutral narration takes over, the vision becomes total and no longer seems to belong to one specific character.

The tension in the movie is created by the question of which character is seeing what is on screen and the narrative voice continues to play this game, simulating and hindering the vision, limiting the audience’s knowledge. Thus the narrator, who coincides with the camera, seeks to maintain its role as giver of information and allows itself to linger on and ‘reframe’ certain situations in order not to give us a total picture of the murderer.

What is your opinion of the usefulness of the Steadicam in filmmaking?

The Steadicam has become a basic photographic tool in the movie industry; beyond useful, the Steadicam has become seminal.

When did you see the Steadicam used for the first time and what about it impressed you?

I became fascinated by the Steadicam after I saw a shot in The Exorcist II, of all things. It was a bird’s point of view, I believe, swooping down a street somewhere. It was not a hand-held effect – rather, a gliding, sweeping shot. Extremely cool.

When and why did you decide to use it in one of your films?

I first used the Steadicam in a television movie, Someone’s Watching Me, in 1978. I photographed Lauren Hutton dashing around her apartment, and her moving point of view of same. It was great. Immediately after this, I made Halloween.

I used Panaglide in Halloween, and have in almost every movie since. Panaglide is a Panavision-built Steadicam designed for use with Panavision anamorphic (widescreen) lenses. The Panavision anamorphic lenses are heavier than spherical lenses (standard 1.85 format), therefore requiring an operator with a great deal of lower-back strength. I strapped on the Panaglide and began walking around with it back in 1978 – for about 15 seconds. I screamed, ‘get this damn thing off me!’. It was a very disappointing day – I had dreams of operating the Panaglide myself. No lower-back strength.

Is your filmmaking technique – past and present – influenced by the particular features the Steadicam offers?

The effect of the Panaglide on screen is fascinating. Footage photographed with a Panaglide falls somewhere between the effect of a conventional dolly-operated shot and a documentary-style hand-held shot. The gyroscope in a Panaglide smoothes out the jerks and jitters of hand-held footage [author’s note: this is a common misconception; there is no gyroscope in either the Steadicam or the Panaglide], thus it resembles a dolly-shot. But there is a slight sailing or drifting effect. The Panaglide makes the image float [author’s note: practised Steadicam operators consider this ‘floating’ effect the giveaway of an unskilled operator].

Panaglide/Steadicam liberated the dolly move. Now an operator can strap on the camera and follow actors up and down stairs, in and out of buildings, over hills and valleys.

Whenever I direct a movie, I try to know as much as possible about the photographic equipment I’m using. I need to know how long it will take to set up a certain shot and what effect I want that shot to express. One of the issues I’ve confronted in the past is the moving point of view shot, in which a character is walking or running or basically on the move physically. I want to photograph, then, two different shots, to get the audience to identify with this character.

If you watch Alfred Hitchcock’s films, you’ll see he used a conventional dolly to photograph actor and moving point of view. I wanted to use the Panaglide instead. The freedom of movement, the gliding effect, the speed and mobility of shooting – it was all a plus.

Do you think the Steadicam has changed the manner of filmmaking?

See above.

To what extent is the Steadicam a tool of the narrator and to what extent can it be a narrator itself?

To discuss the aesthetics of Panaglide as a tool of the narrator or narration, I’d like to stop briefly at a boring history lesson.

There are really only two distinct styles of cinema. One is Russian montage. Think of Eisenstein, the Odessa Steps sequence in Battleship Potemkin. A montage is a series of shots cut together very quickly, creating excitement in the audience regardless of image content. A television commercial is exciting to watch because the images flash by so fast. A modern action film such as Armageddon is exciting because every scene is a rapid montage. It resembles a person watching a flickering light.

The second basic cinematic style is German Expressionism. It involves long shots, often single takes, usually with camera movement, exploring an environment, revealing characters or action. Think of Orson Welles, the opening tracking shot in Touch of Evil, plus the one that occurs later in the picture that takes place in the motel room. The emotional effects of German expression are excitement in the grandeur and sweep of a locale, a melancholy and sometimes anxious feeling regarding characters and locations. The Panaglide can be used to service both forms of cinematic style. It can become narrator or narration.

When making a film, what are the reasons for which you choose the Steadicam for a particular scene (from a technical and narrative point of view)?

See above.

What do you think of the point of view shot? Can you tell me something about using it in Halloween, i.e. the choice to have the Steadicam take the character’s point of view? Do you think the Steadicam was essential in realizing your narrative intention?

I love point of view shots and sequences. I made the Panaglide double for both characters’ point of view and narration point of view. It was absolutely essential for narrative intention.

What do think about hand-held shots and how they indicate the use of a cinematic tool as well as making the filmmaker’s presence felt?

Hand-held shots give the sense of chaotic movement. The audience doesn’t really intellectualize it the way you have, sensing the presence of the operator. They accept hand-held as moving chaos.

What do you think of the possibilities the Steadicam offers in terms of continuous or real-time shooting (in the sense of the possibility of following an action without interruptions of space and time)?

See above.

Do you think there is an abuse of the use of the Steadicam?

See above.

Do you always work with the same Steadicam operator(s)?

No.

Speaking as an author and narrator, how do you use the camera – as narrating eye, as third-person narrator, etc.? Is your choice influenced by the means you are using for filming? How?

My choice of using the camera as narrating eye or third-person narrator is influenced by the story, characters and intention of the scene I’m shooting.

Is the Steadicam such a strong means that it ends up imposing a certain style or can it be controlled by the filmmaker?

Any movie technology can be controlled by a director, given that he or she understands its strengths and weaknesses.

Does the fact that the Steadicam is such a versatile instrument affect the way you control the framing and shooting of an image? How much of what occurs in Steadicam shots is planned and how much is determined during shooting by the operator?

I dictate the direction of the Panaglide. During a shot, the operator watches the framing on a small television monitor attached to the rig itself. I’m right behind him, following along, watching both the shot and the actors in front of the camera.

Do you think the Steadicam will be responsible for creating a film genre (or has it done so already)?

No.

John Carpenter, Director and Composer

John Carpenter began making short films in 1962, winning an academy award for Best Short Subject (Live Action) in 1970 for The Resurrection of Bronco Billy. He has worked in the film industry in numerous capacities – as a writer, actor, composer, editor, producer and director. He co-wrote the screenplays and composed the intense musical scores for all his movies. He is particularly interested in horror and thriller genres, blended with the fantastic. He is sometimes credited as Frank Armitage, Rip Haight, Martin Quatermass or John T. Chance.

Films

As a director his films include: Dark Star (1973); Assault on Precinct 13 (1976); Someone Watching Me! (TV)(1978); Halloween (1978); Elvis (TV) (1979); The Fog (1980); Escape from New York (1981); The Thing (1982); Christine (1983); Starman (1984); Big Trouble in Little China (1986); Prince of Darkness (1987); They Live (1988); Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992); Body Bags (TV) (segments The Gas Station, Hair) (1993); Village of the Damned (1995); In the Mouth of Madness (1995); Escape from L.A. (1996); Vampires (1998).

Interview with Mario Orfini, Rome, July 1998

When did you first use the Steadicam?

I’m not sure, I think it was in Mamba.

Does the Steadicam condition your choice of how to shoot a scene?

Yes, the Steadicam can condition your choice of how to shoot a scene and that’s why the Steadicam has a lot of mistakes on its conscience – because people treat it as if it were the director, in every sense of the word. It’s not the director, because anyway it’s just a tool, and the person using it has to know how to direct it.

Eighty per cent of the time, in what I’ve seen of the Steadicam in Italy – in America much less – it’s used wrongly, taking advantage of and abusing its worth; in other words, it’s used automatically, without understanding its real value and real effectiveness. The Steadicam, like other cinematographic tools, can modify language and, if it’s used haphazardly, it leads to enormous mistakes.

The most important thing is choosing when to use it, on the basis of what you want to express and narrate. Lots of times I’ve found myself deciding whether to use the Steadicam, the hand-held camera or the dolly, and I’ve had to think about what was important to narrate, about what I wanted to tell. And when I’d thought about it I’d say, I’ve chosen the hand-held camera or the dolly or the Steadicam, whichever, but I was always very sure of my choice. I could see in my head what I wanted to do and which was the right tool to use to get the result I wanted. So for me personally it’s never been a problem.

Is there a difference between predicting the effect of a dolly shot and the effect of a Steadicam shot?

No, I don’t think so, because a dolly might seem to be something simple that you know very well because it’s in your genetic code – it was around a hundred years before the Steadicam so it’s lodged deep within the layers of the director’s memory, the person who knows how to narrate with images and how to translate words into images. The dolly is part of our inherited knowledge, our heritage. The Steadicam comes along as the last tool, so then you have to decide if you’ll use the dolly or the Steadicam.

And when do you decide to use the Steadicam?

When it’s impossible to use the dolly or the hand-held camera I can depend on the Steadicam, but in this way I’m running the risk of undervaluing it. The Steadicam, besides having a language of its own, has something more, though it can substitute for an aspect of a dolly or a hand-held camera.

When you shot Mamba was the Steadicam very important?

No, when I was thinking about Mamba I never took into consideration what tools I would use. At the beginning, right before we started to make it, I said I wanted the Steadicam as well, because it could be useful, but I hadn’t planned at all where, or how, or when. I thought up all the Steadicams in that movie one morning from 7:00 to 8:00, while I was being driven to Cinecitta. The fact that I had to have a Steadicam available caused a lot of trouble for everyone, but since I was the producer I could decide, and so one was made available.

Were there difficulties with using the Steadicam in that movie?

No, not at all. However, I can tell you that in the last movie I made, L’Anniversario, I did have problems with using the Steadicam, not because of the instrument but because of the operator. He was very, very good at his job, but one day when I had to do a difficult Steadicam shot – he had to start in front of the actor and then go around to follow him, with a double circle around a table at which the actor was sitting, then go out the door, with the door acting as a curtain, go away, climb on a dolly that raised him up, and shoot the actor as he appeared in the doorway in a Full Shot (FS) to give the idea of the total breakdown of this character who psychologically had lost his entire vision of life. I needed to show him isolated in this doorway, seen from above. The operator had a 40° fever and he couldn’t control the Steadicam – not its weight, which would be a banal consideration of the job that a Steadicam operator does, but he couldn’t get the right tension. The operator and the Steadicam are two parts of a whole, and they breathe together. Seeing him in difficulty, I had a feeling of the Steadicam being in difficulty as well, and I did something that I don’t think anyone else would have done. I used the Steadicam sequence in which he had had the most trouble. This situation enabled me to obtain a strange mechanism of liaison: when there was one mistake, it seemed like a mistake; when there were two, three, four, imperceptible mistakes it seemed like the Steadicam was breathing, as if it took a breath and wanted to get closer to the character it was showing us. In the end we got a really beautiful sequence.

Does the fact that the Steadicam makes it possible to shoot a series of free movements mean that you tend to simplify the story?

I don’t think it conditions the way you shoot the story. For me personally, no. First I think of how I want to compose the shot. It would be a big mistake if I were to follow the tool and not what I want to tell. You could say that it’s more true for television than for movies (except for ‘B’ movies).

What do you think of point of view shots?

A point of view is almost always shot with a hand-held camera, sometimes with a dolly, and sometimes it is better to use the Steadicam for it. It depends on what you want to say and how you want to say it. The Steadicam is absolutely a tool that you have to know how to use, because if it’s used badly it’s wrong, like with all tools.

Does the Steadicam impose a certain style?

It can’t impose a style, because if it imposes a style it means that the director wasn’t able to control it.

Can it lead to the creation of a new genre?

I don’t know about that. It can at times be conditioning, and thus I’m contradicting what I said earlier a little bit, when a sequence or a scene is being made. I can say that in the last movie I made I used the Steadicam four or five times and I massacred two of them when I was doing the editing, because I realized that in order to have the softness and flow of the Steadicam I was losing the rhythm. Because with the Steadicam, you also get the intervals when nothing is happening. You can do that in television, but not with movies. For example, there’s a scene in which Laura Morante, the main character, goes out, I’m in front of her and I follow her as she closes a series of doors behind her, and I kept jumping from one to the other. You could do an entire movie in Steadicam but it would be an exception. But in my situation I realized in doing the entire sequence with the Steadicam that in the end when we edited it I had to cut a lot to have the rhythm I wanted. That doesn’t take away from the fact that the Steadicam parts that we kept in the movie are beautiful, just right.

From an author’s point of view, how do the means of shooting influence your choices?

The means must influence your choices, because if you’re deciding how you’re going to tell something you ask yourself what tool you’ll use, and then you choose it on the basis of the various characteristics and on what you’re telling.

How do you use the camera – as a narrative eye, as a third-person narrator?

Both things, and not only those, also in a lot of other ways, because there are situations in which you see in first person and then a second later you feel the need to step aside and look at the situation objectively. For example in my last movie, I had a situation of guests in a house after a dinner party, and the hosts and their friends use a language in which the uselessness of words and gestures is exalted. What they say has no real content. There are two women in this group who have something dramatic in them, and that needs to be seen in a different way. In this case, I thought that to be able to distinguish between these two ways of narrating, I had to do something with the camera, and I shot from up high, flattening the actors, seeing the heads and the noses of the people talking, and other times they were placed a little differently and you could see a little of their faces. But I made it feel like a vertical shot that nullified them, flattening them to the ground.

How do you control the shot with such a versatile tool?

I think that you can calculate everything, and what the operator makes happen is that little extra touch that comes from the camera being sort of a part of the operator’s body. That’s the sensitivity the operator has. It’s like ballet, if you see Carla Fracci or Maya Plissetskaya you realize, you can feel, how they’re able to become light, and you can feel when a ballerina is too heavy, too hard, etc. This is what the Steadicam operator gives you, and a good camera operator gives it to you as well, that you don’t feel the camera and he and it are one. He feels the image and he makes it his own, moment after moment, capturing it in the lens.

Can using the Steadicam change the narrative message?

No.

Do you think the Steadicam is abused?

Yes, enormously, by everyone who uses it in the wrong way.

What is your relationship with the viewer, with regard to his getting narrative information?

I think that in the end the viewer understands everything, so I put myself in a position to be able to give him what I see, which is very important. I mean to say, I don’t become a narrator who is present, a narrator who’s also the object of the narrative. In this movie, L’Anniversario, I used two cameras a lot, but not one next to the other, like in ‘Put a 200 here, and a 100 underneath’. No. ‘Put a 200 here and a 40 down there at the far end’. They couldn’t figure out where to put the lights and the mikes anymore, but I didn’t care and I was right, because like that I always had an ‘eye-witness’ to the events. In other words, I observed a situation and then to make it more important, to reaffirm the narrative importance of that situation, I asked a witness to watch and to say ‘It’s okay like this’, and the witness was off to one side and it was another camera. For the viewer it was as if the second camera was him looking at the scene from a different viewpoint.

What do you think of shots with the hand-held camera?

The hand-held camera is a tool like the Steadicam, or the dolly. As with all tools, you have to overcome your prejudices or get something straight: behind the gaze of the hand-held camera, behind the gaze of the Steadicam, behind the gaze of any lens, there is always a viewer, the one who’s watching. The director is a mediator, someone who’s telling a story. He uses these tools to tell the story. If he’s good at his job, he tells it to you well, and if he’s not, he tells it to you badly.

The viewer is the one who sees it and he’s the one who feels himself embodied by the lens at that moment, so if I use the hand-held camera and the hand-held camera is more present, it’s because in that moment the director has chosen to narrate with the hand-held camera. The birth of the Steadicam didn’t eliminate the hand-held camera.

In my last movie I used both the hand-held camera and the Steadicam a lot, according to the situation. There were things which were unthinkable for the Steadicam; for example, the husband saying to his wife ‘Now I’m going to throw you out of the house’ and he takes her and drags her down the stairs to finish packing her stupid suitcase so that she’ll leave. At that point, I didn’t have any doubts at all about whether to use the Steadicam or the hand-held camera, I used the hand-held camera because the tension of the break-up of their relationship was that of the hand-held camera. If I’d used the Steadicam I would have annulled the roughness of the scene. The action was more physical and if I had softened it, because with the Steadicam I would have softened it, I would have ruined that scene. So they’re two different things.

What do you think about continuous shots?

I think very highly of them when they’re not abused and when they’re not used wrongly. When they’re done with the Steadicam, which does the job much better because it can do the ‘impossible tracking shot’ or the ‘impossible dolly’ and lets you do things that would be impossible by any other means, almost always the main mistake is wanting to keep the entire shot, to say ‘Look what a great 7-minute shot I did!’. Orson Welles would be rolling over in his grave. Instead, you have to use the Steadicam to do tracking shots, dolly shots that would be impossible, but then you have to cut them in editing to eliminate the things that pollute the shot, including the times when nothing is happening.

In the example I gave earlier, the Steadicam helped me create an almost magical sequence. Then, evidently, the Steadicam did its work well, it became a violin that was playing beautifully, despite the fever. You could feel that the bad shape the operator was in matched perfectly the bad shape the character was in, which was what the Steadicam was telling you about, and the whole thing increased the total effect. Although it’s true that if a Steadicam shot has a mistake it should be done over, in this case it was the contrary: the tool – the Steadicam, which was breathing with the operator – took on the same feverish and weak conditions the operator was in, recording the feeling, and shooting the character’s drama with his same feelings.

Mario Orfini, Producer and Director

Mario Orfini worked for years as a reporter for a variety of European and international publications, writing for Pannunzio’s Monao and Espresso. He also worked as a photographer for the Piccolo Teatro of Giorgio Strehler.

He is a producer with a curriculum rich in discoveries and sophisticated quality films by authors such as E. Greco, R. Faenza, F. Carpi and others. From 1991 to 1992 he was responsible for production at Titanus Distribuzione.

Recently he has been financial co-producer for the film New Rose Hotel, directed by A. Ferrara.

He is the president of Millennium Productions.

Films

He directed Explosion (1971); Noccioline a colazione (1978); Mamba (1988); Jackpot (1992); L’anniversario (1999).

Interview with Larry McConkey, Perugia, October, 1998

I would like to know what you think about the point of view shot.

It’s the most difficult thing I have to do, but it can be the most rewarding. One nice thing about the Steadicam is that it can mimic the motion of human eyesight better than any other currently available technique. As you walk, your head is naturally bobbing up and down with every step, along with some side to side motion, and accelerations to the front and back that are less significant visually, but next time you think of it, notice while walking that you tend to focus on something in the distance and keep that steady, while the rest of the world, normally the foreground, moves up and down relative to it, and of course, a little side to side as well. This is a remarkable form of image stabilization that is just natural to us, and the Steadicam, because it is inertially stable, tends to do the same thing. In fact, a good operator will not only make the background steady but the foreground as well. This is a kind of hyper-natural form of image stabilization. So first of all that’s why the Steadicam is so nice for trying to represent point of view shots – because it’s seems pretty natural.

Figure 4.2 Larry McConkey at the International Steadicam Workshop, Perugia, Italy, 1998. Photo: Serena Ferrara

The more difficult part of representing an actual point of view is deciding what to show in the very narrow field of view that almost all lenses provide, particularly the normal-focal-length lenses that present a perspective that closely matches our own eyesight. As you walk, you tend to glance quickly around at a number of things all around and your mind constructs an apparently seamless presentation of the visual reality. In fact, most of your visual sense is nothing but an imaginative reconstruction from memory that your mind fits to the available clues that your eyes and other senses provide. So, to represent this complicated process with a Steadicam point of view, I use a technique of presenting one clearly defined visual idea after another, allowing the audience to construct their own sense of the overall visual reality from this series of ideas. I go through the space defined by a shot and imagine being the character, what he or she is concerned about, what he or she is feeling. I am in essence playing the role myself, using camera technique rather than acting technique, so I try very hard to get the actor to play the scene first, and ask questions about what I should be thinking, feeling and doing. The trick is to turn those ideas into specific shot making techniques.

Yes, but don’t you think that when you watch a movie, often the very smoothness of a Steadicam shot brings your attention to that fact that it was shot with a Steadicam?

Well, there are two answers:

First, before Steadicam, it used to be the convention that if you want to tell the audience ‘You are watching a subjective shot’, you do it hand-held, and the inertial unsteadiness, the shaking of the shot is what alerted the audience that this was supposed to be a point of view. I think it’s an overused and less convincing technique, but it is easy and it lends itself nicely to suggesting a spontaneous reaction to the scene, which is possible, but more difficult with a Steadicam. These days the audience is being trained to recognize another convention for point of view when they see a very smooth, very wide-angle shot that moves somewhat aimlessly through a set. I don’t like either convention very much.

Secondly, bad technique and execution will call attention to the process rather than the action, no matter how it is done. But if what you do is present the audience with a series of ideas, clearly executed, they don’t notice the crane, dolly, tripod, Steadicam or hand-held nature of the shot, they just see the ideas, and then it’s a good shot. I feel the Steadicam, handled well, is one of the most expressive and powerful tools you can use for this, but it is a two-sided sword and, handled badly, it can be one of the most offensive, crude and obvious tools we can use. That is always the challenge for me … walking that tightrope between sublime and subversive. I am always at the edge of completely subverting my intentions through the smallest failure of technique, physical condition, mental preparation and concentration, emotion or sometimes most significantly, political skills. That challenge is a large part of the attraction of the job for me.

I think it’s much harder to do a subjective shot well than anything else. Because what I want to do within a point of view is to express a series of purposeful, simple ideas; for instance, as part of a shot, I may want to portray a character who’s absolutely determined and absolutely clear about what he wants to do, and nothing is going to stop him – he wants to go through that door ahead of him, and confront something on the other side. He doesn’t care about anything else in the world, he just wants to go through that door and there may be no extraneous movements in the frame – nothing to grab the audience’s eye other than the set. To do this I need to place that door very deliberately and precisely in some part of the frame and it becomes my target: ideally, it never wavers from that part of the frame, it just gets bigger. Any little bumps distract from the idea of going to the door and they are very noticeable because anything but a steadily growing image of the door is new information, a new idea, and the audience will be startled by it, and they will notice the movement of the camera instead of the simple but powerful idea that the character is moving resolutely to the door. The more perfect your technique, the less you feel the Steadicam and the more you see the idea.

How do you organize and execute a long, unbroken shot?

One reason editing is nice is that it allows you do a section of the scene from a fixed position, or as a dolly or crane move, until it stops working for some reason. A new angle is established and the scene continues, perhaps with some unnecessary action cut out as well. If I am asked to do an unbroken Steadicam shot in the same situation, I have to figure out another solution. I may want to get to that same second angle, but without making the audience feel like they are just waiting for me to get there, or feeling that the camera is rushing to a new position for no apparent reason. As a general rule, I want the camera movements to seem expected, desired, even inevitable by the audience. I don’t want arbitrary movements, unnecessary movements of either the actors or myself that don’t contribute directly to the story. Often that means that I must manipulate the physical space. I might move parts of the set or people to create a different space where the actors can move logically and allow me to respond with the camera without calling attention to myself, as I would by moving in a direction or speed that might seem undesirable to the audience, and also to end up where I want to go.

This often introduces some new ideas into the scene, but to be helpful they have to be consistent with the story, they can’t seem arbitrary. So I must respect the needs of the actor, and the ideas of the director, and get help from anybody who can supply it. For instance, in Goodfellas9 I needed to tamper with the shot, I needed something for Ray Liotta, the main character to do, because otherwise he would just be walking through the club and the audience would just be waiting to get inside. I thought if we asked him to deal with other people along the way at strategic places where I needed help to keep the shot going – maybe he tips them or maybe he just talks to them – suddenly those events become the story, how he talks to these people, what he says to them. These technical challenges lead to solutions that enhance the drama. It’s magic when it works like that, but that’s what makes the difference between a long shot and a great shot.

Is it always necessary to shoot with the Steadicam or is it maybe possible to use other means?

I think that the best way to do anything is the simplest way, I mean the simplest looking way, not necessarily the simplest to execute. The simplest, whatever it is.

The Steadicam is capable of very complex things and sometimes there is nothing that can handle a complex shot as well. But if you are a good operator, it’s also capable of beautifully simple things. There is nothing more pure than the camera simply panning at a perfectly constant rate in a wide space or tracking sideways with perfect direction and smoothness – just those simple ideas, just pure movement through space. Now the Steadicam can do these things, but there are other instruments that also do them and often do them easier or better. But I don’t like to impose limits on myself without first attempting what initially seems too difficult, or at least unnecessarily difficult with a Steadicam, and I have done many shots that at first I didn’t think were appropriate for Steadicam. Sometimes you can get exactly the same shot two different ways – which is the more appropriate often depends upon the priorities of the moment. Sometimes it’s better to use a Steadicam because it’s faster, sometimes it’s better to use a Steadicam because the operator can make a more beautiful response to a little sudden change in the scene, sometimes it’s better to use a dolly because the Steadicam operator is tired.

When asked to do a shot that I knew would be fairly simple shot with a dolly, I have at times responded by asking ‘Why don’t you use a dolly?’ I might not get much more explanation than ‘I want you to do it’ or ‘Let’s just see how it goes …’. After operating Steadicam for about twenty years now, I’ve learned it can be worthwhile trying to stretch my abilities in attempting these shots. Earlier in my career I would have thought some things should only be attempted with a dolly – simple, beautiful moves without deviation, just perfect tracking, booming or panning moves. But I have learned that if everything is going well I can make those same moves – if I’m in very, very good form and if there’s no wind, and if I’m rested, and if the equipment is in perfect shape. I can make those moves, plus I can make adjustments during those moves just as a good operator and dolly grip might, but I can make the adjustments with one mind, whereas the dolly operator and grip are often making very subtle corrections for each other and what you see is a series of very small corrections. I can do the same thing but without the corrections, so those same little adjustments look more organic and human and they can sometimes even convey emotion. It is in the little subtleties that I find the most satisfaction and I might look for the opportunities to respond emotionally, almost intuitively to an actor. One example might be: I watch the actor’s eyes and some small change in them makes me want to look more closely to see what he is thinking. In my mind I think ‘what’s happening?’ and the response I make with the camera is almost nothing. And on the screen you see a little schh… sound that Larry made to synthesize the action of panning. It is a small but sudden movement, and it’s a deliberate but almost instinctive reaction by me. I’m responding as if we were linked together, like a breath, so my camera becomes like another person and the audience becomes connected through that person to the other actors. The audience becomes more empathetic, more involved. The actor cannot help but respond to my camera as well, and we become even more closely linked together, and hopefully, the audience feels like it is participating in the scene.

Larry McConkey, Steadicam operator and Director of Photography

Larry McConkey works as a Steadicam operator – specializing in ‘long takes’, e.g. Goodfellas, The Bonfire of the Vanities, Raising Cain, Snake Eyes, Carlito’s Way and others – and also as Director of Photography for documentaries, music videos, commercials and one forthcoming film, White of the Eyes.

He teaches as a Steadicam Master in workshops all over the world.

Films

His films include: Birdy, A. Parker (1984); After Hours, M. Scorsese (1985); Legal Eagles, I. Reitman (1986); Mosquito Coast, P. Weir (1986); The Untouchables, B. De Palma (1987); Witches of Eastwick, G. Miller (1987); Casualties of War, B. DePalma (1989), GoodFellas, M. Scorsese (1990), The Bonfire of the Vanities, B. De Palma (1990); Miller’s Crossing, J. Coen (1990); The Silence of The Lambs, J. Demme (1991); At Play in the Fields of the Lord, H. Babenco (1991); Raising Cain, B. De Palma (1992); Carlito’s Way, B. De Palma (1993); The Age of Innocence, M. Scorsese (1993); Mission Impossible, B. De Palma (1996); Ransom, Ron Howard (1996); Snake Eyes, B. De Palma (1998); Celebrity, W. Allen (1998); Summer of Sam, S. Lee (1999); Bringing Out the Dead, M. Scorsese (1999); Three Kings, D. O’Russel (1999); Mission to Mars, B. De Palma (2000); and many others.

Interview with Nicola Pecorini, Volterra, November 1998

What do you think about the Steadicam?

My opinion of the Steadicam has a lot to do with how I discovered it with respect to what I was doing before, which is that I had worked in 16 mm for Switzerland’s Italian television for almost three years. I was part of a ‘film team’, which means that I had a 16 mm camera, then there was a sound man, a journalist and/or a director. We’d go around doing a little bit of everything, a soccer game or a documentary on spiders or an interview about elections in Germany, so I was used to always being frustrated with regard to camera movements, in the sense that I never got what I wanted, unless I could have done them by hand, on roller-skates. It was all a thing of trying hard but not getting very good results.

Then, while I was on vacation in America in 1981 I discovered the Steadicam. I did a course with Garrett and it was a revelation for me, because for the first time even by myself I could move the camera, I mean I could do ‘camera movements’.

The Steadicam is an incredible device that lets you move the camera where and how you want, and it has another enormous advantage, which is that the same person moves the camera and does the shot. I didn’t realize that right away, partly because what you need for doing documentary television is so different than what I later discovered you need when you’re making movies.

Figure 4.3 Nicola Pecorini and Vittorio Storaro on the set of Ladyhawke, Cinecittà, Italy, 1983. The operator is working with a Steadicam Model II, modified. Photo courtesy Nicola Pecorini collection

But above all, working more and more on movies, and more and more at a high level, I realized that one of the incredible advantages that the Steadicam offered was the fact of deciding when to start the movement, when to finish it, where to finish it, where to begin it, to adjust things if the shot’s not working, to adjust to the unexpected that can happen in normal life. In my opinion, this is the most incredible thing about the Steadicam. Actually, if you look at the last 50 years, it may be the greatest innovation ever introduced in how movies are made, especially in how movies on location are made.

In 1922 there were dollies which were absolutely comparable with the dollies we have today, in other words, the ‘technicality’ of making movies was already extremely advanced. It was halted when the sound cameras came out, because instead of moving a thing 60-cm long, you now had to move something that weighed 2 tons and measured 2.5 m by 3.15 m, which was impossible, so technically there was a return to 40 years before. Cinema was blocked, and the Steadicam made great mobility possible again, especially if you think that the Steadicam came out in 1976, so all those things that are available today, minidolly, minigib, all those things didn’t exist. You either got on a normal dolly, on a crane, or basically you didn’t move the camera.

I should also say that the introduction of the Steadicam was a good thing not only with regard to the possibilities for using it – in other words, the kind of shot that it lets you do – but also technologically. For example, all these things like radiofocus or remote focus, remote control, video transmission, all this technology that was developed above all to be used with the Steadicam, is now being used in lots of other ways. Now, for example, it happens really often that the assistant doesn’t get up on the dolly arm anymore to do the remote focus, which also makes things a lot simpler and quicker, and the grips don’t have to work so hard. In other words, life is simpler and more complete. If there weren’t the Steadicam, everyone would still be there with those wires, and all that stuff.

So for me that’s what the Steadicam is, and for me the Steadicam adventure, which is over now, was a great thing, because due to various circumstances I was there at the beginning, so you feel this thing of being a ‘pioneer’, which is really great.

Then, well, personally I’ve gotten a little tired of it, partly because I always had a sort of disenchanted view of the Steadicam. I mean, it was a tool like any other. Gradually, as I found other tools for moving the camera I realized that it’s like how I was at the beginning, jumping around and bothering everyone I was working with saying ‘Let’s do it in Steadicam, let’s do it in Steadicam!’, and then you could do it with the normal dolly, there wasn’t a real reason for it. There’s this way of thinking that the Steadicam is everything, that you can’t do anything without the Steadicam, and in the end you tend to take everything to extremes and lose sight of what the film’s needs are as a film in general, and to consider your contribution to the movie more important than it is.

In fact, this thing happens a lot. For example, when I went to America, I had a different approach to the Steadicam, which was ‘We need to do this, okay, 10 minutes, ready’, which is very rare as I found out later, because the others tend to say ‘Oh, we have to construct it, it’ll take two days’, a rehearsal here, a rehearsal there, etc., etc. It gets too exaggerated for the customer because he says ‘Okay, if the Steadicam makes things more complicated instead of simplifying them, I might as well just use traditional tools’.

I remember that at the beginning of my Steadicam adventure (I’m talking about the early 1980s when there were really only a few of us using it and I was one of the few who could make a movie from A to Z), there was a certain – not envy, but my American colleagues would call me every once in a while and say ‘You know, I’d like to make a movie from A to Z, how do you do it?’. First of all, you don’t drive a hard bargain, because one of the reasons that they would drive a hard bargain is very simply because if you do that you can ask to be paid more, which means that if you ask for US$2000 a day to do the Steadicam work, obviously they won’t have you doing the whole movie because it’s not worth it. It becomes something which has to be planned months in advance and if something unexpected happens and they have to change the shooting script one day, which happens all the time when you’re making a movie, you’re not available and they have to call someone else, and in the end it’s frustrating because you can’t even say ‘I did that movie’ because it’s not true. You contributed slightly to the movie, but there are movies that – at the beginning they didn’t even put your name on, but when they started to put the name of the Steadicam operator, there would be seven names,10 and you’d say ‘Who did that? Who did that shot? Me, no, him, I don’t know!’.

I mean, it becomes a purely mercenary relationship that, in my opinion, is counterproductive for the artisan who’s doing it, for the mercenary who’s doing it. I don’t know how you want to define it, but I’ve always disagreed a lot with this kind of system, with the result that I made a lot less money than they did. But I have to say that I haven’t regretted it, because I think it’s let me do a lot more interesting things than they have, and it’s let me stay with a lot of movies from the beginning to the end, which I wouldn’t have been able to do otherwise. Larry, for example, made the choice of doing only, exclusively, Steadicam, he doesn’t even do B camera when he’s on the set, whereas I find that I like to begin a movie, work on it, and finish it, so in the end I’ve found myself doing everything, A camera and, when it was needed, the Steadicam.

Do you think there’s an abuse of the Steadicam, owing to its capacity for movement, and because it can make shooting times quicker?

Yes, often. It’s a little bit in movies like it is everywhere but, for example, when the zoom came out it was absolutely abused, when the Tecnocrane came out, it was abused. I mean, there was a bit of masturbatory use of the tool with the Steadicam too and obviously we Steadicam operators were partly responsible for that, because at the beginning you’re so enthusiastic, you think you can do incredible things and in the end you do things which don’t have that much sense. I think that in the end, as I said before, it’s still just a shot, by which I mean that it has to have a logic, a purpose, be useful to the story. If it has that, okay, it can be Steadicam, you can throw it off the balcony, you can do what you want, you can leave it fixed where it is. If it’s only an exercise in style then in my opinion it doesn’t have much sense. It’s true, Kubrick used it for an exercise in style in The Shining, it was exactly at the level of an exercise in style, but he’s Kubrick, and at any rate in the end he makes masterpieces, even if flawed. But yes, I’ve done a lot of stupid things, really lots of them, and just as many times I’ve refused to do them. There is an abuse of the tool that however at the beginning was pretty justified, because Garrett’s invention was so clever, for example, the fact that you can boom up and down and you can change the height. Now with the new model it stays where you put it, first you had to hold it; it has a 90° radius. That’s an incredible freedom that the Steadicam has compared with any other tool, because the speed with which you can do it is incredible.

Back at the beginning when all its possibilities were being discovered, obviously there was an awful lot of experimentation. Then, in my opinion, that went on a little too long, because in the end those are the possible variations, you can’t do God knows what. It took a few years; I’d say that the Steadicam experimentation went on until 1983–1984, after which they kept on doing more or less everything but they didn’t invent anything new. Until 1985 they were doing good experiments both with its use and its applications. For example, in 1987 you could rent Steadicams in Italy. Before that, it was a disaster if you broke a Steadicam, you had to beat your head against the wall. Still, I think that the period from 1981 to 1984 was the best period, and the most fun, because we were discovering a new world of our own, and we did a lot of silly things that I don’t regret.

Do you think the Steadicam is capable of influencing the style of a movie, compared with a normal camera?

No, I don’t think so, it’s like saying, do the C major chord cadences oblige you to do a certain thing? No, with the C major chords you can do whatever you want. I mean to say, for me the Steadicam is like a saxophone instead of a violin, in the end you can play the same thing. They have a different sound, but in the end the music can be the same.

But does the Steadicam force you to use it in a certain way?

No, there are clichéd ways of using the Steadicam, it’s true, but not for me. For me that’s impossible, because I can use the Steadicam in fifty different ways. I mean, now, as Director of Photography, I always want it on the truck and lots of times I use it just because it makes things easier. For example, I have to be free to move with the dolly but the pavement isn’t one of the best. I mount the Steadicam arm on the dolly and I can go without any problems. I can shoot everything I want, even if there’s a dislevel, I skip it, if there’s a wire I skip it, nothing’s a problem. That’s not a Steadicam use, do you see what I mean? But I also know that if I mount the Steadicam on the dolly, if it doesn’t go to the mark, or if the operator doesn’t push the dolly to the mark, hop! I’ve gone to the mark, hop! I’ve bent down a little bit more or a little bit less. It gives me that option, too. Still, I find that for example, since I don’t like to operate the camera if I’m doing the photography because they are two different jobs that pile up, and if I’m not the one doing it, or someone that I trust absolutely, I’d rather not do it. I find that the Steadicam, despite everything, still has that big handicap, which at times is an advantage, which is that you have to have a handle on it. It’s useless to ask for a guitar solo if you don’t have a guitar player.

And what about television use/abuse of the Steadicam?

Well, I have to say that I enjoyed doing things for television, since I happened to be there at the right time, and I got a lot of satisfaction from the viewpoint of curiosity about applications. In Italy I worked on a New Year’s show on Channel 5,11 in 1982, with Raimondo Vianello and Sandra Mondaini. Davide Rampello was the Director and there, too, we did some very interesting things in Steadicam, especially because they were new things, strange things. However, because they worked there, they became clichés, like ‘we can go around the singer with the microphone’. It’s okay if you do it once, but when you’ve done it four times, it’s already boring. The intelligence of the user, in my opinion, isn’t the cliché. I mean, someone who lives off clichés will find clichés in any thing he does; it’s not the Steadicam, it’s not the tool.