The challenges and the future for business sustainability

Abstract:

The post-2008 global financial crisis and consequent economic turmoil indicates that organisations will either succeed or fail partly depending on their reactions and responses. All too typically, business processes are made unnecessarily complicated and bureaucratic when the solution lies in being simpler and reducing transaction costs. This chapter examines organisational views and business sustainability in terms of: core values; key challenges; reasons for unsustainability; measures taken; risk management strategies; and future challenges.

Introduction

The post-2008 global financial crisis and consequent economic turmoil indicates that organisations will either succeed or fail partly depending on their reactions and responses. All too typically, business processes are made unnecessarily complicated and bureaucratic when the solution lies in being simpler and reducing transaction costs. Strategies are often skewed towards short-term business profits, ignoring the long-term effects, which may well be deleterious. For instance, as noted by the Head-Asia Pacific (Talent Management) of an international IT company operating in Singapore, downsizing has become a more fashionable cost-cutting initiative (SHRI 2009). Interestingly, despite the short-termism of the US and UK, this knee-jerk reaction has not always been the case in parts of the West with the post-2008 economic crisis (see Rowley 2010a).

Organisations may resort to headcount cuts (and also pay package reductions). Yet, this action may then reduce an organisation’s talent base. If not handled properly, which is often the case, the demoralised staff that are left behind (often with ‘survivor’s syndrome’ as it is called) will be the next to ‘jump ship’ when the economic environment improves. This has echoes in a quote from a business leader, that: ‘Business sustainability is about being able to continuously innovate, implement and drive the right strategy to grow and sustain one’s customer base (including internal customers-employees), retain and grow leadership pool and adapting to tough changes’ (SHRI 2009).

We often see uncontrollable effects and analyse them in retrospect, most often ignoring the causes, which are far more controllable if the intention is for them to be controlled. To cope with economic downturns, many organisations close down business units that they thought were not significant for their future growth. A set of questions then arise. Is this actually a necessary measure? Are there any bigger problems in the system? It may be argued that in the post-2008 crises, the ‘right’s rights’ are often shadowed by the ‘wrong’s might’ – that the effect of the economic crisis was shared by the people who were probably the least involved (Mukherjee Saha 2009: 8).

Paradoxically, times of crisis are probably a good time, in terms of when fundamentally strong companies emerge, survive and succeed. Successful companies have a clear sense of business direction, while their business strategies and practices adapt to a changing world. They encapsulate and portray their business sustainability strategies through their corporate value system. For example, the secret of staying ahead in the competition lies in a core culture of nurturing creativity. These ideas can be seen in the case of the Discovery Networks Asia-Pacific. We show this in the box below.

The rest of the chapter has the following structure. We have five sections that cover and detail organisational views on business sustainability in terms of the following. First, core values, followed by key challenges, reasons for unsustainability and measures taken, then organisational risk management strategies and future challenges. These are followed by a conclusion.

Core values and business sustainability

Corporate values can be defined as first-order operating philosophies or principles to be acted upon and that guide an organisation’s internal conduct and its relationship with the external world (Serrat 2010). Thus, corporate values articulate what guides an organisation’s behaviour and decision-making and they can boost innovation, productivity and credibility, thereby helping deliver sustainable competitive advantage. This set of perspectives follows earlier views elsewhere. For example, HRM, and especially employee resourcing of organisations, are sometimes treated in a manner that has been labelled a ‘downstream’ or ‘third order’ activity (by Purcell, see Rowley 2003), that is, an activity which follows in the wake of the business strategy and which HRM practitioners implement in a somewhat mechanical fashion. This area is also linked to ideas of HR as the only ‘real’ source of competitive advantage (see inter alia, Barney 1991). Underpinning such views are ideas such as that: ‘People are the only element with the inherent power to generate value. All other variables offer nothing but inherent potential. By their nature, they add nothing, and they cannot add anything until some human being leverages that potential by putting it into play’ (Fitz-enz 2000: xiii).

Corporate values portray corporate identities. Core values form the foundation of an organisation and determine their stability and sustainability. The significance of core values is aptly narrated by the Chair and Chief Executive Officer of Ameritech (the parent of Bell Telephone in Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Ohio and Wisconsin): ‘When a corporation enunciates a set of standards and does not abide by them . . . when we talk one way but act another — people are torn in two directions, become cynical, and cease to take the value system seriously. This undermines the drive to corporate identity and to excellence. It is important, therefore, to encourage behavior consonant with the corporation’s values — even before the realization of attitude changes, which may require more time’ (Stackhouse et al. 1995: 704). Thus, it is imperative for organisations to focus on values before even trying to see the bigger picture of business sustainability.

Researchers (Donker et al. 2008) developed a ‘corporate value index’ (CV-Index) model based on a set of parameters. This model was applied to Canadian companies listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange. It found statistically significant evidence that corporate values in general are positively correlated with firm performance and sustainability.

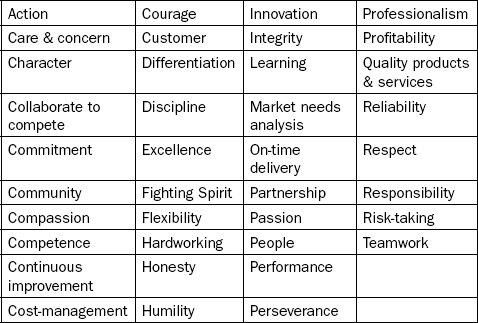

Corporate values are often inscribed by organisations in brochures, websites and other branding materials. These provide a snapshot of their characteristics and indicate their focus in doing business. The range of corporate values exhibited by the organisations in this book is quite varied – from loosely defined unstructured adjectives to focused and integrated objectives. It is interesting to note that most of the organisations in this book have corporate values revolving around a few key words. These key words have been collated from each organisation’s website and listed in Table 4.1.

Interestingly, repetitions of words were noticed, for example, ‘customer’, ‘cost-management’, ‘hardworking’, were amongst the few words used by multiple organisations as their corporate values. These key words may be indicative of the current operating philosophies of these organisations.

However, one key word, ‘collaborate to compete’, sounded quite distinct. As can be seen from the Table, all other key words are more straightforward, having one single objective for example ‘partnership’, ‘teamwork’, etc., but it is the key word ‘collaborate to compete’ which has a two-step objective – such as bringing diverse functional teams together to focus on a shared purpose (PMCCB 2010).

Key challenges faced by organisations

We asked our organisations to list key challenges faced by them during the post-2008 economic downturn. These are listed in Table 4.2.

Table 4.2

Key challenges faced by organisations (n = 50)

| Rank | Key challenge | Response(%) |

| 1 | Cost cutting/budget freeze | 86 |

| 2 | Ensuring cash flow | 70 |

| 3 | Employee engagement and continuity of trust between employers and employees | 62 |

| 4 | Searching for new clients/venturing to different geographical locations | 42 |

| 5 | Work-life integration | 6 |

| 6 | Evergreen industry not affected by recession | 6 |

| 7 | Organisation producing niche products/services hence not affected by recession | 2 |

| 8 | Did not face any challenges – prepared to face to recession | 2 |

| 9 | Saving resources for future | 2 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

Of the nine challenges given, the top trio was by far the most commonly enunciated. These were:

1. how to and how much to cut costs and how to handle situations that occurred due to budget freezes on the client side (given by nearly nine out of ten);

2. ensuring cash flow (over two-thirds);

3. matters related to employee engagement and continuity of trust between employer and employees (nearly two-thirds).

The fourth most frequently listed challenge was exploring, or intending to explore, newer geographical locations given market saturation (42 per cent). In the case of Singapore, market saturation has become a serious threat to the long-term survival of organisations, especially many SMEs (which are mostly owned by ethnic Chinese). This market saturation is very much a consequence of the domination of the domestic market by foreign MNCs and SOEs during the industrialisation process in Singapore (Rodan 1989; Yeung 1994).

The other five challenges listed followed well behind these four, given by very few organisations (just 2 per cent–6 per cent). For example, better work-life balance (by 6 per cent) took a back seat as both employers and employees perceived such practices to equate to a loss of productivity and to be unaffordable in a crisis situation. This development is contrary to the perception that employers, as well as employees, had in early 2008, just before the crisis hit. For example, a 2008 report noted managing work-life balance as one of the key future challenges (Boston Consultancy Group & World Federation of Personnel Management Association 2008). Another example is that only a very few organisations (just 2 per cent) mentioned that even though others in their industry faced a lot of pressure from the adverse external conditions, their niches were not affected, their top management was proactive enough to cushion their organisations from becoming affected, saving at the same small percentage, seeing resources for the future as a key challenge. Thus, there were no pay cuts, retrenchments or other cost-cutting initiatives. Interestingly, such actions in turn boosted the morale of their employees and helped the organisations retain or attain a good brand image. These aforementioned trends were quite similar across most industries and size of organisation in our sample, barring those in the healthcare and security services areas. These two fields witnessed higher demand for their products and services, so were somewhat unaffected by the post-2008 economic downturn.

Reasons for unsustainability of businesses

It is noted that: ‘sustainability is currently one of the most fashionable terms used by post-Marxist Progressives. The word sustainable has been slapped onto everything from sustainable forestry to sustainable agriculture, sustainable economic growth, sustainable development, sustainable communities and sustainable energy production’ (Devall 2001: 1). If sustainability is such a widely referred to and well-understood term, what could be the reasons for unsustainability? When we asked our organisations for reasons, the following five were cited: poor leadership (by a huge four-fifths), resistance to change (over two-fifths), not being a ‘systems’ thinker (nearly a half), ignoring risk (just over one-third) and greed (over one quarter) as shown in Table 4.3. These reasons are discussed next.

Table 4.3

Reasons why organisations become unsustainable (n = 50)

| Rank | Key reasons | Responses (%) |

| 1 | Poor leadership (including bad governance, lack of vision, bad decisions/inability to make decisions, poor planning, etc.) | 80 |

| 2 | Resistance to change | 68 |

| 3 | Not being a ‘systems’ thinker | 46 |

| 4 | Ignoring risk | 34 |

| 5 | Greed | 28 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

As has been noted: ‘Poor leadership was on display after Hurricane Katrina and during the financial crisis. The New Orleans masses who huddled in the Superdome after Hurricane Katrina, the Enron retirees who lost their life savings and the laid-off workers buried under the economic ruin of financial companies all live with a simple truth. Just as spectacularly as great leadership can spark success, failed leadership can bring down cities, businesses, and economies’ (Lytle 2009: 26). The vast majority, four-fifths, of organisations believed that the rise and fall of any organisation had a direct correlation with leadership ability, and particularly attributes related to institutionalising good governance, vision, decision-making ability and planning.

Research indicates that organisations are undergoing major change approximately once every three years, whilst smaller changes occur almost continually (CIPD 2005). There are no signs that this pace of change will slow down. In this context, managers have to be able to introduce and manage change to ensure the organisational objectives of change are met and they have to ensure that they gain the commitment of their people, both during and after implementation. At the same time managers often also have to ensure that business continues as usual. The second most common key reason for problems, given by over two-thirds of our organisations, was resistance to change.

Implementing strategic change is one of the most important undertakings of an organisation. Successful implementation of strategic change can reinvigorate a business, but failure can lead to catastrophic consequences, including an organisation’s collapse (Hofer and Schendel 1978). Organisations and business preference often maintain the status quo, thereby ignoring the necessity to change and adapt to shifting conditions, which is yet another reason for unsustainability. For example, the 2010 Toyota product recall is an indication to the fact that the organisation failed to change internally with respect to its fast business growth, consequently affecting its current and future prospects. For example, ‘Quite frankly, I fear the pace at which we have grown may have been too quick. We pursued growth over the speed at which we were able to develop our people and our organisation. I regret that this has resulted in the safety issues described in the recalls we face today, and I am deeply sorry for any accidents that Toyota drivers have experienced’ (in Puzzanghera and Muskal 2010:1), said Akio Toyoda, the President of Toyota in a statement acknowledging his company’s inability to change with the pace of growth from its global expansion.

Organisational sustainability can be achieved through adapting to changes; although an organisation can only adapt through the changes when people in the organisation believe in the worthiness of the change and channel their energy in a single direction. Sustaining through people is, thus, the key organisational sustainability. We can see this in the example of AP Communications, as noted in the text box below.

Systems thinking has been defined as an approach to problem solving, by viewing ‘problems’ as parts of an overall system, rather than reacting to a specific part, outcome or event and potentially contributing to the further development of unintended consequences. Systems thinking is not just one thing, but rather a set of habits or practices. It is as if people of different opinions, thoughts and values are sailing a boat and discover holes in it when many of them are less bothered than the rest as the holes are not at their end of the vessel. Since their opinions are divided and priorities are different people spend their time disagreeing and opposing one another’s opinion, leaving the boat to sink while they are unaware of it. Just like the people on the boat, organisations whose cultures do not promote unified thought and actions are vulnerable to sinking. Many of our organisations, nearly half, indicated the tendency of ‘not being a systems thinker’ or lack of systems thinking culture in the organisation as the third major reason for business unsustainability.

Forrester (in Rasmussen et al. 2007: 15) argues that risk ignorance results in an ‘iceberg of risk’, where the full risk exposure of the organisation is underwater and cannot be seen. A lack of executive commitment to risk management is a primary contributor to the relative immaturity of risk management in many organisations. While the involvement of senior management is arguably critical to the success of any initiative, it is absolutely essential for risk management. The reason is simple – certain aspects of risk management run counter to human nature. When an organisation attains the highest level of maturity it typically requires that dedicated resources for risk management be integrated into business processes through a formalised procedure. However, many organisations have grown an internal maze of assessments as individual responses to various risks while omitting or misaligning the strategic risk (Maziol 2009). Ignoring risks or risk ignorance is the failure of an organisation to recognise that a risk exists. Risk ignorance as a reason why businesses fail was the fourth major reason, given by just over one-third of our organisations.

Greed is an excessive desire to acquire or possess more than what one needs or deserves, especially with respect to material wealth. Freud argued that greed was natural, that man was born greedy and that tendency had to be socialised (Coutu 2003). Krugman (2002: 1) noted that the notion that ‘greed is good’ for society may contain a fatal flaw as: ‘A system that lavishly rewards executives for success tempts those executives, who control much of the information available to outsiders, to fabricate the appearance of success. Aggressive accounting, fictitious transactions that inflates sales, whatever it takes.’ Greed was the fifth major reason for problems, given by over one-quarter of our organisations.

Key measures taken

There is no escaping the harsh reality that organisations faced during the post-2008 economic crisis. Essentially, organisations had the choice to react in three different ways: offensive; defensive; do nothing. Organisations that did nothing to adapt to the changing environment and waited for the business environment to stabilise were the most vulnerable when compared with the rest. The key measures taken by organisations ranged between being defensive to offensive. In terms of our organisations, the nine measures given are listed in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4

Key measures taken by organisations (n = 50)

| Rank | Key measure | Responses (%) |

| 1 | Cost-management | 86 |

| 2 | Focus on customer delight | 82 |

| 3 | Talent management and succession planning | 72 |

| 4 | Focus on innovation and identifying niches | 57 |

| 5 | Regular communication with employees | 52 |

| 6 | Focus on learning and development and getting ready for future | 14 |

| 7 | Constantly monitoring market conditions | 14 |

| 8 | Efforts to keep products and services affordable | 2 |

| 9 | Efforts to learn from the past | 2 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

The top trio of measures taken by our organisations were: cost-management (nearly nine out of ten); focus on customer delight (over four-fifths); and talent management (nearly three-quarters). The next most important set of measures taken by organisations were: focus on innovation and identifying niches (well over a half); and regular communication with employees (given by just over a half). The number of organisations using other measures then fell substantially. These were: focus on learning and development and getting ready for the future (less than one-sixth); and constantly monitoring market conditions (less than one-sixth). Indeed, the final two measures were given by very low numbers of organisations and concerned efforts to: keep products and services affordable (just 2 per cent); and learn from the past (just 2 per cent). We revisit some of these findings in more detail next and supplement them with further earlier research.

About nine out of ten of our organisations concentrated on cost-management through a series of procedures, reports and monitoring expenses. Efforts were made to manage investments, control variable costs and explore opportunities for savings. When asked whether cost-management was critical only during troubled times like recessions, some organisations stated that in good times competition can inflate labour costs. For example, companies in their rush to attract talent in the right place and at the right time had to increase their compensation structure so as to make it look more lucrative than their competitors rewards. Competitors then joined this ‘race’, in turn leading to wage cost inflation. Of course, some forward thinking strategies to retain people during recessions (see later examples), would assist in helping better control such trends and short-term behaviours (see Rowley 2010a).

The economic recession challenged organisations to maintain business operations while budgets were shrinking. Organisations were concerned that this could result in more negative customer sentiment. Many (over four-fifths) of our organisations provided additional services to delight customers and retain them. For example, some organisations maintained contacts and regularly sent appreciations of their support.

A large majority (nearly three-quarters) of our organisations identified talent management and succession planning as key measures. This is a key, integral HRM policy and practice area.

Maintaining R&D investment levels for organisations during a recession can obviously be difficult, yet it is precisely such a commitment to R&D that can be essential to an enduring competitive edge. As pointed out by the Director of Tourism for International Markets, Innovation Norway: ‘It does not need to be anything big, it could be small scale. You have to challenge how things are working. But standing still is much riskier than changing’ (Travel Weekly (UK) 2009: 1). Many of our organisations, well over a half, focused more than they did before on innovation and identifying niches.

Many (over half) of our organisations increased the frequency of communication with employees. For example, a giant food and beverage company in Singapore started organising ‘chit-chat’ sessions to gather feedback from employees on their work environment, policies and people matters. Similarly, a large telecom company initiated two-way conversations using social media. As the Managing Director, Marketing and Communications, Citi Global Wealth Management notes: ‘In difficult times, employees may display fears about losing their jobs; be cynical or suspicious about management’s motives; and demonstrate a loss of confidence in the company’s overall health. As employees were critical to all communications efforts, as their conduct and confidence affected both other internal as well as external stakeholders, it was imperative that they were actively engaged’ (in IPRS 2009: 1).

How organisations reacted to the post-2008 crisis in relation to employees can also be seen in an earlier research and a survey (SHRI 2008) – shown in Table 4.5. This also supports some of our research. While organisations note six measures, ranging from retrenchment to training employees for the future and looking at alternative arrangements for retaining jobs, no single measure was particularly common.

Table 4.5

Company reactions during the post-2008 economic crisis (n = 635)

| Rank | If your company’s business is not doing well in times of economic downturn, what will your company do? | Responses (%) |

| 1 | Retrench employees | 34 |

| 2 | Cut costs | 30 |

| 3 | Freeze wage increases | 18 |

| 4 | Internally train and prepare employees for the next economic boom | 14 |

| 5 | Sub-contract employees to other companies | 3 |

| 6 | Outplace employees and help them start their own business | 1 |

Source: Adapted from SHRI (2008)

As we can see, even the top two reactions were only mentioned by about one-third of organisations – these were to retrench employees (just over one-third) and cut costs (under one-third). Nevertheless, the economic crisis lowered demand for products and services, which impacted on employment as retrenching employees became a more common measure. However, the practice of employee retrenchment is a double-edged sword.

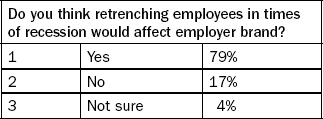

On the one hand, it helps to ease an organisation’s cost pressure; on the other hand it may badly affect the employer brand. This problematic impact was given by nearly four-fifths of organisations in other earlier research and a survey (see Table 4.6). Of course, there are other important impacts too.

In terms of other reactions by organisations in the survey (SHRI 2008), less than one-fifth mentioned freezing wages, and less than one-sixth training and preparing employees ready for the upturn. There were very few instances of the other measures. For example, very low numbers (just 3 per cent) of organisations noted sub-contracting of employees to others or outplacement and helping start their own business (just 1 per cent). Nevertheless, we can note some examples of these later measures. For example, as noted during a SHRI networking event, a Japanese MNC in the electronics manufacturing sector introduced the interesting practice of sub-contracting their employees or encouraging them to set up their own businesses related to the company’s products and to be a party to the company’s value chain. Another Indian IT services MNC offered employees opportunities to work with a non-profit organisation for a year while receiving half their salary. Through such practices these organisations were trying to better ensure that they were retaining their talent pool and keeping in touch with their employees, even when times were bad. These organisations believe such activities are futuristic in nature; enabling them to portray their loyalty to employees, breeding commitment, strengthening employer brands and helping to retain their talent pool. In short, these organisations believe that one of the best ways to manage talent is to be compassionate in times of need and establish an emotional bond with employees. Importantly, such low figures (as shown above) also need to be seen in conjunction with the earlier points, such as complaints about wage cost inflation, and are a clear indication of the costs of short-term views by organisations.

The remaining measures taken by our organisations were far less common, and ranged from less than one-sixth concerned with either learning and development and getting ready for the future or monitoring markets; down to just 2 per cent making efforts to train and/or remain afloat.

Risk management strategies

Risk management is the active process of identifying, assessing, communicating and managing the risks facing an organisation to ensure that our an organisation meets its objectives. Some of the key measures that organisations started taking during the post-2008 recession also featured in their list of risk management strategies (see Table 4.7).

Table 4.7

Risk management strategies adopted by organisations (n = 50)

| Rank | Risk management strategy | Responses (%) |

| 1 | Cost-management (including producing cost-effective products/services, better inventory management and control) | 92 |

| 2 | Talent management and succession planning (including training locals to reduce dependency on foreign workers) | 80 |

| 3 | Focus on innovation and operational excellence | 62 |

| 4 | Exploring new market segments | 40 |

| 5 | Constant focus on cash flow | 12 |

| 6 | Reducing cost of energy and exploring alternative sources of energy | 6 |

| 7 | Forming strategic partnership/mergers/ acquisition | 6 |

| 8 | Knowledge management initiatives | 2 |

| 9 | Introduced business continuity plan | 2 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

Cost-management (noted by over nine out of ten), talent management and succession planning (four-fifths) and focusing on innovation and operational excellence (nearly two-thirds) are by far the top three risk management strategies adopted by our organisations in order to remain sustainable. We detail further aspects of these findings next.

By cost-management organisations meant better inventory management and control, reducing wastage and producing cost-effective products and services. Cost-management as a risk management strategy was by far the most commonly noted and was clearly ranked first, as most (over nine-tenths) of our organisations mentioned this.

In many parts of the world, talent management and succession planning has been one of the prominent agendas for organisations, including those operating in Asia. This area includes the idea of training locals to reduce dependency on foreign workers. We can see similar attempts in the Middle East, such as trying to make better use of graduate women (Rowley et al. 2010). Low fertility rates and an ageing population, as in many countries, prompted many organisations in Singapore to open their doors to more foreign workers, as we noted in earlier chapters. By February 2010 foreign workers comprised almost a third of Singapore’s total workforce (AFP 2010). This increasing dependence on foreign workers, coupled with socio-economic changes such as an ageing workforce, led to recent changes in legislation. Singapore is taking action to slow down the hiring of foreign workers by raising the FWL. As the Finance Minister said: ‘We should moderate the growth of the foreign workforce and avoid a continuous increase in its proportion of the total workforce. There are social and physical limits to how many more (foreign workers) we can absorb. But instead of imposing quotas, the government will raise the levies paid by companies for every worker they hire. This allows the foreign workforce to fluctuate across the economic cycle and enables employers who are doing well and need more foreign workers to continue to hire them rather than be constrained by fixed quotas’ (AFP 2010: 1).

Such an increase in the FWL will have an immediate impact on labour-intensive industries, such as the marine sector, construction, etc, which hire large numbers of foreign workers. While industry associations are regularly in touch with the government to further discuss the challenges and seek help, many organisations, especially in the marine sector, have started training locals to reduce dependency on foreign workers, but this will take some time to work its way through. As such, this situation highlights some of the issues of allowing unrestricted migration in terms of creating ‘moral hazard’ and actually encouraging organisations not to invest to train and upgrade their human capital, workforce and business. Some four-fifths of our organisations gave the risk management strategy of talent management and succession planning.

Due to the small market size in Singapore, economies of scale are important for commercial viability of capital intensive businesses (MDA 2008). With limited internal consumption power and controlled markets, the local market is relatively smaller than in many neighbouring nations. In order to balance small market size and increases in productivity, many organisations focus on innovation and operational excellence. For example, Singapore Airlines is one of the companies that has been profitable every year since its inception. It achieves such a feat by improving operational excellence through some of the tactics like continuous training of its employees, consistent and continuous internal as well as external communications, and so on. The airline is also known for its innovative new approaches to customer engagement, like fax machines on board, ‘book the cook’ services for special meals in First and Business class, phone, fax and e-mail check-in, to list just a few (Kaufman 2010).

Various initiatives are being taken by the government to promote innovation and operational excellence among organisations. For example, SMEs in the manufacturing sector seeking to raise productivity and capability are able to benefit from the recently launched ‘SME Manufacturing Excellence Programme’. This was designed and developed by the Agency for Science, Technology and Research’s own Singapore Institute of Manufacturing Technology (SIMTech) to groom a pool of process improvement champions or ‘Techno Vation Managers’. The programme aims to train managers in operations management innovation (OMNI). With knowledge and skills acquired from the programme, SME managers can help raise productivity and improve business and operational excellence within their companies. In addition to undergoing classroom training, trainees have the opportunity to apply the OMNI methodology to address specific operational challenges in their companies, under the mentorship of SIMTech’s trainers. Companies sending their managers to the programme enjoy 70 per cent course fee funding support, plus an absentee payroll (AP) grant from the Workforce Development Agency (WDA), a statutory body under the Ministry of Manpower, Singapore. The AP grant helps companies defray the costs incurred when they send employees for training. From 2009 the AP cap for training courses under the Skills Programme for Upgrading and Resilience was revised upwards to a single rate of S$10 per hour, which translates to a maximum AP claim of about S$1,600 a month per worker (MOM 2009: 1). Over the next 2–3 years WDA and SIMTech aim to train a pool of 150 such managers to champion and lead operational improvements in their organisations (ACN 2010). Nearly two-thirds of our organisations listed the risk management strategy of focus on innovation and operational excellence.

Apart from the above trio of strategies, the fourth risk management strategy our organisations listed was: exploring new market segments and trying to reach out to newer geographical territories (by two-fifths). Beyond these four risk management strategies, the remaining five were not that commonly given by our organisations. A constant focus on cash flow was noted (by less than one-eighth), but very few of our organisations were either reducing energy costs and looking at alternative sources (only 6 per cent), or forming strategic partnerships and M&A (6 per cent), with even fewer of our organisations introducing business continuity plans (just 2 per cent) or knowledge management initiatives (2 per cent). This last strategy’s very low level is very surprising given the importance of the latter area and its critical role in the development, upgrading and adding value of businesses and economies (Rowley and Poon 2010a).

Future challenges

Business sustainability seeks to create long-term shareholder value by embracing the opportunities and managing the risks that result from an organisation’s TBL of economic, environmental and social responsibilities. Thus, business sustainability can be described as the application of knowledge, skills, tools and techniques to the organisation’s activities, products, and services in order to accomplish an organisation’s vision and mission.

Regardless of how large or how profitable they are, many organisations are inextricably linked with the societies in which they operate. This is not least because every decision they make, whether it is to close a plant, relocate operations or develop or set a price for new products, will eventually affect the surrounding community and the natural environment, for better or for worse. Furthermore, many MNCs use emerging markets as a part of their production chain, which is especially true for the Asian economies (Korhonen and Fidrmuc 2010). The global economy is driven by increasing technological scale, connections between firms and information flows (Kobrin 1997: 147–8) and is one ‘with the capacity to work as a unit in real time on a planetary scale’ (Castells 1996: 92).

In this increasingly wired world, organisations operating in one part of the world impact on others even though they are geographically located far away from one another, even in other continents. Thus, on one hand the business world has become ‘glocalised’ – having the ability to think globally and act locally, while on the other hand the number of variables affecting business sustainability has multiplied, making it more complex than ever before.

By and large organisations perceive the future to be uncertain. Having identified nine key challenges (see Table 4.8) that they think will affect their businesses over the next five years, organisations are looking to find suitable solutions. We detail these further next.

Table 4.8

Greatest challenges for organisations over the next five years (n = 50)

| Rank | Greatest future challenges | Responses (%) |

| 1 | Talent management | 86 |

| 2 | Understanding customers’ expectations | 72 |

| 3 | Leadership development | 62 |

| 4 | Innovating new products and services | 58 |

| 5 | Financial viability | 46 |

| 6 | Venturing into new market | 40 |

| 7 | Business transformation and developing new business model | 34 |

| 8 | Manage and motivate employees | 18 |

| 9 | Energy usage and waste management | 4 |

Source: SHRI (2009)

There are three socio-economic forces driving possible talent shortages: demographic decline in many nations; a skills gap because students and workers are not receiving the education and training needed for high-tech employment (human capital issues); and a cultural bias against undertaking the rigorous educational preparation needed for scientific or technical employment (Gordon 2009). It is no surprise that talent management tops the list of challenges that the vast majority (nine in ten) of our organisations foresee.

With globalisation and frequent inflow and outflow of consumers from one geographical location to another, the customer landscape has become more challenging for organisations and doing business. Adding to this are new social media like Facebook, Twitter etc. and forms of networking between customers. Customers keep getting connected, but often more to each other than those that they buy from (IBM 2010). This situation requires the formation of a bond between the customer and the provider. Hence, understanding customer expectations is going to be one of the critical challenges for organisations in the future. The challenge of understanding and meeting customer expectations was noted by nearly three-quarters of our organisations, the second most commonly noted issue.

The talent crisis may lead to the slower growth of an organisation due to unfilled positions, but a shortage of leaders with the right abilities can cause a firm’s demise. Leadership development is also a challenge elsewhere in Asia and around the world (see Rowley and Poon 2010b). One study notes that about two-thirds of the companies surveyed said the lack of leadership talent was having a moderate to major impact on their ability to achieve business goals (Executive Development Associates 2005). Some additional consequences of such shortages include increased spending on recruitment and training and the intangible costs of poor decision-making as companies fill positions with people who are less qualified. In fact, leadership development is another significant challenge for our organisations, and indeed was the third most common, noted by nearly two-thirds.

With high customer expectations, innovating new products and services will remain a challenge for organisations. Indeed, this issue was given by well over half of our organisations, making it the fourth most common challenge.

While investing in R&D for new products and services, organisations also expect challenges to ensuring financial viability. This issue was given by under half of our organisations, the fifth most common challenge.

With highly competitive local markets and market saturation, organisations will have to look beyond local geographical borders to venture into new markets. Indeed, two-fifths of our organisations expect to face issues related to this, making it the sixth most common challenge.

These challenges include identifying and understanding new markets, assessing the feasibility of doing business there, arranging initial capital for such expansion, getting people on board with skills suited to such new markets and more. These trends will require the development of new business models. Indeed, just over one-third of our organisations noted this, making it the seventh most common challenge.

A business in transformation is complex to manage. Adapting to new business conditions requires a pool of motivated employees who will have trust in the organisation and firm belief in its direction. Yet, post-2008 downturn employees have become more sceptical about business decisions. Thus, organisations may anticipate a challenge in restoring such beliefs to surge ahead with a team of motivated employees. Less than one-fifth of our organisatons mentioned such issues, making it the eighth most common challenge.

It is often asserted that energy usage and waste management will be one of the greatest future challenges for organisations. It is interesting to note that only a very small number of our organisations (just 4 per cent) listed this issue, making it only the ninth challenge. Is this low position due to ignorance or contentment? Or could it be that organisations are yet to catch up with the ‘going green’ mission? Whatever the reason, it is a somewhat surprising result.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have examined organisational views and business sustainability in terms of: core values, key challenges, reasons for unsustainability, measures taken, risk management strategies, and future challenges. What we found was that business sustainability still seems to be a maze for many organisations. Irrespective of their size, the organisations covered in this book vary along the sustainability continuum, of between not being sustainability aware to mature sustainability leaders. Though many organisations are aware that adopting practices balancing the 3Ps of people, prosperity and planet dimensions will help them ensure greater business sustainability, they are often stuck in the quagmire of achieving just-in-time, visible and countable benefits and hence short-termism and its consequent behaviours and actions, which may come at a cost, not least the long-term survival of the organisation and types of HRM practices, are adopted.

Interestingly, there were many key HR issues mentioned by our organisations. These included the key challenges faced, where two of the nine were key HR-related issues – ranked third (by 62 per cent, employee engagement) and fifth (by 6 per cent, work-life balance); while two of the nine key measures taken were HR-related issues – ranked third (by 72 per cent, talent management) and fifth (by 52 per cent, employee communication). Of the nine risk management strategies, two were HR-related – ranked second (by 80 per cent, talent management) and eighth (by 2 per cent, knowledge management). Of the nine future challenges, three were HR-related – ranked first (by 86 per cent, talent management), third (by 62 per cent, leadership development) and eighth (by 18 per cent, managing and motivating employees). These findings echo earlier, similar, research (SHRI 2008) where all six reactions of organisations to economic crisis were HR-related. The critical role of HR to organisations remains unabated and even seems to be more important as a result of the impacts of the post-2008 economic crisis.

The next chapter illustrates some of the innovative, sustainability-oriented practices adopted by some organisations, including in HRM. It also provides an integrated framework and suggests a road towards a more sustainable future.