Chapter 2

Replacing the Sun: A New Solar System

The conductor of an orchestra doesn't make a sound. He depends, for his power, on his ability to make other people powerful.

—Benjamin Zander

Remember when you passed your driver's test and received your license? It was an indescribable feeling of joy, freedom, fear, and excitement all rolled into one. This is the feeling many successors have as they take over a firm from a founder or group of founders. Removing the founder from the day-to-day operations of the firm has an emotional impact on everyone involved: the founder, successor, employees, community partners, and, of course, the clients. We deal with the emotional aspects of this transition later in the book, but in this chapter we focus on the operational risks successors and founders need to evaluate in their transition.

The founder-centric firm, so common in the advisory space, creates a challenge for the successor in assessing the organization and what it needs to grow. The successor and founder should start with one question: Are we replacing the old model with a new model or are we just placing a new person at the center of the solar system? The answer to this question has major ramifications throughout the organization, and for its employees and clients.

What Road Do You Choose?

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

—Robert Frost

This idea of choice continues to guide our thinking. Since the three of us are “glass half full” people, we read this ending and believe the “difference” made is a positive one. Most people likely read the poem and interpret it in a positive way. However, cynics will say there's no clear answer. Maybe the other road is less traveled for good reason; there may be great dangers ahead. Founders are often not only choosing a road but clearing the land to lay the beginnings of a road—a safe passage to a destination not yet seen. By the time the successor comes along, he or she is in a position to level the road, perform maintenance, and often lay pavement to expand the capacity it can handle.

Firms choosing to remain independent and build a second and then further generations of leaders, have two roads in front of them. We believe that the “road highly traveled” leads down a path where the founder is simply substituted at the center of the firm's solar system. The founder copies his or her role description and just hands it to the successor. The processes of the firm and the skill sets of the people are not reassessed, and changes (improvements) to the client experience are not at the center of the transition. Many firms believe this is a viable approach, and for some firms it is. It has the benefit of being least disruptive in the short term. It maintains continuity around people and the business model. However, in our opinion, this short-term continuity can create significant longer-term challenges. It's the “if it ain't broke, don't fix it strategy.” As in the story of the little Dutch boy, Hans Brinker, who put his finger in the dike to stop a leak, this is not likely to be a permanent solution. Tomorrow's problems are always lurking behind the distractions of today's busy schedule. We believe short-term thinking in the operational components of transition can lead to longer-term challenges for both successors and founders. These longer-term challenges impact the ability to monetize the business, enhance the client experience, and successfully transition the firm to future leadership.

The “road less traveled,” where the client experience, staffing decisions, and new growth opportunities are addressed, is hard. It's especially so on the successor as the one being tasked first with maintaining and then growing and improving the business. In many cases the founder has already reduced his or her workload and it's easy for a successor to get trapped in a rut of just trying to get daily tasks accomplished. Successors may believe they are heading down the road less traveled, but if they don't follow a deliberate operational approach to the transition, they can easily be detoured to the first, highly traveled road, without even noticing. We believe the hard work of choosing the more onerous short-term path leads to a company with better prospects for growth, with a culture that can recruit and retain top talent, and one that is better poised to achieve good outcomes for clients, employees, and the firm's owners as well.

Committing to the Road Less Traveled

If the founder and the successor have chosen to take the longer-term view, what's next?

As a successor, you may already be an owner in the firm or are about to become an owner and operator of the firm. Now what do you do? The first step is to evaluate the involvement of the founder. Is the founder going to be involved in the day-to-day management and operation of the business? Is the founder going to transition to a new role immediately, or over some period of time? The speed at which you must assess the client experience, organizational processes, and staff resources will differ based on the transition period. If the founder remains involved, don't worry too much. Take your time and get it right, but be very clear about where the ultimate authority lies. And be sure that the founder has an adequately engaging area of responsibility so he or she doesn't even inadvertently try to reoccupy his or her former space. If, instead, your founder truly retires, turn on an old Road Runner cartoon and take some notes; you have no choice but to dig right in.

Figure 2.1 provides a framework in which to evaluate the operational needs of the business.

Figure 2.1 The Operational Assessment Process

Assessing the Client Experience

The Founder or the Firm?

The successor needs to assess the operational significance of the founder. To do this, start with one dominant perspective: not your own, not the founder's, but the client's perspective. How does the client view the firm? How do the processes work to serve the client? Are there repeatable, documented processes in place, or did everything rely on the patterns, opinions, talents, and relationships of the founder?

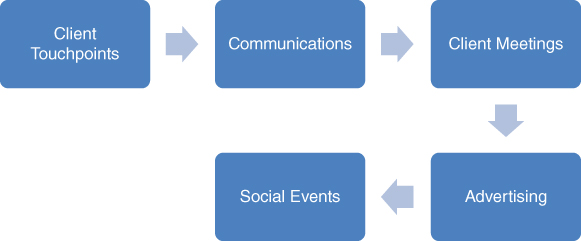

We believe there are a number of steps a firm should go through to assess the client experience. This process is laid out in Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Assessing the Client Experience

The Supplemental Materials to this book include a form that helps to catalog all of the firm's client touchpoints. The key through this entire assessment is to ask four main questions: Who? When? Why? How?

The client communication assessment step tells a firm a lot about where it is in transition. We believe a successor needs to review all the touchpoints with a client. Who schedules meetings? How are they scheduled? When newsletters and other communications go out, under what name are they released? Whether you have a founder-centric firm or a client-centric firm will become obvious. If all communications have come out under the founder's cover, you haven't transitioned the firm in the eyes of the client. You can always tell the stage of transition the firm is in and how hard it could be on the successor by looking at the last five general client communications.

Eric agrees that communications are an appropriate start, and he cautions: “This operational assessment is tough work, but it's important. You need to realize no detail is too small. We had a very detailed process which started with something as small as a newspaper advertisement.” John Henry McDonald was the founder and the face of Austin Asset. He brought in almost all of the clients. He was on the radio and was the voice of the company. To make the point that this might need to change, Eric began to talk with John Henry about the firm's advertisements. Since its founding, Austin Asset had run advertisements with a picture of John Henry and his dog. People saw the ads, maybe recognized his name from the radio, and would call the company. This is where Eric started to worry. As John Henry began transitioning away from the business, what was the receptionist going to tell the prospect? John Henry isn't here? John Henry will call you back? Let me put you through to someone else? It was not a small detail. It could become a big issue in the day-to-day operations of the business.

Over time, the firm transitioned its marketing. The first step was to retain the picture of John Henry and his dog but add the other members of the firm. The final step added the logo and a picture of all the advisors, but did not include the names of any individual advisors in the ad. This took time because it carried an emotional weight, but Austin Asset needed to show prospects that the entire firm, and not just the founder, had something to offer. Similarly, market outlooks and newsletters, quotes in the newspaper, articles written in trade publications, and conference speeches all have important impacts on the business's ongoing success through a transition. The founder has the ability to endorse others in the firm and elevate their visibility.

Eric shares this story: At his first industry conference with John Henry, he was invited onstage during the preparation the night before the presentation. He had been with the firm for a couple of years, but had never been put in a position like this with the founder and another industry veteran (David Drucker). Much to his surprise, the next day he was included in the actual live presentation on career paths and from that day forward was encouraged to share his story with other young practitioners. This endorsement also helped back home at the firm. He was starting to develop his own voice, under the guidance of his mentor/founder.

Tim's case was different. He had always been the “voice” of the firm, authoring or editing virtually every word that Aspiriant or Kochis Fitz had published and being the primary spokesperson to media and the industry. He continued in that role to design the firm's transition communications, but then choreographed his own obsolescence as the firm's voice, promoting a greater public presence for Rob Francais and replacing his editorial role with a fresh editorial committee.

It's Show Time—The Meeting Strategy

In the advisory space, most of the client experience comes down to the in-person meeting with clients. Founders of successful advisory firms love client meetings—they're like a show. A lot of work goes on behind the scenes that clients don't fully appreciate because they don't see it. This puts a lot of pressure on the advisors and support staff to represent the firm's brand when they are onstage. As most successful founders of advisory businesses are really very good at selling and love being onstage, looking at the client meetings and how they will work during and after the transition is one of the most important operational decisions a company makes.

The Agenda: All successful meetings have an agenda, but in the transition process who sets the agenda for client meetings? The answer is simple in some firms, but complicated in others. Both Eric and Jay set the agenda in their respective firms. Both believed it was a good step in the learning process, especially when taking on new responsibility for the relationships, to review past meeting notes to see if they could zero in on what the client really was interested in. Jay believes taking an extra step helps to encourage a growing relationship with clients. “I believe in all cases, but especially when you are trying to build a new relationship, you should call a client or prospect two weeks before the meeting, give them some preliminary thoughts you have on the agenda, and ask them what they want included. It goes a long way to show you are prepared, are empathetic, and are genuinely interested in meeting the client's needs. It certainly gives you a better chance of having a good meeting.”

Train Wrecks to Avoid

The next step is to determine whether the founder needs to review the agenda with the successor in advance. We strongly encourage this during the transition process. The founder and successor should not only understand the subject items but also assign who is going to speak on which topics. In some cases, the founder may no longer be attending every meeting with a client. Sometimes a founder doesn't want to take the time to review the agenda or the materials. The successor or someone else in the firm is now the day-to-day relationship manager and understands the issues and the client's goals for the meeting.

The successor relationship manager and the founder enter the meeting room. Two things can go awry. The first train wreck involves the founder bringing up a “hot topic” that had already been resolved at a previous meeting, making the founder, and the firm, look out of touch. How do you think that makes a client feel? The person they have trusted for many years to look after them suddenly appears to be out of the loop.

According to Tim, this potential problem is completely controllable. As the firm grows, primary client service responsibility transitions need to take place, client by client, long before the founder steps away from the overall leadership of the firm. You need to make sure the client understands there is someone looking after the details. Tim explains: “This may no longer be my responsibility as much as it was before, but I need to be transparent and honest with the client. I can't have it both ways. I either have control of the relationship and therefore must be all over it, or I need to tell the client I am there to support and mentor the successor client relationship manager. Often, perhaps, I'm not going to know all of the details, but the successor will.”At first, this can require a leap of faith in the skills of the new manager of the client relationship; for a founder, it takes humility.

Another potential train wreck can have more long-term ramifications for the firm. We'll describe this problem as “does not play well with others.” It can be hard for the founder to refrain from stepping back in where he or she left off and dominating an entire meeting. Eric describes how it feels when a successor watches this in real time: “Founders have built very successful businesses, in many cases with them virtually doing everything. They are wired to continue that; and they step into the meeting and dominate it. As I would watch it happen I would think to myself, this doesn't do any good for our transition. Successors have to be prepared and work hard to command the agenda items most important to the client. It's easy in the beginning to feel apprehensive. You may not present things same way as founder or present them as well. You and the founder, both, have to learn to be okay with this reality.”

At Austin Asset, Eric and John Henry went through role-playing exercises. That role-play didn't start with the meeting; it started the moment the client walked in the door. Eric walks us through his thought process: “I was worried about the little details of relationship building. Should I greet the client? Should John Henry? Should the receptionist just sit them in the room? We worked really hard to transition relationships and to have clients feel comfortable about John Henry not being their day-to-day relationship manager. If a client spent the first 10 minutes catching up with John Henry on the weather and other small talk, that's one thing. In a supportive role to the team, he could do what he did best: relate to anyone and make them feel welcome. However, sometimes clients would talk hard details and then John Henry would find himself knee-deep into a planning topic without really wanting to disrupt the process. For founders it is through no real fault of their own or bad intention. These skills are what attracted the client to them in the first place. But this overexerted strength of their own can become a weakness for the business transition. It takes a brave successor and a self-aware founder to replace this client reliance.”

Other details that both Jay and Eric analyzed were: Who was in the meeting and how should the room be configured? Both of them believed the person heading the meeting should be at the table or located in the room in a way that made it obvious to the client that this person was in charge of the meeting. Founders and successors need to have a plan before the meeting. Let's get very practical and lay out what we think is an effective way to handle this subtle interaction.

For instance, if the founder greets the client and has a pleasant two- or three-minute interaction and then endorses the “new” client lead before walking into the meeting, the stage is set for a positive transition of client responsibility. The founder escorts the client to the meeting room, where the “new” lead is positioned at the head of the table, with the founder maybe at the side of the “new” lead. The “new” lead welcomes the client and builds rapport before taking the lead in conducting the meeting with a clear agenda. The founder's role is to support the advice of the lead and, as the meeting closes, might offer a comment like this: “Joe will be following up with your next steps and action items. I will be only a phone call away, but look to Joe first for any follow-up questions you have.” Then the follow-up e-mail traffic begins, and the founder is copied on all of it. As the next meeting approaches, the successor can take the next step. At that next meeting, the “new” client service lead can greet the client at the outset, with the founder's speaking role restricted to the meeting itself, planned only to add color or perspective and perhaps close the meeting with an empathetic question. One of John Henry's great closing comments was: “Are we doing what you would have us do for you?” It demonstrated concern that he genuinely cared that the client was being well served through the transition to a new advisor.

Taking the Long View

The decision at Austin Asset not to put John Henry and his dog in the newspaper was a risky proposition in the short term. Eric worried. What if the phone quit ringing? This is where very real conversations can occur, and should occur, about expectations. “In our case I was a minority owner and the reality was that John Henry made the call to pull the picture from the ad. We certainly talked a lot about ‘why’ this was important for him, for me, for the firm and for clients we didn't even have yet. The tide changed and we found the phone rang more than it ever did before.” The beauty was that now John Henry didn't have to work with every person who called. John Henry could close business like Mariano Rivera, Major League Baseball's all-time leader in saves. Tim Kochis could as well. Most successful founders can close at high rates. If they couldn't, they wouldn't have a business to transition. But to have the founder continuing to close all the business means that others aren't learning how to do it—they are being given the fish rather than learning how to fish for themselves.

Good businesses grow. As Section II of this book examines, a firm's growth rate is one of the most important variables driving at its equity value. The long-term track record of the firm matters more than a short-term decline or a positive spike. This economic reality is easy to understand academically, but for a firm in transition it can be difficult to deal with the idea of a short-term pullback in growth. As the successors and their team take on the responsibility of generating new business, a firm hopes the growth rate will increase and stabilize. The growth rate in the first year of a transition often drops. This is driven by two key factors. As a founder-centric firm shifts its brand, fewer prospects may come in the door, and the close rate of the successor may not be as high as the founder's was. Further, the operational work we discuss in this chapter is important to rebuild the foundation for the firm's future. That can be extremely time consuming, leaving less time and energy, in the short term, for business development efforts.

Austin Asset conducted a very relevant conversation during its time of transition. With the desire of the growth-minded founder focused on business development and the successor intent on building a system that could sustain itself, John Henry and Eric had to get on the same page. The “help” of more new client activity was actually “hurting” the business. Eric went to John Henry and said what must have sounded blasphemous to say to a natural rainmaker: “The best thing you can do right now is not bring in any new clients.” Why? Because the firm was in the middle of an entire service model revision centered on three pillars of progress—a new client experience, an ongoing retention experience, and a new staff compensation model.

- New client experience: How would we screen potential clients? How would we schedule those that were a fit? How would we manage the meeting? What roles would the team play? What would the founder's role be?

- Ongoing retention: How often would we meet? What would we offer at those meetings? How would we prepare for those meetings? What roles would the team play in those meetings (if different from those listed in “New Client Experience”)? How would we handle quarterly reports or other communications with clients?

- Compensation: Does it matter which clients you specifically work with? Would it be team oriented or production based? How would we reward a collaborative model where clients belong to the firm? How would we structure a model with a competitive base and team-focused incentives, aligned to the organization's overall strategy?

It really does little good for a founder and successor to bring a high volume of prospects in the door if new processes are not yet in place to match or, better, improve the client experience. According to a 2014 Schwab benchmarking study, 75 percent of all new business in financial advisor firms comes to the high-performing firms through referrals. So bringing a prospect in the door for a bad experience can really hurt the brand of the firm. For a while during the transition, a firm needs to be more internally focused. Short-term pullbacks in growth are okay. Nevertheless, founders and successors need to have a discussion about how long they are willing to accept that slowdown. If you allow the transition to drag on, it's easy to lose focus on external relationships and all the other things needed to build a growth-oriented culture. Firms that stay internally focused too long don't grow.

Welcome to McDonald's: May I Take Your Order?

One of the University of Notre Dame's legendary Knute Rockne's most famous lines was “I find prayers work better when I have bigger players.” Our advisory businesses are built on our advice. Advice is delivered by people. If logic holds, then better people and better advice produce a better-performing firm. As a successor, there is nothing more important than making the right people decisions. This is obvious on paper but difficult in practice. Charles Goldman, one of the financial industry's most experienced observers and most insightful thinkers, sums it up: “Building the best business you can…the best people…the best processes…will make your transition much easier. Through the transition process people often lose sight that in the end it's about building a better business.”

One of the hardest things successors have to do is assess the people they inherit. Depending on how long the successor is in place at the firm, he or she may have been involved in hiring most of the people. Most successors inherit at least an employee or two as the “legacy” hires of the founders. A common theme throughout this book is the respect due to founders for taking the risk to go on their own and create a business, often largely from nothing. It takes a special kind of person to do this. It also takes a healthy ego and strong self-confidence. This confidence leads to success in building the business, but it can cause problems in many areas during the transition. The people element is one area where problems often lurk.

Despite good intentions, founders' egos sometimes get in the way of making optimal people decisions. We've seen two types of founders. The first type hires people smarter than themselves and lets those people excel. The reason many transitions don't work is that too many founders are in the second category. They love being the center of attention and insist on being the smartest person in the room. This pride in being the best causes them to surround themselves with lower-performing employees, rewarding loyalty and deference instead of high performance. These firms tend to have hired “order takers” rather than self-initiators. They sit at their desk and wait to be told what to do. Which kind of founder the firm has had should give you a good sense of the kind of people you have inherited.

Human Capital Framework

The Supplemental Materials provides a framework that is focused on the people involved in the firm. This supports a systematic process for the firm to go through to make logical decisions about their people. People decisions are hard. A key finding from the 2014 Schwab benchmarking study is that the fastest-growing firms believe that what brought them to their current level of success is not enough to take them to the next. This almost certainly includes at least some of your people.

Question #1: Would you hire this person again, knowing what you know today?

Jay reflects on this question: “I've made some bad hires. I think we all have at some point in our career. I went back over the bad hires I've made and they all raised the same thought: I wish I could go back and not hire that person. I realized when assessing existing organizations: Why not force yourself to ask this question to bring clarity? If you wouldn't hire someone again if given the chance, should they really be on your team?”

Question #2: Is the person meeting the expectations for their role today, and whether they are or not, can they learn and grow into rising expectations?

Every high-performing organization should have expectations for each role. If people aren't meeting the minimum expectations today, should they be around? The response to that question from an operational viewpoint is simple. How about three years from now? We live in a service economy. The client experience is the focus of every service organization. Clients know this and continually increase their expectation of what a good client experience looks like. Advisory businesses are no exception. The expectations of service delivery increase; consequently, the performance expectations for your people need to increase with it.

Having a culture that fosters raising the level of performance is important and can be accomplished only if that is a part of your performance appraisal process. The performance appraisal process does not need to be complex. Larger organizations often have a formal human resources program to manage this. Smaller firms may merely meet casually with employees once a year over lunch. Whatever works for your firm is fine so long as a “better than average” performance today becomes only “average” performance three years from now, and average performance today may be considered an unsatisfactory level at some time in the future. One way to begin to get this across is to have employees list their top 10 accomplishments each year as part of a self-appraisal process. This allows you to see how employees view their roles, what's important to them, and what they are proud of. If you do this each year you can compare the accomplishments, year over year, to see if their positive impact on the business has increased.

Question #3: Is this person the best person I can hire for the job?

No matter the size of your firm, best-in-class organizations have best-in-class people. This question is more subjective than the other questions in the framework. What does “best in class” mean? Like beauty, it's in the eye of the beholder, but here are some simple situations to consider. Do you ever rave about your employees at an industry event or cocktail party? When you go to conferences and hear the speaker, do you ever think that your people are as good as or better on the substantive topic or in their presentation skills? If so, you probably do have the best in class.

However, this exercise raises a further question: Do all of my people need to be best in class? Best-in-class talent is expensive. Why should I pay top dollar to have best-in-class people in every position? The next filter helps assign weights to the first three questions in the framework.

Question #4: Is the position critical?

We believe a company should have a culture where all roles are rewarded and equal amounts of appreciation are given for jobs well done. However, leaders all know certain roles are more important than others. A receptionist is further down the food chain than your lead business development position. We recommend that successors rank each position in order of importance: critical, important, or replaceable. This can help bring clarity to the first three questions. If you mark a position as important or replaceable but not critical, you likely don't need someone who is best in class in that position. You may be able to deal with someone who just meets general expectations for the position. It's very important to ensure you are putting dollars and management attention toward hiring and developing best-in-class talent in the areas most critical to the client experience and thus to the long-term success of the business.

Question 5: Now that you've completed the matrix, what's next?

For those classified as “Wouldn't Hire Today,” it's critical for the management team to determine what drives that classification. If the person works hard but is not a cultural fit because of the changes in the firm, the person still deserves respect for his or her efforts. If someone can't seem to get out of bed in the morning and get to the office on time or ignores client requests, it's a very different decision.

During transitions, leaders really do have to make sure they handle people in a way that enhances the culture regarding accountability that they are trying to build for the future. This may be especially true for those who are best in class. Without appropriate acknowledgment and rewards, you risk losing some of your most valuable assets. Most advisory practices are built on their human capital. We must invest in our staff as our form of research and development.

A central piece of the transition plan at Austin Asset was to create development plans for all employees, including the owners. These plans were designed to take one employee's individual role at the firm today and build a parallel path for that employee consistent with the strategic plan of the firm. Eric puts it this way: “It is great to have a plan to grow your firm, but will the employees grow along with the firm or will you have to hire replacement talent along the way?” Employees' development plans can focus on short-term personal and professional growth that feeds directly into the person you desire to have in three years. As time passes, you can assess the employee's actual personal development with the strategic plan of the business, making course corrections along the way to gauge how connected the strategic plan for the business is to the key ingredient in your client service offering, the firm's employees.

Improvement Matrix

The Supplemental Materials include an accountability matrix. As the successor takes over more of the daily activities of running the firm, processes and people will likely need to change. So much of the work used to be completed by the founder; as the founder is pulled away from the day-to-day activities, mistakes are going to happen. Using this matrix, a successor, along with the help of the others involved, can determine if the mistake was caused by:

- Company Problem: The firm is lacking a process to complete the task or the process is not designed properly. A good question to ask in this area is: If no matter whom I put in the situation would have failed, do I have a process problem? The answer is yes. If the transmission was put into a car where “R” actually meant forward, it doesn't matter who the driver is; the driver is going to fail.

- Skills or experience: In the transition process, people are going to be asked to get outside their comfort zone. It's important to assess if mistakes are being made because there's a lack of experience or a lack of training.

- Execution Problem: People can get by for long periods of time by going through the motions. However, there are many times when the process is sound, the training is sound, and a person just doesn't get the job done. That's fine in certain cases, as mistakes happen, but if someone continually doesn't meet your expectations, you have to question whether they should stay around.

Hire Slow. Fire Fast.

—Harvey Mackay

Emotions are often extremely high when it comes to keeping people or letting them go. However, don't make the mistake of taking people who are not really suitable for their roles and creating new roles for them unless it's obvious the organization needs those new positions. Do not forget the key items from earlier in this chapter. Assess the client service menu and experience. Assess the processes and roles needed to deliver on the goals of the company and those of the clients. Then decide on the right people to accomplish that. Doing the assessment in this order helps founders and successors focus clearly on the end result. People who don't really fit the process or delivery of the firm's goals for client service and business growth are simply not a fit for the firm.

The transition process can strengthen the culture of the business or it can fracture it. Nothing is riskier for the operational culture of a business than the way a firm decides to reward its people or let them go. Allowing underachievers to stay at the firm makes it difficult to raise the performance expectations for the business as a whole. Firing people too quickly or ungracefully can result in a gloom-and-doom environment for the new management team. But, done right, and with appropriate rewards for the “survivors” and with worthy new hires, an upgrading of the firm's people can set a very positive tone for future success.