Chapter 3

Transforming Your Practice into a Business

Assessing What You Have Built

There is a clever use of terms and concepts in this industry such as describing the organizational structures of independent financial practices as “silos” or “ensembles.” The basic notion is that a silo is a single book of business. The term ensemble is reserved for an actual business with multiple professionals who truly work together as a team, pooling their resources and cash flows, creating a bottom line, and then distributing profits to the owners of that business.

Silos can exist as part of a group, or they can exist as stand-alone offices, but effectively, they each have their own books of business regardless of the employment or compensation approach. Almost every one of the advisors we’ve ever worked with technically falls into the silo category. Even most of the advisors who have been around for 30 years or more and own fast-growing limited liability companies (LLCs) and call themselves ensembles are most often a group of silos. That has been our firsthand experience year after year. In fact, if we restrict our discussion to advisors with a value of $25 million or less, those for whom we have seen the data and that comprise most of the independent industry (at least in terms of a head count), we come across just a handful of true ensembles every year, out of thousands of engagements—that’s it.

Still, these terms have been very useful in that they have focused attention on what you are building, and how you are building it. We couldn’t agree more that correct structuring is critical to building an enduring business model; building the foundation is the prequel to the succession planning process. In his book The Ensemble Practice ( John Wiley & Sons, 2013), Philip Palaveev made this statement: “When you arrive at the conclusion that you want to build an ensemble practice, you will find that hiring professionals with less experience and helping them grow into lead advisors is perhaps the most reliable and most available path to building an institutionalized, valuable, large firm.” And he’s absolutely right.

Let’s build on that point and take stock of what you’ve accomplished to date. What have you built? One of the points we’ve consistently tried to make in this book is that, as an independent owner of what you do, you need different and more appropriate tools to work with than you’ve been given. To help you assess your position and to help you set your goals for the future more accurately and explain them to your stakeholders, we think a simple and intuitive shift in terminology will aid in the process. Consider these time-honored labels and the industry-specific descriptions that follow as guides for determining where you are today, and where you’d like to be five or 10 years from now:

- A job

- A practice

- A business

- A firm

We’ll be the first to admit that these categories, as described in more detail next, will need to evolve and become better defined through actual usage over time, but here’s a good starting point as to how these practical labels seem to break down in our experience:

- A job exists as long as you, the advisor or financial professional, do it. You are independent, and you own what you do, for the most part. It is your “book.” Whether W-2 or 1099, registered rep or investment advisor or insurance professional, it makes no difference—they can all fit equally well under this category. But when you stop and someone else starts, it’s their job to do, not yours, and the cash flow attached to that job belongs in whole or in substantial part to the person doing the job. Of course it is about production; in fact, it is about nothing else. You work under someone else’s roof, you own none of the infrastructure, you have no real obligations to the business other than to produce and get paid while taking care of your clients. The value of a job is tied almost entirely to how much money the producer or advisor takes home every year. There is no need for a succession plan or a continuity plan. You don’t sell a job; you leave it.

- A practice is more than just a job, often involving support staff around the practitioner and basic infrastructure owned by the practitioner (phone system, computers, customer relationship management [CRM] system, a payroll, etc.). But like a job, a practice exists only as long as the practitioner can individually provide the services and expertise. Practices are limited to one generation of ownership, and then someone else takes over—the practice is sold, or the practice is dissolved and the clients find their way to another advisor. Practices have one owner, whether formally in an entity structure or informally in terms of control over the client relationships (a book). The value of a practice typically is limited to about $1 million for a variety of reasons. The focus is entirely on revenue strength; there is little need for enterprise strength at this level. The primary succession plan is attrition, followed in second position by selling to a third party. Continuity agreements are rare, and life insurance is the primary solution, at least for the practitioner; the clients are on their own. There is little or no bottom line, and there doesn’t need to be—no one invests in this model.

Here’s where the bigger shift occurs. If the engine of production (the means of making money) rests solely or primarily in your hands and you cannot or will not change that dynamic, then you cannot build an enduring business that will outlive you; if that is the case, you own a job or a practice. A business, if that is your goal, is designed to make the founder replaceable at some point, even as the business continues on. - A business must have certain foundational elements in place: an entity structure, a proper organizational structure, and a compensation structure that give it the ability to attract and retain talent and additional advisors who enable this model to outlive its founder. A business is built to be enduring and transferable from one generation to the next and, as a result, is more likely than not to have an internal succession plan fueled by multiple owners from multiple generations. It operates from a bottom-line approach, and earnings, for the first time, begin to reward ownership and investment in the business. Many businesses still bear the name of the founder, and are working through compensation issues and the effects of revenue-sharing arrangements and are prone to creating competitors rather than collaborators, though they see the problem and are taking steps to try to address the challenges; the leadership is aware. Culture is increasingly important, though many businesses find that they may need to adjust and adapt to a different culture in the future. Continuity agreements are common and take the form of a shareholder agreement or a buy-sell agreement. The value of an independent financial services or advisory business ranges from at least $1 million up to about $10 million. A business gains its momentum and cash flow from revenue strength, and its durability and staying power by developing enterprise strength.

- A firm is an established business, but in addition, it has achieved its value in excess of $10 million, at a minimum, by building a strong foundation of ownership and leadership by recruiting and retaining the very best people in the industry. A firm has multiple generations of ownership with key staff members vying for an opportunity to earn the right to become a partner and invest in the firm. It operates primarily from a bottom-line approach, and earnings are the measure of success, at least as important as production and growth rates. Profit distributions are the variable portion of an owner’s compensation. Continuity agreements are a given, and the firm assumes the natural ability to weather the deaths or early retirements of its current leadership group over time. Collaboration among owners and staff is the rule. A firm emphasizes company-wide coordination of decision making, a group identity, teamwork, and an institutional commitment. The goal isn’t to have the best professionals, but rather to have the best firm. Getting into a firm as a new hire is difficult. New hires not only must have the requisite skill set, but they also must fit into the culture and help it to thrive even as they work hard to support everyone around them.

In this book, from this point forward, when we use terms like practice or business or firm, those terms will be used specifically and within the context of the preceding definitions. We think the independent industry, in terms of a head count, fits into each of these categories approximately as illustrated in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1 Four Industry Categories

Remember that while this is an industry with a relatively high average age, the typical level of production or revenue generation per financial professional or advisor at the major independent broker-dealers, custodians, and insurance companies is less than $200,000 per year—in many cases, much less. These professionals represent an incredible opportunity for business builders and for one-generational practices that need a second generation of talent to work with, mentor, and plan for, or even possibly just to acquire.

It really depends on what your end game strategy is: What do you want your practice to do for you as you grow older? Do you want to build a business that can provide you with a lifetime of income and benefits and purpose? You do have a choice, if you build with the right tools and execute a sound plan with the right goals in mind.

A Building Problem, Not a Planning Problem

Advisors are not planning for succession and failing—they’re not planning at all. And why would they? This is an industry of one-owner jobs and practices that were never intended to grow into enduring businesses (ensembles) or firms (super-ensembles as they are sometimes called). Planning alone cannot fix a structural issue, or worse, a series of structural issues. In fact, planning is not the problem; building is the problem. Once we collectively improve on the assembly methods and the tools, building valuable and enduring businesses will be as natural and normal as, well, providing long-range, multigenerational financial advice.

The wirehouse tools that have been borrowed as building implements by advisors place no value on business building and never had use for equity management in a cash flow only environment. As a result, most advisors and financial professionals don’t even try to set up a formal succession plan—the thought never even occurs to them. If your goal is to progress from a job or a practice to an enduring business, you first have to build an organizational structure that can withstand the test of time. It isn’t that hard to do, but it is best accomplished as part of a comprehensive plan, and ideally, well before designing and implementing your succession plan.

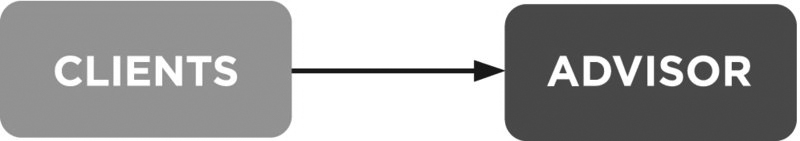

The common starting point for most advisors is a sole proprietorship model—a single advisor compensated on the basis of some form of revenue-split or eat-what-you-kill (EWYK) system, often working under someone else’s umbrella. It resembles Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Basic Organizational Structure

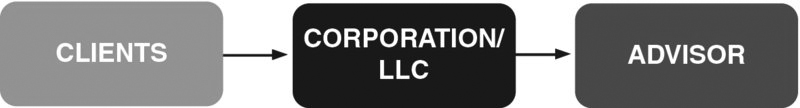

This basic production-based or advisor-driven model is extremely adaptable and simple to establish and operate. If this model is set up with any type of revenue-share or EWYK (short for “eat what you kill”) system, it is all about owning a job. Over time, as the competitive elements begin to outweigh the collaborative attributes, advisors progress from owning a job to owning their own small practice, and it looks more like Figure 3.3.

Figure 3.3 Basic Organizational Structure

Unfortunately, these common starting points are often mistaken as building blocks for larger, more sustainable business models; it appears to be as simple as doubling the cash flow by doubling the number of producers. In a wirehouse model or even in an independent broker-dealer, custodian, or insurance company, this is exactly the way it works and has for a long, long time. This results in a very common and predominant business structure in the independent financial services industry illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Figure 3.4 Individual Books Organizational Structure

This structure, for years generically described as a “silo model,” is what we call a “practice,” which is exactly what it is. A practice presents one common business name and structure to the advisor’s clients and to the public, but the nucleus of the model, the corporation or limited liability company (LLC), has little or no value because only expenses are paid through its bank account. The value, or equity, is actually split between two or more advisors, each a separate, isolated production unit or book capable of taking his or her clients with him or her at any time.

From a buyer’s perspective, the practice as a whole, certainly the entity itself, has no value. Adding more and more advisors to this model may increase total cash flow, but it usually does not change the resulting equity value of the founder’s operations. This is the classic one-generational model that most advisors build almost intuitively.

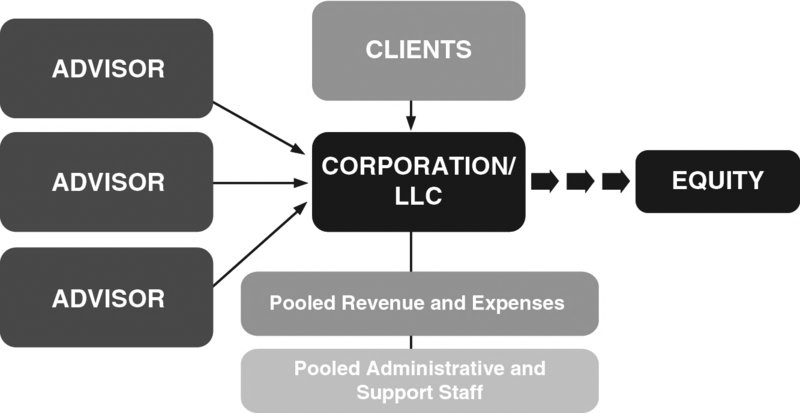

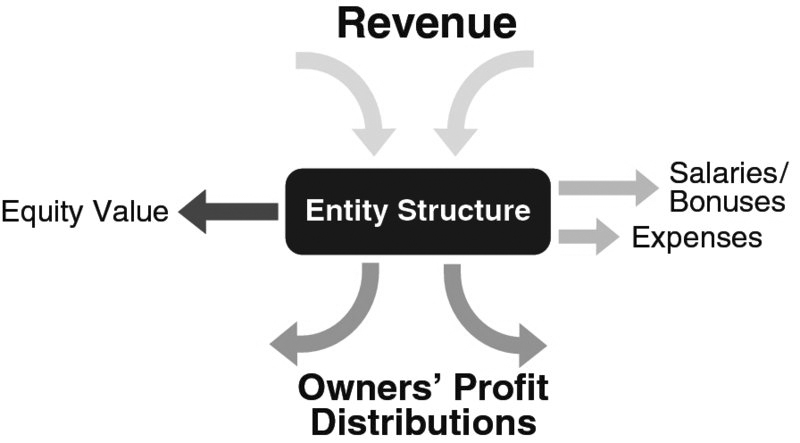

The most valuable and enduring business models now emerging in the independent financial services industry are structured like Figure 3.5. This is a diagram of an independently owned business. It relies on a strong, centralized entity structure (LLC or corporation), which collects all incoming revenue (assigned from the receiving producer/financial advisors), pays out compensation (wages and benefits) for work performed (including production), and pays operating expenses. Controlling these top-line costs results in a bottom line, or profit distributions, and these profits, in turn, provide each equity partner with two essential results: (1) a return on the partner’s investment, and (2) for new owners, the means by which to pay for that continuing investment. These results are why and how next-generation advisors invest in a more valuable business rather than building their own individual books.

Figure 3.5 Equity-Centric Organizational Structure

So, why would a highly compensated producer who receives, for example, 50 percent of everything he or she brings in want to see a change in the organizational structure toward enterprise strength and away from revenue strength? Quite honestly, he or she may not. You didn’t hire, train, or compensate your best producer to think like a bottom-line investor in your enterprise, and these folks often are paid as much as or more than most owners, with little or no risk of investment. Does that mean you have to jettison highly paid producers in favor of lower-paid, less capable producers? Of course not.

Our experience has been that about 85 percent of next-generation advisors/producers choose to physically and financially invest in being an equity partner in a business or a firm when it is offered. The rest? They already are paid and treated like owners; why sign a promissory note with a payment obligation and take the risk when the benefits of ownership have been freely offered for years? Discouraged? Don’t be—there are ways to solve the problem, but the importance of your organizational structure cannot be overemphasized, or compromised. Here is another way to think about it that many of our clients have found useful and interesting.

A Parable

Consider this parable to better understand the organizational challenges most advisors face when trying to progress from a job to a practice, and ultimately to a business of enduring value over the course of a career:

Picture a bright orange life raft floating on a dark blue, storm-tossed ocean. In this durable, well-built small craft sits an independent financial advisor. Our advisor has a paddle for propulsion, the means by which to move the raft to safer or more prosperous waters. Our advisor has the means to collect and store rainwater for drinking, and fishing tackle to bring in food for survival—the craft literally is floating on a sea of food and fuel to sustain and propel its lone occupant. Our advisor also has a compass for navigation to guide forward progress along a chosen route; or, if preferred, our advisor will just drift as the winds and current dictate. Both result in movement.

Over time, though the sea is vast, there are many financial advisors, and our advisor encounters other life rafts and other peers. Most of the time, they just pass by and coexist, easily and effortlessly competing for the same food supplies without much thought or concern. But in time, when the skies grow dark and the seas inevitably become more challenging and dangerous, behaviors tend to change. Instead of passing by each other, groups of advisors in their bright orange life rafts come together and form a group. Under the right circumstances, they’ll lash their rafts together for safety and support and form a consortium of three or four, each sitting in their separate crafts, but inextricably linked together for the duration of the event.

During this time together, our financial advisors can explore various opportunities. Synergies may develop from the group, as the paddles are placed in the hands of the strongest advisors whose task it will be to propel the group to safety. The advisor best qualified to lead and navigate will take the compass and direct the group with a single vision and set of coordinated actions. And the advisor best suited to “hunting and gathering” will be charged with collecting water for drinking and food in order to sustain the efforts of his or her crewmates—each doing what he or she does best, contributing to the success of the group. But it is just as likely that each independent advisor continues to function as a separate unit, each eating what he or she kills and each reserving the right to cut the ropes and paddle off at any time and in a direction of his or her own choosing.

One of the biggest mistakes that financial advisors continue to make is to view this group of life rafts as the pinnacle of business growth and organization, or even as the goal—as it is in most practice management circles. The mistake is to think of this loose assembly of individuals and producers as a ship when in fact it is nothing more than a flotilla, quick and easy to assemble, and equally quick and easy to disassemble. The wirehouse model and even the independent broker-dealer and office of supervisory jurisdiction (OSJ) models we currently have are poor blueprints for building a valuable and enduring advisory business.

Later in this book, we’ll talk about onboarding advisors with existing books and evaluating them as possible equity partners, and we’ll differentiate their contributions in terms of what they impact: cash flow or equity value, or both. Here is another useful way to think about these kinds of issues. Your business is the ship, and the advisor with a small book is in a life raft. In year one of the onboarding process, allow the life raft to tie up next to your ship, and to enjoy the shelter and safety and convenience your larger and more stable vessel has to offer. Over time, if the onboarding process goes well, the advisor may leave his or her life raft and find a permanent place on your ship, or, if the process does not go well, the advisor can get back into his or her life raft and paddle away. That’s what life rafts are built to do. Keep that in mind when you allow them to come alongside your ship and enjoy the efforts of your labors.

Building Your Ship

As we continue to evolve and fine-tune the more appropriate categories of building a job, a practice, a business, or a firm, let’s apply the lessons to be learned from the preceding parable. What are the practical differences between a practice and a business?

| The Life Raft Model | The Ship Model |

| About the best producers. | Group effort focused on the bottom line. |

| Focused on short-term goals. | Focused on short-term cash flow balanced with long-term equity growth. |

| Top-line revenue is the key. | Bottom-line profitability is the key. |

| The leader is the best producer. | The leader is the most experienced and capable advisor. |

| It’s only about production. | Owners don’t have the luxury of doing just one thing well. |

| The president’s pay is based on production. | The president’s pay is based on intelligence, leadership, and production. |

| One-generational. | Multiple generations of ownership create an enduring business. |

| Highly decentralized. | A valuable, central business owned by its advisors. |

| Eat-what-you-kill system is the norm. | Profit-driven culture, with profits available only to owners. |

| 1099 compensation structure. | W-2 compensation structure. |

| Entity has little or no value. | Entity has all the value. |

| Value is centered in each producer. | Advisors are paid competitive wages for their work; profits are for owners. |

| Focus is on cash flow, not equity. | Focus is on shareholder value. |

| Revenue strength is very strong. | Revenue strength is balanced with enterprise strength. |

| Ownership exists, but only of a book. | Individual books are not permitted or rewarded. |

| A competitive environment. | A collaborative environment. |

| Nimble and adaptable. | Decisions are made collectively. |

| Continuity plan is a revenue-sharing arrangement. | Continuity plan is an enterprise agreement (buy-sell). |

| Nothing and no one to succeed the owner. | Succession plan is an integral part of the business plan. |

| Easy to assemble and disassemble. | Requires professional counsel (consultants, lawyers, CPA, etc.). |

Building a ship is not for everyone, but more than 1 percent of the industry needs to do so—that is, needs to build enduring businesses. Think of it this way. If you own a job or a practice, you still need a continuity partner; you still need someone, someday, to step in and take over for you and to take care of your clients and their children and grandchildren, someone to pay fair market value and help you realize the value of one of your most valuable assets. Who better to do that job than the ship on the horizon? If you don’t want to build your own ship, then steer toward someone else’s when the skies become dark and the seas start to get rough; stay close to the ships out there. They can help in many ways and for generations to come.

Rethinking Your Compensation System

In this industry, we are firmly convinced that the early generations are building life rafts by accident; it is what advisors with a wirehouse background or training think they’re supposed to be doing, and honestly, they do it quite well. It is what advisors are told to do—that, and the simple replication of the models immediately available and obvious to every practice owner: independent broker-dealers, custodians, OSJs, branch managers, and the like. As you know, or as you’re quickly learning, independent models are unique and they require special attention and special tools and assembly methods during the foundational building process.

Simply stated, revenue sharing is a terrible compensation system for advisors who want to build a business. Revenue sharing or commission splitting or any kind of EWYK system has a seriously detrimental effect on where the value, or equity, is centered—either in the enterprise or business itself (which can endure) or in the individual producer or advisor (which is unlikely to survive beyond the advisor’s career). When compensation is tied exclusively to the top line, to gross revenue or total production, there is zero reason to aspire to ownership; there is no need to even hazard a glance at the bottom-line profits when you’re paid off of the top line. This is a great deal for nonowner revenue producers; they take little or no risk, working only the hours necessary to produce revenue, and they get paid like an owner. But that is not how to build a business.

Here is an example from a group we recently worked with:

Mark and Katie Dickson, husband and wife, operated a fee-based business in Boston, Massachusetts. The value of their 23-year-old business was determined to be $2.5 million, enough to fuel dreams of a comfortable retirement. Mark and Katie were well-educated and experienced owners and collectively held the credentials of CFP, MBA, and CPA, and Katie was an OSJ as well. They were each 50 percent owners of an LLC taxed as an S corporation. Mark was 58 when we met him; Katie was 54. Mark and Katie had two key employees, Karl and Christina, and together, they wanted to design and implement a 20-year succession plan that would allow Mark and Katie to gradually retire on the job starting in their mid-60s.

The business was flourishing in most respects. In addition to substantial business value, Dickson Financial Partners, LLC, enjoyed a strong annual revenue growth rate of 14 percent (an average over the preceding five years), and spent only 38 percent of its revenue on overhead, not including owners’ compensation. Payroll, occupancy costs, advertising, and information technology (IT) expenditures all benchmarked favorably against their level of competition. They performed annual valuations and tracked the growth of their equity value carefully.

Karl (age 39) and Christina (age 35) had no clients when they were hired by the business some years before. They were paid on a revenue-sharing arrangement and encouraged to “build their own books,” and build they did. Whether with Mark and Katie’s donated smaller clients or clients they found on their own, Karl and Christina managed to each build substantial recurring revenue–based books without ever having to invest or risk their own money in building an office or the infrastructure to support their production goals. And they didn’t really have to worry about much other than production, which contributed to the high, sustained growth rate of the enterprise. Mark and Katie took care of everything from staffing to the phone systems to the IT issues, all in exchange for 50 percent of the revenue Karl and Christina produced. What Mark and Katie didn’t pay attention to until too late was the equity value of the separate books.

Very recently, Mark and Katie were delighted to welcome Karl and Christina into the ownership circle and offered them each a discounted and seller-financed opportunity to become partners in the business, cumulatively buying 25 percent of their ownership in Tranche 1 of the plan. Karl and Christina were honored to be asked, but then responded with a series of unsettling questions:

- “Why would we buy our own books?”

- “How much stock are you granting to each of us in exchange for the books we’ve built?”

- “Why would we want to become minority owners and at-will employees when we already own and control our own books and income streams?”

Based solely on the production numbers, Karl and Christina would be 28.3 percent and 15.6 percent owners, respectively. Legally, they owned 0 percent of Dickson Financial Partners, LLC, but they were able to negotiate from a position of strength. They didn’t want to leave and set up their own practices, and in the end they didn’t have to. The deal got done and Karl and Christina ended up with 25 percent of the ownership of Dickson Financial Partners (worth $625,000), and a salary increase.

In the end, Mark and Katie realized that they had nearly made a $1.1 million mistake and created two potential competitors rather than two potential partners. Almost 45 percent of their cash flow could have walked away. Instead of selling a 25 percent stake in their business, they exchanged ownership for control over books they watched and enabled to be built.

Mark and Katie had managed over the years to retain 100 percent of the ownership and control of their LLC, but they failed to realize that they were slowly and certainly transferring away over a million dollars of that equity by saving money and using a simple revenue-sharing approach.

Balancing Revenue Strength and Enterprise Strength

Creating substantial and enduring value in a professional services business over the course of a career is a multifaceted challenge that will demand adjustments or improvements to a number of primary value drivers and support mechanisms. In addition to the more obvious elements of cash flow and incoming revenue, equity growth and management strategies also depend heavily on certain foundational elements such as the entity structure, the organizational structure, compensation methods and profit distributions, ownership tracks, and talent management initiatives—elements that speak to the strength and ability of an enterprise to grow and retain value over time.

By our estimate, 95 percent of advisors focus primarily or exclusively on revenue strength elements (the function of owning a job or a practice). The analysis of revenue strength covers an array of benchmarks, but focuses on the areas of revenue production, cash flow quality, pricing competitiveness, and efficiency.

Most independent financial services professionals and advisors understand how to build revenue strength (increasing the number of good clients and retaining those relationships); the challenge in making it to the enduring business level lies in building enterprise strength. Enterprise strength is a term we use to refer to a financial services business’s legal and organizational structure (including its compensation systems)—in other words, its infrastructure. Are the necessary people, tools, and resources in place to build and support an enduring and transferable business over time? Can the business survive and prosper after its founder’s retirement, death, or disability? Is it one valuable and enduring enterprise or many smaller, individual books that are just as likely to become competitors as collaborators?

Increasing both of these business components may seem like a sensible approach to increasing business equity, but the process becomes more problematic in achieving the end result over time. For example, increasing the number of clients and retaining those relationships as a business’s leadership ages may require a substantial investment in staffing, training, and operational capacity, while pursuing a strategy of significantly increasing the revenue generated per client may require a change in culture, deliverables, skill sets, and operational systems. In either case, any increase in revenue that is accomplished by emphasizing one strategy or the other does not directly correlate to an equal or proportional increase in the equity value of a financial services business, nor its ability to sustain the rate of growth and to realize that value upon transition.

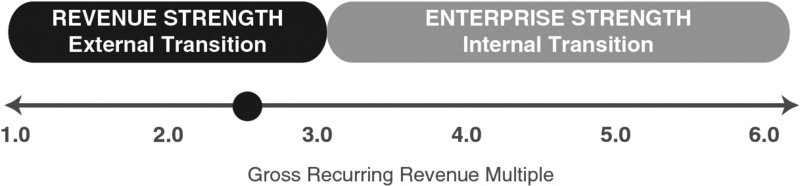

As a quick aside, ever wonder why there is such strong buyer demand for practices (today’s buyer-to-seller ratio is 50 to 1)? Imagine if you were selling your home and had that kind of demand, in just the first 10 days! There may well be a number of good reasons, but consider this: The average buyer tends to be two to three times the size of the average seller. Big is buying small, and the motivation seems quite logical. Practices (see the previous definition) have an inherent limit on value because of how they’re constructed. The highest value we’ve seen in the past several years, expressed as a multiple of gross recurring revenue, is just short of 3.0 times trailing 12 months revenue. The average multiple of fees or trails, as depicted in Figure 3.6, is 2.36 times trailing 12 months revenue. But businesses are more valuable; when sold internally, they tend to generate a much greater return, something in the neighborhood of 6.0 times trailing 12 months revenue based on the starting point of the plan, not including wages and benefits for the duration of the plan. Every dollar of revenue acquired from a practice and placed into a business with a balance of revenue strength and enterprise strength becomes worth far more.

Figure 3.6 Gross Recurring Revenue Multiple

Enterprise strength is not an elusive or difficult goal to obtain, if you know what you’re doing, but it is not a building step many practice owners concentrate on. That’s unfortunate, and that needs to change if your goal is to build a business of enduring and transferable value. Continue to focus on the concept of building a foundation for success before you begin the succession planning process. The three areas to focus on are your organizational structure, your compensation structure, and your entity structure. Having covered the first two earlier in this chapter, let’s focus on the final and most straightforward of these three foundational elements: entity structure.

Selecting the Right Entity Structure

Based on a steady stream of data from over 1,000 valuations per year, we know that eighty percent of advisors with values of $1 million or more are set up as an entity (S corporations or LLCs are the most popular models among advisors); above $5 million in value, close to 100 percent of advisors are structured as or make use of an entity. This is not a coincidence, as size and structure are directly related. Businesses require more than one person to run or administer them, and entities can accommodate that fact better than sole proprietorships or even teams. If you want to build a valuable and enduring business, set up a formal entity; that is step one in the implementation process and is a step best taken well in advance of designing and implementing your succession plan.

A sole proprietorship, or a corporation or an LLC with just one owner, will come to an end with the retirement, disability, or death of its owner; it is built to die. A corporation or an LLC with multiple generations of ownership serving multigenerational client bases, on the other hand, has the ability with proper planning and staffing to last well beyond any one advisor’s career or lifetime, and to create an enduring business with significant transferable value. This business value or equity, in turn, can support a variety of sophisticated succession plans for the founding owner and key staff members.

In this industry, we see the following structures used most frequently in the independent space:

- S corporation

- Limited liability company (LLC) taxed as a disregarded entity

- LLC taxed as a partnership

- LLC taxed as an S corporation

We come across some C corporations (occasionally as an LLC tax election) and a few general partnerships, but not in significant numbers. C corporations tend to be the entity of choice for older and larger firms (more than 20 years old and above $20 million in value—the 20:20 Club), but not so much for the practice models. We also set up and work with teaming arrangements that don’t involve the use of a formal entity (usually due to compliance issues within the broker-dealer or insurance company). For the most part, S corporations and LLCs are the predominant choices by advisors.

One of the keys to building an investor-worthy business, or at least one of the more straightforward routes, is the use of a tax conduit, because it helps to channel money to the bottom line, a function that solves a number of important building and compensation issues. C corporations can work, too, but most advisors we talk to with this entity structure channel all of the cash flow out as compensation to avoid double taxation, providing no return on investment to next-generation advisors.

For those of you who reside in the realm of the sole proprietor model on the advice of your tax or legal counsel, understand that the benefits of proper entity structuring reach far beyond liability and tax issues. Establishing an entity structure and using it correctly can provide an excellent continuity solution as well as additional long-term strategic planning opportunities. Utilizing an entity structure along with ongoing, annual valuations to monitor equity can help retain and propel the next generation of advisory talent, which in turn can perpetuate your business while providing you with an income stream for the rest of your life. These common goals are almost impossible to achieve through a sole proprietorship.

One of the major advantages for owners who operate as an entity is the ability to transfer or sell small, incremental ownership interests to next-generation staff members, and create two or more owners of one financial services business. For example, a founding owner can set up an internal ownership track and gradually sell 5 percent, 10 percent, or 25 percent of the business to one or more key employees, paid for over many years in a series of tranches while retaining control, a process that is part of FP Transitions’ “Lifestyle Succession Plan,” explained below. The ability to create multiple owners in one enterprise, as you’re learning, is the perfect antidote to the revenue-sharing, individual book-building approach that has created an industry of one-generational practices.

Note: Even though an entity cannot be paid securities revenues under Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) rules, almost all independent broker-dealers permit advisors to contribute their earned revenues into a corporate bank account that pays expenses, including salaries. To be on the safe side, all owners should be properly licensed in order to participate in these structures and to receive profit distributions. Fee-only Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) are a different matter, and are typically a little easier to work with in this regard. If you’re FINRA licensed and you’re not sure, check with your compliance department beforehand.

What You Need to Know

When deciding to form a business entity, attorneys and accountants tend to focus on two primary factors: (1) limited liability and (2) taxes. We’d add a third factor: (3) business perpetuation. For independent advisors, the limited liability portion of this equation is less important than for other business owners, because the prevalent liabilities are customer complaints and regulatory actions. The limited liability benefits of an entity structure will most likely not protect you in either case; this is why financial professionals often carry errors and omissions (E&O) insurance. However, limited liability can protect you against other potential business liabilities, such as creditors or accidents that occur on your property. Businesses with solid earnings histories may be able to execute an office lease with the entity being the lessee, rather than the principal of the business.

The tax issue is more complicated, but also more to the point of this discussion, which is why a CPA plays an important role in every succession plan we design. Most owners don’t set up an entity solely for the tax savings. The broader issue is one of cash flow and tax efficiencies for both founder and next-generation owners (which we’ll cover in more depth in the next section), but think of it this way. A sole proprietor has but one way to get paid, and then at the highest tax level on that ordinary income payment stream. An S corporation, for example, has two ways to pay its shareholders (wages and profit distributions), but three ways to build wealth when you also include payments to the seller of stock of that S corporation, especially over many years from a group of active next-generation owners (what we call “the succession team”) as the business continues to grow, and at long-term capital gains tax rates. Again, the key is equity, and there are some incredible tax efficiencies that are a part of most succession plans and all of them benefit from an entity structure of some type.

The one factor that most attorneys and accountants overlook is the issue of perpetuation—the ability to build something that can outlive you. A sole proprietorship or a one-person entity simply cannot accomplish this task. You need a structure that next-generation advisors can take ownership of, very gradually over the course of a career. Entities are built to do exactly that.

In terms of selecting the right entity type or understanding what you currently have, start with this basic premise: Most advisors will benefit from a flow-through model, or tax conduit—think an S corporation, or an LLC taxed as a disregarded entity, a partnership, or an S corporation. Why does this matter? Recurring predictable revenue has more advantages than you may realize—it also provides recurring, predictable overhead, which means you can run the cash flow model on a leaner setting than just about any other professional services practice or business. In other words, you can take more money home because it is easier to know how much, or how little, you can leave in the bank account. Flow-through entities are not built to retain earnings. If you’re a next-generation advisor looking for a way to pay for the stock you want to acquire, that is a very good thing because all future growth dollars in a properly structured cash flow model will stream to the bottom line (after expenses, of course), where they will be discharged in the form of a profit distribution check to each owner. For these reasons and more, most choices come down to a basic S corporation or an LLC.

Before we go into specifics on these two primary choices, it is important to understand that selecting the right entity structure isn’t just about what’s best for you right now or as you build your business; it is also about what is best for your future owners. It is all about building a sophisticated vehicle to help every owner build wealth by building a single, strong, equity-centric business. In the process, don’t confuse complicated with sophisticated; you do not need one entity for every half-million dollars in revenue to build an enduring business. Keep your entity structure simple and understandable; later, we’ll add and define a new and relevant term in this regard: investor-worthy.

If you’re looking for a more direct answer and you’re not yet in an entity structure, here it is: Choose the LLC. It can evolve with you and your business, and it can support virtually any succession plan you or we can design. It also can provide some important tax benefits when onboarding talent into an ownership position.

Limited Liability Companies versus S Corporations

Limited liability companies are relatively new on the landscape. Corporations have been in existence for hundreds of years, whereas LLCs did not come into existence in the United States until 1977. Despite the late start, almost 45 percent of today’s independent advisors who have an entity structure have chosen the LLC format, and there are many good reasons for this choice. Lest you stop reading now and settle on the LLC as the best choice and be done with it, you’re going to miss an important point: You have to learn to think in two dimensions to fully understand and utilize the LLC structure, and that’s where the S corporation comes right back into play as an important consideration. For that reason, you need to understand how both models work.

LLCs are a hybrid that combines features of a corporation with the operational flexibility enjoyed by partnerships and sole proprietorships. An LLC is often a more flexible and fluid structure than a corporation, and it is well-suited for a practice that starts with a single owner and progresses to a business with multiple owners. An LLC has the unique ability to elect to be taxed as a sole proprietor (or disregarded entity), a partnership, a C corporation, or an S corporation; in other words, you get to choose your tax treatment. (Sadly, electing no tax treatment is not yet an option!) Further, an LLC with multiple owners or members that elects to be taxed as a partnership may specifically allocate each owner’s or member’s distributive share of income, gain, loss, or deduction through its operating agreement on a basis other than the ownership percentage of each owner or member, something an S corporation simply cannot do.

An S corporation must distribute earnings and/or losses according to ownership interest. For instance, if you have two owners, one who is a 75 percent owner and one who is a 25 percent owner, the earnings and losses must be divided 75/25. There is no exception. However, in an LLC taxed as a partnership, the earnings and/or losses can be split however the owners agree in their operating agreement. For example, if the ownership interests are again 75/25, the owners can agree to split the earnings or losses 50/50, or any other manner in which they agree, and they can change it from one year to the next as a matter of contract. S corporations allocate profits and losses as a matter of law. Although an S corporation has to pay distributions strictly according to ownership interest, owners can effectively adjust this aspect of the cash flow by paying compensation (think salary and bonuses) at their discretion.

Any person or legal entity can own shares (usually called units or membership interests) in an LLC, and there can be any number of shareholders (called members) or classes of stock or ownership, depending on the tax treatment. LLCs can have deductible employee pension plans for both owners and nonowners. In most states, LLCs taxed as a partnership lose their W-2 status and are subject to self-employment taxes.

S corporations are corporations that permit flow-through income taxation. Every corporation actually starts as a C corporation. To obtain S corporation status, the corporation has to file an election with the Internal Revenue Service. With an S corporation, you may be able to reduce some of your self-employment taxes by paying out profits in the form of distributions after paying reasonable compensation. This can save you significant amounts, depending on your particular circumstances, but you should discuss this carefully with your tax advisor because there are limits to the effectiveness of this strategy.

S corporations have restrictions on ownership that most LLCs do not have. Some of these differences include:

- LLCs can have an unlimited number of owners whereas S corporations can have no more than 100 owners.

- S corporations can have only one class of stock. LLCs, depending on the tax treatment, can have unlimited classes of stock or ownership interests.

- Non-U.S. residents can be owners of LLCs, whereas S corporations may not have non-U.S. residents as owners.

- S corporations cannot be owned by C corporations, other S corporations, LLCs, partnerships, or many trusts. LLCs are not subject to these same restrictions.

LLCs are not subject to the same formalities as a corporation, but it is very important for an LLC to have a proper operating agreement, especially in the financial services industry, where there are often additional rules for ownership. S corporations face more extensive internal formalities, including adopting bylaws, issuing stock, holding initial and then annual meetings of directors and shareholders, and keeping the minutes of these meetings with the corporate records. These formalities are requirements that exist even for one-person corporations.

In an S corporation, what you see is what you get. It is rigidly structured, it is predictable, and it is inflexible. Some owners consider those points to be detrimental, whereas others consider them advantages. Remember that in most succession plans, there is a distinct possibility that you’ll be a majority owner and a minority owner at different points in time, depending on whether you’re the founder gradually selling your ownership or a next-generation advisor gradually acquiring ownership. Having profit distributions set as a matter of law can be a positive feature, depending on which side of the fence you’re on. In that way, S corporations have the advantage of being investor friendly. Twenty- and 30-year-olds who have never owned a business intuitively understand how stock ownership works and how it is taxed; LLCs, especially when set up as a partnership, are an entirely different matter.

LLCs taxed as a partnership offer a unique strategic advantage in this industry and in the context of building enduring businesses, however. Independent advisors tend towards building their own books, often right under their employer’s roof. In the process we call onboarding, acquiring those books in exchange for an ownership position can be difficult and expensive through an S corporation, in terms of the taxes. Purchasing or acquiring an existing book in exchange for an ownership position (i.e., buying the book with stock of the corporation) results in ordinary income tax treatment to the owner/contributor of that book; the stock he or she receives is taxed at ordinary income rates, often as part of a cashless transaction. In this area, LLCs can have a distinct advantage because of how partnership tax law works.

So, LLC or S corporation? The answer is, for most advisors, both! And now that we have you thoroughly confused, let’s clear away the clutter and get back to that bottom line. While about 45 percent of today’s independent advisors who have an entity structure have chosen the LLC format, two-thirds of all advisors who have an entity are taxed as S corporations, half of them directly, half of them through an LLC tax election. The S corporation is the predominant tax structure to plan around in the independent financial services industry because it works and it is easy to understand and cash flow model.

If you’re already an S corporation, you’ll likely always be an S corporation; you don’t need to change a thing in most cases. If you choose the LLC model, or have already chosen it, you have the ability to elect to be treated like a sole proprietorship, a partnership, a C corporation, or an S corporation, in sequence as your business grows—the best of all worlds. This goes to our earlier point of learning to think two-dimensionally in your entity plans: You file as one thing, and get taxed as something else. Most advisors who set up as an LLC will progress in tax treatment, one step at a time, from a disregarded entity to a partnership to an S corporation. Consider that assumption in your succession planning process; your next-generation owners will.

One last point: LLCs are far more complicated than S corporations, and not by just a little bit. That makes them more expensive to set up and to operate, and it means you’re going to need professional help to do it. Don’t even think of trying to set up an industry-specific LLC, designed to perpetuate a business beyond your lifetime, in this highly regulated industry using some online service or an attorney who doesn’t know what FINRA stands for, or how an RIA handles cash flows. Building an enduring business in this industry is an exacting process. Do it right the first time, and build your business on a solid foundation with the right tools.

Remodeling Your Cash Flow

In order to build an enduring business—something that can outlive you while providing a lifetime of benefits and income through your succession plan—an independently owned practice needs to be repowered with next-generation talent. In fact, as the value, cash flow, and complexity of the business grows, most succession plans involve not just one next-generation advisor, but a succession team with owners filling specific roles in the enterprise. As a founder, don’t be afraid of this change. Embrace it, because it cannot unfold and it cannot be successful without your help; you’re the cornerstone and will be for a long time to come.

To assemble this team, the founding owner has to be able to draw younger, talented advisors into the ownership circle and help them answer a couple of important questions: (1) “What am I investing in, and why?” and (2) “Where does the money come from to enable me to buy into the business and, one day, to buy out the founder or senior partners?” Proper cash flow modeling is the key to helping next-generation advisors invest their money and careers in the business in which they work, because it helps to create a bottom line or profit distribution in an LLC or an S corporation. Profit distributions, actual profit distribution checks issued several times a year to all owners, serve as the practical answers to those questions. Creating those distributions is one of the key steps in transforming your practice into a durable business.

In this book, we’ll assume that all current and prospective owners are actively involved in the business, and are properly licensed or registered to provide services or sell products that generate revenue and help the business pay its bills and grow. In other words, succession planning in this industry tends to be about active ownership, not passive ownership. With these basic assumptions in place, the following is an explanation of how to create a bottom line or profits that attract and reward active, next-generation advisors.

Let’s start with how cash flows through an independent advisor’s S corporation (or an LLC taxed as an S corporation). Basically, there are two ways to get money out of an independent practice or business—wages and profit distributions. But there are three ways to build wealth from the same model: (1) wages (S corporations or LLCs taxed as an S corporation can and should pay W-2 wages to their shareholders), which include bonuses; (2) profit distributions; and (3) equity value.

The addition of equity or business value to the equation is essential and part of the business-building process, because the growth of equity has the lowest tax rate of the three wealth-building tools, and we’re not talking about long-term capital gains rates. Think instead about the tax on the growth of equity in your business or, for comparative purposes, your home; you don’t pay taxes on the growth of equity until the equity is realized. As a growth tool, as a building tool, equity is what separates an independent business from a wirehouse model. It bears repeating: If your broker-dealer or custodian’s practice management team cannot help you address the equity component, then they’re treating you like a practice and not a business. They’re thinking small; are you?

Referencing Figure 3.7, consider the process step-by-step from an owner’s perspective.

Figure 3.7 Cash Flow Modeling

Step One: Collecting the Revenue

A properly constructed and valuable business relies on a strong, centralized entity structure that pays out competitive-level compensation (wages and benefits) for work performed. First, it must collect ALL incoming revenue from everyone who works under the same roof, and deposit every last cent of that money into the corporate (or LLC) bank account. This is a normal function in a fee-only, RIA model where a client can contract directly with the advisory firm; in a FINRA model, this can be a more challenging aspect as the money paid to the individual advisors must be assigned into the entity.

The point is, if revenue is siphoned off through a revenue-sharing arrangement or a commission split, it does not count toward the value of the business. That is the difference between cash flow and equity. That is also the difference between separate books and a single business with enterprise strength. All revenue belongs to a business, without exception, and is distributed as set forth in the next two steps.

Step Two: Paying Competitive Wages for Work Performed

Competitive wages at the ownership level are determined by relying on two information sources: (1) the producer/advisor’s trailing 12 months compensation level and (2) operational benchmarks for practices or businesses of similar size and composition. As a general rule, however, no succession plan or business plan should start with a pay cut to a next-generation advisor who is about to become a new owner as part of the creation of an internal ownership track. Accordingly, determine what the competitive wage is for a particular role in a particular geographical area, but regardless, don’t reduce take-home pay. Making the leap from a revenue-sharing arrangement to a salary and bonus structure is hard, but you don’t have to do it all at once; we often include a tapering element in the planning process (as pertains to the compensation element) as you transform from a practice into a business.

Once salaries are determined, lock in the most recent level of compensation, and don’t change it for the next couple of years—and that statement applies to all owners, including and especially the founder. (Most of the larger businesses and firms we work with do not reset or increase compensation every year—that is the function of profit distributions.) This creates a base-level compensation for the ownership team (check with your CPA to ensure that reasonable compensation levels are paid for tax law purposes if you’re an S corporation or an LLC taxed as an S corporation). Over time, as the founding owner begins to reduce time spent in the office (the purpose of establishing the workweek trajectory), his or her wages tend to remain flat even as the business grows, a benefit of ownership and being the founder.

Alternatively, on occasion and depending on the circumstances and the planning parameters, the founder’s wages can gradually be reduced as the founding owner works less, but only as he or she receives incoming payments from the succession team who are gradually purchasing their equity at increasing stock values—taking into account that these monies are received at long-term capital gains rates by the founder/seller. Connect the dots: As wages decrease or level off and as the business grows, profits will increase, triggering a faster buyout of equity from the founder at preferential tax rates—all excellent reasons why you should plan first, and thoroughly, before implementing your succession plan. There are a lot of moving parts.

As a result of this cash flow remodeling, the role of variable-level compensation is shifted to profit distributions—an element to be reserved for those who actually invest their money and careers into the building of a single, enduring business. It is essential that the founder pays at least competitive wages in order to attract and retain exceptional talent for the long term, but it is a mistake to overpay by a significant amount (which almost always occurs when you use a revenue-sharing arrangement or any form of an eat-what-you-kill system), thereby making an investment in ownership unnecessary by the employee or producer/advisor. Why invest and take a risk when a share of the profits automatically comes with the paycheck?

Step Two and a Half: Bonuses

The immediate push-back in a sales-based organization is that a pure base salary coupled with profit distributions does not properly incentivize employees to achieve the results needed to grow the company. If that is the case and you believe the company goals cannot be met without production-based compensation, then we suggest using bonus structures specifically targeted to the behavior that the practice is trying to encourage rather than simply tied to a blanket revenue goal or production from an individual. Using a bonus incentive tied to bringing on new clients or to increasing so-called share of wallet is better than using revenue-based splits or commissions, which often reward advisor employees for simply participating in a good market rather than achieving the goal of building value. By using appropriate base compensation combined with profits to the owners, bonuses gradually become a smaller component of an advisor’s compensation package and one that serves more to focus on the right objectives while keeping things interesting and competitive among your junior advisors.

Step Three: Profit Distributions × 3

A flat, or at least a more flat, wage level means that after operational expenses are paid and a suitable reserve is on hand, all remaining monies as well as all future revenue growth (after expenses) will be channeled out of the pass-through entity structure as profit distributions to the advisor/owners. Remember, in an S corporation tax structure, profits flow to owners in direct proportion to ownership (i.e., a 15 percent owner receives 15 percent of the profits). Profits serve three distinct functions: (1) serving as a return on investment, (2) serving as the variable component of take-home pay (a very different and effective approach when compared to revenue-sharing arrangements), and (3) providing the means of paying for the equity being acquired from the founder. Again, those are the critical differences between a practice and a business; creating a bottom line is how you create and sustain an enduring and valuable business.

Flattening the founder’s W-2 wages also means that the founder can’t take out all the growing profits as a bonus to himself or herself. Instead, by paying those monies out as profits, an important business-building function is attained: advisor/owners learn to think like owners, focusing not only on production (which is still job number one), but on profitability as well. This structure reflects the philosophy that owners of small but growing businesses are not motivated only by a paycheck, but by the increasing size and share of their profit distributions, and by the growth in value of their investment (think shareholder value), or equity—three ways to build wealth as a business owner.

Obviously, in order for advisors to increase their share of the profits and to increase the amount of their variable compensation in terms of actual dollars, additional ownership must be purchased, and that is exactly the mentality needed to create and sustain the succession team. But there are two additional and easier ways that next-generation owners can increase their take-home pay as equity partners. One is to grow the top line—help make the business grow and take more and more of that responsibility on as a member of the succession team. The second is to watch the bottom line: How profitable is this business? How does it compare with other businesses of similar size and structure? What expenses can be cut without affecting growth?

Simply asking the questions is a step in the right direction for the next-generation team of owners—the succession team. But you have to get them to focus on production and profitability simultaneously; that is what owners learn to do. And owners learn very quickly, because production and profitability immediately and directly impact their take-home pay. The greatest failing of a revenue-sharing or eat-what-you-kill arrangement is that those compensation methods make the bottom line completely irrelevant to all but the founder, who alone, late at night, worries about the increasing overhead.

Step Four: The Investment in Equity

Building a practice requires a focus on production. Building a business requires past and future leadership to make the connection between a growing cash flow stream (production) and the costs of such growth (profitability); it shifts the focus to the bottom line. Having and distributing profits, a bottom line, attracts next-generation advisor/owners who can, in turn, provide continuity and longevity. At this point, it bears repeating: Structure your business and its organizational, entity, and compensation systems so that there is no way for an individual to do well unless the organization succeeds as a whole.

In general, here is a good formula to consider as a goal for the business you’re building: About 35 percent of all incoming revenue should be allocated toward overhead (business expenses, not including ownership-level compensation); about 35 percent of all incoming revenue should be allocated to ownership level and advisors’/producers’ compensation; and about 30 percent of all incoming revenue should find its way to the bottom line, to be allocated to profit distributions and accessible only by those who have invested in the firm and are shareholders or legal owners. We call these “performance ratios.” Many owners don’t or can’t start with these performance ratios, but understand that taking control of the “wage line” for all owners, advisors, and producers through a salary and bonus structure means that, in time, with sustained growth, things will change, and improve. All you have to do is plan thoroughly, and take the first step.

Stop the revenue-sharing and/or commission-splitting arrangements and you can grow your way through many of these challenges as you evolve from a practice to a business of enduring value. When 30 percent of your revenues become accessible only to those who actually invest their money and their careers in your business, a funny thing will happen: People will start to value ownership and equity. They will want to become equity partners, building on top of what you’ve built.

Production Model versus Business Model

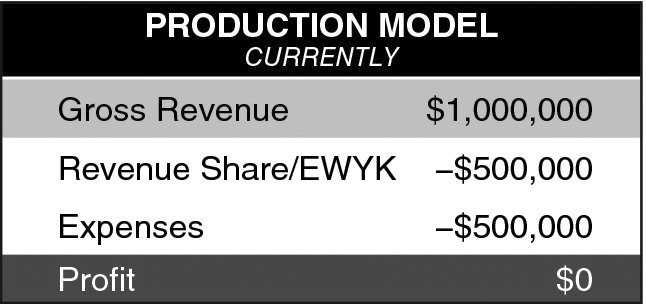

So, if building a business with a bottom line makes it more sustainable and more valuable and sets up a strong succession plan, why don’t more owners employ this method? The answer lies in the fact that most practice owners tend to focus their efforts almost entirely on production without thinking about the trade-off in terms of equity and enterprise strength. In this section, we compare the production model and the business model works, side-by-side, and show you the math.

A typical arrangement is illustrated in Figure 3.8; assume a fee-based practice with annual gross revenue of $1 million. The producers in this model, including the owner/founder, are paid on a 50 percent revenue-sharing arrangement; in other words, everyone receives 50 percent of every dollar of revenue they produce. After paying the overhead (staff compensation, lease costs, benefits, utilities, marketing, technology, management, etc.), there is little or no meaningful profit.

Figure 3.8 Typical Production Model

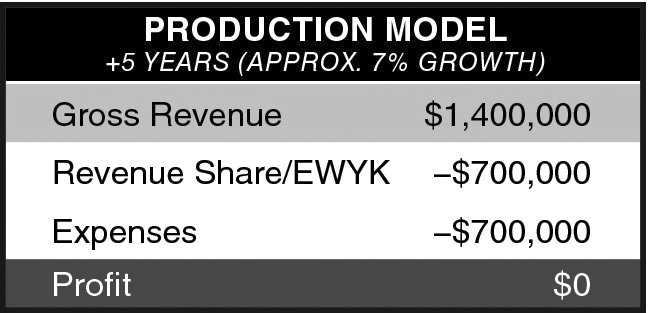

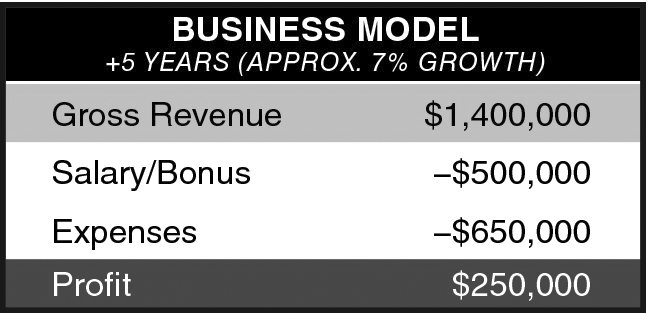

Most independent practices and businesses operate as pass-through tax conduits (sole proprietorships, S corporations, and LLCs taxed as a disregarded entity, partnership, or S corporation), so actual owners may not consider lack of profits an issue. If the goal is simply to generate a good living and to have maximum individual control over the engine of production, there is nothing wrong with this approach. But consider what this same model looks like five years later (Figure 3.9) when there is little or no meaningful profit compared to the business model in Figure 3.10.

Figure 3.9 Creating a Bottom Line: Current Production Model

Figure 3.10 Creating a Bottom Line: Business Model in Five Years

Assuming a 7 percent annual top-line growth rate for the five-year period, the production model has grown at the same rate as the business model. Both have the same top-line revenue, and both owners make about the same amount of money. So what’s the difference? Equity. The business model is worth in the neighborhood of $3 million; the production model is unsalable as a business because the nonowners control their own books and it is highly unlikely that all producers will sell in unison. In fairness, the production model is built for producer enrichment, not owner’s equity—but with the business model, you have the same production and the advantage of equity value.

In the business model, the function of controlling and gradually flattening the compensation line with a salary/bonus structure, as we illustrated in the preceding section, results in a bottom line. The profits, in turn, are reserved for those who legally own and who financially invest in the business—advisors who buy stock from the founder. Because the business model now has two or more owners who focus on the bottom line (and for good reason since it impacts their take-home pay), expenses tend to be better controlled as well. The margin between revenue growth and expense growth tends to improve, and that further improves the bottom line over time.

The profits generated in the business model are distributed approximately quarterly to the owners in the business. If minority owners want to increase their profit distributions, they will have to think like an owner: (1) grow the top-line revenue (production is still job number one), (2) reduce overhead costs, and/or (3) buy more stock. All of a sudden, the implicit value of ownership has increased without lessening the business’s rate of growth. Granted, the compensation systems we examine a thousand times a year are more varied and a little more elaborate than we’re illustrating here, but the common denominators in almost every case are some type of EWYK system and a one-owner practice model focused almost exclusively on production.

In sum, remodeling your cash flows means that things are going to be different. You will have to learn to use your financial data more effectively, and that function will make you a better owner and advisor, especially to your business clients. Once these systems and processes are in place, however, most owners find that the cash flow structure is not more complicated—it is more sophisticated. It will increase business formalities, which is to be expected as a business becomes investor-worthy. From the founder’s perspective, flexibility (in terms of his/her personal salary and distributions) is gradually exchanged for predictability and reliability, even longevity.