Chapter 2

How to Start Creating Your Succession Plan

When considering your succession plan, your actual starting point depends on what you want or need your business to do for you, your family, your staff, and your clients. Remember that the goal of most succession plans is not to remove you as the founder and put you out to pasture; the goal is to build an enduring business around you that can provide an income stream for life while providing leadership and mentorship to a team of internal successors while gradually handing off the reins over a period of 5, 10, 15, or even 20 years if the planning process starts early enough.

Defining Your Goals

There is a high degree of customization for every succession planning strategy. In fact, over the past 16 years, we’ve never done any two plans that were exactly the same. Plans are kind of like a set of blueprints for your dream home. While the building materials and assembly techniques for most homes are very similar and the tools consist largely of hammers, saws, drills, and the like, every home is as unique as the person(s) it is constructed for. That’s how it is with designing and developing a succession plan—it is a plan that starts with you, and your goals and dreams.

The problem with setting specific goals for a succession plan is that you’ve probably never done this before. You’ve walked through other people’s homes and gotten some great ideas while figuring out what you like and don’t like, but most advisors never get to see another advisor’s actual succession plan. It is very difficult to decide what you’d like to do if you don’t understand what is possible, what is normal, and what won’t work—these are all tasks that this book will help you with. In fact, we’ll actually show you pictures of various plans, what we call “succession planning schematics” or blueprints.

Many advisors have an idea of what they’d like from a succession plan, such as creating a legacy, cashing out, spending less time in the office, and/or maintaining current cash flow for as long as possible—all valid starting places and ideas to build on. Some advisors think of their buy-sell agreements (that are triggered on death or disability of the owner) as their succession plans. This approach can transfer assets and relationships, but having to die to implement any kind of a plan maybe shouldn’t be your first choice! We can do better than that.

So, while your plan will almost certainly contain a number of very personal goals, here are a few of the more common and general succession planning goals we hear on a weekly basis, beginning with the most popular:

- Develop a strategic growth plan that doesn’t center on the founder’s skills.

- Create a practical and reliable continuity plan that will protect the value and cash flows of the practice.

- Provide for income perpetuation to the founder for his or her lifetime.

- Transfer the business to a son, daughter, or other family member in a tax-efficient manner.

- Accommodate an on-the-job retirement while never fully leaving the business.

- Work for another couple of years and then sell and walk away or fade away.

- Merge with another business as a means of growing, protecting, and optimizing value.

All these goals can be accomplished under the right circumstances, but some do require more time than others. While selling to a third party doesn’t take a lot of advanced planning, for example, selling internally does. Executing an internal ownership strategy can easily take 10 years or more. Perhaps the best question to ask isn’t “When is it time to start?” but “When is it too late to accomplish your goals?” In this chapter, we’re going to help you answer those questions and more.

Rethinking Your End-Game Strategy

Conventional wisdom suggests that an independent financial professional should choose, at some point in his or her career, between an internal succession plan and an external sale to a third party or a merger with a third party (as in a peer, a competitor, a bank, or a CPA firm). That’s wrong. Forget it.

The smart plan includes both options right out of the gate, but always starts with the internal ownership transition strategy—even if you have only two people, including yourself. The task is to design and develop a plan to guide your journey. If your internal plan doesn’t work out to your satisfaction (and that is always a possibility), an external sale to a third party becomes your fallback strategy.

As you’re now aware, more than 90 percent of advisors will never sell their practices—at least not in the conventional sense—because the value they covet is not that offered or paid for by an outside, third-party buyer; the value most advisors are after is cash flow, the money they take home every year from work that is rewarding, as well as a client base that is more appreciative than not. Advisors would simply rather keep working, and keep earning the income that supports their lifestyle; the truth is, most advisors need to keep working because their lifestyles demand it. And even if they didn’t, the stream of income multiplied by “five more years of working” is a more powerful incentive than selling for a lump sum and living off those proceeds.

So make selling your practice plan B, and face the music—there is less than a one-in-10 chance this is going to happen. You’re not helpless in this matter, of course; plan B is mostly within your control unless and until it is triggered by death or disability (the purpose of a continuity plan) or you choose the attrition route and there is nothing left when you’re done with it. Later in this book we’ll help you better prepare for these possibilities. In the meantime, let’s shift to plan A and start to figure out what that might look like for you and your stakeholders.

Setting up an internal ownership track (which is what powers a succession plan) provides for a stronger and more stable business, which in turn provides higher value in the future regardless of your exit strategy. It can also provide excellent protection against the founder’s short-term or temporary disability. Attracting, retaining, and properly rewarding next-generation talent is an essential step in moving beyond a typical practice to a more valuable business model and solving these problems.

As a business owner with a succession plan in place, you can lead and continue to participate in the business you’ve founded for decades to come if you build an enduring and transferable foundation. In addition, the effective value received can be upwards of six times the trailing 12 months gross revenue, based on the starting point for the plan (including equity and profit distributions)—a fair return on your investment of time and leadership. The final, effective value derived by selling equity incrementally in a growing business is significantly higher than a sale to a third party, but only if you build the foundation to support this process—something to consider as you formulate your goals. Do you want to do this? Are you up for it? It is okay if the answer is “Maybe not,” because honest answers provide for better goal setting and more accurate planning. Just understand that most plans can be designed around your preferences if there are sufficient time and resources.

We ask every one of our planning clients what “retirement” means to them. The answers are mostly the same. Retirement for an entrepreneur rarely means a hard stop; usually it is a gradual, on-the-job retirement from five or six days a week down to four days, down to three days, and so on. But that works only if there is next-generation talent to back you up, and a plan to tie it all together; otherwise, it is called attrition and any value other than cash flow will evaporate by the time most advisors call it a day. Worse, if a health condition or an accident cuts your plan short but doesn’t kill you, the cash flow is gone, too, even when you need it most, and there probably won’t be any funding to cover the equity value.

In the end, it all comes down to what you want and need from your business, and how much time there is to build the foundations and to implement and adjust the plan. That’s why figuring out when to start is so important.

Determining a Precise Starting Point

Most advisors who do embark on designing and implementing a succession plan are starting about 10 years too late. Every year, we work with several hundred advisors to set up formal, long-term succession plans, and these founding owners tend to be around age 60 when they start the planning process—not too late for a successful plan to be designed and implemented, but not optimum in terms of maximizing results and having the broadest array of options.

So when should you start developing your succession plan? The short answer is, start the succession planning process by age 50, plus or minus five years. The longer answer is that it depends on what you want your business to do for you in the future. For the one advisor in 10 who actually will sell and walk away, start the planning process about three to five years before you think you’re ready to pull the plug, and monitor your equity value annually to make sure you’re not already in attrition mode and bleeding off value before you sell; at some point, practices do become unsalable.

One of the best ways to determine when to start your succession planning process is to first plan your “workweek trajectory.” In other words, instead of focusing on either how much money you need from the business, who might possibly comprise your succession team of next-generation talent, or how much ownership you’re willing to part with during the initial stages of your plan, look instead to something much simpler and closer to home—forecast the amount of time you would like to physically spend in the business in the years to come. We use a graph like that in Figure 2.1 to determine an advisor’s current workweek trajectory and goals for the future.

Figure 2.1 Workweek Trajectory

Start the trajectory with an accurate assessment of the average number of hours you now spend in the office or working diligently on office-related matters from home. Then plot how many hours you’d like to be working in five years, 10 years, and so on. What is your goal and what would you like your business to do for you? Just to provide you with a level of comfort before we proceed, we tend to assume that perpetuating your current income level is a part of the succession planning process, even as you slow down and reduce hours in the office, so this important consideration isn’t being ignored. We plan for it every time.

Some workweek trajectories bottom out in future years, which signifies a hard stop at some point in a career, and an end to at least the income stream for the founder, but most don’t. Most advisors plot a gradually descending workweek plan but level it out at about half time based on what they’re used to as full time. One of the benefits from a well-structured succession plan is the ability to elongate your career by reducing the hours and the stress, and by shifting the things you don’t like to do to your up-and-coming succession team. Extending the length of your plan means a longer period of income and profit distributions along the way—in other words, a more lucrative retirement whenever and however that event might unfold, by working less. But to make that all happen, you need a good plan.

You’ll notice that there is a horizontal dashed line drawn at the 30 hours per week level. We call this the “30-hour threshold.” The 30-hour threshold provides an important lesson for founders and succession planners: There are more ways to shift control, or to lose control, of a small business than just selling shares of stock in your corporation, or membership interests in your limited liability company (LLC). Independently owned financial services or advisory practices are notoriously intolerant of absentee ownership, especially when the compensation systems in place are revenue-sharing arrangements or any form of an eat-what-you-kill system.

Working less and less as you get older makes sense and to some extent is inevitable; in fact, plan on that happening. But at a certain point, about 30 hours per week on average over the course of several years, attrition will begin to take its toll. Here is what happens.

Over time, the equity value of your business, specifically the value of your ownership and shares of stock, can be reduced to the value of the assets, namely the client relationships. As you work fewer and fewer hours but remain the owner of 100 percent of a practice, especially one with a revenue-sharing or other eat-what-you-kill compensation structure, the very portable assets of the business can factually transfer to the advisor who regularly sits in front of the clients and helps them. The result is that, at some point, the assets and client relationships take on more value than the founder’s stock (or ownership interests in an LLC), and the next-generation advisors suddenly have something to negotiate with—something powerful and valuable that they control without having to purchase anything. In other words, the clients will follow the junior advisor across the street if he or she elects to go that way.

Accordingly, you should start your formal succession planning process five to 10 years before you break the 30-hour threshold. If you do, there is no reason why you can’t enjoy the lifestyle the business provides, perhaps for the rest of your life, along with the cash flow and the gratitude of your clients and your family.

Building a Foundation for Success

In fairness, almost every small business has to start out with a singular focus on revenue—you have to make money to survive and make it to the next year. The art of production, learning how to give great advice and/or sell appropriate products and services, is how advisors make a living, and for that reason “revenue strength” is the principal component in determining the value of a privately held, independent financial services practice. Building revenue strength is almost intuitive to advisors, but rarely is it balanced by “enterprise strength” (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Balancing Revenue Strength and Enterprise Strength

The basic goal of every succession plan we design and implement is to build an enduring and transferable business. Making the leap from a one-generational practice to an enduring business is not actually the role of succession planning; a succession plan builds on top of a durable business foundation and creates a plan for the transition of ownership and leadership. Building the foundation should be an entirely different process, one that needs to start closer to age 40 for the founder if it is to achieve maximum success with a staff in place and trained to support the business; ideally, with time and information, the process will begin upon day one of the business.

Most of the succession plans we design and build, however, require that we first retrofit the practice with the foundation and structures needed to build upon to create an enduring business model. So, if you are reading this book and you are under age 50, forget succession planning for a moment (yes, those are brave words in a book about succession planning!), and focus instead on building the foundation of a business that can provide you with a great succession plan when the time comes, such as when you’re over age 50! It will happen, trust me. In the meantime, your energy is better spent building the foundation of a business that is valuable, uses the correct compensation system, and is set up to attract and retain contributors to your business who can eventually be included in your succession plan.

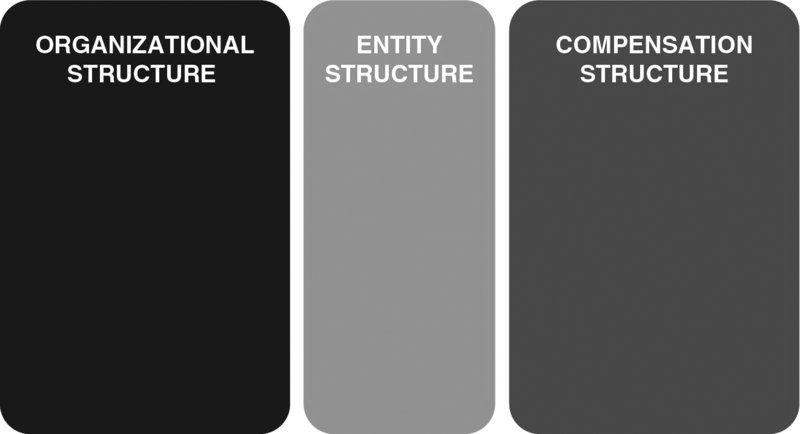

If we could boil this section down to one sentence, here it is: Structure your business and its organizational, entity, and compensation systems so that there is no way for an individual to do well unless the organization succeeds as a whole. There you have it: the secret of building an enduring business model. But how do you do that?

There are three areas that you will have to address and improve upon, some immediately and some more gradually over the coming years:

- Your organizational structure

- Your entity structure

- Your compensation structure

Understand that there is a fair amount of overlap between these areas, as will be evident from the instructions and explanations provided here. This overlap functions more like reinforcement rather than redundancy, adding strength to your business and its sustainability over time; but it also creates the possibility of weakness if you do just one or two of these right and fall flat on the third. You have to do all of them with at least a modicum of success, and this book will provide a lot more information on each in the pages that follow.

Advisors, like business owners everywhere, have a lot on their plates. It is easy to get overwhelmed when you look around and think of all the things you have to do and try to figure out where the time and energy will come from. Instead of looking around your office as it sits today, think about it this way instead: Imagine your business at twice its current revenue or value—what will the company be doing differently? What will your role be in that organization? What people will you need to add to get the business to that level and to take some of the load off you? If you’re not retiring in the next 10 years, plan around such a goal and think long term as you hire and build—but plan before you hire and build.

Facing Your Biggest Challenges

My first foray into the world of the independent financial services professional occurred more than two decades ago as a securities regulator. While employed by the Oregon Securities Division, I discovered and investigated one of the largest financial fraud cases in the state’s history. But on my first day at work I was handed a copy of the Oregon Revised Statutes (ORS) and the Oregon Administrative Rules and told to write up a set of proposed rules for transitioning an independent practice. The Internet was still a thing of the future, so I learned the old-fashioned way: I picked up a copy of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, ORS Chapter 59 on securities regulation, and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, and I read the material, page by page; then I started asking questions.

Of my more experienced colleagues, I asked: “Can independent advisors sell their practices when they’re ready to retire?” and the answer was: “Of course not; there is nothing to sell.” I then asked, “So what is the point of writing up rules for transitioning their client base?” The answer was in the ballpark of: “Just follow the rules the wirehouses use—that’s how everyone does it. There is no discernible difference between the two models.” And that answer has stuck with me ever since—just do what the wirehouses do. Of course, that answer and its logic were wrong, but it permeates the culture of advisors to this day.

We have the opportunity to talk to thousands of independent owners and their staff members every year, and almost everyone still has some tie back to the wirehouse side of this industry. Some of you started your careers there and learned the ropes before jumping to the independent side. Others learned from a boss, a parent, or other mentors who received their training from one of the large, captive models. The wirehouse industry provides the foundation and education for most of today’s independent financial professionals and advisors. To be sure, there were many, many good lessons to be learned and brought over to the independent space—but there were also some lessons and tools that simply do not apply to those who own their own business.

Over the past 20 years or so, independent ownership is the story in the financial services industry. But independence has an Achilles’ heel—the practices die off with no one to succeed the founder. Too many practices aren’t even capable of generating a successor because of how they are assembled. The culprit is the use of wirehouse, employee-based compensation and reward systems that make production and sales achievements the pinnacle of a career. Not to say for a minute that these venerable institutions don’t do a lot of great things for their clients and this industry, but there is simply no need for these folks to learn how to build an enduring and transferable business—that is not a necessary task under the wirehouse model.

In the independent space, building a business would seem to be the pinnacle of most careers, and it will be just as soon as independent professionals discover the most powerful and lucrative tool they have: equity. Equity is the value of the business separate and apart from the cash flow and compensation paid for work performed. It isn’t that equity is struggling to get a foothold (it’s not), but in this young industry, 70 percent of the professionals make less than $200,000 a year, and the immediate value they care about is cash flow; with little or no infrastructure, nothing they do even remotely looks or feels like any kind of business, and it isn’t.

The problem, however, isn’t limited to small practices or new start-ups. The independent professionals and advisors we work with that have annual production or gross revenues of greater than $5 million, even $10 million, almost all use some form of revenue-sharing arrangements or an eat-what-you-kill system that rewards sales and production tied to the top line, not the bottom line. “Fracture lines” are built into the practice model as individual books or practices are built in an environment that starts out collaboratively but most often ends up creating competitors. And advisors do this over and over again as if it were the most normal and natural thing in the world—which it is on the captive side, but Dorothy, you’re not in Kansas anymore.

It is time to dispense with obsolete practices and incorrect building tools and to recognize that the world of the independent advisor is different from being in a wirehouse. Building an enduring and valuable business should be the goal of every independent professional with annual production or gross revenues of $500,000 or more. It is time to stop “owning a job” and get to work, building efficiently and effectively with the proper tools and for generations to come. Some of the biggest challenges you’ll face in doing so lie in discarding what you’ve been taught is normal and right.

The Persistence of a Job Mentality

Correctly structuring compensation at the ownership level is a critical element to building a valuable and enduring business. Ownership-level compensation cannot be determined by a chart or a survey or even benchmarking data; at this level, the common mistake is to focus on the question of how much an owner should be paid, instead of how an owner should be paid. Independent advisors start this part of the planning process by seeking answers to the wrong question.

The compensation system most commonly utilized by independent financial professionals in this industry is some form of a revenue-sharing or commission-splitting arrangement. Revenue sharing is an easy and seemingly low-risk payment system to implement—certainly, on the surface, easier than hiring a bookkeeper and setting up a payroll service to generate a W-2 wage and withholding system. But the risk and true cost of a revenue-sharing arrangement become increasingly apparent the more successful the younger advisor becomes; any value other than the share of revenue typically belongs to the individual advisor responsible for building the book.

Instead of building businesses that evolve and improve from one generation to the next, advisors in this industry build one-generational practices, and subsequently rebuild them from scratch with each new generation of owners largely because of these eat-what-you-kill compensation systems. For that reason, jobs and practices that last for just one generation of ownership are plentiful; multigenerational businesses and firms are rare. The goal of a practice owner is one of production, and production equates more directly with cash flow than it does with equity.

In the independent sector, if your goal is to build a valuable and enduring business, then your focus should be on a team of advisors working together, compensated for contributing to and supporting a single enterprise, rather than building individual books and subsequently leaving with the clients and related cash flow they generate when the time is right.

Revenue Sharing: Heads They Win, Tails You Lose

Let’s examine this premise. You hire a 32-year-old advisor (we’ll call him Bob) with a newly minted certified financial planner (CFP) designation and a small book that may or may not follow him, but he is fully licensed (or registered as an IAR) and ready to go. You agree to a small base salary for one year, credited toward the payout structure, which is a 50/50 revenue-sharing arrangement. Bob turns out to be a complete and total failure. He couldn’t sell a space heater to an Eskimo or create a financial plan that looks out past the end of the week. You let him go. You saved the costs and complexities of setting up a payroll, and you didn’t pay for what you didn’t get; but did you win? What exactly did you gain in this arrangement?

The best argument is that you cut your losses and on that point we’ll concede. You definitely did that. But you lost a year or more in the effort, you’re a little older and thinking about slowing down yourself, and now you have to start over with a new hire. So let’s rewrite history and explore this from a different angle.

Bob instead turns out to be one of the best professionals you could have hoped for. He comes in early, he stays late, your clients love him, and most of his clients followed him. He produces $250,000 in gross revenue (or gross dealer concession [GDC] under Financial Industry Regulatory Authority [FINRA] rules) by the end of his second year, and all indications are that he’ll double that by the time he has five years in with you. What exactly have you gained in this scenario?

Well, you get 50 percent of everything Bob produces, so that’s $125,000 a year by the end of year two. That’s a good thing. Bob takes the same amount of money home as his reward, a good payday for him as well. Of course, Bob hasn’t had to spend any money on desks or chairs, a computer or a customer relationship management (CRM) system, a phone system, the office space, or a computer network or the staff to make all these aspects of a business come to life, but you did. So you take your half and you pay the rent, the staff, the light bill, and other expenses, and then you take home what’s left. You own half the cash flow, halved again after expenses, but what about the equity—the value of the book?

After year five, Bob does indeed reach his goal and now produces almost $500,000 in top-line revenue per year. About 70 percent of this revenue is recurring. You decide to make Bob a partner in your business and offer him the opportunity to buy in, but Bob astutely asks, “What about my book? Do you want to buy what I’ve built or exchange it for an equivalent amount of stock?” Those are really good questions, and we hear them almost every day. You own part of the cash flow, while Bob owns all the equity. Bob controls the assets, and those assets (the client relationships) are portable. They may not all follow Bob as he walks across the street and hangs out his own shingle, but they could, and therein lies the strength of Bob’s negotiating position.

This example illustrates the concept that, as independent advisors, there are two kinds of value: cash flow and equity. This is a critical distinction that separates an independent practice from a captive or wirehouse practice.

The point is that setting up a revenue-sharing arrangement or any form of an eat-what-you-kill payment structure is a losing proposition for the founder or actual owner, unless you own your own independent broker-dealer or custodian, a wirehouse, or an office of supervisory jurisdiction (OSJ); don’t emulate these models for any other reason. Remember that most of those models are worth far less, per dollar of revenue generated, than your own enterprise. If the next-generation advisor fails, you lose. If the next-generation advisor succeeds, you have to buy what he or she has built and pay for it with the stock or ownership interests of your own business, or risk creating a competitor, and you lose again. Is cash flow alone, after expenses, worth that cost?

Think about this from the eyes of the next generation. When younger advisors are hired into a practice with no future of its own, a practice that is tied to the life or the career of its single owner, the very natural tendency is for them to build their own practices or books. Said differently, if there is no single enterprise to invest in, they start building their own practices and that is exactly what is happening in this industry. Acknowledging that is the first step toward building a business of your own that works for you.

Fracture Lines!

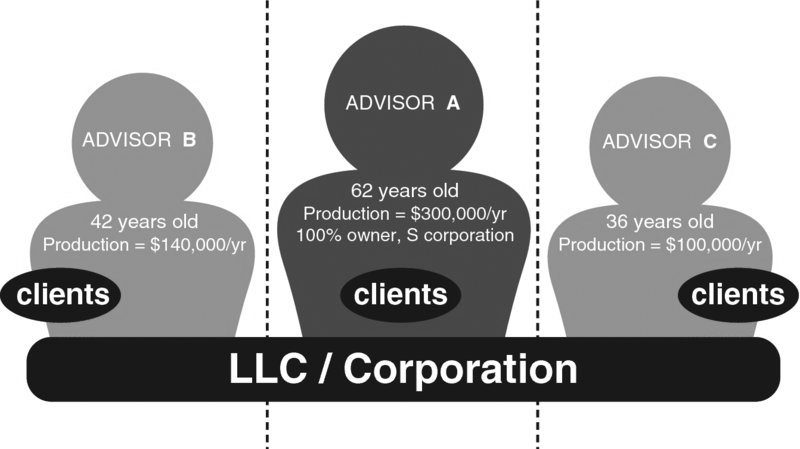

Revenue-sharing arrangements and other eat-what-you-kill compensation structures seriously undermine the effort to build a valuable and enduring business. Practices with more than one producer or advisor are being built with fracture lines from day one. Consider the diagram in Figure 2.3. In this example, Advisor A, who is 62 years old, is the 100 percent owner of an S corporation. He hires and mentors Advisor B, who is 42 years old, and years later, Advisor C, who is 36 years old. Advisor A provides his younger associates the bottom half of his client base and all new client referrals that are below his minimums or who are just not a good personal fit. This fee-based practice has a value of just over $1,000,000.

Figure 2.3 Fracture Lines

Four years later, when Advisor A is nearing retirement and is faced with a sudden and serious health condition, he decides to sell the business and turns to Advisor B. Advisor B is interested in being the buyer, but doesn’t want to pay for his own book, and certainly won’t pay anything for Advisor C’s book. When Advisor A looks outside the firm, a third-party buyer materializes and offers $1.6 million for the practice, but there’s a catch. Advisors B and C must sign noncompete, nonsolicitation, and no service agreements, and/or formal employment agreements with restrictive covenants so that the buyer knows they won’t interfere with or impede the buyer’s ability to control and retain the acquired client base—except that they won’t cooperate. And why would they?

All of a sudden, Advisors B and C’s zero ownership positions are worth something—quite a lot, actually, as the junior advisors now have veto power over the value of their own books, cumulatively about $500,000 to $600,000 in value. The mistake most founders make is that they ask us to value the combined cash flows and think that they own and control 100 percent of the equity. How could they control 100 percent of the equity value when they or their practices don’t control 100 percent of the asset base? This isn’t one business; it is three separate practices. The fracture lines were built in from the first day Advisor A hired each junior advisor and paid him using the industry standard revenue-sharing arrangement.

This common example provides the junior, nonshareholder advisors with control over the assets (the client relationships) even though they haven’t invested anything into building their own businesses: no lease of office space, no phone system or computer network, no employee payroll. All these things are provided through a revenue-sharing arrangement from Advisor A, who was willing to accept cash flow in exchange for the control and value of the assets in each junior advisor’s book. This is not an anomaly; this is why there are so few sustainable businesses in this industry.

The junior advisors, in turn, enjoy cash flow with minimal investment and risk—what we describe as “owning a job.” But what happens if Advisor B or Advisor C gets hit by the proverbial bus as he steps off the curb at the end of a hard day? He owns nothing that is transferable. His family receives little or no value even with the typical revenue-sharing continuity agreement, and, with no infrastructure, the relationships he controls are gone in a heartbeat.

These built-in fracture lines take a single practice with multiple advisors and create multiple books that, cumulatively, are unsalable and therefore end up somewhere between worthless and worth less (than they should be). Creating a competitor is never the goal, but unfortunately creating an equity partner and investor, at least for 99 percent of advisors, hasn’t been one of the goals, either. It’s time to change that, and as an independent owner, you have the perfect tool for the job—equity.

Equity—A Powerful Business-Building Tool

Independent financial services professionals enjoy a distinct and important advantage over captive advisors: They have two kinds of value to work with to reward themselves, to build with, and to use to attract and retain next-generation talent:

- Cash flow

- Equity

Equity is the key—it is what separates a one-generational job or practice from a more valuable and enduring business. Equity has always existed in the independent practice model, but it was more theoretical than practical up until the point where it could be accurately and affordably measured. Once measurable, equity required a proving ground, a place where the measurements could be tested and adjusted against a network of third-party buyers. Would buyers actually pay the values sought by sellers? The short answer was an emphatic “Yes!” Today, there is a 50-to-1 buyer-to-seller ratio, which supports a strong value proposition and a margin of error on FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation Report of plus or minus 4 percent.

Let’s start with the most familiar form of value—cash flow. Independent owners pay themselves from the cash flow generated by the work they do, the products they sell, or the advice and guidance they provide; its flexible, it’s fluid, and it’s fun. Owners know how much money they take home every month. By the end of the year, with help from their bookkeeper and/or CPA, owners know precisely how much money they made, and how (wages, bonuses, draws or distributions, 1099, or W-2). And by comparing income statements, an owner knows how much more (or less) he or she made this year compared to years past, to the penny.

The equity value of a practice or a business or a firm is similar in many respects to the benefits of the cash flow, and different in a few key aspects. Equity exists because of the competitive open marketplace that generates a 50-to-1 buyer-to-seller ratio. It’s kind of like owning a house; if the demand is high, you have value; you don’t have to sell your house to have value, and that is exactly how it is with a financial services or advisory practice or business. Most advisors will never sell, but most have significant value, and that value is a powerful building tool when integrated into a long-range planning strategy, because equity is what next-generation owners actually invest in. (See Figure 2.4.)

Figure 2.4 Business-Building Tools

Just as cash flow has its measurement tools, so too does equity. Equity is determined by a formal and professional valuation (not a multiple of revenue or earnings, which is like measuring the sufficiency of your cash flow by what’s left in your checking account at the end of the month!). Annual valuations, an essential part of the equity management process, provide a library of valuation results, creating a historical record that is of great interest to key staff members, new partners, or recruits being offered a current or future ownership opportunity in the practice.

Equity grows from year to year in most cases, certainly over a span of time if the business is growing. Equity has the ability to provide a regular income stream to the founder or founders of an independent financial services business with proper planning. Cash flow has the advantage of being immediate; in an established practice or a business with recurring revenue, it arrives predictably, and the overhead to generate it is more or less predictable as well. Cash flow is the part of a practice that founders are willing to share. Equity is what next-generation advisors invest in, and buy from an informed founding owner with a solid succession plan. Equity is what provides the return on investment advisors make, and it serves as the means for many of those investments as well.

A frequent mistake made by advisors in the independent financial services industry is to equate cash flow with equity or practice value (or to link the two in a linear fashion with a fixed multiple of something times the trailing 12 months revenue). To this end, doubling the amount of cash flow in an incorrectly but commonly structured practice model often results in little or no change or improvement in the value of the practice. In other words, if value is created and retained by individual advisors, it makes little difference whether you surround yourself with two, three, or 10 advisor/producers—you might make more money in the short term as cash flow, but you will build almost no business value in the long term and there will be nothing for next generation advisors to invest in. And when you stop working, by fate or by design, the cash flow stops, too; and, with no enduring or transferable business value, the practice dies.

Measuring equity and using the value of the business as the primary determinant for growth is important because equity not only is a reflection of the cash flow and revenue generation capacity of a business, it also demands an assessment of the underlying foundation that supports the business’s ability to grow and deliver services over time. Sustained equity growth directly impacts wages, benefits, profit distributions, and the ability of the business to maintain these functions from one generation to the next—a business of enduring and transferable value.

Valuing a Financial Services Practice

What creates value in an independent financial services or advisory practice? At its most basic level, value lies in the client relationships. In the earliest phases of the open market for financial advisors, most if not all of the value rested in the client base and the associated revenue. Even the language of the day referenced this characteristic, referring to the sale of an advisor’s book, rather than the sale of a business. In this context, the supporting structure of services and staff, as well as other licensed professionals, was considered of secondary importance to the cumulative assets under management waiting to be transferred to another caretaker.

Valuation techniques have evolved to the point of being able to assess accurately the cash flow potential of a practice’s client base, as well as the risk elements in transitioning that client base to another advisor or business. But the newest valuation techniques factor in more than just the clients and their revenue, adding infrastructure to the equation, what we call “enterprise strength”—the number of licensed employees who remain through a transition, the nature of the referral channels, and the level of technology in the practice, among other things. In other words, current industry-specific valuation methods consider the business elements as well as the details of the client base to ascertain value.

This approach mirrors exactly what is now happening in the evolving financial services marketplace. Astute and experienced buyers are seeking out advisory practices that have more evolved business structures, and they are paying higher value for these businesses. Accordingly, the valuation process itself can provide guideposts to owners looking to increase business equity.

The continual use of practice valuations can also help practice owners monitor the equity built or lost from one year to the next, rather than just monitoring fluctuating cash flows. In fact, obtaining an annual valuation is one of the most beneficial strategies for growing a business, as investment professionals who have their practices valued annually tend to keep equity management in mind through every business decision. And don’t forget: Equity value is likely the largest number that you can add to your personal financial statements of net worth. That is an important consideration even from the aspect of a next generation, minority owner who is part of your succession plan.

There are a number of ways to place an accurate and authoritative value on a professional services business, including those in the financial services industry. Accepting that every valuation is an estimate until a buyer accepts and pays the price, the important questions can quickly be reduced to these:

- How accurate is a given valuation approach?

- How much does it cost to obtain an accurate valuation?

- Since almost no buyer pays all cash in this industry, how do the deal terms affect the valuation opinion?

Without positive and affordable answers to these questions, many practices and businesses in this industry would have no choice but to use a rule of thumb approach. Fortunately, there are good answers and at least a couple of well-accepted approaches when it comes to determining the equity value of an independent financial services practice or business.

In the financial services industry, it is relatively easy to discern a valuation multiple—at least in hindsight. Looking back over the past five years, the multiple paid for every dollar of recurring revenue (management fees and insurance renewal commissions, or trails) by third-party buyers ranged from a low of just under 1.5 to a high of almost 3.0. The multiple paid by third-party buyers for every dollar of nonrecurring revenue ranged from a low of about 0.2 to 1.7. That means that for the average fee-based practice or business in this industry, the range of multiples is from roughly 0.2 to 3.0. So go ahead and guess. You’ll be wrong, but by how much?

Let’s put this in perspective. If you have $125,000 in gross revenue or GDC and you’re wrong on your valuation guess by just 20 percent, you’ll cost yourself less than $40,000. If you own a practice worth closer to $1 million, the margin of error, in terms of dollars, will easily hit six figures. Given that most accurate, professional valuations used by advisors cost less than $2,500, it seems almost silly to belabor the point. Obtain a formal valuation as the first step in your planning process. If you’re thinking of selling and walking away (or fading away), the same rule applies.

The goal of a professional valuation is to approximate closely a given business’s fair market value. Fair market value has been defined as the price at which a property or asset passes between a willing buyer and a willing seller, with neither under any compulsion to buy or to sell, and both with knowledge of all relevant facts. Of course, where less than the entire ownership interest is being acquired, discounts may be applied to reflect the lack of control or lack of marketability.

Traditionally, a formal business appraisal uses a standardized format and one or more of these valuation techniques:

- Asset approach

- Market approach (multiple of revenue, multiple of earnings before interest and taxes/earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization [EBIT/EBITDA], or comparable sales)

- Income approach (present value of discounted future cash flows)

Many of the tools of traditional business appraisals are poorly suited for valuing a dynamic, fluid, and personality-based business like an independent financial services practice. The least appropriate of the traditional valuation approaches is the asset-based approach. This method is not applicable to financial services practices, because there are relatively few tangible assets (computers, copier machines, and file cabinets) in such a model. In contrast, the real value of a financial services practice lies in the strength of the client relationships and the transferability of those relationships, which, in turn, generates the future cash flow of the growing and enduring business.

At the other end of the spectrum, the income approach analyzes the earnings of a given practice or business; it is “bottom-line, looking up.” This method uses a going-concern approach, assuming that the firm will continue into perpetuity. Earnings-based appraisals work best for larger businesses and are well suited for those businesses of approximately $20 million or more in value. This approach also finds a practical application in support of an internal ownership track where advisor/investors purchase a minority interest of stock in a financial services or advisory business. One challenge with the income approach lies in trying to accurately and consistently define what income is.

A second and more serious problem with the income approach is its cost. These valuations are accurate and very useful, to be certain, but they tend to cost between $10,000 and $35,000, depending on the circumstances, the purpose of the valuation, and the appraiser’s skills and credentials. At this cost level, the income approach becomes problematic when used by next-generation advisor/investors to track the value of their investments and to consider buying additional stock from year to year.

The market approach, which is the primary methodology of FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation system, determines the value of a financial services practice by comparing it to similar practices that have been sold in a competitive marketplace. It is “top-line, looking down.” This approach is intended to answer two specific questions:

- What will a buyer pay for this income stream in a competitive, open market environment?

- How will a buyer pay the seller the determined value? (That is, what are the deal terms?)

The analysis in the Comprehensive Valuation system is based on the standard currency of the independent financial services market, that of gross revenue (or gross dealer concession [GDC] under FINRA rules). This top-line approach reflects the common practice of buyers in the competitive open market, and makes comparisons from one practice to another far more accurate and consistent.

There is an assumption in the financial services industry that the skills of the buyer are fungible, and that, within reason, a professional can take over the practice and render approximately the same level of service and generate an equivalent level of client satisfaction. This assumption works because of the size of the marketplace. With a sufficient pool of talent to draw on, successful and experienced financial professionals can be found who have reasonably similar levels of education and experience. As such, it can be assumed not only that a buyer with the requisite skills can be found for a given practice, but also that many buyers can be found that possess the necessary and complementary skills.

This result shifts the focus of valuation almost completely to the client base being acquired and the revenue stream that results, and not how the services are delivered, nor the cost efficiency of the services, nor even whether the practice provides a unique service in the community. The seller is simply transferring the client base, and therefore a valuation analysis is principally focused on the revenue potential of the client base being transferred.

FP Transitions’ approach is unique in terms of taking into account critical factors in assessing the strength and durability of the revenue streams of an independent financial services practice or business (see Figure 2.5). The first step is for the system to assess the transition risk for the subject practice. The next step is assessing the strength of the revenues of the subject practice, referred to as cash flow quality. The last step in determining value is to apply a market-driven capitalization rate to the adjusted GDC or gross revenue. This is the process that firmly links the valuation to market reality by applying capitalization rates that are keyed to the type of practice, its size, and, geographically, where in the country it is located. It should be noted that, as with the adjustments to transition risk and cash flow quality, none of the individual assessment factors tend to be large, but rather result in incremental adjustments to value and, in sum, produce results that closely mirror the reality of the marketplace as we see it every day.

Figure 2.5 Valuation Indexes

The indexes of transition risk, cash flow quality, and marketplace demand were first introduced to the independent financial services industry in a 2008 white paper commissioned by Pershing, LLC, entitled “Equity Management: Determining, Protecting, and Maximizing Practice Value.” Here is a closer look at some of the essential, underlying elements in FP Transitions’ industry-specific valuation approach that will help you better understand what drives value in the independent space.

Recurring versus Nonrecurring Revenue

Because the value of a business is based on the assumption of a continuing stream of revenue into the future, it is important that the analysis take into account the revenue sources—specifically, what proportion of the revenue is recurring versus transaction based. Fee income is the most important contributor to cash flow quality, as it represents recurring cash flow, which, in turn, is among the most predictable and durable of the revenue streams produced by a financial services practice. Recurring revenues also are the most important revenue streams to a potential acquirer or successor, and hence these fee-based revenues usually generate the highest interest and value. From a valuation perspective, these revenue categories form an important starting point for determining value.

Recurring revenue is one of the most important single determinants of value of a financial services practice. Revenue produced through management fees or trails is ongoing and reasonably predictable, and highly sought after by buyers. In the case of insurance renewal commissions, or trails, these are considered only to the extent that they can be transferred to a buyer. Most insurance trails are restrictive in terms of their transfer. While the assessments used in the FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation system are applied to both recurring and nonrecurring revenue, more weight is placed on the recurring revenue component.

Transactional revenue is more elusive and difficult to predict. Transactional revenue does have a value, but it is essential to be able to show the propensity for additional revenue in the future and during the buyout period. Factors like the practice’s historical revenue, rate of revenue growth, length of surrender periods, and quality of the relationship are instrumental in predicting this potential from transactional revenue. Due to FINRA/Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulations, there are certain inherent limitations on the transfer and payment for transactional securities revenue streams from a buyer’s perspective. For the insurance portion of a business, the client relationship index and client wealth index are used to predict the propensity for future sales from the existing client base.

Cash Flow Quality Factors

The quality of the revenue stream produced by an independent’s practice or business is one of the key components of value. The cash flow quality index, introduced and used exclusively by FP Transitions, indicates the strength and durability of the revenue stream of a practice. These factors, addressed in the following paragraphs, include:

- Client demographics

- Asset concentration

- Revenue growth and new client growth

- Expenses

In looking at client demographics, statistically it is desirable from a value or equity standpoint to have the largest proportion of the clients in the 50 to 70 years of age bracket, while at the same time not having a large percentage of clients in the 70 years or older age group. This is a recurring trait we see in the largest and best-run financial services practices. The 50 to 70 years of age demographic is desirable because this group, in general, is not only at the top of their earning cycle, but also at the top of the saving cycle as well. Event drawdowns, such as purchasing a home, paying for college tuition, or making business investments, are less frequent in this age group, while the urgency of saving as retirement approaches becomes more salient.

The demographics of those clients in the 30 to 50 years of age bracket are also important, contributing to a developing revenue base. In our benchmark studies, this age group does not represent the majority or largest group of clients, at least in the most valuable practice models. The demographic group represented by those clients 70 years of age and older is often the wealthiest segment in a financial services practice or business. This group, however, is a less stable and less predictable source of long-term revenue as this group is subject to event drawdowns for trust disbursements, gifting, living expenses, health issues, and, of course, mortality. In practices where the majority of the clients fall into the 70-plus age group, the result would be a lower cash flow quality rating, and, depending on other related factors, usually a lower value.

Asset concentration is another consideration in calculating the cash flow quality rating; it is measured by assessing the total percentage of assets under management owned by the largest top 10 percent of a practice’s clients (ranked in order of fees paid).

Revenue growth and net new client growth are significant contributing factors to cash flow quality as well and are measured separately. In our analysis, computed from information we collect from our clients, average annual revenue growth over the 2002–2011 period was 13 percent (evaluated as 5-year compound annual growth rates over the 2002–2011 period), with the middle 50 percent of the distribution growing by between 5 percent and 16 percent annually. The rate of revenue growth, however, is strongly influenced by market performance and therefore, by itself, is not a reliable indicator of the long-term strength of the cash flow. Net client growth, however, provides an excellent proxy for determining the future growth potential of the practice, as well as helping to determine the quality and strength of the referral channels and the client development systems that the practice has in place.

Practice expenses are taken into account as well in determining cash flow quality. Practice expenses are defined by the valuation model as (1) occupancy cost; (2) office overhead; (3) employee salaries, wages, and benefits; (4) marketing expenses; and (5) other or miscellaneous expenses. While the Comprehensive Valuation system does not use expenses to calculate net cash flows due to the variation in how expenses are classified and the difficulty of obtaining comparable statistics, the system does take into account expenses with regard to their impact on cash flow quality.

Transition Risk Factors

Transition risk is defined as the risk associated with transferring the clients, and hence the revenue stream, to a new owner or successor. A number of factors are involved in accurately assessing transition risk, including:

- Client tenure

- The tenure of the practice

- The willingness of the departing advisor to offer postclosing assistance

- The use of noncompete/nonsolicitation agreements

- Other factors such as remaining with the same broker-dealer or custodian, and a number of related continuity issues

The effect on valuation of the assessment of transition risk is to discount anticipated revenue transfer by the risk factor associated with the transition to a subsequent owner or successor. On average, experience dictates that in a well-structured, well-documented transaction, the level of transition risk is in the range of 5 percent, meaning that 95 percent of the clients and revenue will make the transition to the new owner. This number, however, has wide variation depending on the factors cited earlier, and therefore requires careful consideration in ascertaining the level of risk associated with a particular practice.

In general, the longer the client has been with a given independent practice or business, the less likely it is that the client will leave following an ownership transition without significant cause. Long-term clients are much more likely to stay through an ownership transition (whether to a third party or internally to other partners, managers, or employees); this is particularly true if the assistance of the selling owner has been structured into the transaction, or is part of an internal succession plan. This is a case of inertia working to the advantage of the transition.

A corollary determining factor for transition risk is the tenure of the financial advisory practice itself. The longer and better established the practice is, the less likely the clients are to leave the firm in the event of an ownership transition. A number of reasons may be attributed to this observation. In longer-tenured practices, the clients may associate the services more with the firm and less with any one individual, thereby making a change in ownership easier and more natural; longer-tenured firms also have acquired a marketplace reputation and position (often referred to as goodwill) that carries through in the event of a well-structured and professionally executed transaction.

The degree that technology is used in the office also factors into transition risk. In practices where there is a high technology level and where the owners have invested the time, money, and resources into the business component, the common result is that client contacts and tracking are more automated and in many cases more systematic as well. In these practices, the transfer of ownership often experiences less disruption than when the contact, processing, and office systems are not as highly automated.

Other ancillary factors that contribute to the transition risk assessment include the owner’s willingness to grant noncompetition/nonsolicitation/no service agreements upon their retirement or exit, and having similar restrictive covenants in place with licensed employees.

Marketplace Demand Factors

Since value is ultimately determined in the open marketplace by what buyers will pay a seller for an independent financial services practice or business, it is important to consider the market demand factors that influence that value. There are several important factors in determining marketplace demand, including:

- The type of practice

- Geographic location

- Size

The first consideration, practice type, is categorized by whether the practice is transaction based, fee based, or fee only. It can generally be said that the higher the percentage of fee income, the higher the demand for the practice, and this is factored into FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation model. The caveat to this classification is whether the practice has a truly specialized niche, which, while often lucrative (and which may increase cash flow quality), can have the effect of lowering marketplace demand because the practice may appeal to a very narrow range of potential acquirers.

As for geographic demand considerations, it is simply a matter of a buyer’s preference as to location. Practices that are located in highly desirable areas (which almost invariably means strong marketplace demographics) have higher demand than practices in rural or lower demographic profile locations. Geographic location has several other interesting aspects to consider. One is that when we list a fee-based practice for sale in Chicago, for instance, for $900,000, it will draw an average of 30 to 50 interested buyers from the general area. If we list the same practice for sale in Scottsdale, Arizona, we see an average of 30 to 50 interested buyers from the general area, and another 30 to 50 interested buyers from many of the colder-weather states.

Finally, the amount of revenue generated by an independent practice or business is an important consideration in determining market demand. This factor tends to be a matter of supply and demand; since the number of successful larger businesses that come on the market is far smaller than the number of lower-revenue practices, there is an asymmetry in supply, which tilts the demand equation in favor of larger sellers in the current marketplace.

Very small practices, those having revenues of less than $200,000, and businesses that have revenues in excess of $1 million per year also have a higher demand factor than those practices in between those revenue levels; one is easily affordable, and the other is more about quality. These demonstrated preferences over the years are accounted for in the market demand index, though it should be noted that the cash flow quality factors and transition risk factors may offset this advantage.

Addressing Insurance-Based Practices

The valuation of an insurance-based practice is different from any other type of valuation we perform. As a beginning, recall that the valuation of a financial services practice or business must address the following basics in order to provide an accurate assessment and useful business-building tool:

- The quality of the practice’s cash flow

- The ability to transfer the clients and assets to a succeeding advisor

- The marketplace demand for what the practitioner has built

In addition to these basic indexes (cash flow quality, transition risk, and marketplace demand), an insurance-based practice requires further analysis to address the depth and length of client relationships with protection-based clients—issues that directly affect the probability, and profitability, of future revenue events. This additional level of study is referred to and quantified in the FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation system as the client relationship index (CRI).

There are many factors used to accurately establish a practice’s client relationship index, but basically the CRI is divided into three primary subcategories for evaluation:

- Client adhesion

- Business systems

- Client management

Separately, no one of these subcategories of the client relationship index significantly affects the overall adjustment to the valuation results of a financial services practice, but collectively, the sum of these factors provides a reliable guide to the overall quality of the client relationships and therefore the book’s ability to generate future revenue events. Since the client relationship itself is the primary driver for predicted future conversions, a renewed focus on how this relationship is managed—now and in the future—is a critical aspect in establishing and even increasing the value of an insurance-based practice.

Impact on Value of the Payment Terms

The results of the FP Transitions’ Comprehensive Valuation attempt not only to value the practice or business, but also to place the value within the context of commonly utilized deal structures and payment terms. The reason for this is that one of the most important components in a practice valuation in this industry is the structure of the transaction; practice valuations are inextricably linked to the deal terms. Comparing values or developing pricing for a financial services practice or business in the absence of understanding and employing the appropriate deal structure, which includes the tax allocations, can be very misleading.

The primary lending or financing source in this industry is the exiting or affected owners themselves or, for larger firms, the business enterprise; this is often referred to as “seller financing.” (This is true for both internal and external transactions.) Seller financing, in turn, means that practice sales and acquisitions require a degree of cooperation and flexibility between the parties before the transaction is completed and for a period of time afterward, what we refer to as an “economic marriage.”

Seller or company financing also means that retiring practice owners look to their successors for more than just the highest purchase price or the largest down payment. In a seller-financed transaction, buyers rely heavily on their own cash reserves or lines of credit for the down payment, and on seller financing to pay for the balance of the purchase price. In sum, it takes buyer and seller, in a cooperative effort, to make most transactions, internal or external, financially viable. This codependence often results in sellers choosing very highly qualified buyers (rather than the highest bidders) who are excellent matches in terms of practice style, business model, investment philosophy, and personality, which, in turn, often results in very high client retention rates, supporting the realization of highest value for the seller.

Deal structuring represents the apportionment of risk in the transaction between buyer and seller. The payment terms that underlie the determined value in our Comprehensive Valuation Report represent the most commonly utilized deal structuring approaches. The basic components used to finance a transaction or to structure a deal include a cash down payment, a basic promissory note, or a performance-based or adjustable note; earn-out arrangements are rarely used anymore and should be avoided by FINRA-regulated practices.

Profitability and Its Impact on Value

The value of an independent financial services or advisory practice has traditionally been driven by top-line revenue, as illustrated in the preceding pages. The ability to access that value in the succession planning process is driven by bottom-line revenue because of the internal ownership buy-in process. In other words, if you cannot consistently generate a reasonable profit, you cannot build a valuable and enduring business.

From the internal buyer’s or investor’s perspective, the business’s profits serve a critical function in almost every case; profit distributions are the primary funding source for their buy-in. Profits are the source of money they will use to make the promissory note payments to purchase stock or an ownership interest from the founder or from the business itself. Profits also serve as a return on investment both for you (the founding owner) and for the incoming partners who are taking on the roles and risks of a formal business relationship. A business that distributes most of the incoming revenue on a revenue-sharing basis tends to have a nominal bottom line. In that common instance, next-generation advisors have little choice but to invest in a job, or building their own book, rather than your business; a paycheck or a share of revenue is the only way to earn a return on investment.

The point is, as a business owner, you have to find a balance between the top line and the bottom line if you’re going to attract and retain collaborative business partners and next-generation advisor/investors. What is that balance? In our experience and based on our study of actual business models, we think the minimum level of profitability to sustain an enduring business model is 20 percent. Said another way, at least 20 percent of the business’s gross revenue needs to make it to the profit line and be distributed to actual owners. In an S corporation, for example, profit distributions are tied to investment and risk, not to production. Profits serve as the return on investment for those who actually take the risk of investing in a business and creating the infrastructure necessary to endure.

The impact on value is this: When profits are lower than 20 percent, equity value, at least in the eyes of an internal advisor/investor, is reduced. As profitability increases, equity value is increased, as is the advisor/investor’s ability to purchase ownership, which brings us full circle—the ability to access value is driven by bottom-line revenue.

Many practices, as they begin to transform into businesses, simply cannot achieve a significant level of profitability, and that is okay. Shifting from a revenue-sharing, one-generational practice is not supposed to be an overnight proposition. But work toward that goal. Succession plans have the added benefit of creating a long-term strategic growth plan for cash flow and equity.

Later in this book, we’ll share an excellent strategy for achieving and even surpassing that 20 percent goal. Eventually, the profit line should be 30 percent or more to reward and attract ownership-level talent and to create a single, enduring business model. In terms of what the right profit level is for your business or firm, think of it as an investor would—after all, that is what you’re trained to do as a financial services professional. As our valuation models become more sophisticated from year to year, as we learn alongside you, the profitability element will become more prominent and serve to provide a more accurate assessment of value from an investor’s point of view.

For the methodology and the actual math on this concept, see the last two sections of Chapter 3, “Remodeling Your Cash Flow” and “Production Model versus Business Model.”

Practicing Equity Management

The very notion of practice management means you’re accepting limits on what you can build; managing a practice means it will die with you, or sooner upon your retirement. It means you’ve settled for building a one-generational income stream and then will leave your clients to figure out the rest. This isn’t about semantics. Practices don’t last, and this industry needs businesses that are built to last—enduring and transferable businesses.

As an industry, we need to start thinking bigger and smarter, and longer term. An industry of entrepreneurs is perfectly suited to doing just that, but to build a valuable and enduring business, you will need new tools and an approach that is focused on what makes an independently owned model different—equity. Say hello to the concept of equity management.

The term equity management was first used in 2007 in a research report published by FP Transitions. In that report, the concept of equity management was defined as follows:

Equity management is a concept focused on helping owners determine, protect, and optimize the value of their independent financial service practices. To accomplish these tasks, the process of managing practice equity necessarily includes building a business structure that can outlive the founding owner by integrating the next generation of advisory talent through hiring, practice acquisition, or merging.

Professionally managing the equity in an independent business model can be condensed into five basic steps (see Figure 2.6) that maximize the value of the business for the individual advisor and create stability, predictability, and retention of clients and assets for the broker-dealer or custodian:

- Determine and monitor business value.

- Properly structure the entity, organization, and compensation systems.

- Establish a continuity protection plan.

- Generate strong and sustainable growth.

- Transition leadership and ownership gradually as value is realized.

Figure 2.6 Managing the Equity in Your Practice

Managing equity is also intended to help you attract and retain next-generation talent, not just as producers, but as collaborative partners who may one day form your succession team. It is focused on helping practice owners monitor, protect, and realize the value of their life’s work while providing for the long-term care and retention of the clients they serve. Most important, it transforms how advisors and their broker-dealers view a financial services practice, shifting from a vocation to a business of enduring value. If your broker-dealer’s or custodian’s practice management consultant doesn’t talk to you about equity, or can’t speak authoritatively on that subject, you’re likely wasting your time. Equity management is how you transform a practice into a business—without it, you’re simply talking about what size of practice you want to be constrained to.

In the end, doing what is right for the clients and doing what is best for the business are mutually dependent concepts. In fact, the only way to ensure that the value of a practice based on intangible assets (such as client relationships) will be fully realized by the founding owner is to provide for a seamless, gradual, and professional transition to a successor or succession team that has a clear understanding of the future needs of the clients, along with an enduring business and supporting staff. The creation and maintenance of this framework is called an equity management system.

Most of today’s independent advisors are still focused on managing only cash flow, because that is the focus when running a one-person practice. The problem is that you need next-generation talent to invest their time, money, and careers to build on top of what you’ve started in order to create a valuable and enduring business, and advisors don’t invest in cash flow. Remember, if the goal is to own a job, next-generation advisors can accomplish that almost anywhere. Equity is long term, and it shifts the focus from individual books to a single strong enterprise. But to get there, that equity has to be professionally managed and valued.

The starting place? Formal, annual valuations that determine equity value, that support a plan for growth and endurance, and that utilize the benefits of both cash flow and equity to reward and retain next-generation talent.

Building Profit-Driven Businesses

Instead of building businesses that evolve and improve from one generation to the next, advisors in this industry tend to build, and subsequently rebuild from scratch with each new generation of owners, largely because of the eat-what-you-kill compensation system; this compensation approach, coupled with various FINRA rules and a production- or sales-first culture, leads to a sole proprietorship mentality and an emphasis on top-line production.

So how do you structure ownership-level compensation designed to build enterprise strength into a single, equity-centric business rather than growing several individual books of business under one roof? You start by shifting the focus to the bottom line: profits. Profits attract advisors who will work for you in exchange for an ownership opportunity and the ability to build on your foundation.

That seems like such a simple statement, such a natural and normal thing to do; almost every business that achieves any level of success focuses on profitability and sharing those profits with the equity partners. This step has not occurred for 99 percent of today’s independent advisors because the thinking is still that of owning a job; a job doesn’t have a bottom line, and it doesn’t need one, because it has a short lifetime and no successors; it is about cash flow and cash flow alone. Shifting the focus from production to profitability is a critical part of the evolution of this industry; if this step isn’t taken, almost every practice in this industry will work only as long as the owner and largest producer works. Collectively, we’ll continue to build revenue mills instead of enduring businesses.

Profits—actual profit distribution checks issued by the business on a regular basis and restricted to those who become equity partners—will gradually shift the focus of the production mentality to thinking and acting like an owner. This will also attract advisors who wish to become owners. Remember, advisors currently have no need to invest in your business to obtain a share of revenue—they just show up and work. If the top line is controlled a little more tightly (not reduced, just controlled), and profits are paid out only to those who become equity partners, there is a great reason to take the additional step and to buy into the ownership circle. The risk has a reward, as it should.

Building a practice requires a focus on production or revenue generation; that’s true in almost all small businesses. Building an enduring business requires past and future leadership to make the connection between a growing cash flow stream and the costs of such growth—in other words, a focus on the bottom line. In the independent sector, if the goal is to build a valuable and enduring business, the focus should be on a team of advisors working together, compensated for contributing to and supporting a single enterprise, rather than building individual books of business and then leaving with them and the cash flows they generate when the time is right. Structuring compensation to motivate ownership behavior and thinking is one of the keys to building a foundation for a successful succession plan.