Chapter 4

Creating Your Succession Team

The People Problem

So by now, at least figuratively speaking, you’ve set up the correct entity structure, and you have an organizational structure and a modern compensation system designed to support an enduring and transferable business. But you’re still the sole owner (or perhaps one of several owners without a clear plan). Having built the foundation for a successful succession plan, how do you convince the next generation to get on board (as business owners and investors in one, single business) your ship?

Let’s just ask it out loud: Will the next generation invest in what you’ve built? Does it make more sense for them to hang out their own shingle or to build on top of what you’ve spent the past 10, 20, or 30 years building and growing? These are good, tough questions; let’s make them harder, and more relevant: Why would a producer who makes $250,000 a year or more, who has no or minimal responsibilities for hiring, firing, signing leases, negotiating leasehold improvements, or worrying about payroll, want to become an investor, a minority owner in your business? Those are the issues that we’re going to focus on in this chapter.

So, what are the answers? Well, for starters, understand that you can offer a very unique investment opportunity, and you will need to learn to articulate it once your plans are complete. Think of it this way: How many investments can a younger advisor make that come with a mentor and a paycheck, and pay for themselves over time? How many active investments start out with the goal of not impacting the investor’s take-home pay and provide the investor with the means of giving himself or herself an automatic raise by helping the business grow? A good succession plan will do all of these things.

Remember those first couple of years of self-employment as an independent advisor and the size of the paycheck you received, even after some very long and trying days? You have the ability now, with experience, to help others avoid that pitfall, and that’s worth something (it’s worth a lot, actually). And that is just one of the reasons that the ownership circle is a special place; not everyone gains admittance.

To build an enduring business, you need more than one owner; it takes people, good people, which is why this may very well be the hardest part of the process. It is impossible to perpetuate a small business without the help and support of next-generation talent. That much is obvious. The more challenging aspects are often summed up in these basic, but often asked questions:

- How do I hire and retain employees with an entrepreneurial mind-set?

- How do I sell or gradually transfer the business to employees who have no extra money to invest?

- What if my internal ownership plan doesn’t work out?

Many founding owners struggle with these issues, but the real concern may be better stated as: “How do I find people who will work as hard and care as much about this business as I do?” Too often, however, that question is framed to generate a nearly impossible answer in support of a self-fulfilling prophecy. As the founder, there is only one of you; there will never be another. You’re the entrepreneur, and the only one your business will ever need. Entrepreneurs have to do it all in the early years of building a practice, but that process is usually augmented by having a very short and efficient chain of command. The next generation must work collaboratively, as a team, to accomplish its goals—not an easier or a harder task, but very different from what most entrepreneurs in this industry have to do. Regardless, if you don’t find a way to share what you’ve spent a lifetime learning, your practice and your knowledge will die with you.

The better and more exciting news may be this: Creating and supporting an internal ownership track, one designed to support the most common “Lifestyle Succession Plans,” as we call them, isn’t about replacing you as the founder. Rather, the process is about taking the best of your talents and experiences and using them to build a business of enduring value, something that can outlive you and serve your trusting clients for generations to come. With that goal in mind, let’s start with the basics and solve the people problem: Where do you find the talent to form your succession team?

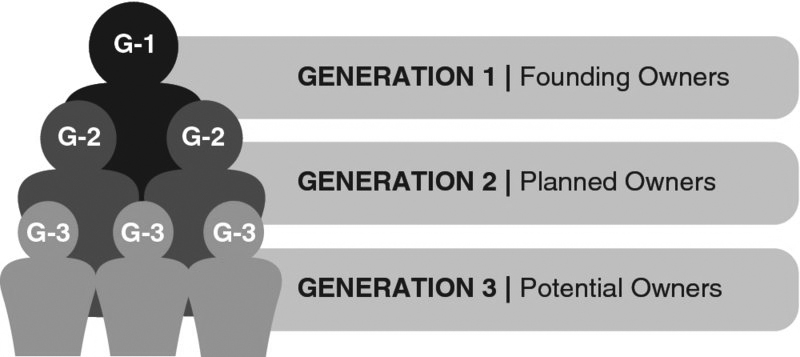

The Secret Formula: G-1 + G-2 + G-3

One of the consistent points in this book is that independent owners need modern and appropriate tools to work with to build multigenerational businesses—not the tools they’ve learned to use from the wirehouse side of the industry. To this end, we’d like to introduce some terminology to help you navigate through the people problem. We label these terms “G-1,” “G-2,” and “G-3.” (See Figure 4.1.)

Figure 4.1 Building a Multi-Generational Business

Every succession plan is designed around the unique goals of the founder, whom we call G-1, for Generation One. In the case where there are multiple owners and founders within five years of each other’s ages, they are all G-1s. Referencing Figure 4.1 as a general illustration, you’ll need to create a succession team, a group of younger owners—all equity partners who buy their way in to the ownership circle, often one at a time. Let’s start with Generation Two, or G-2.

Ideally, you’re looking for two people at the G-2 level for every owner at the G-1 level, and three people at the G-3 level for every owner at the G-1 level. The perfect age difference between G-1 and G-2 is about 15 years (plus or minus five years); it does not require a family generation, though we frequently see that fact pattern as well. If there are two or more senior owners within five years of each other’s age, their average age is the reference point to use when looking for the G-2 personnel for your succession team. It is not necessary that you start your plan with two G-2 advisors right out of the gate for every G-1 level owner; you can solve this problem over the course of the first five years of the plan, but it is important to eventually diversify your risk with a minimum of two G-2 level prospects. In the event that the G-2s are much younger than the ideal, defer to their capabilities and potential rather than age. To paraphrase the late President Reagan, don’t hold their youth and inexperience against them.

Why is it important to widen the ownership base? There are three answers to that question that are equally relevant:

- Continuity planning. If, five years into the plan, G-1 has to buy out G-2 because G-2 had a skiing accident or a car accident or quits, the succession plan will shift into dead reverse. G-2 needs a continuity plan that relies on the other G-2 owner(s), not the founder (G-1), who has a gradual retirement in mind and is in the process of selling off his or her ownership gradually over the next 10 to 20 years to the succession team.

- Diversifying G-1’s risk. Many G-1s think that the biggest problem to solve is where G-2 will get the money to buy them out. That is incorrect. The problem is one of tenure. In other words, how do you get a 20- or 30-year-old to make a career-length investment? The fact is, they may not stick with it. Having more than one G-2 owner not only diversifies the risk that one advisor may leave, but it also creates some friendly competition and ensures that the best talent is available to the clients and to lead the business in the years to come.

- Diversifying G-2’s and G-3’s risk. Buying out G-1’s position by paying, in many cases, seven figures of value with after-tax dollars, and trying to track down a business that is growing and accelerating away from the internal buyers, who often have no significant cash reserves at their disposal, is a tall order. Dividing that task among a group of collaborative investors is smart work and smart investing.

Let’s stop here and clarify some important points. Most succession plans do not include the sale of the entire practice all at once to a single younger advisor. That scenario is possible, and we’ve helped advisors successfully do it, but that is more of an exit strategy or an outright sale, not a succession plan. A succession plan is designed to build a multigenerational business by gradually transferring ownership and leadership to a team of next-generation advisors.

G-2 advisors, the most senior members of your succession team, are almost always producers or, if you don’t like that term, independent owners who are capable of generating revenue for the business by providing advice and services or selling product. Prospective owners who are a part of a fee-only business (Registered Investment Advisers [RIAs]) don’t need to be licensed or able to produce revenue, but they usually are since that is a primary source of their funding to buy your ownership interests, or stock; if you’re Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) regulated, we recommend restricting the succession team to those who are properly and similarly licensed. For those who are with an independent broker-dealer or insurance company that has unlicensed key staff members, the use of a phantom stock plan may be the better choice for those particular staff members.

If the plan unfolds successfully, it should be G-2’s responsibility to hire, train, and retain the G-3 level succession team, with guidance from G-1 of course. The G-3 level owners will be the future business partners for G-2, so let them make some of these decisions, right or wrong. It is part of the learning process for the next generation of business owners, and it is how most G-1s learned how to hire the best people at the G-2 level to succeed them.

Many owners ask us when G-2 should become eligible for an ownership opportunity. How long does a G-2 prospect need to work for you before becoming an equity partner? Our experience is that the time frame in this industry needs to be shorter, at least at this time, than in most other professional service industries where five-plus years is the norm. Advisors are starting late and are in an industry that still encourages separate book building; until that culture significantly changes, plan on working a little harder, and faster, to keep and propel great talent that you have on board or that comes your way. We think that ownership opportunities should be extended to G-2 in years 3 through 5 of full-time employment. For G-3, the partnership track should be extended a bit, probably to around four to six years of full-time employment before a partnership buy-in opportunity is extended.

If you have the opportunity to pick up a great prospect who has just graduated from Texas Tech University or a similar four-year program with a bachelor of science in personal financial planning and at a reasonable cost, do it. Developing a G-3 prospect or two is smart, if you can afford it, but do it as a part of a formal plan. Put them on a W-2 compensation system, share with them your plans for building an enduring business, and see how it goes. It’s okay to plug in the talent at all levels and at various intervals. It isn’t about the timing; it’s about the quality of the people you surround yourself with, and the sooner you do that, the better.

Plan Before You Build and Hire

When I was in my thirties and had a lot more energy, I used to run long distances, for fun and relaxation. On a Saturday morning, I would routinely run 10 miles or more. On one occasion, I was deep in thought as I ran, mile after mile, and I got lost. (In the days before cell phones, it was a lot easier to do!) Being a little tired and disoriented, I quickly decided to choose the most logical direction and keep on running because it felt good to make progress. But a few miles later, I realized I wasn’t making progress by continuing to run in a wrong direction—I was just making the problem worse and slowly running out of energy and daylight. It was time to stop, reassess the situation, and maybe walk for a bit until the path became clearer, which it did.

One of the common refrains we hear from advisors is this: “I don’t have anyone who works for me who is ownership material. I’ve hired a number of people over the years, and most end up being competitors.” That shouldn’t come as a surprise, in that most likely you didn’t hire or train any of these folks to be part of your succession team, let alone to build an enduring business. Hiring a producer/advisor who could become the future CEO of your business, at twice its current size, isn’t a matter of luck. Still, regardless of your current talent situation, or maybe in spite of it, you should restart the process with a formal, written plan that lays out what talent you’re going to need, and when you’re likely to need it. A sample succession plan schematic is provided in Figure 4.2.

For many advisors, typically those around age 50 or more and who also find themselves in business-building mode, succession planning often ends up being the cornerstone of a strategic growth strategy designed to perpetuate the business and the income streams beyond the founder’s lifetime. It is the succession planning process, interestingly enough, that is used to assess and fix the structural issues necessary to retain or onboard the necessary next-generation talent.

The real starting point in the business building process requires a focus on two primary areas of work that ideally begin at least another five to 10 years before the succession plan is even launched (think closer to age 40), if not when the practice is initially set up. The two broad-based areas to plan and build around are these:

- Organizational structuring, which includes creating an equity-centric organization, making your entity investor-friendly, and setting up a professional compensation system for those at the ownership level.

- Optimizing business resources, which is designed to produce strong, sustainable growth; this is about the people it takes to run a multigenerational business—how to attract them, reward them, and keep them on board for a lifetime.

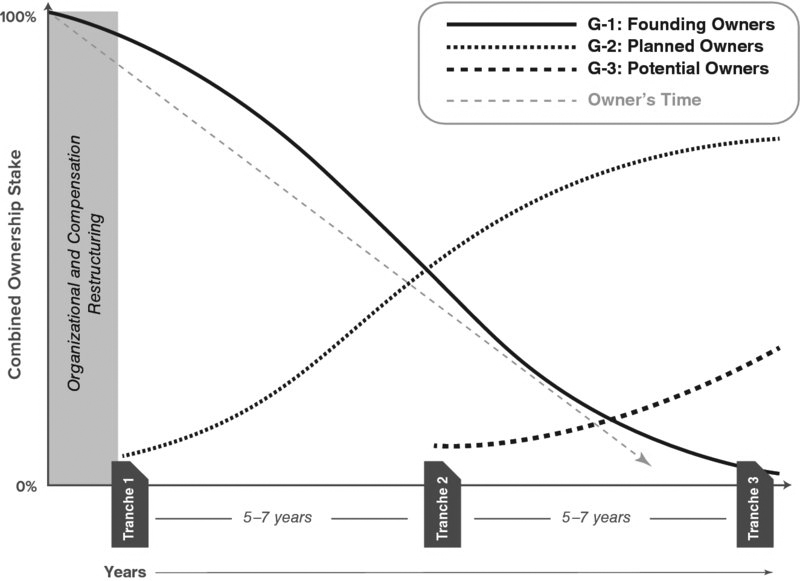

These items have to be attended to before a formal, written succession plan can be launched (note the far left, gray box in Figure 4.2), but the benefit of implementing these steps goes far beyond the issues surrounding a founding owner’s gradual retirement. These are powerful business-building steps, and it is never too soon to start doing things right. The limitations on today’s first generation of retiring owners are similar to those on typical advisory clients who first start planning for retirement five to 10 years before they want to start enjoying all the benefits of a lifetime of work and savings. That’s not much time to plan with, and even with a great plan, the results have a self-imposed ceiling because of the limited time frame.

Figure 4.2 Succession Planning Schematic

The goal of most succession plans is to make the business work for you, instead of the other way around. One of the most important steps in the process of building an enduring and transferable business is to build an investor-worthy enterprise designed from the outset to attract, retain, and empower next-generation talent. Building the foundation should start at around age 40 for the founder, or when the founding team is, on average, around age 40; this gives you an extra 10 years, or more, to solve many of these problems and, more or less, makes succession planning an easy problem to solve. It shifts the problem from building to where it belongs: planning for the future. Build the foundations for success 10 years earlier than you intend to start your succession planning.

Mining the Talent Pool

The result of building the correct foundations for a valuable and enduring business and laying out a formal, written succession plan is that you will be able to offer a unique employment and career opportunity to the next generation of independent professionals. First, you’ll be able to offer an ownership opportunity with a built-in financing structure. Second, you will be able to offer not only a competitive wage, but also access to your company’s substantial future profit distributions for all partners. Finally, you’ll be able to offer them control over their future and an enhanced income stream (wages + profits + equity), with the added protection of a collaborative framework that ensures a sound continuity plan and succession plan.

That is a powerful package, but what happens if the next-generation talent isn’t buying what you’re selling? The norm in this industry, right or wrong, is an activity-based compensation package that rewards production. What about those advisors who refuse to work for anything other than a share of revenue or an eat-what-you-kill approach? The best answer is this: Go back to your plan and revisit the fundamentals and the goals. It is important that you understand how the pieces are linked together to create a strong framework for long-term success, to transform your practice into an enduring business. Then be prepared to explain it patiently and confidently.

When you share revenues, you exchange cash flow for equity. You receive, after expenses, the smaller share of the cash flow that has been produced, and you give away all of the equity value of the book (only to turn around and buy it back if the advisor later decides to come on board as an owner). If a revenue-sharing arrangement is what they really want, and they won’t listen to your point of view, may I suggest you send them down the street to your nearest competitor and let them take the equity out of someone else’s practice? Unless you are trying to build a wirehouse of your own, you don’t benefit from a revenue-sharing arrangement as a business builder.

Over the past five years, we’ve had the very special opportunity to sit and privately talk to second- and third-generation advisors, G-2 and G-3 respectively, and to show them the plans we’ve come up with for G-1, the founder of the company. We explain how we valued the business they are being offered an ownership opportunity in, and how they can use this tool to track the annual value of their investment. We explain the upside and the downside of the investment opportunity, all without G-1 in the room.

We explain that the investment doesn’t start with a pay cut (their current take-home pay isn’t typically needed for the buy-in process), and that the success of the investment will require that they invest more than their money. The investments we’re looking for are tied to the strengths they bring to the table: their time, their energy, and their careers.

We show them the pro forma spreadsheet and what’s in it for them and what’s in it for their boss and the other members of the succession team that will need to be hired, trained, and who may earn and be offered a similar opportunity. We show them that by producing, and by growing the company, they control, to a large extent, their own means of compensation and paying off the obligations of purchasing equity and building wealth for themselves. We show them what we hope the future of their investment will look like—the nature of a pro forma—if they do their job as a collaborative, long-term business partner.

And then it gets more exciting. We invite them to return for a second call with their spouses, or significant others, or coaches, or whomever they turn to for advice when making big decisions. And we do it all over again. We do this with hundreds of G-2 and G-3 advisors every year, and 85 percent of them decide to invest and commit their careers or at least 10 years at a time to the process of building on top of an existing business, to build something as a team. They sign a stock purchase agreement and a promissory note, and they buy stock (or ownership interest in an LLC) from G-1. They agree to flatten their compensation at the wage level, and they turn to a share of profit distributions for their pay increases. Are they really ready for this? They think so!

In our conversations with founders of businesses in this industry years after implementing a succession plan and setting up the foundational structures, we hear them use terms like “rejuvenated” and “reenergized.” We see it in their growth rates. We hear it in their voices. Most G-1 level owners tell us that they’re beginning to work less hard, they’re doing more of the things they enjoy, and they think their careers will actually be extended, allowing them to contribute more and to really make a difference, while still throttling back on work hours and stress. These are the common goals of most succession plans.

Turning Employees into Equity Partners

The first place to look for your succession team talent is internally—the people who work for you now. While these folks probably weren’t hired or recruited with ownership and succession planning in mind, they still deserve to be considered and auditioned for this important opportunity, if it is done properly and as part of a well-structured plan. There are basically two kinds of internal staff members that can support the goals of a succession plan:

- Key employees/advisors without their own books

- Key employees/advisors with their own books

For the most part, when we refer to key employees or staff members, we mean that they are active participants who produce revenue and are therefore licensed, registered, or qualified to provide investment advice or sell various products or services. Fee-only RIAs have more latitude in this area, whereas FINRA-regulated advisors have less; either way, plans can usually be tailored to fit the circumstances.

Key staff members who do not have their own books tend to be paid on a W-2 basis (think salary and bonus), but form of payment is not material as the plan is initially designed and developed. Simply stated, consider the best staff members for an ownership opportunity almost regardless of age. Determine where an existing employee (or even a potential new hire) fits into your plan, or might fit with further growth and development. In doing so, picture your business at twice its current size (i.e., twice the cash flow, but understanding that doubling everything, including workload and expenses and number of clients, likely won’t be how you double in value). In that setting, where will you need additional help, what roles will you need to fill, how many hours will you want to be working at that time, and where will talent be needed to strengthen the business model?

It is a common mistake to conclude that a given employee isn’t an entrepreneur like the founder of the business, especially when the employee doesn’t have his or her own book. But honestly, doesn’t every successful advisor start from zero at some point in his or her career? The issue is that the founders often look for younger versions of themselves—an obvious chance to repeat a process that worked so well the first time. It bears repeating that building on top of an existing business is going to require a very different skill set than starting a business from scratch. An established business can present a truly unique investment opportunity for succeeding generations of advisors that does not require one person to do it all. It will take more than one person to run a great business.

Start slowly and slot your key staff member(s) in at G-2 or G-3 in your plan, and offer them an ownership opportunity. Plan on selling around 5 percent to 7.5 percent at most to each individual in this first round, and offer them 10-year seller financing. Do not give away ownership; it should be sold and purchased—this is part of the proving grounds. Remember, there are two sides to this investment opportunity, and while G-1 typically retains the roles of CEO and president, and is the majority owner at this point in the plan, the next generation has a decision to make, too. Don’t take the decision on whether to become an owner and invest a career out of their hands with a gift of ownership; both sides of this equation need to evaluate it on the merits and make the hard decision. Clearing this hurdle is often part of the process of valuing the opportunity and making it work. Strategic grants of stock can and often are still a part of the overall strategy, just not right out of the gate.

Are there hooks in this ownership opportunity? Absolutely; in fact, there’s a net over this ownership opportunity. Every next-generation purchase of stock (or ownership interest) is secured with a stock pledge, a restrictive continuity agreement, drag-along rights, penalties for not finishing the process, and so on. That said, don’t forget to plan adequately for success and to provide incentives for achieving your mutual goals. Many first-time purchases of ownership include friendly financing that is almost default-proof, and additional, small grants of stock over time (only after stock is first purchased and paid for), and sometimes a minority discount. All in all, it’s a pretty good deal.

FP Transitions’ Lifestyle Succession Plan relies on a multiple-tranche strategy that can be adjusted to create a long-term, flexible approach that results in a very gradual but significant reduction of the G-1 level advisor’s time spent in the business as the reins of leadership are earned and handed off. The process begins with the acquisition of stock by the G-2 level advisor(s) on a tranche basis (the number of tranches or steps are designed to fit the circumstances of the business and its owners, but two to five tranches are the norm for planning purposes) from G-1’s perspective. Appropriately, Tranche 1 is often called the incubator. It is designed to test whether the next-generation advisors you have on staff, or those you add to your staff, value this opportunity and investment as much as you do.

Tranche 2 may never happen, and it will happen only if the G-2 level owners prove themselves worthy in Tranche 1. If your plan doesn’t work out (and that’s a possibility), plan B is to position what you’ve built for sale or merger. Before you get to that point, recognize that setting up and administering an internal ownership track takes time, and sometimes you have to restart the process. The more time you give yourself, the more likely it is that you’ll get it right and create an excellent succession plan.

Onboarding Talent with a Book of Business

As for the second group, key staff members who have their own books, this can be a bit more treacherous, but often has much greater upside. This group is the most likely to form your G-2 contingent. It almost doesn’t matter whether the producer/advisor works for you directly as an employee, works under your roof as a contractor, or is a new or prospective recruit; onboarding an individual with his or her own book into an ownership slot in your growing business is a challenging but potentially lucrative maneuver. Understand that bringing this group into the owners’ circle will take a higher level of skill than the previous group and requires a better understanding of how the structural elements in your business work together to make it possible, and advantageous for both sides.

Advisors in this class are a proven commodity, at least in one respect. They can generate revenue. That does not and should not automatically qualify them for ownership, but it is a major consideration. The bigger questions that naturally follow are: Do they want to sacrifice the control they enjoy over their workdays and income stream in exchange for a minority ownership position, some significant debt, and the opportunity to build on top of your business? Can they do anything more than produce revenue? Are they a good fit with the rest of the team? Those can be tough questions to answer, but they are impossible to answer if you don’t have a plan for what you’re trying to build and that clearly illustrates the benefits for all involved.

We see three common scenarios when onboarding advisor/producers with their own books into an equity position:

- The book is small enough and the employer/employee relationship strong enough to make the issue irrelevant.

- The book is large enough and valuable enough that G-1 buys it with an exchange of ownership or very advantageous financing.

- The book is large enough and the advisor capable enough that he or she walks across the street and hangs out his or her own shingle, or legitimately threatens to rather than build on top of your business (“The Case of the Super Producer” is covered in the following section).

If you helped G-2 get started with knowledge and/or a contribution of your smaller clients, and if you don’t wait too long, and if the value and cash flow from the book is not too great (typically not more than about $150,000 in gross revenue, or GDC), it often isn’t difficult to onboard this talent level into an ownership position. Assuming that your plan provides the basic elements of seller financing at discounted levels and a profit-based note (at least in the first tranche), you have an excellent chance of making this level of advisor an equity partner. Granted, that is a pretty good list of “ifs,” but it is far better to try to build a collaborative, long-term relationship than watch yet another advisor/producer grow stronger and become your competitor. Develop a plan and give it a try, and don’t offer too many concessions; all in all, the opportunity is a good one for the next-generation advisor and he or she is in the business of taking advantage of good investments. Show the advisor your plan for the future and where they fit in. Remember, equity is a powerful draw, and you’ll see that in the pro forma models for your long-term plan—so will G-2.

In short order, here’s how it tends to work. The onboarding process starts with an evaluation period—with due diligence being performed in both directions. Remember the general timeframes from earlier—extend an ownership opportunity to G-2 in years 3 through 5 of full-time employment. For G-3, the partnership track should be extended a bit, probably around four to six years of full-time employment before a partnership buy-in opportunity is extended. Don’t keep your plans a secret—in fact, share your plans from the first interview on, and then see how it goes.

When the time comes to seriously consider an ownership opportunity, start by having your business and the advisor/producer’s practice formally valued (but only if their book is larger than about $150,000 in gross revenue or GDC), and then have two copies of the valuation results made and certified; share one complete copy with the other side (be sure to sign a nondisclosure agreement beforehand, and use a common valuation methodology). Share a copy of your comprehensive succession plan with your onboarding prospect and explain what you’re thinking, where the prospect fits in, and what’s in this for both of you.

If interest remains strong and it is a good match after additional thought and exploration, you’ll need to physically bring the two models together to operate side by side and under the same roof (if they aren’t already). This is not a merger or a marriage, just two owners moving in together to see if a permanent union is warranted and wise. This might sound quaint or old-fashioned, but this is a big step, and creating a permanent equity partner out of a satellite office with someone you only talk to over the phone is often impractical and unworkable, at least if your goal is to build one strong enduring business.

If it works out, the owner of the book, the prospective G-2 producer/advisor, will sign a contribution agreement and contribute all right, title, and interest in the book to your business. Your business, in exchange, can use its treasury stock (authorized but unissued shares) to purchase the book, often using the respective values of the business and the book to determine the correct ownership ratio, or at least to form the starting point for the negotiations. On this point, G-1 often argues that G-2 has no infrastructure and no “real business,” and that somehow that mitigates or even eliminates any value to the G-2 book. That is a good argument, but it almost always loses. The simple retort is that G-2 won’t do that deal and sacrifice autonomy and control over his or her cash flow for an at-will employment situation and a minority ownership position and a formal debt obligation, and why would they?

The bigger issue is taxes. If you are set up or taxed as an S corporation, the owner of the book of business who exchanges what that advisor/producer has built for an ownership position in your business is taxed on the fair market value of the stock received just as if he or she had sold the book and been paid for it (from the IRS’s perspective, that is exactly what happens). That’s a nonstarter for G-2 unless the transaction also includes a significant cash payment, which tends to make it a nonstarter for G-1 as well. The more common solution for this problem goes back to the element of long-term, friendly financing and the ability to buy in on a discounted basis with profit distributions largely derived from the future growth of the business; the after-tax effects are mitigated by time and cash flow mechanisms.

In other words, a smaller book serves more as the “ticket onto your ship” than an immediate windfall and automatic and full equity position. The process might sound complicated, but we’ve seen it done hundreds and hundreds of times—it works, if you know what you’re doing. The equity position will be immediate, but the equity is usually bought and paid for on an installment basis over time using future growth and profit distributions to make the payments and sometimes the process will need to be augmented with stock grants. Experience dictates that most G-2’s/G-3’s will take this deal and run.

The S corporation entity structure is rigid and inflexible which correlates to a rather predictable result given the limited but straight-forward options available. That can be a very good thing. The LLC model, in contrast, at least when taxed as a partnership can offer some distinct tax advantages and flexibility when faced with these issues, so if onboarding talent is a possibility, the LLC structure is probably the better entity choice. Regardless, the problem is solvable if both sides see the advantages of working together and want to solve the problem. Taxes are always a high hurdle, but almost never an impenetrable wall.

The Case of the Super Producer

If the book is large enough that it becomes a negotiating point, life is about to become more interesting. Not to belabor the issue, but this is exactly why you should stop using revenue-sharing arrangements and building in those fracture lines that you’ll later have to work to overcome and pay to weld back together. It is possible to onboard these larger books, and our success rates seem to be around 50/50, but the process is more complicated in terms of legalities and tax repercussions and ownership-level compensation and the situation can reach a point where it can no longer be recovered or saved. This is the case of the super producer.

There is no magic number to define a “super producer,” but start by thinking about revenue streams upwards of $250,000 (i.e., the amount of money that the producer takes home from their share of the eat-what-you-kill or revenue-sharing compensation system. It is not unusual to see super producers taking home upwards of $500,000 to $1,000,000 per year, and the process becomes more challenging the higher the level of production. Super producers often are very experienced, very confident, and they are well rewarded for focusing on and excelling at really just one thing—making it rain.

Super producers often find themselves in an interesting position. They get paid as much or more than most owners. They control their own work day, they have few of the headaches that owners have (payroll, hiring, firing, training administrative staff members, signing an office lease, executing a line of credit, etc.), and they take on very little risk in terms of building a business and creating or investing in infrastructure. But super producers, as we’re defining the term, are not shareholders. They have no equity stake in the business under whose roof they work. They are often treated like a partner, and often called a partner, but they are not. Super producers don’t get paid last like an equity partner does—they get paid first, right off the top line.

Super producers commonly argue that, while not an equity partner of the overall business, they are indeed an owner—they own “something.” On this point, they’re right. They have control over cash flow and client relationships and that can translate into real value and real equity. Most super producers don’t reach that level of production on their own and without ongoing support, so the question often shifts to “Is the book sustainable if taken to the street?” Interestingly, this tends to remain largely a theoretical issue as the book and its owner aren’t interested in setting up a stand-alone, fully competitive business model, though it may take time for this realization to emerge. At the same time, they’re not typically excited about becoming a minority owner and an at-will employee of a larger business.

The negotiation pattern often includes a certain level of brinksmanship, but more often than not, these models are successfully onboarded one way or another, at one time or another. Super producers have a lot of control over cash flow, with the understanding that they rely on someone else’s infrastructure investment to survive and prosper. Regardless of the bravado and confidence that comes with high levels of production and low levels of risk, super producers have a significant weakness—their cash flow is nearly worthless if they ever stop working, die, or become disabled. G-1 can exert a significant amount of influence over that book and the client relationships that generate the cash flow in G-2’s absence (i.e., in the event of G-2’s death or disability) and as a result, the book is often not saleable or transferable without G-1’s agreement. The older a super producer gets, the clearer this issue becomes. In the end, super producers and the businesses that they are affiliated with are usually better off together than separate and that is what both sides eventually figure out, though with a fair amount of hand-wringing and angst along the way.

The onboarding process typically follows the pattern outlined in the previous section, and again yields to the realities of the entity structure and taxes. The super producer contributes all right, title and interest in his/her book in exchange for a buy-in opportunity that has a few more incentives added in (at least when compared to a smaller book). The major difference is not in how the equity is acquired, but rather in how much equity is acquired—super producers have a first-class ticket onto your ship, not a coach-class ticket.

In the end, even if an equity position for the super producer does not work out, there is a tolerable fallback position. Think back to the life raft and ship parable. It is possible to coexist as two different models. If you and the prospective G-2 candidate can’t get the deal done, it does not mean that the relationship has to end. Cash flow is still a valuable commodity in a growing business, and circumstances might be better years from now to warrant revisiting the issue. In the meantime, allow the life raft (G-2) to tie up alongside your ship (G-1) and enjoy the benefits of the continuing revenue-sharing arrangement. You have the benefits of the advisor/producer’s knowledge, camaraderie, and cash flow; he or she gets to enjoy the benefits and infrastructure of a larger business and the protection it can provide (think continuity arrangement), while earning a good living and retaining 100 percent of his or her own equity value. It can work, and often does.

As in the previous section, being organized as an LLC and taxed as a partnership can provide a lot of flexibility and some important options and tools for solving the case of the super producer.

Help Wanted Ad

If you’re looking for a G-2 or G-3 level advisor, you may well need to mine the talent pool and run a help wanted ad. Businesses require good people who are willing to work hard and make long-term commitments. Finding the right people and subsequently retaining them often starts with the right hiring process.

This is hard work and it is an imperfect process that requires careful decisions and a quick trigger if (maybe when is the better word) you’re wrong. Better to restart the process than labor to make a poor fit seem like a good fit. My G-1 partner, Brad, has a great saying on the hiring process: “When expectations turn into hopes, it’s over.”

From our perspective, the best source of great people is a referral from a trusted source. Still, cast the net wide and interview as many qualified people as you can find. But don’t hire someone and try to find a plan the person fits into; set up a clear, long-range succession plan first and hire the people you will need to achieve your professional and financial goals. In general, as a growing business, hire for a business twice your size and plan accordingly. Hiring without understanding your end-game strategy often turns into a disaster—or worse, in this industry, a group of separate books that turn into competitors.

Consider placing an ad or notice like this in a number of locations, including online sources (don’t forget your own website by including a tab for “Career Opportunities”), your local Financial Planning Association (FPA) chapter, your local AICPA chapter, and with the local colleges, depending on the talent and age level you’re searching for:

Seeking an Experienced Financial Advisor

ABC Financial Services, LLC is an established financial advisory firm serving clientele in the southwestern United States from our main office in Scottsdale, Arizona. We are in the family wealth management business focusing on high net worth individuals, families, and business owners. Through a planning process built on integrity, knowledge, and attention to every last detail, we seek to guide and inform our clients to successfully navigate the various phases of financial and wealth management. We have been serving this area and market niche for over 25 years and we have a constantly evolving succession plan in place to ensure that we’ll be here 50 years from now.

This is a special opportunity unlike most in the financial services industry. First, our firm is completely independent, so our loyalty belongs exclusively to our clients. Second, we offer a competitive compensation structure (salary and a bonus) and an equity ownership track for employees who demonstrate hard work and leadership characteristics and support the long-term goals of our firm. You will be a member of a collaborative and supportive team of strong individuals, all working hard to help us grow a successful and multigenerational business. At ABC Financial, you won’t “own a job” or be building your own practice; this is not an eat-what-you-kill position, and we’re not that kind of a firm.

If you are a financial advisor with [#] or more years of experience and an established client base, we encourage you to contact us and explore an opportunity with our firm. All inquiries will be held in strict confidence. At a minimum, candidates should be able to bring the following assets to the firm:

- [$] assets under management

- [#] years of experience working with high net worth individuals/families and business owners

- Awareness of financial planning issues related to managing wealth

- Bachelor’s degree and Series 65/66 or CFP designation

- Familiarity with portfolio management, including tactical asset allocation, traditional and nontraditional asset classes, and various investing styles is a minimum requirement. We prefer sophisticated estate planning, tax planning, education planning, and insurance planning knowledge, as well as strong knowledge of the stock market and macroeconomic trends

- Attention to detail; strong organizational skills; ability to complete work in a timely, accurate, and thorough manner

- Must be personable and punctual, and a problem solver

- Clean disciplinary record

Advisors who meet the above criteria may inquire confidentially about this opportunity by submitting a cover letter and resume to [HR Manager] at ____________________________.

Solving the Talent Crisis in This Industry

Depending on the publication and the writer, the average age of an independent financial professional or advisor seems to range from 50 to 60 years of age. Based on our past 1,000 completed valuation clients, the average age of an owner is 52. Based on our observations as we stand in front of groups of advisors 100 times a year, there is a lot of gray hair in the audience. Since older often means wiser, that’s not necessarily a bad thing, until older translates into the attrition model because there are no internal, next-generation advisors to take over. The bottom line is that this industry is getting older, and the complaints about lack of next-generation talent are growing louder.

Still, it is our opinion that the aging of the independent financial services industry is but a symptom of a bigger problem. This profession no more has a problem with aging than a reservoir with a bad leak suffers from a lack of new water supplies.

The problem this industry faces is not a lack of new, younger, and qualified advisor talent; it is a lack of talent willing to work their way up a ladder that is nothing more than a mirage. It isn’t that younger, next-generation talent can’t see the opportunities in this industry—it’s just the opposite. They see what’s going on very clearly, and they pass up the opportunity to build a one-generational, valuable practice that is totally dependent on one individual selling products, services, or advice. In some ways, they should be commended for smart thinking and stellar observational skills and running away from this opportunity toward another that is better and more lucrative and rewarding. It is not their job to fix this industry—it is ours.

When younger advisors or prospective financial professionals are successfully recruited into a practice that has no future beyond the career or life of its founder and that founder is in the last 10 years of his or her career, the natural tendency is for new recruits to build their own practices or books; there is no better choice. Said another way, if there is no enduring business to invest in, each next generation of advisors starts to build their own practices and we’re caught in a perpetual loop. Older practices die off and new practices spring up on a continual basis, but using the same assembly tools and compensation methods, the results are equally predictable. That is not an attractive proposition to anyone other than a professional recruiter.

Solving the talent crisis in this industry is well within reach. Think about it. Independent financial practices and businesses provide an excellent living often tied to recurring or predictable revenue, earned at relatively low cost, with the highest equity value of any professional services model. What’s not to like? The short answer is the lack of enduring business models that enable this industry to more rapidly evolve, improve, and recruit the best of the next-generation talent base. This industry should be the leader in planning and building professional service models, and one day, we think it will be.

A Conversation with the Next Generation

I recently had the opportunity to present to a group of students from Texas Tech University about the industry they were about to enter into, what to look for in a future employer, and what to avoid. Before getting into the specifics of my conversation with this group of next generation advisors, it is important to acknowledge the work of people like John Gilliam, PhD, CFP, CLU, ChFC, who is an Associate Professor and Director of the Master’s Programs at Texas Tech University in the Department of Personal Financial Planning. John’s work, and that of many others like him at the university level across this country, is critical to the future of the independent financial services industry and our ability to help advisors build enduring and transferable businesses.

The students we spoke to wanted to know how they could identify a business or a firm that could provide the necessary level of mentoring and one day offer them an ownership opportunity, if they earned it of course. They also wanted to know how they could identify and avoid a practice model that would not survive its founder’s retirement, death, or disability.

Our advice to every G-3 advisor prospect we talk to is this: First, concentrate your search on the independent side of the industry where there is a culture of ownership. The wirehouse side, even the insurance side of this industry as it is currently structured, offers an opportunity to make money and to learn, but zero opportunity to become a shareholder or an owner with a real equity position. Those can be good models to learn your craft in, but they are the wrong models if you aspire to ownership or becoming an entrepreneur in your own right.

Second, understand that you may need to separate the learning opportunity from the ownership opportunity, at least in the early years of your career. We tell you this, G-3, so that you can separate an opportunity to learn and earn an income at an independent practice, from an opportunity to accomplish those goals and participate in an ownership track with a business or a firm. In other words, in some circumstances, it isn’t enough to want to become an owner—many practices are too small to ever offer the opportunity, but that doesn’t mean you can’t benefit from working there. There are tens of thousands of small, independent practices that offer an opportunity to learn and grow in a hands-on environment. Just understand what the long-term prospects are going in.

Third, do not accept a revenue-sharing arrangement (where you receive a percentage of everything you produce) or any form of an eat-what-you-kill compensation structure. Negotiate for a salary and bonus structure. If you’re offered a revenue-sharing arrangement, run. That is an operation that will die in the end anyway; it is just a matter of when. If you are in the position of having to sacrifice an ownership opportunity in an enduring business in order to get a job and make some money, don’t do further damage by taking on the risk of ownership-like production before you’re ready. There are better jobs available.

In terms of how to approach an employer with your desire to become an owner, be honest, and be humble. Tell them that you’ll work hard (and understand that my generation does not consider 8 to 5 to be hard work!), and that you’ll do what is necessary to succeed within the boundaries provided to you (i.e., recognize that this is a highly regulated industry where initiative is appreciated, as long as you don’t go too far), and that you’re willing to invest a career, but would like to have an opportunity to buy-in to the firm; say it that way, or they may think you expect to be compensated with ownership. Gauge their reaction and adjust from there. If they react negatively, or they seem put-off, understand that more than 95 percent of the practice and business owners in this industry are one-owner, one-generational models. You can’t fix that, so in the end, or at some point early in your career, you’re looking for the 4 percent or 5 percent that can offer something more. They’re out there.

Here’s how to find them. In general, you want a firm with at least 60 percent recurring revenue (fees or trails). You need a firm that is an entity (look for an “Inc.” or an “LLC” after their name). You need them to be with an IBD or a custodian. There are more than 4,000 broker-dealers in this country, and you’ll have heard of maybe 50. Focus instead on the leader of the business you want to work for. When the opportunity arises, or through your own due diligence, ask and obtain answers to these simple questions:

- Is this business strong and growing?

- Does your business have a succession plan?

- How many owners does this business currently have?

- Do you anticipate this business having more owners in the future?

The independent financial services industry is an excellent career choice. Make the first step into it a good one.